Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

When the Trinidadian novelist, Harold Sonny Ladoo was found dead soon after the publication of his classic novel, No Pain Like This Body, for Christopher Laird, it became an obsession to try to discover the writer behind the work and what had brought about his untimely end. Equal to Mystery – words written by Ladoo – is the record of that pursuit. When, as the editor of a Trinidadian literary journal in the radical years of the early 1970s, Christopher Laird was sent Harold Sonny Ladoo's novel, No Pain Like This Body (1973) to review, he knew he was looking at something revolutionary in Caribbean fiction. It is a novel that has recently been republished as a Penguin Modern Classic. But the next news Laird heard of Ladoo was that he had returned to Trinidad from Canada and had been found dead – very probably murdered – in the canefields outside his family's village of McBean. Laird follows in the path of Ladoo to Canada, where he went to make a name for himself as a writer, and tracks him as a student and young married man through conversations with his widow and other family members. He looks in detail at his relationships with two Canadian writers, Dennis Lee and Peter Such, who supported his work, and in Lee's case published him. Here there is an acute account of their meetings across the line of race, of the mix of generous contact and elusive flight in their relationship. Above all, with access to Ladoo's unpublished material -- short stories and fragments of the vast body of fiction he announced he was writing -- Laird offers acute analysis of what is there, honest bafflement about just what Ladoo was up to, with a tragic sense of the talent that was lost through his untimely death.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 449

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my wife, Alison and three stalwart sons, Kamu, Kaimare and Kazakao. To the Ladoo family and the villagers of McBean. To the incredible dedication and devotion of Dennis Lee, Peter Such and all those who helped ensure that Harold’s Caribbean talent, audacity, and spirit could not be quenched by the vicious events of the night of 16 August 1973 on the silent roads of Central Trinidad.

CONTENTS

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1: Growing Up in McBean

Chapter 2: Leaving McBean, Imagining Tola

Chapter 3: Toronto, Magnificent Captivity

Chapter 4: Two From the Hood

Chapter 5: An Historic Encounter

Chapter 6: Harold at University

Chapter 7: Write What You Know

Chapter 8: No Pain Like This Body

Chapter 9: The Photograph

Chapter 10: Yesterdays

Chapter 11: The Grand Plan

Chapter 12: Stories Inside Stories

Chapter 13: Who Was Harold Sonny Ladoo?

Chapter 14: A Kind of Sensitivity

Chapter 15: The Intruders

Chapter 16: Knight in Shining Armour & Vultures

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Appendices

1. Dennis Lee’s letter responding to Ladoo’s submission

2. Dennis Lee’s first editing letter

3. Dennis Lee’s second editing letter

4. Harold Ladoo’s letter to Austin C. Clarke

5. Manuscripts and typescripts rescued by Jeoffrey Ladoo

6. Victor Questel’s review of No Pain Like This Body in Kairi

7. Christopher Laird’s review of Yesterdays in Kairi

8. Contact sheet for cover photograph taken by Graeme Gibson

9. Ethnic make-up of the Trinidadian population in 1960

Index

INTRODUCTION

FIERCE RECKONING

Only by dying brutally can man become equal to mystery.

— “A Short Story”, Harold Sonny Ladoo, 1973

I never met Harold Ladoo. I discovered his writing almost by accident; it was in 1974, in Port of Spain, and I was working on a soon-to-be-launched periodical called KAIRI.1 One morning a book landed on my desk for review – and to this day I have no idea how it got there, or who sent it. But from the first, staccato paragraph, I was hooked.

Pa came home. He didn’t talk to Ma. He came home just like a snake.

Quiet.

What followed was so spare, so violent, so human that I can still feel the shockwaves it produced. The book was No Pain Like This Body (1972), Harold Sonny Ladoo’s first novel. It exploded in our midst, and set me on a quest that has lasted for nearly fifty years.

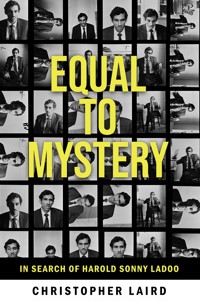

Who was this man, glowering from the back cover of the book with such coiled intensity? The biographical note gave only the skimpiest clues; it said Ladoo was born in Trinidad in 1945, and emigrated to Canada in 1968. Given his surname and the author photo, he was clearly of Indian descent – like half the people in Trinidad. Then in 1974, when his second novel Yesterdays appeared, there was a new biographical detail on the back cover: Ladoo had been killed, in Trinidad, in 1973. He was 28.

Harold Sonny Ladoo: cover photo by Graeme Gibson.

How could such a meteoric talent be snuffed out just like that? And what did it mean for the larger cultural awakening we were exploring at KAIRI? Neither question had an answer, of course. But to even consider the second question, some background is necessary.

Trinidad won its independence from Great Britain in 1962, and for a few years a patriotic optimism prevailed on the island. But the slogans rang increasingly hollow – especially among the young, who were “still waiting for Independence to happen.”2 Much of our land and industry remained foreign-owned, and colonial racial discrimination was still entrenched – overwhelmingly favouring whites, though they made up less than 2% of the population. Meanwhile, a drop in oil prices had depleted the economy, and unemployment was rising. And in the spring of 1970, with streets constantly jammed by thousands of young people protesting, the army mutinied in support, refusing to take up arms against the demonstrators. After more turmoil, a number of racial and colour barriers were officially removed, and parts of the economy, particularly in the oil and banking sectors, were nationalized. That whole chain of events came to be known as the 1970 Revolution.

Part of this seismic shift took place in the cultural field. There was a grassroots movement to revitalize traditional forms in music, dance and theatre – to address the experience of the young nation by re-imagining, in contemporary terms, forms previously considered too parochial and unsophisticated to be taken seriously.

Our aim at KAIRI was to analyse and celebrate this turn towards our roots, in Trinidad and across the Caribbean. And we covered all aspects of culture: music, writing, theatre, carnival arts, photography, visual art.

Ladoo’s novels landed slam-bang in the midst of this ferment. They opened up areas missing from the canon till then. In No Pain Like This Body we were given a raw, unfiltered glimpse of a vital element in our heritage – the peasant world of the formerly East Indian indentured labourers, the so-called “coolies”, in the years when an increasing proportion of them escaped the regimentation of indentured labour on sugar and coconut estates for a peasant existence that was highly precarious for many of them. I was nagged by the question, “How come no one has written about these things in this way before?” It felt like the harbinger of a more searching, more ruthless examination of ourselves – a new kind of writing, from a new generation of writers.

In part, these novels of Ladoo’s were remarkable for what they didn’t do. Unlike most previous Caribbean fiction, they weren’t designed to fit comfortably into Eurocentric models and markets. Nor did his characters express themselves in the “perfect sentences” of a Naipaul. And though V.S. Naipaul had hinted at this kind of existence at the beginning of A House for Mr Biswas, his portrayal is at a distance and not extended. Ladoo was following his own path; not only had he staked out new content, he portrayed it with a new kind of storytelling. His writing was often cinematic. He braided stories within stories within stories. If anyone had written about these downtrodden lives before, it was with contempt or ridicule, certainly not with the stark, spare energy of Ladoo, who captured the rhythms, the mischievousness, the hurt, the humour, the despair, the cut-and-thrust of creole speech3 with unsurpassed confidence and verve.

Ladoo’s novels were gifts to our purpose; we rejoiced in their fierce originality. Add the drama of his death and the glowering cover photograph, and we were in awe. We ran lengthy reviews of both Ladoo’s novels in KAIRI; they remain, with all their youthful naivety, the most comprehensive appreciation of his writing published in the West Indies at the time.4 Sections of the Caribbean literary establishment took little notice of Harold Ladoo. If it acknowledged him at all, it was as an oddity, or a dead-end rebel.

It seemed incomprehensible to me that, quite apart from Ladoo’s literary accomplishments, no one was asking: how come, as Ladoo might have put it, “a little coolie boy from Trinidad” had, within three years, earned a university degree in Canada, published two landmark novels, was later the subject of a long poem by Toronto’s first poet laureate,5 had a prize for creative writing established in his name at the University of Toronto, and an art project dedicated to him by a major Canadian artist who had never met him?6 What would a biography of Ladoo reveal about this unlikely trajectory?

I decided to pursue the question myself. It was slow going, but in 2017, after having worked on a screenplay for No Pain Like This Body,7 and then on a six-part television documentary on Ladoo’s life and work (both of which stalled for lack of funding), I decided to tackle the legend of Harold Ladoo in a book, a new medium for me as a filmmaker, so this extraordinary story wouldn’t be lost.

I had the videotaped interviews from the stalled documentary. But apart from reviews, I’d found only two biographical sources in print form. One was a memorial essay from 1974, “The Short Life and Sudden Death of Harold Sonny Ladoo.”8 This was a touching, detailed piece by the novelist Peter Such, a mentor and close friend of Ladoo’s in Toronto. The other significant source was a 17-page poem, “The Death of Harold Ladoo”,9 by Dennis Lee, who had edited No PainLike This Body. The poem is both an elegy and a philosophic meditation, exploring the conflicted emotional void left by Ladoo’s death.

Based on these sources, which relied on Ladoo’s own accounts of his early years, the accepted story went like this. Harold Ladoo was an orphan, adopted by a desperately poor peasant family.10 He spent part of his childhood in hospitals, and was abused by Canadian missionaries in primary school. Put to work in the rice-fields from the age of eight, he later emigrated to Canada, intent on re-inventing himself as a great poet. As he would later declare in a letter to Dennis Lee, “I had no formal schooling. … I began to work when I was eight years old and I knew that one day I was going to leave the rice-fields and go out into a greater world.”11

In Toronto, the story continues, he worked as a dishwasher and short-order cook. But he soon destroyed every word he’d written and took to writing fiction in all-night binge sessions. His ambition was titanic; he was planning a sequence of 200 novels, spanning five centuries. But in August 1973 he travelled home to settle some painful family business. A week later, on August 17, his battered body was found at the side of a road about a mile from the family home, near the junction of Exchange Extension and the Southern Main Road.

The tragic, indeed grisly circumstances of his death remained shrouded in rumour and suspicion. His legacy apparently included six or seven novels he left in manuscript – which were subsequently removed by an acquaintance, and never returned.

So the story went.

Over the past half century, I’ve often been asked why I’m so obsessed with this man’s dark and violent vision. I knew that answering this question would drive me deeper into the riddle of Ladoo, and perhaps into myself.

What made Ladoo something more than just another promising Caribbean writer? It was partly his rage against centuries of brutality and denial. But it was also the stubborn and audacious originality of his work, which made it hard for many readers to pigeonhole it, let alone embrace it. He wasn’t trying to excel as one more writer from the colonies, packaging his fiction in the familiar categories of the metropolis. He was making a fresh start – telling our story the way he saw it, which at times required new approaches.

He was poised to become a significant and defiant voice of his birthplace, his people – in fact, of any region where imperial depredations have scarred the lives of the colonised, i.e. much of the planet. And his portrait of a rootless Indo-Trinidadian peasantry was so savage that even his own people shied away. But in the long arc of a complete writing life, that resistance typically subsides. In Ladoo’s case, however, the process was cut short almost as soon as it began; neither his writing nor his readers’ grasp of what he was doing had a chance to fully mature. Yet the power and tang of his vision was unmistakable, and I couldn’t shake it.

We who grew up in the optimism of Federation and Independence were traitors if we criticised Trinidad. We had to deny the negative, and promote the positive. Ladoo was a child of Independence, too, but he sensed its dark side. He experienced it viscerally, and fled Trinidad knowing it would always be there. More specifically, Independence had not embraced the Trinidadian Indian community. In the later 1960s and early 1970s, many politicised young Indo-Trinidadians saw themselves as an oppressed minority.

What was Ladoo so intent on bringing to light? Any truthful account of Trinidad must include three horrific chapters. First, the near-annihilation of indigenous peoples by Europeans, from 1498 on. Next, the abduction of Africans to serve as slaves on the sugar plantations during the 18th and 19th centuries; this lasted until slavery was abolished in 1838. And finally, there was the conscription of Indians into the near-slavery of indentured labour, from 1845 to 1917.12 When Indians were offered land grants as a means of inducing them to stay in Trinidad, as a body of reserve labour, when their indentureships ended, this did nothing to calm latent Creole hostility to the Indian presence.13 Ethnic divisions have remained endemic in Trinidad’s politics.

As of Trinidad & Tobago Independence Day, however – on August 31, 1962 – those chapters were papered over. Sealed off. Optimism and sunshine were now the order of the day; what place did recollecting such massive crimes have in the new Trinidad?

But Ladoo was having none of this willed amnesia. His calling was to strip away the façade – to tell ugly counter-truths on an epic scale. To “mash up” the colonial furniture. So I was drawn to his work, not in spite of its “dark and violent vision”, but because of it. Someone was finally getting down to business in our literature – making the fierce reckoning we needed. Ladoo had a kind of pure rage on tap – a connection to the elemental, to a raw power he rode – which he could release and wrestle into art.

What did this mean for us and our literature? That I didn’t know. But as a reader, and as a biographer, I was going to ride it with him.

This book will document the story of a young man from rural Trinidad in his audacious bid to out-write V. S. Naipaul and other Caribbean writers – in fact, to out-write all writers anywhere. It’s a story of personal courage, grave flaws and driven talent, one that deserves a place among the legends of Caribbean, Canadian, and – if only as a poignant footnote – world literature. I also hope to locate the man behind the myths he cultivated, and perhaps exorcize the glowering mask that has occupied some corner of my own life for nearly half a century.

Along with excerpts from Ladoo’s writing (many unpublished till now), and interviews with family, friends and colleagues, I lean on published reviews and memories, notably those by Such and Lee, and voices from the small community where Ladoo grew up: teachers, relatives, neighbours and others. As the years have passed, many in the community have become intrigued by this possibly famous native son. They’re fascinated, too, by the story of the whole Ladoo family, which has entered the realm of legend since the death of its respected patron, Ladoo’s father, Sonny. The family’s descent into near oblivion provides a lurid yet riveting soap opera of drama and intrigue, which has left few standing.

It is by interweaving these strands, leavened with his letters and bound by my interpretations, that I hope to build a portrait of a young man for whom Canada, and the literary circle into which he found himself catapulted, offered a blank page on which to realise his ambition, and test his concept of the writer as mythmaker and hero – both through his writing and through the personas he presented to his new friends and colleagues. And to himself.

Ladoo’s sister Meena once described him as “a knight in shining armour”. And it was this persona – the hero, with his sense of historic injustice and family loyalty – that led Harold Ladoo to his untimely death, and to becoming, in the words of one of his characters, “equal to mystery.”

Endnotes

1.KAIRI ran for half a dozen issues between 1974-75 – including artwork, creative writing and a 45rpm recording.

2.Sunity Maharaj of the Lloyd Best Institute of the Caribbean: private discussion in September 2020.

3.The term “creole” refers to the modified version of the European colonisers’ language (whether English, French, Spanish or Dutch) that was developed by the people they enslaved. There were two Trinidadian creoles – one French-African, the other English-African, both utilising African language structures and grammar. As the dominant form, the English Creole absorbed elements from the French. When East Indian labourers were imported after 1845, they adopted the Afro-Trinidadian creole that was already in place, adding their own Hindi terms for cultural items (food, plants, musical instruments etc.) particular to their traditions.

4.These reviews can be read in Appendices Six and Seven.

5.Dennis Lee, The Death of Harold Ladoo (San Francisco & Vancouver: The Kanchenjunga Press, 1976). A revised version appears in Lee’s Collected poems, Heart Residence (Toronto: Anansi, 2017).

6.See Chapter Eight, p. 93.

7.For Channel 4 in the UK, in collaboration with dramatist Tony Hall and actor Errol Sitahal.

8.Peter Such, “The Short Life and Sudden Death of Harold Sonny Ladoo”, Saturday Night (Toronto), 89, 5, 1974; and BIM(Barbados), Volume 16 No 63, 1978.

9.See note 5 above.

10.Thus the Ladoo site on Wikipedia declares that he was “born into extreme poverty,” and “grew up in an environment very much like the world of his novels.”

11.Letter to Dennis Lee, 20 November 1971.

12.For a general history of indentured immigration, see Hugh Tinker, A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas 1830-1920 (London: Oxford University Press, 1974).

13.See Selwyn Ryan, Race and Nationalism in Trinidad and Tobago (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972), pp. 190-194.

CHAPTER ONE

GROWING UP IN MCBEAN

“He used to have a massive fantasy of his own, you know, a fellow who could create a story now for now, even if something didn’t happen to him like that.”

— Ramsoondar Parasram

Harold Sonny Ladoo was born on February 4, 1945, to Sonny and Hamidhan Ladoo. They lived in McBean, a small settlement in central Trinidad, in the middle of the sugarcane-farming region. The village straddled the Southern Main Road, which connects the capital, Port of Spain, in the north, with the industrial capital, San Fernando, in the south.

Today McBean is a bustling community of over 4,000. In the 1950s and 1960s, however, it was barely a village. With only a few hundred inhabitants, it supported two stores: a dry-goods outlet, selling hardware, pulses and rice, etc; and a bar/rumshop and ‘parlour’, selling drinks and snacks.

The inhabitants of McBean and the surrounding countryside were almost completely Indo-Trinidadian, and mainly Hindu1 (with Muslim and Christian minorities). Nearly 144,000 East Indians had been brought to Trinidad after the emancipation of African slaves, to serve as cheap and “bonded” labour on the sugarcane plantations. By 1960, they constituted 36.5% of the country’s population. A few had become independent farmers, but most were still hybrid peasant-labourers, with small plots of land, but still dependent on seasonal labour on the sugar estates.

Among these Indo-Trinidadians in McBean was the Ladoo family.

The head of the family, Harold’s father Sonny, was short in stature but formidable in nature. Villagers in McBean describe him as very strong2 and very serious, a stern disciplinarian but well-known for his integrity and generosity. He was a farmer, highly respected in the community, growing vegetables and citrus on ten acres that his father and mother had been granted at the end of their second indentureship. The farm stretched behind the Ladoo home, off the Sonny Ladoo Trace3 east of the Southern Main Road. One end of the trace joined the Southern Main Road by Sonny Ladoo Road – the latter designation being one of several indications of the father’s standing in the community.

The Ladoo home in McBean

Sonny Ladoo Trace becomes Sonny Ladoo Road as it joins the Southern Main Road (2019)

The area between Sonny Ladoo Trace and the Southern Main Road was planted in sugarcane at one time, but has since become a housing development. In 2003, Trinidad’s sugar industry closed down and by 2007 the last sugar factory had shut.

Ladoo residential gardens

With the proceeds from these ten acres, Sonny, Harold’s father, rented more land. His crops of vegetables and citrus flourished, and according to Harold’s youngest sister, Meena, he was able to acquire further land in nearby Gran Couva. Villagers describe his holdings as one of the largest vegetable plantations in the country, yielding tomatoes, cabbage, pumpkin, aubergines, etc. They describe Sonny Ladoo as “the richest man in the area”, and his plantation as “the food basket of the country”.

What did this mean? The more I spoke with Harold’s neighbours and family in McBean the clearer it became that the real story of Harold and the Ladoo family directly contradicted the “accepted story” mentioned in my Introduction, on Wikipedia, and in every biographical sketch by reviewers and critics. It became evident that Harold had created an alternate personal history for consumption by his Canadian colleagues and the literary establishment.4

Harold was the third child of Sonny and Hamidhan.5 There were two older sisters, Sylvia and Ballo/Llalouci (both now deceased). After Harold came another sister, Geeta, who committed suicide in her mid-teens. Next was a brother, “Toy” or Ramesh, who, following a car accident in the late 1960s, suffered from mental illness and spent much of his later years at St. Ann’s Mental Hospital in Port of Spain. He too is deceased. Ramesh was followed by a final sister, Meena or Kusum, the sole survivor among the siblings.

There was an older half-brother as well: Cholo/Balkaran, by Sonny’s first marriage. But he lived with an aunt and, according to Meena, was not treated as part of the immediate Ladoo family. Thus Harold was the oldest male child, the number one son. When the time came, he would be expected to take over the role of Sonny, the stern, upright, yet generous patriarch of the clan. Harold first rebelled against these expectations, and then later, to his cost, tried to fulfil them.

In 1952, Harold began attending the Exchange Canadian Mission Indian School (CMI) in the town of Couva, two miles south of McBean – the only primary school in the area at the time. He was seven, two years past the recommended age for enrolment. (While five was the official age for starting school, children in outlying areas often began later, because of the difficulty of walking the miles to and from school at age five.)

Contrary to what Harold would later tell his Canadian friends, and describe in his novel Yesterdays, people who attended the school at the same time (his sister-in-law Phyllis Siewdass, and a neighbour, Hugh Ramdeen) insist that CMI was a pleasant and good school. There were no Canadian teachers, and no punishment rooms or untoward disciplinary measures. Nevertheless, Harold’s father, a devout Hindu, was not happy sending his children to a Presbyterian school, where entrance to the Canadian Mission secondary schools was conditional on conversion to Christianity, and the teachers at both levels had to be Christian.6 We can assume that Harold was aware of his father’s objections, and his criticism of the Canadian missionaries whose work was entirely focused on the Indian community. This antagonism no doubt fuelled Harold’s later portrayal of such a school in his novel, Yesterdays.

Sonny even offered to donate land for the establishment of a Hindu school in McBean. Eventually, land and funds were provided by other donors and in March 1955, the McBean Hindu School opened. Harold was transferred immediately, having just turned ten. Here is his teacher, Ramsoondar Parasram, whom I interviewed in 2003:

McBean Hindu School (2003)

RP: As a student, Harold was the third child I believe in the family if I am not wrong. So when this school McBean here opened, he came into I think the Second Standard.7 He was a sort of middle student. By the term middle, I mean average student. But he used to have a massive fantasy of his own, you know, a fellow who could create a story now for now, even if something didn’t happen to him like that, possibly that must have led to his later ability to write.

For instance, if two little boys had a little fight outside, which was a common thing in those days, then he would bring the information, he wouldn’t bring it like the ordinary fellow, you know, he highly dramatised the issue and make it look bigger than it was big, so that immediately you have to take action because, you see, the report that you get is kind of critical. But generally, other than that, he wasn’t a mischievous fellow. To say he’d go and make fight with nobody, no, not that I know of. When he left Trinidad I don’t know, ’cause I left in ’65, so after that, what he did I wouldn’t know, but up to the time I knew him in school, he was a nice fellow, friendly, good friend with everybody, except that the family had to live under the very strict rules of the father. He was an extraordinary disciplinarian, you see, and I personally believe, and I used to tell him also, that he was a little tightfisted on the children. I don’t think the father did give them much freedom.

CL: So as far as you know Harold was Sonny’s natural son. He wasn’t adopted?

RP: No, no, no. There’s no two ways, that’s his son. Now I can’t say we’d do a DNA test, …but looking at mother and father, there’s no two ways about it.

CL: But there were no rumours or anything going around that he was adopted or anything?

RP: I never knew of that, never did.

I pressed Ramsoondar Parasram on this last point, because of something Peter Such had mentioned in an interview:

He told me the story of being raised in an orphanage. I said, “Well, so was I,” because I was raised in an orphanage too. And so there was this kind of instant recognition of what we’d been through.8

It seems that teacher Parasram had Harold’s number, when he described him as “a fellow who could create a story now for now, even if something didn’t happen to him like that.”

Ranjit Ragoonanan, a school friend of Harold’s, remembers him this way:9

RR: We attended primary school together. He was most of the times a loner, but at certain times we got together. As a matter of fact, we planted those palm trees that you see in front of that school there, because we were the first batch of students that came into the school. But Harold was on kind of distant terms with his father, who was a very strict disciplinarian, ’cause he concentrated mainly on his produce and whatever.

CL: But he was a first-rate farmer, eh?

RR: He was the best in the village.

CL: What was Harold like, a regular sort of fellow?

RR: No, no, no, no. Harold would go into his shell every now and then, even in primary school. He was not violent or disruptive, but sometimes he would just get into his moods and then we and the other classmates would continue with our hi-jinks.

In the Trinidad education system at the time, students began their primary education in the first form (“kindergarten” in other systems), and then progressed through five “standards” or grades. In the Fifth Standard, normally at age 11 or 12, pupils sat for the School Leaving Certificate. Success would not only confirm their graduation from primary school, but would put them on track to be trained as teachers’ assistants and school monitors, as well as assisting them in securing other jobs.

Those who failed could repeat the exam if they remained at school. And successful students could stay on too. With no secondary school in the area, many pupils chose to remain at primary school until age 15. Those who did, entered what were called “post-primary” classes, which had curricula similar to those in the first and second forms of secondary school.

There is no record of when Harold completed primary school. But from what another friend, Sarjoo ‘Chanlal’ Ramsumair, told me,10 and given Sonny Ladoo’s support for his son’s education and the lack of a local secondary school, there is every reason to believe that Harold stayed on at McBean Hindu Primary School until age fifteen. It was within walking distance of home, the education was free, and he would cover the syllabus for the first two years of secondary school.

But like most people in his community, Harold understood that education was his only way out of a life in the small agricultural settlement. He knew he had to pursue further schooling. So, in 1960, at age fifteen, he enrolled at a private secondary school, St. Andrew’s Academy in Chaguanas, a large town ten miles north of McBean. To attend St. Andrew’s, he (or his father) would have had to pay school fees.11

Private secondary schools were concerned with only one thing: preparing students for the Cambridge School Certificate exams. “It was literally the sole business of Private Secondary Schools to provide Cambridge Certificates.”12 There were two such certificates in the 1960s: the “School Certificate” or “O (Ordinary) level,” usually attempted around age 16 or 17; and then the “Higher School Certificate” or “A (Advanced) level,” two or three years later. The latter diploma was the prize, because it fulfilled the entrance requirements for North American, British, and European universities.

Harold and his friend Chanlal went to St. Andrew’s Academy in 1960. They had to commute daily, a drive of about 20 minutes by route taxi, which cost 6 cents (3c US) in those days. St. Andrew’s no longer exists, so it is difficult to pin down exactly how long Harold stayed at the school. But we do know he stayed on longer than his friend, Chanlal, who dropped out after two terms; “Harold was brighter than me.”13

Another friend of Harold’s, Puran Ramlogan, went to McBean Hindu with Harold. He told me that Harold did not stay long at St. Andrews, leaving “after a year or two without his parents’ permission” to transfer to another private school, Chaguanas High School (no longer in existence), for a few months, before transferring yet again to Kenley’s College in San Fernando (another private school that no longer exists). There he sat London University School Certificate14 exams in history (“Caribbean, African, American, European and Ancient histories”) and literature. Puran says that Harold “had a photographic memory, and could read 6 books at a time and tell you what page he had left off reading in each one.”

Puran says Harold got a number of ‘O’ Level certificates, in history and literature, from London University, and two ‘A’ level certificates in the same subjects.15 Here is his sister-in-law, Phyllis:

PS: Well, I knew that he got his ‘O’ Levels16, but I don’t know how many. Yes, because I know he would study all night and sleep during the day because he always passed here to go to the shop there to get things to eat and he would always say, “You know I didn’t go to bed yet, I’m now going to have some breakfast and go to bed,” and he would sleep all day and wake all night studying.17 That I know for a fact.

CL: What sort of subjects was he studying?

PS: Oh! [sighs] I don’t know.

CL: You can’t remember?

PS: No. All what I know he was always reading, reading, reading, reading, you know, he and some other guys together, they always studied together.18

This story of a group of friends who studied together is picked up by another of his friends, the attorney and political activist, Lennox Sankersingh:

I recall that Kenneth Valley, former minister in the PNM government, was a close associate of his when they lived in McBean and there is a story that people talk about that Kenneth Valley and Harold and a few others didn’t get through their exams. They started school late and when they reached their late teens they took up studying very very seriously and they would study night and day and try to pass their O levels and their A levels. They didn’t have a proper school education but they tutored themselves and eventually passed their subjects.19

Puran Ramlogan was a member of the group, and he tells how “they used to meet each night at Joseph and Kenneth Valley’s mother’s home in Calcutta Road #3 and work, sometimes till 3.00 am.” Puran was in awe of Harold’s mind. With his photographic memory, Puran says, Harold could recite huge chunks of Shakespeare by heart.

Harold had a very good friend “Scotty” (Hanif Mohammed), who worked at the sugar company and ran a small shop in McBean. Puran remembers that Scotty and his wife (who was very interested in political and cultural issues) would occasionally drive the group to public lectures at the Port of Spain City Hall and Public Library. These would have been adventures for young people (mainly young men) from central Trinidad in those days; they indicate the serious nature of the study group’s activities.

Other villagers remember the group as well. In a typically macabre Ladoo touch, a cousin remembers the boys going to study in the McBean Cemetery. And from what Phyllis, Lennox, Puran and Meena report, Harold eventually passed his school certificate examinations at both levels. This would later help him in gaining admission to the undergraduate programme at Erindale College in the University of Toronto, where he would meet up again with Lennox Sankersingh and Ken Valley.

What did Harold do with himself in these years, apart from studying with the group and sitting his School Certificate examinations?

In the normal course of events, his family would have had first call on his time. His father’s agricultural enterprise required constant and intense work. So when he was not in school, he might have been expected to spend long hours planting and weeding and harvesting. Puran Ramlogan (who lived next door to the Ladoos) told me that Harold did no work in the fields. He attended school, and he studied independently, and that was his job.20 His younger brother Toy and his older half-brother Cholo didn’t escape fieldwork, and Puran too was enlisted to work for Sonny. (He was paid $3.00 a day – about $1.75 US.) This suggests that Sonny recognised his son’s intellectual ability and supported his education as a means of improving his employment prospects and his future as potential heir to Sonny’s estate. This (and Sonny’s later assistance in financing Harold’s emigration) would have placed a serious obligation on Harold, one that he rebelled against even as he knew he couldn’t avoid it. The young Harold’s uneasy relationship with his powerful and successful father would continue to be a significant and telling element in the years to come.

What opportunities for entertainment and fun did young people in McBean have in the 1960s? Chanlal told me that after Harold had received the obligatory permission from his father, he would go to Harold’s home, where they would wrestle and lift weights under the house.21 According to Chanlal, Harold was thin but strong. He particularly loved movies featuring “strongmen” like Steve Reeves,22 often “breaking biche” or playing truant from school to do so.

Teacher Parasram told me there was not much in the way of organised activities for young people at that time, other than the cricket offered by the McBean Sports Club where teams from different streets in McBean would play against each other. But, again, Puran was adamant that Harold played no sports, though as boys they would ride bicycles around the area, even as far as Chaguanas or Couva. Beyond that, the elders were very cautious about allowing their young people to go outside the community on beach or river excursions, but the McBean Hindu Primary School did organise tours to places of national interest. Still, according to Chanlal, he, Harold and their friends would walk or bicycle to the nearby Carli Bay beach or to Couva River, over five miles from McBean.

Carli Bay, Couva 2019

Another factor affected leisure activities. At that time, the political landscape and social structure of Trinidad & Tobago were undergoing rapid changes. The People’s National Movement, which came to power in 1956, had its base mainly among the population of African descent, leading the country to full independence in 1962. Indian Trinidadians, feeling marginalised and somewhat besieged, looked inward for their entertainment. This included singing and dancing at social and religious events, pujas at the mandir,23 occasional recitals of traditional devotional songs.24 Harold would also have been familiar with some of the Indian classics such as the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita, as these texts were well known among the Hindus in Trinidad (often in English translation), where they were chanted at pujas25 and dramatized in the annual ‘Leelas’26 in some villages. Harold’s friend, Chanlal, also told me that Harold liked to attend lectures (in English) by visiting Indian swamis.

And, probably most frequently, there were trips to the cinema, which was increasingly programming Indian movies subtitled in English, as the aging population that could understand Hindi dwindled.

Harold went to the movies fairly often. There were two cinemas in Couva, the Metro and the Carib, as well as the Jubilee in Chaguanas. San Fernando (18 miles to the south) boasted at least eight cinemas. According to Chanlal, apart from Harold’s penchant for strongman and legendary-hero movies, like Steve Reeves, they mainly went to see westerns. And of course there were the serials designed by Hollywood for juvenile audiences, which V.S. Naipaul describes disparagingly as “one of the staples of adult entertainment”27 in Trinidad. Though television had been inaugurated on Independence Day (1962), few homes in McBean had TV in the 1960s.

Newspaper advertisement in the 1960s for the Metro chain of cinemas showing Indian movies, and the one in Couva showing a Western double feature.

Chanlal describes Harold as a loner, quiet, always having a book or comic book with him. This would have marked him out in McBean. Trinidad at that time had perhaps two shops devoted to selling literature other than school texts, and these were in Port of Spain and San Fernando. In a society not known for its reading habits, to grow up as a reader sets you apart. But as we hear from his sister-in-law Phyllis, Harold was a reading evangelist: “He was always reading, always encouraging us to read too.” The swaggering image Harold presented is nicely captured by Chanlal: “He always had a book or a comic in his back pocket.” This image also suggests the type of books Harold was carrying around, books that could be crammed into a pocket. These would have been “dime-store” novels of crime, romance, and westerns with paper covers.

Being a solitary and voracious reader can foster lively internal fantasies. Harold was fascinated by the worlds of swashbuckling and gun-toting heroes and villains. But in the process of absorbing those stories from books and at the movies, he evidently developed a clear appreciation for the techniques of storytelling on the page and screen, resulting in writing that told its stories predominantly through action.

He had to read more serious books for his School Certificate exams. One subject would have been English literature, which required reading set poetry, novels and plays. In the 1960s, teachers in the Trinidadian school system preferred to select nineteenth-century literature.28 Thus Harold would have been familiar with poetry by Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Tennyson and Walter de la Mare; novels by Austen, the Brontes, Dickens, George Eliot; and of course, plays by Shakespeare, often Macbeth or Julius Caesar. These texts could have been purchased from bookstores, most of which depended on filling school booklists to be sustainable. Since bookstores were very limited in what they offered and with financial resources limited, Harold did not buy many books but haunted the available libraries. One library he and his study-group friends frequented was the American Library in Port of Spain (part of the US Information Service, attached to the embassy). It provided a quiet, air-conditioned space, which also had information on educational opportunities in North America.

There were small branch libraries, first in Couva (a one-room library with few books), and later in Chaguanas. Chanlal told me Harold used the library in Chaguanas. And Meena and Puran told me he also went to the Carnegie Free Library in San Fernando, where he was attending school. Comic books featuring superheroes like Batman and Superman could be purchased from most booksellers and even grocery stores, as could popular novels like those by Mickey Spillane and Louis L’Amour, and other lurid thrillers and westerns.

Caribbean literature would have been hard to find in central Trinidad in the 1960s, but V.S. Naipaul, being Trinidadian, was better known. Harold would almost certainly have read one or more of his books – especially since Naipaul’s best-known novel, A House for Mr. Biswas (1961), is largely set in nearby Chaguanas.

A bright, self-motivated, well-read young man who lived in a world of books, comic books and action-hero movies, who felt trapped in a rural community in the middle of a small island, and was determined to make a name for himself in the wider world: this is not an unusual circumstance in the history of literature.

Since the 1950s, when Caribbean literature began to flourish, aspiring writers had journeyed to the metropoles – whether England, France or Spain – in order to become established: to learn their craft, and make their mark. Not only to be published, but also to escape what they saw as the cloying, insular and claustrophobic life in the colonies.

At that time, there was only one short-lived Caribbean publishing house in Jamaica (Pioneer Press) and four significant “little” literary magazines: Kyk-over-Al in British Guiana, Bim in Barbados and more occasionally Focus in Jamaica and Clifford Sealey’s Voices in Trinidad (1964-1966). For anglophone writers such as V. S. Naipaul, George Lamming, Sam Selvon, Michael Anthony, Edgar Mittelholzer, Wilson Harris, Andrew Salkey, E.R. Braithwaite, and many others, this meant moving to the UK – usually London – in order to have access to publishers and to the fees that the BBC Caribbean Voices paid for scripts and for reading.29

As Shiva Naipaul (the novelist younger brother of V. S. Naipaul) said in an interview with the BBC shortly before his untimely death in 1985:

Escape; that had always been the goal, and academic success offered the only hope of its fulfilment. Education under these circumstances became a barely controlled frenzy. … A popular theme of local folklore centred on those unfortunate to have failed by a mere mark or two to win a scholarship and then gone mad or bad. … However, let me not be misunderstood, I did not hate the island, my life there was not intolerable, it was just that its constrictions, its complicity, offered me no vision of myself beyond a certain point. One grew out of it as one grew out of one’s clothes. If I constantly dreamt of escape it was not because I was especially perverse or especially wilful, it was because there genuinely seemed to be no alternative. I wanted to be neither mad nor bad.30

Or as V. S. Naipaul wrote in The Enigma of Arrival (1987):

My real life, my literary life, was to be elsewhere. In the meantime, at home, I lived imaginatively in the cinema, a foretaste of that life abroad. … it was painful, after the dark cinema and the remote realms where one had been living for three hours or so, to come out into the very bright colours of one’s own world.31

In the late 1960s, the debate about having to leave the island to become a writer in the international market was well under way. The novelist Earl Lovelace and the poet Derek Walcott (later to win the Nobel Prize for Literature) were adamant that they would stay on-island and make it as writers; but both had already been published in the UK and the US. Harold, isolated in rural Trinidad, would not have been aware of this debate, but might well have been aware of the exodus in the 1950s.

As he would later declare in a letter (already quoted in the Introduction) to Dennis Lee, on 20 November 1971:

I had no formal schooling, I had no money or encouragement, but I had the capacity to endure. I began to work when I was eight years old and I knew that one day I was going to leave the rice-fields and go out into a greater world. It was that thought that kept me alive.32

This statement is critical in answering the question, “Why was Harold so focused on leaving McBean?” The image of him working in the fields from the age of eight is typically over-dramatic, and another example of Harold’s conjuring alternate histories for himself, since he did attend school (and his father planted very little rice, mainly for the family’s use). Nevertheless, it holds the kernel of his motivation.

For Harold, with an older sister in Toronto who could sponsor him as a landed immigrant to Canada, the UK was not the first option.33 But he had a suitcase full of writing. The outside world awaited the emergence of a new writer. He was intent on escape from McBean. Very intent.

But first he wanted to get married.

Endnotes

1.85% of indentured labourers were Hindu and 14% Muslim.

2.“He could carry a sugar bag [450 lbs] on his back, and in competitions he was known to lift a sack of rice [162 lbs] with his teeth.” Interview with Puran Ramlogan by Christopher Laird, 2021.

3.“Trace” – a path or track.

4.Harold’s self re-invention will be examined in Chapter 10, “Who Was Harold Sonny Ladoo?”

5.Harold’s friend and mentor in Toronto, Peter Such (in an interview with Christopher Laird in 2003), says he saw Harold’s birth certificate, and it stated he was ‘illegitimate,’ which Peter thought supported Harold’s contention that he was adopted. But an “illegitimate” status on birth certificates when Harold was born would have been common, because it wasn’t until after 1945 that the colonial administration recognised Hindu marriages.

6.“Whilst many parents are not willing to have their children baptized, yet they are desirous of having them attend the Mission schoo1”: Miss Kirkpatrick, a missionary, to the Presbyterian Record in 1891.

7.Normally the Second Standard (Grade Two) would admit students of about 7-8 years old, but Ramsoondar Parasram says it was not unusual in those days for students to be older, since they started school much later.

8.Interview with Peter Such by Christopher Laird, 2003.

9.Interview with Ranjit Ragoonanan by Christopher Laird, July 2003.

10.Interview with Sarjoo ‘Chanlal’ Ramsumair by Christopher Laird, 2019.

11.Private secondary-school fees varied from $.50 to $5.00 a month (worth 0.30c and $3.00 in $US at that time).

12.See Brinsley Samaroo, “The Presbyterian Canadian Mission as an Agent of Integration in Trinidad During the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries”, Caribbean Studies, Vol. 14, no. 441.

13.Interview with Sarjoo ‘Chanlal’ Ramsumair by Christopher Laird, 2019.

14.Though the national education system prepared students for the Cambridge School Certificates, the equivalent certificates from London University, London University School Certificates, were available to students sitting privately or through the Extra-Mural classes of the University of the West Indies.

15.His university transcript later records that he presented Ordinary Level (‘O’ Level) G.C.E. Certificates in English Literature, English Language, History of the British Commonwealth, Religious Knowledge, and Advanced Level (‘A’ Level) certificates in History and the British Constitution.

16.The Cambridge School Certificate and Higher School Certificate were later superseded by the General Certificate of Education O level and A level, both of them run by Cambridge (in the state or assisted schools) or London Universities (for the private and University of the West Indies Extra-Mural schools).

17.Harold’s penchant for working/studying by night became his routine for writing his fiction in night-long ‘binges’ in later years.

18.Interview with Phyllis Siewdass by Christopher Laird, 2003.

19.Interview with Lennox Sankersingh by Christopher Laird, 2019.

20.“Harold never worked.” Interview with Puran Ramlogan by Christopher Laird, 2021.

21.Most houses in the area were traditionally built on tall stilts, and the open space under the house – the bottom-house – would be used for relaxation in a hammock, informal gatherings and other activities which did not require access to the living quarters.

22.Stephen Lester Reeves was an American professional bodybuilder, actor, and philanthropist. He was famous in the mid-1950s as a movie star in Italian-made peplum films, playing mythic characters such as Hercules, Goliath, and Karim, in The Thief of Baghdad.

23.Hindu prayer ceremonies and rituals at the temple.

24.A neighbour, Hugh Ramdeen, told me (interview 2019) that Harold “liked to talk philosophy, knew a lot about Hinduism and liked to attend lectures – mostly by visiting Hindu Swamis.”

25.Hindu religious ceremonies

26.‘Leela’ or ‘Lila’ – a ‘divine play’. A play based on classic Hindu religious texts often performed by and for the community in open spaces.

27.V.S. Naipaul, The Middle Passage:Impressions of Five Colonial Societies (London: Andre Deutch, 1962), 59.

28.According to people I interviewed who were teachers in the area at the time, like Pundit Ramsoondar Parasram, St. Andrews Academy would have had few qualified teachers; many of them may have been school leavers themselves. The syllabus they chose to teach would have been influenced by what they themselves had studied.

29.See Glyne A. Griffith, The BBC and the Development of Anglophone Caribbean Literature, 1943-1958 (London: Palgrave, 2016)

30.Shiva Naipaul, Beyond the Dragon’s Mouth, BBC television, 1984

31.The Enigma of Arrival (London: Viking, 1987), 108

32.Letter to Dennis Lee, 20 November, 1971.

33.“The arrival of the Canadian Presbyterian Missionaries on the Caribbean islands during the colonial period laid the foundations of the migration of the Indo-Caribbean people to Canada. The Indo-Caribbean people were encouraged by the Canadian Missionaries to pursue higher education in Canada by offering them scholarships. The history of migration of Indo-Caribbean people in Canada can be traced to the early nineteenth century but it was only after the introduction of the ‘Point System’ in 1967 that the Indo-Caribbean people began to arrive in Canada in significant numbers.” Canadian Diaspora: Surviving Through Double Migration And Dis(Re)Placement, Ramchandra Joshi and Urvashi Kaushal. Journal of Indo- Caribbean Research in Vol. 8, No. 1, 2013.

CHAPTER TWO

LEAVING MCBEAN – IMAGINING TOLA

“He say if I don’t married to him, when I walking down the bridge somewhere there, the corner of the road, he’ll take a gun and shoot me.”

— Rachel Ladoo

Harold set his sights on a young widow, Rachel Singh. She was a year older than him, and lived close by in McBean. Her background was striking. Her father, Ramkaran Singh, was tall and fair, a cricketer and a tailor to the prime minister. He had children by two sisters at the same time, pairs of children of the same age. One was Amin Khan, Rachel’s mother.

In 1957, when she was 13, Rachel married Jewan Singh, who had a reputation as a mouth-organ player. They had three sons, followed by a daughter, Deborah. They separated in 1961. Her second partner was Absal Mohammed, with whom she had a son. In 1963, however, Absal was killed in a hit-and-run on the Southern Main Road.1

Rachel was now a widow at 19, with five children.

In a 2002 interview with Ramabai Espinet (the novelist and colleague of the author’s), Rachel recalls how she married Harold in 1968, despite an impediment to the marriage:

Rachel Ladoo (2002)

RL: Like he used to come over at our place every evening and one day he said he liked me and I said, “No, I don’t like you because we’re family and I can’t have feelings like we like each other, I like you as family, I must be in love with you to get married.”

He said, he don’t care he has to get married to me. I said, “No.”