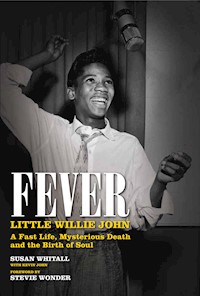

Fever: Little Willie John's Fast Life, Mysterious Death, and the Birth of Soul E-Book

Susan Whitall

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

"Little Willie John is the soul singer's soul singer." - Marvin Gaye "My mother told me, if you call yourself 'Little' Stevie Wonder, you'd better be as good as Little Willie John." - Stevie Wonder Little Willie John lived for a fleeting 30 years, but his dynamic and daring sound left an indelible mark on the history of music. His deep blues, rollicking rock 'n' roll, and swinging ballads inspired a generation of musicians, forming the basis for what we now know as soul music. Born in Arkansas in 1937, William Edward John found his voice in the church halls, rec centers and nightclubs of Detroit, a fertile proving ground that produced the likes of Levi Stubbs and the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Smokey Robinson, and Hank Ballard and the Midnighters. One voice rose above the rest in those formative years of the 1950s, and Little Willie John went on to have 15 hit singles in the American rhythm & blues chart, with considerable cross-over success in pop. Some of his songs might be best known by their cover versions ("Fever" by Peggy Lee, "Need Your Love So Bad" by Fleetwood Mac and "Leave My Kitten Alone" by The Beatles) but Little Willie John's original recording of these and other songs are widely considered to be definitive. It is this sound that is credited with ushering in a new age in American music as the 1950s turned into the 60s and rock 'n' roll took its place in popular culture. The soaring heights of Little Willie John's career are matched only by the tragic events of his death, cutting short a life so full of promise. Charged with a violent crime in the late 1960s, an abbreviated trial saw Willie convicted and incarcerated in Walla Walla Washington, where he died under mysterious circumstances in 1968. In this, the first official biography of one of the most important figures in rhythm & blues history, author Susan Whitall, with the help of Little Willie John's eldest son Kevin John, has interviewed some of the biggest names in the music industry and delved into the personal archive of the John family to produce an unprecedented account of the man who invented soul music.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 382

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FEVER

LITTLE WILLIE JOHN

A Fast Life, Mysterious Death and the Birth of Soul

THE AUTHORIZED BIOGRAPHY

SUSAN WHITALL

WITH KEVIN JOHN

TITAN BOOKS

Fever: Little Willie John’s Fast Life, Mysterious Death and the Birth of Soul

Print edition ISBN: 9780857681379

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687968

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark St.

London, SE1 0UP

First edition: June, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Susan Whitall & Kevin John 2011. All rights reserved.

Edited by Nadine Käthe Monem

Front cover © 2011, Frank Driggs Collection/Getty Images

“Blue Wing” used by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation “Fever,” “Talk To Me, Talk To Me,” “Walk Slow,” all used by permission of Fort Knox Music, Inc. and Hal Leonard Corporation

“The Hucklebuck” used by permission of Bienstock Publishing Company and Hal Leonard Corporation “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” written by Jimmy Cox

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please e-mail us at: [email protected] or write to Reader Feedback at the above address. To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed in the United States

FEVER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

Fever: Little Willie John’s Fast Life, Mysterious Death, and the Birth of Soul

Bibliography

Discography

Acknowledgments

“Willie John was a singer’s singer. There is no deeper blues than his–and only his–“I Need Your Love So Bad,” there is no rock ‘n’ roll quite like his “All Around the World,” there is no ballad performance as simultaneously easy, swinging and erotic as his–and only his–Fever.” He could kill you with a George Jones song. He sang like he owed nothing to anybody and the world might forget but he never would. His voice isn’t the voice of a lot of people’s hearts, I guess, but it’s the voice of a few of us. We’re the fortunate ones.”

– Dave Marsh

I’d like to dedicate this book to the memory of my father, William Edward John, professionally known as ‘Little Willie John.’ Many things have been said and written about my father over the years. I believe he would be happy to see that we finally set the record straight. And also to my mother; without her consent and approval I would have not embarked on such a project. I love you, Mom!

I’d like to thank my brother, Keith and my wife, Cathy, for their special and unique contributions to this book, and my two sons, Kevin II and Keith—this is your story too, it’s part of your heritage, your roots! On behalf of the entire John family, I thank Ms Susan Whitall, for her vision, professionalism and great patience. Susan, it’s been a pleasure and a learning experience working closely with you. Finally, a special thanks to Mr Clarence Avant, a man who did not forget his old friend, and who continues to speak well of him more than 40 years later.

As a young man, I had four wishes regarding my father’s musical legacy. Firstly, I wanted my father to be recognized and inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Secondly, I wanted my father’s final recordings to be released and made available to those who appreciate his talent and love his music. Next, I wanted to be part of a book project that would accurately and tastefully tell the interesting and poignant story of my father’s life and music. Finally, it was my hope that his story would be the subject of a motion picture. The first three of these four wishes have now come true. It is my hope that the fourth will also become a reality.

—William Kevin John

FOREWORD

BY STEVIE WONDER

My first time hearing Little Willie John, I must have been seven or eight years old, at the most maybe nine. It was amazing. I remember listening on the radio and hearing, “If I don’t love you baby, grits ain’t groceries...” They said he was a young boy from Detroit and how talented he was, that he was going to be performing at the Fox Theater. I was really excited about his voice and what he was able to do with it. He was unique—the fact that he was able to sing high, that he was able to do the riffs that he did.

There was a DJ in Detroit who would always play his music, all the time; his name was Ernie Durham and he was on a station called WJLB. Back then they would play a song, and if they liked it, they would play it over and over. Willie’s songs would play, and Ernie would say “Whoo ooo eee!”

Growing up singing as a little boy, everybody who was a singer would try to copy or do a better riff than the next person, similar to how rappers do snapping today. Singers would sing in the backyards or wherever, there would be competition on who could do the riffs. Willie and Jackie Wilson were the ones everyone would listen to for the riffs. They’d say, “Wow, you’ve gotta hear this riff, LWJ did this riff!” “Well Jackie Wilson did that riff, yeah, but Little Willie John did this riff here!”

You can hear Little Willie John when you hear Usher. You can hear him doing those riffs sometimes, the kind that Willie would have done. What makes a singer unique and long lasting, at the end of the day, is if they are able to sing a riff to any chord progression and it makes sense. You’ve got to also know how to do it tastefully. Some people over-sing, you say, “OK, can you get back to the melody?” Willie had a way of singing the song, going out but coming back, similar to great jazz musicians like Miles Davis or Coltrane. There has to be a place where it’s melodic enough without becoming boring.

I think the person who was most inspired by Little Willie John is his son. It is an honor that I’ve been blessed to have the son of such a great singer be a part of my career—my life, my group—and it’s just amazing how God works that he would allow that to happen, that Keith would come into my life through someone who was a big fan of Little Willie John’s, Charlie Collins. Meeting Keith and Kevin John, I saw how their appreciation for their father didn’t limit them in having their own uniqueness.

You hear his influence in lots of people who sing today. It’s impossible for people to talk about rhythm & blues and talk about singers and not mention the voice and talent of Little Willie John as being one of those great people.

PROLOGUE:IN SEARCH OF LITTLE WILLIE JOHN

Every few years someone comes up with ‘the last untold story’ in popular music. I won’t say Little Willie John’s story is the last, but it is one of the more unfortunate omissions from the annals of American rhythm & blues history.

Over the decades, Willie’s life and career have been boiled down to a shallow, sordid haiku: Great talent, a violent assault in Seattle, prison and then death. Sketchy details that do nothing to explain who he was, where he came from or why he sounded the way he did. I’ve always loved Willie’s voice, from when I was a child growing up in Philadelphia and I first heard “Sleep” playing on WFIL. I had no idea who he was, or that his voice and his story would tug at me so many years later.

In my early 20s, I was on staff at Detroit’s Creem magazine, while it was mostly riding the mid 1970s wave of rock, punk and metal. I was always drawn to rhythm & blues, the music that made rock ‘n’ roll possible, and was equally fascinated by how integral the Detroit scene was to it all. When I left Creem for the Detroit News in the early 1980s, I was able to dig even deeper into the city’s musical history, and I had the privilege of interviewing many of the singers and musicians who helped put Detroit on the map. In talking to Joe Messina, Joe Hunter and Uriel Jones—members of Motown’s studio band, the Funk Brothers—the discussion would inevitably return to their early days on the Detroit club scene, painting a fascinating picture of how the city’s jazz and rhythm & blues scenes intersected and influenced one another.

Right in the middle of it all was this largely forgotten singer, the brash kid who jumped onstage with Count Basie and the big bands, became Detroit’s first massively popular solo rhythm & blues star, and laid the groundwork for the singers and groups of the Motown and soul-dominated 1960s.

He died so long ago, in the spring of 1968, barely 30 years old. But in the world of rhythm & blues, Willie is like the mystical dark matter that astrophysicists search for; an essential but unknown link that seems to hold the universe together. If Willie hadn’t lived for those fleeting three decades, we would have had to invent him to explain how rhythm & blues segued into soul. When I interviewed Willie’s sister, Mable John, in 1995 for my book, Women of Motown, and she described the friendly, competitive relationship between Willie and Berry Gordy, I was even more intrigued. The diminutive rhythm & blues genius, usually laughing in those grainy black and white photographs, always eluded definition. I wanted to know more, but filed it away for “someday.”

One day, out of the blue, Willie’s son Kevin contacted me. He wanted to thank me for mentioning his dad briefly in a story for The Detroit News, but he also wanted to talk about Willie’s music. A month or so later, I was at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland with the Funk Brothers when I happened to run into Kevin. He asked if I was interested in writing a book about his father. Interested? I was mesmerized.

Part of the mystery with Willie is that so many of us never got to see him live, or even on tape or film. Although he appeared countless times on local Detroit television, and on American Bandstand three times, The Tonight Show (with Jack Paar), and every other regional music show there was at the time, we only have one clip of Willie in motion. He isn’t singing, alas, but whacking claves, a percussion instrument, in a scene on the hip early 1960s TV series, Route 66. It’s a tantalizingly short, but poignant clip. The way Willie nods his head while playing the claves is exactly the way his sons and grandsons move. “The John head nod,” Kevin called it.

One way I did get closer to Willie was getting to know his family, especially Kevin, who provided a wealth of family stories, letters and photos and helped to set up and conduct interviews. Kevin, who gave up a career in music to raise a family in Detroit and pursue his religious interests, introduced me to his mother, Willie’s widow Darlynn, as well as his brother Keith, a singer, songwriter, backup vocalist for Stevie Wonder, and producer in his own right. Darlynn once told me, if I wanted to experience what it was like to be around Willie John, I should sit between Kevin and Keith and I’d get a stereo version. Kevin resembles his father, and both he and Keith are constantly singing, joking and generally exuding the hyperkinetic male “John” energy.

There was a lot of joy in the stories Willie’s family and friends told in the time we spent together, but there was also a lot of pain. Darlynn had never spoken about much of these events outside of the family circle. It is only because her son Kevin so badly wanted for his father’s story to be told did Darlynn overcome the distress of remembering Willie’s final years, and open up with stories that had been buried for a lifetime. I am so grateful that she did. We don’t shy away from Willie’s sad final days here, but we also celebrate the tremendous talent that makes his story relevant and vital all these years later, hopefully capturing Willie in all of his multi-dimensional human complexity.

Susan Whitall2011

Anyone with information about Willie, photographs or video, please contact Susan Whitall or Kevin John at [email protected]

1

MAMA WAS A GENIUS

Lying in the dark of the bedroom he shared with his brothers Ernest and Raymond, Willie John would dream out loud. He would be a famous singer one day. Onstage at the mic, he was dressed in a knife-sharp, double-breasted suit, his hair plumped up in a fresh process. In those whispered dreams, he sang in front of Duke Ellington’s band and partied with Sugar Ray Robinson. He drove a leaf-green Cadillac home to a sunlit, stucco house with lemon trees in the backyard.

“It all came true,” said brother Raymond. “Everything he said.”

The boys lived in a project in the north end of Detroit, a flimsy, one-story house thrown up for the workers during the Second World War. Seven John siblings were crammed into the tiny place with their parents, Mertis and Lillie. But they felt safe there, in a project set aside for blacks in postwar, segregated Detroit.

Mertis and Lillie John brought their children from Arkansas to Detroit in 1941, part of the second Great Migration from the South that drew blacks and Appalachian whites to the arsenal of democracy. Factories were thrumming 24 hours a day making tanks, Jeeps and bombers to vanquish the Nazis—and there was work to be had.

The first Great Migration, between 1910 and 1930, saw Detroit’s population explode from 465,766 to 1.5 million in 20 years. Many of those on the human highway streaming into the city were Southern blacks seeking jobs and an escape from the hardship and dangers that loomed below the Mason–Dixon line. In 1910, Detroit’s black population figured 5,741 people. By 1940, it had grown to 149,119. When America entered the Second World War, Detroit needed a lot of muscle to keep the factories in full roar, that need spurred on a second influx from the South, and by 1950 there were more than 300,500 blacks in the city. Although they were mostly doing jobs nobody else wanted to do, the pay gap between blacks and whites wasn’t as large as it was in the South. Mertis John knew that, and he also knew that a dirty job in a Detroit foundry beat the Arkansas paper mill any day.

Both the Robinsons, Willie John’s maternal relatives, and the Johns were originally from Louisiana. There isn’t much information to be had about the Johns, but we do know that Lillie’s parents, Edward and Rebecca James Robinson, were farmers in the town of Angie, about 60 miles from New Orleans. They had five children: Olivia, Eula, Lillie, Andy and Clyde. Like many Southern families, the Robinsons were a mix of black, white and Native American stock. They were a musical family, hosting Friday night fish fries in Angie, where neighbors, aunts, uncles and cousins would ride over on horseback to play music, drink homemade whiskey and sing songs together.

In later years, both Willie and his sister Mable told of how their mother, Lillie, would sneak out as a girl to sing in New Orleans’ nightclubs. In Willie’s telling (always the most dazzling account) Lillie sang with Louis Armstrong, no less. Whomever she was with, singing in nightclubs was forbidden, and Lillie knew it. She gave up all thought of a singing career when, in early 1930, she married Mertis John, who worked in the local paper mill steering logs into the grind.

Their first child, Mable, was born in Bastrop, Louisiana that November. When Mable was still an infant, the family moved to Arkansas, where Mertis found a job at a larger paper mill in Cullendale, doing the same thing he did in Louisiana. In 1932, Lillie gave birth to Mertis Jr, she had Haywood in the following year and Mildred a couple of years after that. On November 15th, 1937, William Edward John was born, named after each of his grandfathers. The family called him William or Edward, although after he rose to fame, they called him ‘Willie’ along with the rest of the world. His brothers would sometimes call him ‘Fever’ behind his back, but to his mother, he would always be Edward. The birth of Delores John followed a couple of years after Willie’s, in 1939, and Ernest (or EJ) was the last John born in Arkansas, in 1941.

When the Johns arrived in Detroit in 1941, the sidewalks were teeming with shift workers and the sky choked with factory smoke. At night, the workers headed for the bars, and the sound of jazz and blues could be heard from every corner. The Southern blacks and whites who flocked to Detroit for work brought their music with them, making for an intriguing blend of blues and country music in adjoining neighborhoods, in the clubs and on the radio. Lillie never touched alcohol, but her husband enjoyed a drink every now and then. Both could play guitar, and Mertis Sr could imitate any instrument using pots, pans and whatever else was handy. He could also impersonate any singer around, to the delight of his children.

Prohibition started in 1917 in Michigan, two years before the Eighteenth Amendment was nationally ratified, banning the manufacture, sale and distribution of alcohol. Fortunately for some, Detroit was just a short boat ride away from Canada and its legal whiskey, so the booze was “imported” to the Motor City’s nightclubs, bars, saloons and beer gardens. Most of them offered live music in order to keep patrons out longer, drinking more of the whiskey supplied by the Purple Gang—the tough Jewish gang members from Detroit’s east side who manufactured and distributed bootleg hooch to much of the Midwest. After the Eighteenth Amendment was repealed in 1933 and beer, wine and liquor flowed legally again, the clubs were shorn of the lawless ‘blind pig’ tag (the name Detroiters still use for a club serving liquor illegally, referring to the fact that the police would often look the other way—making for a ‘blind pig,’ as it were). The innumerable watering holes all over metro Detroit served as the infrastructure for a thriving jazz and rhythm & blues music scene in the 1940s and 50s.

The city’s exploding black population also meant a sharp growth in the number of black churches, a proving ground for singers, gospel quartets and choirs. Detroit became a major stop on the gospel circuit, and ministers like the Reverend C.L. Franklin, Aretha’s father, would host visiting gospel stars like the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Soul Stirrers featuring Sam Cooke.

In 1941, Mertis John installed his family in a cramped apartment at 2120 Monroe Street near the Eastern Market, the distribution hub for Detroit’s food supply. The John children liked Monroe Street, Mertis Jr remembered how truck drivers would call them across the street to pick up candy from “broken” boxes. But his parents wanted something better. Several years and several moves later, with Mertis Sr working at the Dodge Main assembly line in Hamtramck, the family moved into 14503 Dequindre, a project just south of Six Mile Road in northeast Detroit. Originally built as temporary housing for wartime factory workers, by the mid 1940s, the area was set aside for Detroit’s black population.

There were painfully few housing options for families like the Johns, most were crowded into a few neighborhoods on the east side, around Hastings Street. Detroit was strictly segregated throughout the 1940s, and overcrowding fueled by the wartime boom in factory work caused simmering resentments both in the raggedy east side neighborhoods where blacks were forced to live, and on the city’s west side avenues, canopied with lush Dutch elm and oak trees. There weren’t enough apartments or houses for white factory workers, much less for blacks barred from those neighborhoods by restrictive covenants.

In this overheating melting pot, it was a step up for the Johns to have their own place. The project houses were basically drywall slapped up into square boxes, with walls so thin everybody called it ‘Cardboard Valley.’ On hot summer nights, families escaped their sweltering houses to spread blankets on the grass and sleep under the stars, undeterred by the lights and grinding noises coming from the nearby Vlasic pickle factory. Despite the cramped and sometimes crumbling conditions, the neighborhood felt safe enough for residents to leave their doors unlocked, and allow their children to run the streets, and in and out of neighbors’ houses.

Daisy Stubbs and her family lived across Dequindre on the project’s west side. Daisy was a frequent visitor to the Johns’ kitchen, where she would drink coffee and catch up on news. Her son Levi, known as ‘Lee’ in the neighborhood, hit it off with Willie John, who was a year younger. It was hard not to hit it off with Willie, he was a lively, charming boy, a spinning bundle of energy with nerves always close to the surface. That nervousness was sometimes aggravated by an occasional epileptic seizure, usually brought on by fatigue or stress. The Johns didn’t talk much about Willie’s seizures, reflecting a common shame associated with epilepsy in the 1940s and 50s. Some of his siblings believe he was prescribed phenobarbital, but older brother Mertis Jr doesn’t recall epilepsy being a major problem in Willie’s childhood. It was only later, when he was a touring musician, that the seizures would become a problem, particularly if he wasn’t eating well or if he was drinking too much and taking too many drugs.

Despite having to cook, clean and look after such a large brood, Lillie, known to all as ‘Mother Dear,’ was on top of things. Fifty years later, EJ and Raymond still talked about how their mother could drain a cheap can of butter beans, rinse the beans with water and cook them in butter, producing a kind of ambrosia the boys almost preferred to a steak dinner. “Mama was a genius,” Raymond said. Years later, Willie would insist that his wife make beans the same way.

There was always something to eat in Lillie’s icebox, usually beans and greens. “A lot of us was in that house, and she would look out for me just like she looked out for one of her sons,” said Mack Rice, who lived in the neighborhood. A who’s who of Detroit music history grew up in the north end, among them Smokey Robinson, Aretha Franklin, Bettye LaVette, Lamont Dozier and Jackie Wilson. “Everybody was your cousin,” Rice said. “If you had met Jackie Wilson back in the day, you would have been his cousin, too!”

Just as her mother’s house in Louisiana was immaculate, so was Lillie’s house in Detroit. “You could do surgery in this woman’s house,” said Harry Balk, Willie’s first manager. “The furniture wasn’t new, but it was so clean. And here’s people who lived, not in the ghetto, but close by it. If ever there was an angel on earth, it was Mother Dear.”

If he wasn’t sleeping or eating, Willie was outside. He often darted across busy Dequindre to visit Levi Stubbs and another friend, Stanley Lee. In the summer, the three boys would crawl through the fence just south of the project and sneak into the reservoir built by auto magnate Henry Ford for a swim. Willie was always hustling. In the 1940s, with the factories running all day and night, an energetic kid could make money all over town. Despite the long hours, Mertis Sr worked at Dodge Main, with a brood of seven (then eight, then nine) children to feed, there wasn’t much money left over for luxuries. But Willie’s pockets always jingled, to the amazement of younger brother EJ. A Coca-Cola cost a whole nickel, and those nickels came quickly.

Willie showed his little brother how to shine a man’s shoes in the 30 seconds it took to ride the escalator to the second floor at the Woodward Avenue Sears store. Older brother Mertis Jr delivered the afternoon Detroit News, while Willie threw the morning Free Press. Even baseball was a money-making opportunity. Jackie Robinson had not yet integrated major league baseball as the first black player, and he often played at the Negro League’s Dequindre Park, home of the Negro League Detroit Stars and just a short walk down the street from Cardboard Valley. During games, Willie and his friends hovered outside the ballpark, waiting for a home run ball to come flying over the wall, so they could pick it up and sell it back to the team for a dollar.

Willie and the boys spent their nickels and dimes at the corner store on Six Mile Road. The boys would wander west on Six Mile down to Palmer Park, where they could watch the tennis players and check out the horse-drawn carriages taking leisurely rides around the park.

Both Lillie and Mertis John were devoutly religious, although Lillie was the more faithful churchgoer. In Louisiana, she grew up going to Mary’s Chapel, a United Methodist church. In Detroit, the Johns attended several different Holiness churches, including the Triumph Church on South Liddesdale. Lillie sang gospel songs around the house, teaching her children the words. “But she didn’t teach Willie how to sing,” his brother EJ said. “Nobody did.”

In the end, Willie’s voice was the easiest hustle. He had a sensuous, eerily mature voice full of depth and nuance—“a blessing from God,” his mother called it. It came bursting out of his skinny chest as if it was the most natural thing in the world. Willie could sing anything, even the hillbilly music he heard on the radio. “He was always singing,” said EJ. Four years younger than Willie, EJ was almost exactly the same size as his big brother, but he was as quiet as Willie was gregarious.

For Willie to stand out as outgoing in the John family took some doing. Mable, as the oldest sister, was used to taking charge and issuing instructions. Petite and well-groomed, she had most things figured out, and a good few opinions that needed to be aired. Mable showed brother Mertis Jr how to slow-dance in one easy lesson, and taught him how to type as well. She managed an introduction to Mrs Bertha Gordy of the energetic, enterprising Gordy family—with business interests in printing, construction and retail. Mable could see that the Gordys were going places, and she apprenticed herself to the matriarch of the family, helping with typing, answering the phone and selling insurance door to door. When Mrs Gordy discovered Mable’s interest in music, she introduced the girl to her son Berry, an aspiring songwriter.

Mertis Jr wasn’t lazing around, either. In high school he worked at a car wash, then started night shifts at the Dodge Main factory where his father worked, while still going to his high school classes during the day. “I made a living,” Mertis said. “I bought my books, my clothes. I bought a car in my own name. And I was nothing but a kid.”

Willie wasn’t about to go into the factory. He was interested in music, sports and girls. EJ remembers even a walk with his brother would usually end up with Willie singing, and a couple of ragtag neighborhood kids following them around enjoying the tunes. Once Willie had made the connection between music and money, his path in life became clear. He entertained customers at the candy store in exchange for treats, and Mertis Jr once found his diminutive brother standing in the middle of a crowd on the sidewalk, singing his heart out as people tossed nickels and dimes his way.

It helped that Willie was a charmer, his small face set off by large, expressive eyes and powered by a ferocious bravado. One summer day in the mid 1940s, Willie, Levi Stubbs and some friends were deploying one of their favorite hustles. Willie knocked on a neighbor’s door while the other boys headed to the backyard. When a woman answered, Willie flashed his most endearing smile and asked the lady of the house if she wanted to hear a song. Hearing no objection, Willie broke into a hymn, pouring his heart into every note. The neighbor went to get her purse, while out back, Levi and the boys were picking her cherry tree clean.

Willie’s schooldays started with a bang. On the first day of school, when his teacher at Duffield Elementary asked him to do something he didn’t want to do, Willie threatened to set his big brother, Mertis Jr, on her. In the 1940s, Detroit’s public school teachers were allowed to use discipline, and that teacher wasted no time in locking Willie in a closet so he couldn’t make good on this threat. Mertis Sr worked the afternoon shift, so he had to be awakened from his daytime nap to go pick up his mischievous son. A whipping followed when they got home. “An unforgettable one,” according to brother Mertis.

Another time, Willie swiped a pair of glasses from a near-sighted girl in his class. He wore the glasses home, claiming that he’d failed the school eye test. Mertis continued to question his son, and wasn’t buying the answers he was getting. Sure enough, that evening Duffield’s principal came by the house to inquire after the missing glasses, only to find Willie wearing them. Surely now, a world-class whipping was on the horizon, his siblings thought. Instead, Mertis got a large burlap sack, put his small son into it and hung the bag from a door. There Willie would stay, his father said, until he confessed and apologized. Willie didn’t cry, and he wouldn’t say he was sorry either. Instead, for hours the boy prayed and asked God to bless both his mother and father. He sang every gospel song he knew, at full volume. Willie wasn’t relenting, but neither was his father. Finally, two hours into the ordeal, Lillie begged her husband to take the boy down from the door and set him free.

Levi Stubbs and Willie were running the streets of the north end, both out of sight of their loving but overwhelmed mothers. Long summer days with no supervision stretched ahead of them. They both ended up in minor juvenile trouble, doing brief stints at the Moore School at the corner of Hague and Oakland, where the Detroit public school system sent its disciplinary problems. Willie was in the eighth grade at Cleveland Jr High School when he was caught in a compromising position with a girl on school property. He spent a year at Moore, between 1951 and 1952, moving on to Pershing High School once he’d done his time. Young Willie wasn’t the only kid who ended up at Moore and moved onto better things; Uriel Jones (of Motown’s Funk Brothers), Norman Thrasher of the Midnighters, and Lamont Dozier were just a few of the many Detroit musicians who were sentenced to a stint at Moore. Thrasher, four years older than Willie, was just getting out when Willie was coming in. “We were mischievous in regular school, acting up. Using bad language. So they sent us to Moore school, where there was zero tolerance,” Thrasher said.

Fortunately for the wayward boys who later became music men, a teacher at Moore managed to get through to them with both music and discipline. “Mr Irvin,” Thrasher said. “We had a glee club and we sang all over the state, under the direction of Mr Irvin. And he would talk to each one of us like a father, trying to keep us out of all difficulties when it comes to life and young girls. He had horror stories that made us not want to see any young girls when we came of age.” Uriel Jones was only half-joking when he credited the teacher with diverting him from a life of crime.

Later, Willie told of being deputy choir director under Mr Irvin. It wasn’t Willie’s first experience of music instruction, of course. He was taught breath control and enunciation by his Detroit Public School music teachers, which served him well in later years when he stood in front of a swing orchestra, expected to sound like a man of the world, or when he was singing the most low-down blues, sounding like a man of experience. Willie also took private singing lessons at the Detroit Conservatory of Music on the Wayne University campus, west of Woodward. “I wanted to be more than just a singer,” Willie said. He was singing classical and opera. “My earliest ambition was to be another Paul Robeson or even Caruso. When my money gave out, I gave up classical music and stopped studying it. We were poor people.”

In 2006, after Levi Stubbs had suffered several strokes and retired from the Four Tops’ touring schedule, Darlynn John and Willie’s sons Kevin and Keith visited him at his Detroit home. Darlynn and Clineice Stubbs had maintained close ties over the years, brought together by their husbands’ friendship, but also their common background as dancers married to singers.

Levi still exuded the presence and charisma of the born lead singer as he sat, immaculately dressed, in the Stubbs’ serene living room overlooking a golf course fairway. He spoke haltingly, but, prompted (and translated) by his doting family, he was able to communicate and answer questions. His words were emotional and heartfelt. At times he laughed until he cried, especially when Keith John, clowning around, got down on his knees, pretending to be Willie, and sang, or when the John brothers would vocalize on a Four Tops song to tease him.

“I just loved him,” Levi said of Willie. What he most admired about his vocal talent was that while improvising, off on a dazzling, horn-like solo, Willie would never get “caught up,” never lose his place. “He was just a great singer. He could sing anything,” Levi said. What was his favorite song of Willie’s? “All of them!” he said, laughing.

When conversation turned to Willie’s stint at the Moore School, Levi blurted out, “I went to Moore School! Yep...”

“But weren’t you the good boy, while Willie was bad?” Kevin John said.

“That’s what EJ always said.” Levi just smiled.

Phil Townsend knew better, he grew up with both Levi and Willie. “We were all rascals.”

2

NO BLUES IN THIS HOUSE

By the 1950s, jazz had become an esoteric, uptown sort of music. It was the blues that percolated through the black neighborhoods, outselling jazz records by a fair measure, much to the chagrin of record store owner Berry Gordy Jr. His 3-D Record Mart went under in the early 1950s because Gordy had overestimated the city’s demand for jazz, and underestimated their love for the blues. It was a lesson the budding entrepreneur never forgot—later, at Motown, he produced pop music teenagers loved, not the jazz or blues he would have preferred.

The blues were not yet constricted by sub-genre classifications such as Chicago blues, or electric guitar rock infused with blues, or folk-blues sung by geezers in denim overalls. In the 1940s and 50s people said “the blues” when talking about rhythm & blues, jump blues—anything with a pulse. In the black community, people would dress up in their best clothes and go out to dance in the evenings, it was a vital part of life.

Lillie John loved the blues, but her mother wouldn’t let her sing that way when she was growing up in Louisiana. When she became the matriarch of her own home, Lillie John enforced the same musical decorum that she knew growing up: no blues. She did make one exception, though. On the day she married Mertis John, Lillie sang him a love song. Then Lillie put the blues away for good. “She just carried it in her heart,” daughter Mable said. “She loved the sound of the blues.”

Growing up, Willie John heard the blues. He sang the blues. But it took B.B. King to bring the blues back into the John house. During the early 1950s, the record bus would come to Cardboard Valley from time to time. The bus was fitted out with a record player, speakers and boxes of brittle shellac 78s, driving through the neighborhoods of Detroit, broadcasting the hits of the day to entice residents to buy records. If the music peddlers were lucky, they’d get someone happy enough—and flush enough—to buy a record player, too.

The record bus was driving through the north end one day in 1953, playing B.B. King’s bluesy ballad “Darlin’ You Know I Love You.” When Lillie John heard B.B. King crooning to his darling, “She told my father that she heard this song that identified exactly how she felt about him,” Mable said. “My father, like all men, was so proud, thinking, ‘My wife hears a song that identifies me to her.’ So my father went out to that bus and bought that record. We didn’t have anything to play it on, so he bought the Victrola too, and that was the first blues song that ever came into our home.” Well, that was the first blues song that officially came into the John home, anyway. Unofficially, Willie and his siblings tuned the radio to blues, pop, jazz and country when their parents were out of earshot, and sang softly in their beds at night. Or they’d take a short bus ride to Joe’s Record Shop down on Hastings, to hear the latest records blasting from the loudspeakers.

Though she was strict, Lillie didn’t object to her children’s passion for music. She started her brood singing at the Triumph Church in the early 1940s, gradually adding each child as they became old enough to perform. Brother Mertis describes the sequence of events: “First we started doing Bible things. We had a little thing where our pastor would ask us biblical questions. Then I began to sing, then Mable. Mable liked to talk a lot, she kept doing her talking thing. The next child came along and we were singing together. Then the next one came, she added him. The next one came, she added him. Then Willie came, she added him. We would go from church to church, singing.”

In 1944, when six year-old Willie pestered his way into the family troupe, Lillie named them the United Five. It was here that Willie found his voice, singing church songs to the rumble of the Hammond organ, answered by the cries of the congregation with their paper fans fluttering in the swelter of the Detroit summertime. Willie would close his eyes and sing “Jesus Met The Woman at the Well,” as the women in the front row threw hats and money at him, crying, “Sing, son!” And Willie sang, “He said woman, woman... where is your husband?” with his eyes closed, as if in a trance. At the end of the song he was still so engrossed in the music that Willie’s impatient siblings would have to pinch him and yank him by the arm when it was time to leave. Singing like that, eliciting such riotous behavior in church ladies, unleashed Willie’s passion for song. As Willie said, “I’ve been singing ever since—morning, noon and night.”

The United Five didn’t just sing at Lillie’s home church, but at churches all over the east side. They sang on programs with the Dixie Hummingbirds, the Mighty Clouds of Joy and with Sam Cooke, when he was leading the Soul Stirrers. “And we were kids!” Mable said. “But Willie was so in tune and so addicted to music, the blues... and he could learn songs so fast.” A church friend of Lillie’s, Laura Pickens, convinced Lillie and Mertis Sr that she could open doors in the music business for their children, and she started promoting the group. Pickens took the kids to watch Sugar Chile Robinson and learn from the piano-pounding seven year-old who had a national hit with “Numbers Boogie.” She also booked the United Five into Detroit’s most exclusive hotel, the Book Cadillac.

“Black people could not go in that hotel, I’ll tell you, but they wanted the John family in the hotel,” Mertis Jr said. “So we went to sing there.” Willie said that it was 1948 when his family sang at the Book Cadillac, which means he was just ten or 11 years old.

Despite the early demand for Willie’s voice, gospel couldn’t contain the young singer, though the spirit and intensity of church music would always be part of the primal DNA of his voice. No matter how Lillie tried, she couldn’t control what her children heard on the radio, or what they were exposed to while they were running on the streets. “I heard Charlie Parker when I was eight,” EJ bragged. Like his brother, Willie would have been exposed to the cool, modern sound of bebop jazz that mingled with the more popular blues in the neighborhoods.

The Paradise Theater on Woodward was where the top tier of black jazz artists played in the 1940s. The theatre was home to the Detroit Symphony and called Orchestra Hall until 1941 when the symphony moved on to a new home. The venue was repurposed and renamed after Paradise Valley, the black entertainment district east of Woodward. For years, the Paradise Theater was where black Detroiters—and music-loving whites—went to see the best in black entertainment. Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Count Basie played week long engagements at the Paradise to packed audiences. Just as popular were the Thursday amateur nights. “All the like-to-bes and want-to-bes, as singers and performers, they would allow them to sing,” Mable recalled.

Willie knew he had to be there. He wasn’t old enough, but that wasn’t going to stop him. At home, his brothers would watch as Willie worked the crossword puzzle in the newspaper, then turned to the entertainment ads to see who was in town. “He’d use that to plan where he’d sneak out and go that night,” said Raymond. Maybe it would be Count Basie at the Paradise Theater, or Paul Williams at the Warfield Theater on Hastings—whoever it was, Willie meant to go see them perform.

Hastings Street was Detroit’s avenue of sin, with its hookers and grifters, and the smoky jazz drifting out of nightclubs like the Club Three Sixes and Sportree’s. The smell of beef sizzling on the grill at Tip Top Hamburgers was as alluring as Della Reese’s dusky alto crooning “In the Still of the Night” from the jukebox. It was all too tempting for Willie. Hastings Street and all it had to offer was a bit far to walk from Cardboard Valley, but Willie had already gamed that. He learned from watching a blind friend that if the conductors were convinced he was sightless, he could ride the DSR buses for free.

“All the bad people lived on the east side,” Berry Gordy Jr once remarked. Good and bad lived on adjacent corners, at least. Aretha Franklin’s father’s church, The New Bethel Baptist Church, was in a converted bowling alley on Hastings, just steps away from the hustlers and ladies of the evening. Singer Wilson Pickett’s father’s house backed up on to Hastings, and Pickett remembers looking out of his father’s backyard onto the strip, shivering at the thought of it decades later. “It was a dangerous place,” Pickett said.

Nonsense, said Norman Thrasher. Growing up, he loved the hurly burly of Hastings Street. He was either walking down the street singing (“Everybody would say, here comes Norman!”) or harmonizing on the streetcar. Before he was old enough to gain entrance, Thrasher would stand outside Sunnie Wilson’s Forest Club, straining to hear balladeer Herb Lanz sing. Detroit had everything, and the north end was bursting with things to do. “Everything you could want in the entertainment business,” Thrasher said. “And Hastings is where everything was. You found people on Hastings who would give you advice that you couldn’t find at home. Old men would talk to youngsters to make them mind when they went back home.” Mack ‘Mustang Sally’ Rice saw the lower element of Hastings Street as a financial opportunity. Rice would borrow his father’s car, drive down to Hastings and charge the junkies for rides. “I’d follow them into these big apartment buildings to get paid, I didn’t want them running off with the money they owed me.”