20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

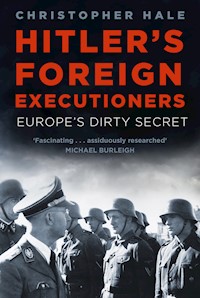

In Hitler's Foreign Executioners, Heinrich Himmler's secret master plan for Europe is revealed: an SS empire that would have no place for either the Nazi Party or Adolf Hitler. His astonishingly ambitious plan depended on the recruitment of tens of thousands of 'Germanic' peoples from every corner of Europe, and even parts of Asia, to build an 'SS Europa'. This revised and fully updated book, researched in archives all over Europe and using first-hand testimony, exposes Europe's dirty secret: nearly half a million Europeans and more than a million Soviet citizens enlisted in the armed forces of the Third Reich to fight a deadly crusade against a mythic foe, Jewish Bolshevism. Even today, some apologists claim that these foreign SS volunteers were merely soldiers 'like any other' and fought a decent war against Stalin's Red Army. Historian Christopher Hale demonstrates conclusively that these surprisingly common views are mistaken. By taking part in Himmler's murderous master plan, these foreign executioners hoped to prove that they were worthy of joining his future 'SS Europa'. But as the Reich collapsed in 1944, Himmler's monstrous scheme led to bitter confrontations with Hitler – and to the downfall of the man once known as 'loyal Heinrich'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Christopher Hale is a documentary producer and non-fiction author. He graduated from the University of Sussex and studied at the Slade School of Fine Art. He has made numerous documentaries for the BBC and other international broadcasters. Hale’s first book, Himmler’s Crusade: The True Story of the Nazi Expedition to Tibet (Transworld Publishers, 2004), won the Italian Giuseppe Mazzotti prize in 2006, and the original hardback edition of Hitler’s Foreign Executioners: Europe’s Dirty Secret (The History Press, 2011) was nominated for the History Today/Longman History Book of the Year. Hale has contributed interviews to a number of broadcasters, including Channel 4 and ZDF in Germany.

The views or opinions expressed in this book and the context in which the images are used, do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of, nor imply approval or endorsement by, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Cover images: Front: © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesty of James Blevins. Back: © Ullstein bild Dtl/Getty Images.

First published 2011

This paperback edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christopher Hale, 2011, 2022

The right of Christopher Hale to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75246 393 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Note on Language

Preface to the 2022 Edition

Introduction

Part One: September 1939–June 1941

1 The Polish Crucible

2 Balkan Rehearsal

3 Night of the Vampires

Part Two: June 1941–February 1944

4 Horror Upon Horror

5 Massacre in L’viv

6 Himmler’s Shadow War

7 The Blue Buses

8 Western Crusaders

9 The Führer’s Son

10 The First Eastern SS Legions

11 Nazi Jihad

12 The Ukrainian SS

Part Three: March 1944–April 1945

13 ‘We Shall Finish Them Off’

14 Bonfire of the Collaborators

15 The Failure of Retribution

Appendix 1 Maps

Appendix 2 Foreign Divisions Recruited by the Third Reich

Appendix 3 Officer Rank Conversion Chart

Appendix 4 Terms & Abbreviations

Notes

Sources

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

One basic principle must be the basic rule for the SS man: we must be honest, decent, loyal, and comradely to members of our own blood and to nobody else … In twenty to thirty years we must really be able to provide the whole of Europe with its ruling class.

Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, 4 October 1943

The Romanians act against the Jews without any idea of a plan. No one would object to the numerous executions if the technical aspect of their preparation, as well as the manner in which they are carried out, were not wanting … The Einsatzkommando has urged the Romanian police to proceed with more order.

Report by Otto Ohlendorf, commander Einsatzgruppe D, 31 July 1941

A Jew in a greasy caftan walks up to beg some bread, a couple of comrades get a hold of him and drag him behind a building and a moment later he comes to an end. There isn’t any room for Jews in the new Europe, they’ve brought too much misery to the European people.

Anonymous Danish SS volunteer

Note on Language

I have taken a pragmatic approach to German terms. Most specialised organisational terms are given in German to begin with and thereafter in English, unless the original has become broadly accepted – ‘Der Führer’ for example. I have referred to SS ranks in German to distinguish them from army ranks. ‘Die Wehrmacht’ in English language books has come to signify the German ground forces – strictly speaking Das Heer. After 1935, the term embraced all the armed forces in the Third Reich, including the army, navy and air force. For this reason I refer to the ‘German army’ rather than ‘the Wehrmacht’. I have treated place names on a case-by-case basis.

Preface to the 2022 Edition

I welcome the opportunity to write a new preface to the paperback edition of Hitler’s Foreign Executioners. I have corrected a number of errors, but stand by the main conclusions of the work. At the time I was researching and writing the book, I encountered a number of defensive military historians who asserted that men who volunteered to join the non-German divisions of the SS were ‘soldiers like any other’, and were recruited for merely expedient reasons. In other words, their motivations had little to do with the racial ideologies of the Third Reich. It is also claimed that, because in 1943 Himmler’s military wing, the Waffen-SS, desperately needed bodies in uniforms to hurl at the advancing Soviet army, the SS jettisoned the racist standards of its founder by recruiting Frenchmen, Belgians, Latvians, Ukrainians and Bosnian Muslims in German-occupied regions of Europe. I argue instead that the recruitment of non-Germans by the SS first in auxiliary police battalions and then full military divisions after 1943 fitted Himmler’s utopian racist plan. He compared his recruitment strategy to ‘harvesting Germanic blood’ that would recover through blood sacrifice the legions of a lost empire. I argue too that many of the Freiwillige or volunteers who served the foreign SS divisions in leadership roles shared a virulent hatred of Soviet communism and its allegedly Jewish origins. The myth of ‘Jewish Bolshevism’ brought together Aryan Germans and their European kin in a malevolent crusade against a racialised enemy. This hatred was an ideological lingua franca that bound together the German architects of genocide and its perpetrators.

The most powerful evidence supporting the argument that the foreign divisions of the Waffen-SS fitted Himmler’s ideological imperatives is provided by the cases of German-occupied Poland and Ukraine. While many Poles took part in lethal attacks on Polish Jews, Himmler refused to authorise a Polish Waffen-SS division because he regarded Poles as an inferior Slavic people. Conversely, in occupied Ukraine Himmler permitted recruitment only from the western Galician region that had been a province of the Austrian Empire before the First World War. In his view, ‘Galicians’ possessed diluted Germanic blood lines that would be enriched by service in the Waffen-SS. He named the division the SS Freiwilligen Division ‘Galizien’. Himmler frequently clarified the racial logic of recruitment in his correspondence with the SS leadership. It was only in the final months of the war that SS recruitment of non-Germans became opportunist and expedient, causing a serious rift between Himmler and Hitler.

When I was researching the book, I discovered that the national memory of the foreign legions of the SS in the newly liberated states of Eastern Europe was highly conflicted and contradictory. After the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, these new states eagerly applied to join the European Union and NATO. A precondition of membership was condemnation of the Holocaust and public acknowledgement of collaborationism in states like Latvia, where the near annihilation of Jewish citizens by the Nazis would have been impossible without the active participation of nationals. The official recognition that tens of thousands of Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians had collaborated in Hitler’s ‘war of annihilation’ that extinguished so many millions of lives considered ‘not worthy of life’ in Nazi ideology was both painful and humiliating to concede. Nevertheless, in the 1990s and 2000s, all central European states recognised the Holocaust and admitted collaboration on entering the EU and NATO. It did not take long for a backlash to gather momentum. Such ‘confessional’ obligations provoked an aggressive nationalist counter-reaction that stressed the suffering of Latvians – rather than Latvian Jews – under Nazi and Soviet occupation and applauded the tens of thousands of Latvians who joined the German Waffen-SS divisions in 1943. Instead of being remembered as collaborators, the Latvian SS volunteers were celebrated as national heroes who gallantly took on the Soviet behemoth as its armies swept into the disintegrating territories of the ‘Greater German Reich’.

The consequences of rendering the crimes of the Soviet Union equivalent to the German Holocaust are already becoming clear in many Eastern European nations. In the Baltic States, Hungary and Ukraine, it is now commonplace to hear politicians imply that wartime collaboration with the Third Reich should no longer be regarded as a moral catastrophe – a stain on the nation. Instead collaboration is increasingly reinterpreted as a pragmatic means to oppose the destructive power of the Soviet Union. This inevitably means that the tens of thousands of men who volunteered to serve the German occupiers as policemen and soldiers can be reinvested as heroic nationalists – no longer vilified as collaborators in genocide. Compelling evidence that this historical lie has begun to take root in Europe can be observed every 16 March in Riga, the capital city of Latvia.

RIGA, 2010

In spring 2010, I travelled to Riga to observe the annual ‘Legion Day’ – a parade by Latvian Second World War veterans. Nothing remarkable about that you might suppose. But you would be wrong; the veterans’ parade I witnessed commemorates the ‘Latvian Legion’ recruited by Heinrich Himmler’s army, the Waffen-SS, in 1943. Surviving members of this SS Legion mourn their fallen comrades in Riga’s cathedral, the Dom, then march to the ‘Freedom Monument’ that stands in central Riga close to the old town.

In 2009, the Latvian SS Legion was splashed across the front pages of British newspapers when David Miliband, then British Foreign Secretary, denounced the Conservative Party for forging links with far-right European parties – including the Latvian For Fatherland and Freedom Party that, Miliband alleged, supported the Nazi Waffen-SS. Miliband’s speech provoked an international storm – from both the Conservative Party and the Latvian government. Timothy Garton Ash, the doyen of historians of Eastern Europe, weighed in: ‘How would you describe a British politician who prefers getting acquainted with the finer points of the history of the Waffen-SS in Latvia to maximising British influence with Barack Obama? An idiot? A madman? A nincompoop?’2

William Hague, now Foreign Secretary, refused to back down. The ‘Latvian Legion’ had nothing to do with the Holocaust, he claimed. The old Legionaries had never been Nazis. Hague went on: ‘David Miliband’s smears are disgraceful and represent a failure of his duty to promote Britain’s interests as Foreign Secretary. He has failed to check his facts. He has just insulted the Latvian Government, most of whose member parties have attended the commemoration of Latvia’s war dead.’ Hague neglected to mention that the ‘Latvian Legion’ refers to two Waffen-SS divisions: the 15th Waffen-Grenadier-Division of the SS (1st Latvian) and the 19th Waffen-Grenadier-Division of the SS (2nd Latvian). These heroes sacrificed their lives for Hitler’s Reich – and its ‘war of annihilation’. Now their surviving comrades will commemorate the memory of the legion as national heroes.

I arrive at Riga airport early on Monday morning. It is bitterly cold and wet; the sky a leaden canopy. Snow is forecast for the following day, 16 March, when the SS commemoration takes place. When I cross the grand Vanšu tilts, or ‘Shroud Bridge’, an hour or so later, faltering sunshine glitters on the broad expanse of the Daugava River. At first sight, Riga resembles any prosperous modern European city. Its wide boulevards are lined with imposing villas, built by a German elite two centuries ago, and swarm with gleaming Mercedes and BMWs. The skyline of the old city is pierced by spindly brick spires – also built by industrious Lutheran Germans. It is hard to escape the shadow of the Teutonic Knights who conquered the Baltic region in the fourteenth century and whose descendants dominated Riga until the end of the First World War. In one Lutheran church, I notice a wall plaque dedicated to a composer and concert meister, Johans Gotfrids Mitels (1728–88), who is also buried as Johann Gottfried Müthel. But Riga is not a fustian museum city. Although the global recession in 2008 hit Latvia hard, pushing up unemployment to 23 per cent, many young Latvians conduct themselves like students all over Europe, crowding into busy new internet cafes, American-style coffee bars and McDonald’s. A rather beautiful tree-lined canal flows through the centre of Riga, crossed by the Freedom Boulevard. At the intersection stands the granite-clad Freedom Monument, built in 1935 to honour the soldiers killed fighting for Latvian independence in 1919. It is a potent symbol of nationhood which has withstood three foreign occupations. Next day, on 16 March, the Latvian SS legionaries would march here from the Dom cathedral and lay wreaths to their fallen comrades.

In 1939, under the secret terms of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, Soviet forces had occupied the Baltic States, instigating a reign of terror and deporting tens of thousands of Latvians. In June 1941 Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, and by early July had driven Stalin’s armies out of the Baltic region. To begin with, many Latvians welcomed German troops as liberators – a pattern repeated elsewhere in the east. But the new masters of Latvia swiftly threw together an occupation regime whose savagery eclipsed the brutality of the Soviets. German administrators amalgamated the three Baltic States into a single entity – the Ostland – effectively abolishing them as sovereign nations. On the heels of the German armies came the Einsatzgruppe, the death squads that unleashed the systematic mass killing of Jewish civilians in a bloody swathe across the Baltic, Belarus and Ukraine. As these death squads moved north towards Leningrad, the German SD (Sicherheitsdienst), an agency of Heinrich Himmler’s SS, began recruiting fanatical young Latvians as auxiliary policemen and used them to murder Latvian Jews. These so-called Schuma battalions proved horribly effective. By October 1941, at least 35,000 Jews had been murdered. In the summer of 1942, SS Chief Heinrich Himmler authorised recruitment of ‘non-German’ Waffen-SS soldiers in neighbouring Estonia – and extended the net to Latvia at the beginning of 1943. According to the Latvian government, more than 100,000 Latvians ended up serving in the German Waffen-SS.3 On 16 March 1944, as the Soviet Army drove Hitler’s armies towards the Baltic, the two Latvian SS divisions fought ‘shoulder to shoulder’ with German SS soldiers against the Russians on the banks of the River Velikaya. It is these events that are commemorated on Legion Day. A few brigades of the Latvian SS that survived these terrible battles ended up defending Berlin, Hitler’s last ‘Fortress City’. After the destruction of the Reich, the Russians rapidly consolidated their occupation of the three Baltic States and turned them into Soviet socialist republics. As Riga’s Occupation Museum insists, this was the second Soviet occupation – and this time the Soviets held the Baltic in an iron grip for nearly half a century. Few Latvians who endured these grim years imagined that the vast Soviet Empire would collapse with such humiliating speed – and that Latvia would once again become an independent nation and part of the European Union.

Freedom is a heady drug. But it can also be a sour blessing. The Latvian government has always insisted that historians in the west are excessively preoccupied with the Holocaust and overlook Soviet crimes. They insist that their nations had suffered equally under Soviet and German occupation. The near destruction of Latvian Jews should never be accorded an elevated moral status overshadowing the fate of other Latvians. Thus German and Soviet crimes became morally equal – and it is this historical relativism that encourages some Latvians to sanction the commemorative rituals of the ‘Latvian Legion’. These veterans did not fight for Hitler – ‘they defended Latvia against the Soviet army.’4

Shortly after I arrive in Riga, I meet Michael Freydman in the ‘Peitava-Shul’, the single Riga synagogue to survive the German occupation, which has recently been restored. Squeezing into a tiny, hemmed-in lot on Peitavas Street, the synagogue is exquisite. As I look for the entrance an edgy police officer watches me warily. Inside, Mr Freydman points out the Hebrew dedication from the Psalms, above the Ark: ‘Blessed is Jehovah who hath not given us/A prey to their teeth.’ Mr Freydman has no time for the moral sophistry that not just forgives but honours men who swore oaths of loyalty to Adolf Hitler as Waffen-SS recruits. He points out that in Latvian schools, students rarely hear the word Holocaust – instead they are taught about ‘the three occupations’. This ‘occupation obsession’ has now become the mantra of amnesia. But the few survivors of the Latvian Holocaust cannot forget that many thousands of their fellow citizens proved all too eager to volunteer as executioners for the Reich. In 1935, some 94,000 Jews lived in Latvia – about 4 per cent of the population. After 1941, the German occupiers and their Latvian collaborators murdered at least 70,000 Latvian Jews in camps, ghettoes and in the countryside; 90 per cent of Latvia’s Jews died as ‘prey to their teeth’. The Legionaries made a choice – and it was the wrong one.

On the afternoon before Legion Day, I catch a train to a tiny station just outside Riga, called Rumbula. Between the railway line and the main road to Riga, there is a silent and enclosed glade of trees. Twisting paths link low concrete rimmed mounds. These are mass graves. Here, at the end of November 1941, SS general and police chief Friedrich Jeckeln and his Latvian collaborators, led by the notorious Victors Arājs, slaughtered more than 27,800 Jews in two days. Himmler admired Jeckeln as a highly proficient mass murderer. He knew he would ‘get the job done’ quickly and efficiently. Jeckeln had invented a ‘system’ that he referred to, with grotesque cruelty, as ‘sardine packing’, which he had honed and refined at killing sites in Ukraine. ‘Sardine packing’ allowed the SS men and their collaborators to ‘process’ many thousands of victims every hour, ransacking their possessions then dispatching them at the edge of a pit. At Rumbula, Jeckeln applied his highly regarded ‘system’ with industrial efficiency – and without mercy. After each day’s ‘work’, the SS men recycled their plunder. Clothes, jewellery, money even children’s toys ended up enriching the lives of supposedly needy German families.

I am the only visitor to the Rumbula memorial site that morning. A few hundred yards away, gleaming Mercedes race along the road to Riga or pull off into a glitzy new shopping mall. Mountains of litter have washed up along the edge of the memorial site. The only sounds are the wind in the trees and the distant rumble of traffic. Latvian historians like to emphasise the macabre fact that Himmler authorised recruitment for the Waffen-SS in Latvia after the majority of Latvian Jews had been murdered. It follows, they claim, that the ‘Latvian Legion’ had ‘nothing to do with the Holocaust’. This callous argument wass put to me on a number of occasions during my visit – most forcefully by Ojārs Kalniņš, the eloquent Director of the Latvian Institute. The claim is a puzzling one. Many of the Latvian police auxiliaries who voluntarily took part in Friedrich Jeckeln’s ‘special action’ at Rumbula, as well as hundreds of other mass shootings of Jewish civilians, later enlisted in the ‘Latvian Legion’.

Tuesday, 16 March 2010. For Latvians, this has been the worst winter for thirty years and overnight temperatures have plummeted. Heavy snow falls and long lines of traffic crawl blindly across the Daugava bridges, generating a sickly yellow haze. A giant Baltic ferry squats in the iced-up river. Snow ploughs rumble through Riga’s old town towards the Dom, where the legion will begin its march to the Freedom Monument. Ice sheaths a red granite memorial to the Latvian ‘Red Rifleman’, recruited by the Russians at the end of the First World War to fight the German Imperial Army – a reminder that two decades later many Latvians backed the Soviets and fought against the Latvian SS divisions.5 Soon after dawn, police vehicles park close to the Dom, engines running to warm the police reserves still sheltering inside. From misted windows, they gaze into the swirling snow, gloomy and bored. Their comrades on duty outside in the blizzard are dressed in beetle-like black armour and helmets.

The thick snow shrouds the towering spire of the Dom, a monument to German Lutheranism. Outside the main entrance, journalists and film crews outnumber police. Cameras flash as elderly men, accompanied by wives, most clutching bunches of Easter flowers, hasten inside. The veterans are like phantoms who return here every 16 March, bringing a chill and unwelcome reminder of the past. On the corner of Doma Laukums square, a knot of old men huddle together, shivering and selling copies of a pamphlet about the ‘Latvian Legion’. A few old men stop to tell their stories, evidently knowing the routine: ‘Forget the SS: we fought for Latvia, for freedom.’ When I arrived at Riga airport I was astonished to see that newspaper stalls sell weighty memoirs written by ‘Latvian Legion’ officers. Since 1991, the organisations that support the veterans have hammered out a shared historical narrative that explains and justifies joining the war on the side of Hitler’s Reich. Although I have contacted Daugavas vanagi, the veterans association, to request an interview, it becomes increasingly clear that these old men are conveyors of the party line, not historical testimony.

The journalists and photographers shivering outside the Dom expect trouble. Inside, camera crews and photographers already gather beneath the tall, plain nave. The Legionaries and their wives fill the front rows beneath the pulpit. A few sit with tears streaming down their cheeks; others glare angrily at the flashing cameras. Outside the Dom’s main entrance, snow is still falling thickly. A sinister honour guard begins to muster. Shaven-headed young men from the nationalist Klubs 415 stand in line beneath a canopy of billowing red and white Latvian flags. Standing to one side are young thugs who had travelled up from Lithuania to support the old Legionaries. They sport white arm bands – modelled on those worn by wartime Lithuanian death squads.

Soon the old Legionaries stumble from the Dom to join these shaven-headed guardians of Baltic national pride, who close ranks around them. The snowstorm at last began to falter. A stern-faced young man takes up a position at the head of the legionary column. Right behind him stands the national leader of the ultranationalist Visu Latvijai (All for Latvia), Raivis Dzintars, and his wife, both clad in Latvian folk costume. The couple add a curious, even kitsch dash of colour – like morris dancers leading a march by a far-right British political party. But there is nothing pretty about Dzintars’ political views: Visu Latvijai aggressively promotes the cause of a mono-ethnic Latvia. Latvia for Latvians! It was this brand of aggressive chauvinism that led many nationalist Latvians to throw in their lot with the German occupiers in 1941.

By now, police battalions are lined up along the route of the march – they stretch like glistening black insects all the way from the Dom to the Freedom Monument, a mile or so away, where the march will end. It is here that Latvians and others opposed to the march have been corralled. At the Dom, the old Legionaries finally set off, led by the peasant couple and the skinhead, his face set hard. Banners ripple in the cold wind. The elderly Legion veterans march briskly through Riga’s old town and then cross the bridge that leads to the Freedom Monument. As the column approaches, ethnic Russian communists shout obscenities: ‘Fuck off! Fuck off!’ As the legion veterans, now shielded by an impenetrable cordon of armed police, begin laying wreaths, high voltage arguments spark up among the crowds.

A short distance behind the police lines stands a smaller, silent group of older men and women – they are Latvian Holocaust survivors. Standing with them today is Ephraim Zuroff, the Director of the Simon Weisenthal Centre, who has fiercely denounced Legion Day, and Josef Koren, a former beekeeper and now leader of the LAK, Latvia’s Anti-Fascist Committee. When a Legion supporter screams at Koren that ‘A soldier is a soldier and all are equal!’ he turns away. Another mantra of Legion defenders is that the volunteers were conscripts – compelled to join. But as Koren points out to journalists, ‘At least 25% of the “Latvian Legion” were volunteers, recruited from the Latvian police who were involved in the murder of Jews and other Latvians – and the SS Legion should not be permitted a celebration of itself in the centre of our city’.

Midday. Sunlight glitters on the Pilsetas canal. The old Legionaries and their honour guard begin to disperse. Soon they have vanished – the mute ghosts of history.

Now there is a carnival atmosphere. At the foot of the Freedom Monument, groups of young Latvians take pictures of each other beside the mass of wreaths and flowers. A young man tells a BBC reporter that for him the old Legionaries are heroes. They defended Latvia. Many thousands of Latvian SS men gave their lives for the freedom of Latvia. These young Latvians look prosperous and happy. They do not shave their heads or sport provocative armbands. But their enthusiasm for the legion is troubling – and unexpected. It would seem that the old Legionaries have become a symbol not of collusion with a murderous foreign occupier but of Latvian national freedom.

It is an outcome that SS Chief Himmler, who was profoundly hostile to the national aspirations of Latvians, could never have foreseen.

I remember the words of the great Latvian poet Ojārs Vācietis:

So all forests are not like this …

I stand and shriek in Rumbula –

A green crater in the midst of grainfields

Introduction

With Germans it is thus, if they get hold of your finger, then the whole of you is lost, because soon enough one is forced to do things that one would never do if one could get out of it.

Viktors Arājs, commander Latvian Arājs Commando1

I really have the intention to gather Germanic blood from all over the world, to plunder and steal it where I can.

Heinrich Himmler2

In the summer of 1944, a racial anthropologist serving with the SS, Oberscharführer Dr Bruno Beger, received an unusual assignment. He was ordered to travel to Bosnia–Herzegovina, then part of the puppet state of Croatia, to prepare a study of ‘races at war’. He would focus on Bosnian Muslims serving in a Waffen-SS division called the ‘Handschar’, meaning scimitar. Its official designation was the 13th Mountain Division of the SS (1st Croatian).3 More than 10,000 Bosnian Muslims had been recruited in the spring of 1943 with the connivance of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin el-Husseini – the Arab nationalist leader then resident in Berlin. The SS issued the Muslim recruits with standard uniforms but permitted them to wear fezzes bearing the death’s head and eagle of the SS. Himmler and the mufti recruited and trained divisional imams who preached the doctrine of ‘Jew hatred’ to the recruits. The following year, as the military situation in the Balkans deteriorated, Beger was transferred to another Muslim SS division based in northern Italy – the Osttürkischer-Verbänd, recruited in the Caucasus. The SS ‘Handschar’ carved a bloody trail of murder and destruction across the Balkans in the final years of the Second World War. The German invasion of Yugoslavia that began in April 1941 had unleashed both massive repression and overlapping civil wars that continue to bedevil this fractured region. The atrocities committed by German sponsored militias like the Croatian Ustasha and Bosnian ‘Handschar’ have never been forgotten or forgiven.

But why did the elite Waffen-SS recruit Bosnian Muslims, an inferior south Slavic people according to Nazi doctrine, to join what Hitler called a ‘war of annihilation’? Why, for that matter, did they recruit Latvians, Ukrainians, Kossovar Albanians, Estonians and a multitude of other non-Germans? To be sure, the recruitment of foreign soldiers, pejoratively labelled mercenaries, has, of course, been a convention of most wars throughout recorded history. The armies mustered by the Persian ruler Xerxes in the fifth century BC, for example, sucked in fighting men from all over the ancient world, including Jews, Arabs, Indians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Phoenicians.4 In modern European history, Napoleon’s Grande Armée boasted divisions and brigades of German, Austrian Dutch, Italian, Croatian, Portuguese and Swiss troops recruited from all over the French Empire and its vassal or allied states.5

The ethnic diversity of the armed forces of the Third Reich far exceeded Napoleon’s Grande Armée. But that is not the principal reason why the recruitment of non-German troops by the Third Reich is surprising and paradoxical. The dogma and practice of the Third Reich was racism so radical that it culminated in mass murder on an unprecedented scale. Hitler characterised National Socialism as ‘a Völkisch and political philosophy which grew out of considerations of an exclusively racist nature.’6 The war launched by Hitler and his generals in September 1939 was intended to begin the task of ‘annihilating’ the racial enemies of the Reich, usually characterised as ‘Jewish-Bolsheviks’, and enslaving Slavic ‘sub-humans’. The outcome would, in theory, be the founding of a new German empire and the complete ‘Germanisation’ of vast tracts of Eurasia. In other words, the German imperial project was by definition a racial undertaking. The ambition of SS Chief Heinrich Himmler was to forge the Waffen-SS as the elite shock troops of this racial imperialism: the apostles of Germanisation. Why then did he recruit apparently non-Aryan Latvians, Ukrainians and Bosnians?

The majority of historians have explained SS recruitment strategy as an expediency that fatally compromised the elite status of the militarised SS. The most recent history of the SS by Adrian Weale asserts: ‘In 1940, [the Waffen-SS] had legitimately been able to claim that it was an elite … by June 1944 … in no military sense could [the bulk of the organisation’s combat units] ever be described as a corps d’elite.’7 This is the latest reformulation of a view that has been repeated ad nauseam by most historians of the SS. In short, they argue, Himmler simply needed bodies in SS uniforms to hurl at the advancing Soviet armies. It was a numbers game – a necessary evil.

In this book I propose a different explanation. The recruitment of non-Germans not only complied with Nazi-sponsored race theory as it evolved during the course of the war, but was a vital component in a master plan hatched up by secretive SS ‘think tanks’. Himmler was despised by many of the Nazi elite as an obsequious and petty-minded bureaucrat – a judgement echoed by many modern historians. This was a sham. Himmler’s imagination was secretive, lethal and boundless. His covert master plan was to build a German empire dominated not by Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP), but the SS. The construction of this SS ‘Europa’ required the complete physical liquidation of every racial enemy of the Reich. At the same time, Himmler and his cadre of SS experts proposed a root and branch re-engineering of European ethnicity. To enact this monstrous scheme, Himmler transformed the SS into a formidable militarised apparatus dedicated to blood sacrifice. SS police battalions and Waffen-SS divisions would become the armed agents of a perverted revolution whose outcome would be a racial utopia. Naturally, Himmler did not discuss these ideas openly, but he provided some tantalising clues about the SS plan in the course of a conversation with Avind Berrgrav, the Archbishop of Norway. SS recruitment, he makes clear, was not a matter of numbers – he wanted the best of the best, the pinnacle of the ‘Germanic’ peoples:

‘Take the regiment Nordland [SS division] as an example,’ Himmler says, ‘Do you believe that we need these men as soldiers? We can do without them! But we mustn’t block these men from freely pursuing their desires. I can assure you that they will return as free and committed supporters of our system.’8

This was not Hitler’s plan. While Himmler dreamt of a future SS ‘Europa’, Hitler clung to the petty minded ideas of the barrack-room bigot. He admired, grudgingly, the British Raj and its subjugation of dark-skinned masses. He despised the Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose, who fled to Berlin to seek German assistance against the British, and dismissed his Indian Legion, recruited by the German army, as ‘a joke’. Himmler regarded Bose and his Indian recruits as members of an ‘Aryan brotherhood’ and he sponsored a German ‘scientific expedition’ to Tibet to look for racial connections between European peoples and Tibetan aristocrats. SS ‘Europa’ was just the beginning. Writing in 1943, Himmler looked forward a few decades to when ‘a politically German – a Germanic World Empire will be formed’. To begin with, Himmler’s master plan embraced only the Nordic peoples of Western and Central Europe. Just as Hitler did, he viewed Eastern Europe as the murky domain of Slavic hordes whose degenerate blood was a mortal threat to European survival. The experience of war changed his mind – and led to a radical rethinking of long-term SS strategy.

At the end of June 1941, Hitler’s armies swept into the Soviet Union. Millions of Soviet soldiers fell into German hands, and were incarcerated in vast open camps built hurriedly in occupied Poland. These camps became instruments of mass murder. More than 2 million Soviet prisoners would perish from disease, deliberate starvation or at the hands of execution squads, many because they ‘looked Jewish’.9 But for German anthropologist Wolfgang Abel, who was attached to an SS agency called the Race and Settlement Office (RuSHA), these hellish camps provided a pseudoscientific treasure trove. Inside this German camp, Abel and his team could examine and measure hundreds of living ‘specimens’ culled from every corner of the Soviet Empire. They soon made some startling discoveries. Abel’s meticulous anthropometric examinations revealed that Germanic blood lines had penetrated far into the east through the Baltic, Ukraine and beyond. In the ‘General Plan East’, hatched up after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, SS scholars had proposed the complete Germanisation of conquered eastern territories. In crude terms, they envisioned liquidating native peoples and importing German settlers. The findings of the ‘Abel Mission’ significantly complicated matters. The simplistic distinction between Germanic and Slavic peoples began to look a lot more intricate.10 These anthropological findings implied that some ‘Eastern’ peoples might possess sufficient ‘Germanic’ blood to qualify as future citizens of the Reich. Later, Himmler would also reconsider the racial status of Balkan peoples like the Bosnian Muslims, the Bosniaks.

But how could these ‘Germanic bloodstreams’ (a phrase used in an SS instructional pamphlet) be exploited? Could this ‘lost blood’ somehow be returned to the Reich, where it belonged? In the perverse logic of German racial ideology, this Germanic blood was merely a latent quality. It was a potent substance, to be sure, but did not necessarily guarantee that its bearers would loyally serve the future Reich. Himmler had a radical solution. He would ‘harvest’ this lost Germanic blood through martial service and blood sacrifice. Himmler revered the pseudoscientific ideas of anthropologists like Hans F.K. Günther, who interpreted race in strictly biological terms. But he also admired ideas promoted by Günther’s rival, the psychologist Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss, and his followers. In books like Rasse und Seele, published in 1926, Clauss had developed a somewhat heretical theory that different races possessed different ‘souls’. Germans, for example, manifested the attributes of a noble Nordic soul; Jews were cursed by their materialistic ‘Semitic’ souls. The details of this gaseous speculation need not detain us here. But the idea of a ‘racial soul’ detached from merely physical attributes implied that race was to some degree malleable. For Himmler, racial identity was also a matter of will, capable in special circumstances of reshaping biological inheritance. According to this cowardly soldier manqué, the supreme manifestation of will was the warrior’s acceptance of the need to kill and be killed. Himmler called the Waffen-SS the ‘assault force for the new Europe’. He believed that military service, sacrifice and, above all, the zealous destruction of the racial enemies of the Reich, could provide the means to remould the racial ‘souls’ of non-German recruits – opening the door to membership of the greater Germanic community.

This master plan did not only apply to the Waffen-SS – the armed SS. The rapid expansion of Himmler’s empire and its security division, the SD (later renamed the RSHA), had begun in the mid-1930s with the takeover of the German police services. For Himmler, there was no fundamental difference between a Reich policeman and a Waffen-SS soldier. Whether a recruit donned the green uniform of the German police or the asphalt grey of the Waffen-SS, he was a warrior dedicated to upholding the security of the Reich; his ‘combat spirit’ (Kampfgeist) would be dedicated to the ‘ruthless annihilation of the enemy’.11 Likewise, after 1939, the first wave of foreign SS recruitment drew in non-Germans as police auxiliaries – ‘Schutzmannschaft’ battalions (known as Schuma). Commanded by German SD officers, these men unleashed a campaign of mass murder directed at their fellow Jewish citizens. From the summer of 1942, Himmler began authorising the recruitment of non-German Waffen-SS units. Many former Schuma men transferred to the new divisions. Himmler’s master plan had astounding consequences. In the summer of 1942, Himmler authorised the formation of an Estonian SS division – then began recruiting Latvians the following year. In 1943, at least 15,000 Bosnian Muslims were admitted to the Waffen-SS. Just over a year later, by the summer of 1944, over 50 per cent of Himmler’s Waffen-SS soldiers had not been born in Germany; every SS division had foreign recruits and nineteen were dominated by non-German recruits.12 At the end of the war, the SS absorbed over a million Soviet Osttruppen (eastern troops), many of them Muslims. Indians, Arabs, Albanians, Croats, Ossetians, Tadjiks, Uzbeks, Bosnians, Ukrainians, Azerbaijanis and even Mongolian Buddhists eventually joined Himmler’s foreign legions.

At the end of April 1945, as Hitler ended his life in the Führerbunker beneath the Berlin Reich Chancellery, a few hundred yards away French, Belgian and Latvian SS men fought alongside German Volksstum and Hitler Youth brigades, vainly struggling to hold back the irresistible deluge of Stalin’s armies. At the same time, at least 10,000 Ukrainian SS men fled west hoping to surrender to the Allies and evade arrest by vengeful Soviet NKVD battalions. All over Europe, the foreign legions of the Reich had to confront the brutal reality of defeat. They cast a long shadow, even today.

A GERMAN HOLOCAUST?

SS foreign recruitment appears to challenge Daniel Goldhagen’s hypothesis that German ‘exterminatory anti-Semitism’ provided the motor of the Holocaust, the systematic mass murder of the Jews of Europe. Goldhagen’s celebrated Hitler’s Willing Executioners was published in 1996. Like Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men, published four years earlier, Goldhagen focused on the German police battalions that had carried out mass shootings of Jews in occupied Eastern Europe. Goldhagen argued that the men who served in these battalions had been typical Germans, saturated in anti-Semitic hatred which made them ‘willing executioners’. He implied that any German provided with the same opportunity to kill would have done the same as the policemen he studied.

According to Goldhagen, the Holocaust was thus a German crime: ‘the outgrowth … of Hitler’s ideal to eliminate all Jewish power.’13 Hitler proclaimed that he wished to kill all Jews – and set about achieving this goal with the enthusiastic connivance of German citizens. Goldhagen claimed that the majority of Germans in the 1930s and 1940s sympathised with Hitler’s plan; the Holocaust was, in this sense, a ‘national project’. Goldhagen characterised so-called ‘good Germans’ as ‘lonely, sober figures in an orgiastic carnival’. He concluded that this ‘set of beliefs’, shared by the majority of Germans, was ‘as profound a hatred as one people has likely ever harboured for another’.14

No other book about the Third Reich has provoked such fierce debate – and, when it was translated and published in the newly unified Germany, so much soul searching. When Goldhagen embarked on a tour of Germany, an army of journalists and photographers pursued him wherever he travelled. It was said he ‘looked like Tom Hanks’ and became a trophy guest on the most prestigious television talk shows. A new generation of Germans seemed to want to wallow in the guilt of their grandparents. But after the grand tour and media commotion came sober analysis. Goldhagen the historian was soon discovered to have feet of academic clay. He was accused of misinterpreting research carried out by other historians, notably Browning, and ignoring any data that did not fit his theory. Historian Eberhard Jäckel called this son of Holocaust survivors a ‘Harvard punk’ and denounced Hitler’s Willing Executioners as ‘simply bad’. But after more than a decade of impassioned debate, Goldhagen’s ‘big bang’ idea still stubbornly refuses to go down quietly. Hitler’s Willing Executioners forced historians to think seriously about the perpetrators of genocide as well as the terrible fate of its many millions of victims.

The question I want to ask in this book is quite simple. Does Goldhagen’s theory of ‘German exterminatory anti-Semitism’ account for the mass killing of Jews and other enemies of the Reich in Croatia, Romania, the Baltic, Belarus and Ukraine and many other regions of Eastern Europe after 1939 at the hands of local militias? How does it explain the eagerness with which hundreds of thousands of young non-German men rushed to join the armed forces of the Reich, above all the Waffen-SS after June 1941? Were these foreign collaborators not also willing executioners? Was the Holocaust not a German crime at all but a European phenomenon? In the case of Eastern Europe, the first major pogrom of the war took place in Romania in the city of Iaşi. As German armies swept into the Baltic nations, Belarus and Ukraine, followed by the SD Einsatzgruppen murder squads, Lithuanians, Latvians and Ukrainians seized the chance to murder their Jewish neighbours in an orgy of seemingly spontaneous mass killings. Eastern Europe was consumed by a spasm of violence that consumed the lives of more than 5 million Jews, while in France, Belgium, Scandinavia and the Netherlands, collaborating militias betrayed, arrested and deported their Jewish fellow citizens to German camps. Many Holocaust perpetrators were not German. Surely, then, we must conclude that these non-German men and women too were Hitler’s willing executioners?

It would appear that Goldhagen simply got it wrong. You did not have to be German to become what French historians call a génocidaire. Many of these foreign collaborators had been reared in national cultures equally infused with anti-Jewish loathing as Germany. Now, the motivations of many tens of thousands of auxiliary policemen and Waffen-SS soldiers are necessarily diverse and hard to define. For every fanatic there is an opportunist or thrill seeker. Apologists for the Waffen-SS foreign volunteers argue that they were soldiers ‘like any other’. Military historians tend not to be interested in ideology – and in the case of the Second World War appear loath to discuss the Holocaust. But combat in the armies of the Third Reich, whether the regular army, the Wehrmacht or the SS police battalions and Waffen-SS, meant signing up to fight in a war that was not at all ‘like any other’, before or since. General Erich Hoepner summed up German military ethics as follows: ‘[the war] is the age old struggle of the Germanic people … the repulse of Jewish-Bolshevism … and must consequently be carried out with unprecedented severity … mercilessly and totally to annihilate the enemy … no sparing of the upholders of the current Russian-Bolshevik system.’15 The enemy was defined not as a body of hostile armed men but as ‘upholders of a system’. According to the perverse ideology of the Reich, any Jew somehow ‘upheld’ the Bolshevik ‘system’ simply by being Jewish. These ‘ethics’ necessarily sanctioned ‘collective forcible measures’ – meaning, in practice, the mass murder of non-combatants whose continued existence threatened the security of the Reich. According to the ethics of annihilation, the killing of unarmed civilians, men, women and children was no longer to be considered ‘collateral damage’ but an integral part of military strategy. The foreign volunteers who joined the various agencies of the Reich clearly understood the ethics of the German war.

As Hitler’s armies swept into the Soviet Union, Reinhard Heydrich, head of the Reich Security Main Office, RSHA, began deploying ‘native’ police auxiliaries to carry out the ‘self-cleansing’ of their homelands. By this he meant mass murder of Jews and communist officials. German SD men and their native collaborators tore through the ancient Jewish communities of the east with unrelenting savagery. As Heydrich and his subordinates understood well, Eastern European nationalists regarded their Jewish neighbours as agents of Bolshevism. This irrational merging of the Jew and the Bolshevik, which was shared by the Germans and their collaborators, was a death sentence for millions. By the end of 1941, German police and Schuma battalions had murdered at least a million Jews in Eastern Europe and the occupied regions of the Soviet Union. In the course of the following year, another 700,000 perished by shooting or in the so-called Reinhardt extermination camps. Millions died in lonely, unmarked forests and meadows in the east.16 And their killers were not only German SS men and solders, but Latvians, Ukrainians and other Slavic servants of the Reich. As killing centres like Treblinka, Sobibór and Auschwitz-Birkenau (which was also a labour camp) took over the business of genocide, the native Schuma battalions ran out of work. It was during this transitional period that Himmler authorised, for the first time, the formation of eastern Waffen-SS legions or divisions. When they became soldiers rather than policemen, these men did not stop murdering Jews.

War is, by definition, a bloody business – so men in uniform tend to be excused a few ‘excesses’. As Ian Kershaw puts it, historians have a ‘tendency to separate the military history of the [1939–45] war from the structural analysis of the Nazi state’.17 A new cadre of historians, led by Omer Bartov, have begun to dismantle artificial firewalls that have been built between politics, ideology and mass murder. The war in the east, Bartov argues, ‘called for complete spiritual commitment, absolute obedience, unremitting destruction of the enemy’.18 ‘Unremitting destruction’ succinctly defines the war Germany fought between 1939 and 1945 – and fighting it irrevocably and profoundly corroded the moral decency of its practitioners whether they were German, French, Latvian or Bosniak.

This book is not a general history of the SS or the Waffen-SS, nor does it set out to provide an exhaustive ‘catalogue’ of every non-German police battalion or combat division. Instead, it analyses in some detail specific case histories that illuminate the recruitment of non-German collaborators as agents of genocide. Part One begins with the German invasion of Poland and the simultaneous development of both a new doctrine of warfare and an ‘armed SS’ charged by Hitler with maintaining security in conquered territory. In Nazi doctrine, security depended on the liquidation of the racial enemies of the Reich. From the very beginning of the war, Himmler used SS police battalions and armed SS units as the vanguard agents of systematic mass murder. During the short Polish campaign, the Germans made only limited use of non-German forces – mainly ethnic Germans and Ukrainians. After the invasion of the Balkans in spring 1941, German-backed native militias like the Ustasha in Croatia and the Iron Guard in Romania embarked on lethal campaigns directed at Jewish citizens. For the Germans, these pogroms provided crucial lessons about the deployment of non-German executioners, strongly implying that a murderous solution to the ‘Jewish problem’ had been hatched up, at least partially, before the summer of 1941.

The Balkan pogroms provided a rehearsal for genocide – and encouraged the SS to cultivate ultranationalist factions in the Baltic and Ukraine. We discover in Part Two that this meant that just days after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, on 22 June 1941, the Einsatzgruppen began recruiting suitable Lithuanians, Latvians and Ukrainians to assist in the arduous tasks of mass murder. At the same time, German military intelligence under Wilhelm Canaris formed two Ukrainian combat battalions known as the ‘Roland’ and ‘Nachtigall’, which also took part in mass killings of Ukrainian Jews. Although the Germans quickly disbanded the two battalions, they demonstrated that combat battalions could also be deployed as mass murderers of unarmed civilians classified as enemies of the Reich.

Eastern Europe was a geographical locus of the worst genocide in history. This is where the SD murder squads were deployed; this is where the Germans built their camps. As a consequence, Eastern European collaborators took a direct role in mass murder, under the auspices of SS commanders. However, the western SS volunteers from France, Belgium and the Netherlands, for example, espoused the same ideological commitment to the destruction of ‘Jewish-Bolshevism’. Recruitment of these ‘Germanics’ had begun in 1940, but gathered pace after the invasion of the Soviet Union. I examine in some detail the case of the notorious Belgian collaborator Léon Degrelle to expose the complex motivations of these ‘crusaders against Bolshevism’. In the summer of 1942, Himmler began authorising recruitment of non-German Waffen-SS divisions in the east, starting in Estonia. This new phase of recruitment accelerated after the destruction of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad – but also reflected a step change in SS thinking about race. By then Himmler had begun to view recruitment as a means to facilitate ‘Germanisation’. As Soviet partisans, pejoratively referred to as ‘Banditen’, began to successfully challenge German security in the occupied east, Himmler mainly used these eastern legions as anti-partisan units. Since the Germans referred to Jews as ‘bandits’, it also meant that the foreign SS divisions continued murdering Jews who had, through whatever good fortune, survived the SD murder squads and extermination camps.

Part Three opens in the summer of 1944, when Himmler’s SS was a militarised state within a state that had been bloated by its recruitment of non-Germans. Despite calamitous military reversals on every front, Himmler continued to think in terms of a Greater Germanic Empire – defended by a pan-Germanic army, toughened by combat and zealous mass murder. Himmler had begun to think ‘beyond Hitler’. The image of Himmler, memorably set out not long after the war ended by Hugh Trevor-Roper in The Last Days of Hitler as the Führer’s most loyal paladin and, in his own mind at least, heir apparent, has rarely been questioned. In the final part of this book, I suggest a more complex interpretation. For Himmler, loyalty was a brand – a means to ascend in the treacherous world of Hitler’s court and to fix the corporate identity of the SS. Affirming loyalty may well have been a psychological necessity for this enigmatic bureaucrat, but Himmler knew that any overt challenge to Hitler would have led to catastrophe. In a succession of barely perceivable steps, Himmler’s ambition began to outstrip Hitler’s. His covert master plan was grounded in an elastic pseudoscientific logic that however lunatic it now appears, inspired a future vision that left the Nazi Party and its leader far behind. ‘Germanisation’ implied both a massive destruction of life alongside the co-option of suitable non-Germans as the dog soldiers of conquest and occupation. For Hitler, war was a means to extract living space in Eastern Europe and impose German hegemony. For Himmler, it was merely the prelude to the ethnic transformation of Eurasia as a Nordic empire.

In March 1945, as the ‘Thousand-Year Reich’ collapsed under Allied hammer blows, these two very different visions finally collided. Hitler excommunicated Himmler and sentenced him to death. The final break was provoked by news of Himmler’s futile contacts with the Allies. But the fuse had been lit years before, and then burned silently out of sight until the downfall of the Reich. The ‘loyal Heinrich’ was no more. But Himmler had little time to enjoy a world without Hitler. Spurned by the provisional new government of Admiral Karl Dönitz, he wandered aimlessly through northern Germany. At the end of May 1945, Himmler, disguised as an officer in the Geheime Feldpolizei (Secret Military Police), was captured by a British army unit. His last reported words, before biting on a cyanide pill concealed in his mouth, were ‘I am Heinrich Himmler’.

Part One:September 1939–June 1941

1

The Polish Crucible

Genghis Khan hunted millions of women and children to their deaths, consciously and with a joyous heart. History sees him only as the great founder of a state.

Hitler, August 1939

On 22 August 1939 Adolf Hitler summoned the German army high command to his southern headquarters in the Bavarian Alps, the Berghof, near Berchtesgaden. The generals and their adjutants tramped past the massed cactus plants in the entrance and assembled in the Great Hall, which was dominated by a giant globe and vast picture window that looked out towards Austria, now absorbed by the Reich. In his study here, Hitler spent many hours sipping tea and gazing at the rocky flanks of Untersberg Mountain where according to legend the red-bearded German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, lies entombed, awaiting a wake-up call to rescue Germany in its hour of need. Hitler would attach Barbarossa’s name to the invasion of Russia in June 1941. He should perhaps have recalled that the German emperor had not perished in battle with the infidel, but had drowned while bathing in an Armenian river.

The German top brass had come to hammer out the objectives of Fall Weiß (Case White), the plan for the invasion of Poland.1 Against the dazzling background of the Bavarian Alps, Hitler unveiled a dizzying vision of conquest. He informed his generals that German relations with Poland had reached a political nadir. Polish provocation was ‘unbearable’ – the only solution was the literal destruction of the Polish nation. This meant that the success of Case White depended on waging a new kind of warfare. Germany, Hitler insisted, would not only be asserting its alleged historic rights to the Polish lands – ‘an extension of our living space in the East’. The task of the German armed forces would be to eliminate a ‘mortal enemy’ of the German Reich: the Polish elite. Hitler clarified what he meant by this: Poland’s ‘vital forces’ (lebendige Kräfte) must be liquidated: ‘It is not a question of reaching a specific line or new frontier, but rather the annihilation of the enemy, which must be pursued in ever new ways.’2 Hitler’s language left no room for ambiguity: ‘Proceed brutally. 80 million people [i.e. Germans] must get what is rightfully theirs.’ At a later meeting he hammered home ‘there must be no Polish leaders, where Polish leaders exist they must be killed, however harsh that sounds’.3

According to his diary account of the earlier meeting, German Army General Franz Halder eagerly concurred: ‘Poland must not only be struck down, but liquidated as quickly as possible.’ The Prussian elite relished this new opportunity to smash the hated Poles who all too often had risen from the ashes of defeat. Now they would be finished off once and for all. Hitler and his generals conceived the Polish campaign as a ‘war of liquidation’. Poland would not simply be conquered but destroyed. ‘Have no pity!’ Hitler insisted. Wehrmacht generals like Halder often used words like ‘liquidation’ and evidently had few misgivings about the ‘physical annihilation of the Polish population’.

Prussian military doctrine had long demanded ‘absolute destruction’ of the enemy’s fighting forces (‘bleeding the French white’ in 1871), as well as the punitive treatment of enemy culture and civilians. But Hitler’s new war strategy insisted on unprecedented ‘harshness’. The problem for his generals was not a moral but a practical one. In purely military terms, liquidation of a nation’s ‘vital forces’ was time consuming and necessarily meant diverting troops from ‘Zones of Operations and Rear Areas’. SS Chief Heinrich Himmler and the oleaginous RSHA head Reinhard Heydrich realised that Hitler’s ‘war of annihilation’ offered astonishing opportunities. The SS would assume responsibility for liquidation, security and ‘mopping-up’ operations, meaning mass executions – onerous tasks best handled by specialised militias that the SS could readily supply. In return, Himmler would demand an ever expanding share of the political and material rewards of occupation.

The Polish campaign of 1939 would provide Himmler with a breakthrough opportunity to transform the SS into the vanguard force of this new kind of war. The destruction of Poland would begin laying the foundations of an embryonic plan to remould the ethnic map of Europe. Although the Germans would deploy few non-German troops in Poland, the war applied SS doctrine for the first time to actual military practice. To understand Himmler’s vision of modern racial war, we need to look at the way the destruction of Poland forged the radical ideology of Hitler’s ‘political soldiers’.