Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

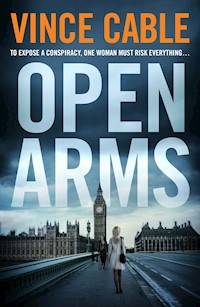

Kate Thompson - glamorous housewife-turned-MP - surprises everyone with her meteoric rise at Westminster. When Kate is sent as a trade minister to India, she hopes it will be her moment to shine. But, embroiled in a personal scandal, she gets drawn into a dangerous world of corruption and political intrigue... Billionaire Deepak Parrikar - head of an Indian arms technology company - is magnetically drawn to the beautiful British minister. But while their relationship deepens, India's hostilities with Pakistan reach boiling point, causing more than just business and politics to collide. In the race to prevent disaster, can their conflicting loyalties survive being tested to the limit? Open Arms is an explosive thriller which circles from Whitehall to the slums of Mumbai. Cable's sweeping tale combines unrivalled political detail with international intrigue, desire, and the quest for power. An electrifying debut.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Chapter 1: The Body

Chapter 2: The Candidate

Chapter 3: The Guard

Chapter 4: The Minister

Chapter 5: Bharat Bombay

Chapter 6: The Visit

Chapter 7: The Return

Chapter 8: Trishul

Chapter 9: The Riot

Chapter 10: The Scandal

Chapter 11: The Informer

Chapter 12: Escalation

Chapter 13: The Abduction

Chapter 14: Rehabilitation

Chapter 15: The Trade Envoy

Chapter 16: The Trainee

Chapter 17: The Exhibition

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

OPENARMS

CHAPTER 1

THE BODY

Reuters, 7 June 2019:

Indian sources report a border incident on the Line of Control in Kashmir. Several Indian jawans (soldiers) and infiltrators were reported dead. A defence ministry spokesman said that terrorists from the militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba had been intercepted crossing the border. He warned that under India’s Cold Start doctrine, Pakistan could expect a rapid military response if its government was found to be implicated.

The stinking rivulet was part bathroom, part laundry, part sewer and part rubbish tip, servicing the needs of a city within a city. But for Ravi it was an aquatic adventure playground. Those not acquainted with the sights and smells of the baasti would have grimaced at the tannery waste and turds and dead dogs of this slum. But he was endlessly absorbed by the stately progress downstream of his flotilla of boats made from twigs, cans and bottles on their way through swampland to Mumbai harbour and thence to the Indian Ocean.

That morning his mother had risen early to be ahead of the queue performing their bodily functions and washing at the stream. There was a healthy flow swollen by heavy overnight rain and Ravi’s attention was caught by a bundle of clothes trapped under a fallen tree, brought down by the rainstorm. This time of year produced a rich haul of driftwood, cans and plastic bottles to augment his merchant navy. He saw the potential of fabric for his sailing ships and with the help of a stick he managed to free the clothes until they floated closer to his harbour, a broken plastic frame that had so far escaped the attention of the boys scavenging for material to recycle. As he pulled on his catch he realised that it was bulkier than a bundle of clothes, and belonged to a man. This wasn’t his first corpse but this one lacked hands and feet and the gaping eyes carried, even in death, the look of terror. His scream had the early morning bathers rushing to examine his discovery.

Had Deepak Parrikar been interested in these happenings a little over a mile away he could have seen them with the help of a telescope from the top floor of Parrikar House where he was fielding an early morning round of calls.

Dharavi, with its million or more inhabitants, can claim to be Asia’s largest slum and it sits wedged between a major highway to the east, serving downtown Mumbai, and the seafront residences of Mahim Bay to the west, with fashionable Bandra to the north and the even more fashionable hilly area to the south where Parrikar House was located. But it was a place of which Deepak knew little and had never visited. And of the township of thousands of slum dwellers, where Ravi and his mother lived, between Dharavi and the middle class suburb of Chembur further to the east, he knew absolutely nothing. Yet this corner of Mumbai had a distinction: the World Health Organization had designated it one of the most polluted places on earth. Such a status was earned not just by the organically rich collection of bacteria in its water courses – for which any prize would have to be shared with many other sites in the city – but by a uniquely toxic soup of airborne, inorganic matter, a blend of traffic-generated particulates and the vaporised by-products of an ancient chemical plant, which Deepak’s father owned.

Deepak had long been able to filter out of his consciousness the sights, sounds and smells of India’s poor. It had once been necessary to apologise to overseas business visitors for the unpleasantness of the drive from the airport. But a new highway, partly built on stilts across the sea from downtown Mumbai en route to the new international airport, bypassed the more sordid and congested districts. He was able to concentrate single-mindedly on his business and the web of interlocking interests that he had spun, stretching from California to Singapore via London, Munich and Tel Aviv. The only smell drifting across his desk was the perfume of his PA, ‘Bunty’ Bomani, bought for her on a visit to Paris and now intermingling with his own expensive aftershave. Outside the large windows the sky had cleared after the monsoon storm the previous evening and the usual cloud of dust and smoke had dissipated to reveal the endless townscape of what, on some measures, was the world’s biggest city. The only sight to upset Deepak in the panoramic view was the grotesque, vulgar, multi-storey block of luxury apartments erected by one of his family’s main rivals, breaching every known principle of planning, let alone aesthetic design.

‘A call from your father, sir,’ said Bunty. He lay back in his comfortable office chair, legs on the desk, tie askew, and in his shirtsleeves, with the jacket of his exquisite, hand-sewn suit lying on the floor. ‘How’s Mummy-ji?’ he asked, switching to Hindi for his father’s benefit. ‘How’s her sciatica? Have you got rid of that good-for-nothing doctor yet? Charges you the earth. Useless. Quack. Absolutely hopeless. Ancient Tamil remedies! Nonsense! I told you to try the physiotherapist at the clinic on Dr Merchant’s Road. He has sorted out a lot of our friends’ back problems.’ And so on, for the statutory five minutes until his father switched the conversation to politics, then business, or the other way round, since they usually came to the same thing.

‘I spoke to my old friend Vikram, number three in the ruling party High Command,’ Parrikar Senior explained. ‘Sensible man, like the PM. Not one of these fanatical, temple Hindu types. He thanked me for our generous contribution to party funds. They know I used to back Congress and was close to Madam herself. But we are no longer outcasts. The PM likes the sound of our avionics operation, also. He may visit your factory to see India’s high tech manufacturing. He understands that the country needs to develop with our overseas partners. The government knows all about the technology being developed in Pulsar, our partner company in the UK, and is keen to bring it to India. No more stupid “Swadeshi” talk about “self-sufficient” India, reinventing the wheel.’

‘But Daddy-ji, where are we with this air force contract? We keep being promised. In the press ministers continue to say India has finally agreed to buy aircraft from the French – Dassault – not Eurofighter. Our British business partners are saying that India can only get access to the UK avionics technology if the air force buys Eurofighter.’

‘I know. Vikram says don’t believe what you read in the press. The PM understands. He has to respect procurement rules after all that fuss around the Gandhi family and Bofors, and other scandals. He wants clean government. Things have to be done by the book. So it will take some time to change things. However, the British are sending a ministerial delegation to negotiate in Delhi. They may come here also to visit the factory. Check us out. The British have left Europe and want to trade with us. The PM thinks they are beggars who can’t be choosers.’

The deal centred on the growing reputation of Deepak’s company, in India and abroad, in the world of radar-based detection systems, used in the latest generation of jet fighters and in India’s embryonic anti-missile defence shield. The company’s origins lay in a century-old British firm, Smith & Smith, which had made weapons for the British Army in India. Several takeovers later it had become Pulsar but the link remained with its former Indian subsidiary, now renamed Parrikar Avionics after a burst of Indianisation by Mrs Gandhi in the 1970s. Parrikar Avionics added lustre to India’s new image of sophisticated technology companies in IT, pharmaceuticals, precision engineering and aerospace. It had been built up by Deepak over the last decade. But the inspiration, as well as the capital behind it and the original acquisition of a majority stake in the clapped-out engineering plant, came from Ganesh Parrikar, his father.

Parrikar had started life as a street urchin in what was then Bombay in newly independent India. It was literally a rags to riches story. His family, landless, low caste Hindus, were starving in one of Bihar’s periods of drought and, aged ten, he was packed off to a distant relative in Bombay. He never found the relative and had to survive on the streets. He did survive thanks to the kindness of strangers, a streak of ruthlessness and the immense good luck of sharing a pavement with another Bihari who was making his way in the world running errands for a developer building cheap housing for the expanding population north of downtown Bombay. Ganesh ran errands for the errand boy and acquired a tiny foothold in an industry in which he was to make his fortune. He progressed within half a century to becoming one of the city’s dollar billionaires. A few years earlier his wealth would have placed him in the exclusive pantheon of India’s business deities alongside the Birlas and Ambanis. But there were now dozens of billionaires, in so far as it was possible to measure wealth that was often hidden from the tax authorities and jealous relatives, dispersed internationally and embedded in family trusts of Byzantine complexity.

Ganesh Parrikar’s energy, guile and unfailing instinct for property market trends and turning points were only part of his success. No one could succeed, as he had done, without being integrated into the network of corrupt officials and politicians that operated at city and state level. Nothing could be achieved without the right palms being greased. Nor could he operate without the muscle of gangsters who, for a consideration, would clear a site of unwanted occupants and ensure that rents were fully paid on time. But as a good father and patriotic Indian, Parrikar then diversified into productive and legitimate businesses to secure a legacy for his three children.

He made a berth for his eldest, Deepak. Deepak had been sent, aged thirteen, to an expensive school in England followed by engineering at Cambridge and a PhD at Imperial, and from there to Harvard Business School and several years’ practical experience in the aerospace industry on the west coast of America. When he returned he was charged with building up a high-level tech business in civil and military aircraft electronics. This he had done successfully, starting with a collaboration to adapt Russian MiGs to Indian conditions and then improving quality management to become part of the supply chain of Boeing and Airbus. The company’s British partner, Pulsar, was also an invaluable source of technology and marketing contacts, though the Indian offshoot was beginning to outgrow its former parent.

In truth, Parrikar Avionics made little money, though it added lustre to the family’s image and India’s reputation for world class manufacturing. It also advertised good corporate governance, since Deepak was a crusader for the kind of wholesome, caring, visionary company advocated by his friends in California. But the reality behind the opaque family business accounts was less wholesome: the balance sheet depended on the inflating price of land, much of it acquired by dubious means, and the cash flow was boosted by rentals from innumerable shacks of the kind occupied by Ravi and his family.

Inspector Mankad was settling into a pile of paperwork, which flapped in the gusts of air from the fan on his desk, when the call came in that a body had been found in suspicious circumstances. He was required immediately. He groaned. The pile of paper would continue to grow and the call also required venturing out into the muggy, oppressive heat until another monsoon downpour gave some relief. A possible murder in one of the most squalid, fetid, overcrowded and volatile of Mumbai’s innumerable patches of slumland was not a glamorous assignment.

He straightened out his khaki uniform in front of a small mirror that nestled among his display of family photos; twirled his impressively long moustache modelled on a heroic Bollywood crime fighter; tightened his belt a notch or two to disguise a little better his prodigious paunch; and collected his even more overweight assistant, Sergeant Ghokale, to head for the waiting jeep. Both carried revolvers but they were ancient and probably didn’t work. Rather, the officers’ badge of authority and legitimate force was a thick bamboo cane, the lathi stick, which, from colonial times, had been used to intimidate crowds and dispense instant justice to troublemakers.

When they arrived at the scene of the crime, Inspector Mankad and Sergeant Ghokale pushed their way confidently through the swelling crowd towards the inanimate lump by the edge of the stream, now covered by a dirty cloth. The faces were suspicious, fearful: poor people who knew all about police beatings and extortion. They parted meekly for the officers, whose peaked caps radiated authority and whose stomachs, bulging over their belts, suggested a prosperous career in law enforcement.

The four-year-old Ravi who had made the discovery pointed to the body and Sergeant Ghokale tried to ingratiate himself with the crowd by patting the child on the head and hailing him as a budding policeman. But no one understood his Marathi language. So he turned to his superior officer, and said, after a very quick inspection of the mutilated, bullet-ridden corpse, ‘Sahib, gang killing. One less goonda to chase.’

‘I don’t know the face,’ replied his boss. ‘I know all their mugshots. Nice clothes. Businessman? Maybe a money man; managing their loot? Look in his pockets.’

Sergeant Ghokale did as he was told. Inspector Mankad was a good boss, shared out any pickings, looked after his team. Ghokale fought back nausea from the stench around him and expertly picked his way over the wet, bloodstained clothes. ‘Nothing, Sahib. Clean. No ID.’

This could be awkward. Gang killing of unknown businessman. Kidnapping? Extortion? No one had been reported missing that fitted this man, as far as Mankad knew. He had survived and flourished in the Maharashtra police by bagging a regular crop of minor villains; generously sharing out any glory and financial rewards with superiors and subordinates; and knowing which cases to avoid, the political ones. Mankad calculated the risks. Gangland killings were dangerous. The top villains had friends in the state assembly and administration. Cases were mysteriously terminated. Police officers who showed too much curiosity could find themselves transferred to some fly-blown, poverty stricken country district. Now, with new faces after state elections, was especially dangerous. Mankad would have to be very careful.

But he was also a professional police officer. He may have played the game of brown envelopes and learnt how to swim in the shark infested seas of police politics. But he also had a medal for gallantry, and several highly commended awards, for doing his duty confronting armed criminals and protecting his team. He loathed the idea of gangsters going free.

As the officers moved to leave, Sergeant Ghokale grabbed hold of Ravi’s father who was standing protectively next to his celebrity son. ‘You. Witness. Come with me. Make statement.’ The man cowered and pleaded with the police officer not to take him: ‘Know nothing, Sahib.’ His Telugu language was totally incomprehensible to the policeman but the ripple of anger through the crowd gave the officer pause. They knew what would happen. The man would be taken to the police station, beaten and detained. His family would lose their meagre income: the two hundred rupees (three dollars) a day he earned from dangerous and exhausting labour on a building site, whenever there was work available. They would be told they needed to pay for food at the police station, to stop the beatings and then to stop a false statement being filed and then again to get him released. Every last rupee, and the limit of what the money lender would advance, would be squeezed out of them. And if they didn’t pay he would be charged as an accessory to the murder and the police station would be able to maintain its impressive hundred per cent clear-up rate for serious crime. Either way, the family would be destroyed and return to the bottom of the ladder, back into the extreme poverty from which they had just begun to ascend.

The tension was broken by a bark of command: ‘Ghokale. Leave it. We have work to do.’

As the officers retreated to their jeep, Mankad took a long look at the site. He tried to ignore the flies, the stench from the sewage pit and the curious crowd of children who were following them. He let his police training take over. One thing he noticed out of the ordinary was the pukka building on elevated land a quarter of a mile away, upstream from where the body had been found. Parked outside was a smart SUV that was unlikely to belong to the slum dwellers. And the flags flying from the building belonged to the Maharashtrian Shiv Sena party, an extreme nationalist outfit that, in the heyday of its founder, the late political cartoonist Bal Thackeray, ran the city. It was still a considerable political force where its cadres, operating from branch offices like the building nearby, were able to whip up communal feelings against outsiders: southerners, especially Tamils; northerners; Muslims. But all power corrupts and the pursuit of ethnic purity had long since taken second place to the spoils of extortion, smuggling, prostitution and other flourishing rackets. Mankad ordered Ghokale to drive the jeep a little further to make a note of the SUV’s registration number. But not too close.

CHAPTER 2

THE CANDIDATE

One year earlier: August 2018

Kate Thompson yawned with relief. The annual summer fete had produced record takings. Over five thousand pounds. The elderly ladies who made up the backbone of the Surrey Heights Conservative Association clucked with satisfaction. They disagreed, however, as to whether the big money spinner had been Kate’s Indian textiles, heavily discounted from her shop, or Stella’s cupcakes. The former verdict would align them with the glamorous wife of the local party’s sugar daddy. Loyalty to the latter would protect them from being flayed by the malicious, razor-edged tongue of the longstanding local party agent.

Appearances defined these respective factions. Kate was exceptionally tall, with long, comfortably unruly and naturally blonde hair; proud of her well-honed physique; and always shown to advantage in fashionable and expensive clothes. Stella’s army of elderly volunteers, with permed grey and white hair, were uniformly attired in dresses that reflected M&S fashions of a decade earlier.

Kate had never really felt she belonged to or understood the party, though her matching blue outfit and diligent work for The Cause might suggest otherwise. Her well-heeled, middle class parents – her late father had been a successful surgeon; her mother a pillar of the WI – had always voted Tory out of habit, though their broadly liberal views had sat uncomfortably with the content of their morning Telegraph. Kate had actually voted for Tony Blair in the noughties and at the last general election had turned up at the polling station sporting a large blue rosette and voted for the Lib Dem who seemed so much more interesting than the useless local MP. She had been further alienated by the Brexit vote, which she regarded as a disaster, one caused in part by the likes of Stella terrifying the pensioners of Surrey Heights by telling them that eighty million Turks were on their way. But a competent Prime Minister had arrived just in time to keep her in the party.

Still, she asked herself why on earth she was spending time here rather than with her daughters, her friends or her business. She had a seriously rich husband and what were rich husbands for if not to sign large cheques? His annual cheque to the association was worth at least ten times the amounts raised at this fundraiser, which had been planned over three months with as much detail as the Normandy landings. Unfortunately, he also had a tendency to treat his trophy wife as part of his successful property portfolio and had volunteered Kate’s services to the association without her knowledge or approval, leading to a considerable row in a marriage increasingly characterised by lows rather than highs.

Kate realised that money wasn’t really the point. The event was all about bonding, and nothing bonded the activists together more closely, short of an election, than gossip. An audible buzz rose and fell as Stella moved around like a bumble bee sucking nectar on its journey from stall to stall, while also injecting a little poison along the way. Stella was over fifty, blue rinse and twinset in imitation of her idol. She had a fathomless collection of stories from the highest sources – ‘absolutely true’ – about gay orgies, paedophile rings and fraud involving everybody she disliked. Kate had a firm policy of not being bitchy about other women, but those with acute hearing would have heard her mutter: ‘What an absolute cow.’

This year Stella was almost out of control, such was the pitch of her excitement. The rumour mill was working flat out, fed by the story that the veteran MP, Sir Terence Watts, was about to step down. His appearances in the constituency were infrequent and embarrassing. Today he had opened the fete, not an onerous feat, but had muffed his lines, got the name of the village wrong and thanked the wrong hostess for the loan of her beautiful garden. Perhaps he was distracted by the recent press revelations that he had seriously overclaimed for his parliamentary expenses, including three properties, one in Jamaica. He would be unlikely to survive the weekend.

Kate had never understood how he had managed to cling on like a limpet through a quarter of a century of inactivity. Her husband explained that the whips valued his uncritical loyalty and many older voters liked his military bearing and beautifully tailored three-piece suit worn in all weathers. Moreover, Stella had provided him with a formidable Praetorian Guard. Her devotion may have been grounded in an ancient passion but he was also the source of her local power. Now her loyalties had moved on and she was telling her geriatric army that the party of Mrs Thatcher, with the new female PM, needed more mature women MPs and fewer ‘bright young men’. Her profile of the ideal MP fitted herself perfectly. But had she been better at interpreting body language she would have realised that her enthusiasm was not widely shared.

The name on everyone’s lips was Jonathan Thompson, Kate’s husband: very rich, very handsome in a louche way, clever, capable, personable and well connected, a man who would inexorably rise to the top. Knowing her husband better than the party faithful, Kate could have added to the list of his attributes an insatiable appetite for serial philandering, a major deficit in emotional intelligence, and political convictions that mainly centred on the sanctity of his private property, particularly the parts of the property market that generated his fortune. She had, however, learnt to balance the bad with the good. But when she heard herself being addressed as the MP presumptive’s wife, something inside her rebelled.

She flushed with annoyance and struggled to concentrate against the competing claims of fussy customers, securing change for depleting floats, polite repartee and approaching rain clouds. Although she had never publicly articulated the thought, she had long felt that she would be a far better MP than many of the men she saw, and encountered, trying to do the job, not least the useless Sir Terence. The material comforts of life with Jonathan and family duties had dulled her ambition. But there was an ambitious woman waiting to emerge and this afternoon had stirred up what she had long suppressed. Her incoherent thoughts were crystallised when she was approached by one of the few local Conservatives she actually liked. Len Cooper was a long-serving county councillor, now the leader of the council. He was highly competent, unpretentious and modest: a successful local businessman in the building trade who believed in public service and practised it. They enjoyed a good friendship, uncomplicated by any emotional undertones. Her only discomfort was that at six foot without heels she towered over his small and totally spherical body. This didn’t seem to faze him; he was a man comfortable in his own skin and especially comfortable in the company of his equally spherical wife, Doris. As they started to talk they soon got around to the runners and riders and the short odds being offered on Jonathan. Len Cooper was non-committal but, after a long pause, said: ‘I am surprised that you haven’t considered standing yourself.’ Since Len didn’t do flattery, she took the comment seriously and was pleased as it reinforced a thought that had already crossed her mind.

It hadn’t crossed the mind of her husband, however. They had a rare evening at home together that night, as the girls were staying with family friends while competing in a gymkhana. Over dinner he set out the pros and cons of his own candidacy and various alternative scenarios in none of which Kate featured. He saw himself as the ideal candidate but had done the maths. They had three daughters at expensive schools; horses and paddock; a ‘cottage’ (actually a small château) in Burgundy; Kate’s Land Rover and his Maserati; the annual pilgrimage to the ski slopes at Klosters; membership of an exclusive golf club; and that was after cutting out some of the luxuries. An MP’s salary would reduce them to wretched poverty if he was forced into being a full-time MP – as the party High Command was now demanding – and to hand over the property business to his partners. Kate reminded him of the contribution she made from the profits on her business and could see a ‘p’ word forming on his lips – ‘pin money’ or ‘peanuts’ – before he stopped himself. He had a better idea: ‘The High Command is keen to find a bright young man. Ex-Oxford. Special adviser to the Foreign Secretary. The next David Cameron. Surrey Heights would be perfect.’ He – and possibly the High Command – seemed not to have noticed that posh boys were no longer the darlings of local constituency associations.

By now Kate was becoming seriously irritated. ‘If you don’t want the seat, why are you spending your money and my time bailing out the local Tories?’ she asked.

He thought for a while, hurt by his wife’s cynicism. ‘Because I care. The Labour Party has been taken over by Marxist-Leninist revolutionaries. If they get into power at the next election our heads will be on spikes. They hate us. The politics of envy.’

Kate shared the more conventional view reflected in the polls that the chances of Labour winning were roughly comparable to Elvis Presley being found on Mars. But this passionate outburst reminded her that while she and her husband agreed on some things – Remain being one – they disagreed on most others. She was privately relieved that her husband wasn’t going to be her next MP.

She then braced herself for a difficult exchange.

‘It may surprise you, Jonathan, but my name also came up in the chatter this afternoon.’

‘Who from?’

‘Never mind who. It did. And I am thinking about it.’

She knew him well enough to know that the words ‘don’t be ridiculous, woman’ were forming in his mind, but he knew her well enough not to utter them. He opted for soft soap instead.

‘You are a brilliant mother. Don’t the girls need our continued attention?’ (But apparently not his!) ‘Your business is doing well. Are you going to let it go?’ (This from someone who prided himself on not getting out of bed for a business deal worth under a million pounds.) And then the coup de grâce: ‘We have had our differences but you have been a wonderfully supportive wife. I need you.’ She cursed her lack of foresight in not having set up a tape recorder.

She kept going. ‘The children are no longer babies. There is a commuter train from the station down the road. I have a plan for my business. I can cope. And it might help you with your business to have an MP for a wife, close to the centre of power.’

He grunted in acknowledgement. ‘OK, you have a point. Let’s think about it.’ With that he disappeared to attend to his emails. Kate called after him: ‘I take that as a “yes”. Thank you, Jonathan.’ There was no reply. The ‘thank you’ was sincere. She would win the hearts and minds of the local association only as part of a happy, smiling family. And she would need Jonathan’s money.

The following morning, she rang Len Cooper. ‘I have been thinking about your suggestion. The answer is positive. Jonathan isn’t wild about it but he’s on board.’ Len expressed no surprise but took her through the practicalities. First, shortlisting by the executive committee. He would speak to Stella and assure her that her job was safe, but insist that she drop her ridiculous candidacy. He would tell HQ that after a quarter of a century of an absentee MP there had to be a strong local candidate. The ‘next Cameron’ should try elsewhere. And could they suggest a few other names of aspiring MPs who wanted experience of a selection meeting? ‘Then you have the hustings meeting in front of three or four hundred members. It will be a bit of an ordeal. Our Brexit militants will be out in force. You must put on a good show, but I know you will. A few of us will prep you properly.’

Reassured, Kate started to think about what she was letting herself in for. The girls were not babies, but not adults either. She had firmly resisted pressure from Jonathan to pack them off to a ‘character building’ boarding school (like his). She took mothering seriously, and it showed; the girls were close to each other and to her. Kate assembled them when they had returned from the gymkhana and had calmed down after telling her about their heroics in the saddle. When she explained her plans their faces lit up with excitement and they were soon texting their friends to tell them Mum was going to be the next Prime Minister. A good start.

Then there was her business: the product of twenty years’ hard work and a lot of emotional investment. On the surface it was just a fancy clothes and fabrics shop on the high street specialising in high-end Indian fashion. But it also housed a strongly growing internet sales operation. And behind it all was a small army of Indian suppliers: maybe a hundred women, mainly widows, whose livelihoods depended on being able to sell their beautiful, handcrafted embroidery to Yummy Mummies in Surrey. But as a Yummy Mummy herself she understood the market better than her competitors. Jonathan had been dismissive early on, seeing her shop as a hobby business to keep her out of mischief. But to be fair to him, he had put up some cash to help her acquire the freehold. And he had pulled some effective strings when an inflexible local bank manager tried to put her out of business during the credit crunch.

It had all started when she went off to India aged eighteen, with her girlfriend, Sasha, to ‘see the world’ in a gap year between leaving St Paul’s Girls’ School and going on to study medieval history at Oxford. Her parents were nervous but reassured that they were travelling as a pair. Shortly after arriving in India Sasha was laid low by Delhi Belly, which turned out to be a severe case of amoebic dysentery, and flew back home. Kate lied to her parents and told them she had teamed up with another girl and would stay. The truth was that she was utterly captivated by India. Walking around Old Delhi constantly assailed by new sounds, sights and smells, she felt as if a door was opening up to an utterly different world she needed to explore.

Kate’s academically stretching but chaste education at St Paul’s had equipped her with an impressive understanding of dynastic politics in the Plantagenet era but hadn’t educated her in the various species of predatory men. In Delhi’s coffee shops, in Connaught Circus frequented by Westerners, she bumped into a friendly Australian, Jack (or as she discovered later, he had contrived to bump into her). He was seriously scruffy with a tangled beard and unkempt long black hair and clearly hadn’t washed for some time. But beneath the grime he had an open, welcoming smile and a reassuring, generous manner. He listened sympathetically to her anxieties and adventures and offered – without, he hastened to add, any obligations – to let her tag along with him. Travelling would be safer. He explained that he was in search of true enlightenment, discovering his transcendental soul, and was finding in the poverty of India a genuine richness of spirit. His spiel was thoroughly convincing and Kate was entranced.

Needless to say, his search for enlightenment soon led to her bed, in the cheap and dirty hotels they passed through along the Gangetic plain. The experience was neither physically nor emotionally satisfying but Kate was persuaded that she was getting ever closer to her inner being. He also introduced her to pot, which made her violently sick and provided none of the mystical wonders she had read about. They finally parted company when he took her to an ashram presided over by a naked sadhu, His Holiness the Guru Aditya, who preached the renunciation of bodily needs but actively solicited sexual favours and money from his Western acolytes. Kate fled back to Delhi, alone.

She could hardly wait to get on the next plane home. But before leaving she headed into Delhi’s profusion of handicraft emporia to buy presents for family and friends. She was attracted to a modest stall offering exquisitely embroidered garments and furnishings – at modest fixed prices. She spent her remaining money and, as she left, the owner, Anjuli, ran after her in some distress explaining that she had accidentally overcharged. This novel experience led to a conversation and an invitation to visit her workshop, a room off an alley nearby, where a dozen women worked, barely pausing to greet her. An idea began to form that was later to become the basis for Kate’s business. The pair exchanged addresses; Kate placed an advance order for goods to sell to her friends; they worked out how she could send the money to India. Two decades later, she had established a flourishing high street and internet business on the back of Anjuli’s crafts, which never failed in quality, quantity or delivery. They won other customers including a leading UK fashion brand. And when Kate had last seen Anjuli she was a little greyer but, by now, a leading social entrepreneur whose network of cooperatives was an obligatory feature of development agency reports. Together they had achieved something. Kate was now ready to hand the running of her business to others and move on to a new challenge.

The Conservative Association hired a large hall to accommodate the five hundred members who wanted to attend the selection hustings. Kate had never spoken to a big meeting before and was extremely nervous despite intensive preparation and the presence of Jonathan and her daughters in the front row. She sensed that the meeting was cheering her on, though some of the questions were hostile. ‘What are you going to do about immigration?’ ‘… standing room only… overcrowded island… swamped’ etc. She struggled to reconcile these questions with the local village of five thousand souls whose immigrant population consisted of Mr Shah and his family at the post office and the largely invisible owner of the Chinese restaurant. She had been advised, however, not to appear too condescending but to show, at least, a willingness to listen to heartfelt concerns. Her unsound social liberalism on gay marriage lost a few votes. But it didn’t matter. She was overwhelmingly adopted on the first ballot.

Three months later the party machine swung into action for the general election, which the Prime Minister called early when her Brexit programme ran into serious trouble in parliament and before rising unemployment dented her popularity. Since the constituency had returned Conservatives with massive majorities, even in 1945 and 1997, there was little basis for anxiety.

Kate was required only to put in a few days’ work shaking hands and being photographed. The Tory machine did the rest. The sole ripple of controversy in the campaign was her initial refusal to put her family in front of the cameras when she worried that this old-fashioned public display of traditional family values might prove a hostage to fortune. Stella led the opposition, arguing that the members would not countenance such a display of metropolitan liberalism so soon after the demise of Sir Terence.

Such interest as her campaign excited centred on her appearance. Her height and figure would have qualified her to be a professional model. Her face was very handsome rather than conventionally beautiful, and with her naturally blonde hair, she had the classical good looks of a well-bred, upper middle class English family whence she came. All of this would have been reserved for the electors of Surrey Heights, had an earnest Labour shadow minister not chosen to enliven the election campaign with an attack on the ‘objectification of women’ by the right-wing media deterring talented young women from coming forward into public life. The press, which had been bored to death by the opposition leader’s lectures on the evils of capitalism, at last had a serious subject to get their teeth into. The Sun retaliated with a headline and two-page spread. Prominently featured was a photo of Kate taken half a lifetime earlier when she had tried modelling in her gap year, posing in a minimalist bikini. She was one of several ‘Gorgeous Girls’ who would be banished to an appalling Gulag if Manchester’s Madame Mao and her Loony Left Labour friends got within a million miles of Downing Street. Kate was rather relieved that the Sun was not more widely read in Surrey Heights.

8 June 2019

Air conditioning was an essential of life for Deepak Parrikar. Without it, office and home were intolerable. For his father it was an uncomfortable, alien distraction. His small office, downtown in the bazaar area around the old fort, relied on a noisy overhead fan. Bits of paper flapped under their weights as the fan revolved – that is, when it worked, downtown Mumbai being subject to ‘brownouts’ from time to time, the symptom of India’s creaking infrastructure. And the noise of the fan was competing with the cacophony outside: the rattling, squeaking, banging and scraping of vehicles being loaded and unloaded; the constant hooting of horns by moped, motorcycle and car drivers and, in a deeper register, from the boats plying the harbour; the barking of dogs; the cawing of crows; the plaintive whining of the beggars; and the shouting of street hawkers and hustlers. The senses were further assaulted by a heady cocktail of smells: richly scented garlands on the wall, diesel fumes, rotting food in the street, cooking oil, human waste, spices.

None of this could be heard or smelt in Parrikar House but this was where Parrikar Senior preferred to work. It wasn’t sentiment that kept him there. It was here, and in the chai shop on the corner, that his network of informers and confidants, business contacts and friendly officials could slip in and out quietly, like a colony of ants ferrying gossip, rumours and inside knowledge back to the nest. The stock exchange, the bullion market and the municipal offices were all nearby. Here he could keep up with, or ahead of, the markets in which he operated.

This morning, one of Parrikar Senior’s oldest associates was in his office: Mukund Das, flustered and sweating profusely in a safari suit that was at least one size too small.

‘We have a problem, Parrikar Sahib. Our Mr Patel has gone missing. He didn’t come home yesterday evening.’

‘Girlfriend?’

‘More serious, Sahib. A few days ago he had a visit from a couple of goondas. I recognised them: shooters; the Sheikh’s men. People we don’t mess with. Trouble. I asked what they had come about. Patel said: “Nothing. The usual shit. I told them to fuck themselves.” He didn’t want to say more. But I knew the reason: these goondas want protection to cover potential “accidents” on the site. We normally pay. No problem. But not Patel. He has high principles. Then, next day, he said he had had late night calls. Some goondas threatening him. He was frightened, very shaken. He planned to come and talk to you. Now he has gone. Mrs Patel telephoned to say he did not come home last night.’

The mystery did not last long. Parrikar Senior’s PA brought in the morning newspapers. On the front page of Bharat Bombay was a picture of a body. Unmistakably Mr Patel.

‘Exclusive’ is a valid claim for Mayfair’s Elizabethan Hotel. It is tucked away down a quiet, cobbled mews and never advertises, relying instead on a reputation for tasteful luxury and absolute discretion of the kind demanded by those among the world’s super-rich and powerful who prefer to stay out of the limelight. These qualities were especially valued by the Chairman of Global Analysis and Research when he needed to convene a meeting of his directors.

He was sprawled across a soft leather armchair in a private room in the bowels of the hotel sipping occasionally at the large tumbler of neat whisky beside him and giving his captive audience of three the benefits of his geopolitical world view. The lecture was delivered in the slowest of Cajun drawls and he could have been chewing the cud on the verandah of his eighteenth-century French mansion overlooking the swamp-lands of Louisiana. But his associates were careful not to let their attention wander too far. The Chairman’s brain moved a lot quicker than his speech. And there were crocodiles in his swamp.

‘Good news, colleagues. History is on our side. Good friends of our company are now in charge in the US and Russia. Islamic terrorists are in retreat. More and more customers are queuing up for our anti-missile technology and we are now the dominant supplier in parts of that market. Our external shareholders are delighted with the thirty per cent return we are giving them. And I hope you are all pleased with the size of your Cayman accounts. Let us drink to the future of Global.’ There was a growl of approval and glasses clinked.

‘Now, let us get down to business. Reports on our next project, please. Admiral?’

‘I am lining up the British company we have researched. No problems. My contacts in government will play ball.’

The Chairman paused, sensing overconfidence and seeing that the Admiral was rather flushed. He had brought class and an impressive contacts list to the company. But he was too fond of rum.

‘Are you sure? I need to be sure.’

After an awkward silence, the burly, crew-cut Orlov spoke up for his old friend. ‘The Admiral always delivers. Ever since we worked together in St Petersburg twenty-five years ago he has been as good as his word. And he is the only Britisher I have met who can drink Russians under the table.’ His belly-laugh proved infectious.

The Chairman swallowed his doubts. Orlov was a thug. But a reliable thug. And a man with almost unprecedented access to his old KGB chum in the Kremlin.

One member of the group remained silent and unsmiling. Dr Sanjivi Desai was slowly making his way through his favourite tipple: apple juice. He was a small man with a neat moustache, greying hair, a look of great intensity and a beautifully tailored suit of Indian design. His English was impeccable with slight Indian cadences and traces of an American accent. ‘There are uniquely promising opportunities in India. A competent government aligned with our values. Badly in need of what we have to offer.’

The Chairman had known Desai for a long time and trusted his judgement. ‘Good. Let us know how you get on.

‘Now, I have some news of my own. On medical advice I have decided to appoint a deputy Chair. Another American. Colonel Schwarz is recently retired from the Pentagon. Their top man on anti-missile defence. Close to the Trump people. A find. None of us are indispensable, including me.’

CHAPTER 3

THE GUARD

Twitter, 8 June 2019:

President Trump’s tweet after the regular six-monthly meeting between the Presidents of the US and the Russian Federation:

‘Good meeting with #Putin. Sorted #Europe and #MiddleEast. Biggest nuclear war risk India and Pakistan. nice people. #SAD!’

The dead of night was very dead. For the night watchman, sitting in a cubicle outside the front entrance of the factory, the challenge was to stay awake and carry out the few tasks he was paid the minimum wage to perform. In the months since Mehmet had been given the night shift outside the Pulsar factory he had seen a variety of urban foxes and stray dogs, two tramps, an illegal fly tipper and several couples doing what couples do in the back of cars when they think they are alone in a quiet corner of a sleeping industrial estate away from the neon lights. Silence was broken only by the distant hum of the M1.

It was a job nonetheless. Not quite the intellectual stimulus of his earlier job as professor of mathematics at the Eritrean Institute of Technology. But he was grateful to have been allowed to stay and work in the UK after he had escaped the mindless carnage on the battlefields separating Ethiopia and his native Eritrea and, then, as a disabled war veteran, and known dissident, had abandoned a harsh and insecure life under the dictatorship. As he surveyed the nocturnal tranquillity of the estate he endlessly replayed in his mind the events that had led him to this life of safety and excruciating boredom.

After being conscripted into the army and surviving a pointless war that left a hundred thousand dead on both sides, there followed a long trek, familiar to asylum seekers from the Horn of Africa, through Sudan and Egypt, the journey on a leaking, dangerously overcrowded boat across the Mediterranean followed by the trek to Calais, a month’s agonising wait in the Jungle and, after numerous attempts, entering the UK clinging to the chassis of a lorry. He had then been accepted as a refugee seeking asylum. Tedium and poor wages were now a small price to pay for freedom. Eventually he would get his Indefinite Leave to Remain and he had sketched out a long term route map, requalifying through the Open University, teaching and being reunited with his family.

Little was asked of him at work beyond monitoring CCTV footage of the perimeter, protected by a formidable fence with razor wire. He was also to check that the premises were empty before switching off the main lights and locking the entrance at 10pm. Occasionally research staff stayed late and he was to ensure that they were signed out and accounted for. The purpose of the factory was never explained to him – the supervisor had simply said Pulsar did ‘hush-hush’ things, something to do with the military. There was a secure area from which he was barred – only accessible by lift to a small number of pass holders. In an emergency he had access to a panic button; back-up security staff would arrive within five minutes. In his six months, alternating shifts with a Nigerian, it had not been needed.

At 2am that night he needed the toilet, which was beside the reception area. As he left the building he spotted a faint light under one of the doors to the main building: torchlight perhaps? He unlocked and opened the door. There was a brief, faint scuffling sound and then silence and darkness. Mehmet looked carefully in all the rooms accessible from the door. But nothing. He rechecked the ledger. No one officially in the building. He kept a careful eye on the building until morning – but no one appeared. He signed off in the morning: ‘Investigated possible intruder but no one found. Decided not to raise alarm.’ He looked back through the log book and saw that Osogo, the Nigerian, had made a similar note a few weeks earlier. He asked to speak to the head of security, who laughed it off: ‘Ghosts! You Africans have a very vivid imagination.’ Mehmet resented the security chief’s patronising manner and the rather phoney bonhomie he had displayed since their first meeting at the job interview. But he was not going to compromise his job or his immigration status by picking a quarrel. So he smiled deferentially, agreeing that Africans were indeed people with small brains and childlike fears.

While Mehmet left after his night duty and his encounter with ghosts, the CEO, Calum Mackie, was already in his office, preparing for an early morning call, looking over the papers from his safe first, and checking the relevant emails.

Mackie was a technological genius whose world-beating research in ultra-high frequency radio waves had found both commercially profitable and militarily useful applications. He had taken over Smith & Smith, the once great manufacturer of military equipment, when it ran aground. Renamed Pulsar, it retained a highly skilled workforce, some valuable patents and an excellent network of export outlets and overseas investments dating from the days of Empire. Calum rebuilt the business, strengthened by his inventions, and over the last ten years massively expanded exports to NATO countries and others for which he could get export licences. Like other successful British technology companies, his had struggled to raise capital to expand and he had been tempted to sell out to US competitors who were only too keen to get their hands on his technology. Indeed, the MOD was very anxious that the latest smart adaptations to his aircraft-borne missiles did not fall into the wrong hands. Fortunately for their peace of mind, and his, he had secured some American private equity investors who were willing to commit substantial sums, long term, without interfering, on expectation of exceptionally good returns, which he had, so far, delivered.

On the other end of the phone was his well-established link to government: Rear Admiral Jeremy Robertson-Smith, a military hero, UK plc’s arms salesman extraordinaire and now a freelance consultant operating on the blurred boundaries of business and state. A legend promoting UK defence sales (much of it made by his former employer), his fingerprints were all over a decade of successful defence deals, and many British companies, including Pulsar, were in his debt (as he was not slow to remind them).