3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

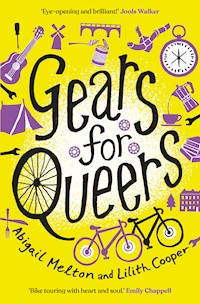

- Herausgeber: Sandstone Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Keen to see some of Europe, partners Abi (she/her) and Lili (they/them) get on their bikes and start pedalling.Along flat fens and up Swiss Alps, they will meet new friends and exorcise old demons as they push their bodies – and their relationship – to the limit.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Abigail Melton and Lilith Cooper are a queer couple who are artists, community organisers and service industry workers. Lili grew up cycling around Cambridge and, when they met, transplanted Abi’s desire to walk the world onto two wheels. This is their first book – born out of a series of vegan recipe zines from their first cycle tour. They live in Kirkcaldy, Fife.

First published in Great Britain by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Willow House

Stoneyfield Business Park

Inverness

IV2 7PA

Scotland

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright © Abigail Melton and Lilith Cooper 2020

Editor: K.A. Farrell

The moral right of Abigail Melton and Lilith Cooper to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Sandstone Press is committed to a sustainable future. This book is made from Forest Stewardship Council® certified paper.

ISBNe: 978-1-912240-97-5

Cover design by Jason Anscomb

Typeset by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Preface

Our friends and family met the announcement of our planned cycle tour with confusion and alarm. How could two people, routinely unable to leave the house for days on end, manage to cycle from Amsterdam to Spain?

When we left for the Netherlands in 2016, even we didn’t know the answer.

Neither of us had ever done anything like this before and we came at the cycle tour with very different experiences – Abi had never cycled more than the 20 minutes to and from work, while Lili had spent more time in psychiatric hospitals than away from their home town. When we boarded the ferry at Harwich, we had no idea how we were going to cope, what this tour would look like, or if we would enjoy it.

Writing this book has been more difficult than either of us imagined. We felt uncomfortable staking claim to the identity of ‘cyclists’ and struggled to feel our trip was legitimate. We spent hours scrolling Instagram, comparing ourselves to other cycle tourers who had completed their trips in a way we felt we hadn’t. We persevered because we didn’t want to perpetuate those narrow ideas of what cycle tours and cycle tourers looked like.

Cycling through the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and France for three months, we met only two sets of British cyclists, and yet these paths are just a short ferry ride away. As people become more interested in sustainable travel, we want to encourage people to access these amazing cycle routes, and we want cycle-touring culture in the UK to continue to grow. Visibility is only a small part of this. We need city planners, councils, transport bodies and the government to recognise and act on the demand for family-friendly, accessible cycle paths. We also need a cultural shift in attitudes to cyclists.

On the tour, we learnt some harsh lessons about taking up space on the road. We want this book to both take up space and hold space open for other accounts of bike touring or travelling that are too often silenced, minimised and marginalised. Both of us are privileged in ways that allow our voices to rise above many others in our communities. We have tried, in our account of the tour, to articulate the things that made this trip possible for us.

Lili is non-binary and is referred to with the gender-neutral pronouns they/them, which are used throughout the book.

Gears for Queers can be read by anyone, but it is written specifically for the queers, for other fat, disabled, trans, female, femme and non-binary people who are curious about bike touring. To queer something is to trouble boundaries, to question the divisions into binaries: success/failure, commuter/cyclist, mad/sane, travel/migrate, leave/remain. We hope the book does this too.

Take care and happy riding,

Lili and Abi

Gears for Queers

Day One, Amsterdam to Durgerdam

Abi and I left the hostel early, hauling our panniers one by one down the steep wooden stairs and depositing them on the damp alley cobblestones outside. I had spent the night lying on the top bunk, listening to drunken shouts and thunder while my mind raced.

Rounding the corner, I was relieved to see our bikes, Patti and Paula, had survived a night in the red-light district. Steel-framed, bought second-hand from Gumtree, they may not have looked like much, but over the months we’d spent fixing them up we’d fallen in love.

We wheeled the bikes over and rested them against the red-brick hostel wall. Slowly, the pile of bags was distributed across the two bikes. I heaved two large black pannier bags onto my rear rack. As I went to clip the two smaller front panniers the bike shuddered against the wall. I held my breath as it ground to a halt midway through falling, leaning dangerously to one side. I gingerly hooked the front bags on and attempted to right it. It was too heavy. Instead, I wrestled a large dry bag with my sleeping bag, a smaller one with our tent, my ukulele and a large hiking rucksack onto the top of the rear rack, securing them with bungee cords. The final flourish was a small fabric bag I attached to my crossbar.

I stood back and examined the result. Abi joined me with a look of trepidation.

‘We aren’t exactly streamlined,’ she commented.

‘We’ll be fine!’ I replied cheerily, silencing my own gnawing worry.

Abi and I emerged from the alley to join the rush of cyclists on the road up towards the train station. I still wasn’t used to riding a loaded touring bike; it was slow and bulky. Quick streams of bikes flowed around us on the cycle path. My arms started to ache from the effort of steadying my unwieldy handlebars.

We rode into the gaping mouth of a cycle tunnel beside Amsterdam Centraal Station. Fluorescent orange lights blinked overhead. We surfaced at the back of the station, clambered off our bikes and wheeled them onto the foot ferry. The small boat which crosses the old bay connecting Amsterdam with the sea was busy with morning traffic. I gripped the handlebars of my bike, my nails making crescent-shaped grooves in the grip tape, as the boat ploughed deep furrows into the water.

On the opposite shore, we followed the single road away from the ferry terminal. I patted my pocket containing the folded Google Maps printout of our route.

This was it. After six months of prepping and planning, Abi and I were actually riding our bikes in a whole different country. We weren’t cycling to work or the supermarket. We were travelling; we were cycle tourers.

‘This is the same bridge. Again.’ Abi was barely containing her frustration.

‘Eurgh,’ I grunted in response.

We’d been cycling in circles for nearly 40 minutes. It didn’t seem to matter what configuration of turns and paths we took, we always ended up here, at the same crossroads, looking at the same bridge. It was like a terrible Choose your own adventure storybook. The Google map was a useless page of squiggles and words. Maybe if I stared at it hard enough, it would start to make sense and match up with something, anything, around us.

‘Are you lost?’

I looked up to see the broad smile of a man, standing astride a heavy Dutch bike.

‘A bit,’ I conceded.

‘Very,’ Abi interjected.

I shot her a look; I hadn’t wanted to admit defeat.

‘Where are you heading?’ he asked, laughing.

‘Durgerdam.’

Abi’s dad had given us several pieces of advice before we left: don’t pet stray cats, watch out for bears and don’t trust strangers, especially men. I considered this as I rode beside Daan. We’d accepted his offer of a guide without hesitation.

‘I don’t think it’s such a bad thing,’ he was saying. ‘Maybe the Netherlands should be more independent too.’

We had left the UK in the wake of the EU referendum two months prior, and it seemed inevitable that it would be the first thing people wanted to talk about. What I thought about Brexit and what I felt about Brexit were two very different things. I could understand many of the reasons why people had voted Leave; I knew the EU wasn’t an uncomplicatedly ‘good’ thing; I could see how the referendum had come about. At the same time, I’d listened to my friends who had made Britain their home, temporarily or permanently, express fear, loss, alienation, confusion and worry. Abi and I felt part of a community that had been hurt in a way that was irreparable, and I was furious. I focused on the winding route through a small park.

‘I guess I just feel we will lose more than we could possibly gain.’ This felt a weak expression of my true sentiments.

‘You know where I want to go? Utah.’

This was not the direction I’d expected a conversation on Brexit to take.

‘All that wide, open space,’ Daan continued, ‘the freedom to do as you want.’

We travelled along broad suburban streets, before taking a sharp right down a narrow, cobbled path. We turned into a maze of industrial roads. I glanced behind me to check that Abi was still tailing us, concerned we were about to end up in some kind of Dutch Mormon warehouse complex. At the end of an alley we pulled to a halt at a T-junction, with a large, dark, stone church on the corner. Across the road from us, the tops of masts bobbed in the water. We were on the shore of Lake IJmeer.

‘Go straight along there,’ Daan gestured left, ‘and you will reach Durgerdam. Good luck.’

Fuelled by the fresh air and keen to shake the feeling of being lost, I sped along the shoreside as fast as the weight of my bike would allow. My wheels bounced along the uneven road. I tried to avoid the larger potholes but, distracted by a display of shells in a cottage window, the sails of boats or a glimpse of the sea, I would occasionally hit one, sending my panniers flying up and crashing down. I’d wince at the noise and resolve to pay more attention, until I found myself lost in the moment again.

The sign for the campsite came into view. I sprinted for the finish line, skidded my bike to a stop on the gravel drive and waited for Abi to catch up.

‘Have you come far today?’ the man at reception asked as he took my passport, assessing my sweaty face, legs splattered with mud, and a grin of achievement.

‘From Amsterdam.’

‘Oh, so not so bad.’

‘It took us two hours.’

He looked up from the paperwork. ‘How?’

I walked over to Abi with his laughter still audible. ‘We really need a map.’

Day Four, Amsterdam

After two days’ rest in the campsite, I confidently led Lili back along the shore, through the cobbled streets and into the city. Cycling into Amsterdam was simple now we knew the route. We flew through alleys, around tourists already drunk on cheap Dutch beer, and over countless bridges, following the marked cycle lanes which wove alongside every road and lane. Around us, bikes clung to any available railing, locked tight to form a multicoloured wall of metal along each canal. Some were abandoned carcasses, without wheels or seats, broken frames rusted red from time, stuck in their final resting place.

Narrow houses formed a patchwork of different shapes and colours beside the canal. All were a different style or height, the only similarity being the many large windows on each.

We parked our bikes outside a small coffee shop. I pushed through the crowds inside to an empty table nestled in a dark corner. Lili perched on a tiny wooden stool whilst I leant into the wall to avoid elbowing our neighbour.

‘Right, who’s going to do it?’ Lili asked me.

I looked beseechingly at Lili. I was hoping they would take the reins.

Lili read my cue. ‘Ok. What do we want?’

‘I dunno.’ I smiled gratefully. ‘Something that makes us happy? I don’t want to feel ill.’

Lili shuffled over to the busy counter at the back of the coffee shop to buy us a single joint.

I sat back and tried to relax. Smoking weed was not something I’d done often. My brain was taking great pleasure in reminding me of the one unfortunate incident at university when, catastrophically high, I’d eaten a whole family-sized quiche from my friend’s fridge then proceeded to vomit it all over the same friend’s bathroom suite. Still, when in Amsterdam …

Lili returned and placed a rolled joint onto the table. ‘It’s pure weed. I didn’t think tobacco was a good idea. The guy said to take it very, very slowly and only take one or two tokes.’

‘Ok, sounds good.’ I smiled nervously.

‘He also said we should stay here until we feel ok. Shall I get us some drinks?’

I nodded then lit the joint, inhaling deeply. I passed it to Lili who took a toke and then another. I took one more and extinguished it.

We sat for half an hour in the dim light of the coffee shop. I sipped my overpriced orange juice and repeatedly checked the time on the phone.

‘I’m not really feeling anything,’ Lili announced.

I wanted to get going and visit the Van Gogh museum. ‘Shall we have one more toke and then leave?’

The gloom of the coffee shop gave way to the blinding light of a summer’s day. I stumbled onto the pavement, unsteady on my feet, and pulled Lili’s hand in the direction of the Museumkwartier. The colours of the city were intensifying the more I stared, like someone had turned the contrast up on a TV screen. I looked at Lili who was giggling uncontrollably, and I immediately burst into a fit of laughter.

‘Nobody … knows … we’re … high,’ Lili gasped between breaths.

I nodded, desperately trying to stop laughing. Tears ran down my face. Luckily no one could see me; all their faces had disappeared into a blur.

The pavement fell away from me, and suddenly I was standing in the middle of the road. I rushed Lili to the other side and onto the opposite pavement. I looked around, my eyes would only focus in on the tiniest details, a discarded chewing gum wrapper, the second hand of a clock, the button on a jacket.

‘Abi, I’m not ok, I’m really not ok.’ Lili looked across to me, face contorted with fear. ‘We need sugar, we need sugar.’

I could barely hear them through the invisible bubble that had engulfed me. ‘I’m not doing so well either,’ I admitted.

Lili’s eyes widened. ‘No, no. I need you to be ok, Abi. I am so far from ok. Please tell me you’re ok.’

‘Oh, I’m fine. I’m A-Okay.’ My words came out slower than they should. Time was skipping and I was struggling to keep my feet on the floor. I stared at the small scar on Lili’s left cheek. How long had I been silent? Seconds, hours? I had to pull it together for them.

I summoned all my resources. ‘Let’s find some sugar and somewhere to sit.’ I was going to look after us, I could do this. All I needed to do was work out where we were. I took Lili’s hand and attempted a reassuring smile.

The two of us fell into the nearest supermarket. The packaging was instantly familiar. Thank God, we were back in the UK. Lili held a green and pink packet out to me: Percy Pigs. In the chilled aisle, I picked up two huge bottles of orange juice.

The cashier had a strange accent. I couldn’t understand her. Where was I? I handed her some odd-looking coins from my purse. They definitely weren’t pounds, but this didn’t seem to faze her. I gave a mumbled thanks. Walking out of Marks & Spencer and back onto the streets of Amsterdam the bubble broke; we weren’t in the UK after all. I suddenly felt very lost.

Lili clung to my hand as I led them confidently along the street. I had no idea where I was going. We just needed somewhere to sit down, anywhere. My brain was working in overdrive as I desperately tried to make out any feature of the city. We crossed a road and then a bridge over a canal. Beside me was a bench. We slumped onto it.

‘I can’t see anything.’ Lili was taking their glasses on and off, staring at the mossy bricks of the canal, partially submerged in luminous green water.

I coaxed some orange juice into them and then took a large gulp. The sugar hit me instantly, throwing the scenery back into perspective. I kept drinking. A group of tourists waved to us from a canal boat.

‘We’re never going to get back.’ Lili had stopped playing with their glasses and now clung to their red pannier bag like a lifebuoy. ‘We’ll never find our bikes again.’

‘Lili, it’s fine.’ I was beginning to sober up. ‘It’s only two o’clock, we’ve got plenty of time for it to wear off.’

Lili nodded their head.

‘Stop nodding your head.’

‘Sure, sure,’ they replied, still nodding but now slower, lolling their head back and forth. They ground to a halt. Suddenly they gripped my arm and came close to my ear.

‘I need a wee,’ they whispered. ‘I really need a wee.’

As they said it, my brain connected with an intense pressure in my bladder. We had each drunk two litres of orange juice.

‘I’ll get us to a cafe.’

I walked us steadily along a large road. I had a distinct feeling we were still heading towards the Museumkwartier. Across from us was a monumental red and white chequered brick building. On the ground floor: a cafe. We crossed the road carefully, and I ushered Lili in.

I sank into the high-backed red fabric of a booth which stretched out into infinity. A waiter approached us.

‘Do you have a toilet?’ The volume of Lili’s voice oscillated wildly with each word, ending on a booming ‘toilet’ that reverberated around the high-ceilinged cafe.

‘Yes, just down the stairs there.’

Lili slunk off the sofa and wobbled to the stairs. I smiled maniacally at the waiter who handed me a menu and walked off.

‘Your turn.’ Lili appeared beside me.

Clinging to anything I could get my hands on: the backs of chairs, the walls, the bannister on the stairs, I made my way into the basement of the building. The toilet cubicle felt safe. Its four walls enclosed me in a tiny space of my own. Maybe I could stay here forever, make it my home, hang tiny curtains along the cubicle wall.

I shook my head cartoonishly. I couldn’t let myself get distracted, I had to look after Lili. I gave myself a pep talk: Lili was relying on me, only I could get them back to the campsite safely, I had to do it for them.

Lili was sitting bolt upright in the booth, arms extended rigidly in front of them, eyes staring wildly at the menu in their hands. I slouched in next to them.

‘All ok?’ I asked quietly.

‘Uh-huh.’

It was hardly convincing.

‘Let’s order something.’ I picked up the other menu.

The waiter materialised in front of us. ‘What can I get you?’ His comforting smile made it obvious that this wasn’t the first time he’d had to deal with stupidly stoned tourists.

‘Orange juice and lemonade and tea with soy milk and a hummus sandwich, please,’ Lili spluttered. ‘And no butter in any of it, please, thank you.’

He brought over each item like an attentive nurse.

‘Thank you so, so much.’ I was intensely grateful for this kind, non-judgemental man. I chewed the food slowly. I poured sugar into my tea for the first time in years. I gradually returned to my body.

‘How are you feeling?’

‘Better.’ Lili smiled at me. ‘I think I’ll be ok.’

I looked around at the building we’d found ourselves in. Behind us was a grand hall with a high glass ceiling. The floor below me was an elaborate pattern of blue and yellow tiles. A fuchsia sign told me we were in the Cafe de Bazel, part of the city archives, the largest municipal archive in the world.

Lili cuddled into me. I pulled the laptop out of our pannier bag and we watched cartoons. The waiter brought us endless cups of tea. Slowly the colours around me dimmed. I felt the weight of Lili’s head on my shoulder and relaxed. Time was returning to normal. It felt like we’d been sitting there for hours. I looked at the clock on the wall. We had been sitting there for hours.

We left a huge tip for our waiter/hero: an apology for doing exactly what tourists shouldn’t do in Amsterdam. We emerged blinking from the building.

‘We’re such idiots.’ Lili turned to me and laughed.

‘I know, don’t …’ I felt utterly embarrassed to have made such a rookie error. ‘Seriously though, are you ok?’

Lili nodded. ‘It just felt unpleasantly like being mad, you know.’

The Van Gogh museum was a write-off; I couldn’t imagine anything worse than being surrounded by a swirling room full of post-impressionist paintings. Instead we headed back to our bikes which, despite Lili’s catastrophic predictions, were very easy to find.

I unlocked my bike and wound the chain around the stem of my saddle. Today had been a disaster. Nothing we had done since leaving the UK had convinced me that we could do this cycle tour. In a few days’ time we would be leaving the safety of the campsite at Durgerdam. I just hoped we would be ready.

Day Seven, Durgerdam to Fort Spion

‘Why the FUCK did I bring this FUCKING UKULELE?’

I hurled my rucksack to the ground and stared at it resentfully. This was not how I’d imagined our great departure from Durgerdam. We’d woken up a full hour later than I’d planned. As I’d frantically stuffed clothes into dry bags, Abi had stood bemused. She clearly didn’t understand the importance of sticking to our invisible schedule. I hadn’t had time to bungee my bag to the back of my bike, or shower, or cook breakfast. I wasn’t ready to leave.

I can’t do this.

The dam broke and I collapsed into tears. Abi slid off her saddle and, bike still between her legs, shuffled over to me. She put her hand on mine as I exhaled all the tension, anxiety, panic and fear in several loud and messy sobs.

‘Ok?’ Abi asked.

I looked up at her. She smiled reassuringly.

I nodded, mopping up the tears and snot with the back of my hand.

‘Shall we attach this to the back of your bike?’ She picked my rucksack off the verge. I’d spent the whole morning refusing her help and snapping at her, trying to regain control over the situation and my spiralling anxiety.

‘Thanks. Sorry.’

With it secured onto the top of my rear pannier rack by bungees, we wobbled off along the cycle path.

The two of us were travelling south into the body of the Netherlands. Turning off the lakeside path, we followed the numbered cycle paths, veering right and joining a canal, the water dappled with sunlight. With our route stretching out ahead of us, I began to relax. Even with the weight of the bags, I was comfortable with this sort of cycling. The Fens, which border my home town, share a resemblance with the Netherlands: large agricultural areas, created by draining marsh and wetlands, characterised by dykes, ditches and pumping stations. I grew up riding bikes on unending, straight roads beneath a broad, open sky.

Riding like this breeds its own kind of stamina. I focused my attention on the movement of the pedals, the metal hum of the chain, the idiosyncratic clicks of my bike: the rhythm of riding.

The trees that lined the towpath cast bars of shadow, making the light flicker as we rode. The canal path ended, and we followed the cycle path as it turned onto a road.

Two hundred metres down, we stopped at a roundabout. It wasn’t clear which of the three turnings to take. There were no cars, so I took an exploratory pass. At the exit towards Utrecht a bright flash caught my eye: sunlight reflecting water. I knew we were meant to be following a second canal. I didn’t want to stop and check a map, keen to cling onto this feeling of momentum. I pointed the way.

We came out onto the broad waterway, double the width of the first. Long industrial barges sheared through the water. The towpath was lined by trees, but with the sun now overhead they offered no respite. Abi was the less experienced cyclist, so I let her set the pace, and on the wider sections of path I pulled up alongside her. For the last year, on every bike ride we’d taken together, I had come up beside her and said, ‘Imagine: this, but we’re cycling across Europe.’ These rides were normally our commute to and from work. It felt strange to have transplanted this familiar activity somewhere completely new. The same action, the same motion, the same push of the pedals was transformed from something everyday to something significant.

‘Can we stop and eat something?’ Abi’s voice broke my reverie.

It was nearly midday and in my panic this morning I’d vetoed breakfast. We’d planned a short ride for our first day, 25km. I didn’t think we’d be going for much longer.

‘Sure.’

We pulled off the path to a bench that sat looking out over the water and across to the fields dotted with windmills beyond. I pulled a flapjack from my bar bag and broke it in half.

‘Not much further now,’ I handed Abi her half, ‘this’ll keep you going.’

‘Is this right? This doesn’t feel right.’

An hour had passed, and we were still on the canal towpath. It felt like we were cycling the same 100 metres over and over again. The idyllic path of earlier had become a Sisyphean nightmare.

‘Let’s keep going a little bit further.’ I just wanted to keep pedalling.

‘We can’t just keep pedalling and ignore that we are lost,’ Abi called out from behind me.

I didn’t reply; I’d spotted a woman walking towards us, carrying her shopping. She was the first person we’d seen in hours.

‘Excuse me?’

She looked up, surprised.

‘Waar … waar …’ I started. In lieu of Dutch, I pointed at our map.

‘U bent van harte verloren?’

I looked at Abi who reflected my expression of total incomprehension.

‘Waar …?’ I continued.

The Dutch woman began to talk in an animated way, pointing to a place on the map far south of where we were. I pointed to our intended destination and gestured back and forth down the canal. She pointed back the way we had come. Even without understanding what she was saying, her answer was clear: we were lost.

Abi and I discussed our options as the Dutch woman continued away from us along the towpath.

‘We need to figure out where we are,’ I began.

‘Right.’ Abi nodded agreement.

‘Then we can figure out how to get back on track.’

‘The bike route signs don’t make any sense, there’s no indication of what towns or villages we are near, and this towpath appears to just continue indefinitely …’

‘So, we need to get off the canal,’ I concluded.

We cycled back, towards a junction. The path split and we travelled under a small bridge and onto a road. Agriculture shifted into residential streets, and we were soon cycling through a small village. At a public park I spotted what we were looking for: a wooden board with a map of the area.

‘Ok, ok,’ I muttered, scanning the board and trying to relate it to the map Abi had open in her hands, ‘Mijnden … Nieuwersluis … Breukelen … Oh.’

The canal I had confidently pointed to headed south rather than west. We were nowhere near our intended destination.

I looked over at Abi, trying to read her reaction.

‘Why didn’t you let me stop and check?’ she said. ‘You know you can’t read maps; you know I have a better sense of direction.’

She paused.

‘I can’t keep cycling,’ she croaked out before her face collapsed.

If I could have gone home then and there, I would have. The whole tour seemed a terrible mistake. We didn’t know what we were doing.

I shook my head. I needed to focus on the immediate problem. Whatever we did, it was going to get dark and we needed somewhere to sleep.

‘Can I have another look at the map?’ I asked Abi. She passed it over without saying anything or looking at me.

‘Ok, we’re here,’ I pointed to the small village, ‘and there’s two campsites next to each other, here and here.’

I pointed to a road about 10km away. I looked over at Abi, whose eyes were watching my fingers.

She squared her shoulders. ‘I’m going to figure out the route.’

She pulled out the Michelin road map from the dry bag on her front pannier rack and silently began comparing it to the map of the bike routes.

‘It probably didn’t help that this isn’t the most topographically accurate map,’ she said gently, holding out the bike routes map and offering forgiveness.

The journey to the campsite wasn’t more than a thumb’s width on the map, but it felt never-ending. We took turns asking the other to stop so we could anxiously check the map. We rode back north through the town of Breukelen along cycle paths, paved in red-brick, that wove past low suburban houses and manicured lawns. In the small village of Mijnden we cycled through narrow streets lined with white brick houses. I stopped at the end of a line of traffic in front of a drawbridge, raised to allow a procession of Dutch holidaymakers cruising in pleasure boats to pass through.

We almost missed the low wooden gate to Fort Spion. It was obscured by overhanging trees and tall grass. Wheeling our bikes back round, we pushed them up the gravel path. We were standing in the shadow of a large grey stone fort.

‘Hallo!’ A woman striding down the path called out a greeting.

‘Er … Kamperen?’ I ventured.

‘Camping, yes?’

‘Yes, please.’ Were we so obviously English?

‘How long?’

‘One night.’ I paused and looked at Abi. ‘Two nights.’

‘Of course.’ She unlocked the door to a small wooden shed, hidden behind dense bushes, and disappeared inside. We stood outside with our bikes, waiting.

‘Are you members?’ she shouted out to us.

‘Members?’ I asked.

She popped her head out the door. ‘Fort Spion is a Natural Camping site.’ She handed me a small green book. ‘To stay you have to be a member, it’s 15 euros but it lasts a year and you can stay in any of them.’

I rested my bike against my leg and flicked through the book. The natural campsites or Natuurkampeerterreinen were a scheme of about 150 campsites across the Netherlands. They all catered exclusively for tents, and were designed and managed in a way that was environmentally conscious, and sympathetic to the landscapes they were in.

‘I don’t think I have enough cash to pay for membership.’ I handed Abi the book and scrabbled around in my bumbag.

The woman waved her hand at me. ‘You can pay tomorrow.’ She looked us up and down. ‘You look like you need some rest.’

Day Eight, Fort Spion

I woke up early to the sun filtering into the tent. I’d slept deeply. Yesterday’s exertion had knocked me out as soon as my head touched the dry bag I used as a pillow. Stretching my arms, I unzipped the inner tent, then, turning onto my stomach and shuffling forward to extend my reach further, unzipped the door of the outer tent.

Bright morning light shone in, and Lili began to stir. I lay still on my mat. The doorway acted as a frame for the view outside. The lake glimmered softly, and a warm haze hung in the air. We were beneath the green boughs of an elm tree. This was what I wanted from the tour.

I breathed in the fresh air. I knew being outside was good for me in a way I couldn’t pin down. I had escaped the claustrophobic city. I had escaped our tiny bungalow which we couldn’t afford the rent on. I’d escaped from the pressures of the everyday and the worries about what I was doing with my life. I felt an overwhelming sense of calm. I was no longer going to be the Abi who ate family-sized bags of Doritos while binge watching season after season of Peep Show. Yesterday had been hard, but I had proved that I could do it. I felt excited about the day and all its possibilities.

I stood up and immediately sat back down. ‘Oh my God!’

‘What’s the matter?’ Lili asked sleepily.

‘Everything,’ I mumbled back, rubbing my right calf. ‘Everything hurts.’

I allowed my brain to connect with my broken body. My legs were made of lead, I was sure of it. The heavy ache was worse in my thighs but spread all the way to the soles of my feet. Moving my joints sent out agonising shockwaves. Pain radiated from my shoulders down to my wrists. My neck hurt, my back hurt, even my fingers and toes hurt.

‘JESUS!’ I had just adjusted my pyjama bottoms. I was raw with saddle sore.

It didn’t sound like Lili was faring any better as they began to move from their sleeping bag.

‘What have we done?’ they asked through gritted teeth as they rolled onto their hip and then instantly back again. ‘I don’t think I can get up.’

I looked at Lili rocking violently from side to side in an attempt to sit up and then at my poor body sprawled on the mat. I couldn’t help but laugh.

I was glad we were taking a rest day.

‘Here you go.’ Lili handed me a pot of oaty mush and apple.

I hate porridge, but I was willing to try and eat it during the tour as it was cheap and light to carry. As I took my first bite, I suddenly realised I’d neglected another part of my body: my stomach. I was ravenous. I shovelled the gelatinous paste into my mouth and then grabbed seconds. Lili did the same.

‘I really don’t think one flapjack is enough for anyone for lunch.’ I side-eyed Lili. I wasn’t going to forget their enforced and unrelenting march yesterday in a hurry.

‘I know.’ They looked up at me guiltily. ‘Sorry.’

‘It’s ok.’ I pulled a packet of emergency noodles out of our food bag. ‘Second breakfast?’

Lili shook their head and, with stunted movements, prepared a bag for our trip into town. I inhaled my noodles and tried to mentally prepare for the short ride in. I was desperately tired, and the calm of the campsite was hard to resist, but we had jobs to do.

‘Ready?’ Lili stood over me expectantly.

‘I guess so. I’ll just pop to the loo first.’ I pulled myself off the grass. My body creaked.

An ancient wooden door led to a single toilet surrounded by cobwebs and their eight-legged residents. I sidled in. Sitting down, I let out an involuntary whimper. Weeing was agonising. I waddled back to Lili and my bike.

‘I think I’m going to ride standing up,’ I proclaimed. I doubted I’d ever be able to sit down again.

Large, white mansions and tall willow trees lined the quiet road as we cycled towards Breukelen. My legs were sore, but I was determined to enjoy the ride. We crossed a canal filled with boats of all shapes and sizes navigating the water, weaving in and out of one another; Dutch tourists on their holidays. The water’s edge thronged with people eating breakfast in the sun. On my bike, I felt part of the scene, another holidaymaker enjoying the beautiful day.

I paced the aisles of the supermarket. Lili held up two options.

‘What would you prefer, a kilogram of table salt or a small grinder of pink Himalayan salt?’

I sighed. ‘I guess the grinder makes more sense?’

‘Great.’ Lili placed the kilogram bag down. ‘I guess we’re now officially the most middle-class cycle tourers in the world.’

I laughed and then grimaced. There were hundreds of reasons I didn’t feel like a proper cycle tourer and this was just another one. The salt screamed luxury; it screamed glamping. Real cycle tourers probably didn’t need salt. They probably ate only mouldy bread and food gleaned from farmers’ fields.

Every time I got on my bike, I felt like I was being sized up. At 18 stone, I didn’t look like a cyclist. I didn’t feel like one either.

It hadn’t always been this way. As a teenager I’d loved cycling on my simple mountain bike. Its purple frame had been a perfect fit, every turn of the pedal a natural extension of my legs. I’d ridden it as quickly as I could around the neighbourhood, watching the numbers tick higher on the speedometer my parents had installed.

It didn’t take much to break my love affair with my bike. A throwaway comment by an older boy who looked at the large, comfortable gel saddle cover I used and remarked, ‘Guess you need that for your fat arse.’ I immediately removed the cover.

I stopped cycling. My oversized body had become an object which people felt compelled to discuss, to criticise. I couldn’t verbalise the shame I felt, but I knew that if I stopped cycling, stopped exhibiting my body in motion, I might become invisible again.

When I got back on my bike as an adult for my commute to work, it was hard not to feel that same shame. I felt exposed. I knew that the surprise which registered on people’s faces when we told them about the cycle tour had nothing to do with Lili. They were looking at my fat body and deciding what it was capable of.

We wandered out of the supermarket into the sunlight and sat on a bench in the small town square. The shops around us were mostly closed or were bargain shops, a stark contrast to the gentrified streets along the canal.

‘How are you feeling?’ I asked Lili.

‘Tired, dazed. You?’

‘Tired.’

It was not yet midday but yesterday had completely exhausted us.

‘Let’s go back to the campsite.’

The afternoon at Fort Spion passed quietly. My feelings about the tour oscillated between excitement and anxiety. Travelling was all I had thought about since leaving university three years ago, but I’d never found a way to do it which was affordable, or which fitted with my values. When Lili first mentioned cycle touring, on our first or second date, it made perfect sense. I wouldn’t be pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere just so I could take a few nice Instagram pictures and enjoy the sun. I wasn’t going to be just jumping into another culture, spending money in the tourist areas and then jumping back out again. I’d have the opportunity to experience each tiny place, to see much more of a country than was possible by train or plane. All it would take on my part is getting on my bike.

I settled next to Lili on a bench overlooking the lake. So much of my life was spent inside; working, eating, sleeping, and now I was planning to live predominantly outside for the next year. It felt like a necessary change. My head was beginning to feel clearer.

I watched the sparrows flitting between the bushes beside the lake. A Red Admiral butterfly floated onto the arm of the bench. A large black fly swooped down onto my leg.

‘OUCH!’ I yelled.

Lili jumped in alarm. ‘What?’

I pointed to the fly on my leg. ‘It’s biting me! What the fuck is it?’

Lili looked in horror at my leg. ‘Well, wipe it off!’

The fly continued to devour me.

‘Can I do that? Are you sure?’

‘YES!’

I prepared myself for the fight of my life. Lifting my hand, I softly brushed it off. The sated fly buzzed away happily.

‘What the hell was that?’ I asked Lili, wide-eyed in panic. ‘It just wouldn’t stop biting!’ The bite was bleeding and radiating pain up my leg. ‘And it really hurts!’

‘I have no idea.’ Lili had jumped up and was scanning the sky.

I looked over at the tent. ‘Maybe we should head inside.’

Day Nine, Fort Spion to Paalkampeerterreinen

‘Jesus Christ.’ I was trying to lower myself onto the saddle. ‘Do you think we’ll ever adjust?’

Lili was a much more experienced cyclist and my only reliable reference for what lay ahead.

‘We should do.’ They let out a moan as they sat down.

We set off along a road which floated between two wide lakes. The flatness of the landscape left me feeling like we were cycling across the water. Midges hung in dark clouds along the side of the road, and occasionally Lili or I would swerve wildly to avoid them but would usually end up with a face full of bugs.

Our destination was our first wild camping spot, nestled in Hoge Veluwe National Park. ‘Wild Camping’ is any camping outside of designated campsites, and it’s illegal in most European countries. However, the Netherlands offered a system of Pole Camping sites or Paalkampeerterreinen: areas in forests and woodlands where people could legally wild camp, marked by a wooden pole which the campers must stay near.

We needed our money to stretch as far as possible, so wild camping was an inevitable part of the tour. I found the idea terrifying. As we cycled along the quiet lanes, I worried about all the risks we were taking. There would be no gates or fences to protect us tonight. The tent was just a flimsy piece of fabric. We would be completely vulnerable.

I’d read a lot about people’s experiences of wild camping and the joy and excitement they felt. None of the cycle tourers we followed on Instagram seemed as scared as I was. I didn’t know if I would be able to push down my fear to enjoy the experience. I wasn’t even sure which fears were worth taking notice of and which were over exaggerated by a society fixated on the harm strangers could do to you.

The long road ended, and we rolled onto a white sandy path surrounded by dry open heath. The path dipped and dived like a pump track. My legs, which had had time to loosen on the flat roads, started to seize again, my muscles screaming out at every uphill.

‘I thought the Netherlands was supposed to be flat?’ I shouted ahead to Lili as we laboured up a steep incline. My breathing was coming in ragged gasps. What had made me think I could do this?

‘I’m sure it’ll even out,’ Lili shouted back. They continued cycling forward, lost in a race that only they were competing in.

The morning cool had given way to a fierce heat. I could feel beads of sweat dripping down my back as the temperature crept into the thirties. We darted in and out of woodlands of looming pine and gnarled birch, their shade a welcome relief on a hot day.

‘I need to stop for water!’ I looked at my watch. We’d been cycling constantly for three hours.

Lili let out a huge bodily sigh and cycled back to me. I took a large glug of warm water from my bottle. Salt from my sweat had crusted onto my face, I could taste it in the corners of my mouth.

‘Ready?’ they asked, keen to get going.