Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peepal Tree Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

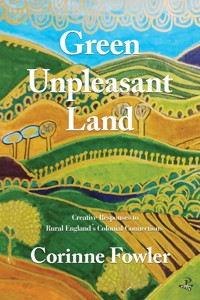

Selected by Bernardine Evaristo as an Observer Best Books 2021 Green Unpleasant Land explores the repressed history of rural England's links to transatlantic enslavement and the East India Company. Combining essays, poems and stories, it details the colonial links of country houses, moorlands, woodlands, village pubs and graveyards. It also explores the links between rural poverty, particularly enclosure, and colonial figures, such as plantation-owners and East India Company nabobs. Fowler, who herself comes from a family of slave-owners, argues that Britain's cultural and economic legacy is not simply expressed by chinoiserie, statues, monuments, galleries, warehouses and stately homes. This is a shared history: Britons' ancestors either profited from empire or were impoverished by it. Green Unpleasant Land argues that, in response to recent advances in British imperial history, contemporary authors have reshaped the pastoral writing to break the powerful association between the countryside and Englishness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 689

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GREEN UNPLEASANT LAND:CREATIVE RESPONSES TO RURAL BRITAIN’SCOLONIAL CONNECTIONS

CORINNE FOWLER

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

Part OneEMPIRE, LITERATURE AND RURAL ENGLAND

Chapter 1: Nation at the Crossroads

Chapter 2: Green Unpleasant Land

Chapter 3: Pastoral

Chapter 4: Country Houses

Chapter 5: Moorlands

Chapter 6: Plants, Gardens and Empire

Part TwoCREATIVE RESPONSES: THE COLONIAL COUNTRYSIDE

Fields Strawberries

Gardens Azaleas

Graveyards Myrtilla

Hills Cotswolds

Maypoles Green and Pleasant Land

Moorlands Heathcliff

Parks Kings Heath Park

Pastoral A New Chronology

Pubs Public Houses of Britain

Seeds William Blathwayt of Dyrham Park

Woodlands An Escaped Slave from Yorkshire, 1789

Epilogue

Further Reading

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Books are always a collective effort. First of all I want to thank Jeremy Poynting, the founder and managing editor of Peepal Tree Press. Thanks to Jeremy’s efforts, I have been able to incorporate considerably more historical and literary material than I would otherwise have done. He also urged me to think more deeply about the importance of class to the analysis. In particular, his editorial interventions allowed me to connect, and evidence, rural poverty at home with colonial activity abroad. The existence of Peepal Tree clearly demonstrates the importance of quality independent presses. I also want to thank Jacob Ross, the associate editor, for his judicious and forensic editorial input to the creative material and to Hannah Bannister for keeping everything on track no matter what.

This book represents one of many efforts to provide a sound basis of evidence as a resource to inform public discussions about British colonial history. Once again, this is a collective effort. I wish to thank a list of exceptional people for the insights that they have contributed through their work and for the Colonial Countryside project: Robert Beckford, Caroline Bressey, James Dawkins, Misha Ewen, Radikha Holstrom, Rozina Misrah, Sumita Mukherjee, Shawn Sobers, Florian Stadtler, Anthony Tibbles and Kristy Warren. My close colleagues have given sound advice and offered timely support: Rabah Aissaoui, Gowan Dawson, Lucy Evans, Zalfa Feghali, Clive Fraser, Martin Halliwell, Sarah Knight, Mary Ann Lund, Suzanne MacLeod, Richard Thomas, Richard Sandell, Philip J. Shaw and Victoria Stewart. In the heritage sector itself are many talented and brave colleagues whom I admire: Dominique Bouchard, Rhian Cahill, Laura Carderera, Matthew Constantine, Alison Dalby, Emile de Brujin, Liz Green, Andrew Hann, Emma Hawthorne, Charlotte Holmes, Tom Freshwater, Indy Hunjan, Nadia Hussain, Sally-Anne Huxtable, John Orna-Ornstein, Polly Schomberg and Nino Strachey.

There is another group of people to thank who have provided moral support and applied their fine minds to this book’s topics, making me see things anew. They are Clare Anderson, Kavita Bhanot, Joanna de Groot, Katie Donington, Madge Dresser, Elisabeth Grass, Marian Gwyn, Sarah Longair, David Olusoga, Raj Pal and Laurence Westgaph. I particularly want to thank the amazing Miranda Kaufmann, the generous and clearsighted lead historian of Colonial Countryside. For giving me moral support and courage, I want to thank Hamida Ara, Desiree Baptiste, Jane Baron, Steve Baron, Yannick Guerry, Halgurt Habeel, Peter Kalu, Carol Leeming, Hari Matharu, Edy Motta, Henderson Mullin, Kevin Ncube, Yewande Okulele, Raj Pal, Lynne Pearce, Harry Whitehead and Binnie Sabharwal. Finally, to my long-suffering parents, Malcolm and Yvonne Fowler and my twin sister Naomi Fowler.

PREFACE

A hand shot up. My questioner looked quizzical. I pointed at him and he said, ‘Doesn’t this sort of approach undermine your position as a literary critic? Writing a book with poems and short stories in it?’

I expected the question, but it’s taken me a while to formulate an answer. For this academic, I had crossed a line. To him, creative writing is expressive, not analytical. He felt that this book would be fatally compromised because I saw my stories and poems as integral to its commentary. I was supposed to write about writers, not with them. His tone was confident, his question a statement. I was reminded of the writer, Graham Mort, who once remarked that university literature specialists view creative writing as ‘an interesting cultural secretion’. Having betrayed my own propensity to secrete poems and stories, my impartiality was now in question.

I should have replied that writing both critically and creatively has respectable antecedents. The Welsh novelist and critic Raymond Williams observed that research topics are invariably linked to personal stories. See the topic and you see the person. Williams did not consider this a bad thing. Most academics accept that impartiality is an illusion. When personal motivations animate scholarship, it is a bad idea for these to remain unconscious, unexamined and undeclared because they cause intellectual distortion. I take comfort in the fact that Williams wrote Border Country (1962), an account of his childhood and youth as well as The Country and the City (1973).1 We at least share the same theme, and – more than this – Williams’s work shaped that of Edward Said, author of Orientalism2 and a parent of postcolonial studies, my own area of study.

Here is my story. I became obsessed with country houses’ colonial connections whilst writing an article about them. I pre-ordered every forthcoming book. I kept Slavery and the British Country House (2013)3 and Country Houses and the British Empire, 1700-19304 beside my bed. One night I dreamt about Charlecote Park. In another dream I walked a grassy track leading from Penrhyn Castle to Erdigg, where I later saw a portrait of a Black coach-boy. I started staying up long after midnight writing poems and stories. Realising that reading and writing about country houses had become strangely compulsive, I decided to contact my cousin Yannick, who dabbles in family history, to ask if he knew of any blood connections to empire or to country houses. Yes, he replied, the French side of our family – the De Caradeucs – profited from Caribbean sugar wealth. One branch of the family lived at the Château de Caradeuc at Bécherel in Brittany, which they built with sugar money. This branch did business with another family member who owned plantations in St. Domingue (Haiti). Jean-Baptiste De Caradeuc was Governor General of San Domingo. At the onset of the Haitian Revolution, he fled the island with 62 enslaved people – including a wet nurse known by the family as ‘mama monkey’.5 He was known to be cruel. He is almost certainly the character Citoyen C in Victor Hugo’s short novel Bug Jargal (1826),6 about the revolution. De Caradeuc impaled babies on sticks outside his plantation at Croix-des-Bouquets.7 He received compensation from the French government for the loss of the people that he had enslaved, and he used the money to develop plantations in South Carolina. His mixed-race descendent, Carole Ione, wrote a book about her experiences called Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color.8

The colonial connection did not stop there, my cousin told me. Another branch of my family were the Poidloüe, naval people who captained East India Company ships. My relatives sailed from Lorient, leaving docks from which 150 slave-trading ships also departed. My family had both East and West Indies links. Only then did I understand in the fullest, most personal sense, why I was compelled to write this book, which unites historical work on the Caribbean and the East India Company as though joining two halves of my family history. And only then did it occur to me – since I arrived at this understanding through a creative process rather than an academic one – that creative instincts possess an intelligence of their own.

I make no claim to neutrality. Even if Jean Baptiste de Caradeuc is not the Citoyen C of Hugo’s novel, my own family history reveals an aspect of imperial Britain’s repressed story. Britain’s colonial legacy is not simply expressed by chinoiserie, statues, monuments, galleries, warehouses and stately homes. For Britons with roots in all continents, people’s ancestral stories stray far beyond British shores. Our relatives either profited from empire, or were impoverished by it. This history lives on. An eerie parallel to my own story is that of Ripton Lindsay, a British resident. Ripton Lindsay is the three times great grandson of an enslaved woman named Susanna, and Alexander Lindsay (1794-1801), the Scottish Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica and an owner of plantations worked by enslaved Africans. Having investigated his family history for years, Ripton Lindsay arranged a meeting with Alexander Lindsay’s descendants, who live in Britain today. In his account of this encounter he writes: ‘I would like to… create a greater understanding of how Alexander became the man he was and why I believe that the recognition of this is important in the reconciliation of the past and, along with creating a wider understanding of the harsh impact of slavery’s legacy, I believe that in sharing these stories we can help forge a better future for us all.’9

My parents gave me a love of country walking. We went on long walks every Sunday in all four seasons. I had no idea, then, that rural England had any relationship to the British Empire, of which I had learned little at school. As a child I experienced those woods, villages and valleys as quintessentially English. I was then wholly ignorant of my family connection to transatlantic slavery and the East India Company. I did not see that the countryside could express colonial wealth. I did not associate the landscape with people of African or Asian descent. I had no idea that my untroubled relationship with nature was not universal. Nor did I see the historical connection between slave-ownership and enclosure’s hedgerows, or colonial wealth and rural philanthropy. Green Unpleasant Land, therefore, begins at home and extends outwards to empire but circles back to the English countryside. The book is purposely reparative. It respects the ghosts of people encountered on my journey towards understanding that “England’s green and pleasant land”,10 to quote William Blake, is not just about agriculture and estates, but about colonialism and a long-standing Black presence. The book includes creative work because I have indeed crossed a line. I embrace the academic principles of originality, significance and rigour, but it is time to declare an interest. This book lays aside any pretence that I am not involved. I am involved, and this story belongs to all of us.

I have organised this book to tell several parallel stories. The first two chapters provide overviews of the relevant work done by others so far, and the following four offer more detailed discussions of the specifics of landscape and the countryside, country houses, moorlands, plants and gardens, in which I include allotments and public parks.

Chapter One focuses on the responses to two attempts to tell different kinds of national stories: Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympic Games and the National Trust’s publication of a report on the colonial connections of properties they manage. The chapter presents a rationale for bringing together histories of empire, the place of rural Britain in that history and the presence of Black and Asian Britons as both experiencers of, and writers about, the countryside. I acknowledge the existing research this book attempts to build on and argue that the determined opposition to an anti-colonial history suggests a nation at the crossroads: either prone to comforting nationalist myths, or a country ready to embrace its fuller histories and the global connections of its people.

Chapter Two explores the changing features of rural Britain in historical and contemporary reality, the shifts in attitudes towards the countryside in social commentary and literary portrayal, and it introduces the book’s focus on writing by Black and Asian Britons about that aspect of Englishness which seems most exclusionary.

Chapter Three situates English rural writing in a global setting, a recontextualisation that reveals the limitations of concepts such as pastoral, georgic, anti-pastoral and even postcolonial pastoral. In the context of rural writing’s colonial dimensions, I then acknowledge the scope and significance of contemporary rural writing by Black and Asian Britons whose work draws on both rural literary tradition and personal experience to join, reanimate and deepen England’s longstanding literary conversation about the colonial countryside. This book investigates changes in literary writing about the rural landscape and rural activities. The chapter examines how established poetic traditions of the pastoral and the georgic defined most writing about the countryside until at least the 18th century and suggests that as generalising and abstracted forms, these still enter our views at a mythic level. The chapter examines how this body of work, from the 17th to the 20th century, has engaged with, or can be read against, the impact of colonial activities on the economy, society and culture. I track a shift from the pastoral and the georgic and consider the challenge to these generally elite views of the landscape from plebeian and women’s perspectives. Here, in particular, I look at the writing that responded to enclosure and the loss of commoners’ rights. The chapter examines other challenges to views of the countryside that derives from classic Greek and Latin literature from that revolution in sensibility – equally part of our contemporary consciousness – that we identify by the label of romanticism. Another focus concerns views of the rural that deal with the individual, cultural and psychological roots of perception and the particularity of place. I look at these traditions within the context of empire and show how Black and British Asian writers have engaged with English traditions of rural writing, sometimes in dialogue with it, sometimes quarrelling with it, sometimes ignoring it altogether.

In Chapter Four I consider the country house, its associated literature and the way the genre of the country house poem provided a screen for the reality of how many such houses were involved with both the West and East Indies. I look for traces in fiction and poetry of how writers responded to imperial histories, in particular through the genre of the gothic. I also look at the rare attempts to see the country house world from below. I see Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park and the debate about her work stimulated by Edward Said as central to the kind of national ‘culture wars’ discussed in Chapter One. From here I explore how Black writers are re-imagining the country house’s connections to the hidden world of the Caribbean plantation and those actual Black presences in Britain, including domestic servants, mostly young enslaved children, who can be seen in hundreds of country house portraits of the 17th, 18th and early 19th centuries.

Chapter Five looks at moorlands, so very opposite from the artfully tended grounds of country house estates. In the context of examining changing ideas about the cultivated and the wild, the picturesque and the sublime, the civilised and the savage, I focus on Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847). I consider the novel’s location in the economy of empire and the aftermath of emancipation in the West Indies. The chapter investigates the debate about Heathcliff’s ethnic identity and discusses contemporary filmic and literary responses to Emily Brontë’s novel, including Andrea Arnold’s eponymous film and the intertextual novels of V.S. Naipaul, Caryl Phillips and Maryse Condé. I also record efforts by groups of Black walkers to take their own possession of the moors both through walking and through making a play about the experience.

Chapter Six focuses on and explores the cultural history of gardens as shaped by empire and migration. I review how researching gardens reveals the colonial-era transportation of new edible and ornamental plants to Britain and the notable examples of slave-gotten wealth that funded the late 18th and early 19th-century passion for botany and plant collecting. The chapter looks at the role of institutions such as Kew Gardens in imperial commerce and its activities that made possible the expansion of empire into Africa. But I also look at how a love of plants spread beyond the elites, as reflected in the poetry of John Clare, in particular. The chapter also tells a counter story: how enslaved Africans changed the foodways of the Americas by bringing grains and vegetables with them on the slave ships, foods that enabled them to survive, maintain their culture and establish the distinctive creole cuisine of the Caribbean that is now also part of British culinary culture. The chapter also looks at those aspects of the vernacular garden – allotments, public parks and the suburban garden – that engaged the majority of the population. The chapter sees poetry about gardens as one of the most floriferous zones of writing by Black and Asian Britons.

The second half of the book contains my own response to this topic in fiction and poetry that explores the colonial aspects of other rural phenomena: country estates, fields, flowers, graveyards, hills, parks, village pubs and woodlands. If rural England’s relationship to empire was once selfevident, later generations have largely forgotten it. These creative pieces are written in the recognition that no academic study can do justice to the human stories which are routinely lost in historical writing.

The terms Black British and British Asian are used throughout the book in preference to BAME or other formulations. As socially constructed categories, the terms Black British and British Asian do, of course, risk conflating peoples of diverse origin, class and identifications into ludicrous single categories. Nonetheless, use of the term Black, particularly, gestures towards earlier positive constructions of Black identity. Wherever possible, the book is precise about the cultural heritage of the people it discusses.

Endnotes

1.Raymond Williams, Border Country (London: Chatto & Windus, 1960) and The Country and the City, (London: Chatto & Windus, 1973).

2.Edward W. Said, Orientalism, (New York: Pantheon, 1978).

3.Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann (eds.), Slavery and the British Country House (London: English Heritage, 2008).

4.Stephanie Barczewski, Country Houses and the British Empire, 1700-1930, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016,).

5.Musée de Lorient, ‘Traite et Esclavage’, https://musee.lorient.bzh/collections/traite-et-esclavage/, accessed 9th November, 2020. Thanks to Yannick Guerry, independent researcher, for providing this information.

6.Victor Hugo, Bug Jargal (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1826).

7.David P. Geggus (ed.), The Impact of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001), p. 232.

8.Carole Ione, Pride of Family: Four Generations of American Women of Color, (South Carolina: iUniverse, 2001).

9.Ripton Lindsay, ‘Alexander Lindsay and Jamaica’, file:///C:/Users/csf11/ AppData/Local/Microsoft/Windows/INetCache/Content. Outlook/ 6EWB7WB2/Alexander%20Lindsay%20and%20Jamaica %20(2019%20Edition).pdf, p .27. Accessed 28th September, 2020.

10.William Blake, Preface to Milton, a Poem, Edited by Robert N. Essick and Joseph Viscomi ([1810] Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

PART ONE

EMPIRE, LITERATURE AND RURAL ENGLAND

CHAPTER ONENATION AT THE CROSSROADS

‘Thank God the athletes have arrived! Now we can move on from leftie multi-cultural crap. Bring back Red Arrows, Shakespeare and the Stones!’ (Tweet by MP Aiden Burley, Olympics Opening ceremony, July 2012).

It was Friday night on 27 July, 2012. The London sky was overcast and a BBC commentator worried aloud about the prospect of rain. There was tension in the air: Britain was about to be showcased to a worldwide television audience of over 900 million people. As the countdown began to the official opening of the Olympics Ceremony, viewers were reminded that ‘Isles of Wonder’ was choreographed by Danny Boyle, the celebrated director of Trainspotting (1996) and Slumdog Millionaire (2008).1 The choice of Boyle as creative director had been announced two years previously. Back then, news media coverage of the impending spectacle was cautiously optimistic. The Guardian went so far as to express ‘delighted astonishment’ at the choice of Boyle.2 But none of this could quite dispel the air of trepidation: would London’s opening ceremony rival Beijing’s 2008 offering? ‘Isles of Wonder’ came with a high price-tag. At £27M it had consumed twice its original budget, yet at £65M the Chinese had spent considerably more.

As nine o’clock loomed, the BBC’s aerial cameras zoomed in on the Olympic Stadium’s blazing lights. As Big Ben’s amplified chime faded, ‘Isles of Wonder’ began with Journey Along the Thames, a two-minute BBC film directed by Boyle. As the film’s title and length imply, the River Thames is followed at high speed from its source in a Gloucestershire field to the heart of London. This journey is full of references to rural representation, from the English idyll to more radical depictions of the countryside by film-makers that Boyle admired, such as Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger whose film, A Canterbury Tale (1944), depicted rural Britain as a place of labour and a place of change (landgirls in the fields), but also a place resistant to change. In its opening frames, Journey Along the Thames follows an improbably blue dragonfly as it flits along the water’s surface. Insofar as the dragonfly evokes hot, bygone summers, it belongs to the symbolic terrain of England’s pastoral idyll. Yet its ultramodern electricblue colouring gives an early indication that the film is concerned with updating established ideas about rural England. The film itself is speededup, a device which indicates the passing of time as though to indicate progress from traditional mind-sets. Below, I examine two scenes from the opening ceremony to understand why some spectators were so provoked by it. Their anger is symptomatic of widespread lack of awareness that England’s coastlines, country houses, moorlands, villages and woodlands have multiple global and colonial connections, which this book explores.

Successive images in Journey along the Thames unfold to the accompaniment of ‘Surf Solar’, by a two-piece, mixed-race pop band called Fuck Buttons. Their soundtrack underlines the film’s concern with diversifying images of rural Britain. Boyle’s letter in the ceremony’s official guide hints at this agenda:

‘This is for everyone’ is the theme of the opening ceremony… We can build Jerusalem. And it will be for everyone.3

The concept ‘for everyone’ was soon afterwards adopted by the National Trust in its efforts to make the organisation more inclusive. The reference to ‘Jerusalem’ – the song which is commonly considered England’s ‘true national anthem’, based on a poem by William Blake – calls for the creation of a better world, built on ‘England’s green and pleasant land’, a land which – in the context of the opening ceremony – belongs to all, regardless of ethnicity. Yet, as studies of rural racism have consistently shown, rural England is a fiercely guarded site of belonging.4

Early on, Journey to the Thames presents its viewers with two white boys playing in the river with nets and jam-jars. The boys are immersed in a soundscape of birdsong, sloshing water and echoing laughter. It probably refers to a scene in A Canterbury Tale where boys are playing by a river. Two elements of this scene suggest its historical provenance: the receding echoes of laughter and the once-popular pastime of collecting specimens. Its fleeting image is calculated to evoke nostalgia for a lost era of unsupervised play in English meadows. The notion of the rural idyll is evoked by Kenneth Grahame’s riverside classic The Wind in the Willows (1908) when Ratty, Mole and Toad flash on to the screen. The camera passes under a Cotswold bridge before returning to the theme of childhood exploration with a medium close-up of a child brushing his palm against ears of corn. This last image is also given a historical flavour, viewed through a keyhole as though through a doorway to the rural past. These prepare the ground for the film’s concern with dislodging tenacious images of England’s countryside as a white preserve.

The film’s first black face appears as the outskirts of London are reached. A mixed-race woman opens a garden umbrella outside a riverside pub. This is followed by a brief close-up of a smiling Black schoolboy before the camera pans across a field and hovers above an Intercity 125 train. Inside the carriage, an Indian family is seated at a table. The teenage daughter reads the official gold-coloured guide to the opening ceremony.5 A split-second shot of a Black cricketer, a bowler – dressed in traditional cricket whites with a cloth cap and spotted necktie – appears at a culturally sensitive moment, coming straight after shots of the Oxford-Cambridge boat race and the Eton boating song, both of which epitomise elite expressions of Englishness. In this context, the image of an early 20th-century Black bowler is disruptive, not merely reminding supporters that Britain’s colonial masters have frequently been beaten at their own game,6 but because the way he is dressed suggests a historical, rather than recent, Black presence in the countryside. Whether Boyle intended it or not, the image is more complex than it might seem. There was a class tradition where the Marylebone Cricket Club employed professional bowlers as servants to bowl at the gentlemen batsmen,7 and the Caribbean trope of the Black fast bowler and the white batsman persisted at least into the 1930s.8 The only Black cricketers on a 1900 West Indies tour to England were bowlers; all the batsmen were white. But the presence of a Black cricket player is historically appropriate. There was the famous Indian prince, Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji (1872-1933) who played for both Sussex and England between 1895-1904;9 there was Charles Ollivierre (1876-1949) who came with the 1900 West Indian team to England, and thereafter was recruited by the Derbyshire County Cricket club for whom he played between 1901 and 1907;10 and there was Kumar Shri Duleepsinhji (1905-1959), another Indian prince who also played for Sussex and England between 1929 and 1931.11 But almost certainly the film’s reference is to Learie Constantine (1901-1971), a Trinidadian all-rounder who toured England with the West Indies in 1923 and later played in the Lancashire League (perhaps explaining the cloth cap). In Lancashire, Learie Constantine was an immensely popular figure who immersed himself in local radical Labour politics. He later became a formidable influence on racial equality campaigns and legislation. Eventually he became Britain’s first Black peer.12 Yet the Black cricketer might have been seen by the Olympic audience that night as unlikely because this figure challenges collective historical amnesia about Black people’s longstanding and influential association with England’s countryside as well as the nation more generally. In fact, as this book explores, the history of Black and Asian people in Britain before the 1940s was almost as much rural and coastal as it was urban.

That night in July, ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ was the first live spectacle in the stadium. 7,346 square metres of real grass and crops simulated a pastoral, pre-industrial setting. Farmers and milkmaids tended sheep, horses, ducks, goats and geese. The scene featured a cricket match – again including a Black bowler in cricket whites – and four Maypole dances, with a handful of Black children. Actors moved around the white cottages and hedgerows to the accompaniment of choristers singing Parry’s ‘Jerusalem’.

On the surface, the Official Guide commentary on ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ seems relatively innocuous:

This is the countryside we all believe existed once. It’s where children danced around the Maypole and summer was always sunny. This is the Britain of The Wind in the Willows and Winnie the Pooh.13

The statement is actually a gentle reproof which rejects outmoded visions of the past. England’s rural idyll is presented as a nostalgic falsehood (‘the countryside we all believe existed’), a falsehood fed to us by the classic stories we heard as children. This fiction, the commentary implies, has left a rose-tinted imaginative legacy (‘summer was always sunny’). Depictions of idyllic rural childhoods are – the booklet suggests – freighted with nostalgia, a beautiful lie. This lie is undermined by the commentary’s appeal to our contrasting experiences of overcast skies or recurrent summer rain. The use of the singular (‘the Britain’) immediately implies that there are multiple ‘Britains’ with which its citizens variously identify.

From a historical perspective, Boyle did well to place Black Britons in the pre-industrial countryside, since he offered an alternative lens through which to view the nation’s rural past. Yet, in Boyle’s presentation (although the Black cricketer probably recalls Constantine), the presence of Black maypole dancers, farmers and milkmaids in the stadium cannot be seen as wanting to reflect any historically genuine Black rural presence in the 18th and 19th centuries. Rather it is presented as a utopian dream for the future (‘we will build Jerusalem’). Boyle might easily have drawn on established historical knowledge to justify his vision of a multiracial rural past. Instead, Boyle’s ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ is a well-meaning reaction against elitist and exclusive forms of English self-fashioning more than any genuine acknowledgement that – to quote Caroline Bressey – ‘black histories of England are intimately connected to the rural’.14 Wills, parish records and court records testify to this presence. So do paintings. Few exhibition halls would be big enough to exhibit all the paintings that include African and Asian servants which currently hang in historic houses.15 As the words of the Parry’s anthem ‘Jerusalem’ imply, the scene advocates national unity by means of an inclusive collective return to nature. The countryside is ‘for everyone’. Boyle’s multicultural vision of rural England was a healing gesture, given the use of the ‘green and pleasant land’ metaphor to the anti-immigration speeches of Conservative MP Enoch Powell in the late 1960s and 1970s and – by the time of the London Olympics – the UK Independence Party, which was then at its height of popularity.16 In Boyle’s contemporary response, however, ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ missed the opportunity to justify its representation of a historical Black presence when it failed to provide genuine references to this presence in England well before the days of empire.

Had ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ had greater historical precision, it might have been less of an easy target for the resultant hostile reviews in blogs and newspapers. ‘Pandemonium’, the Industrial Revolution scene in the pageant – named after John Milton’s ‘hell’ and Humphrey Jennings’s book with that title17 – contains black industrialists in top hats – a phenomenon without any historical justification – which provoked Scott Gronmark to write: ‘I knew we were in for some social re-engineering when a black Victorian industrialist popped up complete with top hat in the Kenneth Branagh… section.’18 ‘Pandemonium’ underlined the fact that England’s historical Black presence was presented as fanciful rather than real.

Boyle may have intended to include everyone, but the reality of the event was very different. Despite the ceremony’s celebration of diversity, Britain’s largest black newspaper, The Voice, was denied access by the Media Accreditation Committee on the grounds that there was only space for 400 journalists to cover the ceremony. A further irony was that The Voice offices are situated close to the Olympic stadium.19

One of the 900 million-strong audience members was the Conservative MP, Aiden Burley, who kept up a running commentary of his responses to ‘Isles of Wonder’ on Twitter. After viewing ‘Green and Pleasant Land’ he tweeted: ‘The most leftie opening ceremony I have ever seen – more than Beijing, the capital of the communist state!’ His later, now notorious, tweet expressed affront at the presence of so many Black people in the artistic reconstruction of Britain’s past:

Thank God the athletes have arrived! Now we can move on from leftie multi-cultural crap. Bring back Red Arrows, Shakespeare and Stones!20

The tweet caused a political row, prompting Burley to offer an explanatory tweet: ‘Seems my tweet has been misunderstood. I was talking about the way it was handled in the show, not multiculturalism itself.’ On Saturday 28 July, The Guardian’s Nicolas Watt commented:

Burley’s outburst will fuel suspicions that some members of the Conservative party have unreconstructed views which fail to recognise the pivotal contribution to society made by black and minority ethnic Britons. Boyle illustrated this with a section devoted to MV Empire Windrush, the ship which brought many passengers from Jamaica to start a new life in Britain.21

While these words are offered in defence of multiculturalism, they promote an inaccurate but widely-held belief that the postwar era was the moment when black people arrived in Britain. Watt fails to address the deeper cause of Burley’s offence, hinted at in his defensive tweet: ‘I was talking about the way it [multiculturalism] was handled in the show’ [my italics]. What evidently offended Burley was the vision of Black people in the countryside, a phenomenon that he saw as incongruous. Burley’s tweets imply that the countryside has always been, and ought to remain, a white sanctuary. In the same vein, and on the same weekend, an anonymous tweeter wrote the following response to the ceremony: ‘Apparently, in the pre-industrial revolution bit, some of the white sheep were pretending to be black sheep’.22 Whiteness, the logic goes, is native to the English countryside: anyone else is an outsider and an impostor. Other commentators, too, characterised ‘Isles of Wonder’ as a farcical minstrel show. Gronmark wrote in his blog: ‘I’m surprised Boyle didn’t ask Paul McCartney to black up to sing “Hey, Jude”’.23 Gronmark’s irritation is similarly triggered by the ceremony’s portrayal of devolved Black Britishness. A stadium-based choir composed of black and white children sing ‘Jerusalem’ but hand over to their Northern Irish counterparts standing on the Giant’s Causeway. Next, the camera visits a third children’s choir positioned near Stirling castle. As they offer a regionally-accented rendition of ‘Flower of Scotland’, the camera pans across the front row, where a Black boy is prominently placed. As another implicit celebration of blackness in a semi-rural location, this again provoked Gronmark, who complained that, in Boyle’s vision of multiculturalism, Black people were ‘punching well above their demographic weight’. He similarly objects to the presence of a Black Scottish singer: ‘A Scottish female singer with an extremely unsuitable voice later sang “Abide With Me”, obviously she was black too.’24 Like Burley, Gronmark objects to the way multiculturalism was depicted. The implicit suggestion is that the countryside does not belong to all.

As this book explores, the countryside is widely viewed as having everything to do with whiteness and little to do with empire, and suggestions to the contrary typically encounter strong opposition. A recent Daily Mail article about the National Trust’s attempts to address its colonial connections provoked nearly 500 comments, all hostile.25 One reader wrote, ‘There is a coordinated attack on British values, culture [and] heritage’, conveying a belief that the heritage sector ought to promote monocultural versions of the rural past. Another reader called Rosie accused the National Trust of starting a ‘campaign to make Britons ashamed of their glorious heritage.’ For another reader, the idea of a rural white preserve is enduringly potent: ‘It is high time all the descendants of slaves returned to the birthplace of their ancestors and stayed there, as they are not doing themselves any favours trying to besmirch our ancestors and heritage.’ Made in the context of country houses, this comment indicates that what is being disturbed is an unsubstantiated illusion of historic rural England as having been self-contained, isolated from the world.

Other Mail readers of the article accused the Trust of trying to ‘change the past’. One comment reads: ‘The National Trust is supposed to preserve our history, not change it.’ In the mind of this reader, and many others who left similar comments, to revisit this aspect of the past is to falsify and corrupt history itself.

But to preserve without asking new questions is to fossilise. If the heritage sector is a custodian of history, it is incumbent upon professional interpreters of that history to explore stories which emerge from new research. Historic houses predominantly tell the story of family, but such properties have many more stories to tell.26 One Mail reader asserted: ‘The fact is that there were never any slaves in Britain.’ To counter this denial is to be met with suspicion: the attempt is seen as ideologically motivated rather than evidence-based. There is widespread reluctance to hear local historical evidence of colonial links, such as the 1771 slave ‘auction’ in Lichfield in which the Aris’s Gazette advertised the sale of ‘a NEGROE BOY, supposed to be about ten or eleven years of Age’.27 There are hundreds more escaped slave notices recorded by the Runaway Slaves project at the University of Glasgow.28 In one sense, however, Mail readers’ remarks on the subject of the Black rural presence missed the point. As the article made clear, the heritage sector is primarily interested in the legacies of colonialism (not just slavery) – financial, cultural and curatorial. For many, simply researching colonial connections is an affront. When Cambridge University announced its intention to investigate its slavery links, the news was widely condemned. ‘Seldom’, David Olusoga wrote, ‘have so many people taken to print and the airwaves to make the case for academic incuriosity.’29 Moreover, when the National Trust published its report on colonialism and historic slavery connections in September 2020, the Leader of the House of Commons, Jacob Rees-Mogg, objected in a parliamentary speech, the Culture Secretary condemned the report in the press, the Common Sense Group of Conservative MPs called a debate on ‘The Future of the National Trust’ in Westminster Hall and the Charity Commission wrote to the National Trust to ask ‘how the trustees consider its report helps further the charity’s specific purpose to preserve places of beauty or historic interest.’30 Widespread attempts to repress historical research – and to incorporate colonial history into heritage sites – are often made in the name of free speech and celebrating the nation’s past.

In response to one of many Daily Mail articles on the subject, one objector states, ‘it is history and should be left there’ [my italics].31 Another writes: ‘nothing can be done to change history, so what in earth [sic] is to be gained?’ Yet these comments suggest that, in this context, the term history can actually be taken to mean ‘unpalatable elements of the national story’. What require preserving, the logic goes, are familiar, established accounts of the past. Specialists in British imperial history are viewed as ideologues, trespassers on hallowed ground. Research findings on this topic are presented as political and emotional rather than rational in motivation. Another comment under a Mail article declared: ‘this self-punishment must stop’. Another calls it ‘self-flagellation’. Such statements communicate unexamined emotional responses, an unnamed fear that new facts threaten old ones. Given the paucity of information in the school curriculum on Britain’s four colonial centuries that most British adults have received, it is unsurprising that it should come as a shock that the countryside has so many colonial connections.

Such comments reveal inconsistent attitudes to the past. As the historian Rajwinder Singh Pal remarks, few Britons would wish to destroy the sites of German Nazism or Italian Fascism. Neither are there objections to commemorating Waterloo, or even Peterloo.32 Olusoga observes that ‘the parts of the past that it seems unhealthy to dwell on tend to be those in which nonwhite people were exploited or exterminated. It’s always too long ago or not appropriate.’33 The idea that new information amounts to ‘politically correct revisionism’ (as one Mail reader asserted) – actual falsification of the past – reminds us that England’s ‘green and pleasant land’ is sensitive terrain. This book attempts to explain the sources of rural mythologies themselves.

It is worth pointing out that the views noted above do not exist only on the pages of The Mail. The Telegraph has run many negative articles about the 2020 National Trust report since its release, and ran an opinion piece entitled ‘National Trust must listen to members’ in which it argued that questions ‘about the wisdom of the Trust’s “woke agenda” need to be heeded, not ignored.’34 Academic historians such as Andrew Roberts have offered more sophisticated versions of the same proposition, selling many books promoting his view of the benefits (with a few regrettable lapses) of colonialism.35 Roberts, and many of the commentators in The Mail, hold the view that we cannot judge the imperial past by the values of the enlightened present. One descendant of a family who built a country mansion from the proceeds of active involvement in transatlantic slavery said, ‘raking through the past is not particularly helpful’, and implied that the existence of slavery was a blot on everyone.36 Perhaps, but it is worth remembering that slave-ownership involved 6% of the British population (those whose claims show up in the emancipation compensation records). This is only a slightly greater percentage of the population than those who formed the electorate before 1832 and who could have chosen the MPs who decided the fate of slavery.37 It is an argument that is profoundly ahistorical, as is shown in Jack P. Greene’s Evaluating Empire and Confronting Colonialism in Eighteenth Century Britain (2013) and Priyamvada Gopal’s Insurgent Empire: Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent (2019). Throughout the colonial period, there were always well-informed and ethically unambiguous critics, not merely of empire’s more indefensible outrages (though there were always defenders to be found), but also of the sources of its profits from slavery and the activities of the East India Company.

The historian Catherine Hall has pointed out that, even after abolition and emancipation, British literary figures with (little-discussed) links to slave ownership applied their writing talent to present versions of the past that justified chattel slavery and promoted racial hierarchies. Thomas Carlyle’s infamous racist tract, Occasional Discourse on the Nigger Question (1853) asserted that emancipation had been a huge mistake. Carlyle was not alone. Following the killing of African Jamaican peasants after the Morant Bay rebellion of 1865 on the order of Governor Eyre, the ‘cream’ of literary England took Carlyle’s side when he set up a committee to defend Eyre from liberals such as Charles Darwin and John Stuart Mill who wanted to see him prosecuted for murder. Charles Dickens, Lord Alfred Tennyson, Charles Kingsley and John Ruskin were amongst those who supported Carlyle in defending Eyre.38

Priyamvada Gopal records similar divisions in Britain over the bloody aftermath of the Indian rebellion of 1857, between those who approved of the retribution visited on suspects who were blown to pieces from the mouths of English cannons, and those like the Chartist Ernest Jones who believed that the rebellion was a justified struggle for nationhood.39

I have discussed at length the phenomenon of Boyle’s film and grand Olympic pageant and the response to it because it illustrates that, for a long while, Britain has been at a crossroads. There have been recent attempts both to open up and to resist a discussion about the way Britain has been shaped by its history as an imperial power. The corollaries of once being an imperial power do not simply concern the presence of people from the former empire in the ‘motherland’, but the imprint of empire on contemporary attitudes to nationhood, sovereignty and the idea of (English) exceptionalism. Danny Dorling and Sally Tomlinson’s book, Rule Britannia: Brexit and the End of Empire (2019) makes some of those connections. The choice between nostalgia and egalitarianism is also identified by Paul Gilroy in the subtitle of his book After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture (2004). My book weighs in on the side of a rich, convivial culture.

This book attempts to bring three points of departure into connection and dialogue. The first is the phenomenon of empire and colonisation as a set of activities at home and abroad – administrative, economic, military, political, and rhetorical. The second point of departure is the relationship between empire and rural Britain. Here this book unites discussions by researchers of the East India Company and Black Atlantic studies. It makes sense to join these often distinct scholarly domains because the worlds they study are often interwoven. Stately homes illustrate this point. Through successive generations and owners, many properties have links with both the East and the West Indies, which is the case with many of the 93 houses named in the 2020 National Trust report into its places’ colonial links. The histories of persons are also often intertwined. In Children of Uncertain Fortune, Daniel Livesay tells the story of the Jamaican plantation owner, John Morse. Three of his mixed-race children – the descendants of an enslaved mother – moved from Jamaica to London and, from there to India, where the son worked for the East India Company in Calcutta. The daughters also travelled from London to India, each marrying East India Company servants (officials) in Calcutta, coming back to England and featuring in a painting by Johann Zoffany called The Morse and Cator Family (1784).40 The third point of departure is the long historical presence of Black and Asian people in Britain, including their particular relationship to the countryside. From these three starting points, the book sets out to explore the connections between historical studies and imaginative literary attempts to rethink English rurality. It demonstrates how Black British and British Asian writers (who are inevitably also readers) have addressed and challenged a sense of rural exclusion within the context of shifting sensibilities about the countryside in writing from the sixteenth-century to the present.

Writing in the Footsteps of Pioneers

As in any book of synthesis, I have intellectual debts. These include C.L.R. James’s book The Black Jacobins (1938) which provided an influential account of the Haitian revolution, the first significant countermovement for colonial freedom in the modern Atlantic and global world.41 The book’s original preface summarised the achievements of the enslaved, led by Toussaint L’Ouverture: ‘The slaves defeated in turn the local whites and the soldiers of the French monarchy, a Spanish invasion, a British expedition of some 60,000 men, and a French expedition of similar size under Bonaparte’s brother-in-law.’42 Inspired by this account, Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery (1944) argued that slave-produced wealth allowed Britain to accumulate the necessary capital for the industrial revolution. Slave-trading stimulated manufacturing through the goods used as barter for enslaved people and the manufacture (in Birmingham in particular) of the chains and items of torture used to discipline enslaved people.43 Though some subsequent historians dismissed this as an exaggerated claim, Williams’s thesis has received well-documented defences in a book such as Joseph E. Inikori’s Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England (2002).44 More recently, the work of Nicholas Draper, The Price of Emancipation: Slave Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery (2010) demonstrates that the profits of slavery did not end after its abolition and that the direct benefits of slave-ownership produced further capital, some of which was invested in infrastructural projects such as railway construction. Draper’s book and a major research project led by Catherine Hall, called Legacies of British Slave-Ownership (2014), suggests that Williams’s thesis was substantially correct.45 The project and its accompanying database identify the recipients of £20M worth of compensation money paid to former slave-owners from around 1837 into the 1840s. Administered by the misleadingly-named Slave Compensation Commission, this enormous sum, estimated at £17 billion in today’s money, was finally paid off by the British taxpayer in 2015.46Legacies of British Slave-Ownership allows researchers to trace the money received and spent by the recipients of this compensation money. Catherine Hall observes: ‘all the way through to the 1830s and indeed beyond we can see wealth derived from slave-ownership being redeployed into country-house building, connoisseurship and philanthropy in Britain’.47 Recent research has extended work on empire into family histories such as Katie Donington’s work on the slave-owning Hibbert family, which reveals how power and wealth was passed down the generations.

The history of the careers of five members of the Beckford family neatly brings together the complex of wealth, power, literary idealisation, sporting recreation and the aestheticised proceeds of fortunes gained from slavery. Peter Beckford (1643-1710) was the founder of the dynasty as acting governor and owner of around twenty estates in Jamaica. His grandnephew, William Beckford (1709-1770), inherited Jamaican estates, but himself lived most of his life in London, when he was not at his country estate, Fonthill, in Wiltshire. He was reputed to be London’s wealthiest citizen, became lord mayor twice and ardently supported the bourgeois liberties of the subject against the crown, and the colonist’s right to enslave colonised people.48 His son, also William (1760-1844), was the author of what is now seen as the founding novel of the queer gothic, Vathek (1786). He was the aesthete who squandered the wealth accumulated by his father, collecting art and building the gothic folly of Fonthill Abbey, most of which collapsed in 1825 only eighteen years after it had been built.49 There was Peter Beckford (1740-1811), grandson of the Jamaican acting governor, who also inherited Jamaican estates but never visited them. He spent his time and money engaged in rural sports and wrote one of the first books about hunting. He was reputedly much embarrassed by the reputation of his cousin, the gothic writer, who had at one time to flee from England because of a homosexual scandal.50 There was a third William Beckford (1744-1799), the illegitimate nephew of the lord mayor, who inherited five smaller sugar estates and lived in Jamaica for 13 years, failed as a planter and was imprisoned for debt in London in 1786. To earn some money he wrote two volumes of A descriptive account of the island of Jamaica (1790), which combined an ardent defence of slavery with a pastoralisation of the plantation landscape, that is ‘chiefly considered in a picturesque point of view’, meaning he represented it as if it had been an English landscape.51 There was a further Beckford, Henry, an ex-slave and abolitionist, who appears in the painting of an antislavery convention in London, by Benjamin Robert Haydon (1840).52 Henry Beckford was a deacon in St Ann’s Bay, Jamaica, the location of many of the Beckford estates. The Forebears website tells us that one in every 330 Jamaicans (8689) is a Beckford.53

I am by no means the first to explore the relationship between empire, slavery, the countryside and British literature. Raymond Williams’s study, The Country and the City (1973), was pioneering in the way it connected the ideas of C.L.R. James and Eric Williams to fundamental ideas about land and its relationship to capitalist development.54 Focusing on English stately homes as the subject of a long tradition of literature, Williams writes: ‘important parts of the country house system, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, were built upon the profits of [imperial] trade.’55 At the time of writing The Country and the City, Williams was not able to elaborate very precisely upon these connections, but since then, as noted above, country house historians have identified specific and multiple links with both Caribbean and East India Company wealth.

Following the work of Raymond Williams, there has been an increasing trend in British imperial history to see colonial profits as being as much a rural as an urban phenomenon. In Slavery and the British Country House (2013), Andrew Hann and Madge Dresser argue that country houses are a potent ‘symbol of …connoisseurship and civility… and an iconic signifier of national identity’.56 This is an argument explored across a wider range of cultural practices in Simon Gikandi’s important book, Slavery and the Culture of Taste (2011). Gikandi’s book argues that far from being anomalies, the brutality of slavery and the promotion of polite culture (of manners and concern with aesthetics) were both deeply intermeshed in ideas about race and social and economic development. These were the ideas that justified the colonisation of the lands of other peoples who were believed not to have any sense of property or civility, and the right of those people who had those qualities to own Africans as chattel slaves.57 Further critical contributions have been made to discussions of the countryside in James Walvin’s Fruits of Empire: Exotic Produce and British Taste, 1660-1800 (1997); Stephanie Barczewski’s Country Houses and the British Empire, 1700-1930 (2014) and David Olusoga’s Black and British: A Forgotten History (2016). These authors reveal rural Britain’s colonial connections to be many and various.

This book also refers to work on writers’ social station and gender, in publications such as Donna Landry’s The Muses of Resistance: Laboring-Class Women’s Poetry in Britain, 1739-1796 (1990) and William J. Christmas’s The Lab’ring Muses (2001). It includes work that investigates the literary traditions of pastoral and georgic such as John Gilmore’s The Poetics of Empire (2000) and Rachel Crawford’s Poetry, Enclosure, and the Vernacular Landscape 1700-1830 (2002). Other critics have connected writers’ perceptions of landscape to actual agricultural change and to the relationship between land and empire. Helpful contributions here come from Beth Fowkes Tobin’s Colonizing Nature (2005), Jill H. Casid’s Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (2005), and in particular Saree Makdisi’s Romantic Imperialism: Universal Empire and the Culture of Modernity (1998). Increasingly, rural writing has been read in the context of visual culture, especially the aesthetics of the picturesque and the sublime, aesthetic ideas that still influence the way we see the countryside today. John Barrell, for instance, in The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place: An Approach to the Poetry of John Clare (1972) identifies a shift from general and idealised perceptions of landscape, to portrayals of the rural world that are individual and specific, a shift that he locates in the writing of John Clare.

For me as for many other authors, Peter Fryer’s respected work Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain (1984) remains a key foundational text.58 Fryer’s book was by no means the first. Before it came Paul Edwards’s first modern edition of Equiano Olaudah’s autobiography in 1967.59 There was also James Walvin’s The Black Presence: A Documentary History of the Negro in England (1970) and Edward Scobie’s Black Britannia: A History of Blacks in Britain (1972), the first panoptic history, which goes back to the Elizabethan period, marking the beginnings of British colonial activity.60 There was also F.O. Shyllon’s Black Slaves in Britain (1974). But though not the first, Fryer’s book reached and influenced more readers and is widely acknowledged as having demonstrated how long Black people have resided in Britain. Staying Power begins with Roman centurions on Hadrian’s Wall, and only a relatively slim section of the book postdates the 1948 arrival of the SS Empire Windrush in Tilbury Dock, an event which is persistently and incorrectly held to have inaugurated Black Britishness. Important subsequent texts include Gretchen Gerzina’s Black England. Life Before Emancipation (1995), which also explores the rural black presence. Another foundational work is Rozina Visram’s Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: Indians in Britain, 1700-1947 (1986),61 the first book to deal with the historical experience of South Asians in the British Isles.

As Fryer suggested, it was not always the case that black people came to Britain as a consequence of empire. As Miranda Kaufmann argues, the lives of those she writes about in Black Tudors: The Untold Story (2017) fall outside the colonial framework. They include a royal trumpet player, a diver, a porter, a silk-weaver and a mariner.62 Research about 18th century England and Wales makes a related point about ordinary lives. Kathleen Chater’s book Untold Histories: Black People in England and Wales during the period of the British Slave Trade c. 1660-1807 (2009) draws extensively from official records to argue that Black people led active working lives in a range of professions. They were tradespeople, shopkeepers, government officials and entertainers. They did not always live ‘in the shadows of… aristocratic famil[ies]’.63

Going even further back, developments in isotope technology and radio carbon dating have led archaeologists to take ancient British skeletons out of cupboards, only to discover that ‘white’ bones are sometimes African bones, including those of some of the seamen who perished with the Mary Rose in 1545.64 This ‘archaeology of Black Britain’ is providing a growing body of evidence to suggest that parts of the countryside – in this case the area around York – once had larger black populations than they do today.65 The archaeologist Rebecca Redfern writes that Roman Britain was ‘a highly multicultural society which included newcomers and locals with black African ancestry and dual heritage, as well as people from the Middle East’.66 Scientists have studied well over a hundred skeletons from the Roman period and found that, contrary to the idea that pre-modern populations were immobile, some British towns had migrant populations – from other cities and sometimes other countries – of up to thirty percent.67

A rurally-based Black British writer, the poet Louisa Adjoa Parker has documented the Black presence in Dorset’s Hidden Histories (2007). Kevin Le Gendre’s Don’t Stop the Carnival: Black Music in Britain (2018) profiles the career of the virtuoso violinist and orchestral composer, Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775-1835) who was part of a significant population of Black people on the southwest coast. They settled in that area as part of its military presence, at a time when Black people were commonly recruited into the army and navy as musicians (Emidy was press-ganged for this purpose). Emidy rose to be leader of the Falmouth Harmonic Society and the Truro Philharmonic. As a sad note on the limits of possibility for even a virtuoso, Emidy’s introduction to London society seems to have foundered on his blackness, he having been described by one member of this elite as ‘the ugliest Negro I have ever seen.’68

Repressed histories only appear contentious because they feel unfamiliar. Until recently, the histories and legacies of Britain’s colonial era seem to have all but faded from wider public memory. This is especially true of the nation’s involvement with transatlantic slavery. In Devon and the Slave Trade, for example, Todd Gray points out that the most authoritative text on the county’s history, written by W.G. Hoskins (Devon and Its People (1959)), fails to mention slavery even though England’s first slave-trading vessels set sail from Plymouth harbour in 1562.69

For decades, knowledge of African, Caribbean and Indian connections have been restricted to the academic field of British imperial history. Now, the wider public is awakening to these legacies. It is learning, for example, that not only did Sir Francis Drake participate in John Hawkins’s third slave-trading voyage on a royal ship, but – as Miranda Kaufmann discovered – he depended upon an African circumnavigator, Diego, to guide and advise him. Diego was not the only African aboard Drake’s ship. The Golden Hind carried an enslaved African named Maria, whom Drake eventually abandoned on an Indonesian island. She was pregnant and there was no water source. As Kaufmann points out, this cruelty is likely explained by the need to keep up appearances. Had the protestant crew returned to Plymouth with a heavily pregnant woman, the captain and his sailors would have had some explaining to do.70

Later periods tell their own varied stories. A key rural protagonist is George Nathaniel Curzon, whose name adorns many Derbyshire buildings, including Curzon Primary School.71 His childhood home, Kedleston Hall, has an architectural counterpart in India, where it was once Government House in Calcutta.72 The Curzon example connects empire with domestic history, since British rule over colonial India was used as a pretext for Curzon’s opposition to women’s suffrage in his home country. In a pamphlet, Curzon argued that giving women the vote would demean Englishmen in the eyes of Indians. New information disturbs established versions of the past. Two princesses at West Midland’s Wightwick Manor connect with forgotten stories about Indian women’s contribution to Britain’s suffragette movement, while also reminding us that it was a global, not merely a local, movement.73

Places tell their stories, but so does cultural production. Classical music is often used to evoke the English countryside, particularly in heritage films and costume drama. Yet this music, too, is implicated in empire. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) invested in the slave-trading Royal African Company and there are links between 18th-century music and slaveownership. Musicologist David Hunter discovered that the profits of slavery paid for the purchase of musical instruments, and performers’ fees for London operas. He also found that the Beckford family, which made its money from sugar plantations, invested in an expensive new organ for the palladian mansion at Fonthill and bought other valuable musical instruments.74 But there were also 18th century Black musicians and composers, such as Ignatius Sancho (1729?-1780) and Joseph Emidy, as noted above.