Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Penned in the Margins

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

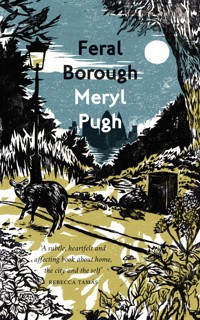

Set in the urban pastoral of an East London postcode, Feral Borough asks what it means to call a place home, and how best to share that home with its non-human inhabitants. Meryl Pugh reimagines the wild as 'feral', recording the fauna and flora of Leytonstone in prose as incisive as it is lyrical. Here, on the edge of the city, red kite and parakeets thrive alongside bluebell and yarrow, a muntjac deer is glimpsed in the undergrowth, and an escaped boa constrictor appears on the High Road. In this subtle, captivating book – part herbarium, part bestiary and part memoir – Pugh explores the effects of loss, and lockdown, on human well-being, conjuring the local urban environment as a site for healing and connection. 'A subtle, heartfelt and affecting book about home, the city and the self -- Pugh reminds us that nowhere, however urban, is without nature; that wherever we go, the intricate web of life continues to shape and change us.' Rebecca Tamás

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

MERYLPUGH

Meryl Pugh lives in East London and holds a PhD in Critical and Creative Writing from the University of East Anglia. She teaches creative writing, most recently as a lecturer at UEA. She is the author of three pamphlets and one collection of poetry. Natural Phenomena (2018) was a Poetry Book Society Guest Choice and longlisted for the Laurel Prize.

OLIVERBARRETT (ILLUSTRATOR)

Oliver Barrett is a musician and illustrator based in Somerset. He releases music under his own name, Petrels, Sun Do Silver, Glottalstop, Sphagnum Moss, and many more besides. His first, self-illustrated book, The Nuckelavee, was published by Tartaruga Press in 2015. You can see more of his work at floatinglimb.com

ALSO BY MERYL PUGH

POETRY

Relinquish (Arrowhead, 2007)

The Bridle (Salt Publishing, 2011)

Natural Phenomena (Penned in the Margins, 2018)

Wife of Osiris (Verve Poetry Press, 2021)

PUBLISHEDBYPENNEDINTHEMARGINS

Toynbee Studios, 28 Commercial Street, London E1 6AB

www.pennedinthemargins.co.uk

All rights reserved

© Meryl Pugh 2022

The right of Meryl Pugh to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Penned in the Margins.

First published in 2022

ePub ISBN

978-1-913850-13-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

Common Buzzard

Feral Pigeon

Artificial Tree

Pride of Leyton

Orange Bonnet

Domestic Shorthair Cat

Hawthorn

Skylark

Ash

White-cheeked Turaco

Hops

Nos

Common Wood Pigeon

Common Kestrel

Bittersweet

Blackthorn

Flasher

Common Field Grasshopper

Red Kite

Canalag Goose

Greylag Goose

Common Lime

Great Spotted Woodpecker

Common Black Ant

Honeysuckle

Loiterer

Muntjac Deer

Bluebell

Sweet Chestnut

Boa Constrictor

Ring-necked Parakeet

Lesser Redpoll

Swallow

Jersey Tiger Moth

White-flowered Honesty

Six-toed Cat

Common Wood Pigeon, again

Wren

Yarrow

SELECTWORKSCONSULTED

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In memory of

DONALDEDWARDPUGH

1940 – 2018

TARALOUISEFEW

1968 – 2013

§

and for Richard

Feral Borough

Common Buzzard

Buteo buteo

It is April and the neighbours’ children are playing in the garden. One of them has managed to turn on the sprinkler – much commotion as their mum admonishes Grandad, who is supposed to be supervising them. The children hoot with excitement while the sprinkler is turned off and a towel is fetched. The littlest one has learnt to say water.

A kerfuffle of pigeons, as if to mirror the human kerfuffle. Then a crow giving a half-strangled ‘kark’. I look up – and it’s harrying a – what? Bigger than the crow, brown, those big wings with the slightly blunt taper at the end – yes, maybe, is it? A buzzard, veering, jinking, dipping from the crow’s aim, crossing over to the Flats.

Later, I check on the London Birders’ Wiki page. There it is, recorded. Buteo buteo.

It is the end of June, a year after my buzzard sighting, and we are having another short run of fine days. England is in lockdown (SARS-CoV-2 made landfall a few months ago) and excited children’s voices draw me to the front room window. The neighbours and their kids are out in the street. The eldest child tiptoes to place a hand on a car window, while her mother carries her little brother on her hip. Their grandfather is in the car, all the windows closed, trying to make himself audible as he chats with his daughter. The little girl shouts to him and he aligns his hand with hers, the other side of the glass.

Without so much of the pollution haze, the sky seems a prism in which every one of its inhabitants is sharp against the blue. High up, in wide, slow circles, with hardly any wingbeats, the wings that look like butter knives twisted and damaged at the end or, no, like fish knives. A gull describes smaller circles, then veers and dips in attack threats that don’t impact.

The wide circling carries on. Beauty, oh beauty, oh.

Feral Pigeon

Columba livia domestica

It is May and very hot – unseasonal is the word that everyone uses. I am sitting beside a pond in a park near Waterloo, eating a sandwich before I teach my evening class. Feral pigeons are milling around, purring and bowing and puffing up their breast feathers at each other or stalking jerkily towards any remnants of dropped food. I stare at the water, wishing I was brave enough to dunk my feet. There is a clapping noise as the birds skirl into the air. One passes so close to me that I feel the small wind raised by its wings on my cheek. What happens next astounds me.

Pigeons are taking turns to fly into the pond, flapping furiously to hover above, then letting their bodies touch the surface of the water as they dip and ruffle first the head into the water, then the breast, then wings, before they rise with strong, fast wingbeats to land on the bank.

Then one actually settles on the water, like a duck. Its wings spread out in a wide spatula shape to help it float as it dips its head, wets its whole self. I have never seen anything like it before.

When I moved into this house – the one in which I’m writing this book – I didn’t pay much attention to its wildlife or landscape. In fact, wildlife and landscape both seemed redundant words for my new home and its surroundings. We moved here in the late nineties, leaving behind our flat in North West London to settle on the opposite side of the A-to-Z in Leytonstone. Housing was – for London – relatively cheap, the transport links were many and various, our workplaces half an hour away by Tube. The house was on a quiet, tree-lined road and had a small garden; we loved it the minute we saw it. But as for nature and wildlife? It didn’t have much of that. We were closer to the city, deeper in; there didn’t seem to be much room for the wild. I didn’t count the tree outside the house as ‘nature’ back then, nor the feral pigeons squatting outside the Tube station.

I was wrong, of course. As I got to know the area better, I realised that the constant noise from the motorway that cuts it in half, the congested local roads, the rows of terraced houses and blocks of flats; these are only part of the story. Shepherd’s purse between a lamppost and the tarmac. Herb robert between a shopfront and the pavement. Those feral pigeons. Foxes.

Leytonstone is part of the London Borough of Waltham Forest, one of the ‘new’ boroughs created in 1965, when Greater London’s boundaries were redrawn. Before this, it was considered a a subsidiary part of the Leyton district in the county of Essex. The name Leyton-atte-Stone originally designated a small number of dwellings that stood near a milestone on the eastbound road. In his history of the area, the wonderfully named W. G. Hammock notes that in 1584, ‘Leytonstone was then only a dependent hamlet’ of Leyton and quotes David John Morgan, a former Conservative MP for Walthamstow and Councillor for Leytonstone, who recalls that it was ‘one of the prettiest villages which could be imagined.’ In his younger days, Morgan would walk

... [f]rom the Church northwards ... passing what was then a field ... Mr. Payze’s farmyard, straw-littered, with its large black gate and black thatched barn, and then, beyond, a number of cottages with gardens which were always bright with flowers.

Then came the speculative building boom in the latter half of the nineteenth century and the village was swallowed up.

Poverty and wealth exist cheek-by-jowl in present-day Leytonstone, just as in the rest of London. Bookmakers and charity shops proliferate on the high street and one of the libraries has closed. A food bank operates out of the local church opposite a volunteer-run art gallery, while a nearby pub offers shabby chic sofas and boutique rooms upstairs. The views are of power pylons vaulting over to Ilford in one direction, and in another, above the roofs of Victorian and Edwardian terraces, the tower blocks that were once social housing. Past those, there is the punctuation of the buildings at Canary Wharf, The Shard and other nervy, twenty-first century attempts upon the London skyline.

Leytonstone is surrounded by a lot of green space, sitting as it does at the foot of Epping Forest’s insurgence into the city from Essex. Beyond the high street, there is a scrubbily untidy wood with an avenue of trees leading out of it towards a playing field. Further east, in Wanstead, there’s a park, formerly the grounds of a gentleman’s estate, where the ornamental ponds stink in summer and fill with bread crusts and drinks cans. They also sport kingfishers, herons, gulls, tufted ducks and greylag geese as well as the obligatory mallards, black-headed gulls and Canada geese. There is even a heath, part of an open expanse called ‘the Flats’ segueing from grass and copse to playing fields and divided into segments by the roads to Forest Gate and Manor Park. Nature here is raggedly alive, part of a landscape that is neither wholly picturesque nor municipal.

In that respect, Leytonstone and the surrounding area might bring to mind the landscapes tramped over by Richard Mabey in The Unofficial Countryside or the Edgelands explored by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts. They call such terrains ‘the new wild’, ‘the domain of the feral’ – and I recognise that mixture of built and natural, husbanded and neglected in my local area.

If you look at it one way, there’s no such thing as ‘wild’ anymore, now that our planet’s biosphere has been so comprehensively affected by human action. We have changed the weather, changed the ozone layer, changed the oceans and seas – and so there is no part of the planet and no living thing that has not been touched by us, even if only indirectly.1 If nature is in a constant state of negotiation with humanity over territory, adapting, as it experiences resurgence in one place whilst being pushed back in another, then that isn’t wildness. That’s ferality.

Feral. From the Latin fera: ‘a wild beast’. Since the nineteenth century, it’s denoted a lapse from domestication into wildness. Something once tame, no longer. We use it about people, too. And it’s borne of disadvantage, some way in which human society and structure conflict with an entity’s needs and well-being. I keep thinking of the cat that Farley and Symmons Roberts conjure for us:

Here, finding shelter in the old ruins and food in the overgrown wasteland outside, cats forget their pet names, swap the lap and sofa for the pile of discarded overalls, or the car seat with its sporty trim.

That feral cat’s transitions between wild and domesticated won’t have been easy. However attractively the car seat is presented (that ‘sporty trim’), it is ‘preferred’ to a lap and a sofa because its human companions abused or abandoned or neglected it. Still, that cat’s freedom – contingent, yes, and difficult – is powerful: it offers a possible way to keep living somewhere, to make ‘home’ by usurping or ignoring boundaries.

And by adapting: those pigeons behaving for a moment like waterfowl, treating rooftops like the cliffs their rock dove ancestors inhabited. A feral species alters its behaviour or alters itself, through successive generations, transforming to meet its new circumstances, a changed environment.

Feral is a good word, too, to describe my neighbourhood. Leytonstone itself seems to be all pieces and edges, cut in half by the M11 Link Road and the Central Line, connected by the latter to both the City proper and the woodland of Epping Forest, topped by a massive sunken roundabout (the ‘Green Man’) where roads from all the compass points converge. Wanstead Flats, where I spend a lot of my time, straddles the London Boroughs of Waltham Forest, Redbridge and Newham – though, as part of Epping Forest, it also comes under the City of London Corporation’s management.

This is my feral borough: Leytonstone, Waltham Forest, green spaces transgressing civic lines. But also more than that. It is a kind of borough-by-affinity, too, made by walking and loitering, looking and recording. It can be found in pockets, scattered throughout the city: on the towpath by the Regent’s Canal, in the corner of a Bloomsbury square, a cut-through behind a row of shops. Where plants grow, where quietness pools in corners, the feral borough is made; flickering into being around me. And if the city is a haunted place, a palimpsest, then the feral borough is part of what haunts it. Like the desire paths crossing municipal lawns, or the Parish boundaries delineated by Beating the Bounds, it sharpens with each foray. The imagination builds it as much as the physical, and so I make it not just as a walker or a loiterer but as a reader and a watcher, too. Beside me are the writers and texts that have been so important to me – and so are its fauna. They conjure it with me.

And so the feral borough materialises around me as wood pigeons and swifts give voice in a town beside the Severn river, goldfinch and pied wagtails feed at a university campus, a kestrel hovers above a service station carpark on the M40. Every encounter with these familiars is a moment of home and belonging, where my borough breaks its bounds, trespasses the limits of geography, comes roaring up to hold me. It’s not surprising its appearances occur at moments of intense emotion or difficulty in my life – for the feral borough is nothing if it isn’t also brought into being by emotion.

I started writing about this landscape and its flora and fauna almost as a way to stay in the city – for as the years wore on, London started to tire me out. It was my home, but it seemed to manifest everything wrong with my modern life: too fast, too loud, too crowded, too abrasive, too polluted, too littered, too much. And every day it brought me face-to-face with what we’re doing to the environment: the muck-pink film of haze over the horizon, the squirrel turning a still-wrapped Kit Kat between its paws, the burger wrappers caught in the hedge. Because of love and work, I had to find a way to keep living there, but I didn’t know how. Weirdly – or perhaps expectedly – it took the death of one of my closest friends, Tara, to make me see what I was missing. In those changed moments that follow a sudden death, my encounters with the world took on a peculiarly charged quality. I took to walking round the local wood, the parks, the heath – and the plants I saw took on what I can only describe as personalities.

And so I met the feral borough – or made it, or dowsed it, or tuned into it, or invoked it, or conjured it – and now I have inscribed it into these pages. When I started this book, I had no idea I would write something so personal. I thought I was writing a work of non-fiction, something easily categorizable under 'nature writing'. But as I wrote myself into connection with the flora and fauna around me, the entries themselves threw out suckers, sprawled over the fences I had put up – and my own life kept getting snagged on the vines. If the book was a beast, it was misnamed, not wanting to sleep in that kind of bed, refusing to stay put in the territory I allotted to it and doing things that sort of beast was not reputed to do. Its parents were definitely from different species. If it was a plant, it had been wind-blown or pigeon-shat far from its starting point.

So you might also think of this book as a series of bulletins wrung from an unreliable reporter by her encounters in this place. Or maybe they are a collection of greetings, in differing moods and ways, to the often unremarkable local wildlife that shares my habitat – and by extension to the common flora and fauna that inhabit Britain. There have been times when I never thought I’d feel at home anywhere nor that I’d ever be able to call myself a local, but here on this street, it seems I’ve become embedded. All that noticing and writing wasn’t just helping me do the work of grieving, it seems. It has also helped me think myself into this place. Home. And so this book celebrates the joy of being and staying local – extremely so, sometimes restricted to the few metres outside the front door, as the pandemic and the English lockdowns of the last couple of years have forced us to be.

I’m writing this while the neighbours clear up in the kitchen after the evening meal and scaffolding announces another loft conversion. To live here is to realise that everything – houses, roads, people – is always in relationship with everything else. Human and non-human alike, enmeshed as we are, we all transform or mount incursions. The dahlias we planted in our tiny garden go rampant and crowd out the tomatoes, hops take root in the grass verge up the road. ‘Nature’ is everything and everywhere in the city. It’s blocked drains and street-wide puddles, black mould on windowsills, TB, asthma, scabies. And coronaviruses. It’s raised voices and vomit on the platform, the dark mice at Holborn with the half-tails. It’s parakeets and blackbirds, the howl of planes and the bone-drilling imperatives of power saws. It doesn’t wholly submit to human regulation, even as it’s changed and harmed by what we do, by our coffee cup lids and carrier bags, by the times we hop into the car instead of taking the bus, by the towers we build and the spaces we pave over and the way we don’t listen to what’s around us – especially not to each other.

I’m not sure how much longer we’ll stay in Leytonstone. Jobs again – and the pull of loved ones in other places, the toll the London air takes on my asthmatic lungs. In the meantime, there is the borough. I go outside onto the high street and here we all are: little kids ogling the cakes in the window of Greggs, the men chatting on their way to Mosque. The late sun uplights a triangular cloud in pink as twilight approaches. I look up from the pavement and there are the parakeets, speeding overhead in full squawk.

To live in the feral borough then is to be in kinship with everything outside my door. Jackdaws on the bus shelter roof. Someone’s snuffling dog, straining against the lead. Those feral pigeons – a fitting emblem for this book – following a buzzard over the terraced streets, keeping the predator firmly in view. That counterpoint between the rare and ordinary, wild and domestic and whatever lies between the two is part of what I love about my home. Living here has taught me so much: to be with both nature and the city, noise and quiet, life and death, to hold all that, all at the same time. Because we humans are feral too, and life is brief.

1 And now there is this:

Nanoplastic pollution has been detected in polar regions for the first time, indicating that the tiny particles are now pervasive around the world. […] Analysis of a core from Greenland’s ice cap showed that nanoplastic contamination has been polluting the remote region for at least 50 years. The researchers were also surprised to find that a quarter of the particles were from vehicle tyres.

Damian Carrington, ‘Nanoplastic Pollution Found at Both of Earth’s Poles for First Time’, The Guardian, 2022.

Artificial Tree

Artificialis arbor

By which I don’t mean the dishevelled plastic affair shoved into the cupboard under the stairs, but this oblong, metal tower, parked beside the sculpture at the bus station, with seats of attractive wood set into its base on each side and a series of shelves rising to about four metres, jammed with rolls of moss and houseleeks. This is a city tree – or more properly, a CityTree; ‘The World’s first biotech pollution filter.’ It has a water tank and sensors that monitor pollution levels, it can upload the data wirelessly, it can ‘quantifiably improve urban air quality’. I’ve passed it before while running errands; a curious structure parked on a barren island of paving between road and bus park.

I visit it properly one clear day in late summer, a day when London’s pollution levels are at the top of the scale. We’ve been advised not to exert ourselves too heavily, especially if we are older or have heart or lung problems. Asthmatics should carry their inhalers. The strong sunshine is reacting with the city’s pollution and the lack of wind prevents it from dispersing. When I emerge from the foot tunnel onto the bus concourse, I start to cough; the stink of bus exhaust is palpable. This area around the station is one of the most polluted in Waltham Forest, placed as it is right beside the M11 Link Road, carved through Leytonstone and Wanstead in the late nineties despite the extended protest.1

Ironic, then, that Leytonstone has acquired a paean to its air quality, albeit one written in 1703. Joseph Harris’s ‘Leighton-Stone-air, a poem. Or a poetical encomium on the excellency of its soil, healthy air, and beauteous situation’ was written on the occasion of the founding of a ‘Latin boarding school’ and makes much of ‘Healthy Leighton’s Eppen Plain’ and the ‘Lovely Villa’ wherein, presumably, the school will be based. I do not think Harris would praise quite so lavishly the ‘Odours of thy Hemisphere’ if he were standing in this spot beside the station.

The cyborg tree is not doing well. The moss is tan and shredding out of its rolls. Whole blocks are missing from the shelves, exposing the diamond metal grid behind it. There are a few houseleeks in a bottom corner showing some green, but the rest are grey and desiccated.

Street trees have a notoriously difficult time of it. Their roots are strongly curtailed by the severely compacted soil under pavements and tarmac. Above ground, they have to contend not only with random vandalism or accidental car damage, but higher urban temperatures, dog piss, gritting salt and pollution too. When these conditions weaken them, they fall prey to disease and bugs; most have a shorter life expectancy than their non-urban counterparts. And this strange, hybrid creature – part artifice, part organic – seems to be no exception. Houseleeks belong to the genus Sempervivum – ‘live forever’ – but even they are succumbing to conditions.

I take a couple of pictures on my phone, adjust my glasses and huff on my inhaler. Donna Haraway has said that we are all cyborgs – ‘chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism’. With medication in my system and this device parked on my nose, I fit the bill. One cyborg meeting another, neither of us entirely thriving in the Odours of the Eppen Plain.

1 People camped out in trees, the ‘micronations’ Wanstonia and Munstonia were established and buildings condemned for demolition were occupied. The road was still built, although the 491 survived as a squatted art gallery until the late 2010s. It’s now a block of flats.

Pride of Leyton

Dianthus caryophyllus var. ‘Pride of Leyton’

The carnation variety ‘Pride of Leyton’ is a picotee – that is, a flower with a different colour or shade at its petals’ edges, in this case, darker and lighter purple. But ‘Pride of Leyton’ might not exist any longer.

It first appears on record in 1887, when Henry Headland exhibits it at the annual exhibition of the National Carnation and Picotee Society, Southern Section, receiving a first-class certificate of merit for his ‘very promising flower of excellent quality’. Headland, described in the report as a ‘surgical instrument maker’, is living at the time of the 1891 Census with his wife and children at 82 The Firs, Leyton. His occupation is listed as ‘brass finisher’. The family share the residence with Henry’s in-laws, two of whom – the father, Richard, and brother-in-law, William, are florists. It’s easy to track Henry’s life and career through the years; he wins first place at the annual exhibition in 1888 with ‘Pride of Leyton’ in the ‘Picotees, single bloom – light purple edge’ class, and second in ‘Picotees, single blooms – Light Red edge’ with a variety named ‘Souvenir of H. Headland’, possibly in memory of his own father, also named Henry, a silversmith who died in 1886. In 1894, he withdraws from the National Carnation and Picotee Society’s committee – and by 1901 he is working as an electrical engineer. He lives to the age of ninety and sees his son, Henry William, go into the electrical engineering trade as well, moving with his own family to Hainault Road in Leytonstone, less than a quarter of a mile away.

The year that Headland leaves the committee, one Mr Nutt – who has shown blooms in previous years within the same categories – wins first place at the annual exhibition in a single specimen category for ‘Pride of Leyton’. Growers were clearly sharing their plants at these shows. But ‘Pride of Leyton’ itself is harder to track. I can find no mention of it – nor ‘Souvenir of H. Headland’, for that matter – in the Classification Booklet of the British National Carnation Society, nor in the Royal Horticultural Society’s International Dianthus Register. It has slipped from view.

Did it prove less reliable than hoped? Was it abandoned? Did it hybridize with another variety? There is record of Dianthus ‘London Lovely’ and Dianthus ‘London Brocade’, Dianthus ‘London Joy’ and Dianthus ‘London Delight’. There is Dianthus ‘London Poppet’. There is Dianthus ‘Suffolk Pride’ and Dianthus ‘Devon Pride’ and Dianthus ‘Cannup’s Pride’. There is even ‘London Pride’; an old name from before the eighteenth century for Dianthus barbatus (Sweet William), though it’s now applied to Saxifraga × urbium. But ‘Pride of Leyton’ has vanished. It is a ghost plant. I can’t trace its lineage, can’t find its descendants. It only exists in paper and record, tucked away digitally, haunting archival glades.

Somewhere, in these two or so miles, there’s a piece of land that retains the footprint of a shed or greenhouse where ‘Pride of Leyton’ was bred. Maybe there’s a trace of that vanished picotee dug into the soil. For under these acres that have been paved over and on which our houses have been built, are other gardens, ghost gardens, entire ghost nurseries.

Leytonstone and the surrounding area was a place for gardeners and horticulture until remarkably late in its history. At Mr Headland’s time, it is undergoing the rapid change that transforms it into a London suburb proper. The city is fast encroaching: market gardener James Sweet, for example, has to leave Leyton ‘on account […] of the increase of smoke.’ Nevertheless, at the turn of the century, Leytonstone is still the site of several nurseries and market gardening enterprises. There is the ‘American Nursery’ on Grove Green Road, known for its fine collection of trees, that passed through several hands to horticultural auctioneers Protheroe and Morris, who had already established nurseries in the area. There is the Wallwood Road nursery, run by John Ward who started out as a gardener for the local wealthy, growing orchids amongst other things, before buying an acre of ground in Leytonstone and going into business with his sons: ‘the entire acre was soon covered with glass.’ In 1901, Leytonstone alone harbours 217 male and 20 female ‘gardeners (not domestic), nurserymen, seedsmen, and florists’.

And its history as a centre for botany and horticulture goes still further back. Only four miles away is the estate inherited in 1742 by Richard Warner, a lawyer born into a banking family, who promptly turned it into a botanical garden. A portrait made by Francis Milner Newton in 1755 shows a round, satisfied-looking man with a long, straight nose, one hand tucked between the front buttons of his waistcoat and resting on his stomach. This is the man who imported a new variety of grape from Hamburg in 1726 and played a part in naming a gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis). The author of the 1771 work, Plantae Woodfordienses: A Catalogue of Less Perfect Plants Growing Spontaneously about Woodford in the County of Essex. A man of consequence.