Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

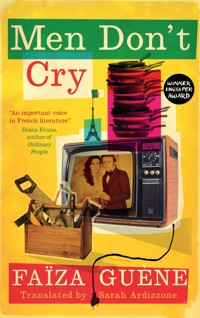

Yamina Taleb is approaching her seventieth birthday. These days, she strives for a quiet life, grateful to the country that hosts her and her adored family. The closest she gets to drama is scooping 'revolutionary' bargains in the form of plastic kitchenware gadgets. But Yamina's children feel differently about life in Paris. They don't always fit in, and it hurts. Omar wonders whether it's too late to change course as he watches the world pass him by from the driver's seat of his Uber. His sisters are tired of having to prove themselves and their allegiance to a place that is at once home, and not. When the Talebs go away together on holiday – not to the motherland, but to a villa-with-pool rental near the Atlantic coast – they come to realise just how strongly family defines our sense of belonging. Moving between Algeria and Paris, Discretion touchingly evokes the realities of a first- and second-generation family as they carve out a future for themselves in France, finding one another as they go along. Winner of the Prix Maryse Condé 2020 Best Summer Books of 2022 - Fiction in Translation-- Financial Times 'Wonderful. A vivid, soulful novel. Guène's Paris is a place of grifting and grafting where young rebels rub up against calcified traditions. This is a writer at the height of her powers, addressing issues of migration and belonging with defiance, zest and humour.'--Bidisha 'Faiza Guene is an important voice in French literature, rebelliously dissecting ideas of home, identity and belonging with a universally accessible intimacy and power.'--Diana Evans 'One of the hottest literary talents of multicultural Europe.'--Sunday Telegraph 'Through the lens of an often-tender family portrait, the author delivers a biting portrayal of a France steeped in hypocrisy and false smiles, where equality of opportunity is all smoke and mirrors … A novel that's bang on the money, coursing with a chillingly legitimate sense of grievance.'--Slate 'Like every accomplished novel, La Discrétion does so much more than tell a story. It asks questions ... Faïza Guène's mastery of her subject matter means she doesn't come down on either side but accompanies her characters towards the light.'-- Le Monde Diplomatique

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 218

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DISCRETION

Faïza Guène

Discretion

Translated from French by Sarah Ardizzone

SAQI

Saqi Books

26 Westbourne Grove

London W2 5RH

www.saqibooks.com

Published 2022 by Saqi Books

First published in French as La discrétion by Éditions Plon in 2020.

Copyright © Éditions Plon, un département de Place des Éditeurs 2020

Translation © Sarah Ardizzone 2022

All rights reserved.

Faïza Guène has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designsand Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

Frantz Fanon extract on p. 115 © Translated by Constance Farrington.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 86356 402 4

eISBN 978 0 86356 447 5

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

This book is supported by the Institut français (Royaume-Uni) as part of the Burgess programme, and by the Institut français’s ‘Programme d’aide à la publication’.

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PEN’s ‘PEN Translates!’ programme, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers’ freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly co-operation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

To my motherTo all our mothers

It demands great spiritual resilience not to hate the hater whose foot is on your neck, and an even greater miracle of perception and charity not to teach your child to hate.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

COMMUNE OF AUBERVILLIERSDEPARTMENT OF SEINE-SAINT-DENIS (93300)FRANCE, 2018

Yamina is coming up for seventy. She will reach this age in November of next year. On either the tenth or the nineteenth of the month. Yamina was born one day or the other.

According to her Algerian documents, it was the nineteenth, but her French residence permit, issued in Seine-Saint-Denis, states: ‘Born 10 November 1949 at Msirda Fouaga, Algeria’.

Who to trust?

At least she has been spared a presumed birthdate, the notorious 1 January, assigned, by default, to colonised subjects.

Passengers are quick to offer Yamina their seat on the 173 bus, which she catches every Saturday morning from Fort d’Aubervilliers métro station, opposite the post office.

She is off to the Mairie d’Aubervilliers market to make all sorts of pointless purchases. Plastic tat and ‘revolutionary’ kitchen gadgets mainly, peddled by hawkers in headsets up on their platforms. Yamina could watch these shows for hours, enthralled. She sometimes claps in wonder at the end of a demo, even if the result is far from convincing – her trusting nature means she has no sense of being hoodwinked. Such an idea would never occur to her.

She wants to believe in the miracle demonstrated with fervour by the trader with the gift of the gab. It comes easily: no arm twisting is needed. She’s ready to take this cheery Von Dutch-cap-wearing traveller at his word, despite the speed of his patter as he extols the magic of the all-purpose peeler.

The self-appointed preacher of Aubervilliers market always uses the same opening gambit on the shoppers gathered before his stand: ‘M’sieurs, dames, bonjour! My name is Moses, and I’m God’s right-hand comrade-in-arms!’ Broad-chested and short-legged, the street vendor stands rooted to the spot. His fingers never brush the hands of the women he showers with small change, his hairy forearm flaunting a home-made tattoo: Pour toi, Suzie.

Yamina sets off again, convinced she’s scooped a gadget and bagged the deal of the century.

The Mairie d’Aubervilliers market is an important ritual for Yamina. She heads there on her own, enjoying chance encounters with some of her girlfriends, avoiding others. Especially the journalists, which is her nickname for those who ask too many questions: ‘What about your daughters? Still no marriage prospects?’ Polite to a fault, Yamina defers to destiny: ‘God will decide.’

Yamina hurries to catch the 173 in the opposite direction, the family ritual of Saturday lunch on her mind. The flourish with which she flashes her freedom pass – the driver giving her Navigo Forfait Amethyste card a cursory glance through tinted lenses – owes a debt to the detectives in her favourite TV series.

When people offer to give up their seat for her, she refuses at first: ‘Non merci, it’s kind of you, but I’m fine,’ indicating she’s capable of standing upright in the middle of the bus, wedged between two pushchairs. As if her balance won’t be in jeopardy, as if the bend in rue Danielle Casanova won’t swing her about. Not that she takes umbrage at being offered a seat on the basis of her age, not at all, she appreciates politeness. She just doesn’t want to cause any bother. You have to make a point of insisting before she’ll say yes. It’s the same with the youths smoking cheap hash at the foot of her building, when they offer to carry her shopping upstairs: ‘I’ll be fine, my children, I can cope.’

They understand not to take no for an answer, they’re used to her, and still they have to wrestle the bags out of her hands. She gives in with a smile but thanks them all the way to the threshold. She is touched by their help, remarking before she closes the door: ‘You’re good boys!’

The prospect of growing old does not frighten Yamina. She made her peace with it years ago, and appears unaffected by the tribulations of old age.

Yamina never complains.

It is as if that option was excised at birth.

And yet she is not without health problems, and must remember to take her pills twice a day to control her diabetes and blood pressure. Every couple of months, she visits the Lamarque laboratory on rue Helène Cochennec to run her blood tests. She takes the results to the doctor who’s been her GP since 2003. The surgery is located in an old-fashioned house, at the end of a cul-de-sac. There are no appointments, you drop in and wait, sometimes for hours. Magazines with titles such as Challenges or Management are strewn on the dusty coffee table, along with an old copy of L’Express. On the cover, a scrawled-over portrait of former prime minister Manuel Valls, his eyes aggressively scratched out and a moustache added in biro.

Management and Challenges? Who wants to read business magazines in this neighbourhood? Nobody here identifies as the target audience. More’s the pity, given one headline: ‘Making it in France: you can do it and here’s how!’

Best case scenario: someone stands up, scans the coffee table and sits back down again, disappointed.

In the consulting room, the doctor does the minimum, offering little beyond a routine examination.

What’s striking is that when he speaks to Yamina he addresses her informally as tu, not because they’re in any way close, or because he’s an especially friendly doctor. No, he adopts this casual tone after calling her Madame Yamina. For example: ‘Now, now, Madame Yamina, have we been taking our little pills?’ Or: ‘The diabetes isn’t looking tiptop today, Madame Yamina. Have we been putting too much sugar in our mint tea?’

Absurd as it may seem, Yamina is fond of him. Force of habit, probably. She’s been coming here for fifteen years. She keeps the faith. The idea of deserting her GP has never crossed her mind. Her eagerness to ask after the doctor’s own health borders on the comical.

She is, in all likelihood, the only one of his patients to enquire how he is doing, or to press for news of his family, and she does so with unsettling sincerity.

She detects nothing patronising in his tone. Not even when, under the guise of humour, he requests that she bare her ears, which are covered by her headscarf, so he can inspect them with his otoscope: ‘Come on, let’s take off our little burka, shall we, to show our little ears?’

Yamina sees no harm in this. It almost makes her smile.

Nor does Yamina see what these clumsy gestures betray. She doesn’t register that the doctor is brusque and cursory. Sometimes, he knocks her when he lifts her arm to take her blood pressure, but she would never dare point this out. As if being hurt were acceptable. As if nothing really matters, where she is concerned.

Viewed from one angle, Yamina has been preserved. She hasn’t grasped the geometry in which the world has placed her. Her innocence protects her from the violence behind the doctor’s attitude. She doesn’t notice the vertical relationship playing out in the surgery of someone she holds in high esteem, on account of his title, his years of study and his knowledge. She doesn’t see the invisible ladder on which he perches every time he speaks to her.

Which begs the question of whether this is deliberate on Yamina’s part, for she seems unfeasibly deaf to the call of anger. Perhaps she has chosen not to be destroyed by the scorn of others? Perhaps Yamina realised, long ago, that if she reacted to each and every provocation there would be no end to the matter?

Yamina’s father was a resistance fighter. Over there, in Algeria. What if, today, for this woman approaching seventy, refusing to give in to resentment were, in itself, a form of resistance?

Except that anger, even when buried, doesn’t disappear. Anger is passed on, without anyone realising it.

Her children have no time for such treatment. They can’t bear their mother being spoken to as if she were totally gaga and naturally inferior.

They know who she is, and what she’s lived through, and they demand that the whole world know this too.

Take the scene Hannah made the other day at the prefecture.

The official began by talking loudly and slowly from behind the glass partition, over-articulating her words for Yamina’s benefit, as if scolding a child. Something about a missing document. Prompting Hannah, the most sensitive of Yamina’s offspring, to retort: ‘She’s not an idiot. You don’t need to talk to her like that.’

And so, protected by her screen, by the notice reminding the public that action will be taken against any threatening or abusive behaviour, protected by her status as a local government worker, protected by the fact that nobody wants to come back the following day to rejoin this wretched queue, the official doesn’t deign to look Hannah in the eye.

‘Hel-lo,’ she sighs in exasperation, ‘let’s keep a lid on it, shall we? You people are always the same!’

This is all it takes to light the spark in Hannah. To make her feel the sulphur fizzing through her body. Weirdly, she can recall the relevant chemistry lesson: An element with the symbol S. It belongs to the chalcogens and is insoluble.

Hannah wants to cry. Each time someone patronises her mother, it is as if Yamina shrinks before her eyes, like a garment washed at high temperature.

Hannah senses the bile rising, at imminent risk of spilling over. There is so much anger inside her throat that it leaves a bitter taste of ancient anger, increasingly hard to contain. But crying means showing weakness, and that’s out of the question. She is done with weakness.

‘Who d’you think you’re talking to?’

Hannah bangs on the screen while Yamina tries in desperation to restrain her.

‘Binti, my daughter, it doesn’t matter. Calm down.’

The woman behind the counter huffs and puffs again, producing a gob of saliva which sticks to the screen. She, for one, can’t see what the problem is. It’s always the same with these people. They’re never happy! Hasn’t she, a public servant, gone above and beyond her job description – to be understood, to be generous? What have I done wrong this time? Good grief, there’s no knowing what they want!

It’s almost lunchtime and the official is hungry. Fabienne’s stomach is making embarrassing gurgling noises. She’s been out of sorts ever since she started on this high-protein diet, despite her high hopes a few weeks earlier when she bought Dr Jean-Michel Cohen’s book, Lose Weight Healthily, from the Leclerc hypermarket by Normandie Niemen tramway.

She’s trying to patch things up with Bruno, drop some weight, make herself more attractive for him, the way she was before. But Fabienne hardly thrives on deprivation, it makes her feel permanently tense.

For a while now, on top of counting the calories, she has been battling doubt. What if there’s another woman? You think it only happens to other people. ‘Stop getting ideas into your head, Fabienne,’ he says, never looking up from his mobile phone. At first, she tried banishing these negative thoughts. But they’ve rapidly became a fixture: Why’s he started squirting the aftershave bottle fifty-three times when he always used to say perfume was for poofters?

The thing about men is they lose interest, as she has frequently heard her mother remark, so she has been warned. They’ll soon have been married for twenty-seven years. Long gone are the days of feeling a special glow every time his gaze rested on her. Back then, she believed in everlasting love and all that guff about true emotions.

Turns out Bruno is no different, just your average male. The spit of Mr Average.

Every couple they know is breaking into a thousand pieces. Half her girlfriends are divorced. So why should Fabienne be spared? She feels as if she’s competing in On the Posts – one of those endgame challenges in Survivor – clinging on for dear life to avoid falling into the water. The prospect of being single again at fifty haunts her. To make matters worse, if it comes to it, she doesn’t have a single flattering photo to post on a dating website.

Now, more than ever, Fabienne feels overlooked and fragile.

She had been so proud of becoming a local government worker. What a joke! She’s paid for her years at the ‘Pref’ twice, maybe three times over. Just the sight of these dreary walls, the revolting building where she drags herself every morning, makes her feel sick. Scratch Prefecture, this is a tomb. What suicide-inducing architect drew up these monstrous plans? Fabienne has lost count of how many Combo Meal Deals she’s gobbled at the McDonalds in Bobigny 2 shopping centre. Or her reluctant returns after lunchbreaks spent stirring a disgusting café crème at Segafredo, the café on the first floor of the shopping centre where scrawny illshaven men, nearly all of them North African, huddle.

The TV presenter Nagui, with his Egyptian-Italian good looks, is the only Arab to win her approval. He’s not without charm is her take on him, twinkly eyes, not bad. But those guys at Segafredo, they are the sort to make their wives do things. Fabienne pictures those women being made to do it, even on nights when they don’t want to. Of course, they’re knackered most of the time anyway, because of their kids.

Fabienne would put money on the men in the mall being wife-forcers, yes, that’s it, an army of forcers. It makes her feel ill at ease. She doesn’t dare glance at them, still less put her white arms on the café counter. We’ll soon have to pay for our coffee in dinars around here.

She heads back to her desk with a dose of the blues, the kind that clings to the skin. It’s not for nothing Bobigny town centre is a terminus. Everything stops here. You want to be done with it all.

Fabienne has had it up to here with this parade of races and dialects, of smashed-up faces and domestic stories that she’d rather not hear about. She is ill-equipped to deal with the paradoxes of these people: the gazes that smoulder while their hands beg, submissive shoulders belying clenched fists. Too much to understand, too many knots to unravel, plus that’s not her job. They’re behind a blurry screen, so why can’t clients be blurry too? Fabienne is meant to ensure that procedures are followed. Not to take it on the jaw without flinching. Fuck’s sake!

She jabs her finger at Hannah: ‘Hey, you! Calm down, okay!’

The plump pink finger has inadvertently pressed an imaginary button, the red nuclear option.

‘Nah, I won’t calm down! Don’t tell me to calm down! You’ll speak to her with respect, you get me?’

Hannah is nitroglycerine, to be handled with care. Yamina understands this. She knows her daughter inside out. But Fabienne, with no prior knowledge, only makes matters worse.

‘I’d like to remind you that you are speaking to a representative of the State!’

This is all it takes to ignite Hannah. She is ablaze now. Flaring up to defend her mother’s honour.

‘You think I give a damn you’re an agent of the State? You think you’re impressing anyone here? Like, who gives a shit!’

Once again, she bangs on the screen with the full length of her forearm.

‘Fuck you, you fat bitch!’

The blind on the screen snaps shut. Fabienne goes off to lunch, wondering whether to call in sick, leaving Hannah in flames.

Security guards escort the pair off the premises. The mother hand-on-cheek from the shame of it, the daughter on the verge of exploding in the middle of Bobigny prefecture.

One of the guards, with his hi-vis orange armband, makes a show of sympathy. He addresses Yamina as Tata, Auntie, while steering her towards the exit. He’s from the home country: you can tell by his accent. The respect he shows is comforting. But useless. He has no power.

His respect won’t stop the day after from happening. Hannah will have to pay to park a second time before she and her mother cross the concourse and queue for hours. It might be just their luck to end up at Window C, meaning Fabienne’s.

It isn’t until she is sitting in her old blue Renault Clio, diesel, 2006, which she trawled for among the free classifieds and second-hand bargains on Leboncoin.fr, that Hannah notices her knees trembling. She reminds her mother to fasten her seatbelt since Yamina has a habit of ignoring her own safety.

Hannah catches her breath again. Her nerves are strained.

At least she didn’t cry.

All Yamina can give her children is love.

Perhaps her love will soothe them.

With a little luck, it will make them forget the humiliations and unburden them of the sacrifices.

It is still mild for October. The window is wide open and the curtain dances in the breeze. Yamina is grateful to be reuniting her family around the table for Saturday lunch.

In the kitchen, the pressure cooker is hissing deliciously: there’s nothing in the world to beat it. The aroma wafts through the apartment. Yamina has prepared lamb with green beans: a dish her children adore, especially Omar. If happiness had a scent, it would be lamb on the simmer.

Her husband has dozed off on the living room banquette, in front of the television. It’s a rerun of an old western from 1966: El Dorado with John Wayne and Robert Mitchum. Westerns are his favourites. Carefully, Yamina extricates the remote and tucks the cushion behind his neck.

Brahim Taleb is as handsome as ever, his skin remains radiant, his wrinkles like mysteries to be solved. He’s no snorer. Yamina maintains he sleeps like the devout dead, which, coming from her, is high praise.

Standing in the middle of her traditional living room, she notes with pride that there’s not a speck of dust showing on the ornaments, not a crease in the tablecloth. Now it’s just a matter of waiting for her children so she can serve up. The table is already laid.

Yamina leans out of the fourth-floor window, her slim figure and stiff body discernible through her blue gandoura. She watches with affection the kids playing dodgeball outside. It seems only yesterday that her own children were playing beneath this window, without a care in the world, and she would call out their names to summon them back up to the apartment before darkness fell. Yamina sighs. She misses her kids.

It might not strike you at first, but behind Yamina there is a story and there is history, as for each and every one of us.

DOUAR OF ATOCHENEPROVINCE OF MSIRDA FOUAGAALGERIA, 1949

This story begins somewhere in the west of Algeria.

At first glance, you might mistake it for an abandoned nomadic village or douar. Clucking red hens wander past the mournful gaze of a mule tethered to a fig tree.

There are barley fields all around, but the sky has shown no clemency this year, despite the inhabitants’ fervent prayers for rain.

The traditional small stone house, known as a mechta, is bounded by Barbary figs, while the ridges and slopes across the region are dotted with cactus plants.

A heaviness in the air ties stomachs in knots. The last famine wasn’t so long ago, and people still remember it. Everything seems precarious again. Perhaps there’s a sense of foreboding about the ravages of a war to come, like the menace of an overcast sky.

Except there’s no rain. There is still no rain.

Rising up, in the middle of the douar, is a house made of tlakht: this is the clay taken from the mountainside, then mixed with barley bran to build walls. Inside, scant furniture, esparto grass matting on the beaten earth floor and bustling women.

Beads of sweat form beneath their coloured scarves. One of them chants, her voice clear and calm, and, if it weren’t for the brown marks on her hands, it would be impossible to guess at her age. She remains unflustered. You need at least one. This village qabla, the official midwife, offers a reassuring presence, stroking the hand of Rahma, the pink-faced girl, to whom nothing has been explained.

As the pain distorts Rahma’s vision, making her hallucinate, the Berber tattoos on the forehead of the crouching midwife begin to blur. Rahma frowns and stares at the limewashed walls, where she thinks she can see hundreds of lizards climbing in two columns. They look like the French soldiers she spotted catching frogs on the opposite bank of the oued, the river. Apparently, they eat frogs.

She had felt terrified, that day, picking up her pace, her breath quickening with her step. The soldiers exchanged banter, sniggering as they pointed at her taut, swollen belly. One of them whistled and signalled for her to approach. Rahma called on Allah for help as best she could, not being familiar with the correct turns of phrase. Unlike her brothers, she hadn’t been given the opportunity of attending Quranic school.

Rahma’s face hardened as she walked towards the soldiers. She had learned not to show her fear, to be guarded about it. They had taken their land, but they would not take their dignity. She was losing her air of candour, and in its place was a solemn mask, one she would wear forever.

After a brief silence, the soldier jostled Rahma, jabbering in a language she didn’t understand, and the bundle of clothes she was carrying on her head tipped over, tumbling at his feet. A glimmer of compassion crept into his eye: he was on the verge of picking up the clothes, then thought better of it. To hell with her. Let her sort out her own bloody mess. It wasn’t like he’d done it on purpose. Just shoved her about a bit, nothing to write home about.

Algeria, these natives, the other officers’ horror stories… what were they to him? Nineteen months already. He couldn’t wait to return to Brignoles, never wanted to hear talk of Algeria again. Ever since the call-up, his life had been a nightmare. Antoine’s only wish was to take over his father’s garage and repair bodywork. He loved salvaging old jalopies and giving them a second flush of youth. Now that the towelheads, the bicots, had started rebelling, boys like him were being sent to Algeria, when, like everyone else, he’d never asked for it. Antoine was a softie, not given to intimidating women. He wanted to make his friends laugh, end of. This is one shit-dull country – this bled – right? What a godforsaken land.

And laugh they did when they saw the knocked-up bougnoule struggling to bend over and retrieve her laundry – why take pity on a wog? Later, when he turned in for the night, Antoine thought back to the incident, recalling the look in the woman’s shadowy eyes, and felt ashamed of his actions. Naturally, he kept his remorse to himself.

Nothing is more personal than regret.

Rahma had spent much of the day washing and drying the clothes in the sun, on the banks of the oued. Now, because of the frog-eaters, her laundry was dirty again, so she would have to return the following morning to start over.

This girl with plump pink cheeks is still of an age for playing. Something from Rahma’s childhood clings to her as she plunges her bare white feet into the river, hopping and laughing, having first checked the other women aren’t looking her way. She doesn’t want them noticing how much she enjoys walking over the pebbles and watching the clear water pass between her toes. Rahma senses the cool freshness rising to the crown of her head, and it feels delicious.

And yet her childhood is over.

They made a woman of her abruptly.

Perhaps it’s the same for women the world over.

Becoming a woman is sudden, from one moment to the next.