Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Recent years have brought about a crisis of confidence in the historical profession, leading increasing numbers of readers to ask the question: "How can I know that the stories told by a historian are reliable?" Histories and Fallacies is a primer for those seeking guidance through conceptual and methodological problems in the discipline of history. Historian Carl Trueman presents a series of classic historical problems as a way to examine what history is, what it means, and how it can be told and understood. Each chapter in Histories and Fallacies gives an account of a particular problem, examines a classic example of that problem, and then suggests a solution or approach that will bear fruit. Readers who come to understand the question of objectivity through an examination of Holocaust denial or interpretive frameworks through Marxism will not just be learning theory but will already be practicing fruitful approaches to history. Histories and Fallacies guides both readers and writers of history away from dead ends and methodological mistakes, and into a fresh confidence in the productive nature of the historical task.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“This is a very good book, full of historiographical wisdom. I recommend it strongly as a sure and encouraging guide to budding historians befuddled by the so-called ‘history wars,’ and to anyone who is interested in the challenges attending those who represent the history of Christian thought.”

Douglas A. Sweeney, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

“Carl Trueman’s cogent and engaging approach to historiography provides significant examples of problems faced by historians and the kinds of fallacies frequently encountered in historical argumentation. Trueman steers a clear path between problematic and overdrawn conclusions on the one hand and claims of utter objectivity on the other. His illustrations, covering several centuries of Western history, are telling. He offers a combination of careful historical analysis coupled with an understanding of the logical and argumentative pitfalls to which historians are liable that is a service to the field and should provide a useful guide to beginning researchers. A must for courses on research methodology.”

Richard Muller, P. J. Zondervan Professor of Historical Theology, Calvin Theological Seminary

“Because the past shapes the present, a just understanding of the past is important for any individual, society, or church. Here is wise and practical advice for those wanting to write history for others about how to do it well. Follow this guidance and avoid the pitfalls!”

David Bebbington, Professor of History, University of Stirling

Histories and Fallacies: Problems Faced in the Writing of History

Copyright © 2010 by Carl R. Trueman

Published by Crossway

1300 Crescent Street

Wheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided by USA copyright law.

Interior design and typesetting: Lakeside Design Plus

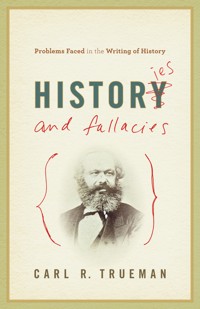

Cover image: Photographic visiting card of Karl Marx (1818–93) with his signature (photo) by French School (19th century) Musee de L’Histoire Vivante, Montreuil, France/ Archives

Charmet/ The Bridgeman Art Library

First printing 2010

Printed in the United States of America

Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-58134-923-8 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-1263-6 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-1264-3 ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-2080-8

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Trueman, Carl R. Histories and fallacies : problems faced in the writing of history / Carl R. Trueman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-58134-923-8 (trade pbk.)—ISBN 978-1-4335-1263-6 (PDF) —ISBN 978-1-4335-1264-3 (Mobipocket)—ISBN 978-1-4335-2080-8 (ePub)

1. Historiography—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. History—Philosophy. 3. History— Methodology. 4. History—Errors, inventions, etc. I. Title.

D13.T74 2010 907.2—dc22

2010021878

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

VP 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1Acknowledgments

11

Introduction

13

1. The Denial of History

25

2. Grand Schemes and Misdemeanors

69

3. The Past Is a Foreign Country

109

4. A Fistful of Fallacies

141

Concluding Historical Postscript

169

Appendix: The Reception of Calvin: Historical Considerations

183

This book is one that I had wanted to write for some time. I have always loved all kinds of history, and so when Allan Fisher offered me the opportunity to write on topics outside of my immediate area of specialization, such as Holocaust Denial and Marxism, the temptation was irresistible. Thanks therefore go to Allan for commissioning the volume; to Justin Taylor for suggesting the idea in the first place; and to all the staff at Crossway who have been both very patient with the constant delays to the book and so efficient in expediting the process once I had finished the manuscript. As always, I am indebted to my colleagues in Academic Affairs at Westminster, Mrs. Becky Lippert and Mrs. Leah Stapleton, who have shouldered much of the administrative burden so that I have been free to pursue my writing projects. Finally, my wife and children have, as always, proved a constant source of encouragement and inspiration.

One reason for the book’s delay was the death of my father in July 2008. The book is dedicated to his memory.

Why write a book on how to do history? This is without a doubt a good question, especially for me. For many years, I looked with withering contempt on those who wrote such books, my philosophy being something like a historian’s version of George Bernard Shaw’s attitude to teachers: those who can write history, do write history; those who cannot, write books telling others how to do it. Yet,after spending much of the last twenty years involved in some form or another in the writing and teaching of history, I have come to the conclusion that there is a place for books that reflect on the nature of the historical task.

To explain this, I need to offer a little autobiographical reflection. For as long as I can remember, I have enjoyed stories. As a child, I was entranced by the epics of ancient mythology—the adventures of Odysseus, the Trojan War, and the antics of pagan gods, be they Egyptian, Greek, or Norse. I also loved the stories contained in the Arabian Nights, the Icelandic sagas, and the various other collections of myths and legends that I found on my father’s bookcase or in the local library. Indeed, some of my earliest memories are of my father reading Dickens’s neglected work, A Child’s History of England, to me as I went to bed at night. I have never lost this love, and still enjoy nothing better than reading this kind of epic material; but as I grew up, I also broadened my tastes to include a much wider taste in literature, from Thomas Hardy to Raymond Chandler. If there was a good story out there, I wanted to read it.

Strange to tell, I came rather late to history, in the last two years of my studies on the Classical Tripos at the University of Cambridge. I had chosen Classics for a number of reasons: I was good at Latin, and had the typical state grammar schoolboy’s attitude of focusing on what I did well and abandoning that which I found boring; and, of course, in studying Classics, I could spend my time reading all those things I enjoyed—the Homeric epics, the tales of gods and heroes, the great myths and legends of the classical world. History was not a motivating factor: at school it had always seemed to be an endless list of names and dates and statistics, with the result that, again as a typical grammar schoolboy, I applied myself minimally to it and did not take it further than the fifth form (that’s age sixteen, for American readers). But at Cambridge, all that changed. The 1980's were a great time to be doing Classics at this university. Under the brilliant lectures of Keith Hopkins and Paul Millet and the breathtaking supervision of Paul Cartledge, I suddenly realized that at the heart of history was the telling of stories that explained the past. There were a variety of such stories—economic, social, cultural, military, etc.—but far from being a dry collection of names, dates, and places, history could possess all the narrative excitement of the epic myths I loved so well; more than that, these stories were attempts to wrestle with the past in a way that tried to explain why things had happened the way they had. Paul Cartledge was particularly impressive. Basically a Marxist historian (who has since gone on not only to hold a chair at Cambridge but also to become something of a “television don,” with a number of acclaimed series, including one on Sparta, to his credit), Dr. Cartledge told the story of ancient Greece from the perspective of class struggle, a perspective to which Athens was not particularly susceptible but which bore great fruit in studies of Sparta, his own chosen area of specialization, whose social organization lent itself to precisely such analysis. Even those who disagree with his approach would have to concede that what he offered was a cogent, coherent account of the ancient Greek world, put forth in the public domain, open for all to see, to agree with, or to criticize.

Since my time at Cambridge, my love for history has known no bounds. I often tell people that I have the greatest job in the world: I am paid to tell stories. The stories I tell happen to relate to the history of the church, but, frankly, I could have studied any aspect of the past and enjoyed doing it. And, in my classes, I spend little time hammering names and dates in the abstract into my students; they can get that from the textbooks I recommend. That’s the purpose of textbooks: to cover the boring material so that the lecturer does not have to, but rather is free to focus on the discipline’s more interesting aspects. I do not teach timelines; I try instead to engage students by showing them how to construct narratives of the past in a way that unlocks that past for an audience in the present.

But this is where key questions for the historian start to come into play. I have said above that I loved the stories in the Greek myths and the Arabian Nights. I have also said that I loved the stories of histories, be they of the kings of ancient Sparta, the emperors of Rome, the French Revolution, or the cataclysms of the twentieth century. But what is the difference? Indeed, is there any difference between, let’s say, Homer’s account of Odysseus’s travels and Richard Evans’s account of the rise of the Third Reich?

Most would probably respond:of course there is. The Third Reich actually happened; the adventures of Odysseus are a myth, at best of tenuous relationship to anything that really occurred in the ancient world. So far, so good; but the last half century has witnessed a veritable earthquake in the field of the historical discipline, which has brought such a simple, straightforward, common-sense answer into serious question. To put the problem succinctly and simply, the question has been raised in various forms as to how we know the stories being told us by historians are reliable. Given the historian’s constructive role in the storytelling and the fact that no story is either identical with the past (a story is, after all, not the events themselves, but words, whether spoken or written) or an exhaustive account of the past (everyone has a perspective, and everyone is selective in what they include and exclude), does not every historical narrative become unavoidably relative compared to any other?

This crisis in confidence in the historical profession can be illustrated with reference to two recent phenomena. The first is a bill introduced to the Florida state legislature in 2006 by the state’s then governor, Jeb Bush, which was intended to have an immediate impact upon the way history is taught. Here is how the matter was reported on one news Web page, starting with a quotation from the text of the bill itself:

“American history shall be viewed as factual, not constructed, shall be viewed as knowable, teachable, and testable, and shall be defined as the creation of a new nation based largely on the universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” To that end teachers are charged not only to focus on the history and content of the Declaration but are also instructed to teach the “history, meaning, significance and effect of the provisions of the Constitution of the United States and the amendments thereto. . . .” Other bill provisions place new emphasis on “flag education, including proper flag display and flag salute”and on the need to teach “the nature and importance of free enterprise to the United States economy.1

The bill as it stands would appear to be an attempt to hit back at that kind of radical relativism which, in its crudest form (and not a form one finds very often) declares that all narratives are equally true and valid, and that the writing of history is really just the projection of individual viewpoints. It is also, of course, arguable that it is an example of precisely the kind of approach to history that the relativists seek to critique: that which intentionally privileges its own position with the status of “just the facts,” and effectively reduces the number of valid accounts of history to its own version, while tarring others with the brush of being political inventions of those out to subvert the status quo. If the narrative is to focus, for example, on “the nature and importance of free enterprise to the United States economy,” it would seem to be a small step indeed between the telling of history and the advocating of a particular economic philosophy, which just happened to be that of the governor of Florida. Further, even if we discount what would seem to be an obvious political agenda behind this pedagogical legislation, can we reduce history just to the parameters set therein? What about the history of art or of literature? What about approaches that focus on economics, or ethnicity, or immigration patterns? Are none of these worth studying? Are there no valid histories that can be built around these things?

In short, the proposed Florida legislation seems to make two basic mistakes: it fails to understand that history is not simply a collation of facts which can only be related together in one valid narrative; and it restricts the number of worthwhile topics of study, and, indeed does so in a way that seems to smuggle the conclusion in to the very premise. Politicians generally make bad academics, of course, so we should not be too hard on the idiotic nature of such statements. Yet, for all of its obvious flaws, the proposed legislation does have at its heart something that is a very valid concern: to rule out of bounds the possibility that there are a potentially infinite number of sometimes contradictory yet equally valid ways of talking about the past. The attempt may be ham-fisted, overblown, and inept, but at heart it is trying to make the point that some accounts of history are more true and more valid than others.

This is where the second example is instructive, that of Holocaust Denial (HD). I want to look at HD in somewhat more detail in chapter 1; for now, it is sufficient to note it as a phenomenon. There is an old adage among historians that no event in history is so certain that, sooner or later, somebody won’t come along and deny that it ever happened. One can think of numerous examples. Take, for example, the death of Elvis. Did he really die in 1977? Well, television reports seem to indicate that he did, as does the death certificate; and I myself have stood by the graveside in Graceland and seen the headstone, the existence of which is typically, though not absolutely, a sign that, yes, the person whose name is on the stone is dead and buried beneath. Yet theories abound: that he is alive and well and working as a shelf-stacker in a supermarket; or that he’s hiding in the second story of the Graceland mansion (which is suspiciously cordoned off to keep visitors out). My point here is not about silly conspiracy theories, but about the fact that even what would appear to be obvious historical truths are often challenged—and then the question becomes how one adjudicates between competing versions of events. In fact, can one ever so adjudicate? Is my narrative of Elvis’s death simply my truth, and my neighbor’s narrative of Elvis’s continued gainful employment at the local Wawa his truth?

This example is, of course, absurd and trivial—unless, that is, one happens actually to be Elvis or one of his relatives—but there has been a trend over recent decades toward a kind of epistemological nihilism that has so relativized everything that access to the past in any meaningful way is virtually denied; and the more this is the case, the harder it is to argue that the statement “Elvis died in 1977”is a more accurate historical claim than “Elvis spent 2008 working in the Cricklewood Community Center.”

The implications of this can, of course, be much more serious than statements about the current community contributions of “the King.” HD is much more disturbing, both because of its moral implications and because the Holocaust was such a vast event which, one would assume, left a huge amount of historical evidence behind from which to piece together what actually happened. Much of history can be said to be of relatively little immediate consequence; but the Holocaust involved the systematic destruction of human life on a vast scale and continues to shape current events, such as attitudes to the nation-state of Israel. Thus, denying the Holocaust has a clear moral dimension that, say, denying the death of Elvis does not. Further, given the vast amount of apparent evidence for the Holocaust—documentary, photographic, eyewitness, physical—to deny it requires not simply a dramatic revision of established historical wisdom but a wholesale inversion of the same; and, to any casual observer, its denial represents a direct challenge to normal canons of evidence. If historians have tricked us into believing the Holocaust has happened, can we be certain of anything they say?

HD hit the headlines in a most dramatic way in 2000, when British historian David Irving sued American professor Deborah Lipstadt for claiming in her book, Denying the Holocaust, that he was a Holocaust denier.2 Irving chose the British venue because, unlike the American legal code, English libel law does not require proof of malicious intent, and thus he was more likely to obtain a judgment in his favor. What this case did was put on the public stage, in a dramatic fashion, questions that had been perplexing the historical profession for decades: can history tell the truth? Are some narratives more true than others? Can one demonstrate that some claims are simply false? Of course, historical method cannot be established as correct by some legal verdict; but the case provided a unique and, by its context, very exciting opportunity for historians at the top of their game to demonstrate how careful sifting of the various types of evidence available could be used to establish the basic truth that the Holocaust did indeed happen. It also served as a salutary reminder that the game historians play in lecture rooms and seminars, often over matters that are in themselves of no earthly significance, can have important and sometimes frightening implications in the real world. True, Holocaust deniers are far from being postmodernists in their own approach to evidence—they believe that the evidence supports their thesis—but their existence challenges the mainstream historical profession: do our methods and approaches offer us any means of dismantling their arguments?

Still, we are getting ahead of ourselves. The ins and outs of HD will be discussed in greater detail below where we will see that a discussion of HD is extraordinarily instructive in understanding some of the worst fallacies committed by historians. Suffice it to say here, however, that these two examples, the rather wooden but well-intentioned legislation in the state of Florida and the distasteful phenomenon of HD, are prime examples of why good historical method is crucial: we need to avoid the naïveté that just sees history as something “out there,” which we simply dig up and drop into the specimen jar, and the radical epistemological nihilism of those who think that all historical narratives are simply subjective or social constructions that cannot be assessed in relation to each other. As a trio of distinguished UCLA historians expressed the matter:

The relativist argument about history is analogous to the claim that because definitions of child abuse or schizophrenia have altered over time, in that sense having been socially constructed, then neither can be said to exist in any meaningful way.3

The point is well made. It is one thing for historians to play about with notions of epistemological nihilism in the classroom; it is quite another to tell the victim of abuse that such a thing is merely a linguistic construct, a point that may well not be intended as a denial of the victim’s suffering, yet the philosophical subtlety of which is surely lost in translation, so to speak. Yet in order to avoid this radical constructionism, historians need to spend some time reflecting upon the nature of their discipline and upon the limits of what can be done with historical evidence and interpretation.

There are historians who have made a veritable career out of writing books on how to do history while rarely seeming to have gotten around to doing any for themselves. I trust I will not become such; obsession with method is one of the baleful aspects of modern literary theory, and it has not served society well in promoting the reading or writing of literature. Nevertheless, some level of methodological self-awareness is important for those engaged in the writing of history. It can help one understand the nature of evidence, of how much weight can be placed on any single artifact, on what questions can legitimately be asked of certain texts, of how one should select evidence, and what the implications of such selectivity are for the history one then writes.

In order to explore these questions, I have chosen in this book to look at a series of problems relative to the writing of history that can be explored with reference to specific questions and examples. My hope is that, by doing so, readers will not so much buy into some nebulous “Trueman method” for doing history but will be caused to reflect upon how they themselves approach the subject and, even if they find no reason to change that approach, will at least become more self-aware and intentional about it.

In chapter 1, I examine the issue of objectivity in history, using Holocaust Denial as my specific example. Given the fact that no historian is a blank page and that the writing of history is an action of an individual living at a certain time and a certain place, working with all of the personal and cultural baggage that this brings in its wake, we will ask whether the fact that no history can be neutral ultimately means that all historical narratives are inevitably so biased and relative that their claims to historical truth are meaningless. My conclusion is that, while there is no such thing as neutrality in the telling of history, there is such a thing as objectivity, and that varied interpretations of historical evidence are yet susceptible to generally agreed upon procedures of verification that allow us to challenge each others’ readings of the evidence. You might believe that action X is a clear example of class struggle; but I can challenge you by looking at the evidence to see whether your interpretation is plausible, given the status of the evidence. I also argue that all histories are provisional in the sense that no one can offer an exhaustive account of any past action, given the limited state of the evidence and the historian’s inevitably limited grasp of context as well as distance from the past. But provisional merely means limited and subject to refinement; it does not make all readings of the evidence equally valid, or equally unreliable.

In chapter 2, building on the discussion in chapter 1, we will examine issues relating to the idea of interpretative frameworks, those general models of historical action and meaning which historians bring to bear on their task and which shape both the selection and interpretation of evidence. There are various models that I could use as an example of this, but I am going to focus on the one with which I am most familiar: Marxism, particularly as it finds its expression in the works of seventeenth-century British historian Christopher Hill. The purpose of this chapter is not to disparage the notion of grand theory or the kind of schemes of which Marxism is just one of the better-known examples; rather it is to highlight both the strengths and weaknesses of such an approach. On the positive side, Marxism raises awareness of issues that may be hidden below the surface of historical events, and it provides a helpful framework for identifying, collating, and interpreting evidence. On the negative side, it has built into it elements that render it immune to criticism and thus cause it to fall foul of the principle of falsification. Nevertheless, as I will show with a couple of examples, the importance of material factors in shaping historical action is something which Marxism highlights and which is useful even to those who are not committed to Marxist ideology.

In chapter 3,we will address the problem of anachronism.Anachronism is a constant temptation for historians and, to an extent, unavoidable. The writing of history involves a historian in the present addressing questions to the past; inevitably, that involves the bringing together, if not collision, of two different periods in time, with all of the difficulties that brings in its wake. The problem is particularly acute in my own specialist field, that of the history of ideas, where the desire to plunder the past for precedents for present thinking is often a subtle, even imperceptible, pressure that can dramatically impoverish, if not utterly distort, the historical task. In my own thinking in this area, I have been immensely helped by the methodological reflections of Quentin Skinner, and thus examination of his arguments and contributions will be central to the discussion. We will also look at the problem of using anachronistic categories.

In chapter 4, I address what I have called “a fistful of fallacies.” This is far from an exhaustive treatment of all the fallacies to which historians can be prone; nor, to be honest, is every issue addressed therein a “fallacy” in the strict sense of the word. Rather, it is a collection of reflections on particular issues of which the historian should be aware. Most historians, in my experience, just think of themselves as doing history; and there is much to be said for the avoidance of the frankly pretentious and obscurantist language that is so often used by those who spend their time not so much writing history themselves as reflecting on the “theory” of history. Too often representatives of the latter caste are committed to demonstrating that what clearly works in practice cannot work in theory, a rather bizarre, parasitic, and frankly contemptible way to spend one’s life. Having said that, all of us as historians can benefit from being more self-aware about the things we do. There are logical and linguistic mistakes that, once we are aware of them, we are less likely to commit; and this chapter is intended as a guide to them.

Finally, the book concludes with an appendix, a paper delivered at a conference on the reception of John Calvin’s thought, reflecting upon the problems surrounding the connection of thoughts and actions in one era with those in another. Much has been made of the notions of continuity and discontinuity in Christian thought over recent years, and this chapter represents an attempt to address the questions that this raises. It thus stands as an example of methodological reflection on a specific issue in contemporary historical studies.

My approach in this book is, on the whole, to emphasize historians in action and spend less time talking about theory. Theory has enjoyed something of a boom over the last twenty years, to the point where there are now historians who appear to spend all their time writing books about the theory of writing history and rarely do any actual writing of history. While I once used to drive a hard wedge between historians and those who philosophize about history, I have softened over the years and am now fully committed to the idea that every historian needs to be methodologically self-aware and self-critical; yet I still believe that doing history is the historian’s primary calling and the thing that he or she should do best. Thus, the reader will find little discussion of the latest critical theories of history and much of the practicalities of writing history, illustrated with examples. The result is not a scholarly work aimed to impress the critical theorists out there; rather I trust it will be a guide to the perplexed, a useful handbook that will serve to make good students of history more aware of why they are good students of history, and others aware of things they can do to raise their game.

It is my hope that, by the end of the book, readers will have more awareness of the role they themselves play in the writing of history and of the strengths and the limits of the historical task in which they are engaged. As I have already said at the start, there is part of me that thinks that those who can do history, do history; yet, even if nothing I say makes you change how you do history, I trust you will be more self-aware in the way you practice the discipline and this in itself will prove of benefit. Once one knows why and how one thinks and acts the way one does, one is able to sharpen and improve in greater measure than before.

Ultimately, for me, all good historians, no matter what the period which they study, are engaged in asking variations on a basic question: why is this person doing this thing in this way in this place at this particular point in time? Once you realize that that is the kind of question you have been asking all along, you are free to answer it more effectively and to hone your methods to that question more accurately and precisely. The result is better historical consciousness, method, and, hopefully, writing. I trust that this book will provide the reader with some of the key tools to enable such an outcome.

1History News Network, “New Florida Law Tightens Control over History in Schools,” http://hnn. us/roundup/entries/26016.html (accessed August 21, 2006).

2 Deborah Lipstadt, Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (New York: Penguin, 1994).

3 Joyce Appleby, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth about History (New York: Norton, 1994), 6.

One of the popular clichés of contemporary culture is that all truth is relative. As one pop song once expressed it,“This is my truth,now tell me yours.” This relativism has manifested itself within the historical profession over recent decades in terms of a rising epistemological skepticism, if not nihilism, that has tended in the most extreme cases to make all narratives simply projections of the present-day circumstances and opinions of the historian. This has been fuelled in part by the impact of some trends in continental philosophy and literary theory, and also by an increasing realization that the historian’s situatedness, choice of subject, selection of evidence, etc., all have an impact on the nature of the historical narrative that is being constructed. It is now generally accepted that no history is “neutral,”in the sense that it just gives you the facts. Said facts are selected and then fitted together into a narrative by historians who have their own particular viewpoints and their own particular ways of doing things. For example, if I were to sit down and write the history of the French Revolution, various factors would shape the final product: my nationality; my particular approach (am I interested in economics, or literature, or politics?); perhaps even my own views on whether monarchies are a good idea—all of these things will impact how I write and what conclusions I draw. After all,history is not simply “the past”but is a representation of the past by someone in the present; and a history of the French Revolution is a representation of the events to which that term refers by someone who has a variety of commitments that impact the historical task. As John Lukacs defines history,it is“the remembered past,”and as such is inevitably shaped by those who do the remembering.

In this context, claims to neutrality are vulnerable to the kind of criticism launched by Nietzsche in the nineteenth century, and which also resonates with the thought of those other great masters of modern suspicion, Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx: the claim to neutrality is merely a specious means of privileging my point of view—disguised as the simple truth, so to speak—over that of everybody else. I have truth, pure and simple; they have spin, propaganda, hidden agendas, etc. And, even if we do not go all the way with the criticism of a Nietzsche or a Marx, we must acknowledge at the outset that history written without a standpoint is not simply practically impossible—it is also logically inconceivable.

But does this acknowledgment that no history is neutral therefore require that all histories are, ultimately, biased to such an extent that we must acknowledge the validity of all? Is the history that says that John Lennon died in 1980 as valid as the history that claims that he was kidnapped by the CIA and is being held prisoner in Guantanamo Bay? Our instinctive reaction is to say no, of course not. But then the question must be asked: can we justify that claim? Why do we hold that the former is true and the latter false? If no history is neutral, then why can I not resolve the differences in these two narratives by seeing them in terms of the viewpoints of the two historians?

It is in this context that an important distinction needs to be made: the distinction between neutrality and objectivity. Only when this distinction is understood can we begin to see how we can acknowledge the valid insights of much modern and postmodern critical thinking about the practice of history while yet avoid the kind of epistemological anarchy that some would wish to see wreak havoc.

Objectivity Is Not Neutrality

In a popular book on the Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern literature, Peter Enns asks the following question:“Is there really any such thing as a completely objective and unbiased recording of history, modern or premodern?”1 The question is posed rhetorically—after all, what fool would today answer in the affirmative?—and it seems, at first glance, to be a good one; but it also contains a huge assumption that is highly problematic. Perhaps it is unfair to expect a scholar of biblical languages to be familiar with debates from within the historical field, but the assumption that Enns makes is that objective and unbiased seem to be two words for the same thing; and, of course, on the grounds that nobody today would argue for the unbiased nature of any historical writing, the implication is that nobody can argue for the objective nature of historical writing either. Yet most historians would, I believe, both acknowledge the biased nature of the history they write and also maintain that they aspire to be objective in what they do. As we shall see below, the fact that Richard Evans and David Irving approach the Holocaust from specific viewpoints and perspectives does not mean that their respective histories are equally valid; there are ways and means of comparing them that indicate that nonneutrality does not equate to solipsistic subjectivity.

In an impressive study of the American historical profession, Robert Novick has shown that the search for objectivity has been the chimerical goal of the profession for over a century.2 His argument is interesting, not least because he does demonstrate how the ideal of objectivity itself has been transformed over the years. In the late nineteenth century, it is arguable that the notions of objectivity and neutrality were essentially the same thing, with the terms being virtually interchangeable. Over the years, however, a gap has opened up between them. In addition, as at least one significant reviewer pointed out, there is an interesting disjunction in the book between what Novick says and what he actually does. On the face of it, his argument is that the quest for objectivity is a fool’s errand; yet this argument is made in a book which, for me as for numerous other historians, meets what we would regard as decent standards of objectivity. The book is surely not neutral, but its argument is testable by public criteria and demonstrates precisely the kind of method and approach to the evidence that could be described as objective. Sure, Novick has his biases; he is no more able to divest himself of his own prior commitments and opinions and analytical frameworks than anybody else. But he does not write gnostic history that only he and his followers can understand; his arguments are public ones that can be evaluated by others. In arguing against the possibility of objectivity, then, Novick has produced a first-class piece of objective scholarship, a point made pungently by one of his appreciative critics!3

At the heart of the historian’s task is this matter of verifiability and accountability by public criteria, and the criticism of Novick’s approach is to the point: there is a lot of postmodern rhetoric around about the possibility of history and of representing the past, but the bottom line is that most historians do acknowledge in their procedures and methods that such public criteria do exist, and that it is practically possible to make a distinction between a history that asserts that Henry V defeated the French at Agincourt and a history that would even deny the very existence of Henry V. Thus, to demonstrate what is at stake, let us now turn to an extreme modern example of history that is really no history at all.

The Ultimate Test Case: The Holocaust

It is, of course, one thing to play academic games with notions of history, neutrality, and objectivity, but quite another to see where this can lead in its most extreme form. The most notorious example of this is the phenomenon of Holocaust Denial (HD), an approach to the history of the Nazi genocide in Europe between 1933 and 1945 that dramatically downplays the number of people killed and rejects the notion that there was any organized and state-sanctioned campaign of mass murder. To many it seems incredible that such arguments could ever be made with any plausibility; but if historical knowledge is impossible in any ultimate sense, then the Holocaust too, vast and well-documented as it would appear to be, is also negotiable as an object of our knowledge and narratives.

Before we look at how HD functions in terms of historical method, a few preliminary comments are in order. First, it is important to understand that those who argue for HD are generally not radical postmodernists who are skeptical of all claims to historical knowledge. They may deny the Holocaust, but they do not deny the possibility of historical knowledge. Far from it. In fact, the very opposite is the case: they want to argue that the accepted narratives of the Holocaust are wrong, demonstrably wrong, and that their alternative narratives are demonstrably true—or at least more true and coherent as interpretations of the evidence.