11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

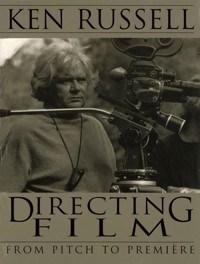

In this ground-breaking book, acclaimed film director Ken Russell unpacks the creative insights, technique, know-how and sheer determination that have enabled him to realise on screen more than fifty diverse and yet intensely personal films. Drawing on his parallel experiences of producing, screenwriting and editing - as well as his favourite (and some unfavoured) movies by other directors - Russell places the role of the director as auteur within the context of film-making as a collaborative enterprise. As a bonus, Russell offers critical insights into his vision and intentions in several of his own movies, including an exclusive focus on his most recent film.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 151

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

DIRECTINGFILM

DIRECTINGFILM

FROM PITCH TO PREMIÈRE

KEN RUSSELL

CONTENTS

1 Pitch

2 Treatment to Screen Play

3 Casting

4 Pre-production

5 Principal Photography

6 Post Production

7 Premiere

8 Back to the Future

9 Ken Russell Filmography

Index

CHAPTER I

THE PITCH

Everyone who has ever tried to get a film made is a con artist. OK, so sue me! Alright, I’ll amend that: everyone who has tried to set up a movie is a liar and a cheat, or at best, a big fat fibber. And that’s kosher because everyone in the industry knows that and not only makes allowances, but actually condones it. The one exception is me – in my early days, or to be honest, on my very first day. The date was January 3, 1959, with three amateur movies behind me, three children under three and at the ripe old age of 33, I was pitching for my very life – a chance to become the greatest director the world has ever known or remain a mediocre photo journalist who was the laughing stock of Fleet Street.

The editor of the photo magazine I freelanced for, had sent me to Spain to get some material on Alexander the Great, starring Richard Burton, which was shooting out of Madrid. He’d also arranged a free trip on SwissAir, providing I took a few publicity stills for them on the way out, with permission to shoot anywhere on the plane. For reasons now forgotten, I flew from Paris Orly at the crack of dawn. Where to start? I loaded my camera and looked around. And there it was – a paparazzi’s dream come true.

Now what would that be today … Princess Di as an angel flown down from heaven to give him an exclusive? Or perhaps Charles caught in flagrante in the back of a Land Rover with Camilla Parker Bowles. Yes, it was that big. Well, I’m no paparazzi anyway, but it was a very big opportunity to become one, or even start a trend, for I don’t think the breed even existed back in 1954. Yes, I had a scoop, an exclusive – there wasn’t another photographer around for 39,000 feet.

OK, OK, I’m coming to it. The hottest scoop in the world at that minute was sitting in Row D, seats 1 and 2 – the window and the aisle. They had just secretly married and were on the first day of their secret, secret honeymoon, to a secret, secret destination nobody in the whole, wide world knew about except me. News had got out that very morning that they had just got hitched in Paris and then vanished. It was the hottest story in town, every town – it was the romance of the decade, the love story on everyone’s lips, a fairy tale come true … wait for it – the marriage of Audrey Hepburn to Mel Ferrar!

Ancient history now, but years ago an earth-shattering event. Trembling and full of trepidation I raised the camera to my eye and focused … on the ecstatic lovers with stars in their eyes. I had never seen a happier couple until they caught sight of me. The stars clouded over, I was about to invade their private world and turn their summer into bleak midwinter. I lowered my camera and without as much as glancing in their direction, shamefully returned to my seat.

We arrived in Madrid and I had barely stepped into the glare of the Spanish sun, where there was still not a photographer in sight, before I heard my name being called on the PA system. It was a phone call – the editor. He was beside himself with delight.

‘Get the film to the pilot. He’s doing a quick turn around and flying straight back to Heathrow. We’ll have it in tomorrow’s first edition – world exclusive.’ My reply was a verbal suicide note to my career in photojournalism.

Everything now hinged on my interview at the BBC Television Studios at Lime Grove with Huw Wheldon, who in the late 1950s was the editor of the world’s first regular TV arts magazine, Monitor. Now was my big chance to make a fresh start with a career I’d always set my heart on ever since the age of nine, when I opened my one and only Christmas present to find a toy projector and a film of Felix the Cat.

“…age of nine, when I opened my one and only Christmas present to find a toy projector and a film of Felix the Cat.”

Monitor had only been running a year. John Schlesinger, the resident documentary filmmaker, was about to leave to make his first feature film. A replacement was needed and Wheldon, who had seen one of my amateur movies and liked it, had granted me an interview. If I could pitch an idea for his programme that appealed to him, I’d be home and dry. His first quip, ‘Bit long in the tooth to start a career in film, eh?’, hadn’t exactly put me at my ease, neither had his hawk-like appearance with beetling brows, beak of a nose and thrusting jaw. ‘You’ve seen our programme, I presume, and know our style, so what do you propose?’ he said.

(Overleaf) Still from ‘Elgar’, the BBC drama documentary that started the great Elgar revival. The still shows Elgar riding the Malvern Hills as a boy.

‘A film on Albert Schweitzer playing Bach to lepers in the jungle,’ I stammered.

And of all the pitches I have delivered since, and there have been many, none have been more certain of rejection. The hawk glowering at me from behind his massive desk metamorphosed into a thundercloud about to strike me a fatal bolt of lightning. But a split second before it could do so, I started talking – fast.

‘Of course, what I’d like to do most of all is make a film on the poet laureate, John Betjeman, reading his London poems in situ.’ The storms clouds lifted.

“‘A film on Albert Schweitzer playing Bach to Jepers in the jungle,’ I stammered.”

Visions of a film unit flying to darkest Africa, hiring native bearers, trekking through impenetrable jungle to film a doctor with a heavy German accent, playing boring old Bach to an audience who didn’t even have the means to applaud, was not then, in 1959, the stuff to win friends and influence viewing figures. And I suspect the same would hold good for today. Just imagine the budget! Whereas dear old John Betjeman was as cuddly as a teddy bear, spoke perfect English – though not too posh – and could be filmed outside his very own door in Smithfield meat market. No air transport, no native bearers and no big budget.

‘If you can shoot it in three days, with a crew of three, for 300, you’re on,’ said the Man of Power, now looking as pleased as punch. Seems three’s my lucky number. And as things transpired, I continued to pitch ideas to Huw Wheldon at Monitor for many years to come with consummate success. In fact, I can only remember him rejecting one idea in twenty over the next five years. During that time, the boot was often on the other foot – as feature film producers started pitching at me.

Such a one was Harry Saltzman; producer of the Bond films, The Battle of Britain, and the Harry Palmer trilogy. He wanted me to make the third and last Harry Palmer. Not because of my succession of acclaimed drama documentary films, such as ‘Elgar’, ‘Prokofiev’, ‘Bartok’ and ‘Debussy’ – nd for once the journalist hadnnone of which he’d seen. But because Mike Caine, who played Palmer, had seen them and convinced him that my imaginative style of filmmaking would bring a fresh look to the series.

Harry Saltzman, no longer with us, alas, was a grey ball of cosmic energy. Grey suit, grey hair and round as a … well, er, ball.

‘I understand you make art films,’ he said at our first meeting. ‘I like art, my house is full of it. And I’d like to make an art film with you. Anything special you have in mind?’

‘Well I’ve always wanted to make a film on Nijinsky,’ I said.

‘Not a bad idea,’ he said, ‘there hasn’t been a film with a race horse as the star since National Velvet – could be a big money-spinner.’

‘Sorry, Mr Saltzman,’ I said, ‘I didn’t mean the Derby winner, I meant the dancer.’

Russell showing ‘Elgar’, the drama documentary, to the makers of the Monitor TV programme, (left to right) Alan Tyrer (film editor), Ken Russell, Huw Wheldon, Peter Cantor (assistant editor).

‘No film on a dancer ever made money,’ he snapped back.

‘Then how about Tchaikovsky?’ I ventured.

‘Tchaikovsky’s fine,’ he said. ‘In the meantime, if you wanna break into features you’ve gotta start off with a sure thing. The Ipcress File and Funeral in Berlin were big box office bonanzas and Billion Dollar Brain’s gonna be the biggest yet. Get that one under your belt, get yourself a name and then we’ll talk Tchaikovsky. Your first feature film is all important.’

‘But I’ve already made a feature film, Mr Saltzman,’ I foolishly ventured, ‘French Dressing.’

‘That doesn’t count;’ he retorted, ‘they tell me it was shot in black and white.’

And so he talked me into it.

Some time later when I reminded him of his promise he was deeply offended that I’d had the effrontery to bring it up. Billion Dollar Brain was not the box office hit Harry had hoped for, so he was less than happy when I reminded him of his promise to let me make a film on Tchaikovsky, but as it happened he had a marvellous ‘out’. ‘Too late,’ he said triumphantly. ‘Dimitri Tiomkin’s gonna make one for the Soviets and he’s already writing the music.’

Huw Wheldon and Peter Cantor of the Monitor TV programme with Ken Russell, working on the ‘Debussy’ drama documentary at BBC Elstree studios.

Well, I did get to make that film on Tchaikovsky, but Harry didn’t produce it, United Artists did. They had financed and distributed Billion Dollar Brain, and talked me into directing Women in Love. Although the Harry Palmer movie had only made a respectable financial return, the D.H. Lawrence movie went through the roof, so understandably, they were going to look with a friendly eye on any other movie I might propose. But at the mention of the word Tchaikovsky, their faces fell. ‘What’s it about?’ they asked mournfully.

‘It’s about a homosexual who falls in love with a nymphomaniac,’ I said. Without another word they gave me the money. It was the most successful pitch of my life.

Of course, luck has a lot to do with it as does belief in guardian angels and tooth fairies, and, believe it or not, even the gentlemen of the press. Or gentleman to be more precise, because the favours I have received from them as a body can be counted on the fingers of one foot. And as is often the case, the gentleman’s headline was untrue:

Russell and Huw Wheldon discussing ‘Isadora Duncan’ at the Elstree studios.

‘Twiggy to star in Ken Russell’s The Boy Friend.bout a homosexual who fall’ And for once the journalist hadn’t lied – I had.

Not to say I hadn’t dreamed that headline often enough. Twiggy was an icon of the sixties, along with the Beatles and a bevy of present day old age pensioners of the same ilk. She was the most photographed fashion model of the decade and certainly the most popular – cockney accent ‘n all. Twiggy was everywhere and wherever there was Twiggy there was Justin de Villeneuve, playing Professor Higgins to her Eliza Doolittle. Or perhaps Svengali to her Trilby would be closer to the truth. To the world he was her best friend and manager. They were a great couple and completely inseparable, speeding between fashion shoots in a posh Porsche by day and living in Arabian Night’s splendour by night – encouraging me to sample a little of both.

“‘It’s about a homosexual who falls in love with a nymphomaniac,’ I said. Without another word they gave me the money.”

Another thing we shared was a passion for Sandy Wilson’s pastiche musical ‘The Boy Friend’, which paid homage to the bright young things of the roaring twenties with their doo-wack-a-doo high-stepping lifestyle, which at the time was enjoying something of a revival. Twiggy and I were both huge fans of the show and were discussing it over a glass of champagne at the Ritz one day, when we both became conscious of a lurking journalist wishing he had an ear trumpet. The occasion was the launch of a new Justin de Villeneuve superstar, in the form of a highbrow opera singer about to graduate to a career of lowbrow pop. But the nosey guttersnipe (members of the gutter press never cease sniping at me) was more interested in what we were saying than the operatic pop coming over the PA system.

‘Thinking of putting Twiggy in one of your films, Ken,’ he said without ceremony.’

“E already ’as,’ chirped Twiggy, ‘me and Justin woz shootin’ down at Pinewood only larst week workin’ on The Devils.’

The guttersnipe was gobsmacked. ‘Not with all those naked nuns?’ he said, sensing he had missed the scoop of the century.

‘Yeah,’ said Twiggy, ‘we woz a couple of King Louis’ courtiers in the ‘Rape of Christ’ scene in the cathedral. I was dressed as a boy and Justin woz in eight-inch ’igh ’eels with cupid bow lips and a blonde wig.’

Deflated, the guttersnipe sank down to join us on the settee as he hid his disappointment over the loss of a golden photo-scoop. But true to type, soon bounced back again. ‘Didn’t I hear you mention ‘The Boy Friend’?’

‘My next project,’ I lied, ‘… and guess who’s starring in it?’

‘Not …?’ said the guttersnipe, first gawping at Twiggy, who modestly dropped her head, then looking back to me for confirmation. I merely smiled, but that was enough to send him scuttling off to make his call. ‘Cor, you ’aint ’arf gawn an’ dunnit now, Ken,’ said Twiggy.

Twenty-four hours later I was on the carpet in the office of the President of M.G.M. England, as he brandished the newspaper with the aforementioned headline.

‘Are you responsible for this?’ he asked grimly.

‘Well yes, and no,’ I said truthfully. What was coming next? A demand for me to make a humiliating public denial or what? Much to my delight it was the, ‘or what?’.

‘Do you think you can pull it off?’ he said. ‘We’ve owned the property for years and never knew how to handle it?’

I improvised my pitch on the spot. ‘It’s a great little stage show, but as it stands it would never transfer to the big screen and we have to think big … like Busby Berkeley who made all those big blockbuster movies in the 30s … make it a sort of homage to M.G.M.’s Gold Diggers of 1933, Broadway Melody and 42nd Street.’

‘What’s the storyline?’ said the President.

‘Well,’ I said, my mind racing and mindful of the 42nd Street plot. ‘Er, well, there’s this little theatrical company touring in the stix. And there’s a kid in the show; she’s only the A.S.M., but she’s a real talent and all she needs is a good break …’

‘Twiggy?’ said the President.

‘Yes, Twiggy!’

‘Can she dance?’

‘By the time I’ve finished with her she’ll be another Ginger Rogers.’

And who’s your Astaire?’

‘Tommy Tune, great Broadway talent, all 6’ 6’ of him.’

‘And how does Twiggy get her break?’

‘She gets it … er, when the star of the show breaks her leg.’

‘And who plays the star; you’ll need a real name or it won’t work.’

My mind raced; the recent Minister of Transport came to mind … ‘Er, Glenda Jackson.’

‘We couldn’t afford her.’

‘For me, she’ll do it for love.’

The President’s mind raced. ‘Go on,’ he said, only half convinced.

‘And, of course, Twiggy’s the hit of the show.’

‘Is that it?’

‘No, that’s only half of it.’

‘Tell me the other half. Where do the big Busby Berkeley production numbers come in?’

‘In the mind of this Hollywood director who comes to see the show. He’s thinking of turning it into a lavish Panavision movie.’

‘They didn’t have Panavision in those days.’

‘They didn’t have stereophonic sound either, but we’ll have both. Anyway, he imagines how he’d stage the numbers and that’s when we dissolve from the small stage to the super-spectacular.’

Vladek Sheybal as the Hollywood director de Thrill on the lookout for talent in The Boy Friend.

‘How about the human interest?’

‘Well, apart from the usual sub-plots, De Thrill, the Producer, wants to take Twiggy to Hollywood to star in the movie.’

‘That’s what you’d expect.’

‘But she won’t go. She gives up stardom in Hollywood because she’s fallen in love with a boy in the show and wants to stay with him in England.’

‘That’s all.’

‘Er no, De Thrill and his long lost son are reunited.’

‘His son?’

‘The Tommy Tune character.’

‘How does he recognize this son?’

‘By the double bunny hop and the Delaware drag.’

‘By the double bunny hop and the Delaware drag?’

‘That’s a dance step his Dad taught him when he was a kid.’

‘How’d they get separated?’

‘In the 1917 Revolution – they got separated in St. Petersburg when they were touring Russia …’

And so it went on, with me making it up as I went along. And believe it or not, they gave me the money to make the movie. And I’d guessed right; Glenda Jackson did do it for love – and a canteen of silver-plated cutlery.

By and large you’ve got to give the moneymen something to hang their hopes on. Once I guaranteed some investors that I could make Oscar Wilde’s Salome for under a million dollars. Think that’s a lot of money? Think of Titanic and think again.

Selling the idea of Bram Stoker’s last story, ‘The Lair of the White Worm’, was a doddle – he wrote Dracula in case you have forgotten.

A vampire film inspired by the master of the genre, with snake fangs instead of bat teeth just has to be worth a gamble, especially when a semi-naked Amanda Donohoe is doing the biting and sucking, and dishy Catherine Oxenberg is sacrificed in Marks & Spencer’s underwear to a giant virgin-eating phallus.

Then there’s the ploy of financing a potential new hit on the back of an old hit.

D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love made money, so The Rainbow