11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

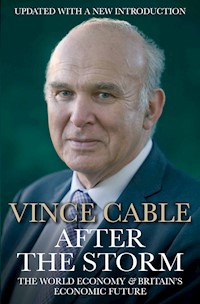

In this urgent and timely book, Vince Cable explains the causes of the world economic crisis and how we should respond to it. He shows that although the downturn is global, the complacency of the British government towards the huge 'bubble' in property prices and high levels of personal debt, combined with increasingly exotic trading within the financial markets, has left Britain badly exposed. This edition has been fully revised and updated to include Vince Cable's latest assessment of the recession.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

The Storm

Vince Cable is Member of Parliament for Twickenham and has been the Liberal Democrats’ chief economic spokesperson since 2003, having previously served as Chief Economist for Shell from 1995 to 1997. He was elected as Deputy Leader of the Liberal Democrats in March 2006 and was acting leader of the party prior to the election of Nick Clegg.

‘In a recession that has scorched the reputations of so many British politicians, one has grown in stature… This could easily have been an “I told you so” account, but Cable largely resists the temptation. Instead he offers a entertaining guide through the “Alice in Wonderland” financial world that evolved in the early years of the twenty-first century, and gives warning of the dangers that lie ahead if politicians draw the wrong conclusions.’ George Parker, Financial Times

‘Cable’s the star of Newsnight’s credit-crunch discussions, the go-to guy for a sagacious economics quote for broadsheets’ front pages, the man whom Tory Alan Duncan described as “the holy grail of economic comment these days”.’ Stuart Jeffries, Guardian

‘The pre-eminent domestic political voice on the financial crisis… Cable is excellent in distinguishing among policy responses to these imbalances, arguing that international action is needed to correct an international problem, and that the worst possible response would be a resort to protectionism and economic nationalism. He is exactly right.’ Oliver Kamm, The Times

‘Vince Cable is the parliamentarian who has been consistently the most prescient and thoughtful in his analysis of the credit crunch.’ John Kay, Financial Times

‘Everything a politician should be and everything most politicians are not.’ Jeff Prestridge, Mail on Sunday

‘Vince Cable is the only politician to emerge from the credit crunch a star… [The Storm] is a lucid guide to the present mess.’ Simon Jenkins, Sunday Times

‘Vince Cable is a phenomenon of our troubled times. By some measure, Mr Cable… is the most popular politician in Britain. In any putative government of national unity, he would be the default choice to be chancellor of the exchequer. What is all the more remarkable about Mr Cable’s improbable standing is that he is admired in almost equal measure by other politicians and a cynical public… A lone voice in a sea of complacency.’ Economist

‘Vince Cable has ideal qualifications for explaining the mess we’re in… Sane, compellingly justified… There has been a minor boom in credit crunch books since the recession but Cable’s provides one of the clearest explanations you’re likely to find of its causes… It’s Cable’s sense of history… as well as his prescience which makes his warnings about the future compelling… Commendably lucid and convincing.’ Caroline McGinn, Time Out

‘A study in moderation… Cable has always been ahead of the curve… The Storm covers the credit crisis in full, explaining what went wrong and sketching out possible remedies.’ Tim Harford, Management Today

‘The man who gives politicians a good name.’ Rory Bremner

Copyright

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This fully revised and updated paperback edition published in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Vincent Cable, 2009, 2010

The moral right of Vincent Cable to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-84887-058-1

Contents

Cover

The Storm

Copyright

Introduction

Chapter 1 - Trouble on the Tyne

Chapter 2 - The Great Credit Contraction

Chapter 3 - The Latest, or Last, Oil Shock?

Chapter 4 - The Resurrection of Malthus

Chapter 5 - The Awkward Newcomers

Chapter 6 - The Reaction, the Reactionaries and the Response

Chapter 7 - The Future: A Road Map

Postscript

Bibliographic Note

Acknowledgements

Index

Introduction

For the best part of sixty years the world has enjoyed a remarkable period of apparently ever expanding production, rising living standards and integration across frontiers. The clichés surrounding globalization are tediously predictable. The End of History. The End of Geography. Booming trade and foreign investment. A technological revolution resulting in cross-border communications of unprecedented speed. Financial markets able to transmit vast sums of money across national frontiers at the click of a switch. Industrial growth reaching new records. Mass tourism and migration. Rapidly emerging markets.

In the wake of the international banking crisis and the recession that has followed it, the inexorable suddenly looks uncertain. Hubris has given way to nemesis. Panic and the collapse of apparently secure financial institutions have reawakened long-dormant fears about the stability and sustainability of what seemed to be unstop pable, foolproof, historical forces of economic expansion. History teaches us, moreover, that individual and collective stupidity, greed and complacency act as powerful countervailing forces to what seems like unstoppable progress.

The late nineteenth century offered – at least for those parts of the world experiencing economic and technological take-off – a comparable period of growth and successful ‘globalization’. And then, things went horribly wrong. War, inflation, financial collapse, deflation, protectionism and another global war. Two generations later, we reassure ourselves that lessons have been learned, that the same mistakes will not be repeated, and that peaceful international economic integration will not again be destroyed by government incompetence and atavistic nationalism. We hope.

That hope has rested on confidence that the past has been remembered and properly understood. Yet there is, in the present febrile atmosphere of financial and wider economic crisis, in other countries as well as our own, a collective amnesia, a preoccupation with the immediate future and frantic efforts to stave off the next disaster. So far at least, governments have shown a proper sense of urgency and a recognition that if they do not hang together they will hang separately. The two G20 meetings in 2009 showed an impressive degree of commitment to common solutions: maintaining monetary and fiscal stimulus, and improving financial regulation. But there are still influential voices, as in the 1930s, urging a retreat behind protective barricades and disowning the liberal economic system, which is the only one that we know actually works.

The three disastrous decades from 1914 to 1945 have provided, for succeeding generations of policy makers, a set of lessons on what to avoid. These lessons were embedded in the process of post-war reconstruction under the political leadership of the USA and the intellectual leadership of Maynard Keynes and his disciples. Pre-eminent among them is a set of rules and institutions to prevent conflict, economic as well as political. The GATT (later the WTO), the Bretton Woods institutions and, in Europe, the Common Market, all had the objective of preventing a destructive cycle of ‘beggar my neighbour’ economics, and a commitment to liberalizing trade and capital flows within a set of agreed rules. The emergence later of new collective problems, such as global environmental threats, has reinforced this sense of cooperation as a public good.

A second and related aim was to ensure that, unlike pre-war Japan and Germany, emerging economic powers could achieve their aspirations for development through assimilation into democratic and market-based economic arrangements. The EU has been successful in relation to southern and then eastern Europe, and the United States has taken the lead in embracing the newly industrializing countries of east and south-east Asia as well as Latin America. But the European Union is struggling with the bigger challenges of Turkey and the former Soviet Union. Russia is retreating from the limited degree of integration achieved through the G8. India played a leading role in the collapse of the WTO negotiations. And the rapid emergence and only partial acceptance of China as an economic and political superpower lie at the heart of current global financial instability. Over the last year there has been a tacit acceptance that China is indeed the second superpower and that the other major emerging economies have to be at the top table. But there are serious potential tensions.

A further set of lessons arising from the post-war settlement related to the respective roles of the state and the market in successful modern economies.

There has, of course, been vigorous debate about the size and scope of the public sector. But it has been a central tenet of post-war economic policy, at least in the West and increasingly in emerging-market economies, that it is the job of government to facilitate the workings of open, capitalist economies: countering cycles of inflation and unemployment through macroeconomic management; providing safety nets through welfare states of varying generosity; and regulating markets where there are egregious failures.

In the last two decades the pendulum swung, particularly in the Anglo-Saxon world, towards deregulation. This appeared to have borne fruit in accelerating growth and widening opportunities for hundreds of millions of people in the rich and poor worlds. Yet the proclamation in the 1990s of ‘the end of history’, though rightly acknowledging the triumph of liberal systems, was hubristic and premature. It prejudged that governments would avoid or, at the very least, deal successfully with challenges such as the present combination of a systemic crisis in the financial system, price shocks, cyclical downturn and painful structural adjustment: The Storm.

The response of governments has so far been decisive and pragmatic. The right-wing Bush administration swallowed its ideological scruples and nationalized key financial institutions. Fiscally conservative governments, like the Germans, accepted the case for deficit financing. In an emergency, only governments had the range of powers to prevent a catastrophe. What is not yet clear is whether there will now be a fundamental rethinking of the respective roles of the state and markets, particularly financial markets, or whether the storm will simply be seen as an alarming, but temporary, interruption of ‘business as usual’.

The main focus of attention has been on a financial crisis centring on the banking system, the worst in scale and scope since the inter-war period. But there have been other, inter acting forces of instability. One of the currents feeding the storm has been a severe price shock: a sharp increase – partially reversed, at least for a while – in the prices of energy, raw materials and food. Much of the recent commentary has been cast in apocalyptic terms. The End of Oil. Malthusian Famine. Or, more generally, a reassertion of the ‘Limits to Growth’ thinking that flowered briefly in the 1970s. The collapse in commodity prices of late 2008 made these hyperbolic assertions look very dated, even ridiculous. But we are reminded nonetheless of the high level of instability in markets for commodities as well as financial products. And the reversal of the price collapse in mid-2009, with crude oil prices in particular rising again strongly with the prospect of renewed growth, especially in Asia, is a salutary reminder of the potential for further shocks ahead.

Arguably, the latest shock is the sixth since the Napoleonic Wars, when a period of economic expansion and disrupted trade and production sent the prices of food and industrial raw materials through the roof. There were similar episodes in the 1850s, coinciding with the Crimean War; at the turn of the nineteenth century; and in the early 1970s, when we experienced the first oil shock. Each of these episodes was, of course, unique, complex and painful in different ways. But we now know from experience what happens when world economic growth outstrips natural resource capacity. Prices explode and then subside as a new balance is established. Experience shows that governments can take sensible steps to mitigate the impact of commodity price shocks, but these do not include a retreat into autarky, even the mild Gallic version that manifests itself as farm protection. There is a risk that recent talk of ‘food security’ or ‘energy security’ presages precisely such a retreat.

The commodity price shock coincided in Britain, the USA, Spain and elsewhere with the creation, and now the bursting, of a bubble in the housing market. Indeed, the two things are probably linked through the same process of monetary expansion and contraction. But in addition, a new generation of home buyers, property investors and builders had persuaded itself that prices only ever go up, and that property was a guaranteed way to accumulate wealth. All historical experience should have taught us otherwise. There were regular building cycles in the UK throughout the eighteenth century, which were measured by historians as having an average of sixteen years from peak to peak, with continuing boom and bust cycles in the nineteenth century.

There is room for debate about the precise speed of the metronome, but a contemporary analyst, Fred Harrison, looking at the twentieth century has come up with a figure of nineteen years. And throughout modern economic history, the bursting of property bubbles has been one of the key trigger factors leading to earlier periods of recession: Britain in the 1990s; Japan at the same time and for longer; and now the USA and the UK, again. By now, governments should have worked out how to recognize and anticipate these bubbles, and, at least, deal with them in a rational manner. Yet the British and American governments are treating the problem as if it were being encountered for the first time. Moreoever, their instinctive reaction to deflation in commercial and domestic property prices has been to reinflate the markets. Any sign that the fall in house prices is being arrested is treated as a triumph and proof of recovery, even though it merely provides yet another fix, feeding the drug habit of property speculation.

The bursting of the house price bubble has been linked in turn to the so-called ‘credit crunch’, around which much of this book centres. Bank credit has been drastically curtailed in the wake of a collapse of confidence in the financial system. Markets have become fearful of contamination by bad debt, originating in US sub-prime mortgages, but now more widely diffused. The idea that financial markets are prone to excess, instability and panic is hardly new. The experience has been endlessly repeated throughout history. If we go back to John Stuart Mill, his analysis of irrational market expectations, based on a dramatic financial crisis in 1824–6 (and earlier events in 1712, 1784, 1793, 1810–11, 1814–15 and 1819), describes very precisely what happens when a ‘frenzy’ of ‘over-trading’ leads to a cycle of intense speculation, crisis and depression: ‘the failure of a few great commercial houses occasions the ruin of many of their numerous creditors. A general alarm ensues and an entire stop is put for the time being to all dealings upon credit: many persons are thus deprived of their usual accommodation and are unable to continue their business.’

Today, illiquid small businesses, and people trying unsuccessfully to remortgage their houses, will know exactly what Mill meant by the loss of ‘the usual accommodation’ by their once-friendly local bank managers. That earlier crisis was eventually stopped by borrowing money from France and by distributing a stash of old banknotes found to have been hidden away in the Bank of England. Today’s crisis is very much more complicated, but has the same basic architecture.

The history of financial bubbles should now be well understood. However, successive generations of financiers and investors have deluded themselves that they have, at last, found a foolproof way to manufacture riches without undue exertion: tulips in the seventeenth century; South Sea stocks in the eighteenth; various manias over emerging markets in the nineteenth; through to Wall Street in the 1920s. Then, more recently, there has been Latin American sovereign debt in the 1970s, Japanese land in the 1980s, British and Scandinavian housing in the 1980s (again), the Asian Tigers in the mid-1990s, new communications technology in the late 1990s, as well as our latest excitements.

A generation ago, Hyman Minsky described the mechanisms by which financial markets regularly overreach themselves, through excessive leverage, excessive risk-taking, greed and folly, leading to panic and then to ‘revulsion’: the stopping of credit. He would have recognized the contemporary commentators, bankers and politicians who, as with each preceding generation, have solemnly asserted that the world has changed and financial crises have become less likely, thanks to new technology and their own collective cleverness. Of course, they have not. And it is precisely the high level of technological sophistication and international economic integration that makes the recurrence of financial mania and crashes now so far-reaching and worrying.

I start with the past, since it reminds us that, whatever the contemporary uncertainties, there are lessons to be learned from what has gone before. This does not mean that I am a deterministic fatalist. Every stock exchange crash and banking crisis does not need to be followed by a Great Depression. Every burst property market bubble does not need to be followed by a Japanese decade of stagnation. Every boom in food prices does not mean that poor people should go hungry. There are better and worse ways of dealing with these problems, and hopefully historical perspective and comparative experience should help us to find the better ways.

It is especially important to reflect on the wider historical context, since the current combination of circumstances is particularly dangerous and potentially very destructive. The management of a collapsing housing market combined with a severe crisis of confidence in financial markets and institutions, as in the USA and the UK, would be difficult at the best of times. But, coincidentally, policy has been complicated by the need to respond to an inflationary commodity price shock, particularly in oil (and gas). And the commodity price shock originated with booming demand in emerging countries, led by China, whose economies are no longer dominated by the Western world and which are only tenuously integrated into the rules and institutions overseeing the world economy. Indeed, there is a plausible argument, discussed in detail in chapter 4, that China’s emergence, and the imbalance in trade and in domestic savings and investment between the USA and China, explain the financial bubbles of this century. The unifying thread of common interest is being frayed to breaking point, as we have seen with the collapse of the world trade talks and the attempts being made to blame the current crisis on American self-indulgent weakness or manipulative Chinese Communist authorities.

Yet if there is one lesson above all to be learned from historical experience, it is that nothing is more beguiling or more destructive than the siren voices of nationalism and its contemporary variants. Inter-war fascism has disappeared, but there are more subtle voices seeking to scapegoat foreigners, especially yellow and brown ones, or migrant workers in our midst, or else setting out a protectionist programme in the name of food or job or energy security. Less potent, but also dangerous, are those who, under a red flag – and sometimes under a green flag – work to destroy the liberal economic order and suppress markets and capitalism altogether.

This conjuncture of extreme events and an increasingly hostile political environment has been described as a ‘perfect storm’. This short book tries to describe how that storm originated and where it might lead.

Economic storms, like those in nature, come and go. They cannot be abolished. But, as with hurricanes and typhoons, they can be anticipated and planned for and a well-coordinated emergency response, involving international cooperation, can mitigate the misery. They also test out the underlying seaworthiness of the vessels of state. The fleet has been plying a gentle swell for some years and making impressive progress. But big waves have already exposed some weaknesses. SS Britannia, said to be unsinkable, has sprung a serious leak, and the vast supertanker USA is listing badly. Passengers and crews have noticed that most of the life rafts are reserved for those in First Class. Extraordinary seamanship has kept most of the fleet afloat, however; and the big Chinese and Indian container ships managed to keep out of the eye of the storm. How many ships will finally make it back to port in good order after the storm is, however, still in doubt.

1

Trouble on the Tyne

On 13 September 2007, exceptionally long queues started to form outside branches of the Northern Rock bank across Britain. They were not queuing to pay their bills or to talk to the bank manager about a new loan. They were frightened. They wanted to withdraw their savings. The Bank of England had announced that it was supporting the bank, which was in financial difficulties. Depositors, far from being reassured, were alarmed. And as the television broadcast pictures of worried savers queuing to take out their money, others joined them. On one day £1 billion was withdrawn. A few days later, the panic ended when the Chancellor of the Exchequer fully guaranteed all the bank’s deposits. But Britain’s financial establishment had been shaken to the core. Britain had experienced its first ‘run’ on a bank since Overend Gurney in 1866.

A country that prided itself on being in the forefront of financial innovation and sophistication had been shamed by the kind of disaster normally experienced in the most primitive banking systems. The only visual images most British people had of banking panics were television pictures of bewildered and angry Russian babushkas impoverished by pyramid-selling schemes disguised as banks in the chaotic aftermath of communism, or ancient black and white photographs of Mittel-Europeans desperately trying to force the doors of imposing but barricaded buildings in the 1920s. But this was Britain in the twenty-first century!

For those not caught up in the panic there was a collective national embarrassment, like that experienced when Heathrow Airport’s Terminal 5 didn’t work or when a national sports team is humiliated. But there was a deeper anxiety when it gradually emerged that those managing an economy built in substantial measure on success in financial services had no effective system for protecting bank deposits, no set of principles governing bank failure and no clear idea what the mantra of ‘lender of last resort’ actually meant. It was a little like discovering that one of the country’s leading obstetricians didn’t have the first idea how to effect the delivery of a large baby because all his experience had been with small ones.

The full saga of Northern Rock has been well described elsewhere and I do not need to repeat the story, even though I was involved in it as a politician. The reason why Northern Rock was important in the wider context was not merely that it exposed the inadequacy of regulation and regulators, but that it was the first major institutional victim of a global banking crisis and the credit crunch. (Arguably, BNP–Paribas was hit a few weeks earlier and had closed two of its funds, and HSBC had, with some prescience, warned of large losses on US sub-prime lending some six months before – but it was Northern Rock that brought home, very publicly, the existence of a serious banking problem.)

The Rock had once been a highly regarded, Newcastle-based building society, with a long-standing reputation for financial prudence and a strong commitment to its Tyneside community. Its origins lay in the tradition of Victorian self-help which produced friendly societies and other mutual institutions – owned collectively by those who deposited money with them – channelling savings into mortgage lending and other investments. The Conservative government legislated for the demutualization of building societies as part of a wider deregulation of financial markets, in the belief that access to shareholders and freedom from traditional restraints would permit the societies to expand more rapidly and to compete directly with banks. I was one of those who campaigned at the time to stop demutualization, on the grounds that the traditional mutual model offered something different, and more financially attractive to investors and borrowers, from the banks. A decade later demutualization was, effectively, stopped. But Northern Rock had already escaped the constraints of mutuality in 1997, following the Abbey National, the Halifax and others.

When it converted from a mutual to a commercial bank, it initially sought to maintain its community focus, and the new PLC was launched alongside a charitable foundation with a guaranteed share of the bank’s profits. The foundation has subsequently done much valued work in the north of England. But the management team, led from 2001 by Mr Adam Applegarth, had bigger ambitions for the bank – and themselves – than remaining as a small to middle-ranking player in the banking industry, known to the public mainly for its sponsorship of Newcastle United. They hatched an ambitious plan to capture a lion’s share of the UK mortgage market. There were two problems. The first was how to raise the money to lend, since building societies traditionally accumulated funding by the slow process of attracting deposits. The second was how to persuade house buyers to take mortgages from Northern Rock rather than their competitors. They hit upon an audacious business plan designed to solve both problems.

Funds were to be raised not from depositors but from mortgage-backed securities. There was an appetite in financial markets for packages of mortgages sold on by banks to other institutions through wholesale markets in the City of London. Banks have long augmented their resources by market borrowing (one reason why they have been able to expand faster than the more conservative, mutual building societies), and in the last decade there has been a rapid growth in this new, more sophisticated form of borrowing, known as ‘securitization’. But Northern Rock took borrowing to extremes; it raised 75 per cent of its mortgage-lending funds from wholesale markets, whereas a more conservative bank such as Lloyds TSB raised only 25 per cent, with the rest coming from deposits. Northern Rock saw securitization as a way of rapidly expanding its market share. Then, to attract new business, Northern Rock pushed out the boundaries of what the industry regarded as prudent lending. The traditional mortgage loan, at most 90–95 per cent of the value of a property and up to three times the borrower’s income, was already looking rather old-fashioned in the competitive but booming mortgage market around the turn of the century. Northern Rock was willing to go further than its competitors. There were 125 per cent ‘Together’ mortgages: that is, loans of 25 per cent more than the value of a house (in the form of a 95 per cent mortgage plus a 30 per cent top-up loan). In a world of ever increasing house prices, borrowers were assured that their property would soon be worth more than their debt. Loans were advanced on the basis of double the traditional three times income. The mortgages were sold with evangelical zeal, as part of a process of helping poor, working-class families to enjoy the freedom and inevitable capital gains of home ownership. Other banks followed suit in what was a very competitive market – precisely as the Conservative demutualizers had hoped.

The strategy worked, for a while. Share prices soared. Mr Applegarth acquired fast cars and a castle from his share of the profits. According to the News of the World, a mistress was rewarded with five mortgages and a property empire. In the marketplace, Northern Rock doubled its share of mortgage lending over three years; it held 20 per cent of the UK market (net of repayments) in the first half of 2007, giving it the largest share of new mortgages. It looked too good to be true – and it was. There was increasing critical comment in the financial press. Shrewd observers noticed that Mr Applegarth had quietly disposed of a large chunk of his personal shareholding. Shareholders picked up on the worrying reports, and the share price slid from a peak of £12 in February 2007 to around £8 in June after a profit warning, and then to £2 in the September ‘run’. One crucially important body did not respond to these concerns: the financial regulator, the FSA, which to the end remained publicly supportive of Northern Rock’s business model and did little to avert the coming disaster. Indeed, in July 2007 it even authorized a special dividend from the bank’s capital.

In September the model collapsed, in the wake of the decline of the sub-prime lending market in the USA. Northern Rock was the closest UK imitator of the US sub-prime lenders whose ‘ninja’ loans – to those with no income, no job and no assets – were the source of rumours of defaults. Since so much sub-prime lending had been securitized, there was a wider collapse of confidence in mortgage-backed assets, which, it emerged, were often ‘contaminated’ by bad debts which were difficult to trace. The market dried up and Northern Rock was no longer able to raise funds to support its operations.

The process by which the Rock was then rescued and, six months later, nationalized, is a tangled and complex story. There were, however, amid the detail, two important issues of principle. The first was the need to strike the right balance between the perceived risk of creating a damaging shock to the whole banking system, if one bank were allowed to go bust, and the danger of moral hazard, if foolish and dangerous behaviour were to be rewarded by a bail-out. I shall pursue the wider ramifications of this issue in the next chapter. Suffice it to say that, having initially emphasized the latter concern, moral hazard, the Governor of the Bank of England was then prevailed upon to undertake a rescue.

The second issue was how to strike the right balance between public-sector and private-sector risk and reward as a result of the rescue operation. After protracted and expensive delays in order to try to secure a ‘private-sector solution’ – which, in the eyes of critics, including the author, would have ‘nationalized risk and privatized profit’ – the government nationalized the company, effectively expropriating the shareholders.

Although it was only a relatively small regional bank, Northern Rock forms a central part of my story because it was the small hinge on which the British economy swung. It opened the door to the credit crunch and influenced the wider international financial markets. Its extreme mortgage-lending practices marked the outer limit of the home-lending boom, which is now bursting. And, towards the end of 2009, the government was seeking to split Northern Rock into a ‘good’ bank and ‘bad’ bank as a prototype for the return of banks to the private sector.