Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

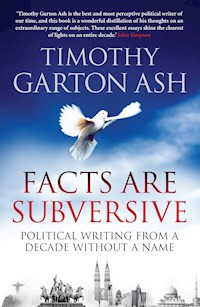

'Timothy Garton Ash holds a mirror that magnifies... He writes masterfully and with compassion' - Neal Ascherson, Observer For more than thirty years, Timothy Garton Ash has traveled among truth tellers and political charlatans to record, with scalpel-sharp precision, what he has found. Facts are Subversive, which collects his writings since the millennium, addresses some of the crucial questions of our time: what happens to people who have endured long dictatorships when they try to found a democratic state? How can freedom from tyranny be won? How are free expression, equality before the law and equal rights for men and women sustained in a society of different faiths and ethnicities? This is history of the present on a scale by turns panoramic and human: urgent, exhilarating and necessary.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 686

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FACTS ARE SUBVERSIVE

Timothy Garton Ash is the author of eight previous books of political writing or ‘history of the present’. They include The Magic Lantern, The File, History of the Present and Free World. He is Professor of European Studies and Isaiah Berlin Professorial Fellow at St Antony’s College, Oxford, and a Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. His essays appear regularly in the New York Review of Books and his weekly column for the Guardian is widely syndicated in Europe, Asia and the Americas. He has received many awards for his writing, including the Somerset Maugham Award and the George Orwell Prize.

www.timothygartonash.com

First published in hardback and export trade paperback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Timothy Garton Ash, 2009

The moral right of Timothy Garton Ash to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The author and publisher would gratefully like to acknowledge the following for permission to quote from copyrighted material:

‘Poem without a Hero’, in The Complete Poems Of Anna Akhmatova by Anna Akhmatova, published by Canongate Books, reprinted by permission of Canongate Books; ‘Spain, 1937’, in Another Time by W. H. Auden, copyright © W. H. Auden, 1940, reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber for the author; ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’, in Collected Poems by W. H. Auden, copyright © W. H. Auden, 1939, reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber for the author; Manila Manifesto by James Fenton, copyright © James Fenton, 1989, by permission of United Agents Ltd (www.unitedagents.co.uk) on behalf of James Fenton; ‘You Who Wronged’, in New and Collected Poems 1931–2001 by Czesław Miłosz, published by Allen Lane (Penguin Press), 2001, copyright © Czesław Miłosz Royalties Inc., 1988, 1991, 1995, 2001, reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell, copyright © George Orwell, 1937, reprinted by permission of Bill Hamilton as the Literary Executor of the Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell and Secker & Warburg Ltd; Nineteen Eighty Four by George Orwell, copyright © George Orwell, 1949, reprinted by permission of Bill Hamilton as the Literary Executor of the Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell and Secker & Warburg Ltd; If This Is A Man by Primo Levi, published by Jonathan Cape, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd; Clay: Whereabouts Unknown by Craig Raine, copyright © Craig Raine, 1996, by permission of David Godwin Associates on behalf of Craig Raine.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 184887 091 8 eISBN: 978 085789 910 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Map

Preface

1. Velvet Revolutions, continued . . .

The Strange Toppling of Slobodan Milošević

‘The country summoned me’

Orange Revolution in Ukraine

The Revolution That Wasn’t

1968 and 1989

2. Europe and Other Headaches

Ghosts in the Machine

Is Britain European?

Are There Moral Foundations of European Power?

The Twins’ New Poland

Exchange of Empires

Why Britain is in Europe

Europe’s New Story

National Anthems

‘O Chink, where is thy Wall?’

The Perfect EU Member

3. Islam, Terror and Freedom

Is There a Good Terrorist?

La Alhambra

Islam in Europe

The Invisible Front Line

Against Taboos

Respect?

Secularism or Atheism?

No Ifs and No Buts

4. USA! USA!

Mr President

9/11

Anti-Europeanism in America

In Defence of the Fence

Zorba the Bush

The World’s Election

Warsaw, Missouri

Dancing with History

Liberalism

5. Beyond the West

Beauty and the Beast in Burma

Soldiers of the Hidden Imam

East Meets West

The Brotherhood against Pharaoh

Cities of No God

Beyond Race

6. Writers and Facts

The Brown Grass of Memory

The Stasi on Our Minds

Orwell in Our Time

Orwell’s List

Is ‘British Intellectual’ an Oxymoron?

‘Ich bin ein Berliner’

The Literature of Fact

7. Envoi

Elephant, Feet of Clay

Decivilization

The Mice in the Organ

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface

Facts are subversive. Subversive of the claims made by democratically elected leaders as well as dictators, by biographers and autobiographers, spies and heroes, torturers and post-modernists. Subversive of lies, half-truths, myths; of all those ‘easy speeches that comfort cruel men’.

If we had known the facts about Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction, or merely how thin the intelligence on them was, the British Parliament might not have voted to go to war in Iraq. Even the United States might have hesitated. The history of this decade could have been different. According to the official record of a top-level meeting with the prime minister at 10 Downing Street on 23 July 2002, the head of Britain’s secret intelligence service, identified only by his traditional moniker ‘C’, summarized ‘his recent talks in Washington’ thus: ‘Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy.’ The facts were being fixed.

The first job of the historian and of the journalist is to find facts. Not the only job, perhaps not the most important, but the first. Facts are the cobblestones from which we build roads of analysis, mosaic tiles that we fit together to compose pictures of past and present. There will be disagreement about where the road leads and what reality or truth is revealed by the mosaic picture. The facts themselves must be checked against all the available evidence. But some are round and hard – and the most powerful leaders in the world can trip over them. So can writers, dissidents and saints.

There have been worse times for facts. In the 1930s, faced with a massive totalitarian apparatus of organized lying, an individual German or Russian had fewer alternative sources of information than today’s Chinese or Iranian, with access to a computer and mobile phone. Farther back, even bigger lies were told and apparently believed. After the death in 1651 of the founding spiritual-political leader of Bhutan, his ministers pretended for no less than fifty-four years that the great Shabdrung was still alive, though on a silent retreat, and went on issuing orders in his name.

In our time, the sources of fact-fixing are mainly to be found at the frontier between politics and the media. Politicians have developed increasingly sophisticated methods to impose a dominant narrative through the media. In the work of spinmasters in London and Washington, and even more in that of Russia’s ‘political technologists’, the line between reality and virtual reality is systematically blurred. If enough of the people believe it enough of the time, you will stay in power. What else matters?

Simultaneously, the media are being transformed by new technologies of information and communications, and their commercial consequences. I work both in universities and in newspapers. In ten years’ time, universities will still be universities. Who knows what newspapers will be? For fact-seekers, this brings both risks and opportunities.

‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred’ is the most famous line of a legendary Guardian editor, C. P. Scott. In the news business today, that is varied to ‘Comment is free, but facts are expensive’. As the economics of newsgathering change, new revenue models are found for many areas of journalism – sports, business, entertainment, special interests of all kinds – but editors are still trying to work out how to sustain the expensive business of reporting foreign news and doing serious investigative journalism. In the meantime, the foreign bureaus of well-known newspapers are closing like office lights being switched off on a janitor’s night round.

On the bright side, video cameras, satellite as well as mobile phones, voice recorders and document scanners, combined with the technical ease of uploading their output to the world wide web, create new possibilities for recording, sharing and debating current history – not to mention archiving it for posterity. Imagine that we had digital video footage of the Battle of Austerlitz; a YouTube clip of Charles I being beheaded outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall (‘he nothing common did or mean / upon that memorable scene’ ... or did he?); mobile phone snaps of Abraham Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address; and, best of all, an audiovisual sampler of the lives of those so-called ‘ordinary’ people that history so often forgets. (Still almost entirely lost to history is the smell of different places and times, although that is a salient part of the experience when you are there.)

In Burma, one of the most closed and repressive states on earth, the peaceful protests of 2007, led by Buddhist monks, were revealed to the world through photos taken on mobile phones, texted to friends and uploaded to the web. American politicians can no longer get away with saying outrageous things on remote campaign platforms. As the Republican senator George Allen found to his cost, a single video clip posted on YouTube may terminate your presidential aspirations. (The clip showed him dismissing a coloured activist from a rival party as a ‘macacca’, hence the phrase ‘macacca moment’.) In the past, it took decades, if not centuries, before secret documents were revealed. Today, many can be found in facsimile on the world wide web within days, along with court and parliamentary hearings, transcripts of witness testimony, the original police report on the arrest of a drunken Mel Gibson, with the actor’s anti-semitic outburst documented in a Californian policeman’s laboured hand – and millions more.

Quantity is not always matched by quality. Behind the recording apparatus there is still an individual human being, pointing it this way or that. A camera’s viewpoint also expresses a point of view. Visual lying has become child’s play, now that any digital photo can be falsified at the tap of a keyboard, with a refinement of which Stalinist airbrushers could only dream. As we trawl the web, we have to be careful that what looks like a fact does not turn out to be a factoid. Distinguishing fact from factoid becomes more difficult when – as those foreign bureaus close down – you don’t have a trained reporter on the spot, checking out the story by well-tried methods. Yet, taken all in all, these are promising times for capturing the history of the present.

‘History of the present’ is a term coined by George Kennan to describe the mongrel craft that I have practised for thirty years, combining scholarship and journalism. Thus, for example, producing the essays in analytical reportage that form a significant part of this book is typically a three-stage process. In the initial research stage, I draw on the resources of two wonderful universities, Oxford and Stanford: their extraordinary libraries, specialists in every field, and students from every corner of the globe. So before I go anywhere, I have a sheaf of notes, annotated materials and introductions.

In a second stage, I travel to the place I wish to write about, be it Iran under the ayatollahs, Burma to meet Aung San Suu Kyi, Macedonia on the brink of civil war, Serbia for the fall of Slobodan Milošević, Ukraine during the Orange Revolution, or the breakaway para-state of Transnistria. For all the new technologies of record, there is still nothing to compare with being there. Usually I give a lecture or two, and learn from meetings with academic colleagues and students, but for much of the time I work very much like a reporter, observing and talking to all kinds of people from early morning to late at night. ‘Reporter’, sometimes deemed to be the lowest form of journalistic life, seems to me in truth the highest. It is a badge I would wear with pride.

To be there – in the very place, at the very time, with your notebook open – is an unattainable dream for most historians. If only the historian could be a reporter from the distant past. Imagine being able to see, hear, touch and smell things as they were in Paris in July 1789. If I have an advantage over the regular newspaper correspondents, whose work I greatly admire, it is that I may have more time to gather evidence on just one story or question. (Long-form magazine writers enjoy the same luxury.) In Serbia, for example, I was able to cross-examine numerous witnesses of the fall of Milošević, starting within a few hours of the denouement. During the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, I was a witness to the drama as it unfolded.

The final stage is reflection and writing, back in my Oxford or Stanford study: emotion recollected in tranquillity. I also discuss and refine my findings at the seminar table, and in exchanges with colleagues. Ideally, this whole process is iterative, with the cycle of research, reporting and reflection repeated several times. I have written more about this mongrel craft in the introduction to my last collection of essays, which was called History of the Present, and – in this volume – in an essay on ‘The Literature of Fact’.

Most of the longer pieces of analytical reportage that you find between these covers appeared first in the New York Review of Books, as did the review essays on writers such as Günter Grass, George Orwell and Isaiah Berlin. Several chapters began life as lectures, including my investigations of Britain’s convoluted relationship to Europe and of the (real or alleged) moral foundations of European power. Most of the shorter pieces were originally columns in the Guardian. I conceive these mini-essays as an English version of the journalistic genre known in central Europe as a feuilleton: a discursive, personal exploration of a theme, often light-spirited and spun around a single detail, like the piece of grit that turns oyster to pearl. Or so the feuilletonist fondly hopes.

Many of my regular weekly commentaries in the Guardian, by contrast, look to the future, urging readers, governments or international organizations to do something, or, especially in the case of governments, not to do something bad or stupid that they are currently doing or proposing to do. ‘We must ...’ or ‘they must not ...’ cry these columns, usually to no effect. Such op-ed pieces have their place, but suffer from built-in obsolescence. They are not reprinted here. Prediction and prescription are both recipes for the dustbin. Description and analysis may last a little longer.

Throughout, I argue from and for a position that I believe can accurately be described as liberal. Particularly in the United States, what is meant by that much abused word requires spelling out (see ‘Liberalism’). I write as a European who thinks that the European Union is the worst possible Europe – apart from all the other Europes that have been tried from time to time. And I write as an Englishman with a deep if often frustrated affection for our curious, mixed-up country, at once England and Britain.

The heart of my work remains in Europe. In this decade, however, I have gone beyond Europe to report from and analyse other parts of what we used to call the West, and especially the United States, where I now spend three months every year. And I have gone beyond the West, especially to some corners of what we too sweepingly call ‘Asia’ and ‘the Muslim world’. (The endpaper map plots essays on to places, taking some artistic licence around the edges.)

The biggest limitation for any historian of the present, by comparison with those of more distant periods, is not knowing the longer-term consequences of the events he or she describes. The texts that you read here have been lightly edited, mainly to remove irritating repetitions, as well as anachronisms like ‘yesterday’ or ‘last week’, and to harmonize spelling and style. I have also corrected a few errors of fact. (If any remain, please point them out.) Otherwise the essays are printed as they originally appeared, with the date of first publication at the end. You can thus see what we did not know at the time – and sit in judgement on my misjudgements. The most painful of these was about the Iraq war. As you will detect from ‘In Defence of the Fence’, I did not support the Iraq war, but nor did I oppose it forcefully from the start, as I should have. I gave too much credence to the fact-fixers at No. 10, and to Americans I respected, especially Colin Powell. I was wrong.

Since this is the third time I have collected my essays from a decade, let me add a word about the ten-year period from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2009. Decades are arbitrary divisions of time. Sometimes history chimes with them. Usually it does not. My first book of essays, The Uses of Adversity, chronicled central Europe in the 1980s. The 1980s ended with a glorious bang in 1989 – a moment when world history turned on events in central Europe. History of the Present chronicled the wider Europe in the 1990s, including some of the Balkan tragedies. 1999 was not a turning-point to compare with 1989, but it did see the introduction of the euro, the expansion of Nato to include three central European countries that had previously been behind the Iron Curtain, and what appeared to be the last of the Balkan wars, in Kosovo. The very fact that we were ‘entering a new millennium’ gave the sense – perhaps the illusion – of a historical caesura.

Unlike ‘the 1980s’ and ‘the 1990s’, this has been a decade without a name. I will not embarrass it with ‘the noughties’. That is not even a nice try. It is like strapping a frilly frock on to a sweating bull. Somehow it seems more fitting that this decade be left nameless, for not only its character but even its duration remains obscure. It did not begin when it began and it was over before it was over. After the long 1990s, we have the short whatever-we-call-them.

With benefit of hindsight, I would argue that the 1990s began on 9 November 1989 (the fall of the Berlin Wall, or 9/11 written European-style) and ended on 11 September 2001 (the fall of the Twin Towers, or 9/11 written American-style). With hindsight, the 1990s seem like an interregnum between one 9/11 and the other, between the end of the twentieth century in 1989 and the beginning of the twenty-first in 2001. If you look at my account of an extended conversation with president George W. Bush in May 2001 (‘Mr President’), you will see that the concerns of the most powerful man in the world were, at that point, quite different from what they would soon become. Islamist terrorists did not get a single look-in.

After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the Bush administration swiftly concluded – and Tony Blair agreed – that a new era had begun, one they defined as the ‘Global War on Terror’. The neoconservative writer Norman Podhoretz called it World War IV. But on the unforgettable night of 4 November 2008, which I was lucky enough to witness in Washington (see ‘Dancing with History’), as Barack Obama defeated John McCain to become the forty-fourth president of the United States, it turned out that this epoch was over almost before it had begun. Not that we did not still face a grave threat to our lives and liberties from Islamist terrorists – we did and we do – but because other dangers and challenges had emerged, or risen up the agenda. As a seasoned insider once observed: problems are usually not solved, they are just overtaken by other problems.

In this new ‘new era’, the rise of non-Western powers, especially China, the challenge of global warming, treated with such oil-fired contempt by the Bush administration, and what some saw as a general crisis of capitalism – or was it just of one version of capitalism? – all loomed larger. Meanwhile – but for how long? – the heartwarming phenomenon of Obamaism fed worldwide hopes. So that it looks as if this decade may actually have lasted little more than seven years, from 11 September 2001 to 4 November 2008.

Is this to overestimate the singular importance of the United States? Perhaps. Yet this was a period in which the policies of the United States changed the world as much as they had in any decade since the formative 1940s – but this time round, alas, mainly for the worse. What is more, I will venture a guess that, because of the rise of non-Western powers and America’s own self-inflicted financial plight (the two being connected, since Asian savings funded American profligacy), the United States will not be able to shape the next decade as it did this one.

As for Europe, our old continent has spent most of these nameless years failing to pull together in its dealings with an increasingly non-European world. It has therefore made less difference, for good or ill, than it did in the 1980s, when it was still the central theatre of a global cold war, or in the 1990s. Unless we Europeans wake up to the world we’re in, which we show few signs of doing, our influence will continue to dwindle in the years to come.

Yet these are just historically informed guesses, nothing more, and there is good hope that I shall be proved wrong. The kaleidoscope never stops turning. So I look forward to chronicling another decade, which we will presumably call the twenty-tens. Hindsight can wait until it is 2020.

TGA, Oxford, March 2009

1.

Velvet Revolutions, continued . . .

The Strange Toppling of Slobodan Milošević

On Thursday, 5 October 2000, as Serbs stormed the parliament in Belgrade, waving flags from its burning windows, and seized the headquarters of state television, which an opposition leader had once christened ‘TV Bastille’, it looked like a real, old-fashioned European revolution. The storming of the Winter Palace! The fall of the Bastille!

Now, surely, the last east European ruler to have remained in power continuously since the end of communism, the ‘butcher of the Balkans’, would go the way of all tyrants. There were fevered reports that three planes were carrying Slobodan Milošević and his family into exile. Or that he was holed up, Hitler-like, in his bunker. Would he be lynched? Or executed like Ceauşescu? Or commit suicide, as both his parents had done? ‘Save Serbia,’ the crowds were chanting, ‘kill yourself, Slobodan.’ Fired by images of revolution, and all the bloody associations of ‘the Balkans’, hundreds of journalists piled in for a grisly but telegenic denouement.

Instead, late on the evening of Friday, 6 October, Milošević appeared on another national television channel to make the kind of gracious speech conceding election defeat that one expects from an American president or a British prime minister. He had just received the information, he said, that Vojislav Koštunica had won the presidential election. (This from the man who had spent the last eleven days trying to deny exactly that, by electoral fraud, intimidation, and manipulation of the courts.) He thanked those who voted for him, but also those who did not. Now he planned ‘to spend more time with my family, especially my grandson Marko’. Then he hoped to rebuild his Socialist Party as a party of opposition. ‘I congratulate Mr Koštunica on his victory,’ he concluded, ‘and I wish all citizens of Yugoslavia every success in the next few years.’

Neatly dressed, as always, in suit, white shirt and tie, he stood stiffly beside the Yugoslav flag, with his hands crossed very low in front of him, like a schoolboy who had been caught cheating. Or like a penitent before the priest that his father once aspired to be. Sorry, father, I’ve cheated in the elections, ruined my country, caused immeasurable bloodshed and misery to our neighbours – but I’ll be a good boy now. It was incongruous, surreal, ridiculous in the pretence that this was just an ordinary, democratic change of leader.

Yet that is exactly what the new president also wanted to pretend. President Koštunica told me later that Milošević had telephoned him to ask if it was all right to make the broadcast, and he was delighted, because he wished to show everyone in Serbia that a peaceful, democratic transfer of power was possible. Earlier that same evening, Koštunica had appeared on the ‘liberated’ state television, suited and sober as ever, fielding phone-in questions from the public, and talking calmly about voting systems, as if this were the most normal thing in the world.

Yes, I found young people celebrating in front of the Parliament building that night, blowing whistles and dancing. But most of the friends I talked to – people who had been working against Milošević for years – expressed neither ecstasy nor anger, but a blend of wry delight and residual disbelief. Was he really finished?

That was nothing to the bemusement of the world’s journalists. Heck, wasn’t this supposed to be a revolution? But the revolution seemed to have started on Thursday night and stopped on Friday morning. No more heroic scenes. No bloodshed. The Serbs had failed to deliver. They had disappointed CNN, and ABC, and NBC. The Palestinians and Israelis were more obliging. They were killing each other. So half the camera crews left for Israel the next day. Those who stayed went on wrestling with the question: what is this?

A very odd mixture it was. On the same morning that President Koštunica moved into the echoing Federation Palace, just a few minutes before receiving the Russian foreign minister, one ‘Captain Dragan’, a legendary veteran of the Serb insurrection in Krajina, was marching into the Federal Customs building with a bunch of armed men and a Scorpion automatic under his arm. He was there to expel Mihalj Kertes, the Milošević henchman who controlled so many shady deals through the Customs. Captain Dragan told me Kertes was trembling, and begged abjectly for his life.

On Saturday, Koštunica had to stand around for hours in the shabby reception rooms of the 1970s-style Sava Centre, waiting for newly elected parliamentarians from the opposition and Milošević’s Socialist Party to resolve their wrangles and allow his formal, constitutional swearing-in. Meanwhile, a shock troop of the ‘red berets’, State Security special assault forces, including veterans of Serbian actions from Vukovar to Kosovo, was seizing the Interior Ministry. But they were doing this on behalf of the opposition to Milošević. Or at least, one part of it.

As the political parties met for coalition talks about a new federal government, self-appointed ‘Crisis Committees’ in factories and offices sacked their former bosses – in the name of the people. One minute I watched the paramilitary leader and radical nationalist Vojislav Šešelj denounce the revolution in a session of the Serbian Parliament. The next I was examining the pistol that Captain Dragan took from the hated Kertes. Lightweight, with a handsome, carved rosewood butt. Five soft-tipped bullets and one ordinary one.

Yet all the while, Milošević was quietly sitting in one of his villas in the leafy, hillside suburb of Dedinje, consulting with his old cronies. On my last day in Belgrade, I drove past these houses on Užićka Street, hidden behind high walls and security fences. Somehow I could not find a doorbell to ring.

1

What was this Serbian revolution? Obviously, much is still unclear about the Serbian events, which have inevitably been compared with the Polish ‘self-limiting revolution’ of 1980–81 and the central European velvet revolutions of 1989. My very preliminary reading is that what happened in Serbia was a uniquely complex combination of four ingredients: a more or less democratic election; a revolution of the new, velvet, self-limiting type; a brief revolutionary coup of an older kind; and a dash of old-fashioned Balkan conspiracy.

First, the election. What many outsiders failed to appreciate is that Milošević’s Serbia was never a totalitarian regime like Ceauşescu’s Romania. That is one major reason why his fall was also different. Yes, he was a war criminal, who caused horrible suffering to the Serbs’ neighbours in former Yugoslavia. But at home he was not a totalitarian dictator. Instead, his regime was a strange mixture of democracy and dictatorship: a demokratura.

There was always politics under Milošević, and it was multiparty politics. Even the regime had two parties: his own and his wife’s. Tensions between his post-communist Socialist Party of Serbia and her Yugoslav United Left contributed to the crumbling of his power base. But the opposition parties and politicians now coming to power, including Vojislav Koštunica, have also been involved in politics for a decade. True, there was police and secret police repression, up to and including political assassination. But there were also elections, which Milošević won.

They were not free and fair elections. The single most important pillar of his regime was the state television, which he used to sustain a nationalist siege mentality, especially among people in the country and small towns who had few other sources of information. That is why one of his earliest political opponents, Vuk Drašković, called it TV Bastille. But there were also embattled independent radio stations and privately owned newspapers. People could travel, say almost anything they liked, and demonstrate in the streets. Opposition parties could organize and campaign, and their representatives sat in parliaments and city councils. Another way Milošević stayed in power was to manoeuvre among them, to divide and rule. That same Drašković, for example, accepted power in the Belgrade city government – and, by all accounts, the accompanying sources of enrichment.

Money played a huge part in the politics of this poor and now deeply corrupted country. When I say money I mean huge wads of Deutschmarks stuffed into the pocket of a black leather jacket or carried out of the country in suitcases. The frontiers between politics, business and organized crime were completely dissolved. Milošević’s hated son, Marko, was a businessman and a gangster. Among many other properties, he owned a perfume shop in the centre of Belgrade called, appropriately enough, Skandal. On the night of Friday, 6 October, I stood with a crowd contemplating its charred and plundered ruins. He fled to Moscow, taking with him Milošević’s grandson, Marko.

The ruling family was at the heart of a larger family, in the mafia sense. Yet the godfather still preserved the outward constitutional forms and periodically sought confirmation in elections. He won them with the help of TV Bastille and a little quiet vote-rigging – but also because he could count on a divided opposition and a significant level of genuine popular support.

Only against this background can one understand why, in early July, Milošević decided to change the constitution and seek direct election for another term as president of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. We know now that this was a fatal mistake. Few thought so then.

Why did he lose the election he himself called for 24 September? The first and most unequivocally heartwarming part of the answer is: the mobilization of the other Serbia to defeat him. Against the collective demonization of ‘the Serbs’, after what ‘they’ did in Bosnia and Kosovo, one cannot say often and firmly enough that there was always this other Serbia. There are Serbs who have spoken, written, organized and worked against Milošević from the very outset. Their struggle was different from, but no less difficult or dangerous than, the struggle of dissidents under Soviet communism. Soviet dissidents risked imprisonment by the KGB. The Serbian dissidents risked being shot in a dark alley by an unknown assailant. They were not numerous, but they were always there.

One of them is Veran Matić, a thickset, black-bearded, phlegmatic man, always to be found in his office tapping away at a slimline laptop. With a dedicated team of journalists, and a lot of financial aid from the West, Matić built up an independent radio station, B92, which was seized by the authorities at the beginning of the Kosovo war – but continued to provide news on the Internet. He also developed a network called ANEM, supplying independent news and current affairs programmes to provincial radio and television stations not under Milošević’s control. Now, while TV Bastille denounced Koštunica and the opposition as NATO lackeys and CIA agents, this network calmly informed the country outside Belgrade about the true facts of the election campaign. There were also less well-known journalists who went to prison for printing what they thought to be true.

Vitally important was the student movement called Otpor, meaning ‘resistance’, founded in 1998 as a more radical successor to the student protests of 1996 and 1997. One activist told me that the Otpor members learned at seminars organized by Western-funded non-governmental organizations how rights campaigning and civil disobedience had been organized elsewhere, from Martin Luther King to last year in Croatia. These were students majoring in Comparative Revolution. But they added a hundred creative variations of their own. For example, they would appear in the long queues for sugar and oil with T-shirts saying ‘Everything in Serbia is OK’. Under their distinctive clenched-fist banner, they confronted the police again, and again, and again. More than 1,500 Otpor activists were arrested during the year leading up to the revolution.

Like civil society activists in the Slovakian elections that toppled Vladimir Mečiar in 1998, they organized a campaign to ‘rock the vote’. Popular rock-and-roll concerts were combined with the message to get out and vote. They dreamed up a slogan, ‘Vreme je!’ – ‘It’s time!’ or ‘Now’s the time!’ – which just happens to be exactly what the crowds chanted in Prague in 1989. Then they found an even better one, ‘Gotov je!’ – ‘He’s finished!’ That became the motto of this revolution, plastered on Milošević posters, written on caps and banners, scrawled as graffiti on city walls, and roared from 100,000 throats.

Many others in this world of independent activity – what in Slovakia they call ‘the third sector’ – contributed to the cause. Independent public opinion pollsters, some of them American-funded, did regular surveys that suggested Koštunica was winning. There were countless campaign volunteers and independent election monitors. Millions of Western dollars have been wasted in ‘civil society’ projects all over post-communist Europe, but this time, in this place, it was surely worth it.

Secondly, there was the fact that the very disparate opposition parties finally united. Not entirely, to be sure. The largest single opposition party, Vuk Drašković’s Serbian Renewal Movement, refused to join. Moreover, the Montenegrin president Milo Djukanović called for a boycott of the election, thus allowing Milošević to take virtually all the remaining Montenegrin vote. But still, eighteen parties got together in a Democratic Opposition of Serbia. Much the largest of them was the Democratic Party headed by the long-serving but also compromised and unpopular opposition leader, Zoran Djindjić.

The third reason Milošević lost was that Djindjić and others managed to subdue their own squabbling egos sufficiently to agree on the candidature of Vojislav Koštunica, the leader of the small Democratic Party of Serbia, which had split from the Democratic Party in the early 1990s. Koštunica was reluctant to stand – he self-mockingly says of himself that he was the first undecided voter – but the choice was perfect. For he had a unique combination of four qualities, being anti-communist, nationalist, uncorrupted and dull.

Koštunica never belonged to the Communist Party. A constitutional lawyer and political scientist, he wrote his 1970 doctoral thesis on the role of the opposition in a multiparty system. He subsequently translated The Federalist Papers and worked on Tocqueville and Locke. He was fired from Belgrade University for opposing Tito’s 1974 constitution as unfair to the Serbs. Unlike most other opposition leaders, he had never even met Milošević – until, on Friday, 6 October, the commander of the army, General Nebojsa Pavković, arranged a brief encounter between outgoing and incoming presidents. ‘So,’ Koštunica proudly told me, ‘I met him for the first time when he lost power.’

He was a moderate nationalist, who had supported the Serb Republic in Bosnia and fiercely criticized NATO’s war over Kosovo. Unlike Drašković or Djindjić, he had never been seen hobnobbing with Madeleine Albright. He had stayed in Belgrade throughout the bombing, whereas Djindjić had fled to Montenegro, fearing, perhaps rightly, for his life.

He was uncorrupt. I have rarely seen a more spartan party office than his. He lived in a small apartment with his wife and two cats, and drove a battered old Yugo car. Again, the contrast was acute with other opposition leaders, especially Djindjić and Drašković. With their smart suits and fast cars, they were widely believed to have their hands in the till – in the time-honoured fashion of most politicians in the post-Ottoman world.

His great disadvantage was thought to be his dullness. In the event, even this turned out to be an advantage. Again and again, people told me that they liked his slow, plodding, phlegmatic style. It was such a welcome contrast, they said, to all the heroic-tragic histrionics of Milošević, but also of many of his opponents, such as the ranting Vuk Drašković. ‘You know, I want a boring president,’ one leading independent journalist told me. ‘And I want to live in a boring country.’

And then, Koštunica wasn’t so dull after all. Energized – as who would not be? – by finding himself at the head of a crusade for his country’s liberation, he produced some brave and memorable moments. His ‘Good evening, liberated Serbia’, on the night that Parliament and television were stormed, will go straight into the history books.

Of course we can never know the exact compound of motives that made at least 2.4 million Serbs put a circle next to the name of Vojislav Koštunica on Sunday, 24 September. But two striking partial explanations were offered to me.

One concerns the NATO bombing. I asked politicians and analysts when they thought the revolution had begun. Several said, often through pursed lips: well, to be honest, at the end of the Kosovo war. During and immediately after the war, there was a patriotic rallying to the flag, from which Milošević also benefited. But it was too absurdly Orwellian to hear state television proclaiming as a victory what was obviously a historic defeat: the effective loss of Kosovo, Serbia’s Jerusalem. Economically, things got worse, and every demand to tighten the belt was justified by the effects of the bombing. The miners in the Kolubara coal mines, whose strike was to give a decisive push to the revolution, told me their wages had sunk after the war from an average of about DM150 a month to as low as DM70. The reduction was explained as a tax for post-war reconstruction. But it made them furious.

Then, as Veran Matić puts it, Milošević ‘fought the election not against us but against NATO’. Yet that didn’t work either, because at some deeper level people thought, ‘Well, he lost against NATO, didn’t he?’ If Matić is right, then Koštunica was an unconscious beneficiary of the bombing he deplored. This explanation is highly speculative, of course, and can never be proven. But it would not be the first time in history that war had helped to foment revolution.

The other partial explanation is less dramatic, but also convincing and important. It is that a great many people who in the past had voted for Milošević simply decided that enough was enough. The leader had lost touch with reality. Having been there so long, he was to blame for current miseries. It was time for a change. It was, says Ognjen Pribičević, a longtime Milošević critic, like what happened to Margaret Thatcher or Helmut Kohl, after their eleven or sixteen years of power. The comparison with Thatcher or Kohl may seem startling, even insulting. But it’s a useful reminder that for many Serbian voters Milošević was not a war criminal or a tyrant. He was just a national leader who did some good things and some bad things, but now had to go.

It was those people, finally, who brought the vote for Vojislav Koštunica just above the 50 per cent needed for him to be elected in the first round.

So that was the election. Already on the night of Sunday, 24 September, a sophisticated and independent election monitoring group – another part of the foreign-funded ‘third sector’ – told the opposition that Koštunica had won, and people danced in the streets of Belgrade until the early hours. But everyone knew that Milošević would not concede defeat. He would probably try to ‘steal the election’, fraudulently claiming extra votes from Montenegro and Kosovo. This was only the end of the beginning.

Sure enough, Milošević had the Federal Election Commission declare that Koštunica had won more votes than him, but not enough to secure victory in the first round. There would have to be a run-off second round on 8 October. The opposition now took a giant gamble, against the advice of many Western politicians and supporters. They said: no, we will not go to the second round. Instead, by orchestrating peaceful popular protest, they would force Milošević to concede that he had lost the election. And they set a deadline: 3pm on Thursday, 5 October.

The election campaign already had elements of revolutionary mobilization, like that of the Solidarity election campaign in Poland in the summer of 1989. Revelection, so to speak. But now things developed more clearly towards a new-style peaceful revolution. People came out on the streets of Belgrade and other towns for large demonstrations. The opposition knew that would not be enough. After all, in the winter of 1996–7 Milošević had survived three months of large demonstrations.1 So they called for a general strike. And they appealed to all the citizens of Serbia to come to Belgrade on Thursday, 5 October, for the demonstration to end all demonstrations.

The general strike was very patchy at first. But in one central place it took hold: in the great opencast coalfields of Kolubara, some thirty miles south of Belgrade, which provide the fuel to generate more than half of Serbia’s electricity. It was inevitably compared to the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk, birthplace of the Polish revolution in 1980. And to visit the Kolubara mines was indeed to be transported back to the mines and shipyards of Poland twenty years ago. The same plastic wood tables, potted plants, lace curtains, endless glasses of tea and folk music coming over an antiquated radio. The workers in blue overalls, with unshaven, grimy faces and rediscovered dignity.

As in Gdańsk, economic grievances helped trigger the strike, but the workers immediately subordinated their local and material demands to the national and political one. When the commander of the army, General Pavković, and the government minister accompanying him offered to double the miners’ wages if they went back to work, they insisted that they wanted just one thing: recognition of the election results. There was also solidarity, with a small ‘s’. On the night of 3–4 October, the number of strikers in the coalfields had dwindled and police moved in. So strike leaders called on people to come and support them. And they came in by the thousands, from the nearby town of Lazarevac, and from the capital. Outside one of the mines, the police stood in line, but irresolute. Finally, three old men on a tractor trundled towards them and the police line opened. A scene for a film – or a monument.

One should not exaggerate the similarities with Gdańsk; I could add a long list of differences. But the strike at Kolubara had great symbolic significance. It increased the revolutionary momentum and further broke down the barriers of fear. What followed was purely Serbian.

Early on the morning of Thursday, 5 October, great columns of cars and trucks set out from provincial towns, from Čačak and Užice, from Kragujevac and Valjevo, from the rich plains of the Vojvodina in the north and the Serbian heartland of Šumadija in the south. The convoy from Čačak, headed by its longtime opposition mayor, Velimir Ilić, had a bulldozer, an earthmover and heavy-duty trucks loaded with rocks, electric saws and, yes, guns. They literally bulldozed aside the police cars blocking the road. Other convoys also broke through police blockades, by a mixture of negotiation and muscle.

Many of those who came to Belgrade were ordinary people from opposition-controlled cities, sometimes better informed than their counterparts in the capital, because of the local independent television and radio stations, but often materially worse off than the Belgraders, and so more angry. However, among them were also former policemen and soldiers, veterans of the Serbian campaigns in Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo, tough, with shaved heads and guns under their leather jackets. Men who knew how to fight and were determined to win this day.

From north and south, east and west, they converged on Belgrade. They joined with the Belgraders who had come out in their hundreds of thousands, further infuriated by the latest absurd and provocative verdict of the constitutional court – which declared the presidential election null and void. So there they stood, massed with flags, and whistles, and banners reading ‘He’s finished’, in front of the impressive parliament building where the Federal Election Commission, which had falsified the election results, was also based.

It was three o’clock – deadline for the revolution. Then it was just past three, and someone in the crowd turned to Professor Žarko Korać, a member of the opposition leadership which had set the deadline, and said, ‘Well, Professor, it’s seven past . . .’

No one knew what would happen next. Or did they?

2

What happened between about three and seven o’clock on the afternoon of Thursday, 5 October, changed everything. Led by a man in a red shirt, defying police batons and tear gas, a crowd stormed the parliament. Soon thereafter, the nearby state television headquarters was trashed and set alight. A handful of other key media outlets, including the state television studio and transmission centre, and Veran Matić’s B92 radio, were more peacefully taken over. Koštunica cried, ‘Good evening, liberated Serbia’, to an ecstatic crowd, and they celebrated in the streets.

These events invite a moment’s reflection on the relationship between image and reality. Those who stormed the parliament created an unforgettable image of liberation – an image that CNN and the BBC sent around the world. This image then became reality. Taking over the state television was itself another compelling television image: the ‘TV Bastille’ in flames. But it also meant that the opposition now controlled the place that made the images. And that, not the army or police, is the very heart of power in modern politics.

I remember the Polish opposition leader Jacek Kuroń saying in Warsaw in 1989 that if he had to choose between controlling the secret police and television, he’d choose television. Our democracies are television democracies. (In the midst of the revolution, we paused to watch Al Gore and George W. Bush conduct one of the television debates that would decide a more normal presidential election.) Milošević’s dictatorship was a television dictatorship. And television was equally central to the revolution. From teledictatorship, via telerevolution, to teledemocracy.

This was a coup de théâtre that had the effect of a coup d’état. Who was responsible for it? I collected at least a dozen eyewitness accounts of the storming of the parliament, and they differ greatly. Success has many fathers. The ranks of those who did the heroic deed, or planned it, grow like relics of the true cross. About such events, the whole, exact and sober truth will never be known, but there is ample evidence that, beside much spontaneity, there was a strong com-ponent of deliberately planned, revolutionary seizure of power.

The mayor of Čačak, Velimir Ilić, described to me how he and his group prepared their trip to Belgrade as if it were a military operation. When I asked one of his vanguard, a burly former paratrooper from the elite 63rd Parachute Regiment, what the object of the operation was, he said crisply, ‘That Vojislav Koštunica should appear on state television at 7.30pm.’ Before they left, Ilić told them, ‘Today, we will be free or die.’

There is doubtless some retrospective self-glorification in these accounts, but other witnesses agree that the boys from Čačak were there in the front line, and well equipped to fight the police. A Belgrade friend who was there recalls a youth of fifteen or sixteen standing before the parliament and taunting the crowd: ‘Do you people from Belgrade need us from Čačak to show you how to take your own town hall?’ The provincial lad didn’t even know what the building was, but he was going to storm it anyway.

Čačak was not alone; there were many angry men from other provincial towns. When the first, heavy waves of tear gas were launched by the police, the intelligentsia of Belgrade mostly fled to nearby apartments, or offices, or cafés. Another friend met an acquaintance who said, ‘This is the biggest funeral ever.’ She thought the rising was defeated. But the hard men from the provinces came back into the square. They had no nearby apartments to go to, and they were here to finish the job.

The honour of Belgrade was saved by fans of the city’s leading soccer club, Red Star. They were, by all accounts, also fighting in the front line. They had practised already in their soccer stadium, taunting the police with their chants of ‘Save Serbia, kill yourself Slobodan.’ And they knew all about police tactics. Afterwards, the new mayor of Belgrade, the historian and opposition leader Milan St. Protić, thanked them for their heroic role. It must be the only time that a city mayor has thanked his football hooligans for going on the rampage.

Nor was it only Čačak that had made plans. Čačak’s mayor Ilić was a member of the coordinated national opposition leadership, and others in that leadership made their own preparations. Zoran Djindjić, the Democratic Party leader, and far more important than his modest title of ‘campaign manager’ for Koštunica would suggest, told me that he and his opposition colleagues had their own scheme to take parliament from behind – ‘but Čačak was too quick for us’. His right-hand man, Čedomir Jovanović, a charismatic former student leader, was on the spot, wearing a bulletproof vest. Another bulldozer was on the job at their request. And Captain Dragan insists that he received instructions from a close aide of Djindjić to seize the Studio B television station – which he duly did, escorting the security guards to safety past an angry crowd. Several opposition figures say they had their own sources inside the police, passing information to them on police tactics. Some time before 7pm, a commander was heard to say, over a captured police radio, ‘Give up, he’s finished.’

There are a hundred more pieces of the jigsaw to fit into place: retrospective claim and counterclaim about planned and spontaneous action. But the essential point is established. There was, after Serbia’s 1989 and its 1980, a brief moment of 1917: a deliberate yet limited use of revolutionary violence. It is hard to imagine the breakthrough coming without it. But the remarkable thing is how limited it was, and how quickly the country returned to new-style, peaceful revolution. Within a week, Otpor activists were organizing an action to encourage people to return the goods they had looted from the shops. One is tempted to say, although the phrase is a dangerous one – recalling as it does Auden’s notorious line about ‘the necessary murder’ – that they used the minimum of necessary violence.

The question remains why the army, and the powerful police and state security special forces built up under Milošević, did not intervene, instead leaving the ordinary police to throw some tear gas and then give up. For those forces, well equipped and battle-hardened, could easily have caused a bloodbath in central Belgrade – although it would probably only have precipitated a far bloodier end of the regime.

Here we enter the murkiest waters. Among the claims made about the army are that its chief, General Pavković, previously known as an arch ally of Milošević, refused to order his tanks to roll; or, rather more plausibly, that, on consulting with his senior commanders, Pavković discovered that they were not willing to risk using their largely conscript forces against their own people. (Reportedly, a clear majority of those who voted from the army and police on 24 September cast their ballot for Koštunica.) Zoran Djindjić told me that the feared ‘red berets’, formally the Special Operations Unit of the State Security Service under the Serbian Interior Ministry, received a direct order to bomb and retake the parliament and television. They did not carry out the order. Instead, two days later those same ‘red berets’, commanded by one General Milorad ‘Legion’ Ulemek (recognizable by the red rose tattooed on his neck), took over the Interior Ministry for – or, at least, in cahoots with – Djindjić.2

Belgrade being Belgrade, there are even darker speculations. For as long as I have been travelling here, people have been telling me fantastic tales about conspiracies – internal, but also Western, especially American ones. This is the world capital of conspiracy theories. But, in this case, I think there may just be some truth in them. The speculation is that disaffected former members of the army, secret police and special forces, who had earlier been wondering about trying to overthrow Milošević, now helped to ensure that he was misinformed and the forces unresponsive. In the case of the army, there is little secret. Two very senior former Milošević generals, Momčilo Perišić (dismissed as chief of staff in 1998) and Vuk Obradović, were now leaders of the opposition, and had publicly and privately appealed to their former comrades not to act against the people. But the most important figure mentioned is the former secret police chief Jovica Stanišić, who was fired by Milošević in 1998, but is still believed to wield much influence on those shadowy Belgrade frontiers where secret police, paramilitaries, businessmen, politicians and mafia-style gangsters intermingle.

The motives of such men in the shadows? First, ‘just to screw Milošević’, as the political analyst Bratislav Grubačić put it to me. Those that Milošević used and then cast aside were taking their revenge. Second, as a source once close to Milošević explained, ‘To save their lives. And their money – you know, a lot of money. Perhaps to keep their freedom too.’ And to try to make some accommodation with the new powers that be. Which, in this connection, seems to mean primarily Zoran Djindjić, about whom there are persistent rumours of earlier meetings with the former secret police chief. I was struck by the fact that when I asked Djindjić why there was not a popular march on the secret police headquarters, like the East German storming of the Stasi, he hastily replied, ‘No, we think there is valuable equipment there, which every state would need.’

This is all, I repeat, no more than informed speculation. To go further would require an investigation which I don’t intend to make. This was definitely not like Romania in 1989, where a group of people from inside the former regime organized a coup masquerading as a popular revolution. But Belgrade is a city where people do have the most curious connections. And something more than just the patriotic restraint of the armed forces, and the velvet power of peaceful popular protest, does seem to be required to explain the absence of any serious attempt at repression. If a little old-style Balkan conspiracy contributed to that outcome, well, three cheers for old-style Balkan conspiracy.

On that afternoon of Thursday, 5 October, one woman was crushed under the wheels of a truck. An old man died of a heart attack. The chief editor of state television and a number of policemen and demonstrators were beaten up. There are unconfirmed reports of two police deaths. That was about it. Little short of a miracle in a country still ostensibly ruled by Milošević, and stashed full of guns and men well accustomed to using them.

The combination of these four ingredients – an election drawing on prior multiparty politics, a new-style peaceful revolution, a brief revolutionary coup de théâtre and a dash of conspiracy – helps to clarify the puzzle that the world’s journalists encountered when they descended on Belgrade. So does the fact that different opposition leaders favoured different blends: Koštunica, the Girondin, always wanting to use peaceful, legal, constitutional means, demonstratively starting as he intends to go on; Djindjić, the Jacobin, more inclined to take direct action; while others were somewhere in between.

3

Four days after Serbia’s super-Thursday the opposition still only had in power, formally speaking, the president. ‘Yes, at the moment there is only me,’ Mr Koštunica wryly remarked, as we sat in the Federation Palace. He was the one figure in the land who was both legal and legitimate. A fortnight later the opposition had reached agreement with Milošević’s formerly ruling Socialist Party, and Vuk Drašković