Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

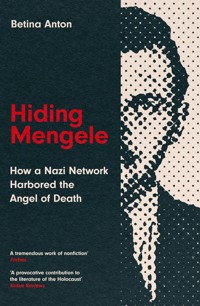

Read the international sensation already translated into 10 languages! Unearthing the network that hid the 'Angel of Death,' the infamous Nazi doctor who escaped justice for more than three decades. In 1985, Betina Anton watched Brazilian authorities apprehend her kindergarten teacher for allegedly using false documents to bury in secrecy the remains of Josef Mengele, known worldwide for cruel human experiments and for sending thousands to the Auschwitz gas chambers. Decades later, as an experienced journalist disturbed by the mysteries surrounding the departure of Austrian expat Liselotte Bossert, Anton set out to find her and see if the rumors were true. She could not imagine how deeply into Mengele's life-on-the-run her investigation would take her. Josef Mengele was a fugitive in South America for thirty-four years after World War II, sought by Israeli secret service and Nazi hunters. Hidden for half that time in Brazil, thanks to a small circle of expatriate Europeans, Mengele created his own paradise where he could speak German with new friends, maintain his beliefs, stay one step ahead of the global manhunt, and avoid answering for his crimes. Translated from the Brazilian Tropical Bavaria edition and based on extensive research, including revelatory interviews and never-before-seen letters and photos, Hiding Mengele is a suspenseful narrative not only haunted by the doctor's horrific actions but also by the motivations driving a community to protect an evil man.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 462

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Arrangement with Diversion Books in the UK in 2025 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

ISBN: 9781837733002

eBOOK: 9781837733019

Copyright © 2025 Betina Anton

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Design by Neuwirth & Associates, Inc.

Photo research by Gabriella Gonçalles

Printed and bound in the UK

TO PABLO AND HELENA

Contents

PROLOGUEHow to Bury a Body Under a False Name

CHAPTER 1Investigating a Dangerous Case

CHAPTER 2Reuniting Mengele’s Twins

CHAPTER 3In Search of Justice

CHAPTER 4Keeping Secrets

CHAPTER 5A Rising Scientist in Nazi Germany

CHAPTER 6The Kindly Uncle

CHAPTER 7Appetite for Research

CHAPTER 8Mengele’s Promotion

CHAPTER 9The Liberation of Auschwitz

CHAPTER 10The Nuremberg Trials

CHAPTER 11Nazis in Buenos Aires

CHAPTER 12Operation Eichmann

CHAPTER 13The Loyalty of Nazi Friends

CHAPTER 14No Rest in Serra Negra

CHAPTER 15Tropical Bavaria

CHAPTER 16Life on the Edge

CHAPTER 17The Final Hunt

CHAPTER 18Exhumation

EPILOGUELiselotte’s Last Words

A Note on Sources

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

PROLOGUE

HOW TO BURY A BODY UNDER A FALSE NAME

BERTIOGA, BRAZIL. FEBRUARY 1979

It was a beautiful afternoon, and Peter hadn’t yet left the house that day. The doors and windows were closed almost all the time, even in the stifling summer air.1 The neighbors barely knew who was inside. He was very reserved and didn’t like strangers. He had arrived alone from São Paulo the day before, after a tiring bus ride through tortuous roads and a long ferry crossing. His friends Wolfram and Liselotte Bossert and their children were already waiting for him. The old man loved those kids: Andreas was twelve, and Sabine fourteen. Even so, he hesitated for a while before accepting the invitation to spend time with them in Bertioga. He said he was tired. He only agreed to go because he believed that his life was already at an end.2 Lately, he had been irritable, nervous, and before his trip he had had a fight with Elsa, his former maid. The reason was that he liked her but it wasn’t reciprocated. One more reason to relax on that hot afternoon. He decided to leave the summer house to take a swim in the sea. The whole Bossert family accompanied him to the beach. They were so close that they seemed to have blood ties. He’d known the kids since they were little, and everyone, even the adults, called him “Uncle Peter” or just “Uncle.”

All five of them could speak Portuguese fluently, but always preferred to talk in German, their mother tongue. Uncle Peter was from Bavaria in southern Germany. Wolfram and Liselotte Bossert were Austrian. The two were already married when they decided to come to Brazil in 1952, attracted by botany, especially her, who had always loved the beauty of plants and venturing into nature. They also knew that there was a large community of German speakers here, which would help open doors for them in an unknown country. They had left Europe during the Cold War because they feared another armed conflict on the continent. At the time, there was a climate of uncertainty in Austria, which was still occupied by the Allied forces. Not to mention the fact that the country sat right next to the Iron Curtain, the imaginary line separating the capitalist and communist worlds. All this tension added to the fact that Liselotte and Wolfram had faced World War II just a few years earlier and believed they could not bear an experience like that again.

The Allies’ nightly bombings on Graz, the city where Liselotte had lived and the second largest in Austria, left her heart “irregular,” as she used to say. From that time until the end of her life, she felt that her heartbeat never returned to normal. When Adolf Hitler invaded Poland and started the war, she had been an eleven-year-old schoolgirl. The conflict shook her world. Her uncles had died fighting for the Third Reich.3 Wolfram had also fought for the German Army, without ever rising above Scharführer, the equivalent of corporal in the military hierarchy. Uncle Peter had risen much higher, and Wolfram admired him for that: he had reached the rank of Hauptsturmführer, the equivalent of captain. Moreover, he was part of the dreaded SS—or Schutzstaffel—a special force that was created to provide security for the leaders of the Nazi party and became an elite group with its own army.

However, it wasn’t Uncle Peter’s work in the SS or at the front that made him world-famous years later, but rather his work as a doctor in the Auschwitz death camp. Josef Mengele was his real name, something that no one could know then. That wasn’t something to talk about in front of other people, especially the children, who had no idea about Uncle Peter’s dark past. What mattered at that moment was getting to the sea. The beach was about a thousand feet from the house that the Bossert family rented every summer from another Austrian, Erica Vicek, who called herself a “staunch anti-Nazi.” She didn’t have the slightest idea of who the special guest that her tenants used to host really was.

At the end of the 1970s, Bertioga was isolated from the rest of the world, and getting there required patience. Access was via the island of Santo Amaro, in Guarujá. From there you could take a ferry across the channel. Travelers couldn’t be in a hurry, as the short journey could take hours, depending on the ferry schedule. This didn’t discourage many Europeans who lived in Brazil and enjoyed the coast when on vacation. In addition to the Austrians, some Germans, Swiss, Italians, Hungarians, and French had vacation homes there. It was an opportunity to relax in a pleasant and peaceful place. Cars were left unlocked, the windows and doors of the houses were open; there were no worries there, unlike life in São Paulo or in Guarujá next door, with its trendy beaches and much more expensive real estate. Many vacationers liked to take advantage of the quiet to spend hours fishing for mullet, of which there were plenty in Bertioga, as Hans Staden had described more than four hundred years earlier. The German explorer was the first person to publish a book about the beauties and dangers of that region full of indigenous people in the sixteenth century. Staden certainly spoke from experience, for he had been captured by the Tupinambás, who were cannibals, and narrowly avoided ending up in the cauldron. Another favorite pastime during those long summer seasons was card games. At least once a week, a group of Europeans of different nationalities got together to play, and even back then rumors circulated that Nazis were hiding in the area.4

Bertioga’s main beach, Enseada, wasn’t exactly the Côte d’Azur. The color of the sea was almost brown, an effect caused by the decomposition of the rich Atlantic Forest vegetation that covers the entire area. The tourists didn’t mind the shade of the water, which from a distance looked dirty. The charm of the place seemed to be something else: the sea was good for swimming, unlike so many beaches on the coast of São Paulo. With a bit of luck, on some days it formed a perfect pool for children. On other days, the sea could get rough and, during vacation periods, it was not uncommon for lifeguards to report drownings. The long beach, over seven miles from end to end, with a wide strip of sand, was ideal for playing soccer, as some of the men were doing that Wednesday afternoon.

While the ball was rolling in the sand, the Bosserts and Uncle Peter went into the water. The sea currents soon began to pull, and Liselotte preferred to go to the shallows with her children. Uncle Peter swam very well, but that day Andreas saw him raising his arm, asking for help. He seemed to be drowning. Liselotte thought her friend had suffered a stroke, and Wolfram rushed to his aid. When he grabbed him, the old man was already gasping for breath. Andreas ran down the beach to get a Styrofoam float to throw to his uncle. Other people also tried to help. Two lifeguards, who were at the only post on the beach over a quarter-mile away, saw the movement and came running. Wolfram had already managed to pull Uncle Peter into waist-deep water, but he was still struggling to get out of the sea. The rescuers had to drag them both out. They performed chest compressions to try to revive Peter, who was unconscious by then, but it was too late. He was already dead.

Someone called for an ambulance. From there, they announced the obvious: there was nothing more to be done.5 Despair fell upon Liselotte. She hugged the body and didn’t want to let go.6 Her husband was feeling unwell because he himself had almost drowned trying to save his friend. An ambulance took Wolfram to the hospital, while Liselotte stayed on the beach with the dead man. The lifeguards made a report and called the Military Police (PM). Corporal Espedito Dias Romão, a tall, strong Black man, was in charge of the Bertioga police station that afternoon. It is ironic that he was precisely the authority to record the death of Mengele, who had said he was terrified of Black people and used to declare that “slavery should never have ended.”7

Arriving at the beach, Corporal Dias Romão found Liselotte nervous. She told him that her uncle had died. The policeman asked for the dead man’s documents, but they were at the beach house. She walked there and returned with a foreigner’s ID card, which listed the name Wolfgang Gerhard, born in Leibnitz, Austria, on September 3, 1925. The document was of a fifty-three-year-old man. The age of the body lying on the beach was in fact sixty-seven, a fourteen-year difference that the young policeman didn’t notice. When he received the document, he filed the police report without suspecting anything. The only thing that caught his eye was the nationality: Austrian.8 Liselotte gave the address of her own house in São Paulo, as if the uncle had lived with her. Corporal Dias, who until then hadn’t heard much about Nazism or the Holocaust, simply wrote down the details, which he then passed on to the police and the fire department. For him, it was just a bureaucratic procedure to report an accident, which he described as a “sudden illness followed by drowning.” The police officer requested an official vehicle to take the body to the Forensic Medical Institute in Guarujá. While the transport had not yet arrived, the deceased remained lying on the sand, half-naked, wearing nothing but shorts. A woman appeared with a candle and lit it next to the dead man. The mothers who were still on the beach took the children away so they wouldn’t see the scene. It was late afternoon, and the vehicle was taking its time.

Corporal Dias Romão stayed with Liselotte. She kept her head down almost the whole time, never looking away from her friend. She spoke to the policeman as little as possible. To those observing the scene, it seemed like the normal behavior of a person who had just lost someone close to them. In Liselotte’s case, however, it wasn’t only sadness that dominated her thoughts; many practical issues were at stake. She needed to think quickly about what she was going to do. The fact that her children had gone to sleep at the house of a neighbor she hardly knew and that her husband was in the hospital worried her. And not only that: she knew the body next to her belonged to one of the world’s most wanted war criminals. Would she now reveal the identity of the man she had helped to hide for so long? What would the consequences be for her and her children? She had to deal with all these questions and doubts on her own, without raising suspicion.

The first decision was to stick to the version that the dead man was Wolfgang Gerhard, as stated in the ID card. Even if she decided to reveal the truth, she wouldn’t be able to prove what she was saying, because the name and the information on the document were authentic. Only the photo was false. Wolfgang’s original photo had been carefully removed and in its place was a wallet-sized picture of Mengele, by then an old man with a large moustache. His real name was already well known, and he couldn’t appear on an identity card without attracting attention. As far as Brazilian official documentation, neither Josef Mengele nor Uncle Peter existed; only Wolfgang Gerhard, the Austrian friend who had actually introduced the old Nazi to the Bossert family. Before returning to Austria, he gave away all the documents he had obtained while in Brazil. He figured that he would no longer need them in Europe, and that they would be very useful to help Mengele remain in the shadows without being discovered. Faced with this mess, Liselotte decided to be practical. She wanted to get it over with and chose to “follow the normal course of events,” as she told the Federal Police years later.9

It was already dawn when the technicians began analyzing the corpse at the Forensic Medical Institute. The doctor on duty, Jaime Edson Andrade de Mendonça, found that the cause of death was “asphyxiation due to submersion in water,” that is, drowning. He didn’t think it was necessary to perform an autopsy or question the identity or age of the dead man. For a coroner, fourteen years don’t make much difference when examining a body within that age range. What matters is the body’s state of conservation; in other words, how well the deceased had taken care of their health during their lifetime. Furthermore, water makes the tissues wrinkle, another reason for the age difference to go unnoticed. Dr. Jaime made no reference to any of this. He just trusted the identification presented by Liselotte and signed the death certificate.

Exhausted, the middle-aged woman took care of every detail, as if it were someone from her family who had died. She found some clothes to dress the dead man: pants, belt, shirt, shoes, and socks. She insisted that the funeral assistant should leave the deceased’s arms alongside the body. This was a request that Mengele himself had made to her. He said that he felt like a soldier, and his last wish was to be laid to rest as if standing at attention. A strange request, since the custom in Brazil was to bury the dead with their hands folded across their chests. The official was discreet and agreed to fulfill her request without questioning it.10

However, one question remained: What would be the body’s final destination? With no one to talk to, Liselotte initially thought of cremating it. It would be convenient, because it would put an end to any trace that might reveal the deceased’s true identity. But it wasn’t possible, because a close relative would have to authorize the procedure. She then remembered that the real Wolfgang Gerhard had instructed her and her husband to have the uncle buried in Embu, on the outskirts of São Paulo, if he died in Brazil. Wolfgang had bought a grave for his mother in the Rosário Cemetery, where many Germans were buried, and there was still space in the burial plot. He wouldn’t use the grave himself, because he was going back to Austria. In addition to leaving his documents for Mengele, Wolfgang also wanted to ensure his burial, because he had always felt responsible for taking care of his friend. Liselotte remembered this and had no doubt that this would be the best destination for Mengele.

The next morning, the body was released. A woman who worked at the funeral home picked up the coffin to take it to the cemetery, which was more than sixty miles away. Liselotte went along, and although it was summer, she was wearing a dark corduroy blouse. During the journey, she complained about the road, which had some impassable stretches.11 When they finally arrived at the Rosário Cemetery, Liselotte went to the administrator and asked about the grave bought by Wolfgang Gerhard.

Gino Carita, an affectionate Italian immigrant, indicated the grave’s location and asked to see the death certificate. When he read that the deceased was Gerhard himself, he wanted to open the coffin to say goodbye. Gino had met the Austrian a few years earlier when he was hired to build a small wall and make a bronze plaque with the birth and death dates of Gerhard’s mother, Friederika. The Austrian returned a few times to visit the tomb and, on the last occasion, he told the administrator that he was going on a trip, but he didn’t say where, and was never seen again. Before leaving, he told him that “an older relative” might be buried next to his mother. Gino couldn’t believe that Wolf, as he called him, was now returning in a coffin. The Italian tried to open it, and Liselotte immediately faked a hysterical attack. She started crying and said that he couldn’t do that, because the man had drowned and was disfigured. This was the only way she could stop him. If he had opened the coffin, the administrator would have immediately noticed the wrong man inside, and she would have been in trouble. After the minor commotion, two gravediggers dug the grave. From what one of them remembers of that day, only Liselotte accompanied the burial. Once the quick, simple, solitary act was over, she could finally go home and see her children again. Most importantly, the secret she had kept for ten years was now buried in Wolfgang Gerhard’s grave.

Liselotte was sure she was doing the right thing. She didn’t think her children would be able to bear the weight that would fall on the shoulders of all the family members if Uncle Peter’s identity was revealed. “Keeping quiet is always better,” she thought. As a Catholic, she believed that God would always help her because, in her mind, her only crime had been to help a friend whom she saw as a scientist, and not as a degenerate doctor who sent thousands to their deaths in the gas chambers of Auschwitz and who tortured innocent women and children with his experiments, without showing any remorse. Instead, the murderer died enjoying himself on the beach one summer afternoon, without ever being tried for the crimes he had committed.

____________

1 “Son may have gone to Bertioga.” O Estado de S. Paulo, June 8, 1985, p. 15.

2 “The exhumation of the enigma.” Veja, June 12, 1985.

3 Personal interview with Liselotte Bossert, November 2017.

4 Interview with a German descendant who spent her summers in Bertioga and witnessed Mengele’s drowning on Enseada Beach. She did not want to be identified for fear of reprisals.

5 Andreas Bossert’s statement to the Federal Police (PF).

6 Statement by Walter Silva, lifeguard in Bertioga, to the police.

7 “Before death, depression.” O Estado de S. Paulo, June 11, 1985.

8 Personal interview with Espedito Dias Romão, held on January 27, 2018.

9 Liselotte Bossert’s statement to the Federal Police.

10 Id.

11 Maria Helena Costa Guerra, an employee of Funerária Nova (or Noa, according to the investigation), testified to the police.

1

INVESTIGATING A DANGEROUS CASE

One of my earliest childhood memories is of a teacher I had. She wasn’t just any teacher, even if she looked like many others. “Tante” Liselotte had European features, was slim, and wore her hair curled in a perm, like most women in the 1980s. None of the schoolkids called her “aunt,” as young schoolchildren commonly do in Brazil; only “Tante,” its German equivalent. It was one of the customs of that school, a Germanic island in the heart of Santo Amaro, in São Paulo. She spoke to us kids in a mixture of Portuguese and German, which felt very familiar to me because that’s how we talked at home. On cold mornings, my mother would send me to class wearing pajama pants under my clothes. As the sun rose and the fun and games made me feel warmer, it was Tante Liselotte who removed my excess layers of clothes. I remember that, whenever I didn’t want to take part in an activity, I hid under her desk in our classroom. The room had huge windows through which we could see a garden. I have many other memories of those years: how we used to run freely through the grass; the little red flowers, said to hold honey inside, that I liked to squeeze; the low wooden gate and pink azalea bushes separating us from the rest of the school and the “big” students. I felt safe in that small universe.

One day, however, things changed. Someone told us that Tante Liselotte would no longer come to teach. There was no farewell. It was a sudden disruption in the middle of the semester. Another woman, I don’t remember exactly who she was, would replace Tante Liselotte, and that was it. I was only six years old, and I was shocked to lose my teacher all of a sudden. Why wouldn’t she come any longer? What had happened? I sensed that the adult buzz surrounding the topic had an air of seriousness about it. I didn’t know exactly what it was, but from my perspective as a child I understood that something was wrong.

Only when I was an adult did I learn that Tante Liselotte, to whom our parents entrusted us every morning, had given protection to the most wanted Nazi criminal in the world at that time, Josef Mengele. For a full ten years, my teacher had hosted the fugitive in her own home in the Brooklin neighborhood, not far from the school in the South Zone of São Paulo. On weekends, she would travel on vacation with him and her family to a farm in Itapecerica da Serra and to the beach in Bertioga. She once even took him to the school gate during a “Festa Junina,” the typical Brazilian festivity in the month of June, without anyone suspecting the identity of that old Nazi, dressed in a beautiful European-style overcoat and felt hat. Liselotte introduced him to the principal as a family friend, a gesture that did not raise suspicion in a school that brought together many members of the German community. Practically everyone had a relative from Germany, Austria, or Switzerland. Liselotte was also the one who buried Mengele under a false name in the Embu cemetery in 1979, so that no one would discover his identity even after his death. Thus she foiled the authorities, the Nazi hunters, and the victims who were seeking justice.

For more than six years, Liselotte had thought these events were behind her, literally buried. She went about her routine, teaching small children at the German school. However, in June 1985, the secret was unexpectedly revealed and her life was turned upside down. Our teacher not only had to leave the school abruptly, but she also became disliked in the community, received anonymous threats over the phone, and had to go several times to the Federal Police Superintendence to give statements. She was indicted for three crimes: hiding a fugitive, making a false statement in a public document, and using a false document. At least eighteen of the thirty-four years that Mengele lived in hiding following the end of World War II, he spent in Brazil, the last ten under protection of Liselotte and her husband.

During all that time she never thought seriously about handing him over to the police. Of course, if she confessed that to the Federal Police, she would have problems with the courts. Therefore, she preferred to play the victim and say that she had been afraid to tell the authorities about Mengele’s presence in Brazil because of threats she had received. People linked to the Nazi doctor allegedly had told her that she shouldn’t open her mouth if she wanted to protect her children. This may well be true, but it wasn’t the full story. In her heart, Liselotte believed she had done nothing wrong by taking in a Nazi criminal who was wanted everywhere. In her reasoning (and in her own words), she wanted to “wholeheartedly” help a person “in trouble,” a friend.

However, Mengele was certainly not a mere “friend.” He was a fugitive from German justice and responsible for countless murders, according to the arrest warrant issued by the Frankfurt Court of Justice. It is true that Mengele had entered Liselotte’s life under a false name, so initially she had had no way of knowing who he was. By the time she discovered his true identity, it was too late: they had become friends, and her whole family was attached to him. The bombshell revelation that the man was actually a war criminal did not damage their relationship; quite the opposite. Liselotte remained faithful to her friend until the end.

Her husband, Wolfram, told police that Mengele knew he was being sought all over the world for the crimes he had committed between May 1943 and January 1945, a period of almost a year and eight months in which he was a medical doctor at the Auschwitz concentration camp. However, contrary to what many people think, he was never the chief doctor of that huge extermination complex. That position belonged to Dr. Eduard Wirths, who was responsible for all the medical activities in the largest Nazi concentration camp. The complex was so large that it was divided into three sub-camps: Auschwitz I (the main camp, or Stammlager), Auschwitz II (Birkenau), and Auschwitz III (Monowitz). Dr. Mengele began by taking charge of the “gypsy camp.”12 When the entire Roma block was exterminated, with almost three thousand men, women, and children sent to the gas chambers, he was promoted to chief doctor of Birkenau.

One of Mengele’s main duties as a “Lagerarzt,” or a concentration-camp doctor, was to select the prisoners who were to die in the gas chambers and those who could still be put to work. This task was called “selection” and ran completely counter to the basic premise of the medical profession, which is to save lives, not to take them. Hermann Langbein, an Austrian prisoner who worked as Dr. Wirths’s secretary, noticed that this complete inversion of values caused conflicts of conscience in some doctors, especially those who took their training seriously and weren’t ardent supporters of Nazism. This was definitely not the case with Mengele. He showed up for work even on his days off and had no remorse about sending helpless people to the gas chambers. His main aim was to find twins, people with dwarfism, and people with other rare conditions, to use them as human guinea pigs in his experiments. Perhaps because of his constant participation in the selections, Mengele was nicknamed the “Angel of Death.” When he appeared in the prisoners’ barracks, everyone trembled with fear because they knew what his presence meant: someone would be chosen to die.

More than the selections and the striking nickname, it was the disclosure of the perverse experiments on human beings that made Mengele known all over the world. These remained unknown to the outside world until the 1960s, after some of the doctor’s surviving victims testified in public at two famous trials: that of Nazi Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, and in the so-called “Auschwitz trials” in Frankfurt. From then on, Mengele’s experiences became better known, and in the popular imagination emerged the image of a pseudoscientist, capable of doing anything to improve the “Aryan race” so it would dominate the world.

This image has appeared in various ways in American culture. Mengele became a fictional character in Ira Levin’s 1976 book, The Boys from Brazil. Two years later, the book was adapted into a movie of the same name, which received three Oscar nominations and featured a star cast: Gregory Peck played the character Josef Mengele, and Laurence Olivier a Nazi hunter. Later, in 1986, the American thrash metal band Slayer turned the “Angel of Death” into the lyrics of one of their songs. Decades after the liberation of Auschwitz, Mengele went from an executioner to a sinister symbol in popular culture.

Contrary to fiction and general belief, Mengele was not a crazy, solitary pseudoscientist. In reality, he had the backing of a leading research institution with enormous prestige in the Third Reich: the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin. There he sent samples of blood and organs taken from Auschwitz prisoners, including children. The young doctor’s great dream was to build a research empire and have a brilliant career after the war. Determined to achieve his goal, he took full advantage of the freedom he had in the concentration camp to commit atrocities in the name of science, protected by the racist and anti-Semitic ideology of Nazism and the idea that all prisoners were going to die sooner or later anyway. For Mengele, Auschwitz was a great deposit of human material to be used in his private research.

The list of topics he wanted to investigate was extremely long: growth disorders (such as dwarfism), methods of sterilization, bone-marrow transplants, typhus, malaria, noma (a disease that mainly affects malnourished children), body abnormalities (such as hunchback and congenital clubfoot), and heterochromia (a condition in which the color of the iris in one eye differs from that in the other). Not to mention research on twins, which had been on the rise since the 1920s. It seems difficult that a single scientist would ever become an expert on such a wide variety of subjects. As the German historian Carola Sachse wrote, it was the scientifically senseless orgy of an excessively arrogant person. As if the various lines of research were not enough, he also collected Jewish skeletons, human embryos, and bodies of dead newborn babies.

The stories of Mengele’s cruel and bizarre experiments have always haunted me, even more so knowing that, when hiding from justice, he received protection from my childhood teacher. For years I was intrigued by what he had done and, most importantly, why. What was behind so much evil? I remember seeing long reports on the Sunday TV shows that talked about human experiments. They were always shocking. It was also shocking that such a man had moved around so freely and lived with impunity in places so close to where I live, and that a teacher of mine had such an intimate connection to him. I’ve always wondered why Tante Liselotte had protected him and what had moved her to do it.

There are several volumes on Mengele published in Europe and the United States, but no in-depth book about him has been written in Brazil, the place where he spent the most time in hiding. As a journalist for over twenty years, I thought it was time to get to the bottom of this story. I began to unravel Mengele’s life through foreign books, and then by searching for documents and people who were close to him. Without a doubt, Tante Liselotte was a key character in this whole story. She was the person best able to tell me what had happened during the years Mengele was hiding in Brazil. But where could I find her, more than thirty years after she left the school? On the internet, her name appeared in several articles from 1985, the year Mengele’s skeleton was found in the Embu cemetery and the case became a worldwide scandal, having received more coverage in the foreign press than the death of Brazil’s President Tancredo Neves two months earlier. After that, there was nothing else. She had disappeared.

I decided to look for the school’s old staff who had known her. A former teacher, who was usually very helpful and sweet to me, didn’t even reply to my message, probably because she realized what I wanted to discuss. I couldn’t find any information about Tante Liselotte, and I didn’t even know if she was still alive. I got in touch with the then-principal of the German school, and we sat down for a chat. “As far as I know, she’s still alive, yes. I saw Liselotte maybe three or four times at the São Paulo City Council. She usually appears at the special session in honor of German-speaking immigrants,” he said. It seemed that the only way to talk to her was to go to her house.

The address where Liselotte lived at the time of the Mengele case was available in various places: magazines, newspapers, official documents, and even foreign books. It remained to be seen whether it was still the same. I decided to go there. I arrived at her house on a Sunday, just before eleven in the morning. A car was parked in front of the gate. From the sidewalk, I could see through the window someone in the living room reading the newspaper. I rang the doorbell. The person on the sofa didn’t even move. I was about to ring again when a woman appeared at the second-floor window. My God, it was her!

It was like seeing a fictional character in the flesh. I began by introducing myself as a former student and current journalist. She asked me what I wanted. I said I would tell her if she came down to the gate, where I was. She resisted my request for a bit but eventually gave in. Certainly, being called “Tante Liselotte” made her curious, or perhaps flattered. Downstairs, she smiled and held out her hand. Her fingers were a little crooked, revealing her advanced age. We stood facing each other, with a waist-height gate between us. I explained that I wanted to write a book about Mengele. She said she didn’t talk about it with anyone, not even her own children.

“I’ve been offered a lot of money to do interviews, but I won’t,” she said with conviction.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because there’s no point. Some believe it all happened one way, others don’t,” she replied. We continued talking about trivialities.

Suddenly, Liselotte let out a somewhat confusing confession: “They often think that everything comes out with age. It doesn’t. Everything is just right.” She finished the sentence without explaining what she meant, laughed, and continued speaking with her heavy accent and a Portuguese that was, at times, rather poor. “Look, it’s like this, we agreed that if I stayed quiet, the Jews will leave me alone. So I stayed quiet. Because I had a family, so I don’t talk about this subject,” she said.

“But what Jews said that to you?” I asked.

Silence. Then: “It was Menachem Russak. He was the Nazijäger, the ‘Nazi hunter.’”

Menachem Russak really existed and was in São Paulo at the time when Mengele’s remains were exhumed. He was the head of the special Israeli unit in charge of hunting down Nazi war criminals.

After a short pause, she mentioned another unintelligible name, saying she was referring to a consul. “What consul would that be?” I thought.

“Did they ever threaten you?” I asked.

“No, they wouldn’t do that. How can you say something like that? You shouldn’t,” she replied in a mocking and ironic tone. I asked if she had ever regretted helping her “friend,” taking care never to mention Mengele’s name directly, because I sensed that it was a kind of taboo for her.

“That’s something else, because I have two children, right?” she replied.

“But what does regret have to do with your children?” I tried to understand.

“Do you know the Gesetze of the Talmud?” she asked me, once again mixing Portuguese and German. “According to the Talmud, they will chase you down to the seventh child in the family. I’m not afraid, but I can’t,” she added. Liselotte did not explain what she meant.

In the Talmud, the collection of Jewish books that record the discussions of the rabbis and are the main source for Jewish law, there is a quote about revenge in the seventh generation. It refers to an interpretation of Genesis in the Bible: the punishment for Cain’s crime comes in the seventh generation, through his descendant Lamech, who murders him. Did Liselotte believe that she would be punished in future generations?

The conversation became more and more mysterious. My childhood teacher was scaring me. The street was empty. The person on the sofa was still there. Who could it be? Liselotte had said she wouldn’t talk about the Mengele case, but all the same kept telling me some strange things. Many answers to my questions were limited to a shake of the head or a sinister smile. Then, by leaps and bounds, the conversation unfolded. Suddenly she asked: “Do you want to know something?”

“I do,” I replied fearfully.

“Just from friend to friend, leave the case.” My eyes widened. Why was she saying that? Was it a threat? “It’s better for you,” she continued. “There’s a lot, a lot that nobody knows yet. I know,” she said and laughed.

“Then you have to tell me,” I insisted.

“No,” she replied seriously. “Nothing at all, because the deal I have with them is serious. When someone says to you ‘look, you’ve got children . . .’”

She let her words hang in the air, implying that she had been seriously threatened by the men she had mentioned earlier.

Another long silence fell between us. I grew more afraid. What was she getting at? Was she threatening me? “You’d better keep quiet about this. It’s a lot of money. A lot of money,” she repeated enigmatically. I was stunned and had no answers. Despite the intimidating atmosphere, we continued talking. She asked if I had a husband or children. I tried to make it seem like normal questions from an old acquaintance, but I immediately felt I was being scrutinized. I was getting more and more tense. She made veiled and direct threats, one after the other: “Look for something else that is not so dangerous to investigate. Because this case is dangerous, believe me,” she said.

“But who do you think could put me in danger?” I asked, playing dumb.

Again, silence. “I’m not going to talk,” she said.

I was stunned. I tried to act normal. I asked one last, light, trivial question to try to clear the air: “Do you miss school?”

She replied, “I don’t miss it. But I’m happy with my life. There are a lot of people who hate me, but what am I going to do? I’m sure I didn’t do anything wrong, that’s all.”

I wished her a good Sunday and said I’d let her know when my book was published. I walked off, turned the corner, and, once out of her sight, picked up my pace.

At that moment, I felt sure that I never wanted to talk about it again. I was afraid. When I got home, I told my sisters about the threats I had received. They laughed at me for fearing a ninety-year-old woman. I tried to remain calm, and replied only, “A ninety-year-old woman who was able to harbor Josef Mengele. I wonder who she’s connected to.” After asking myself this question many times, I came to the conclusion that nobody survives for more than three decades being hunted by the Mossad, the Israeli intelligence service, with an arrest warrant from the German government, and half a dozen Nazi hunters on their trail, unless they have a very well-connected network.

This network wasn’t a grandiose organization like Odessa, the mythical organization to protect SS officers after the Second World War. Its existence has never been proven, and Wolfram himself said that he never received support from any Nazi group. What Mengele found in Brazil, especially in the state of São Paulo, was a network of loyal supporters, European immigrants who, in one way or another, had their lives intertwined with his. In Brazil, Mengele created his “Tropical Bavaria”: a place where he could speak German and maintain his customs, beliefs, friends, and his connection to his homeland. And the best thing: in a climate that was more pleasant than Germany’s. He may have felt “in trouble,” as Liselotte said, but he never came close to facing the punishment deserved by those who commit war crimes and crimes against humanity.

____________

12 The word “gypsy” is today considered pejorative and no longer acceptable in English to describe Roma and Sinti peoples. In this book, the word will only be employed within quotation marks in expressions normally used in historical situations here discussed, such as the “gypsy camp” in Auschwitz (Zigeunerlager).

2

REUNITING MENGELE’S TWINS

JERUSALEM. OCTOBER 1984

Josef Mengele had already been dead and buried for more than five years, but nobody knew that. Or rather, very few people were aware of it: only his friends in Brazil and his relatives in Germany, who helped him live in hiding after World War II. While the dead man had already become a pile of bones in the remote and unsuspected Embu cemetery, victims and hunters of the Nazi doctor naïvely continued the search for a living criminal. Mengele’s whereabouts were a great mystery that fueled the most absurd conspiracy theories. The main suspicion was that he was living in Paraguay. There were also those who claimed to have seen him in the Bahamas, Patagonia, and Uruguay. The famous Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal guaranteed, with strange accuracy, that the former SS captain was at a military base in the tiny Paraguayan town of Laureles, where even the local police were not allowed to enter. Tuviah Friedman, another Nazi hunter, claimed that Mengele was the personal physician of Paraguayan dictator Alfredo Stroessner.13 How they reached such certainties, we don’t know. The fact is that, judging from the totally wrong guesses that reached the press, it was clear that no one had the slightest idea where Mengele was, apart from his close and loyal circle of protectors.

Even without any concrete leads, one woman was determined to find him. Eva Mozes Kor, fifty-one, a Romanian who was born in Transylvania and lived in the United States, dreamed of bringing to justice the man who had used her as a guinea pig when she was a child. “We need to find Mengele before he dies in his own bed,” she said in her heavy accent during a press conference in Jerusalem in October 1984. Mozes Kor had just created the association Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors (CANDLES), which represented the surviving twins of Mengele’s experiments. As well as being the founder, she was the spokesperson for the newly created institution. She gathered journalists to announce that some survivors would be taking a two-mile walk around Auschwitz on January 27 of the following year to mark forty years since the liberation of the camp. It was to be just one event in a much larger campaign: to draw the world’s attention to finding Mengele. The statement that the CANDLES association released to the press contained a frightening fact: three thousand twins had been used by Mengele in medical experiments at Auschwitz and, of that total, only 183 made it out alive. “The criminal who did this to us is still at large,” she said. “Unless we do something about it, nothing will happen,” she added.

Eva was convinced that the more publicity her cause attracted, the better it would be. And she was thinking big. She sent telegrams to President Ronald Reagan of the United States, and President Konstantin Tchernenko of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), inviting the leaders of the two greatest powers of the time to take part in the symbolic march she was organizing.14

Deep down, even more than bringing Mengele to trial, Mozes Kor wanted to find out what substances he had injected into her and her twin sister, Miriam Mozes Zeiger, when they were children. Four decades after the experiments, she still had health problems caused by those injections, but she preferred not to talk about it.15 She was more worried about her sister. Because of the experiments in Auschwitz, Miriam had developed serious kidney infections that didn’t respond to antibiotics. The doctors found that her organs were atrophied, the size of those of a ten-year-old girl, the exact age the sisters had been when they served as guinea pigs in the Nazi laboratory. Unsatisfied, the doctors who analyzed Miriam begged for her files from the concentration camp to try to find out what could have caused it and, perhaps, cure her. The sisters never found either any documents or any person who could explain what had happened to them in that laboratory.

Twins Eva Mozes Kor and Miriam Mozes in Romania.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem.

Miriam lived in Israel and Eva in the US state of Indiana, where she married, had two children, and made a career as a real estate agent. For a long time, Eva couldn’t talk to anyone about her terrible experiences. Her neighbors thought she was strange, and her “weirdness” was the subject of jokes in the neighborhood ever since she chased away a bunch of kids who went trick-or-treating outside her house on Halloween. What seemed like an innocent prank reminded her of the groups of Nazi youths who used to terrorize the Jews in Porț, Romania, when she was a little girl.16

Eva’s relationship with the past only began to change when she watched a TV series titled Holocaust in 1978, more than thirty years after leaving Auschwitz. The show was a resounding success, with 120 million viewers in the United States and the then-newcomer Meryl Streep in the cast. The miniseries touched on a subject that was little discussed in public at the time: the mass murder of Jews in Europe. In four episodes, Holocaust told the story of a Jewish family from Berlin—the Weisses—who had been prosperous and happy until the rise of Nazism, when they lost their rights due to the anti-Semitic policies of the Third Reich and ended up persecuted and destroyed. Many survivors didn’t like the series because they thought the plot oversimplified very complex issues, saying it was a soap opera dealing with a serious topic. Despite the criticism, the miniseries had the merit of giving a face and a name to the suffering of the Jews and raising awareness among the general public, not only in the United States but in Germany, where the series was also a success.

The word “holocaust,” which until then had only been used in restricted circles, gained popularity. The first known use of the term “holocaust” dates back to the thirteenth century. It comes from the Greek word holokauston, which in turn is a translation of the Hebrew word olah. In biblical times, olah was an offering that had to be completely consumed by fire. The use of the term holocaust, therefore, has a religious meaning, which is that murdered Jews, whose bodies were burned entirely in crematoria, are considered a sacrifice to God. Over time, the word began to refer to large-scale murder or destruction.17 Even today, there is a debate about the use of the term “holocaust.” No universal agreement has been reached on its meaning: for example, whether it refers exclusively to the extermination of Jews or whether it can also be used in relation to the massacre of other peoples.18 In Israel, there is a preference for the word “Shoah,” which means “catastrophe” in Hebrew.

After the series’s success, Eva realized that many people began to understand why she was different. Some people even apologized for the way they had treated her before. It was a turning point in her life, in the lives of other survivors, and also in American culture. From then on, the Holocaust gained prominence in popular books and films, such as the bestseller Sophie’s Choice, and the 1982 movie also starring Meryl Streep, who this time won an Oscar for Best Actress. At the same time, there was a race to record in detail the accounts of concentration-camp survivors, a period that was later called the “Era of the Witness.” To preserve these records, public and private archives were created in various countries.19

Eva, who until then hadn’t touched on the subject, became a lecturer, and audiences asked her details about the Nazis’ medical experiments. The problem was that she didn’t know how to answer many of the questions. She then remembered that when Auschwitz had been liberated by the Red Army, she and her sister hadn’t left that hell on their own; other children had left with them. These other liberated twins could provide some useful clues, so she decided to try to find her former childhood companions who appeared in the photos and videos made by the Soviets. It was a difficult task: they were of different nationalities, spoke different languages, and were scattered all over the world. Contacting them at a time when there was no internet, let alone social networks, required Herculean willpower. Eva had had this strength since she was a child. What motivated her in this search was the thought that she could better understand what had happened to her and her sister if she collected the accounts of everyone who had gone through the same experience as them. It was a way of trying to put the pieces of that meaningless puzzle together. Eva and Miriam managed to locate 122 surviving twins from Mengele’s experiments in ten different countries on four continents.20

In January 1985, they held the association’s first international event. The American and Soviet presidents did not attend, which was to be expected. However, Eva and Miriam were firm in their resolve. They managed to take four more twins on the symbolic march to mark the fortieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. It was a small step in spreading the word about the cause. From Poland, the group traveled to Jerusalem.21 It was there that the biggest event of the campaign to draw worldwide attention to the Mengele case was scheduled to take place. CANDLES managed to bring together eighty twins, as well as people with dwarfism, and other witnesses who could talk about the Nazi doctor’s crimes. It wasn’t going to be a real trial because, to that date, no government had managed to arrest Mengele, even though he was one of the world’s most wanted war criminals. The lack of legal backing was not an impediment to Eva and Miriam’s endeavor. Mengele would be “tried” in absentia, at a public hearing. And if that event had no legal value, at least it would serve to spread the word about the crimes he had committed.

Eva Mozes Kor and Miriam Mozes Zeiger. Picture taken in Auschwitz at the same place that the liberation picture was taken [in 1945]. December 1991.

Indiana Historical Society, M1492.

____________

13 “Mystery, myth. Where is Mengele?” O Estado de S. Paulo, March 10, 1985.

14 Survivors Appeal for Information on Nazi Fugitive (UPI), on October 13, 1984.

15 Interview with Eva Mozes Kor by email, conducted on August 1, 2017.

16 Eva Mozes Kor and Lisa Rojany Buccieri, Surviving theAngel of Death: The True Story of a Mengele Twin inAuschwitz. Vancouver: Tanglewood, 2009.

17 “Holocaust,” in Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Available at: <www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/holocaust>. Accessed on: June 3, 2020; “What Is the Origin of the Term Holocaust?” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Available at: <www.britannica.com/story/what-is-the-origin-of-the-term-holocaust>. Accessed on: June 3, 2020.

18 Laurence Rees, The Holocaust: A New History. London: Penguin, 2017.

19 Frank McDonough and John Cochrane, The Holocaust. London: Bloomsbury, 2008, p. 91; “The power of series against institutionalized violence.” Folha de S.Paulo, July 21, 2019.

20 Eva Mozes Kor and Lisa Rojany Buccieri, op. cit., p. 130.

21 “Read about Eva’s road to Forgiveness.” CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center. Available at: <candlesholocaustmuseum.org/our-survivors/eva-kor/her-story/her-story.html/title/read-about-eva-s-road-to-forgiveness>. Accessed on: June 8, 2020.

3

IN SEARCH OF JUSTICE

FEBRUARY 1985

The place chosen for the hearing was symbolic: Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. The name of the event, “J’Accuse” (I accuse), was also symbolic. It was a reference to the famous letter that writer Émile Zola published in the French press in 1898, addressed to the president of France, in which he defended Alfred Dreyfus. That Jewish officer had been unjustly sentenced to life imprisonment on the inhospitable Devil’s Island in French Guiana. The crime attributed to Dreyfus was being a German agent and spying on the French Army, accusations that were later proven false. The campaign launched by Zola to prove the Jewish officer’s innocence exposed the anti-Semitic motivations behind the accusation of espionage. The Dreyfus affair caused quite a stir in the country and became a landmark in the fight against anti-Semitism. The “J’Accuse” of the twentieth century was also part of a campaign to repair an injustice committed against Jewish people: the impunity of Josef Mengele.

The event organizers invited a panel of six renowned experts on Nazi crimes to hear the gruesome stories about the doctor’s work in Auschwitz. Prominent among them was Gideon Hausner, who had been the chief prosecutor in the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel. This case attracted worldwide attention in the 1960s and brought to justice the man who, during World War II, organized and coordinated the deportation of Jews to concentration camps in Eastern Europe.22 Interestingly, Hausner and Mengele were in contact with each other years after the end of the war when both were living in hiding in Buenos Aires.

Another distinguished member of the “J’Accuse” panel was Telford Taylor, who had been the chief US prosecutor at the Nuremberg Military Tribunal during the trials of Nazi collaborators. The presence of Taylor, Hausner, and other important names added credibility and international recognition to the hearing organized by the sisters Eva and Miriam. Thirty witnesses had agreed to testify. For three days, the victims took turns in front of a packed auditorium to talk about their experiences, which were recorded and broadcast worldwide on TV, including in Brazil. Some stories had not been previously told in public and sounded unreal due to the extreme cruelty they revealed.