6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

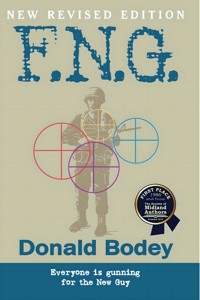

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Reflections of America

- Sprache: Englisch

Everyone is gunning for the New Guy

Gabriel Sauers of Two Squad is a soldier, newly arrived in Vietnam--a country too beautiful to invite so savagely unreal a war. But Gabriel won't be a New Guy for long. He'll go through incoming mortars, he'll see the enemy alive. He'll wander through a hell that will turn the green recruit lucky enough to survive into a death-hardened veteran, longing for nothing more than a return to the world of hot baths and cold beer, no bullets, and no noise. Now, 40 years later, he is grappling with an action on the verge of his grandson Seth's deployment to Iraq that will change both their lives forever.

Critics Praise Don Bodey's F.N.G

"One of the most hard-hitting of all the vietnam novels" -- The Boston Herald

"A powerful social document and a well-written, deeply moving first novel...highly recommended" --The Library Journal "Raw, profane...a candidly moving portrayal of the average American soldier in Vietnam, who often found courage when he did not seek it--but little of anything else." --Chicago Sun-Times

"The day to day grind, beautifully and touchingly rendered by...a Vietnam veteran, is told with an unrelenting accumulation of detail." --The New York Times Book Review

"Bodey packs considerable emotional freight...into a style that remains deliberately supple, cool, and declarative...An impressive novel." --The Cleveland Plain Dealer

"A harrowing vividly written account of hell with a leavening of light moments. A revelation for one who wasn't there. Painful for those who were." --Bob Mason, author of CHICKENHAWK

"All Quiet on the Western Front drives its readers to the front of World War I. F.N.G helicopters its readers to a new front: Vietnam." --Bestsellers

(an Imprint of Loving Healing Press)

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 584

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Ähnliche

REVISED EDITION

F.N.G.

Donald Bodey

F.N.G., Revised Edition

Copyright (c) 1985, 2008 by Donald Bodey.

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

First Edition published in 1985 by Viking Penguin Inc.

Revised edition published in 2008 by Modern History Press,

“Yes Sir, Yes Sir, Three Bags Full” also appears in Made in America, Sold in the ‘Nam, 2nd Ed.

“Present Day” also appears in More Than A Memory: Reflections of Viet Nam

_____________________________

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bodey, Donald.

F.N.G. / by Donald Bodey. — Rev. ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-932690-58-3 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-932690-58-1 (alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-932690-59-0 (trade pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-932690-59-X (trade pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Vietnam War, 1961-1975–Fiction. 2. Veterans–Fiction. 3. Grandparent and child–Fiction. 4. Iraq War, 2003—Fiction. I. Title. II. Title: FNG.

PS3552.O36F2 2008

813'.54–dc22

2008009833

Modern History Press is an imprint of Loving Healing Press, Ann Arbor, MI

Dedicated to my father's memory and to my mother; to all my brothers—blood and spiritual; to each and every surrogate mother, wife, sister I've needed; and for Mike Morgan, KIA, because I could never keep the promise I made.

Let me repeat: to my dad and my mom, brothers, wives.

to Morgan, who got wasted, no matter how you look at it, &

to Neil Myers, who helped me so much as a writer

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank: Anybodey who lets me sleep with her. Bob, a brother/keeper. Bunch. Ciara. Clare Patano, for giving me half the world. Ed, for every bed you ever gave me. Peters, for the 40-year-old pizza. Sky, my boy, for your future. Sue, for a past. Victor, for the second chance. Cover design for this edition by Gary Fabbri.

Critics Praise Don Bodey's F.N.G

“Vietnam veteran Donald Bodey captures the fears and apprehensions of every infantryman… if you like adventure, a true picture of combat and the chance to look into the combat veteran's mind, F.N.G. is your kind of book.”

—Mike Mooney, Stars & Stripes Korea Bureau Chief

“F.N.G. makes me glad I wasn't a grunt. Bodey's unsparing eye illuminates detail after detail of the precarious life they led. Dirt, smells, sounds, fears, sudden death, friendship, drugs, bugs, each incident etches itself vividly in the reader's consciousness.”

—Bob Mason, author of Chickenhawk

“When I first read a draft F.N.G. in 1980, it rang true and it's still on target for the thousands I have worked with over the last 28 years. It still rings true today with each new wave of combat veterans, wherever they are returning from. The bottom line is that war still sucks and the damage seems unending if one follows the ripples to where they ultimately arrive.”

—Rick Ritter, MSW, Ed. of. Made in America, Sold in the Nam

“A vivid, frequently moving book that takes the reader on a trip into the reality of war. The reader suffers with these men, and sometimes even smiles at their antics as they slog through the jungles. This is a hard book to forget.”

—James Hill, Rocky Mountain News

“Bodey brings back alive the particular horrors of that particular war so well that we participate in it with frightening directness. His prose is exacting, his rendering of evocative details thoroughly accomplished, and the pacing absolutely absorbing.”

—Barry Silesky, Chicago Magazine

“Bodey writes in an extremely realistic vein…that gives F.N.G. authenticity and strength. All in all, a moving book, both an exercise in memory, and a bittersweet exorcism.”

—Kirkus Previews

“A documentary-style, first-person account of one soldier's year in the mud-soaked dugouts near the Cambodian border… reading the book is as close as any of us would want to get to the experience.”

—Robert Merritt, Richmond Times

“Bodey's first novel captures the reader. All Quiet on the Western Front drives its readers to the front of World War I. F.N.G. helicopters its readers to a new front: Vietnam.”

—Robert E. Shimokoski, Jr., Bestsellers

“Raw, profane…a candidly moving portrayal of the average American soldier in Vietnam, who often found courage when he did not seek it—but little of anything else.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“The day-to-day grind, beautifully and touchingly rendered by…a Vietnam veteran, is told with an unrelenting accumulation of detail. His characters are flesh and blood.”

—Charles Salzberg, The New York Times Book Review

“Bodey packs considerable emotional freight…into a style that remains deliberately supple, cool, and declarative… An impressive novel.”

—The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“The publication of this work conveys this importance this author places on accurately portraying the war through the eyes of an infantryman.”

—Illinois Daily Herald

“A very, very interesting story, you should really check out this book. There's a need for this story and stories like this to surface and be read today.”

—Juanita Watson, Inside Scoop Live

“This is strong writing, convincing, and compelling. It should be required reading for every member of Congress and everyone with influence in the military. F.N.G. is an important reflection on a period in American History.”

—Richard R. Blake, Reader Views

“If you were only going to read just one novel about the Vietnam War then this would be my choice and my recommendation! It is a most compelling account and will not an easy book to forget or put down.”

—William H. McDonald, Viet Nam vet, author, and past president of Military Writers Society of America (MWSA)

“F.N.G. is a book everyone would benefit from reading, especially families of military men and women, so they will understand what their loved ones go through. Very few war novels would receive such a recommendation from me.”

—Tyler Tichelaar, author of The Marquette Trilogy

Contents

Chapter 1 – Present Day

Chapter 2 – Arrival

Chapter 3 – Two Squad

Chapter 4 – Bushwacky

Chapter 5 – Jumping Off

Chapter 6 – LZ Pansy

Chapter 7 – Yes Sir, Yes Sir, Three Bags Full

Chapter 8 – Point

Chapter 9 – Baptism by Flare

Chapter 10 – LZ Rain

Chapter 11 – Peacock's Bird

Chapter 12 – The Donut Holes

Chapter 13 – The Yellow Brick Road

Chapter 14 – Old Folks’ Home

Chapter 15 – D.E.R.O.S.

About the Author

Glossary

“I can forgive, but if you ask me to forget, you ask me to give up experience.”

—Louis Brandeis

Flakes, snow saucers, amble down, like they have a mind and don't want to land. In the streetlight a hundred feet away they float like birds bobbing in small waves. But here, in the forty-watt garage light, they dither in dizzy scribbles, ten feet off the ground. Some hit the old dog's nose and some her filmed-over eyes, but she lies there and looks up as though she isn't missing a thing.

When I say her name, she raises her head and a few flakes coast onto her yellow brows.

Jesus, Seth could be in Iraq in a week.

Except, I'm going to give him a million-dollar wound. I don't want him to come back like I came back from Nam.

The refrigerator whines and the old-water smell of this place passes through the door I'm standing in. The snowfall is thinner. Mary's bathroom light stabs the darkness, a train whistles two miles away, a weak god blowing on a bottle. In Nam, when they asked me what I missed about home, I said a train whistle.

The sparkle of the TV turns nearby snowflakes purple and green for an instant, the dog turns her nose that way. How many times have Seth and I sat in the woods together, watching it snow? I lean against the doorjamb, watch, and rub the silver dollar in my pocket. The markings are all gone, it's thin. My dad was hoeing a potato field, seventy years ago, and got bit by a coral snake but didn't die, so the man told him he earned a whole dollar that day. He carried it forty years and gave it to me when I went to Vietnam. I flipped it for body-bag duty, sucked on it in fear, kept it in my boot for 400 days, and in my pocket ever since.

The transformer in the alley hums with a different tone through the flakes. Someone in the neighborhood is burning plastic. Mary's TV sends game show laughter out here. Everything I see or hear seems bad.

Everything depends on the hunt. I remember telling him about killing animals, explaining the reasons: him as tall as a fencepost when we packed cheese, crackers, radishes, and sat until he had a shot. Little female squirrel the color of dead leaves, in a limb crotch. The sun had broken through and he was asleep against me, gun beside him, cracker crumbs on his cheeks. Woke him up and pointed and he's ready. She tumbled and never moved. He held her by the tail all the way home. Mary cooked it for breakfast.

Taught him to shoot same way my dad taught me. Put a silver dollar on a fence post and use a rifle. He never hit it, but he learned to breathe and squeeze the trigger. They don't tell you that in Boot camp; they tell you to kill. They were right about that.

When the dog raises up and moves I know she hears Seth's car. I get my cane down and we meet in the driveway. Bigger and stronger than I've ever been, a smile that eats half his face. He picks the dog up like a pillow and her long yellow tail sweeps the air, her tongue searches for his chin. He lays the dog on the car's hood, sweeps the 'phones off his head.

“She lose weight again?”

“Must be down to eighty pounds.”

“Mom awake?”

“Getting ready for work. We still hunting?”

“Can't wait.” Buries his face in the dog's stomach, lifts her to the ground.

Being in this garage is safe. A thousand nights in this chair, its broken spring pressed against my back. Seth'll be waking up in an hour, daylight another ninety minutes, and the hunt is on. What do I say? I'm going to shoot him for my own sake, but how do I explain that?

Electric heater like orange teeth, sound of buzzing flies. Enough warmth for my feet. Agent Orange. Millions of gallons into the jungles to eat away their hiding places. Then it got into the rivers we drank out of, into us, and after years began to eat us from the inside. Some guys’ liver, stomach, prostrate gland. Mine, so now I wear a diaper.

Throw-rugs on the clothesline wave beyond the dog. Her head is tucked onto her forelegs and she lies there burbling. Each breath flaps the skin of her lips, a burble. I wonder what color prison diapers are? When I breathe and squeeze this trigger the bitterness will leave me as, sure as a round leaves a barrel. Forty years of regret in one shot. Emancipation, I'm sure of it.

Trembling a little, and when I get up to walk it off she turns towards me, flips her pancake ears up, quits burbling. A mouse dashes under the lawn mower, starts her nostrils twitching, she shifts her weight, rolling marble eyes.

There is a connection to ritual through guns. Dad and I had our rituals, Nam was full of them, all connected to guns. I was never away from my rifle, knew its serial number, trusted it, depended on it, guarded it. Seth and I have ours too. I didn't touch a gun for twenty years, until he was old enough to hunt. Then I wanted to kill something, or at least to shoot again.

The bathroom light goes off.

I carry my dad's Savage automatic, and when I pick it up, it's like shaking his hand. We hunted a lot when I was young. Never after Nam. It's weight makes me feel like he's here. I break all the rules and all the laws because it's been loaded for forty years. At times I've thought of swallowing its load, but today I feel just the opposite, I have plans for it.

I rack a set of rounds through it and they bounce off the concrete with a doink, bring her ears up like gallery targets. Its mechanism is loose and loud, but there's no slop to it. I load Seth's pump and run a set through it too. Tight and quiet, like a new M-16. Sometimes in Nam I wondered who carried mine before I did. There's a grip in that plastic stock that says it's been held, something psychic that says hello! You never get away from your gun, so when you come back to the World you feel its absence, and you still think you're going to get killed. What is that? Cowardice?

I don't hear him, but she does. Her head jerks towards the house, then her tail wags once, yellow Spanish moss. He's barefooted, carrying his boots, like there is no snow. Piano key smile, ruffled hair, he stands in the doorway and pushes his feet under the dog's belly

“Here.”

He catches it in his boot, dumps it on the dog's back.

“What? Why give it to me?” he says, pulling on a boot.

“In case you need it.”

“What for?”

“You need,” I say, and look at him quick, “to give it back to me someday.”

“If I lose it over there?”

“Even if you don't go.”

“You went.”

We load the gear, are hardly a mile away when he falls asleep against the window. The road is icing up. The snow, now fine and wet, and the ample moonlight, his rhythmic snoring, this smell of dog in the truck seat, it all seems like part of the ritual. We ride like that for twenty miles. I'll tell him at breakfast: You get back and know going was the wrong thing for you to do.

“Did you kill anybody? He leans his elbows on his knees, his forehead on the dash. “I mean, you know, dust ‘em?”

He sounds like a boy and all of a sudden I'm calm. I'll hurt him a little bit and he'll be better for it.

“How much of the truth do you want?” It just comes out. “I tried to.” I raise one finger, “And they tried to kill me. I didn't go over there to kill somebody. Maybe that's what's wrong.”

We're at the restaurant. He bends to tie his boots. The parking lot is slushy and we lean into the wind. Inside is a bright box, a few tables of hunters. There's a din of talking, the overhead speakers, the dishes banging around, smell of dirty flannel and pancakes. He starts to sit down but I signal to give me that seat.

“Why?” he asks.

“I can see the door. I've got your back.”

A chunky busboy begins cleaning the table behind him.

“Nam?” Seth raises his eyebrows. His lips look tight, he suddenly seems older.

“I guess. That's where it started. Anyway, we're going deer hunting.”

“I want to know.”

“It screwed me up.”

“How?”

“That's a long story.”

“Tell me.”

The busboy moves to another table. He's a good-looking kid, maybe 15 years old. His mother runs the place. Our waitress is a woman as old as I am, who has never hurried in her life. Round face in a scowl, order book in her left hand and that elbow resting on the side of her stomach. She takes our order and goes through the kitchen door. Seth stretches out in the booth and blows smoke rings. My hand shakes when I fiddle a cigarette out. This is the time to talk to him.

“If I tell you about Nam, I have to start with being an F.N.G., when I was your age.”

“What's F.N.G.?”

“Fucking New Guy. It's somebody who's never been shot at.”

“That's me,” he chuckles, “a fucking new guy.”

“Well,” I hold his eyes, “when I shoot at you out there today, you'll be done with that.”

This place was originally a gas station. The front wall is big plate glass windows, and they are shaking in the wind now, snow coming hard, the faintest distinction of the horizon beyond the snow. Whenever the door opens there's a rush of cold that brings in some snow and blows napkins onto the checkerboard floor. Five guys at the other end of room are laughing, their orange hats like big fish bobbers. The busboy takes a mop to the tracked-in snow and he's smooth with it, like a dance. I'm waiting to see if Seth heard what I said. I get a smoke ring as big as a doughnut that we both follow until the heat draft scatters it.

“What's it like to get shot at?”

“Depends on whether you know it or not. Could be like hitting one of those homemade things in Iraq.”

“Yeah. You'd live in constant fear of hitting one of those, if you went…”

“If?”

“Yeah.” I act like I'm looking outside for the first time. “That wind is gonna cut us in two, you know?”

The whole room seems noisy when she comes with three plates on one arm, two saucers of toast in her other hand. The gravy sends up a plume of steam, my stomach rattles. This is part of our ritual, breakfast together.

If you go to Iraq, you take a chance on never being involved in love because nobody can love you if you don't love yourself. I'll tell him that after I shoot him. I'm shooting him for love, but I don't need to tell anybody.

My hands are shaking. I try twice before I can get the fork to my mouth. I breathe, look at him, wonder if he sees.

“How old were you when you went, Gramps?”

“Your age.”

“Were you scared?”

“Sure. Are you?”

“Yeah.”

Since he was a baby, he's always been smiling, or ready to. But now the corners of his mouth are low. He glances at me, then lowers his face to meet his fork. It's odd, for him.

“How's your girl?”

“She's fine,” he says. Still looks at his plate and chews. “She's scared too. She doesn't want me to go. She cries about it all the time.”

His girlfriend for five years. I can see her round face, big eyes, perfect teeth, a scar the shape of a sickle by one eye.

Now the eastern sky over his shoulder has shifted color. The horizon is something like a TV screen the instant the set is switched off. Hunters from another table pull on jackets and leave, talking about who'll be sitting where. Their conversation fades. My thinking is loud.

“You don't have to go.”

“You did,” he says, real quick.

“That was a mistake I made. Most of my life since then has been tough because of that.”

“Why?”

“I knew right from wrong when I was drafted. The Army changed all that–Basic Training, Infantry Training, they told me, everything my mom and dad taught was wrong. Told me, all day all night for five straight months.”

Snow falls into the restaurant lights like a mass of dead moths. I want to get to the woods. I want to shoot him, so he can't go.

“Tell me about being over there, gramps.”

“Hot. Rained all the time. Dirty.”

He looks at me out the corner of his eye, gets into his jacket, drops a tip on the table.

We'll do the hunt. I'll shoot him coming out of the woods.

~ ~ ~

Ten miles to the woods, past barnyard lights, a dead buck beside the road, antlers in the air. Country music, heater fan whispers against the windshield. The horizon has begun to bleed gray, a line across the white fields like a moustache. Seth lights a cigarette, rides smoking with his window cracked. I can smell the gun oil from the back seat.

I wonder if the old farmer is awake.

The barn has a very small room in it, barely warmed by a kerosene heater we can smell when we pull open the door. He's there, waiting in a chair that looks like home to mice, beat-up faded fabric, it's missing most of one arm.

“Morning.”

Wearing a dirty hat with a drawing of a tractor. There's a gap between two bottom teeth big enough to drive the tractor through. His whiskers are a week old. The hair growing in his ears is the color of smoke, but the rest of his hair is new snow. The two ratty coats over a pair of overalls look too new to be his.

“Seen ‘em moving?”

“Not much, too warm to rut, I think. Who's this young fella?”

“My grandboy. He's been here before.”

“I forgot. I forget everything but how to put my pants on, and mostly don't take them off at night anymore. Piss in a thunder jug like I did growing up.” He smiles. “Saves my septic tank a little, wintertime. Lonesome, just me and my cats.” Crusted face, think skin barely covering his long jawbones.

Walking towards the woods, the sky light is more than a line, less than a ribbon. No sound but our canvas pants legs and the crunch of boots on snow. He's just a silhouette, a guy walking with his gun ready.

I could shoot now. A twelve-gauge slug is the size of a roll of nickels, pure lead. If I get him in the leg somewhere it'll break the bone. The closer to the barn the better, but I can't let the old man see. I'll let him get ahead of me, halfway across this field, about where we are now. I'll trip, my gun will go off.

The first real color comes on a straight line through a break in the trees, pale blue. My dad was a big strong man but when I see that blue light I get the feeling that he's here, small, sitting in my lap. Like a cartoon where a guy's conscience is on his shoulder.

Seth and I have talked about how we watch the edge of daybreak spread along the ground. Red squirrels scurry, dance, chatter, bother the peace. A female cardinal moves through the tree tops, the coo of ground doves comes and goes like a mantra. Then, a doe and two fawns cross the creek. My heart races. She's big, the fawns are yearlings. If I shoot her they'll hang around awhile, then run away, on their own. She stands a moment, moves enough to put a tree between us, changes direction, stops. The snowflakes and the fawns’ spots look about the same size. I tap my barrel on the stand and she's gone, short tail up, a white flag that the fawns follow up the hill.

Train whistle a mile away. The wind stings the tips of my ears, blows cold through my wet diaper. A few brown leaves lie on top of the snow, red squirrel trails scrawl dotted lines from stumps, downed limbs, burrows. I meet Seth's footprints a hundred yards from my tree: giant splotches, evenly spaced. Neverleave perfect tracks again. He'll limp. If it's not a good shot, he might only leave one footprint.

He's sitting on a stump, orange hat puffed up on his head, gun leaning beside him. A hawk sails the wind at the tree line. The wind finds the hole between my hat and coat, makes my eyes water, bowls into my diaper, feels like my crotch is packed with snow. Agent Orange. I finger the trigger, check the safety. My hands are cold, legs shaky. I don't look at him. Fifty feet away I stop. He's looking at me but I don't look at him. I check my trigger housing, where I put my right thumb, the choke setting, the grain pattern in the stock. I feel the gun's weight, its shape.

Through one eye, through the sights, I see him smiling. Then he sits up straighter and his arm moves towards my gun. Left foot? Right? His trouser legs get fat above the camouflage boots. One is iced up, like a great big white earring. Target below, the end of his foot.

“What are you doing?”

“Million dollar wound. Hold still.”

“Wait!” He gets up.

“Let me put my foot on the stump.”

I let a breath out, glide the safety on. Then I switch it back.

“What?” I keep the gun up, but I look at him.

His face looks like it never had a smile. He points at me.

“I want to be the one to say I won't go.”

He pulls the silver dollar out, flips it, catches it, repeats. I watch it turn in the air between us. I expect my dad to appear, to snatch it.

His scream comes from somewhere so deep there's no voice to it. From the air itself. I can't look at his foot, to see if I maimed him.

The impact blew it off the stump and the stump is between me and it. Blood coats the jagged top. Some splinters are siren red, blasted back. The snow looks like somebody flung red paint from a brush. He's screaming, trying to breathe so deep too, the scream gets broken into an echo. Arms crossed, he tries to get up from his waist, rolls from side to side on his shoulders, rocking. I throw myself across his arms and chest. He's swallowing his screams like a baby.

I work my way down his legs, still pinning him. Half his boot is blown away, the foot looks whole to the toes. Too much blood, but it isn't important.

I make a tourniquet, use my tracking arrow to wind it tight above the top of his boot. He's puking. I prop his head up; the silver dollar rolls into the puke on his chest, so I clean it in my mouth, then put it back between his chattering teeth.

When he bites, the muscles between his cheeks and jaws get rigid. Both legs twitch. The sun breaks the ridge beam of a barn roof a quarter mile away. The hawk is a feather in the clouds. I smell burning. I put his arms through the sleeves of my coat, tie the sleeves together. Better to drag him that way than to try to carry him.

At first the grain of the wheat stubbles defeats me, but I get him moving. The field is level but for a slight drain towards the barn. I walk backwards and pull him by the jacket. After fifty yards I collapse onto my knees.

“I need a gun. Lay still while I run back.”

He nods with his eyes open, full of dirt and hunks of straw.

I run. Heavy boots, stubble field. His gun is beside the stump and mine at the edge of the woods.

There's a blood trail along the impression of my dragging him through the snow. No big spots, but every few feet the snow is red on top, a circle the size of an apple. When I get back, I pant and gasp until I can keep my head up.

“Listen: I'm going to empty your gun towards the barn,” I warn him. “Maybe the old man will know something is wrong. Don't let it make you jump.” I untie the sleeves so he can move his arms.

I pump two quick ones off and they hit just below the barn. Three more, at the other corner. I wait to see if the farmer comes out. Five more, same place. Nothing. He wants to say something.

“Don't talk.”

A faded green pickup truck is at the curve of the road half a mile away. We look small out here, if the driver can even see us, over the slight hill. I tug to get going again. I turn around to walk forward, holding the coattail in the small of my back.

All at once it's easier. Then hard. Then easier. I look around. He's raising his good knee to push his heel into the ground. We go on like that, him half-stepping to help when he can. My arm muscles begin to throb and I have to stop. I pant, he pants.

The farmer looks like a child, so far away at the corner of the barn. I drop the sling, wave my arms over my head, yell, then scream. He takes a few steps with his cane, away from us, and disappears behind the barn again.

I start shaking, my whole body like a paint mixer. I clench my arms at my waist and squeeze, but my breath only comes in short bursts. I feel faint.

The tourniquet has stopped the bleeding but turned his foot white. The blood vessels at his ankle bone are as big as a pencil, blue rivers on a white map. Two toes are gone. A perfect shot.

“Sthee muh foot,” he burbles, and spits the coin loose, before he passes out.

I want to rest, but he's lost a lot of blood by now. He'll limp.Wear a special shoe, have to explain over and over, live a lie. When I start again I feel him push us along too, a jerky thrust that becomes part of our slow movement. The old man shows again and raises his cane in the air.

“Help! Goddamn it, help! I shot him!” I try to run towards the barn, but I can't.

The farmer's vanished. It's windy and a lot colder now. No shadow, one star on its way down, over a dead tree with a tire swing tied to a low limb, next to the house. I round the corner. He's leaning against the wall with one hand, and on his cane. For a minute it feels like I am here to help him.

“I tripped. Fell.” I lie, “and the slug went through his foot. He's bleeding bad. Where's your phone?” He looks like I'm about to attack him. He doesn't understand.

“Man, my boy's hurt!”

“Eh?”

This morning he heard all right. He looks far off, but we're two feet from each other. The nearest hospital is forty miles away, but they have a helicopter. Just the end of his foot. He's okay. I put my hands below his old chin and look deep into his eyes.

“He is… hurt.”

Somebody was shooting at me,” he says all at once, “Ten times.”

I recognize the thousand-meter stare.

“That was me. Ten shots into the little hill where your barn drops off. Can you hear me?”

“Yup.”

Inside, he wants to sit down.

“No. Where's your phone?”

“Don't work. Girl brought me one last week from charity. Dinky little fucker, no cord.”

“Where is it?”

One of the cats comes through the door and lands on his lap like a balloon. I squat in front of him, shake his knee a little. His clothes stink. The cat's dandelion eyes watch me. He says the phone is on the table so when I go inside I'm looking for a table. The cupboard doors are all open and the counter is covered by stacks of sacks and cans of food, light bulbs, old jackets. The faucet is dripping into a broken bowl in the gray sink.

The next room is where he lives. A big dirty window with basketball-sized spots where he wipes a hole through the grime. Another barn chair's against the wall, the phone beside it. I go outside and dial 9-1-1. A woman, clear voice, answers. She tells me to slow down, tell her about it.

“Hunting accident. Not hurt bad, but bleeding pretty good. He's in a field. I can't drive to him.”

Other voices in the background. The phone reflects my breath. She's typing something. The old man limps to the door, watches me pace in little circles. The hawk flies high, big circles, over where Seth would be.

He is sitting up when I get back, turned around from how I left him, shivering. The bloody sock is lying on his other leg. The foot is mutilated: white again, the dried blood on his pants leg a black knot. I faint. Come to right away, and I hear a helicopter far off. It's a forty-year-old sound; I always hear them before anybody else.

“What's wrong, Gramps? You having a heart attack?”

“I'm okay. You weak?”

The helicopter's a moving speck.

“That's your bird, Seth. They're coming to get you. What happened to your foot?”

For an instant he's confused.

“I was tying my boot and you tripped. Your gun went off.”

He lies back and I clean his face. The dollar is on the trail. The helicopter lands about fifty yards away and a man carrying a suitcase gets out. A blonde woman follows him, with a black stretcher, folded in half. The bird throttles down and the blades stop. When I stand up Seth pulls on my pants leg.

“Thanks,” he says.

She holds his ankle and the guy wraps the foot, then they put it in a brown Velcro bag, load him onto the stretcher.

“I'm going to get his mother. We'll be at the hospital in an hour.”

They both look at me like I'm stupid.

While they're dressing his foot, I go back for the dollar and when I put it between his teeth the medics look at each other. The jet engine takes a big breath out of the field, there is a high whine, a beautiful sound, and they lift off, swoop immediately and are gone, soon a throbbing spot headed towards the distant amber clouds. The hawk, low over the wood is as big.

~ ~ ~

The town is small. I drive slow, looking for a phone, before I remember payphones are gone. I notice the inside of the windshield blue from cigarette smoke; the town sidewalks broken up like they haven't been repaired in fifty years; broken glass in an empty lot with three dead trees; heavy womp womp of speakers in cars that pass; smell from a gray factory, like burned toast, hanging in the street.

At a drug store a skinny girl tells me there's a phone at the fire station two blocks away, hanging on a rough brick wall. There's a carload of kids at the edge of the parking lot. Our number rings four times.

“Mary?”

“Daddy? What's wrong?”

“Listen ….” My mouth is full of the bottom of my throat.

“Why did you call? Where's Seth?”

“He's in the hospital. I tripped…my gun went off. It got him in the foot. He's not bad Mary, not bad.”

I expect her to be hysterical but she sounds calm. I can see her leaning against the wall.

“How are you? Are you all right?”

“I'm okay. I'll come get you and we'll go to the hospital.”

~ ~ ~

She is small, good-looking enough to turn heads in the hospital lobby when Mary walks ahead to the information desk. Veteran's hospitals are always full of men waiting. For appointments, prescriptions, test results, a ride, a woman like Mary to walk through. Waiting is a habit bred in the military. I stand behind her looking at everybody else.

“He's in surgery, we have to wait here,” she says.

“He'll be okay.”

“Daddy, why were you walking with your gun loaded?” Her hazel eyes roam around my face.

“It's a habit, honey. Something I brought back with me.” It's all true.

“He was supposed to leave next week.”

A stocky man comes out a door behind her and calls a number. Then a guy in a wheelchair that squeaks raises his hand and rolls by us. Two short legs, no knees, pants legs pinned shut, draped over the chair's arms. He's young. The stocky guy greets him and rolls him through the doorway. I hear the chair squeaking until the door shuts itself, then I hear the breathing of the guy sitting beside me. He's asleep and smells like booze. Mary rests one elbow on her leg and holds her head with that hand, holds my hand with her other one. Her hand is tiny. She wraps it around three of my fingers, rubs them with her thumb.

I don't know what I've gotten us into, or out of… He'll be okay. Maybe not play basketball, but even amputees play, on fake legs. Special shoes. He'll get used to lying about it.

The guy beside me is sleeping, boozy breath. He pisses me off, but I envy him.

Mary's grip loosens and she leans against my shoulder. I kiss the top of her head and clench my fists to stifle a sob. I'm going nuts, right here.

He's awake, doped up, face white. I expected the foot to be wrapped in thick bandages, not just looking like it's taped up for a sprained ankle.

Mary takes his hand and kneels beside the bed.

“Daddy told me how it happened.”

She says it like I'm not here. He glances my way, but I can't tell anything by his look. He stares for a long time at his mom. Like there's a secret between them. Some smell in this white room reminds me of my own stink. On my way down the hall I begin to wonder what they'll say while I'm gone.

Mary and I sit in the black chairs. Seth sleeps. I wonder if he dreams about it. There's guilt from being close to something big, and there's more guilt from being in the middle of it. Maybe I'll never be able to die, now. I am scared of being an old man scared of living with himself.

Usually, Mary talks a lot, but she's silent now. Sitting with her ankles crossed, her elbow on her knee, chin in her small hand, she looks like she's studying the tile floor. It seems she knows something I don't, when it should be the other way around. She's wearing a necklace of ceramic butterflies and the way it swings from her neck, the butterflies are airborne.

I remember the Monarchs in the valley below us. Our LZ the highest point around. Four companies and Artillery; the mud turning into dust. It was morning. Migrating through the jungle, as if a truce had come, were thousands, hundreds of thousands, tiny agents: orange and black flags, flying across us, through us, everywhere. The fluttering, noisy, cloud of them draped all the way to the valley floor. Everything seemed to stop. So quiet we could hear their wings paw through the mountain dust. Sound like feather-plucked guitar strings.

Two seats away is a guy with a huge Adam's apple and gun-barrel blue eyes like two line drives. His face should be on a calendar; he's too young-looking to be on Uncle-Sam-Wants-You posters, but the face is too honed to go to waste. He isn't looking right at me, but rather out the window behind me, and for a minute I can't look anywhere but into his eyes. I think of line drives. Say, when the mosquitoes are in off the river, towards the end of a pickup game, sunlight winking through the shabby bleachers behind third base, and a THWACK! Busts the ball out of nowhere, right at me… well, the guy's eyes are like two of them.

Of course I'm trying hard to think of something, anything besides this jet that is as big as a barnyard. I wonder where we are. From Seattle to Wake Island, where I only barely woke because me and some little guy sneaked a bottle of bourbon through the fence at Ft. Lewis.

The goddamn U.S. Army locks you in a fence twenty-four hours before your flight.

Twenty bucks for the bottle, but it kept me passed out until the rough landing scared me awake. That was when I first felt this alone. So alone, even though the plane is crammed full of guys like me. Like a toy box full of play soldiers.

Now, the plane's wing points steadily at a splotch of rock in the ocean while we spiral lower. My seat belt is too tight, I need to piss. The guy beside me wakes up and soon everything is almost upside down.

~ ~ ~

“FALL OUT!”

Some prick lieutenant screams it like his echo is the only thing he's ever heard. So Okinawa is another airport, another stepping stone toward The Whore's door.

“Ungoddamnly hot here. I'd rather be home,” from the guy with those eyes.

He moves his mouth a lot when he talks and his whole face changes but it starts and stops in that calendar smile. His voice moves that Adam's apple moves like a busy bobber on the end of a fishing line.

Some lifer directs us to a painted yellow line while he is talking. “This here shit-lookin’ rock is Ok-i-fucki-Nowhere,” he says.

Ok-i-fucki-Nowhere is scorching concrete checkered by red and yellow lines. The front wheels of our plane are straddle a red one. Our yellow line stretches forever west, unless the sun sets differently in Asia.

We are jungle-green mockingbirds and, like he's holding a cracker, there's a guy facing our line who reads the roll-call numbers through his nose:

“US five-five, niner-four, niner-seven, one, one.”

“Here,” one bird calls.

“RA three fifteen, forty-six, sixty-six oh seven,” like he's pinching his nostril.

“Here.”

Standing in that heat, completely Olive Drab, we don't seem like men—instead like poultry, like a truckload of doomed fryer hens, all so alike.

“I'm Albert Steven Saxon, answer to Ass, hail from Kansas City, and I'd rather be there instead of here,” he says.

His speech is fast and even, like baseball chatter. He pops little bubbles out of his chewing gum when he isn't talking. It seems like his jaw muscles would get sore.

“I'm Gabriel Sauers, from near Cincinnati.”

Our line lumbers toward the tropical webbing that pushes against the airport concrete. There are vines as thick as telephone poles that wind through each other and into some stubby trees that don't have tops. Above the trees is the looming tower of the terminal, studying the landing field like it a one-eyed rooster.

A path that is almost invisible from the runway leads to an open area where a lot more guys are sitting in red dust. No one seems to have anything to do. Some are smoking or reading, but they are mostly grouped into fours and fives, sitting in the dust, probably talking about yesterday or a year ago.

Albert Steven Saxon sprawls into the dust and pulls his hat over his eyes. He is lanky. His legs look like they grew twice as fast as the rest of his body, and his uniform fits funny. The shirt bags out like it is full of air and his pants are about the right length but shaped like sausages.

“How long you reckon we'll be laying around this here hole?” he asks.

“Not long enough. The next stop is the big one, I'm sure of that.”

“‘The big one.’” I like that, Gabriel,” he tells me, from underneath his hat. He says it again, and the bill of his Army baseball hat is so low all I can see is that calendar smile, teeth like a tight white fence.

Another plane comes in, a military transport, camouflaged in the same colors as the jungle that this airport is hacked from. But I'm not ready for the load of guys that streams out: not in any line.

Marines. Fuckin’-A filthy. Pimples galore, jags of beard, in ODs that are torn and stretched and not even olive drab but permanently rusted-looking, red, the color of the dust. The first ones that come into the clearing pass the word back to the others still on the airfield.

“Hey,” one yells. “Get a load of these newbie dudes!”

And as they come in with their enormous packs, every single one stands a minute and eyeballs us. They are ragged, they stink, there is almost no difference between the color of their jungle utilities and their faces. They are carrying rucksacks that are like mule packs: dirty, bulging sacks with things tied on by shoelaces; bandoliers of machine-gun ammo are strung around some like vines. They've got every weapon I've ever seen: mostly rifles, M-16s that are gouged and broken, some held together by tape. There are M-60 machine guns and a few shotguns. Almost all of them have grenades tied to their rucks, and everyone who has a hat on wears a “boonie” hat, camouflaged jobs, like duck hunters wear.

“Jesus.” Ass comes off his back and pushes his Army Issue baseball hat back, then just sits there, eyes line-driving the other guys. A short Marine comes over our way and stands staring back at Ass, who is staring only because he can't help it. The Marine asks if anybody is from the City, and the guy next to us answers Oklahoma City.

“Oh, Jesus. A bunch O’ dumb-fucker clodhoppers.”

The first few minutes of conversation are like that. We are foreign and antagonistic to each other. As more Marines come and spread throughout the clearing the conversations change. One guy wants to know who is leading the American League and if the ‘69 Chevies will really come stock with FM radios.

“Where'd ya get those hats?” Ass asks eventually.

“Quang Tri. We're up near the Z. They sell ‘em everywhere. You'd best get one if you go to the field.”

He takes his hat off and gives it to us. It has been rolled, crammed, and wadded so often it doesn't have a shape. Like a shrunken gunnysack. The whole thing is covered with inkings that are fuzzy because they've been wet and been gone over a lot of times. It has a calendar with days X'd off and the names of places he has been. “God is my point man” is written in red ink.

“Keep your pot close by, though,” he says. “You'll want to crawl up inside that fucker sometimes.” He slaps his steel helmet, which hangs on the bottom of his rucksack like a mushroom broken off its stem. He lights a cigarette with matches and uses only one hand.

“Been in the field for seven months and been getting the shit kicked out of us for a solid week so they lifted us out, too many guys losing it, know what I mean?”

“Guys going crazy, huh?”

“Going, goinger, and gone—that's all there is left of us. I flipped my own damn self, couldn't have taken another day. Fuckin’-A lost it.”

I wish afterward that I didn't notice his eyes that get like clear shooting marbles in the handsome red face.

~ ~ ~

There is something so common to all of them. Things hang around their necks: dog tags taped together so not to rattle, rosaries, three and four strands of beads, silver crosses, crude peace medals. There is no extra flesh on the hundred of them. They are all, in fact, as skinny as Bluetick puppies.

And they're all high or getting that way. One guy pulls out a bag of dope that is as big as a softball and rolls a joint eight inches long out of C-ration toilet paper, and when I get a hit I know it ain't like any dope I've ever had.

On two hits I get ungodly high. I keep flashing between these veterans and squirrel hunting back home. Today is opening day. These guys and their plastic rifles don't have much in common with the old farmers waiting in the woods for daylight, but as I lie there too stoned to move I daydream and the feelings seem a lot alike. Bullets are the only thing hunting and war have in common, but I want to find other things, to calm myself.

~ ~ ~

For twenty-four hours the war machine breaks down somehow, somewhere. The Marines can't leave until something changes, and we are held up by something else. Little by little we mingle with the vets, but there is a constant gap of experience that keeps hold of the conversations, the feelings, the looks, even the laughs.

I keep comparing the differences in their hats and ours. Ours are all alike: olive-drab Army baseball hats. The tags inside all read “Cap, man's cotton, OC 107 DSA 100-65,” but all their Boonies read differently:

Fuck the Army.Try a little tenderness.War is hell and scary.West by God Virginia.Stop ugly children, sterilize LBJ.

I spend the whole night in about the exact spot where I first sat down. The air hardly changes temperature, and when I wake up in the middle of the night the sky glitters. Ass is sleeping beside me, and the sounds he makes are like practice snores, as if the voice he snores through hasn't deepened yet. On the other side of the clearing I can see a flashlight moving and a guy is calling, “Hawkins, Cecil Hawkins,” in a singsong way, over and over. After I get up and take my leak and get back down I don't think I'll be able to go to sleep again, but the last thing I remember is that voice singing for Cecil Hawkins, nearer but still far away.

It is just getting light when they line us into the plane alphabetically. Saxon, Albert S., draws the seat across the aisle from mine. He is making conversation with the guy next to him while the plane is taxiing.

“Well, y'reckon the war will be over by tomorrow?” he asks me after we level off.

“I doubt it. Last I heard they couldn't decide what shape to make the peace table.”

I try to read but I can't concentrate. When I give up the book we are going through clouds the color of Mom's hair.

When we begin to drop he says, “Here we go,” so when we land

I say, “Here we are.”

Cam Ranh Bay doesn't look anything like I imagined it. And I had imagined it, imagined it, imagined it.

When we were making our low approach, the village itself looked like stacks of wood chips.

We get processed through the airport and put into a bus. The compound is centered around the airport. There is nothing but buses, jeeps, and trucks on the roads. For one short distance we cross through gates and drive for five minutes through sand dunes. All along the road is concertina wire laid in three layers with guard towers every so often. There are Vietnamese walking along the road. There is a scrapped tank swarming with little naked kids. Everything seems extra noisy—the high whine of the bus's diesel engine, planes landing and taking off over the road, helicopters hovering in lines.

I can see the village now and then through the sand hills. It is very low to the ground. Nothing sticks up higher than ten feet. When we approach another part of the compound the road is flanked by sandbagged watchtowers. Men hang out of some of them as we go slower now. They yell.

“God pity Eleven Bravos.”

“I'll be eating your sister's sandwich in twenty days.”

“Peace, brother.”

No one in the bus yells back. Eventually we stop and line into lines that line into ranks that line-drive into a mess hall, eat in twenty minutes, and line again in front of a staff sergeant.

“Men, welcome to Vietnam.”

The NCO is young but wrinkled and squints into the sun behind us. He goes on in a monotone that must have been saying the same thing for a year.

“Since there are almost no VC left around here you will not be issued weapons until you get ready to go to your units. Anybody who doesn't have his dog tags go to the line over there. You must have two dog tags all the time in Vietnam. If you get blown away, somebody will shove a tag between your teeth and kick your jaw shut, so we don't ship the wrong bag of guts to your mama. Any questions?”

I think at a million miles an hour while we go from station to station: to be positive we all have two dog tags, to be given ration cards, to have explained for the tenth time why U.S. forces are in Vietnam. We get told to buy savings bonds, warned about Hanoi Hannah—“the blackest clap of ‘em all”—taken to a sandbagged chapel where the chaplain is drunk, then issued a steel pot and five pair of green underwear. Mine are big enough to fit a rain barrel.

On our way to the mess hall we have to get pneumatic shots.

A tobacco-spitting medic who tells the guy in front of me he was a garbage truck driver on the Outside hits my vein, and the blood runs down to my elbow and drops onto my pants. The medic waiting to shoot my other arm says, “Let it drip and put in for a Purple Heart.”

~ ~ ~

Everybody is tired and grouchy and there is shouting in the barracks after supper. There is a two-man outdoor shower, and the line moves fast because everybody in line hustles the guys under the water. I'm a little surprised that the water is lukewarm. It comes from a big tank that gets heated by the sun.

The barracks are stuffy, and after I claim a bunk below Ass I go outside to have a smoke. Ours is the last one in a row, and the distance between the barracks and the perimeter of the compound is only two hundred meters.

The airfield is toward the center of camp. Over the roofs of the barracks buildings are at least twenty helicopters heading different directions, blinking green lights. Almost all the sound I hear comes from the helicopters: sometimes I distinctly hear the whoosh of their jet motors, but mostly there is the out-of-cadence whap-wop-wop-wop-whap-whack from the blades chopping air at different angles. The birds have red and green lights but only the green lights blink, and watching them from this distance is like seeing a pinball machine working through an arcade window. All at once I am conscious of a guy standing beside me, and I get the feeling he is watching the exact green lights that I am.

“Howdy,” he says; then, before I can answer, “You're new, huh?” His voice is higher than I expect. He is a pretty big dude.

“Been here almost a day.”

He lights a smoke in one quick motion, and when I smell it I know it's dope.

“With luck you've only got three hundred and sixty-four more.

“I got one.”

He whistles the smoke out and hands me a joint.

“What's it like to make it?”

“I didn't make it whole,” he says. Now I see his arm is bandaged and strapped to his side.

“How bad, uh … ?”

“Coulda been my nuts,” he says. “I've got all my hand left.

“Good,” I mean to fill the silence.

“One finger.”

The quietness gets clumsy. Next thing I know I ask him how it happened. The dope is making me talk.

“On an ambush. A noise, and some Effengee panicked and laid a round my way. Simple.”

“Effengee?”

“F, period. N, period. G, period. Effengee. Fuckin’ New Guy. They're all alike. You're one. You'll see. I'm Lonesome.”

“Me too, and I just got here.”

“Lonesome's my nickname. I got it because I built one-man hooches when I was in the field.” He stands up. “I'm done here. Goin’ home, can you dig that? One more day of that fuckin’ hospital and I get on my freedom bird. In a hundred hours I won't be Lonesome. I'll be Chester again …. Or maybe I'll get a new nickname, maybe Unfinger. I'm going shopping in the village, wanna come? Ten bucks for a pipe of opium and a blow job.”

“Thanks, man, but I just got here.”

“And you might get your shit blown backwards tomorrow. Think about it.”

~ ~ ~

Halfway across the open area he takes his hat off and gives it to me. The back of his head is shaved and bandaged, but I don't ask him anything about it.

“You got to get rid of that Effengee baseball hat as soon as you can. Get a Boonie, first time you go to a PX. In the field it's like a woman, can you dig that? I mean, it's something the Army doesn't give you. They give you a number and everybody else a number. But the hat is yours and you can paint it pink if you're nuts enough. Putting your name on it is enough. Like a zero—the Army doesn't like zeros. The reason I gave you mine to use is so not everybody can tell at a glance you're an Effengee, can you—”

“Dig it,” I say. I can see him smile in the light from the bunker line. Our side of the perimeter is dark, but the outside is lit up by huge spotlights mounted on top of the guard towers.

He stops us in back of Bunker 23 and hollers, “Three times twenty-three is sixty-nine.”

A flashlight shines from the window and a voice comes from where it goes out. “Wanna get the clap, eh, Lonesome?”

“I got the Jones, man. Gotta get one more crossmounted pussy before I'm a gone muthafucker tomorrow at noon, buddy.” He says “gone” especially loud.

“What's in it for us, my man?”

“Best they got.”

“Wait one.” And the spotlight on the bunker goes out. Lonesome shows me how to get through a break in the concertina wire, and we are soon galloping down a wide path beyond the range of the spotlights. Another, smaller, trail leads through some vegetation for maybe fifty meters and suddenly to a hut. The hut is lit by a candle sitting in the middle of the dirt floor. A small woman with black teeth is sitting beside the candle smoking what looks like a cigar rolled out of yellow leaves. She is wearing black pajamas and rubber sandals made from used tires.

“Mamasan,” Lonesome says, “We want opium and a blow job, one at a time.”

“Only one baby-san,” she says.

He goes into the corner and lies down on a pile of brown rags.

Mamasan motions to me to sit down and pulls a rag from out of her pajamas, which are thin and full of rips. A girl who can't be over four feet tall comes in and goes to Lonesome. She doesn't say anything. She begins playing with Lonesome, and when she kneels down I see that she only has half her right arm.

The woman looks like a squirrel. Her face is small and round and her black teeth move nervously like a squirrel's. She opens the rag on the floor beside the candle, and there is a small pipe with a long stem and a small bottle of brown liquid. She lights a piece of straw to warm the pipe, then hands it to me and fires it while I drag—just one quick sensation that makes me think of swallowing a spark. The woman sticks the tip of her brown tongue into the bowl of the pipe, then props it between her feet to refill it with one more drop.

The first rush comes and it feels like a part of my head inside is soft and woven, airy, like I've got a sock cap between my brain and my skull. The edges of everything fade too, like wearing sunglasses at night. The woman looks even more like a squirrel, and when she brings the pipe to my mouth the way she holds her arms is the way a squirrel holds a nut.

After that hit she and Lonesome help me onto the pile of rags and I just lie there and cruise. Another GI comes to the door and Mamasan goes outside to talk to him. Lonesome is sitting by the candle with his pants rolled up to his knees, scratching. His legs are raw and he opens scabs as he scratches. His feet and ankles are black.