Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

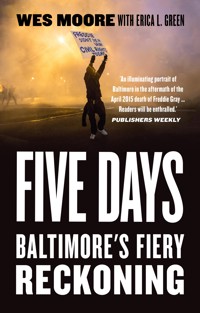

'An illuminating portrait of Baltimore ... Readers will be enthralled' Publishers Weekly A kaleidoscopic account of five days in the life of a city on the edge, told through eight characters on the front lines of the uprising that overtook Baltimore and riveted the world. When Freddie Gray was arrested for possessing an 'illegal knife' in April 2015, he was, by eyewitness accounts that video evidence later confirmed, treated 'roughly' as police loaded him into a vehicle. By the end of his trip in the police van, Gray was in a coma from which he would never recover. In the wake of a long history of police abuse in Baltimore, this killing felt like the final straw - it led to a week of protests empowered by the Black Lives Matter movement, then five days described alternately as a riot or an uprising. New York Times bestselling author Wes Moore tells the story of the five days through his own observations and through the eyes of other Baltimoreans: Partee, a conflicted black captain of the Baltimore Police Department; Jenny, a young white public defender who's drawn into the violent centre of the uprising herself; Tawanda, a young black woman who'd spent a lonely year protesting the killing of her own brother by police; and John Angelos, scion of the city's most powerful family and executive vice president of the Baltimore Orioles, who had to make choices of conscience he'd never before confronted. Each shifting point of view contributes to an engrossing, cacophonous account of a moment in history with striking resemblances to far more recent events, which is also an essential cri de coeur about the deeper causes of the violence and the small seeds of hope planted in its aftermath.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 368

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

v

To Mia, James, and all of the children of Baltimore.

I believe in you. And we will do better.vi

Contents

Prologue

Isat in the farthest pew from the front in a Baltimore chapel, staring at the flawless ivory-colored casket of a twenty-five-year-old man. Afraid to go any closer. Wondering why I was even this close. High above his casket on the back wall of the chapel, the words “Black Lives Matter” were projected onto a screen, as if the aspirational slogan and the body below were not statements in violent contradiction.

It was the morning of Monday, April 27, 2015, and I was at Freddie Gray’s funeral. Three weeks earlier, on April 12, 2015, a police officer on a bicycle had made eye contact with the still-living Freddie Gray, a young man from the Sandtown-Winchester/Harlem Park section of Baltimore—the “wrong side” of Baltimore, a neighborhood where life expectancy was not quite sixty-five years, a full seven years shorter than in the rest of Baltimore and around the same as someone living in North Korea. Gray met the officer’s eyes and ran. The officer gave chase, soon joined by two others, and soon Gray was captured. The police searched him, and when they found a pocketknife in his pocket, they arrested him. When he couldn’t, viiior wouldn’t, walk to their transport van, they dragged him along the sidewalk. What happened next was a matter of dispute. But when Freddie Gray died a week later, from a severed spine, much of Baltimore believed the police had killed him.

That belief didn’t come out of nowhere. What was life like if you grew up like Freddie Gray? The fear of being a victim of police brutality was ever present if you were young and black in Baltimore—just one more trial for kids who already carried the mental anguish and physical adversity of growing up in chronically neglected neighborhoods. You knew neighbors, cousins, uncles, aunties, and friends who’d been victims of random or targeted violence. The violence was physical but correlated with the emotional violence that was often its cause or consequence. And the violence was pervasive, a factor in every decision you made—which streets you walked down, what time you started and ended your day, whom you trusted. The most quotidian decisions were shaped by structurally determined abnormalities. You called it life.

In that chaos, you feel a need to rely on the institutions that supposedly are in place to support you and your family: your school, your place of worship, your city government, your fire department, your police department. The individuals who make up these institutions pledged to uphold your best interests and safety, to protect and serve. But what happens when those pledges are broken, when those institutions break down? What happens when it no longer feels like the schools are deepening your education or preparing you for work? What happens when houses of worship feel void of spirituality and unresponsive to your everyday needs? What happens when your political representatives seem to be more concerned with ixthe interests of the wealthy and already powerful and are careless or contemptuous in the face of genuine human pain and distress? And what happens when the people who are paid to protect you are your predators? Your institutions of support become your captors. Your saviors become your jailers.

Freddie Gray and so many other boys like him grew up in the type of poverty that permeates everything: how you are educated, the water you drink, the home you live in, the air you breathe, the school you spend most of your day in, the way you are policed, whether or not you will die in the same poverty you were born in. It was that poverty that raised the probability that Freddie would be exactly where he was on April 12, 2015, and then again on April 27, 2015. In fact, the odds started being stacked against Freddie generations before he was born.

Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren released a report right before Freddie Gray was arrested for the final time. The report compiled years of research on the best and worst places in America for young children born into poverty to grow up. Many of the best places were in the DMV area—the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia—including Montgomery County, Maryland, a jurisdiction that hugs the nation’s capital and consistently has the highest-rated schools in the state of Maryland. Montgomery County is also a little more than twenty-five miles from the jurisdiction that Chetty and Hendren reported as the worst place in the country to be born poor: the city of Baltimore, Freddie Gray’s place of birth.

For every year of his life spent in Baltimore, the report stated, a poor boy’s earnings as an adult would fall by 1.5 percent. When you factor that in for an entire childhood and early adulthood, the average twenty-six-year-old man who grew up xpoor in Baltimore would earn about 28 percent less than if he grew up anywhere else in the country. But why?

It’s not an accident. Poverty is so concentrated because it is generational and, research shows, created with relentless intention. Redlining, predatory lending and discriminatory covenants, blockbusting, and forced segregation all constrained opportunities and cut off pathways to increased material and social capital for generations of black Baltimoreans. Transportation lines were drawn to prevent these communities’ access to jobs and services—and, just as importantly, to keep the haves and have-nots separated. Underfunded and poorly managed schools failed to serve as engines of economic mobility for families. Talented teachers and administrators were provided greater incentives to move on than to stay on. The same applied to students, who dropped out at alarming rates—and even the ones who graduated from a Baltimore high school did so largely unprepared for higher education or employment.

I am from Baltimore but run the largest poverty-fighting organization in New York City—one of the largest in the country. I spend a great deal of time in economically distressed communities in New York: Brownsville, East New York, the South Bronx. These places are nationally known, statistically and anecdotally, for their significant challenges when it comes to creating true and sustainable economic mobility. New York in no way has poverty defeated. The life expectancy in Brownsville, Brooklyn, is seven years shorter than the average life expectancy in the city as a whole. The South Bronx neighborhoods of Mott Haven and Melrose have three times as many hospitalizations for asthma as the rest of the city. But the truth is I would rather be born poor in New York than in Baltimore.

That morning in April, when we gathered to lay Freddie Gray to rest, protests in Baltimore surrounding his killing had xibeen going on for weeks and showed no signs of quieting; in fact, they seemed to be gaining in intensity. The silence from the police department and elected officials in the face of Freddie’s suspicious death was met by screams from the other side, demanding answers and accountability.

The funeral took place on a clear spring day in Baltimore. Just forty-eight hours before, the city had erupted in violence and vandalism. So, as they prepared to bury Freddie, elected officials and the Gray family asked for peace. Congressman Elijah Cummings, who represented the 7th Congressional District in Baltimore, Freddie Gray’s home district, made this plea before the funeral: “I haven’t come here to ask you to respect the wishes of the family. I’ve come here to beg you.”

I arrived early to the New Shiloh Baptist Church, early enough that there were only hundreds of people there, not the thousands who would eventually converge on the church that morning. I hadn’t been to New Shiloh in years, but it was the church I’d attended back when I was a student. I’d walked its center aisle on the day the senior pastor invited visitors who were looking for a church home to come forward, a cherished ritual in the black church tradition. As I walked down the aisle that day—along with a half dozen other new members—people cheered, prayed, and clapped. The church community saw our journey down that aisle as proof of the potency and durability of Jesus’s message of liberation. On this day thousands more would walk down that aisle, not to give their lives to a higher purpose but to remember a life that had been taken away.

I didn’t join the procession to pay respects but watched the community as it poured down that aisle. Some men and women were in T-shirts, others in mourning black. The politicians began to arrive, a who’s who of Baltimore political power xiiwalking into the sanctuary and proceeding down the aisle toward the open casket. I sat in the back, conflicted about whether my presence there was meaningful or right. I wanted to pay my respects, but I didn’t feel I deserved to take that walk. I have attended many funerals in my life. Funerals of family and friends and siblings of friends from my old neighborhood. Battlefield funerals in Afghanistan and stateside remembrances of soldiers who paid the highest price. But this was the first funeral I had ever attended of someone I didn’t know in life—someone whose name I didn’t even know until his death. And that was the problem.

While Gray’s premature death touched me deeply, what I was coming to know of his life bothered me more. We had come from similar places, but I had been so fortunate, so blessed. So lucky. I had a mom who didn’t understand “no” and who had creative resources around her that helped keep our family afloat and on the move. I was lucky that my run-ins with law enforcement at a young age weren’t fatal or traumatizing. Lucky that I was given the opportunity to have second chances. Our family had ambition and were wildly opportunistic when openings appeared—but luck and circumstance were on our side, too.

In the back of that sanctuary, I pondered the details I knew of Freddie’s life. I’d learned that he had been poisoned by lead as a toddler: his family was part of a lawsuit against a property owner over Freddie and his siblings’ exposure to unsafe levels of lead, a neurotoxin that causes damage to the brain in many ways, from learning disabilities to a propensity for aggression. Five micrograms of lead in a deciliter of blood is the point at which negative impacts are predicted. Thirty-six micrograms were found in Freddie’s blood. These children—including Freddie—were born into homes and neighborhoods that were xiiiliterally making them sick. He never held a legal job for long and had done time for petty crimes. The officers who arrested him that April day knew him by name.

Sitting in the back of the chapel, I meditated on his painful life—or what I knew of it—and its painful end. And I prayed for his family, who were weathering public scrutiny after having become national symbols of police violence, a position they weren’t prepared for. Then I sat looking around the church at all the civic leaders beginning to gather near the sanctuary’s pulpit. Was this just theater? Or would this solemn gathering effect change on a scale that was commensurate with the loss—the losses—we were marking? Did we even know what that kind of change would look like?

I left before the eulogy, the soaring speeches, and the tear-jerking remembrances. I had to catch a flight to Boston for a speech I was giving—on poverty. I was thirty thousand feet in the air when it became clear to the world that the funeral would not be the big news of the day. The city I called home, the city that had helped raise me, was about to come under siege.

I had been invited to Boston not just because I was at the time directing an anti-poverty educational organization that I founded, but because of my own life history: after being raised by a single mother and coming of age in Baltimore and the Bronx, I was being presented as a “success story.” My story let people believe that individual effort could overcome obstacles, so they wouldn’t have to think too hard about the systems, structures, and policies that make stories like mine so rare. I was starting to realize that basking in this kind of celebration was its own kind of problem—that it made me complicit in a xivkind of blindness. I was thinking about all of this while hurtling toward Boston at thirty thousand feet, but I didn’t realize just how far removed from the ground I was.

Before I got off the plane, back in Baltimore things had escalated. It was during those few hours that young people and police faced off at Mondawmin Mall, rocks flew, and officers were hurt. Mondawmin Mall, a three-level shopping center, sits in the heart of West Baltimore. It was also a central transportation hub, and that became part of the story later in the afternoon, when buses and trains in and around Mondawmin were shut down by the city; many people blamed that action for the escalation in violence that followed. By the time my plane landed in Boston, my voicemail was full of frantic calls from friends and family and requests from media colleagues to come on the air and talk about what was happening in our city. I went to my hotel and sat up most of the night talking to loved ones and watching cable news, piecing together as best I could what was happening.

When I was four, my father died in front of me in our Maryland home. Afterward, we moved to the Bronx and lived with my grandparents on crack-plagued and police-harassed streets in a neighborhood that many felt had intentionally been allowed to descend into squalor and chaos. The Bronx helped to shape me and build me. By the time I was eleven I knew the feeling of handcuffs on my wrists. By thirteen I had been placed on academic and disciplinary probation at my school.

My mother had eventually found a good job in New York—the first job that had ever given her full benefits (life and health insurance as well as retirement), the first job that paid her enough that she didn’t need a second one to raise her three xvchildren, the first job that would give her regular hours. The Annie E. Casey Foundation is one of the nation’s largest philanthropies with a focus on children, with close to $1 billion in assets. The endowment was established by one of the founders of United Parcel Service and named after his mother. When my mother got a job there, the foundation was headquartered in Greenwich, Connecticut, an affluent enclave outside of New York City, and she commuted an hour and a half each way. But two years after she was hired, the organization’s board decided to move to an area that more closely aligned with the work they were focusing on. They chose to move to Baltimore. And when I was thirteen years old, so did my family.

As a teenager, I remember playing basketball at Druid Hill Park and learning that nobody called fouls. Hearing life lessons at the barbershop on Saratoga Street while the buzz of clippers shaped up my neck and sideburns. Scraping my knee while trying to show off for girls at Shake & Bake, a West Baltimore roller rink that protected kids inside it from the violence and neglect outside it. I didn’t romanticize Baltimore. I knew that the city’s problems paralleled much of the chaos I’d experienced in the Bronx—decaying infrastructure, failing schools, a drug epidemic that held the population in a vicious chokehold—but I still loved it. I spent my high school years in military school in Pennsylvania and joined the army right after high school. I graduated from junior college and then received my four-year degree back in Baltimore. During all those years, all those transitions, Baltimore was where I went back to when I was looking for a place to call home.

After college I left Baltimore again. I lived in Oxford, England, as a graduate student and in Afghanistan as a paratrooper in the US Army. I worked in Washington as a White House Fellow, and in New York as an investment banker. xviThings were going well for me and my family—we lived comfortably in Manhattan. And then in 2013 I left finance to create a new organization to help bring college education to those for whom it seems out of reach. My wife and I decided to pursue those new dreams in my old hometown, Baltimore. Friends in both New York and Baltimore questioned my decision. Was my mom sick? Had I been fired? My answer was simple: I wanted to come home.

As I sat in that Boston hotel room and watched my city descend into a state of emergency, I experienced a strange feeling. I felt guilty being away, but it wasn’t just that. An audience in Boston would listen to me talk about poverty, but at a historic moment in my own city’s history, I was MIA. It felt symbolic of something deeper, and it troubled me.

I got home from my travels on Wednesday, April 29, almost exactly forty-eight hours after the uprising kicked off. As I drove through downtown, it was eerily quiet. National Guard troops were deployed forty deep outside City Hall, which was two blocks away from a police station, making it by far the safest place in the entire city. I imagined what it must have been like for those soldiers. I remembered wearing that same uniform: “full battle rattle,” we called it. You join the Guard expecting to be called to address natural disasters such as floods or hurricanes. Perhaps you’ll be deployed to augment the armed forces during times of war. But the other function of the National Guard has been to serve as a patch for the unaddressed wounds of racial tension and economic disillusionment. Of the twelve times in our country’s history that the president of the United States has called in the National Guard, xviionly twice was racial conflict not involved: the 1970 postal workers’ strike in New York and the looting after Hurricane Hugo on the island of St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands in 1989. The other occasions: the desegregation of a Little Rock schoolhouse in 1957, the integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962, the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963, the integration of Alabama schools in 1963, the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march in 1965, the Detroit riots of 1967, the riots in Chicago, Washington, and Baltimore after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and the Los Angeles riots in 1992 after the Rodney King verdict.

The vast majority of the soldiers stationed near City Hall that day were not from Baltimore itself. For many, the only experience they’d previously had of Baltimore was going to see the Orioles play down at Camden Yards or maybe taking a field trip to the aquarium as a schoolkid. I remembered my own time as a soldier and what it was like patrolling areas that you were not familiar with. In Afghanistan, we patrolled communities that were understandably skeptical of us and our intentions. I tried to read and learn as much as I could about the spaces I was about to enter. But all the reading in the world didn’t prepare me for what we faced, the burden of history reflected in the faces of the people we encountered. A history of foreigners arriving with conquest on their minds. A history of meeting those invaders with contempt, skepticism, fear, and resistance. And it was all justified. I walked into their neighborhoods loaded down with weapons and protective gear, a stranger from a distant land, and asked them to trust us, insisting we were there to help them. But the truth was that the people we encountered had rational reasons for their skepticism, and we’d been sent there to do an impossible job. I passed xviiimy brothers and sisters in uniform on the steps of City Hall and empathized as they stood watch over my brothers and sisters in our communities in Baltimore.

After stopping to check on my wife and kids, I went straight to church. At Bethel AME in West Baltimore, five minutes from where Freddie Gray had lived and died, a meeting was just starting, led by the church’s pastor, Dr. Frank Reid. Dr. Reid has loomed large in my life since my return to Baltimore. Like many ministers in black communities, he does more than teach the Word: he advises, consoles, advocates, and inspires hope in communities where hope is not generously allocated. His grace and knowledge of not only God’s word but earthly realities inspire me. We had spoken a few times over the previous few days, and he had asked me to stop by the church. When I got there, a hundred local pastors, gang leaders, and community members had gathered in Bethel’s soaring sanctuary. Dr. Reid looked tired. You could probably count on the fingers of two hands the hours of sleep he had gotten over the past few days. He asked me to say a few words, and I stood self-consciously, still in sweatpants from the plane.

I told the gathering about something that had happened as I stood in a crowd at the airport watching CNN loop footage of buildings burning, knowing that this was happening in my own hometown. Suddenly a stranger near me, in khakis and a polo shirt, spat out: “Baltimore.” I could tell from his scornful tone he wasn’t from there.

I couldn’t say I’d never complained about Baltimore; griping about your hometown can feel like a bit of a pastime. Baltimoreans have mastered it. We can spend hours in a bar or barbershop railing about how badly the city is doing. But then we pay our tab and head back to our homes and communities. Our tax dollars—and our abiding love for the place—pay for xixthe right to complain about everything. But when outsiders complain, we take real issue with it.

Speaking to the crowd at Bethel, I tried to turn the stranger’s contempt into a galvanizing moment, a rallying cry against apathy. When I was done, the assembled crowd merely clapped politely. Frustration and feelings of inadequacy overtook me again. When I looked out into the eyes of the people sitting in the pews, I realized why the response to my abbreviated speech had been so muted: many of the people there questioned what aspects of the city should be saved at all. On streets all around us, I knew, it was hard to tell which of the wrecked stores and rowhouses had been looted or burned that week and which had been falling apart for decades. Our meeting had to end within the hour, so that people could get home before the 10:00 p.m. citywide curfew that had been instituted the day after the National Guard showed up. Sitting with me in that sanctuary were street leaders who might be dead within the year. The life I was living and the future I dreamed about were unreachable for most of them.

This book is about more than Freddie Gray’s death and its aftermath. This book is about more than Baltimore. It’s about privilege, history, entitlement, greed, and pain. And complicity. Mine. All of ours.

Over the last few years I’ve returned to the story of those five days in Baltimore again and again, trying to understand the events at a human scale—what triggered the uprising, who was drawn into it on all sides, what motivated them. But it all started with questions that bubbled up in those first moments and have haunted me ever since: How much pain are we willing to tolerate in others? How much fear, death, and hopelessness xx will we accept when they fall on our neighbors? What can we learn from the people who throw themselves into the breach—those among us who stop looking away and give something, maybe even everything, to try to repair those gaps, to heal those wounds? And what do we learn from their failure?

Five Days will span the most dramatic period of the unrest, April 25–29, 2015. I spoke to people at all levels of the city’s life, but seven lives stood out—an activist, a businessman, a cop, a basketball star turned rioter, a business manager and community protector, a fledgling politician, and a public defender. Their lives intersected at key moments, and taken together, their stories reveal a truer, fuller, and more surprising version of events and their context than what the media was able to show at the time. Their narratives tell a larger story about what happens when a city wakes to find the American dream is exactly that—an unconscious state that contains shades of reality but is ultimately unmoored from it. Woven together, their stories offer a true and kaleidoscopic vision of pain and redemption on the ground.

When my mind goes back to the day of Freddie Gray’s funeral, I remember looking at his casket from the back of New Shiloh Baptist Church, Freddie’s perfectly white shoes peeking out, pointing toward the heavens. My mind retreats to Nina Simone. Her rendition of the song “Baltimore” was as haunting in 2015 as it had been when she recorded it in 1978, the year of my birth. Nina Simone’s torching voice entered over the distinctly reggae-drawn concoction of steel drums and bass guitars driving the steady, swaying beat. The melodic pulse was overpowered by the melancholy lyrics and unforgettable force of Nina Simone’s roar. Listening to the song, you can imagine the high priestess of soul, eyes closed, gripping xxithe microphone, singing her pain into a space that was occupied by too many.

Oh, Baltimore

Ain’t it hard just to live

Just to livexxii

Timeline: Before the Five Days

1989

Gloria Darden gives birth to twins, a boy and a girl. The twins are born two months premature. In her early twenties when she had the twins, Gloria had never attended high school. She could not read or write, and struggled with heroin addiction. Tiny and underweight, Freddie and his twin sister, Fredericka, spend their first months in the hospital. After five months, Gloria brings the twins back to the housing projects of West Baltimore.

1992

Freddie and his family move to 1459 N. Carey in West Baltimore. The home rents for $300 a month. In 2009, it and 480 homes just like it will be named in a civil suit regarding the endemic levels of lead paint throughout those houses. By age two, Freddie and his twin sister have elevated levels of lead in their blood and suffer lasting brain damage. The family lives on Carey Street until the twins are six years old. xxiv

1995

Freddie starts school at Matthew A. Henson Elementary School in Sandtown-Winchester. Because of the lead poisoning, Freddie’s behavior poses considerable challenges to the school’s teachers (statistically, among the least-experienced and worst-equipped educators in Baltimore City). His teachers enrolled Freddie in special education classes, which he would never leave. By the fifth grade, Freddie was four grade levels behind in reading. Driven out of the classroom by his intellectual disability, Freddie spends his early years in nearby recreation centers.

1998

Freddie is spending more and more time out of the classroom, experiencing increasingly long stretches out of school. Freddie starts to migrate to the corners and begins dealing drugs. At home, Freddie’s stepfather leaves for drug rehab because of his heroin addiction. Without his income, Freddie’s home experiences long stretches without electricity or running water. Freddie’s godmother takes Freddie to church, where he volunteers delivering meals to senior citizens and washing cars.

2008

The Baltimore City Public Schools record Freddie’s last attendance in school. He’s eighteen. He’s in the tenth grade.

2009

Freddie is arrested and sentenced to four years in prison for two counts of drug possession with intent to distribute.

2011

Freddie is paroled and back on the streets. xxv

2013

Freddie is arrested again for drug possession and distribution. Shortly thereafter, Freddie’s half brother, Raymond Lee Gordon, thirty-one years old, is gunned down near the Inner Harbor in downtown Baltimore.

APRIL 12, 2015

8:39 a.m.

At the intersection of W. North Avenue and N. Mount Street, four officers on bicycles attempt to stop Freddie Gray and another man who ran after making eye contact with the police.

8:40 a.m.

Police catch and arrest Freddie on the 1700 block of Presbury Street. According to police accounts, the arrest takes place without incident and no force is required.

8:42 a.m.

A police van is requested to take Freddie to the police station. At that point Freddie indicates he has asthma and asks for an inhaler. Minutes later when the van arrives, Freddie is put into leg irons and placed in the back of the van.

8:59 a.m.

At Druid Hill Avenue and Dolphin Street, the van driver requests a secondary unit to drive over and check on Freddie in the back of the van. Minutes later, the van Freddie is riding in is requested to go to 1600 North Avenue to pick up another recently arrested individual. There is some communication between the police officers and Freddie, and his behavior and physical condition seem off, enough so that the officers will later admit there was concern at that point that they “needed to assess Mr. Gray’s condition, how we responded, were we able to act accordingly.” After the xxvistop, the van eventually continues to the Western District police station with both suspects.

9:26 a.m.

The city fire department responds to a call for paramedics to support an “unconscious male” at the Western District police station.

9:33 a.m.

The medics arrive and provide “patient care” for Freddie for twenty-one minutes.

9:54 a.m.

The medics depart with Freddie Gray for the Shock Trauma Center at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

APRIL 14, 2015

Freddie undergoes double surgery at Shock Trauma. It is determined that Freddie has three broken vertebrae and an injured voice box.

APRIL 15, 2015

Freddie remains in a coma.

APRIL 18, 2015

Word spreads about what happened to Freddie, and protests begin outside the Western District police station.

APRIL 19, 2015

At seven o’clock in the morning, Freddie is declared dead at Shock Trauma.

SATURDAY, APRIL 25

Tawanda

Tawanda Jones had been waiting two years to join this march for justice. Well, not exactly this march—it was not for her brother but for another black man from the opposite side of town—but at the end of the day, she decided, any black man is every black man. Freddie Gray’s death a week ago had breathed new life into the cases of others who had come before him, including Tawanda’s brother, Tyrone West.

Two years on from her brother’s death, Tawanda felt like everyone else had forgotten the one thing she knew she’d never get out of her mind: the July day his body had lain on the sidewalk, drenched in pepper spray from the violent arrest the police said he deserved.

There were two unreconcilable sides to the story: what the police said and what she knew in her heart. Their story: Her brother, a black man, large and hostile, had refused to follow orders and then struggled with them. They said that he was dehydrated and had a heart condition and died in the struggle. Her story: Her brother was murdered.

She had been screaming her story into microphones and 4bullhorns every week for nearly one hundred weeks, in winter and summer, rain and sleet, armed only with posters of her gentle brother’s face, his eyes pleading to the crowd to pay attention. For more than seven hundred days she had been taking her cause to the corners. Sometimes she was with whatever small group she could assemble—family, friends, occasionally strangers with gripes of their own. Sometimes she was alone, shouting into the Baltimore sky.

NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE.

ONE MAN, UNARMED.

JUSTICE FOR TYRONE WEST.

She called the protests “West Wednesdays.” It had a ring to it. The news liked catchy slogans. And reporters from all the news outlets were going to be here today.

Tawanda had been asked by Freddie Gray’s family to help lead the protest from Gilmor Homes, the housing project in West Baltimore where Freddie had been arrested, to City Hall. They knew about her commitment not just to her brother but also, beyond her own heartbreak, to the larger cause of addressing police violence and accountability. They respected her—the hours and days she’d already put into this work—and wanted her to stand with them. It was going to be the big protest to cap all the others that had sparked in the last week, ever since the news broke that the twenty-five-year-old would not survive the break in his spine.

She had watched all the shaky cellphone videos of Gray being dragged by the police, and Tawanda felt her soul pierced every time she heard his screams blare from the television—not just in sympathy for Gray but for herself, for she wished 5she had gotten to hear her brother’s voice, even his screams, in his last seconds. But the videos were followed by a familiar script on the newscasts, one Tawanda recognized too well: Black male. Encounter with police. Dead.

Tawanda had met Freddie’s mother, Gloria, at a protest exactly one week before the big march, while her son still lay in a coma at Shock Trauma. Tawanda was eager to give the Gray family something she had not been afforded after Tyrone’s encounter with the police: hope.

“Don’t give up hope,” she told Freddie’s mother. “He’s going to pull through. I’m going to be praying for your son.”

The following day, a Sunday, Freddie was pronounced dead.

When Tawanda heard the news, she was heartbroken, thinking over and over again about the moment the day before when she’d tried to console Freddie’s mother, and for a moment Gloria had looked into her eyes with a flicker of hope. Tawanda decided then and there to dedicate the next West Wednesday, held outside the Western District Police Station, to Freddie.

There had never been any citywide marches for Tyrone. But after Freddie died, the protests persisted for days, and Tawanda watched as the city was roiled by protesters shouting the very thing she’d been screaming out every Wednesday for two years: that the Baltimore Police Department was the biggest gang in America, with a license to kill with impunity.

In the months and years prior to Freddie’s death, young men with similar profiles had met similar fates. In 2012, Anthony Anderson was walking in his neighborhood on his way to his East Baltimore home when he was confronted by the police, who ordered him to stop moving. He “failed to respond” to commands and was tackled by a police officer. That tackle—or, as the Board of Estimates called it, a “bear-hug maneuver”—left Anthony Anderson’s spleen ruptured and his 6ribs fractured. The internal bleeding killed him shortly after he arrived at the hospital. Initially investigators said Anderson died because he choked on drugs he was trying to hide from officers, but the medical examiner’s report dismissed that claim, instead pinning the blame on Anthony’s entire body weight slamming onto his neck and collarbone. The Anderson family was awarded $300,000 by the city of Baltimore. Even though the state medical examiner determined that he died by homicide, no officers were charged in his death.

Tyrone West had an altercation with law enforcement after a traffic stop in Northeast Baltimore. He was unarmed, and the state claimed his death was due to the heat of the day and a heart condition. Once again the city and state eventually dispensed of the matter through a civil settlement, paying Tyrone’s three children $1 million. The details of these three cases were different, but they all have one crucial thing in common: despite the six-and seven-figure settlements, not a single officer was arrested, indicted, or found guilty of having any responsibility for the death of these unarmed African American boys and men.

The tension between law enforcement and the communities they were sworn to protect and serve had grown palpably thick in Baltimore. For many, the presence of police in the city’s black neighborhoods brought not a sense of peace or security but its opposite. The sound of a siren strikes a different pitch depending on which neighborhood hears it. Still, after the investigations and payouts, most of the community found a way to go on with their lives. Till the next one.

Tawanda didn’t go on with her life. For two years she held a lonely vigil demanding true accountability for her brother’s death. But now everything she’d been saying was being amplified 7 because of another death, and the world was watching. Maybe this time they would listen.

Still, though, all of the time she’d spent protesting, sometimes alone, had left her bruised. There had never been any marches for Tyrone. That still hurt, even as she looked for a good pair of shoes and prepared for the march of her life. She couldn’t deny that part of her felt stung at seeing so many people in the city finally preparing for battle, but on behalf of someone else. For her brother, there had been only a handful of witnesses who seemed to care enough to speak up and speak out.

Of course, there were reasons Freddie’s death was different, that it so quickly turned into a galvanizing moment instead of passing into painful silence like Tyrone’s. Portions of Freddie Gray’s final moments were caught on camera. Capturing video of police encounters is commonplace now, but Freddie’s death in 2015 coincided with the emergence of smartphones and social media as tools of citizen journalism. None of those other victims of police violence had images of their final moments, their bodies laid out on the concrete, broadcast to a global audience. Footage of police killings was starting to show up on people’s social media feeds raw, without being filtered through a controlled media narrative that adopted the police’s point of view and implied that the victims “deserved it.” Our generation would be the first to interact with violent death in this new way—through the same small window in our phones where we watched Eric Garner screaming “I can’t breathe” while an officer straddled his back, yanking him to the ground like a steer, or a young Tamir Rice standing in a park as a squad car pulled up and an officer fired his weapon into the child, ending his life, or Walter Scott in Charleston, South 8Carolina, being pulled over for a nonfunctioning brake light and soon after being shot in the back while fleeing, contradicting the officers’ sworn testimony. Complaints about violent policing could no longer be treated as folklore or dismissed as exaggerations. “Our word versus yours” is less of a stalemate—where the tie goes to the state—when there is video evidence.

The other exceptional factor in Freddie’s death was that it happened in the wake of so many other incidents between 2014 and 2016. The summer of 2015 was a bad one for police and community relations. According to The Guardian, in 2015 there were more than one hundred documented police killings of unarmed black people. All of these deaths were defended with different rationales and backstories, but the number is still staggering when you consider that each represents a case of an agent of the state using lethal violence against the accused—still innocent in the eyes of the law—who did not present an equal threat. Around that eighteen-month period alone, there was Mike Brown in Ferguson, Philando Castile in St. Paul, Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge. Each situation had its own particularities, but what they had in common was an obvious power imbalance that led to a death. In the aftermath of these killings, Freddie Gray’s death was less a data point than a tipping point.

A movement arose to meet this moment. After the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, the Black Lives Matter movement was launched by Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi, and their digital activism soon took on real-world form. By 2015, it was transitioning from a small group of disconnected activists to a global network with some forty chapters around the country, organized according to principles of distributed leadership and growing into a larger movement for black lives. By the time of Freddie’s death there was 9an articulated framework for response and mobilization when police violence struck. The growing protests were not driven purely by emotion. Even if the system’s response to Freddie’s life was chaotic and unfocused, the response to his death was, at least at first, strategic and organized.

For two years prior, as Tawanda held her own protests, most acted as if she were crazy. Police, politicians, and passersby gave her sympathetic looks and offered comforting words to her face, but she knew that behind her back they were asking: “When is she going to stop doing this?”

She had an answer for that: never.

John

John Angelos never really saw himself going into the baseball business. After graduating from the Gilman School, arguably Baltimore’s most prestigious independent preparatory school, and then Duke University, he went on to law school at the University of Baltimore, like his father, Peter. Law was the family business and his presumed career destiny. But in 1994, his father became the new owner of the hometown baseball franchise, the Baltimore Orioles, and wanted his sons, John and Louis, working in the business with him. Early on, John took on what he thought would be a temporary project. The Orioles were moving from seventy-five-year-old Memorial Stadium to a new park, Camden Yards, that would help anchor a rebuilt and reimagined downtown Baltimore.

Downtown Baltimore, bordered by its waterfront, used to be a collection of rat-filled docks where cargo ships came and went at a frenetic pace. Goods were traded, money was made. Not exactly a beauty at first glance, but there was a grace in its industriousness, a music in its cacophony of cultures and accents, foods and histories. Then, between 1958 and 1965, 11