Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Visit Edo, modern day Tokyo, as experienced by Utagawa Hiroshige in this wonderful tourist guide from the 1850s. Experience Edo as the Japanese loved it, a sophisticated city catering to a wealthy elite of daimyo, local rulers that regularly had to spend time away from their lands, in Edo, where the shogun could keep an eye on them. The 100 Famous Views of Edo was one of the popular print series made in Japan, like Hokusais series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, which had been published earlier in the 1830s and which influenced Hiroshige tremendously (ISBN ES 978-8-411-744-935). But much more important is the influence the 100 Famous Views of Edo had on European impressionists like Van Gogh, Degas, Manet and Monet. Hiroshige impressed with cropped items to create focus and with his horizontal format.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 181

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the authors

Cristina Berna loves photographing and writing. She also creates designs and advice on fashion and styling.

Eric Thomsen has published in science, economics and law, created exhibitions and arranged concerts.

Also by the authors:

World of Cakes

Luxembourg – a piece of cake

Florida Cakes

Catalan Pastis – Catalonian Cakes

Andalucian Delight

World of Art

Hokusai – 36 Views of Mt Fuji

Hiroshige 69 Stations of the Nakasendō

Hiroshige 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō

Hiroshige 100 Famous Views of Edo

Hiroshige Famous Vies of the Sixty-Odd Provinces

Hiroshige 36 Views of Mt Fuji 1852

Hiroshige 36 Views of Mt Fuji 1858

Joaquin Sorolla Landscapes

Joaquin Sorolla Beach

Joaquin Sorolla Boats

Joaquin Sorolla Animals

Joaquin Sorolla Family

Joaquin Sorolla Nudes

Joaquin Sorolla Portraits

Outpets

Deer in Dyrehaven – Outpets in Denmark

Florida Outpets

Birds of Play

Christmas Nativity

Christmas Nativity – Spain

Christmas Nativities Luxembourg Trier

Christmas Nativity United States

Christmas Nativity Hallstatt

Christmas Nativity Salzburg

Christmas Nativity Slovenia

Christmas Markets

Christmas Market Innsbruck

Christmas Market Vienna

Christmas Market Salzburg

Christmas Market Slovenia

and more titles

Missy’s Clan

Missy’s Clan – The Beginning

Missy’s Clan – Christmas

Missy’s Clan – Education

Missy’s Clan – Kittens

Missy’s Clan – Deer Friends

Missy’s Clan – Outpets

Missy’s Clan – Outpet Birds

and more titles

Vehicles

Construction vehicles picture book

Trains

American Fire Engines

American Police Cars

and more titles

Contact the authors

[email protected] Published by www.missysclan.net

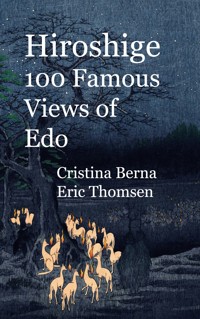

Cover picture: print 118, New Year's Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Ōji

Inside: print 58, Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ohashi Bridge and Atake (Ohashi Atake no Yudachi)

Contents

Introduction

Utagawa Hiroshige

The One Hundred Famous Views of Edo

No 1:

Nihonbashi, Clearing After Snow

No 2:

Kasumigaseki

No 3:

Hibiya and Soto-Sakurada From Yamashita-Cho

No 4:

Tsukudajima From Eitai Bridge

No 5:

Ryogoku Ekoin and Moto-Yanagibashi Bridge

No 6:

Hatsune Riding Grounds, Bakuro-cho

No 7:

Cotton-Goods Lane, Odenma-cho

No 8:

Suruga-cho

No 9:

Yatsukoji, Inside Sujikai Gate

No 10:

Dawn at Kanda Myojin Shrine

No 11:

Kiyomizu Hall and Shinobazu Pond at Ueno

No 12:

Ueno Yamashita

No 13:

Shitaya Hirokoji

No 14:

Temple Gardens, Nippori

No 15:

Suwa Bluff, Nippori

No 16:

Flower Pavilion, Dango Slope, Sendagi

No 17:

View to the North from Asukayama

No 18:

Oji Inari Shrine

No 19:

Dam on the Otonashi River at Oji

No 20:

The Kawaguchi Ferry and Zenkoji Temple

No 21:

Mount Atago, Shiba

No 22:

Furukawa River, Hiroo

No 23:

Chiyogaike Pond, Meguro

No 24:

New Fuji, Meguro

No 25:

Original Fuji, Meguro

No 26:

Armor-Hanging Pine, Hakkeisaka

No 27:

Plum Garden, Kamata (Kamata no Umezono)

No 28:

Gotenyama, Shinagawa

No 29:

Moto-Hachiman Shrine, Sumamura

No 30:

Plum Estate, Kameido

Van Gogh copy

No 31:

Azuma Shrine and the Entwined Camphor

No 32:

Yanagishima

No 33:

Towboats Along the Yotsugi-dori Canal

No 34:

Night View of the Matsuchiyama and Sam'ya Canal (Matsuchiyama San'yabori)

No 35:

Suijin Shrine and Massaki on the Sumida River (Sumidagawa Suijin no Mori Massaki),

No 36:

View From Massaki of Suijin Shrine, Uchigawa Inlet, and Sekiya

No 37:

Tile Kilns and Hashiba Ferry, Sumida River (Sumidagawa Hashiba no Watashi Kawaragawa)

No 38:

Dawn Inside the Yoshiwara

No 39:

Distant View of Kinryuzan Temple and Azuma Bridge (Azumabashi Kinryuzan Enbo)

No 40:

Basho's Hermitage and Camellia Hill on the Kanda Aqueduct at Sekiguchi

No 41:

Ichigaya Hachiman Shrine

No 42:

Blossoms on the Tama River Embankment

No 43:

Nihonbashi Bridge and Edobashi Bridge (Nihonbashi to Edobashi)

No 44:

View of Nihonbashi Tori-itchome (Nihonbashi Tori-itchome Ryakuzu)

No 45:

Yatsumi no hashi (Yatsumi Bridge)

No 46:

Yoroi Ferry, Koami-cho (Yoroi no Watashi Koami-cho)

No 47:

Seido and Kanda River From Shohei Bridge

No 48:

Suido Bridge and Surugadai (Suidobashi Surugadai)

No 49:

Fudo Falls, Oji

No 50:

Kumano Junisha Shrine, Tsunohazu

No 51:

Sanno Festival Procession at Kojimachi l-Chome

No 52:

Akasaka Kiribatake

No 53:

Zojoji Pagoda and Akabane

No 54:

Benkei Moat From Soto-Sakurada to Kojimachi

No 55:

Sumiyoshi Festival, Tsukudajima

No 56:

Mannen Bridge, Fukagawa (Fukagawa Mannenbashi)

No 57:

Mitsumata Wakarenofuchi

No 58:

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake

Van Gogh copy

No 59:

Ryogoku Bridge and the Great Riverbank

No 60:

Asakusa River, Great Riverbank, Miyato River

No 61:

Pine of Success and Oumayagashi, Asakusa River

No 62:

Komakata Hall and Azuma Bridg

e

No 63:

Ayase River and Kanegafuchi

No 64:

Horikiri Iris Garden (Horikiri no Hanashobu)

No 65:

Inside Kameido Tenjin Shrine (KameidoTenjin Keidai

No 66:

Spiral Hall, Five Hundred Rakan Temple

No 67:

Sakasai Ferry

No 68:

Open Garden at Fukagawa Hachiman Shrine

No 69:

Hall of Thirty-Three Bays, Fukagawa

No 70:

Nakagawa River Mouth

No 71:

Scattered Pines, Tone River

No 72:

Haneda Ferry and Benten Shrine (Haneda no Watashi Benten

No 73:

The City Flourishing, Tanabata Festival

No 74:

Silk-Goods Lane, Odenma-cho

No 75:

Dyers' Quarter, Kanda

No 76:

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi Bridge

No 77:

Inari Bridge and Minato Shrine, Teppozu

No 78:

Teppozu and Tsukiji Honganji Temple

No 79:

Shiba Shinmei Shrine and Zojoji Temple

No 80:

Kanasugi Bridge and Shibaura

No 81:

Ushimachi, Takanawa

No 82:

Moon-Viewing Point (Tsuki no Misaki)

No 83:

Shinagawa Susaki

No 84:

Grandpa's Teahouse, Meguro

No 85:

Kinokuni Hill and Distant View of Akasaka Tameike

No 86:

Naito Shinjuku, Yotsuya

No 87:

Benten Shrine, Inokashira Pond

No 88:

Takinogawa, Oji

No 89:

Moon Pine, Ueno

No 90:

Night View of Saruwaka-machi

No 91:

Inside Akiba Shrine, Ukeji

No 92:

Mokuboji Temple, Uchigawa Inlet, Gozensaihata

No 93:

Niijuku Ferry

No 94:

Maple Trees at Mama, Tekona Shrine and Linked Bridge

No 95:

View of Konodai and the Tone River

No 96:

Horie and Nekozane

No 97:

Five Pines, Onagi Canal

No 98:

Fireworks at Ryogoku (Ryogoku Hanabi)

No 99:

Kinryuzan Temple, Asakusa (Asakusa Kinryuzan)

No 100:

Nihon Embankment, Yoshiwara

No 101:

Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival

No 102:

Minowa, Kanasugi, Mikawashima

No 103:

Senju Great Bridge

No 104:

Koume Embankment

No 105:

Oumayagashi

No 106:

Fukagawa Lumberyards

No 107:

Fukagawa Susaki and Jumantsubo

No 108:

View of Shiba Coast

No 109:

Minami-Shinagawa and Samezu Coast

No 110:

Robe-Hanging Pine, Senzoku Pond

No 111:

Meguro Drum Bridge and Sunset Hill

No 112:

Atagoshita and Yabu Lane

No 113:

Aoi Slope, Outside Toranomon Gate

No 114:

Bikuni Bridge in Snow

No 115:

Takata Riding Grounds

No 116:

Sugatami Bridge, Omokage Bridge, and Jariba at Takata

No 117:

Hilltop View, Yushima Tenjin Shrine

No 118:

New Year's Eve Foxfires at the Changing Tree, Ōji

No 119:

View of the Kiribata (Paulownia Imperiales) Trees at Akasaka on a Rainy Evening

Reference

s

Introduction

Visit Edo, modern day Tokyo, as experienced by Utagawa Hiroshige in this wonderful tourist guide from the 1850s.

Experience Edo as the Japanese loved it, a sophisticated city catering to a wealthy elite of daimyō, local rulers that regularly had to spend time away from their lands, in Edo, where the shogun could keep an eye on them.

The 100 Famous Views of Edo was one of the popular print series made in Japan, like Hokusai’s series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, which had been published earlier in the 1830s and which influenced Hiroshige tremendously (ISBN ES 978-8-411-744-935).

But much more important is the influence the 100 Famous Views of Edo had on European impressionists like Van Gogh, Degas, Manet and Monet. Hiroshige impressed with cropped items to create focus and with his horizontal format.

Cristina and Eric

Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige (in Japanese: 歌川 広重), also called Andō Hiroshige (in Japanese: 安藤 広重;), was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition. He was born 1797 and died 12 October 1858.

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as "picture[s] of the floating world".

Hiroshige is best known for his horizontal-format landscape series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, which is the subject of this book, and for his vertical-format landscape series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

The main subjects of his work are considered atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose focus was more on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868).

The Edo period was a period with strong feudal control by the Tokugawa shogunate, with stability and economic growth, very closed to outside influence, although methods were imported and applied and a flowering cultural and artistic life.

The popular series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai (ISBN ES 978-8-411-744-935) was a strong influence on Hiroshige's choice of subject. Hiroshige's approach is ambient, much more detailed,more like photographs, than Hokusai's more poetic and bolder, more formal and focused prints.

Where Hokusai gives you an immediate experience just from looking at his prints, with Hiroshige you have to look more carefully, devote more time, to decipher the details and the meaning.

Subtle use of color was essential in Hiroshige's prints, often printed with multiple impressions in the same area and with extensive use of bokashi (color gradation), both of which were rather labor-intensive techniques.

Thirty-six Views, print 27: Futami Bay in Ise Province, Hiroshige: Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji 1858 ISBN ES 978-8-413-731-148 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:27_-_Futami_Bay.jpg

For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

The Meiji Restoration followed in 1868 after Commodore Matthew C Perry had forced Japan to open its ports to foreign trade in 1863. It meant an end to the shogunate, the feudal ruling system, restored the powers to the emperor who centralized government and industrialization.

Hiroshige's work came to have a marked influence on Western painting towards the close of the 19th century as a part of the trend in Japonism.

Western artists, such as Manet and Monet, collected and closely studied Hiroshige's compositions. Vincent van Gogh even went so far as to paint copies of two of Hiroshige's prints from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

Hiroshige was born in 1797 in the Yayosu Quay section of the Yaesu area in Edo (modern Tokyo). He was of a samurai background, and is the greatgrandson of Tanaka Tokuemon, who held a position of power under the Tsugaru clan in the northern province of Mutsu.

Wind Blown Grass Across the Moon – by Hiroshige https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_Wind_Blown_Grass_Across_the_Moon_-_Utagawa_Hiroshige_(Ando).jpg

Hiroshige studied under Toyohiro of the Utagawa school of artists. Hiroshige's grandfather, Mitsuemon, was an archery instructor who worked under the name Sairyūken.

Returning Sails at Tsukuda, from Eight Views of Edo, Utagawa Toyohiro between 1802 and 1828, Brooklyn Museum online, image: Opencooperhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_Returning_Sails_at_Tsukuda_from_Eight_Views_of_Edo_-_Utagawa_Toyohiro.jpg

Hiroshige's father, Gen'emon, was adopted into the family of Andō Jūemon, whom he succeeded as fire warden for the Yayosu Quay area.

Hiroshige went through several name changes as a youth: Jūemon, Tokubē, and Tetsuzō. He had three sisters, one of whom died when he was three. His mother died in early 1809, and his father followed later in the year, but not before handing his fire warden duties to his twelve-year-old son. He was charged with prevention of fires at Edo Castle, a duty that left him much leisure time.

Not long after his parents' deaths, perhaps at around fourteen, Hiroshige—then named Tokutarō— began painting. He sought the tutelage of Toyokuni of the Utagawa school, but Toyokuni had too many pupils to make room for him. A librarian introduced him instead to Toyohiro of the same school.

By 1812 Hiroshige was permitted to sign his works, which he did under the art name Hiroshige. He also studied the techniques of the well-established Kanō school, the nanga whose tradition began with the Chinese Southern School, and the realistic Shijō school, and likely the perspective techniques of Western art and uki-e.

Hiroshige's apprentice work included book illustrations and single-sheet ukiyo-e prints of female beauties and kabuki actors in the Utagawa style, sometimes signing them Ichiyūsai or, from 1832, Ichiryūsai. In 1823, he resigned his post as fire warden, though he still acted as an alternate. He declined an offer to succeed Toyohiro upon the master's death in 1828.

It was not until 1829–1830 that Hiroshige began to produce the landscapes he has come to be

known for, such as the Eight Views of Ōmi series. He also created an increasing number of bird and flower prints about this time. About 1831, his Ten Famous Places in the Eastern Capital appeared, and seem to bear the influence of Hokusai, whose popular landscape series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji had recently seen publication (ISBN ES 978-8411-744-935).

An invitation to join an official procession to Kyoto in 1832 gave Hiroshige the opportunity to travel along the Tōkaidō route that linked the two capitals. He sketched the scenery along the way, and when he returned to Edo he produced the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, which contains some of his best-known prints. Hiroshige built on the series' success by following it with others, such as the Illustrated Places of Naniwa (1834), Famous Places of Kyoto (1835), another Eight Views of Ōmi (1834). As he had never been west of Kyoto, Hiroshige-based his illustrations of Naniwa (modern Osaka) and Ōmi Province on pictures found in books and paintings.

Hiroshige's first wife helped finance his trips to sketch travel locations, in one instance selling some of her clothing and ornamental combs. She died in October 1838, and Hiroshige remarried to Oyasu, sixteen years his junior, daughter of a farmer named Kaemon from Tōtōmi Province.

Around 1838 Hiroshige produced two series entitled Eight Views of the Edo Environs, each print accompanied by a humorous kyōka poem. The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō saw print between about 1835 and 1842, a joint production with Keisai Eisen, of which Hiroshige's share was forty-six of the seventy prints. Hiroshige produced 118 sheets for the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo over the last decade of his life, beginning about 1848.

Hiroshige lived in the barracks until the age of 43. Gen'emon and his wife died in 1809, when Hiroshige was 12 years old, just a few months after his father had passed the position on to him.

Although his duties as a fire-fighter were light, he never shirked these responsibilities, even after he entered training in Utagawa Toyohiro's studio. He eventually turned his firefighter position over to his brother, Tetsuzo, in 1823, who in turn passed on the duty to Hiroshige's son in 1832.

View of the Whirlpools at Awa triptych, 1857, part of the series "Snow, Moon and Flowers” by Hiroshigehttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Utagawa_Hiroshige._The_swirls_of_the_Naruto_Strait_in_the_province_of_Awa._1857.jpg

Hiroshige II was a young print artist, Chinpei Suzuki, who married Hiroshige's daughter, Otatsu. He was given the artist name of "Shigenobu". Hiroshige intended to make Shigenobu his heir in all matters, and Shigenobu adopted the name "Hiroshige" after his master's death in 1858, and thus today is known as Hiroshige II. However, the marriage to Otatsu was troubled and in 1865 they separated. Otatsu was remarried to another former pupil of Hiroshige, Shigemasa, who appropriated the name of the lineage and today is known as Hiroshige III.

Suō Iwakuni, Hiroshige II, 1859https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hiroshige_II_Su%C5%8D_Iwakuni.jpg

Both Hiroshige II and Hiroshige III worked in a distinctive style based on that of Hiroshige, but neither achieved the level of success and recognition accorded to their master. Other students of Hiroshige I include Utagawa Shigemaru, Utagawa Shigekiyo, and Utagawa Hirokage.

In his declining years, Hiroshige still produced thousands of prints to meet the demand for his works, but few were as good as those of his early and middle periods. He never lived in financial comfort, even in old age. In no small part, his prolific output stemmed from the fact that he was poorly paid per series, although he was still capable of remarkable art when the conditions were right — his great One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景Meisho Edo Hyakkei) was paid for up-front by a wealthy Buddhist priest in love with the daughter of the publisher, Uoya Eikichi (a former fishmonger).

In 1856, Hiroshige "retired from the world," becoming a Buddhist monk; this was the year he began his One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He died aged 62 during the great Edo cholera epidemic of 1858 (whether the epidemic killed him is unknown) and was buried in a Zen Buddhist temple in Asakusa. Just before his death, he left a poem:

Teppōzu Akashi-bashi, Hiroshige III, c. 1870https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hiroshige_III_-_Tepp%C5%8Dzu_Akashi-bashi.jpg

"I leave my brush in the East And set forth on my journey. I shall see the famous places in the Western Land."

(The Western Land in this context refers to the strip of land by the Tōkaidō between Kyoto and Edo, but it does double duty as a reference to the paradise of the Amida Buddha).

Despite his productivity and popularity, Hiroshige was not wealthy—his commissions were less than those of other in-demand artists, amounting to an income of about twice the wages of a day laborer. His will left instructions for the payment of his debts.

Hiroshige produced over 8,000 works. In his early work he largely confined himself to common ukiyo-e themes such as women (美人画bijin-ga) and actors (役者絵yakusha-e).

Then, after the death of Toyohiro, Hiroshige made a dramatic turnabout, with the 1831 landscape series Famous Views of the Eastern Capital (東都名所Tōto Meisho) which was critically acclaimed for its composition and colors.

A dark night printing of the view sometimes dubbed "Man on Horseback Crossing a Bridge." From the series The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, this is View 28 and Station 27 at Nagakubo-shuku, depicting the Wada Bridge across the Yoda River Brooklyn Museum online collection. A brighter example is shown in author´s Hiroshige 53 Stations of the Tokaido Hoeido.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kisokaido27_Nagakubo.jpg

This set is generally distinguished from Hiroshige's many print sets depicting Edo by referring to it as Ichiyūsai Gakki, a title derived from the fact that he signed it as Ichiyūsai Hiroshige. With The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833–1834), his success was assured. These designs were drawn from Hiroshige's actual travels of the full distance of 490 kilometers (300 mi). They included details of date, location, and anecdotes of his fellow travelers, and were immensely popular.

In fact, this series was so popular that he reissued it in three versions, one of which was made jointly with Kunisada. Hiroshige went on to produce more than 2000 different prints of Edo and post stations Tōkaidō, as well as series such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō (1834– 1842) and his own Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (1852–1858). Of his estimated total of 5000 designs, these landscapes comprised the largest proportion of any genre.

He dominated landscape printmaking with his unique brand of intimate, almost small-scale works compared against the older traditions of landscape painting descended from Chinese landscape painters such as Sesshu. The travel prints generally depict travelers along famous routes experiencing the special attractions of various stops along the way.

They travel in the rain, in snow, and during all of the seasons. In 1856, working with the publisher Uoya Eikichi, he created a series of luxury edition prints, made with the finest printing techniques including true gradation of color, the addition of mica to lend a unique iridescent effect, embossing, fabric printing, blind printing, and the use of glue printing (wherein ink is mixed with glue for a glittery effect).

Hiroshige pioneered the use of the vertical format in landscape printing in his series Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces. One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (issued serially between 1856 and 1859) was immensely popular. The set was published posthumously and some prints had not been completed — he had created over 100 on his own, but two were added by Hiroshige II after his death.

Hiroshige was a member of the Utagawa school, along with Kunisada and Kuniyoshi. The Utagawa school comprised dozens of artists, and stood at the forefront of 19th century woodblock prints.

Keisai Eisen was influenced by and worked with Hiroshige. This is his print for station Oiwake, from The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō, 1830s. ISBN ES 978-8-413-730-585.https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Kisokaido20_Oiwake.jpg

Particularly noteworthy for their actor and historical prints, members of the Utagawa school were nonetheless well-versed in all of the popular genres.

During Hiroshige’s time, the print industry was booming, and the consumer audience for prints was growing rapidly. Prior to this time, most print series had been issued in small sets, such as ten or twelve designs per series. Increasingly large series were produced to meet demand, and this trend can be seen in Hiroshige’s work, such as The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.

In terms of style, Hiroshige is especially noted for using unusual vantage points, seasonal allusions, and striking colors. In particular, he worked extensively within the realm of meisho-e (名所絵) pictures of famous places. During the Edo period, tourism was also booming, leading to increased popular interest in travel.