11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

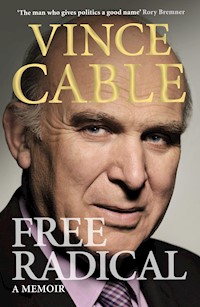

Today Vincent Cable is best known as 'the undisputed heavyweight champion of the credit crunch in Parliament' (Robert Peston), revered for his prescience and authority on the world economic crisis. But his journey to become Britain's most respected politician has been long, circuitous and sometimes very painful. In this memoir he tells that story for the first time. Free Radical is a candid book, written with wit and great insight. Vince Cable's life story is a long way from that of a conventional career politician. His book is as compelling as it is timely.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

FREE RADICAL

Vince Cable is Member of Parliament for Twickenham and has been the Liberal Democrats’ chief economic spokesperson since 2003, having previously served as Chief Economist for Shell from 1995 to 1997. He was elected Deputy Leader of the Liberal Democrats in March 2006 and was acting leader of the party prior to the election of Nick Clegg. His book on the economic crisis, The Storm, was published by Atlantic Books in 2009.

‘Vince Cable is a phenomenon of our troubled times … the most popular politician in Britain … a lone voice in a sea of complacency.’ Economist

‘Everything a politician should be and everything most politicians are not.’ Jeff Prestridge, Mail on Sunday

‘The undisputed heavyweight champion of the credit crunch in parliament’ Robert Peston

‘Vince Cable is the only politician to emerge from the credit crunch a star.’ Sunday Times

‘It is clear that Vince Cable is the rising star of the literary bunch.’ Kate Muir, The Times

‘The man who gives politicians a good name.’ Rory Bremner

ALSO BY VINCE CABLE

The Storm: The World Economic Crisis and What It Means

Copyright

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Vincent Cable, 2009

The moral right of Vincent Cable to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-848-87438-1

First eBook Edition: January 2010

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

Cover

FREE RADICAL

Also by Vince Cable

Copyright

Preface

1 Starting the Climb

2 You’ve Never Had It So Good

3 Ivory Towers

4 Olympia

5 Facing Mount Kenya

6 Red Clydeside

7 Latin Detours

8 A Passage to India

9 Big Oil

10 The Long March

11 Political Triumph and Personal Tragedy

12 New Millennium, New World

13 A Taste of Leadership

14 Fame, Fortune and Notoriety

15 Stormy Waters and Unfinished Business

Index

Preface

Books by politicians about themselves risk adding an extra layer of self-indulgence to careers already characterized by a talent for self-advertisement. Prime ministers and party leaders can be excused for publishing their memoirs and diaries since, even if, as is often the case, they are excruciatingly dull and painfully self-justifying, they contribute to the historical record.

The point at which less elevated politicians have anything useful to add is a matter for conjecture. But the piles of autobiographies and biographies of long-forgotten ministers and political personalities on second-hand bookstalls at charity fairs suggests to me that many of them failed to appreciate that they were well below that point.

There are, however, occasionally politicians of the second rank who produce work of genuine interest. Alan Clark’s wit, talent for racy gossip, and colourful sex life made for a fine book. I doubt that I could compete in any of those departments, however. A better model is Matthew Parris’s Chance Witness, a well-written and painfully honest book which sought to understand and explain the motives and circumstances which make and break a political career. I do not share the sexual orientation which he struggled to come to terms with, but recognize the crucial interplay of public life and private relationships.

Before deciding to write this document I have tried to clarify in my mind my motives. My main purpose is a modest and personal one: to explain to my children and grandchildren where I, and therefore they, come from. If I thereby interest a wider audience, that is a bonus.

I make no claims to absolute historical accuracy. The central characters, Olympia and my parents, are not here to answer back, and my parents, in particular, may feel that I could have given them a better write-up. There are omissions too: secrets of the kind that all of us carry to the grave. But this is a reasonably honest account of what made and motivated one moderately successful politician.

Chapter 1

Starting the Climb

York was once an industrial city. The factories that supplied the country’s railway carriages and fed its appetite for sweets have largely closed. They have joined the Roman ruins, Viking artefacts, and medieval walls and churches as monuments to a receding history.

I grew up when that history was still alive: breathing the delicious, all-pervasive smell of sugar, cocoa and vanilla; timing the day by the army of factory workers pedalling to and fro, announced by a swish of tyres and tinkling bells. My first home was a small terraced house close to the Terry’s factory where my mother and our neighbours produced chocolates. Far from resembling a dark satanic mill, Terry’s was built like a red-brick university, the dominating clock tower the main concession to the disciplines of factory life. The river flowed on one side, to the Archbishops’ Palace; the green acres of Knavesmire race-course stretched out on the other; but around the northern city approaches were the streets of workers’ houses, which remain mostly untouched by the slum clearance or gentrification of the inner city.

Finsbury Street was one of them, populated by working-class families of long standing, or by young, ambitious and upwardly mobile workers like my parents, Len and Edith Cable, stepping on to the first rung of the housing ladder. My memories are sparse: the smell of drying clothes; the excitements of the street such as the horse and cart bringing sacks of coal, and the rag and bone man; the cruel cold of the outside lavatory. Some memories are more ambiguous, like the large metal bathtub in front of the coal fire, which may well have been for me, but possibly for the family, as it was when I needed later on to impress left-wing audiences with my proletarian origins.

It was the walks along the River Ouse which remain clearly etched in my mind. Stopping off at Rowntree Park, donated to the city by the bigger chocolate manufacturer, where a magical store dispensed an endless supply of ice creams and there was a large lake which sucked my toy boats into a miniature Sargasso Sea where they remained, becalmed, for ever. Past the Rowntree’s baths, whose freezing waters deterred me from swimming until well into adulthood. Under the pulleys and winches and cranes that lifted jute sacks of grain and exotic-smelling fruit from barges into the warehouses, now luxury flats. To Lendal Bridge, looking across to the Tower where York’s Jews had once been herded into a medieval holocaust, whose flames lit up many a childhood nightmare. Then, inland, past the Bar walls, dodging the arrows which rained down from the battlements. To the streets off Bishopthorpe Road: on one side rows of terraced houses with gaps of rubble left by German bombs; on the other, intact, Vine Street, where my mother’s family, the Pinkneys, lived.

Their house was dominated by the spirit of my dead grandfather, a sportsman of distinction, who had once been a star of the breakaway professional Rugby League and a railway clerk. His life had been dominated by the First World War: captured in 1917 after battles in France, interned in a German prisoner-of-war camp, and returned home disabled by gas and ill-treatment in prison. He never worked again, but remained a brooding presence perpetuating hatred of the Germans, firm family discipline, and working-class respectability. My grandmother, Annie, boosted the family income as a charlady, but it was not enough and when my mother reached fourteen she was sent out to work, despite the protests of her teachers who had recognized her ability and creativity. The Pinkneys stayed clear of the pit of depravity inhabited by their rougher neighbours by means of hard work, temperance and voting Conservative. Grandmother made time after her early morning office-cleaning to distribute leaflets for the patriotic, Tory, Primrose League. My mother recalled that when she dated a young Irish socialist from down the street – one Bill Burke, later Labour leader of York City Council – she was beaten with a leather strap.

The Pinkneys were a warm, close family, populated by friendly aunts from the surrounding streets, who stuffed my mouth with chocolate from blue-paper packets: factory ‘waste’ from Terry’s, which was a luxury not rationed by the little books which then defined our food intake. Much of the warmth came from my mother’s sister Irene and her husband, Reg Mothersdill, a plasterer, whom I remember for his shining, brilliantined hair, endless chain of Woodbines, and tales of his war exploits escaping from sinking ships.

Unlike the Pinkneys, the Cables – my father, his brother and his father – had no direct experience of war. My father had been an ‘essential worker’, making and repairing aircraft in the village of Sherburn in Elmet, near York. His battles were against the stifling hierarchy of British class and educational privilege which had undervalued him from an early age.

His widowed mother – another Annie – lived in Layerthorpe, close to a notorious slum in which the family owned a grocer’s shop. Their house was separated by a railway line from the mean streets that Joseph Rowntree had surveyed a century before, and, as its name implied, Glen Avenue was respectable enough – but not far enough away to escape the foul smell of the gasworks, which penetrated every nook and cranny.

Grandma’s shop and, when he was alive, Grandfather Cable’s income as a draper’s assistant were enough to lift one foot out of the working class, but not both. My father’s elder brother Reg was sent to a grammar school, then fee-paying, to prepare for a professional career, but there was not enough for my father, who was sent out to work as soon as possible. He recalled being sent around the streets shovelling manure from behind passing horses to earn a few pennies. But through aptitude and application he progressed to skilled work in the joiner’s shop in Rowntree’s factory, where his brother, after school, began a managerial career.

The resentments created by this sibling discrimination continued for many years, and family history as it was passed down to me was undoubtedly coloured by it. My mother – who sided with my father in this family feud, if not in much else – insisted that Grandma Cable was illiterate, though her copperplate handwriting suggests otherwise.

It was inevitable that, for a man of my father’s intelligence, frustrated ambition and energy, the factory jobs and small terraced house were mere staging posts. And so it proved. One day, when I was just over four years old, a van came to carry away our furniture and I was carried, my feet dangling over the tailboard, to a new home.

*

The next step on our long social climb was Grantham Drive and a small, semi-detached house with a garden. My father, planning his next career move, was away at teacher-training college, which equipped him to impart his technical skills and not just practise them. My mother, at one bound, was promoted to the status of a middle-class housewife. And I started my own ascent of the educational Alps at the base camp of Poppleton Road Primary School.

In appearance and in reality, Poppleton Road Primary – still virtually unchanged in its century of existence – was an education factory, producing batches of children neatly sorted for the next, selective, stage of their manufacture. It towers on a hill above the low-lying river basin of the Ouse, rivalling the Minster in elevation, if not in architectural distinction.

I remember little of the early years beyond the smell of heaving, damp children on rainy days and the sordid mess of the toilets which dictated the rhythm and programme of my day, desperately holding on until I could get home without the humiliation of being caught short. There were memorable treats, like the boxes of red apples from kindly Canadians, sent to ease our post-war deprivation (I am not sure if the Canadians knew about our hoards of chocolates).

I struggled most of all with writing and never mastered the art of dipping the metal pen into the ink-pot and reproducing the required italicized print. I owned a pet spider who followed my pen round the page, leaving frequent blobs of black or blue. Until rescued many years later by the great Hungarian inventor László Bíró, I distressed teachers and parents alike by my lack of nib control.

But I clearly did something right. One hot summer day, the seven-year-olds were assembled in the playground and a roll call divided us into four lines. We knew that something momentous was afoot. As the clever goats gradually separated from the duller sheep, and even lesser species, we began to understand the choice was not random. I was relieved to be in the line assigned to Miss Whitfield, who always taught the top stream. Whether through astute judgement or self-justifying prophecy, the same group remained pretty much together in our respective schools for the next ten years or so. Our friendships with the other children became gradually attenuated.

Schooling acquired a new sense of purpose and direction: gaining more and more stars to add to the line snaking across the wall against my name, and achieving higher and higher ranking in the endless competition in ‘mental’ and ‘mechanical’ maths, composition and spelling, and the gamut of academic subjects that entered the curriculum. Praise at home followed praise at school, and I had plenty of encouragement to become a school swot.

Most swots had a hard time from their less academic contemporaries. Segregation by class did not provide protection in the playground or on the way home. I somehow survived that. I was tall and, also, in one fortuitous episode, acquired a fearsome and wholly unjustified reputation as a playground warrior. A small boy called Higginbottom demanded a fight at playtime and dozens of boys gathered round, chanting ‘Blood! Blood!’ His fists flailed wildly but they did not reach me on account of my having longer arms. Out of frustration he charged and I ducked from his blows. The duck, somehow, became a well-directed headbutt and soon the ground was fertilized with blood from his broken nose. I found myself carried around the playground in triumph and was never attacked again.

I was also rescued by reasonable competence in sport, achieved through endless games of street football and cricket, both played with tennis balls. I learned the importance of earning grudging, classless respect by heading a heavy ball or winning a tackle in the middle of the bog that passed for the school field, or being familiar with the weekly exploits of York City, thanks to my father who was a fan, and York’s Rugby League team, with which I had an ancestral connection.

Along with books and ball games, like most children, I endured my share of terror and boredom. Both of these centred on God. My parents were God-fearing folk who attended the Baptist church for services twice a day with, for me, the added spiritual bonus of Sunday School. I heard it said that my father had studied to be a pastor and had attended a Bible college in Northern Ireland to this end, but there is no corroboration for this family story. Church was, nonetheless, a central pillar of their existence. Like most small boys, I understood little of what was going on and endlessly fidgeted with boredom, but was a dutiful little Christian, earning many heavenly credits by identifying obscure quotations from the lesser prophets.

One day, however, a serious religious schism occurred. We were late for a bus and I released a torrent of profane abuse learned in the school playground, but not understood. My father warned me that I would be punished and I was severely beaten when we returned home that evening. I felt a bitter sense of grievance and, for long afterwards, blamed God for the injustice of it. I also experienced nightmares centring on the figure of God in the religious painting hanging over my parents’ bed, and screamed until it was removed. My apostasy must have been infectious, for the family stopped attending the Baptist church soon afterwards because of a bitter row the spiritual or personal origins of which were never explained to me.

The weekly cycle of boredom reached its climax with the ritual Sunday visit to Grandma Cable, for which I was required to be well scrubbed, seen, but not heard, and exceptionally well behaved. I suffered badly by comparison with my angelic cousin John, the adopted son of Uncle Reg and his wife Evie. I knew, however, that cousin John was not real, because I had helped to choose him from a book of orphans. The Cables had agreed that ‘coloured and half-caste’ children were unacceptable, and some of the other waifs and strays looked, even as toddlers, as if they were destined for a life of crime. In the middle of this unsavoury band of infants there was, however, a cherub with blue eyes and blond curly hair, lacking only wings. He duly became cousin John, the exemplar against which I was to be measured: his cleanliness advertised by a permanent smell of carbolic soap; his godliness undimmed, like mine, by doubt; and his heavenly voice untouched by late adolescence, remaining firmly stuck in the castrato range. He seemed, even as an infant, altogether too good to be true. He was. But the full scale of the ensuing disaster only became apparent after a couple of decades, when his hereditary Huntington’s disease manifested itself.

My appetite for terror and my flight from boredom were both met in the fantasy world of films, radio and books which filled my childhood. Television did not arrive until my mid-teens. It was the vivid images from the weekly visit to the cinema that lingered in the imagination. My dreams and daydreams were long haunted by the early scenes from David Lean’s Great Expectations, which my parents unwisely judged to be the best occasion for my cinematic baptism, aged six. The misty marshes of the Thames Estuary seemed uncannily like the familiar river-scape of the Ouse, and I could all too easily envisage a Magwitch-like convict emerging from the fog to snatch me. I progressed to the comfort zone of Westerns, where the good guys in the cavalry always managed to wipe out the Indians, and war films, where heroic Englishmen could be relied on to blast the Hun out of the skies or the seas. Some films had a profound influence: Where No Vultures Fly, which graphically captured the cruelty of ivory poachers in Kenya; Humphrey Bogart fighting off leeches in TheAfrican Queen, before a kamikaze attack on a German gunboat on Lake Victoria; and later, Simba, a horrifying depiction of Mau Mau oath-taking rituals and murders, also in Kenya. I had decided at an early age that, unlike my contemporaries, who were preparing to be train drivers, motor-racing drivers or spacemen, I would become a Big White Chief in Africa, ruling over the natives.

By the time I was eight, my father was on the move again to a bigger and better semi in New Lane, overlooking Holgate Park, near the rapidly expanding suburb of Acomb, our upward mobility underlined by the fact that our new neighbour was a bank manager. Our move was at least partly precipitated by our noisy neighbours, the Smithsons, who, these days, would probably have been in line for an ASBO. My father’s main retaliatory weapon was to place our radio against their wall at full volume, covering it with blankets to dull the sound on our side. He failed. We moved.

For me the new home in New Lane sat in the middle of a vast adventure playground. Opposite were the woods of a park opening up to playgrounds and playing fields. The road itself led into a country lane lined with hedgerows, which led in turn to the wilds of Hob Moor. In the other direction was a disused windmill surrounded on three sides by a wilderness of scrub and trees, which were a perfect setting for Custer’s last stand and for ambushing the Sheriff of Nottingham. Though I understood nothing of economics at the time, the country lane and the wilderness were becoming prime sites in the post-war scramble for development land, and they gradually disappeared during my childhood. But these were the happiest years of my early life: friends (all boys), boundless space, and a freedom to roam that would be inconceivable today. It is tempting to romanticize the days before family cars, televisions and expensive toys, but even in the more protective and disciplinarian homes like mine there was a degree of trust – in neighbours, in strangers, in the safety of roads, and in the common sense of children and their instinct for self-preservation – which has largely gone. We somehow survived without protective helmets and without encountering predatory paedophiles or murderous gangs. Occasionally there was a really serious treat: a day in Leeds on the trams and trolleybuses; or a week in Scarborough or Filey, by train to a dreary boarding house and the hope that the weather would permit the use of buckets and spades. But it was treat enough to own the streets and the wide-open spaces.

A couple of years later, when I was ten, a series of events occurred in quick succession that radically reshaped our lives. My mother bore another child, Keith, and, like many unplanned, younger children, he was adored by his parents and elder brother. She succumbed, however, to what is now called post-natal depression but was then seen simply as a form of madness. She was taken to York’s mental hospital – what my friends called the ‘the loony bin’ – and my brother was fostered for the best part of a year. The breakdown was not difficult to explain: her mother had just died; her sister, whom she loved dearly, had emigrated to Australia with my other Uncle Reg and my cousin Susan; her factory friends were no longer suitable company. Marriage had produced suffocating tedium and isolation, cooking and cleaning, serving three meals a day to a bad-tempered husband working off the slights and frustrations of the staff room in the technical college where he was now teaching, a clever but ungrateful son – and now a baby. Something also snapped in the relationship between my parents and I saw, or was aware of, violence for the first time (my brother, who witnessed episodes later in his childhood, recently reminded me of this, something I had managed to erase from my memory). When my mother returned from hospital she gradually put her mind together again with the help of adult education classes, but for the rest of my childhood and adolescence she was a damaged and diminished figure, usually found talking to herself in the kitchen.

Shortly after my mother’s breakdown there was the eleven-plus. I had done well at school, but nothing was guaranteed. I was, moreover, becoming a vehicle for my father’s frustrated ambitions. He might well be a mere craftsman amid the graduates in the technical college staff room, but his son was smarter than theirs. He was no fool, and understood long before Britain’s educational establishment that intelligence was acquired, not innate. So I was set to work on practice IQ tests, as well as English and maths, progressing from initial bafflement to marvellous fluency. I passed easily enough, along with most of the top stream at Poppleton Road. But there were some casualties, like the pretty girl on the next desk, who collapsed sobbing when the results were announced in class and disappeared through the trapdoor of education into a secondary modern school. I never saw her again. That episode more than any other persuaded me that, although I was a beneficiary of it, there was something fundamentally wrong with the eleven-plus system of selection.

My father discovered, from his contacts in the education department, that not only had I passed but that I had gained the highest marks in the city. This entitled me not merely to a grammar school place but to compete for a single place at the cerebral Quaker public school, Bootham, or for one of five places at the posh and ancient St Peter’s. I went for Bootham, my father having been advised that admission was a formality. Only an interview stood in the way – on my interests and my reading – with the distinguished head, Mr Green. I was extremely well prepared, with a compendious knowledge of the world’s capital cities, Test match results, and the full sequence of English kings and queens. I was a well-travelled young man, having explored northern England with my friends, looking for rare train numbers in engine sheds, as far as Gorton in Manchester and Blaydon in Newcastle. I had read voraciously: the complete Biggles series of Captain W. E. Johns and two comics a week, which kept me fully up to speed with Dan Dare’s battles with the Mekon and the fish-and-chip-eating running-track genius, Alf Tupper. It soon became clear, however, that Mr Green was neither excited nor impressed by this knowledge. He asked me to read a passage from Milton’s Paradise Lost. I floundered, desperately trying to read, let alone interpret, this ancient gibberish. A few days later I received a letter confirming that I would not be going to Bootham but to Nunthorpe Grammar School. My father had, however, learned from this disaster and when he later repeated the eleven-plus success with my brother Keith, he was better prepared. Keith went to St Peter’s, but detested the snobbery, underperformed, and always envied me my failure. Meantime, I flourished as a big fish in the smaller pool of a grammar school, along with my friends from Poppleton Road.

Chapter 2

You’ve Never Had It So Good

The 1950s saw my family firmly established in the lower reaches of the English middle class. And post-war prosperity brought a stream of new objects into the home: a vacuum cleaner, a washing machine, and eventually – and most reluctantly – a black-and-white TV, then a (shared) telephone and a Morris Minor. These purchases were all approached with great circumspection and we lagged behind the Joneses. My friends, whose fathers worked in the railway carriage works, and our poorer relatives were not sure whether to put this down to the Cables’ snobbery or meanness, especially when I was reduced to knocking on their doors, asking plaintively to see Billy Bunter or The Lone Ranger. In truth, my parents were puritanical, never drank or gambled – my father’s pipe being his only vice – and they resisted new-fangled acquisitions until abstinence put them at risk of ridicule.

In general, I added lustre to the family’s achievements and upward mobility. Every prize-giving at Nunthorpe yielded another addition to our collection of encyclopedias and dictionaries. Occasionally, however, I brought shame. I discovered an air rifle and ammunition hidden in a bedroom cupboard. With my friend Duncan, our games of white game hunter were transformed once we discovered that we had the weaponry to hunt and terrorize the cats and dogs of New Lane. We progressed to being Second World War heroes directing sniper fire at Nazis hidden in the bedrooms of our neighbours. After local chatter disclosed a rash of broken windows and airgun pellets, someone traced the angle of fire back to my bedroom and, before long, a policeman appeared at the door. We were duly hauled off to York police station, but contrition, a blameless record, and my father’s references to his influential connections in the city, got us off with a caution. This brush with the law was especially shocking to my parents, and also to me, since I had never previously shown much inclination towards criminality beyond such peccadilloes as pelting elderly people with snowballs. I was part of an orderly society in which we deferred even to such minor authority figures as park keepers and bus conductors, let alone the police.

With my mother relegated to baby-minding and household chores, my father superintended my teenage upbringing, and with rather closer attention after the episode with the gun. In many ways he was an exemplary father who kept me motivated at school but gave me space to play. He took me to London and regularly to football matches, including the 1955 cup semi-final when York almost achieved the impossible feat of beating Jackie Milburn’s Newcastle at Hillsborough, having earlier disposed of Stanley Matthews’s Blackpool.

He was a dominating personality, with great drive. He was also a bully who crushed weaker spirits, like my mother, but energized others, including many of his pupils. He was known at the college as Hitler, on account of his moustache and his reported ability to invest the teaching of even the most recondite corners of building science with the fervour of a mass rally. He married the skills of teaching and communication with those of a fine craftsman. His technical drawings were almost works of art, blending precision with elegant form and colour. Later, in retirement, he sketched with remarkable accuracy, and in detail, all of Britain’s cathedrals. In the staff room, however, where he inhabited a twilight world somewhere between the graduate lecturers and the technicians, his confidence evaporated and he suffered years of indignity and real or imagined snubs.

He saw part of his parental duties as introducing me to political ideas and the art of debate. There was, however, little scope for reasoned debate, since his views had all the flexibility of the reinforced concrete he tested to destruction at work. He was unswervingly Conservative, his philosophy built on unquestioning loyalty to the monarchy, the army and the police, the sanctity of property, rewards for thrift and hard work, hanging and flogging for criminals, Britain’s imperial glory, the innate superiority of white people, and the ingrained subversiveness of socialism and trade unionism. The last was particularly difficult to understand since at Rowntree’s, and at his wartime aircraft factory, he had been a union shop steward and was apparently trusted by his workmates. Later in life he became President of his union, the National Association of Schoolmasters (NAS), compromising his hostility to collectivism because of the cause it served: fighting equal pay for women. Women were, he believed, steadily destroying the teaching profession, dragging down pay and undermining discipline at the chalk-face. Married women did not need full pay because they had husbands, and single women did not have a family to support. The NAS, a powerful union led by one Terry Casey, grew up around those doing battle with the feminist-and communist-dominated National Union of Teachers. The NAS eventually merged with a rival women’s union to become the NAS/UWT, and I suspect that it has buried the politically incorrect misogyny that inspired it and so attracted my father.

Trade unionism was but one of the perverse subtleties of his Toryism. He was also fiercely class-conscious and detested ‘toffs’ like York’s MP, Sir Harry Hylton-Foster, who had once brushed aside a problem my father had brought to the constituency surgery, patronized him and addressed him as ‘my good man’. Like the middle-class man in the John Cleese–Ronnie Barker–Ronnie Corbett sketch, my father looked down on the working class but also resented being looked down upon by his social superiors.

Eventually Nirvana arrived, courtesy of a grocer’s daughter, Mrs Thatcher, and though he only lived to see three years of her earthly paradise he lived every minute like a Bolshevik revolutionary who has glimpsed the promised land. Even after a heart attack, aged seventy, he rushed out into the snow to deliver more Conservative leaflets, contracting the pneumonia that killed him. He died fulfilled and, though I did not altogether share his passion for Mrs Thatcher, I saw, then, what I loved in him.

My political education consisted of listening to rants directed against his many bêtes noires. Chief among these were the colonial upstarts who expressed their ingratitude to their mother country by demanding independence. India had been abandoned without a fight by the socialists, and now even the Conservatives were having to negotiate with uppity natives like Nkrumah and Makarios, while evil communists like Jomo Kenyatta lurked in the background. But it was the Arab upstart, Colonel Nasser, who brought him to paroxysms of rage. When the Suez crisis arrived he registered his anger at hearing Nasser’s voice on the BBC by hurling shoes at the radio. He would calm down the following morning when our newspapers, the Daily Mail and Sunday Express, provided what he regarded as a more balanced assessment than the unpatriotic BBC. Suez confirmed all my father’s worst suspicions: Britain had been stabbed in the back by socialists and pacifists at home and the United Nations and the Americans overseas. Only the plucky Israelis emerged with any credit. For someone with anti-Semitic prejudices, my father had a strange infatuation with Israel and it was the only country he ever expressed any interest in visiting: the product, I think, of his Old Testament religion combined with relief that someone was giving the Arabs the thrashing they deserved.

Suez and the Hungarian uprising, both of which occurred around my thirteenth birthday, triggered in me a first stirring of interest in politics. I devoured the newspapers and numerous books on current affairs and began to see through the fallacies and factual inaccuracies of some of my father’s arguments. I ventured to contradict him, which usually angered him further but occasionally prompted a bemused respect. I could even begin to see the limitations of my father’s favourite tracts – like the dyspeptic column in the Sunday Express written by John Gordon, aka John Junor (the Richard Littlejohn of his day), exposing humbug and hypocrisy on the left – which, since he no longer went to church, had come to fill the gap left by the Sunday sermon.

Like most adolescents, I was emotionally and intellectually confused, very dependent on my parents, but increasingly rebellious, especially towards my father. I had two role models, both close friends, who in their different ways represented the zeitgeist of 1950s youth and sought to attract me into their respective orbits.

One, Duncan, was my fellow delinquent in the airgun incident. He was a rebel without a cause. He was the only son of a quite elderly couple who had befriended me, taking me on their family holidays, which left me with an abiding love of Britain’s fells and moors but bored Duncan to tears. He experimented, at an early age, with the joys of cigarettes (then the recreational drug of choice), sex, motorbikes, and the garb and companionship of Teddy boys. He left school at the first opportunity, without O levels, to earn money to finance his motorbike, which almost killed him in a horrific accident, and progressed rapidly to early marriage and parenthood, then early divorce. We gradually drifted apart, having only a passion for Elvis in common.

A bigger influence was rebel with a cause, David. David’s father was a left-wing shop steward at the nearby carriage works, where many of our neighbours were employed. Specifically he was a Tribunite: the Tories were the Devil; Bevan was God; Gaitskell was Judas; and Michael Foot was the chief apostle of this sect. His son expounded this brand of true socialism with the same didactic, uncompromising certainty as my father showed in the opposite political direction. We had a third friend, John, whose father had a white-collar job and read the Daily Telegraph. Aged fourteen or fifteen, we wandered the streets of York in the evening, stopping for bags of scraps (bits of cooked batter) with salt and vinegar at the fish shop, while my two friends aimed ideological broadsides at each other and I tried to arbitrate a ceasefire. I already understood John’s Conservatism, from home, but David introduced new concepts, like nationalization of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the class struggle, which seemed to me of little relevance in a quiet, increasingly prosperous place like York, but which were announced with such conviction that it seemed churlish, as well as unwise, to contradict him.

David introduced me to more than socialism. He was a genius with cars: by the time he was sixteen he had built his own fibreglass sports car, and took me to see future Formula One heroes like Jim Clark and Mike Hawthorn racing on the aerodromes around York. He was a fine artist, passionate about Impressionist and post-Impressionist art and, since I was his favourite captive audience, educated me in the works of Picasso, Klee, Modigliani and Dalí. Most remarkably, he was a womanizer of discernment and considerable experience. Despite his unprepossessing appearance – spotty face, horn-rimmed spectacles, hunched back and scruffy duffel coat – he pulled girls of, to me, remarkable beauty. When my friends and I doubted his sexual escapades, he would produce nude portraits of his latest girlfriend. He tried to introduce me to members of his harem, but while I could cope with socialism and Fauvism, women were altogether more alarming. David had what is now called charisma, and plenty of it.

Our friendship was put to its greatest test after he announced, shortly before the 1959 general election, that he was leaving Labour and joining the Communist Party. He was fed up with effete public schoolboys like Gaitskell undermining the Labour movement with social democratic treachery. There were revolutionary stirrings in the York working class, he announced, and it was time to fight the spread of false consciousness among the masses. When the general election was announced, the headmaster of Nunthorpe told us that the school would have its own. The aim, I think, was to let the upper-sixth practise their debating skills, but David put himself forward as the Communist candidate, citing me as one of his seconds. He produced dazzling posters, painted by himself, and agitated vigorously among Nunthorpe’s lumpen proletariat in the lower forms. Nationalization and class war did not have much resonance as issues with grammar-school boys in a city with no history of industrial strife. But the burgeoning Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament did, and David skilfully promoted it.

The authorities panicked and it was announced that the Communist candidate had been disqualified for unspecified irregularities. I was secretly relieved, but David was outraged at this assault on democracy and civil liberties. He called for a school strike and civil disobedience. No one joined him on the picket line, where he shouted ‘Scab’ at the strike-breakers. I arrived head-down in the middle of a peloton of cyclists to avoid his gaze. His friends, including me, slipped away, and he reappeared a week later with a sick note. I voted for the Liberal. My friendship with David was never quite the same again. After A levels he went to art school, from which he claimed he was expelled for setting fire to the buildings during an ‘industrial dispute’.

The 1959 election also proved a turning point for my mother. One day she broke down in tears and confessed to me – once I had pledged secrecy – that she had done something terrible. I thought initially that she had killed someone, but it transpired that she had defied my father’s instruction to vote Conservative. In the privacy of the ballot box, she had supported that nice Mr Jo Grimond. From then on we formed a secret Liberal cell in the Cable household and she remained a supporter until she died.

Another liberal (and Liberal) influence was the Quakers. After the Baptists, I had wandered from one religious denomination to another, not so much in pursuit of spiritual nourishment as friendship. I spent several years with the Methodist chapel at the end of the lane where services were made tolerable by lusty singing of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’, ‘Stand Up, Stand Up for Jesus’ and ‘There is a Green Hill Far Away’. The chapel organized Cubs, provided film shows after Sunday service, and asked little of us beyond signing a temperance pledge, breaches of which I have always associated with the fires of Hell and, perhaps for that reason, have broken only moderately and occasionally. One of my friends, however, lured me away to the Society of Friends when I was about eleven. I never warmed to the stillness of the Meeting as I did to Methodist hymns, and I never embraced pacifism, but I greatly liked the people, who were kindly, generous and compassionate, and made me welcome without testing my convictions. And while my father feared that I was being indoctrinated by liberal and left-wing ideas, he saw merit in my being involved with York’s social and intellectual elite, including the Rowntree family, and I stayed with the Friends until I left for university.

My only problem with the Quakers was that I never saw God through the goodness and I worried seriously that, despite being a regular church attendee since my childhood (a somewhat more regular attendee than my God-fearing parents), I had never encountered anything that could be remotely described as a religious experience. Nor have I since. I decided at one point to visit each of the churches in York that I had not previously attended, looking for God, and went to the Mormons, Christadelphians, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Presbyterians, Unitarians, and various shades of Anglicans. My market research suggested that the Methodists had the best hymns, the Anglicans the best churches, and the Quakers the nicest people and prettiest girls (from the Mount School). But the Almighty eluded me. I was left with a sense of the importance of the spiritual dimension of life, and I still have a yearning for Him and for whatever it is in Christianity that provides me with such comfort and inspiration. But I struggled then, and always have, to get to grips with faith, as if I was trying to grab a particularly elusive bar of soap.

Politics was easier to understand and, warming to Liberalism, I market-tested this new political allegiance on my friends. The overwhelming consensus was that Liberals were a wasted vote. Conservatives complained that ‘they let Labour in’ and socialists that ‘they let the Tories in’. Even my ill-formed political mind could grasp that while one or other proposition might be true, they could not both be true at the same time. Nineteenth-century history, taught in the O level curriculum, also led to the conclusion that Liberals were progressive and a Good Thing, while Conservatives – Disraeli excepted – were reactionary and a Bad Thing. That was broadly where I remained until midway through university.

Nineteen fifty-nine was a crucial year in other respects. It was time to choose A level subjects. I had begun to develop a certain flair in history essays thanks to an inspirational figure, ‘Jimmy’ Jewell. I was also discovering the delights of Thomas Hardy and Shakespeare and the war poets; and actually enjoyed translating Caesar’s Gallic Wars. However, my father had a deep suspicion of ‘ arty-farty’ subjects, a suspicion deepened by the fact that my mother, thanks to the adult college, now went around the house speculating about the nature of being, rather than attending to her domestic duties. In his sternly utilitarian view, there were serious choices to be made: did I intend to become an accountant, a lawyer, a teacher or a scientist? The last seemed the least of several evils and I embarked upon maths, physics and chemistry, in which I had shown competence but no great flair or passion.

As luck would have it, the choice proved less clear-cut than I had feared. Mr Jewell auditioned every two years for his Shakespeare production with the neighbouring girls’ grammar school, Mill Mount, where his wife, Joyce, was the drama teacher. The play was his pride and joy, taken immensely seriously, with theatre critics summoned from as far as Hull. That year’s play was Macbeth. I had no expectations beyond being a stagehand or spear-carrier, being shy, inarticulate and wholly untested. Moreover, I had offended Mr Jewell deeply by reproducing in a history essay some anti-Semitic diatribe I had picked up from my father, not appreciating that Mr Jewell was Jewish. He forgave that indiscretion, understanding, I think, where the nonsense had come from. He also found in my reading of the lines at the audition some dramatic quality that had escaped me and everyone else, and gave me the leading role.

A few months later I had mastered several hundred lines of blank verse, learned the rudiments of acting, and overcome my terror of speaking in public. Olivier, however, I was not, and on a disastrous first night I came on a scene early in Act Five to confront a group of baffled little boys advancing across the stage carrying branches: Birnam Wood in motion. The little boys took fright at a sixth-former with a false beard waving a sword at them and fled to the wings, and Shakespeare’s tragedy dissolved into comic melodrama. By then, however, the dramatic tension had long since gone, not least because of the catcalls from the boys in the audience who had noticed that the backlighting revealed the three Mill Mount witches to be naked underneath their diaphanous gowns. Still, things got better after that, and I was credited with capturing some of the poetic quality of Shakespeare.

*

The play also introduced me to Lady Macbeth, who became my first love. Until that point I had been terrified of girls, and uncomfortable with women in general. My mother had become almost invisible after her breakdown, and the moments of tenderness I remembered from years before had been long since lost in the daily routine of a home dominated by the appetites of men and boys. My surviving grandmother, Grandma Cable, and I enjoyed a strong, mutual loathing. She had, in any event, been banished to an old folks’ home where she claimed she was being detained against her will, constantly insisting that she was being robbed of all her money, and sitting with her stockings and knickers round her ankles, smelling of urine.

By our mid-teens, the barriers created by gender segregation at school had begun to break down. Relationships were measured on a primitive metric: Grade 1 was holding hands; Grade 2 was full-on kissing; at Grade 3 hands got inside bras; Grade 4 was heavy petting; and Grade 5 was intercourse and beyond. Conversation, let alone love, didn’t enter into it. A few of my precocious friends had reached Grade 5 early on, or claimed to have, competing to be the school’s Casanova and generating innumerable pregnancy scares around the city. Most of us, however, were clustered at the bottom of this ladder of sexual achievements and hadn’t made Grade 1. I was generally thought to be pretty eligible, but underdeveloped, and received plenty of encouragement, including being paired off with a dark, flirtatious beauty called Carol. After two circuits of Hob Moor, where courtships occurred, I had not dared to utter a word or approached within a foot of her and she suggested I try someone else.

Audrey was a Grade 2 girl, the maximum allowed by her Methodism, and she was my first real girlfriend. Apart from a mutual interest in physics and chemistry, however, conversation was sparse. We both resorted to bringing to our dates a checklist of talking points suggested by friends, but they were exhausted after a few minutes and the hours hung heavily. Another, more suitable and articulate, boy was found for her.

Lady Macbeth, Marion, had enormous eyes and a dazzling, wide smile but no chest, which made Shakespeare’s allusions to her breast-feeding a source of considerable ribaldry among the more disrespectful juniors. Indeed, she suffered seriously from what is now called anorexia, though it was concealed beneath well-chosen, flowing garments. Our first date hit the buffers when she announced that she did not like to be touched by boys. Nonetheless, the relationship flourished and we became inseparable, talking endlessly on the streets or by phone about everything under the sun, including sex, albeit theoretically. We worked our way through the modern novel, concentrating on Lawrence. Marion saw herself as Miriam from Sons and Lovers, doomed to frigidity by a mysteriously unhappy upbringing, and urged me to find an Ursula before it was too late. Lady Chatterley’s Lover had recently escaped censorship and we endlessly deconstructed it. Unfortunately, I carelessly left the copy at home, where it was found by my father who insisted that he, and my mother, should read it ‘to find out what the fuss was all about’. To my amazement their reaction was restrained and good-humoured. While deploring the sexually explicit passages, which they obviously understood better than I, my father even ventured some perceptive comments on Lawrence’s florid style and the thinness of the plot. This episode caused me to reassess my father, whom I had come to see in a monochromatic light as a bullying neo-Nazi. He had, in fact, a generous and tolerant side, as I should have more readily appreciated since, when I was old enough to drive, he allowed me to use his new car for my trysts with Marion.

Although we were very close, the relationship became a source of concern, as well as ridicule, among our friends. We became Darby and Joan. Marion was offered counselling by her earthier classmates. She decided on drastic action and after a holiday abroad announced that she had lost her virginity to a German. She reassured me that it had been an appalling experience which I had been spared. Shortly afterwards, she invited me to her bedroom and undressed. Whether it was my shyness or my shock at her emaciated body I am not sure, but nothing happened and we retreated into talk. Another attempt, equally ignominious, failed several months later, and we settled for platonic love. Marion arranged for me to go out with her friend, Gwyneth, an altogether less emotionally complicated, more physical and affectionate girl – so much so that I panicked and, unforgivably, fled while she was sitting her A levels.

When Marion and I met as students some years later, she explained that her problem had been that she was really a lesbian but had only just felt able to ‘come out’. This seemed a plausible explanation, but its full accuracy was put into doubt when I met her mother while canvassing in the 1983 general election, who explained that Marion had emigrated to the USA, met a man half her age, and was now happily married with four children.

Somehow, amid this emotional turmoil and artistic distraction, I coped well with advanced calculus and the periodic table and was one of a small number of boys deemed by the head to be Oxbridge material. As such, I qualified for a grossly disproportionate amount of senior teachers’ time. The head, Henry Moore, was anxious to push Nunthorpe from its status as a middling grammar school into the big league occupied by the direct grant and public schools which counted their Oxbridge entrants in double figures. A place at Oxbridge, or a highly prestigious red-brick institution like Imperial College, merited a half-day celebratory holiday for the school, so I did not lack encouragement.

Added motivation came from being appointed Head Boy ahead of an altogether more focused and disciplined rival. My appointment caused nervousness among the staff because my standards of dress and punctuality fell well below acceptable norms and the Head Boy had considerable devolved authority for imposing the school rules. Reflecting, no doubt, the changing mood of the times, standards of discipline were confusingly inconsistent. Some younger teachers opposed corporal punishment, but a few of the old lags relied heavily on canes and rubber tubing, sometimes administered with medieval sadism, for petty offences. I added to the moral confusion by zealously enforcing the rules that I agreed with and ignoring others. Noise levels rose alarmingly in break times, playground fights proliferated and the paper dart industry flourished, but smokers were not tolerated. There was not, then, a scientific basis for the smoking ban, but with a zealous gang of enforcers I tracked down every illicit smoker behind the toilets and bicycle sheds and in the surrounding streets and hauled them off to be given six of the best by the deputy head. This apart, I saw my rule as one of enlightened liberalism until, quite recently, I met an old boy with an altogether different perspective, who could, aged sixty, still recite the innumerable lines I had given him for some trifling misdemeanour.

Getting from Oxbridge potential to an Oxbridge place was not, however, straightforward. The market for theatrical scientists with an interest in current affairs proved difficult to penetrate. I was turned down by innumerable Oxbridge colleges and other universities and ended up with offers of places at King’s College, London, to read chemistry and Nottingham to study social administration. Someone then suggested Fitzwilliam House, Cambridge, now a serious academic college, but at that time known, like St Peter’s at Oxford, as a college of last resort, mainly for rugger-buggers and other sporting hearties. True to stereotype, the senior tutor complimented me briefly on the quality of my physics entrance paper and then showed more interest than anyone before – or since – in my performance as first-team opening bat and wicketkeeper, occasional left-back for the soccer team, very occasional rugby player – both codes – and county trialist in school hockey. He wrote ‘Blue?’ on his notepad and I was admitted to read natural sciences.

The headmaster and Mr Jewell were delighted, though their investment in Oxbridge entrants proved unproductive because the school soon became an 11–16 mixed comprehensive and is now better known for its non-academic alumni like Steve McLaren, the former England football manager.

My father was over the moon. His investment had certainly paid off. I felt rather sorry for his colleagues at the technical college who now faced massive retaliation for two decades of humiliation by being endlessly reminded of his vicarious achievement: a son at university – and Cambridge, no less. Indeed, the family cup ran over: Dad achieved a long overdue promotion; we moved a big step up the ladder of social stratification by moving to a detached house in a quiet and respectable cul de sac in Dringhouses, near the racecourse; my brother Keith won an academic scholarship to a public school, St Peter’s. The Conservatives then won a general election on the slogan ‘You’ve Never Had It So Good’. It certainly appeared so for the Cable family.

For my mother, however, my success brought mixed blessings. Her pride was deep and genuine, but it meant exposure to new, clever people, who might mock her accent or disparage her lack of formal education. Upward social mobility and success energized my father, but my mother shrivelled. She had overcome her inhibitions to the extent of becoming a tourist guide at York Minster. But she nonetheless carried around the fear that some educational or social indiscretion would betray her humble origins, and she would dwell for weeks on the shame of a misplaced vowel in conversation with someone important. She was happiest away from people, producing art of high quality. The new detached house, moreover, presented a whole set of problems in itself, like neighbours who cared rather more for appearances than the socially mixed crowd down New Lane. In particular, a poisonous Conservative branch chair, Stella, who dripped venom with every phrase, acted as the custodian of local standards and mores. My father’s growing expansiveness and my mother’s introversion caused growing tension. Home was not a happy place, and I was relieved to escape.

The relief of escape was tempered by the fact that I had been admitted to an unfashionable college on false pretences to read a subject I was eager to ditch. Doubts were banished, however, during an idyllic three months spent guiding mountain hikers around the Welsh Black Mountains and Brecon Beacons.