6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

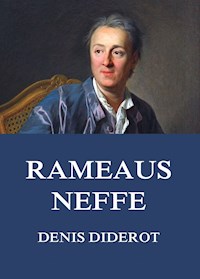

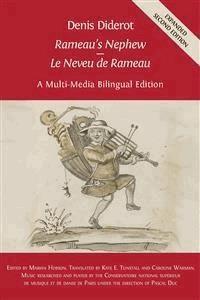

In a famous Parisian chess café, a down-and-out, HIM, accosts a former acquaintance, ME, who has made good, more or less. They talk about chess, about genius, about good and evil, about music, they gossip about the society in which they move, one of extreme inequality, of corruption, of envy, and about the circle of hangers-on in which the down-and-out abides. The down-and-out from time to time is possessed with movements almost like spasms, in which he imitates, he gestures, he rants. And towards half past five, when the warning bell of the Opera sounds, they part, going their separate ways.Probably completed in 1772-73, Denis Diderot’s Rameau’s Nephew fascinated Goethe, Hegel, Engels and Freud in turn, achieving a literary-philosophical status that no other work by Diderot shares. This interactive, multi-media and bilingual edition offers a brand new translation of Diderot’s famous dialogue, and it also gives the reader much more. Portraits and biographies of the numerous individuals mentioned in the text, from minor actresses to senior government officials, enable the reader to see the people Diderot describes, and provide a window onto the complex social and political context that forms the backdrop to the dialogue. Links to musical pieces specially selected by Pascal Duc and performed by students of the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris, illuminate the wider musical context of the work, enlarging it far beyond its now widely understood relation to opéra comique.This new edition includes: - Introduction - Original text - English translation - Embedded audio-files - Explanatory Notes - Interactive Material

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Denis Diderot

Rameau’sNephew—LeNeveudeRameau

Open BookClassics

Denis Diderot

Rameau’s Nephew—Le Neveu de Rameau

A Multi-Media Bilingual Edition

Edited by Marian Hobson

Translated by Kate E. Tunstall and Caroline Warman

Music researched and played by the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris under the direction of Pascal Duc

http://www.openbookpublishers.com

Text © 2016 Marian Hobson, Kate E. Tunstall, Caroline Warman, Pascal Duc

Music © 2016 Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris

The text and the music are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of it providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Marian Hobson, Kate E. Tunstall, Caroline Warman, Pascal Duc, Denis DiderotRameau’s Nephew — Le Neveu de Rameau: A Multi-Media Bilingual Edition. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0098

Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. For information about the rights of the Wikimedia Commons images, please refer to the Wikimedia website (the relevant links are listed in the list of illustrations).

In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254909#copyright

Further details about CC BY licenses are available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

The translation in this book is from Denis Diderot, Satyre Seconde: Le Neveu de Rameau, ed. Marian Hobson (Droz: Geneva, 2013), by kind permission of the publisher.

All external links were active on 14/6/2016 unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781909254909#resources

This is the fourth volume of our Open Book Classics series:

ISSN (Print): 2054-216X

ISSN (Online): 2054-2178

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-90–9

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-91-6

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-92-3

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-93-0

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-94-7

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0098

Cover image: Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin, ‘Qu’importe’ (c.1740–c.1775), in Livre de Caricatures tant bonnes que mauvaises. Watercolour, ink and graphite on paper, 187 x 132. Waddesdon, The Rothschild Collection (The National Trust). Photo: Imaging Services Bodleian Library © The National Trust, Waddesdon Manor, all rights reserved.

All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified.

Printed in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia by Lightning Source for Open Book Publishers.

Contents

List of Musical Pieces

vi

Preface to the Second Editionby Marian Hobson

1

Rameau’s Nephewtranslated by Kate E. Tunstall, Caroline Warman

15

Le Neveu de RameauFrench edition ed. by Georges Monval (Paris: Plon, 1891)

99

Notesby Marian Hobson

179

List of Illustrations

235

Contributors

245

Acknowledgments

247

List of Musical Pieces

The music mentioned by Diderot in Rameau’s Nephew is French and Italian, although Diderot was also well aware of the work of other foreign composers, such as C.P.E. Bach. The pieces specially performed and recorded for this multi-media edition were chosen to provide samples of music or composers that are less well known today, or to give examples of transcription, one of the principal ways that pieces came to be known and played in a private setting at the time.

Throughout this book the musical note symbol identifies when a recording is available. To access these musical pieces either click on the symbol or refer to the relevant endnote. If your device supports MP3 files you will be able to listen to the music directly. Alternatively, you can access the music online by following the links or scanning the QR codes provided.

The musical extracts recorded for this edition are available to download at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783740079#resources. All musical recordings have been released under a CC BY license and their copyright belongs to the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris.

François-André Danican Philidor, L’Art de la modulation[The Art of Modulation], extract:Sixth suite: Sinfonia (Adagio — Allegro ma non troppo)

Clémentine Frémont, traversoJosef Žák, violinTatsuya Hatano, violinRémy Petit, celloFelipe Guerra, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.04

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9057234b/f2.image.r=l’art de la modulation.langEN

180

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Fêtes de Polymnie [The Festivals of Polyhymnia], extract:Air: ‘A la beauté tout cède sur la terre’ [Everything on earth gives way to beauty]

Dania El Zein, sopranoRémy Petit, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.05

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k398018b/f70.image.r=fêtes de polymnie.langEN

188

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Fêtes de Polymnie[The Festivals of Polyhymnia], extract:Air: ‘Au vain plaisir de charmer…’[To the empty pleasure of charming…]

Dania El Zein, sopranoRémy Petit, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.06

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k398018b/f145.image.r=fêtes de polymnie.langEN

188

Jean-Philippe Rameau, Fêtes de Polymnie [The Festivals of Polyhymnia], extract:Air en rondeau: ‘Hélas, est-ce assez pour charmer…’ [Alas, in order to charm, is it enough…]

Dania El Zein, sopranoRémy Petit, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.07

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k398018b/f107.image.r=fêtes de polymnie.langEN

189

Pietro Locatelli, Sonata op. VI no 5, extract:Aria (Vivace)

Tania-Lio Faucon-Cohen, violinSarah Gron-Catil, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.08

Score available at http://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/id/1034692

191

Domenico Alberti, Sonata for the fortepiano op. I no. 5, extract:Andante — Allegro

Luca Montebugnoli, piano (Clarke/Lengerer)

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.09

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9058374h/f15.image.r=alberti.langEN

192

Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Stabat Mater, extract, transcribed for solo violin by Johan Helmich Roman.

Tania-Lio Faucon-Cohen, violin

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.10

Score available at http://conquest.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/e/e5/IMSLP14647-Roman_Stabat_Mater__arr_solo_violin_.pdf

211

Jean-Féry Rebel, Pieces for the violin, divided into suites by keys, extract:First suite in G-sol-ré: Allemande

Josef Žák, violinAntoine Touche, celloLoris Barrucand, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.11

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90099503/f9.image.r=Pièces pour le violon.langEN

213

Jean-Féry Rebel, Pieces for the violin, divided into suites by keys, extract:First suite in G-sol-ré: Prelude

Josef Žák, violinAntoine Touche, celloLoris Barrucand, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.12

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90099503/f7.image.r=Pièces pour le violon.langEN

213

Jean-Joseph Mouret, Les Amours de Ragonde, ou la soirée de village [The Loves of Ragonde, subtitled An Evening in the Village], extract:Bourrées I-II

Clémentine Frémont, traversoNicolay Sheko, oboe

215

Josef Žák, violinTatsuya Hatano, violinFelipe Guerra, harpsichordRémy Petit, cello

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.13

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9058670w/f24.image.r=ragonde.langEN

Jean-Joseph Mouret, Les Amours de Ragonde, ou la soirée de village [The Loves of Ragonde, subtitled An Evening in the Village], extract:Air: ‘Accourez, jeunes garçons’ [Come running, young men]

Marie Soubestre, sopranoSarah Gron-Catil, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.14

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9058670w/f23.image.r=ragonde.langEN

216

Egidio Duni, Le Peintre amoureux de son modèle [The Painter in Love with his Model], extract:Arietta: ‘Dans le badinage, l’Amour se plait’ [Love is pleased with playfulness]

Marie Soubestre, sopranoClémentine Frémont, traversoJosef Žák, violin

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.15

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b9067334z/f64.image.r=le peintre amoureux.langEN

218

Johann Adolf Hasse, Cléofide, extract:Air: ‘Vuoi saper se tu mi piaci?’ [Do you want to know if I like you?]

Fiona McGown, mezzoJosef Žák, violinRémy Petit, celloLouis-Nöel Bestion de Camboulas, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.16

220

Nicola Antonio Porpora, Polyphemus, extract:Act III, sc. 5: Aria: ‘Alto Giove’ [Jove on high]

Victoire Bunel, sopranoTania-Lio Faucon-Cohen, Ajay Ranganathan, altosJuliana Velasco, Marie Bouvard, Josef Žák, Patrick Oliva, Catherine Rose Barrett, Cyril Lacheze, Tatsuya Hatano, violinsSarah Gron-Catil, Rémy Petit, Antoine Touche, cellosBenoît Berrato, bassAlejandro Perezmarin, bassoonTakahisa Aida, harpsichord/organMartin Gester, conductor

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.17

221

Nicola Antonio Porpora, Polyphemus, extract:Act III, sc. 5: Recitativo and Aria: ‘Senti il fato’ [Feel the hand of destiny]

Victoire Bunel, sopranoTania-Lio Faucon-Cohen, Ajay Ranganathan, altosJuliana Velasco, Marie Bouvard, Josef Žák, Patrick Oliva, Catherine Rose Barrett, Cyril Lacheze, Tatsuya Hatano, violinsSarah Gron-Catil, Rémy Petit, Antoine Touche, cellosBenoît Berrato, bassAlejandro Perezmarin, bassoonTakahisa Aida, harpsichord/organMartin Gester, conductor

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.18

222

Leonardo Vinci, Twelve solos for a German flute or violin with a thorough bass for the harpsichord or cello, extract: Sonata II: Sicilienne and Allegro

Clémentine Frémont, traversoFelipe Guerra, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.19

225

Leonardo Vinci, Elpidia, extract:Air: ‘Barbara, mi schernisci’ [Cruel woman, you scorn me]

Fiona McGown, mezzoTatsuya Hatano, violin

226

Rémy Petit, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.20

Score available at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b90675797/f10.image.r=elpidia.langEN

Pietro Locatelli, Six sonatas for three parts, two violins, or two flutes, and bass with a harpsichord, extract:Sonata op. V no. 2: 1st Movement: Largo-Andante

Tania-Lio Faucon-Cohen, violinClémentine Frémont, traversoSarah Gron-Catil, celloCamille Ravot, harpsichord

Recording available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.21

Score available at http://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/id/1004479

228

Fig. 1 The ‘real’ Rameau’s Nephew? Reproduction of a drawing by J.G. Wille, at present not traced. The reproduction was first published by G. Isambert in his edition of Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau, with notices, notes and bibliography (Paris: A. Quantin, 1883).

Preface to the Second Edition

© Marian Hobson et al., CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0098.01

In a famous Parisian chess café, a down-and-out, HIM, accosts a former acquaintance, ME, who has made good, more or less. They talk about chess, about genius, about good and evil, about music, they gossip about the society in which they move, one of extreme inequality, of corruption, of envy, and about the circle of hangers-on in which the down-and-out abides. The down-and-out from time to time is possessed with movements almost like spasms, in which he imitates, he gestures, he rants. And towards half past five, when the warning bell of the Opera sounds, they part, going their separate ways. This is the plot of Rameau’s Nephew.

Why present another translation of such a well-known work?

Translations need to adapt the work being translated to the language into which it is being put; so much is obvious. Less so is that language creates a context that changes constantly, sometimes at great speed. There is a need for renewal in the reception of a work in translation. A new Rameau’s Nephew, we felt, was called for.

Why an interactive, online, Open Access edition?

Such an edition opens possibilities not available to earlier translations — techniques move on, as well as languages. An interactive, online edition is particularly suited to Diderot, who wrote mostly in dialogue, though sometimes the dialogue was asymmetric (as in Rameau’s Nephew, between HIM and ME). In fact, he loved talking. As if in conversation, his writings change their relation to the reader constantly, forcing her to laugh, to argue, to wonder. He usually doesn’t write in discursive form but in fragmentary, often teasing fashion. He would like an audience, clearly, he tacks around to force one into being and into action — but he is dead, he is words on a page (and dust in the Church of Saint Roch, Paris). We may come closer to discussing with him through an interactive edition than in any other way.

Diderot and the Web

‘Diderot’ is a site under construction. The energetic, the brilliant, the sometimes overbearing, sometimes timid man, or what remains of him, lies unpantheonized somewhere in the Église Saint Roch, in the rue Saint Honoré. An atheist, his friends had to find a sympathetic priest who would allow church burial, and then, gravely ill, he had been moved to the rue de Richelieu to die, so as to be within the parish, his bones were then disturbed in a search for lead from coffins, to make bullets, during the Revolution. Likewise, his manuscripts lie even now lacking a definitive edition (how unlike his friend/enemy Rousseau). Yet in an online memorial1 ‘amorifera’, the bearer of love, saying she shares his birthday, October 5th, gaily invites Diderot to dance — he himself had said he was never very good at dancing, much as he would have liked to dance well (one can imagine him repeating this even as he accepts the invitation across death and dust).2 And he would surely have been convulsed with laughter at one of the adverts funding this memorial site, lady ‘singles’ seeking partners.

By telescoping time, we can imagine that he would have published his great Encyclopédie online.3 Not merely for the geographical reach it makes possible, much as this would have enthused him: this translator from the English, this critic of colonialism, this satirist of tax manipulators and banking activities, this anxious consciousness of where authoritarian government might lead, would have welcomed no doubt the fluidity and the ability to disappear from notice that the web provides, however imperfectly. Yet, once more, not merely: he wanted what he wrote to produce change. His mind was mobile, but his principles were not, or not too much. He might dodge and duck and dive to get out of prison or to help a friend who had insulted some great ladies (thereby hurting perhaps even endangering, others);4 the atheism, the materialism that are the load bearers of his writings did not change: less Church, less intolerance, more toleration of other sexualities, other nations, other opinions. Above all, he sought more freedom to speculate. In his great writing, this surfaces mostly in quizzical, satirical or paradoxical works, often in dialogue. First among which is Rameau’s Nephew. Would he, Denis Diderot, have published this work online had it been possible?

Well: he didn’t publish it in any form, but rather seems to have left it in manuscript and probably in the care of others, several others, without clear instructions that we know of as to what destiny he designed for it. This may have been hesitation, or perhaps mobility of intention — he liked to ‘wind others up’ like clocks, as English slang so forcefully says, yet he was fearful of giving pain. And if it seems from his autograph manuscript (though less from other copies of the text)5 that he deliberately arranged the beginning and the end of his Rameau’s Nephew in terms of precise place and time, one can wonder whether the naming of names that marks out this satire doesn’t also include a kind of reserving of final meaning, a speculative swinging, so that the reader cannot always be sure exactly what the aim is. One example: our no. 76 — a note only possible since 2012 and Colin Jones’ fine work on the Saint-Aubin manuscript held at the National Trust, Waddesdon Manor, UK,6 where appears the magnificent caricature of the naked Deschamps, a famous actress and prostitute, being escorted from the house of a tax-collector, Villemorien. This may fill in detail for the reader who wonders why the very next satirized name to be mentioned, in apparently unrelated way, is precisely that of Villemorien.7 So the cultural effect of the web is to accelerate; in the case of an edition, it quickly coordinates items which might otherwise have taken years to connect. A further example: in a chess match played blindfold in London in April 1793 by the great chess-player, composer, and acquaintance of Diderot, Philidor, the pieces, so a contemporary London newspaper tells us, were placed by a nephew of Rameau.8 This can hardly be our Nephew, dead in great poverty in 1777, but presumably another of the numerous progeny of Rameau the composer’s brother. The anecdote allows the surmise that there were connections maintained between the two families which very likely went beyond the mere possibility that Philidor and this Rameau both happened to be keeping a safe distance from Paris during the Revolution.

There is, then, a great deal more that might be found out about the people alluded to in the satire, and why Diderot picks them out. The digital resources associated with this edition are therefore also a site under construction, open to addition and correction. And to speculation. For there exists a kind of connection between Rameau the Nephew and Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, a faint link, but present. A self-description of Rousseau, only known by a passage in a Rousseau manuscript unpublished in his lifetime is actually quoted about Rameau the Nephew: ‘Nothing is more unlike the man than he is himself’ (‘rien ne dissemble plus de lui que lui-même’). This passage, describing HIM, appears here at the very beginning of the dialogue. It had, however, already been used by Rousseau to describe himself in Le Persifleur [The Debunker], a manuscript newspaper which he and Diderot briefly worked on in the late 1740s, and which wouldn’t be published until 1781.9 Indeed, some of the discussion between ME and HIM might seem like shadowy versions of the debates between those two ‘enemy brothers’, in Jean Fabre’s fine phrase, which we may imagine to have taken place in the period of their close friendship, the 1740s. And it is hard to imagine Diderot writing about Rameau, uncle or nephew, without having Jean-Jacques in mind, he whose bad relations with the great composer had been one cause of trouble to the Encyclopédie as an undertaking.

Music in Rameau’s Nephew

That Diderot admired Rameau’s music is clear, even when through the mouth of the Nephew he sends up some of the formulaic quality of its component parts in music or in libretto. It has been recognized at least since the crucial work of Daniel Heartz,10 how important music is in Diderot’s dialogue. But since then, Diderot criticism has tended to see the dialogue as enacting the cusp of an important change in eighteenth-century music, from Rameau to the ‘nouveaux chants’ as ME and the Nephew call the music of the opera comiqueand of its associated composers. The music embedded in our edition offers a development of this, for the selection deliberately shows how much Diderot also refers to music which is not that of the opera comique, and which moreover is not likely to be at all familiar to non-specialist modern readers, even those who are lovers of eighteenth-century music: Hasse, Porpora, and a composer whose name Diderot added in the margin, Traetta, for instance. Our publication, with embedded music, has thus hinted that a rebalancing of ideas about the musical background to the text may be needed.

Much of this music is not well known to a general readership, as we have said. But beyond this, it is not always exactly clear from the text which piece of music HIM or ME are referring to. In introducing music into our edition, we hope that gradually through future work it may become clearer whether Diderot refers in every case to precise pieces or passages of music. A better grasp of this dilemma would throw light on the much more general question of how allusively (or not) Diderot writes, a question whose importance the first part of this preface began to suggest. We have offered suggestions about the music, which can now be discussed and endorsed or corrected.

We could have been content with references to online excerpts. To have done so would have meant to rely on excerpts not always or by any means of the best quality.11 But the most important innovation for readers is more adventurous: to introduce music, specially recorded for this interactive book, which is embedded in the digital editions and can also be listened to on smart-phones or online. This obviated major problems that we would otherwise have faced: that of the cost of rights, if music recorded on DVD had been used; that of hiring an orchestra, which would have involved huge expense, quite beyond our research budget so generously provided by a grant from the Leverhulme Trust. Even so, our examples are often necessarily limited to excerpts, not whole pieces. Our solution, only possible through the kind cooperation of the Conservatoire national de musique et de danse de Paris, is dual: the pieces specially selected, performed and recorded for this multi-media book were chosen, as our first edition indicated, ‘to provide samples of music or composers that are less well known today’, or ‘to give examples of transcription, one of the principal ways that pieces came to be known and played in a private setting at the time’,12 for music circulated in the eighteenth century as much by transcription and private performance as by public performance and publication. Pascal Duc directed its performance by students of the Department of Early Music. For this collaborative work, of translation, edition, performance and commentary, we (PD, MH, KT, CW) renew here the expression of our great gratitude to all the students involved, whether in performance or in recording and in postproduction techniques, as to all the staff of the Conservatoire who supported the project.

On some editions of Le Neveu de Rameau

In this second edition, in addition to the English translation, we have posted a French version, the one Kate E. Tunstall and Caroline Warman translated. It is that presented in the Droz edition (see note 4 above) and is based on the transcription of Diderot’s autograph published by Georges Monval in 1891, but collated against the editions by Jean Fabre and by Henri Coulet,13 and against a microfilm supplied by the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, who hold the autograph manuscript. We have also posted, in ‘Additional Resources’ (at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/9781909254909#resources) Goethe’s translation into German, 1805, which was the first printed published text of the work in any language. Goethe translated from a copy that has disappeared. The first authentic version in French was published by Diderot’s daughter in 1823, with the publisher Brière, as volume XXI of Œuvres inédites de Diderot. Neither the Brière version nor what can be surmised from Goethe’s translation of the original French it used, was that of the autograph from which they differ in slight but interesting ways. For instance, there is one passage in the Goethe version which is not in the autograph and which yet appears in Brière (1823, p. 31); there is a note in the great nineteenth-century edition of Diderot’s complete works, by Jules Assézat and Maurice Tourneux (vol. V, p. 408 no. 1) saying that the same passage was in the copy they were using. It is a kind of metacommentary, not attributed to the speaker in the dialogue ME, but to an Editor. In Goethe’s version it runs:

‘Hier findet sich im Manuskript eine Lücke. Die Szene ist verändert und die Sprechenden sind in eins der Häuser bei dem Palais Royal gegangen’.

[‘Here there is a gap in the manuscript. The scene has changed, and the speakers have gone into one of the houses near the Palais Royal’.]14

This passage is lacking in the autograph manuscript.15 Fabre in his introduction describes this as clearly an intervention in the margin of folio 42 of Tourneux’ copy, brought back from Russia, which he attributes to ‘an early reader making up by his activity for his lack of intelligence’ (‘un lecteur précoce aussi zélé que peu intelligent’, Fabre, p. xix). There are other jumps in the text which might have attracted a similar comment from Fabre’s ‘early reader’, but have not. The first publisher of the text of Diderot’s autograph manuscript (1891), Georges Monval, pointed this out in a note. He quoted the first more or less authentic text, Brière, here:

Nota de l’édition Brière (1823): ‘There is here a lacuna in the manuscript and we must suppose that the speakers have gone into the café, where there was a clavichord’.

[‘Il y a dans le manuscrit une lacune, et on doit supposer que les interlocuteurs sont entrés dans le café où il y avait un clavecin’.]

And continued firmly (we are in 1891):

‘The autograph original shows that there is no lacuna: the speakers have not gone out of the café, where there is no clavichord’.

[‘l’original autographe montre qu’il n’y a aucune lacune: les interlocuteurs ne sont pas sortis du café, où il n’y a pas de clavecin’.]

Coulet, in his edition of the text,16 which is at present by far the most complete as a critical edition, has suggested that this marginal edition comes from alterations made in other copies (those in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, Vandeul I) which suppress mention of the café la Régence in which the conversation is taking place, because, as Monval and before him, Asselineau, had pointed out, the ‘correctors’ haven’t understood that the harpsichord on which the Nephew plays is imaginary.17

However, following a suggestion from the musicologist David Charlton,18 it seems possible that we have with this problem an almost effaced sign of a slightly different version. He relates this to ‘pp. 77-78 […] where the text apparently refers to an earlier version of the scene, imagined taking place outdoors in the street instead of the café interior, when ‘the neighbours came to their windows’. Charlton believes that the later part of the dialogue, in particular the passages round the nature of song, may incorporate patches of developments out of Diderot’s earlier dialogue, Entretiens sur le ‘Fils naturel’, published in 1757.

Our interactive edition

So we must recognize the still incomplete state of our knowledge about the actual way in which Diderot developed his dialogue. Rameau’s Nephew, is entitled ‘Satyre seconde’ and nothing else on the title page of the autograph manuscript. The spelling reminds us of the licentious mythical beast, the goat-man; the work itself has some very funny dirty stories. Yet it is a satire in a different sense, it is stuffed with personal allusions, it names and shames a whole roll of minor actresses and big stars, Grub Street inhabitants, dodgy newspapers and especially the then version of bankers, the ‘farmers’ of taxes or of offices. It takes them off, it takes them down, several or every peg they ever climbed. This kind of edition makes it much easier to understand who these people are, why Diderot may be getting at them. At a click, the reader can cause their portrait and their biography to appear.

The click is worth making — the similarity to our post-financial crisis world is hard to miss: bankers, celebrities, paparazzi, rise from the pages, with little sense of shame and often little talent, except for pushing themselves ahead. The dialogue’s very lack of conclusion, where the talkers just separate at the sound of the opera bell announcing the performance, leaves us looking at what may be coming towards us, in somewhat shaky or indistinct fashion. The instability of attitude, the changes of scale and weight in what HIM and ME talk of, makes me wonder about what is only a couple of decades down the time-line: 1789, and ask whether its shadow is perceptible in Diderot’s dialogue.

Likewise, Diderot seems to foretell a transformation outside politics, one of sensibility, of our relation to our own feeling for music. We hope to have made an understanding of this possible in this edition — the digital form has enabled us to embed into the text pieces of music specially selected and directed by Pascal Duc. This engenders, we hope, an awareness of the musical context of the dialogue, enlarging it well beyond its relation to opera comique.

This bringing forward of Neapolitan comic opera, with its often physical comedy, connects implicitly with Diderot’s dazzling descriptions of the Nephew’s pantomimes. The foolery performed with musical instruments by the great Swiss clown, Grock (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JUgPO2VF-k, one of many clips), and the telling movements of the great violinist Gidon Kremer when playing (for an extreme and breathtaking version, performed with others and developed into dance, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UAM2y1SOsIs) are both inheritors of the tradition into which Diderot places his dialogue: the near-dancing, the use of the body as an instrument. But the clowning, the spilling-over of expression moves with Rameau the nephew from the active and the liberating into almost painful movements, into bows and scrapes which are as if extorted. He is, but he is also made to be.

So gesture and pantomime as well as utterances explore the self-awareness of HIM, his consciousness of his lack of freedom, subject as a musician both to his instrument and to his audience. HIM has exploited this lack of freedom — he bows, he scrapes with artistic flair. By perfecting his flattery through self-consciousness, by not being identical to what he is made to be by his patrons, he has contrived to turn his very servitude into a kind of liberty, a liberty raised to the second power, arrived at through an awareness of his bonds. His ironic exploitation of his own turpitude brings it to the level of an art. The strange form of the dialogue reinforces this, for it allows a sideways take on what is said, a striking but puzzling contrast between an objectivized persona, HIM, and first person experience — the narrative by ME. The form, a dialogue not as face to face but as if skewed, seems to have been invented by Diderot and it is puzzling that, to my knowledge, this form is only found in German authors who actually met Diderot or who were interested in him: Lessing, Wieland, Herder, F.H. Jacobi.

Indeed, the first interest in Rameau’s Nephew came from Germany. It was Goethe who at the promptings of Schiller engineered in 1805 its first appearance on the stage of ‘world literature’ — to use a term first coined by the great German poet himself. It was thus not in French but in Goethe’s German translation that the work was first read. One of the reasons why Goethe produced the term ‘Weltliteratur’ was to escape the divisions of the Napoleonic wars and to seal the claims of his national literature to an attention equal to that accorded to classical French literature or the works of Shakespeare. It is for this reason that we have posted Goethe’s translation in the additional resources available at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/9781909254909#resources, Weltliteratur fits the work of Diderot like a glove, if only by the roster of major thinkers who have commented on it: Hegel, Engels, Freud, Bernard Williams.

Each found there a link to his own work. To take the closest to Diderot in time: Hegel probably had personal reasons to draw attention to Rameau’s Nephew in his Phenomenology (1807), for earlier he had asked Goethe for help in obtaining a post. But there are intellectual reasons also. With exemplary insight, through careful quotation, he picks out two main threads in Diderot’s dialogue: first, the question of ‘species’, espèce, translated, for the most part, in the present version as specimen. One of the philosophical problems that Hegel embeds in the very structure of his major work is the ‘besondere’, the particular. As he moves through the experience of humanity, like a weaver’s shuttle between the universal and the singular, all and one, summarizing and linking, he picks out what lies between them, the particular, what can form a ‘species’, what catches different possible groupings of experience, of moments of thought. And Diderot throughout this work plays with lists, with different ways of collecting together actions and professions and characteristics. The second area on which Hegel insists is music. What appears to interest him most is the way in which Diderot has, through music, sketched out a kind of movement of history, whereby consciousness and hence sensibility make each moment unique, differentiated from the past by what has been in our past. Our ears carry our experience, and we cannot have innocent ears, or innocent experience either. Having listened to the music of the Italian comic opera, Diderot suggests through the mouth of HIM, we cannot go back unchanged and listen to the French composers, to Rameau, as before.

There is another attraction for Hegel. The ‘hero’ of Rameau’s Nephew twists and turns in his argument, moving from assertion to negation and back through negation to assertion. Hegel places his discussion of Diderot’s work in the moment before the great cataclysm that was the French Revolution, in an historical space where complex historical forces vie against each other, acting and reacting against each other. Jean Starobinski, examining in detail the texture of Diderot’s writing has pointed out the use of a rhetorical form which is not one of true Hegelian dialectic (where we might move from a thesis which is negated to a new thesis developed from negating the negation) but is that of chiasmus. In this figure of rhetoric, a position negated leads us back to the starting point; we do not move on, but stay as it were blocked by a contradiction.19 Yet Diderot ends his dialogue by letting it swing into an open future, one of generality and indistinctness conveyed by the proverbial saying — ‘he who laughs last laughs longest’, says HIM.

How then does Diderot structure his dialogue, if it is left wide open? He makes the beginning and end definite in time and place: as said, it begins after lunch, at the café de la Régence; it comes to a stop shortly before five-thirty, when the opera is about to commence — it was close by. Diderot, then, seems to place different sections of the composition, one after the other, with no discernible linear order. Indeed, one wonders if some sections do not recur as variations on a theme. For example, Voltaire’s play, Mahomet, occurs twice in relation to Voltaire’s public actions, one criticized — his writing In Praise of Maupéou, the other praised — his rehabilitation of the judicially murdered Protestant, Jean Calas. The reader in fact wanders and wonders. We move through a hailstorm of allusions, a multitude of moods. We hope that the appreciation of this strange work, the route we take as we read, will be made clearer and livelier by this new translation, and the resources of music and images it brings with it.

What these comments on editions, including our own, show is how little what Diderot was up to was understood by his very early readers and perhaps by his modern ones. The line between studying different editions of a Diderot text and following his game-play may be very hard, even impossible to draw. In the case discussed above at p. 7, Jean Fabre, to whom so much is owed, pointed out how the commentary from a puzzled editor was very early incorporated into the flow of Diderot’s text. One can understand why this might have been done if one thinks of his novel Jacques le fataliste, where exactly this sort of remark is part of the game played by the writing, and which Schiller and Goethe so much admired.20

List of French editions consulted

J.L.J. Brière, Œuvres inédites de Diderot: le Neveu de Rameau Le Voyage en Hollande, à Paris, MDCCCXXI [in fact, 1823].

Charles Asselineau, ed. Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau (Paris, 1862).

Jules Assézat and Maurice_Tourneux, Œuvres complètes de Diderot, vol. V, Le Neveu de Rameau (Paris, 1875).

Georges Monval, Diderot: le Neveu de Rameau, Satyre publiée pour la première fois sur le manuscrit original […] (Paris, 1891).

Jean Fabre, Diderot: le Neveu de Rameau, édition critique avec notes et lexique, (Genève: Droz, 1950).

Henri Coulet, Le Neveu de Rameau, vol. XII, Œuvres completes de Denis Diderot (édition DPV), ed. H. Dieckmann, J. Proust, J. Varloot, vol. XII (Paris: Hermann, 1989).

Denis Diderot, Contes et romans, Édition publiée sous la direction de Michel Delon avec la collaboration de Jean-Christophe Abramovici, Henri Lafon et Stéphane Pujol (Paris: Gallimard — Collection Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, no. 25, 2014).

Michel Delon, Denis Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau, Édition de Michel Delon Collection Folio classique (no. 4464) (Paris: Gallimard, 2006).

Denis Diderot, Satyre Seconde: Le Neveu de Rameau, ed. Marian Hobson (Droz: Geneva, 2013).

1 See http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=6239031

2 See the great love poem in which the body-molecules of lovers mix after death, part of a letter to his lover Sophie Volland, 15th 0ctober 1759, written ‘au Grandval’, that is, from the country house of the materialist philosopher, the Baron d’Holbach, in Diderot, Lettres à Sophie Volland, édition présentée et annotée par Marc Buffat et Odile Richard-Pauchet (Paris: Non Lieu, 2010), Non Lieu, collection ‘lettres ouvertes’, pp. 77–79: ‘if it were given to us to make up a being in common; if in the sequence of centuries I were again to make a whole with you; if your dissolved lover’s molecules were to start to shake, to move around and to seek for yours, scattered abroad in nature…’ (grateful thanks to Odile R-P for this reference; translation MH).

3 As has been done now, from Chicago, Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., eds. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project (Spring 2016 edition), ed. by Robert Morrissey and Glenn Roe, http://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu/.

4 See M. Hobson’s French edition, Denis Diderot, Seconde Satyre: le Neveu de Rameau (Geneva: Droz, 2013), pp. 205–13.

5 See the end of this Preface, and also material round the posting of Goethe’s translation, at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/9781909254909#resources

6 Colin Jones, ‘French Crossings IV: Vagaries of Passion and Power in Enlightenment Paris’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 23 (December 2013): 3–35. A truly wonderful story, a scatological companion to Rameau the Nephew’s account of Bertin and Mlle Hus having sex.

7 Yet another example of how the web can change our view of Diderot’s writing, if as do many still, we see it as lacking connection and hopping from subject to subject.

8 Sporting Magazine, 2(1) (April 1793): 8, ‘Chess Club at Mr. Parsloe’s St. James’s street, Sporting Magazine,3(5) (February 1794): 282; Paul Metzner, who found this reference, believed it to refer to our Rameau’s nephew, which is not possible, as he had been dead nearly twenty years (see Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1968)).

9 There is no other evidence that Diderot knew the remark, seemingly made about himself by Rousseau. See M. Hobson, ‘From Diderot to Rousseau via Rameau’ [‘Diderot et Rousseau par Rameau interposé’], in Diderot and Rousseau: Networks of Enlightenment, ed. and trans. by Kate E. Tunstall and Caroline Warman (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 2011), pp. 15–29.

10 Daniel Heartz, Music in European Capitals: The Galant Style 1720–1780 (New York and London: WW. Norton & Co., 2003); Heartz, From Garrick to Gluck: Essays on Opera in the Age of Enlightenment, ed. John Rice (New York: Pendragon Press, 2004), Opera series no. 1.

11 Our notes nonetheless supply links for the interested reader.

12 M. Hobson (ed.), Denis Diderot’s ‘Rameau’s Nephew’: A Multi-Media Edition, translated by K.E. Tunstall and C. Warman. Music researched and played by the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris under the direction of P. Duc (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2014), p. xix, http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044

13 Jean Fabre, edition of Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau (Geneva: Droz, 1950); Henri Coulet, Le Neveu de Rameau, vol. XII, Œuvres completes de Denis Diderot (édition DPV), ed. H. Dieckmann, J. Proust, J. Varloot (Paris: Hermann, 1975–).

14 ‘Denis Diderot’s Rameaus Neffe’, with notes by Joanna Raisbeck, additional online resource available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/shopimages/resources/2.Rameaus-Neffe.pdf, p. 12.

15 See p. 23 of the translation into English by Tunstall and Warman (Open Book Publishers, 2014), p. 39; edition by Hobson (Droz, 2013), p. 25; edition by Fabre (Droz, 1950).

16 Diderot, Le Neveu de Rameau,ed. Henri Coulet (Paris: Hermann, 1989), p. 96 (vol. XII of DPV).

17 Le Neveu de Rameau, ed. Charles Asselineau (Paris: Poulet-Malassis, 1862).

18 Kindly made in private communication.

19 Jean Starobinski, ‘L’emploi du chiasme dans le Neveu de Rameau’ [‘The use of the figure of the chiasme in Le Neveu de Rameau’], Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 89(2) (1984): 182–96.

20 We list here some modern writings which seem to us to endorse the vividness and power of Diderot’s dialogue, without necessarily mentioning it: Jérôme David, Spectres de Goethe: les métamorphoses de la ‘littérature mondiale [Ghosts of Goethe, Metamorphoses of World Literature] (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, coll. ‘Les prairies ordinaires’, 2012), a dialogue for the most part between LUI and MOI [HIM and ME]. Stéphane Audeguy, Fils unique [Only Son] (Paris: Gallimard, 2010) — an ‘autobiography’ of Rousseau’s elder brother (who disappeared without trace in Rousseau’s childhood). Thomas Bernhard, Wittgenstein’s Nephew, translated Ewald Osers (London: Quartet Books, 1986) [original German, 1983]. Saul Bellow, Dangling Man (New York: Vanguard Press, 1944).

Fig. 2a Portrait of Denis Diderot (1766), by Jean-Baptiste Greuze.

Rameau’s Nephew

© Marian Hobson et al., CC BY http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0044.02

Second Satyre1

Vertumnis, quotquot sunt, natus iniquis[‘Vertumnus scowled on his birth, and made him a versatile failure’]

Horace, Book II, 7th Satire.2