Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

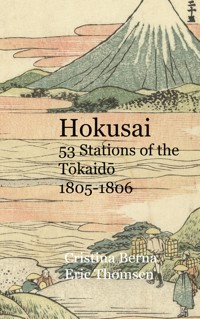

The beauty of art is necessary for happiness. In everyday life the arts give that extra dimension to life that makes it a great adventure. The art and design in buildings, city planning, gardens and parks, roads, bridges, everything that we use daily contributes to a happy and fulfilling life. Ugly buildings, sloppy design, poor quality workmanship, littering and defacing contributes to a miserable life. Why would you want a miserable life? Why would you want to impose a miserable life on others? Hokusai was not only a truly great artist. He also sent a message to common people, who could afford to buy his low cost prints. He conveyed the beauty of majesty, the mount Fujijama, in life. He conveyed the beauty of scenery, he said to people, look around you and see and enjoy the beauty of the scenery. He conveyed the beauty of a good human life , the craftmanship in making the timber, building the boat, fishing, growing tea, enjoying tea with the scenery. The 36 Views of Mt Fuji are religious prints. But different from the typical Christian religious motif the humans are not shown focused on the diety all the time, even if Mt Fuji is shown to have a pervading influence on their lives. The admiration and worship of Mt Fuji is often shown as incidental a single traveler of the group casting a glance at the majestic mountain while the others are busy with the many other things to do. In other words a very realistic rendition on how the divine is taking part in everyday life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 169

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the authors

Cristina Berna loves photographing and writing. She also creates designs and advice on fashion and styling.

Eric Thomsen has published in science, economics and law, created exhibitions and arranged concerts.

Also by the authors:

World of Cakes

Luxembourg – a piece of cake

Florida Cakes

Catalan Pastis – Catalonian Cakes

Andalucian Delight

World of Art

Hokusai – 36 Views of Mt Fuji

Hiroshige – 53 Stations of the Tokaido

and other titles

Christmas Nativity

Christmas Nativity – Spain

Christmas Nativities Barcelona

Christmas Nativities Malaga

Christmas Nativities Sevilla

Christmas Nativities Madrid

Christmas Nativities Luxembourg Trier

Christmas Nativity United States

Christmas Nativity Hallstatt

Christmas Nativity Vienna

Christmas Nativity Innsbruck

Christmas Nativity Salzburg

and more titles

Outpets

Deer in Dyrehaven – Outpets in Denmark

Florida Outpets

Birds of Play

Christmas Markets

Christmas Market Innsbruck

Christmas Market Vienna

Christmas Market Salzburg

Christmas Market Strasbourg

Christmas Market Munich

Christmas Market Nuremberg

Christmas Market Trier

Christmas Market Strasbourg

Christmas Market Copenhagen

and more titles

Missy’s Clan

Missy’s Clan – The Beginning

Missy’s Clan – Christmas

Missy’s Clan – Education

Missy’s Clan – Kittens

Missy’s Clan – Deer Friends

Missy’s Clan – Outpets

Missy’s Clan – Outpet Birds

and more titles

Vehicles

Copenhagen vehicles – and a trip to Sweden

Construction vehicles picture book

Trains

American Police Cars

American Fire Engines

American Vintage Fire Engines

American Air Rescue

American National Guard

and more titles

Contact the authors

Published by www.missysclan.net

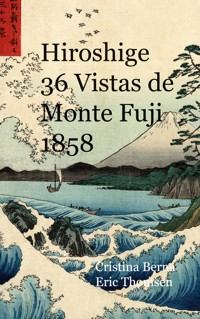

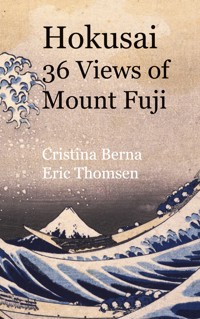

Cover picture: No 1 The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Inside no 1: No. 14 Umegawa in Sagami province

Inside no 2: No 23 Sazai hall - Temple of Five Hundred Rakan

Contents

Introduction

Katsushika Hokusai

Mount Fuji

Edo Period 1615-1868

Bushido

Japanese Historical Periods

Common Japanese Print Sizes

Woodblock printing in Japan

Chinese Landscape Painting

No 1

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

No 2

South Wind, Clear Sky

(

Red Fuji

)

No 3

Rainstorm Beneath the Summit

No 4

Under Mannen Bridge at Fukagawa

No 5

Sundai, Edo

No 6

Cushion Pine at Aoyama

No 7

Senju, Musashi Province

No 8

Tama River in Musashi Province

No 9

Inume Pass, Kōshū

No 10

Fuji View Field in Owari Province

No 11

Asakusa Hongan-ji temple in the Eastern capital, Edo

No 12

Tsukuda Island in Musashi Province

No 13

Shichiri beach in Sagami Province

No 14

Umezawa in Sagami Province

No 15

Kajikazawa in Kai Province

No 16

Mishima Pass in Kai Province

No 17

A View of Mount Fuji Across Lake Suwa (Lake Suwa in Shinano Province)

No 18

Ejiri in Suruga Province

No 19

Mount Fuji from the mountains of Tōtōmi

No 20

Ushibori in Hitachi Province

No 21

A sketch of the Mitsui shop in Suruga in Edo

No 22

Sunset across the Ryōgoku bridge from the bank of the Sumida River

No 23

Sazai hall - Temple of Five Hundred Rakan

No 24

Tea house at Koishikawa. The morning after a snowfall

No 25

Lower Meguro

No 26

Watermill at Onden

No 27

Enoshima in Sagami Province

No 28

Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tōkaidō

No 29

Yoshida at Tōkaidō

No 30

The Kazusa Province sea route

No 31

Nihonbashi bridge in Edo

No 32

Barrier Town on the Sumida River

No 33

Bay of Noboto

No 34

The lake of Hakone in Sagami Province

No 35

Mount Fuji reflects in Lake Kawaguchi, seen from the Misaka

No 36

Hodogaya on the Tōkaidō

No 37

Honjo Tatekawa, the timberyard at Honjo, Sumida

No 38

Pleasure District at Senju

No 39

Goten-yama-hill, Shinagawa on the Tōkaidō

No 40

Nakahara in Sagami Province

No 41

Dawn at Isawa in Kai Province

No 42

The back of Fuji from the Minob uriver

No 43

Ōno Shinden (the paddies) in Suruga Province

No 44

The Tea plantation of Katakura in Suruga Province

No 45

The Fuji from Kanaya on the Tōkaidō

No 46

Climbing on Fuji

References

Websites

Introduction

The beauty of art is necessary for happiness.

In everyday life the arts give that extra dimension to life that makes it a great adventure.

The art and design in buildings, city planning, gardens and parks, roads, bridges – everything that we use daily contributes to a happy and fulfilling life.

Ugly buildings, sloppy design, poor quality workmanship, littering and defacing contributes to a miserable life.

Why would you want a miserable life? Why would you want to impose a miserable life on others?

Hokusai was not only a truly great artist.

He also sent a message to common people, who could afford to buy his low cost prints.

He conveyed the beauty of majesty, the mount Fujijama, in life.

He conveyed the beauty of scenery – he said to people – look around you and see and enjoy the beauty of the scenery.

He conveyed the beauty of a good human life – the craftmanship in making the timber, building the boat, fishing, growing tea, enjoying tea with the scenery.

The 36 Views of Mt Fuji are religious prints. But different from the typical Christian religious motif the humans are not shown focused on the diety all the time, even if Mt Fuji is shown to have a pervading influence on their lives.

The admiration and worship of Mt Fuji is often shown as incidental – a single traveler of the group casting a glance at the majestic mountain while the others are busy with the many other things to do. In other words a very realistic rendition on how the divine is taking part in everyday life.

Cristina and Eric

Katsushika Hokusai

Katsushika Hokusai (c. October 31, 1760 – May 10, 1849) was a Japanese artist, painter and printmaker in Edo (Tokyo) period 1760–1849.

Hokusai established landscape as a new print genre in Japan.

At a young age, Hokusai was adopted by an uncle who held the prestigious position of mirror polisher in the household of the shogun, the commander-in-chief of feudal Japan. It was assumed that the young Hokusai would succeed him in the family business, and he likely received an excellent education in preparation for a job that would place him in direct contact with the upper class. In 19th-century Japan, learning to write also meant learning to draw, since the skills and materials required for either activity were almost identical.

When Hokusai’s formal education began at age six, he displayed an early artistic talent that would lead him down a new path. He began to separate himself from his uncle’s trade in his early teens—perhaps because of a personal argument, or perhaps because he believed polishable metal mirrors would soon be replaced by the silvered glass mirrors being imported by the Dutch— and worked first as a clerk at a lending library and then later as a woodblock carver. At age 19, Hokusai joined the studio of ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunshō and embarked on what would become a seven-decade-long career in art.

Self portrait of Hokusai as an old manhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hokusai_portrait.jpg

Hokusai was never in one place for long. He found cleaning distasteful—instead, he allowed dirt and grime to build up in his studio until the place became unbearable and then simply moved out. The artist changed residences 93 times throughout his life. Hokusai also had difficulty settling on a single moniker.

Although changing one’s name was customary among Japanese artists at this time, Hokusai took the practice even further with a new noms d’artiste roughly each decade.

Together with his numerous informal pseudonyms, the printmaker claimed more than 30 names in total. His tombstone bears his final name, Gakyo Rojin Manji, which translates to “Old Man Mad about Painting.”

Hokusai was also a savvy self-promoter, creating massive paintings in public with the help of his students. At a festival in Edo in 1804, he painted a 180-meter-long portrait of a Buddhist monk using a broom as a brush. Years later, he publicized his best-selling series of sketchbooks with a three-story-high work depicting the founder of Zen Buddhism.

Hokusai was one of the 19th century’s leading designers of toy prints—sheets of paper meant to be cut into pieces and then assembled into three-dimensional dioramas. He also made several board games, one of which depicted a pilgrim’s route between Edo and nearby religious sites. Consisting of several small landscape designs, it probably served as a precursor for his eventual masterpiece, the series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” (ca. 1830-32). He illustrated countless books of poetry and fiction, and even published his own how-to manuals for aspiring artists. One of these guides, titled Hokusai Manga (1814-19) and filled with drawings he originally made for his students to copy, became a best-seller that gave the artist his first taste of fame.

Although Hokusai was prosperous in middle age, a series of setbacks—intermittent paralysis, the death of his second wife, and serious misconduct by his wayward grandson—left him in financial straits in his later years. In response, the elderly artist funneled his energy into his work, beginning his famous series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” (which included The Great Wave) in 1830.

Another catalyst for the iconic set of images was the introduction of Prussian blue to the market. As a synthetic pigment, it lowered the price enough that it became feasible to use the shade in prints for the first time. Although The Great Wave made his name monumental, he was already a famous artist by this time, in his seventies. His publisher of the 36 Views of Mt Fuji This number is due in part to the exceptional length of his career, which officially began in 1779 and lasted until his death in 1849 at the age of 89. Hokusai was also intensely productive, rising with the sun and painting late into the night. Although a fire in his studio destroyed much of his work in 1839, he is thought to have produced some 30,000

paintings, sketches, woodblock prints, and picture books in total. His last words were said to have been a request for five or 10 more years in which to paint.

During Hokusai’s life, the Japanese government enforced isolationist policies that prevented foreigners from entering and citizens from leaving. However, that didn’t stop his work from influencing some of the biggest names in Western art history. When Japan opened its borders in the 1850s, Hokusai’s work crossed continents to land in the hands of artists such as Claude Monet, who acquired 23 of the Japanese artist’s prints.

Above: a print of Hokusai painting the Great Daruma in 1817.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hokusai_Daruma_1817.jpg

Edgar Degas also took cues from Hokusai, in particular his thousands of sketches of the human form. The rapid embrace of his prints by European artists may have been in part due to his use of a Western-style vanishing point perspective. Other print designers in Japan employed the Asian perspective, which positioned far-away objects higher on the picture plane, an effect that, to a Western eye, made it appear as though the ground was tilting upwards.

The mark of Eijudö, the publishers of the series 36 Views of Mt Fuji is often found in the prints – humorously placed on saddle bags etc. A rare print of the first owner, Nishimuraya Yohachi I, on his seventyfirst birthday can be seen at the Honolulu Museum of Art, which has a large collection of Hokusai’s work.

Kawasa Hasui: Fuji at Dawn https://ukiyo-e.org/image/jaodb/Kawase_Hasui-Haibara_Fan_Shop_Series-Mt_Fuji_at_Dawn-00037940-050621-F06

Mount Fuji

Mount Fuji(富士山Fujisan) is the highest mountain in Japan at 3,776.24 m (12,389 ft) and 7th-highest mountain on an island. Mount Fuji located on Honshu Island. It is an active stratovolcano that last erupted in 1707–1708. Mount Fuji lies about 100 kilometers (60 mi) south-west of Tokyo, and can be seen from there on a clear day.

Mount Fuji's exceptionally symmetrical cone, which is snowcapped for about 5 months a year, is a well-known symbol of Japan and it is frequently depicted in art and photographs, as well as visited by sightseers and climbers.

Mount Fuji is one of Japan's "Three Holy Mountains" (三霊山Sanreizan) along with Mount Tate and Mount Haku. It is also a Special Place of Scenic Beauty and one of Japan's Historic Sites. It was added to the World Heritage List as a Cultural Site on June 22, 2013

The volatility of the volcano itself is discussed. Fuji has erupted at least 75 times in the last 2,200 years, and 16 times since 781. The most recent flare-up—the so-called Hoei Eruption of 1707—occurred 49 days after an 8.6 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast and increased the pressure in the volcano’s magma chamber.

Huge fountains of ash and pumice vented from the cone’s southeast flank. Burning cinders rained on nearby towns—72 houses and three Buddhist temples were quickly destroyed in Subasiri, six miles away—and drifts of ash blanketed Edo, now Tokyo. The ash was so thick that people had to light candles even during the daytime. The eruption was so violent that the profile of the peak changed. The disturbance triggered a famine that lasted a whole decade.

Since then the mountain has been quiet. It’s been quiet for so long is is said that natural disasters strike about the time when you forget their terror.

Fuji is venerated as a stairway to heaven, a holy ground for pilgrimage, a site for receiving revelations, a dwelling place for deities and ancestors, and a portal to an ascetic otherworld.

Religious groups have multiplied in Fuji’s foothills. Among the more than 2,000 sects and denominations are those of Shinto, Buddhism, Confucianism and the mountain-worshiping Fuji-ko. Shinto, an ethnic faith of the Japanese, is grounded in an animist belief that kami (wraiths) reside in natural phenomena—mountains, trees, rivers, wind, thunder, animals—and that the spirits of ancestors live on in places they once inhabited.

Kami wield power over various aspects of life and can be mollified or offended by the practice or omission of certain ritual acts. The notion of sacrality, or kami, in the Japanese tradition recognizes the ambiguous power of Mount Fuji to both destroy and to create, which is shown by Hokusai in the 36 Views of Mt Fuji.

It is powerful for any culture to have a central, unifying symbol and when it is one that is equal parts formidable and gorgeous. By showing life itself in all its shifting forms against the unchanging form of Fuji, with the vitality and wit that informs every page of the book, Hokusai sought not only to prolong his own life, but in the end to gain admission to the realm of Immortals.

Views of Mount Fuji series. It was owned first by Nishimuraya Yohachi I.

The Honolulu Museum of Art has a print dated c. 1797-1798 of the aged publisher seated in formal attire on his bedding. He grasps a folded fan while reading a book on a black and gold lacquered stand with the mark of his business. His robes are also decorated with the character ju (“long life”), part of the name Eijudö.

Print showing owner of Nishimura Yohachi publisher Eijudö ca 1797-98.Edo Tokyo Museum https://data.ukiyo-e.org/etm/images/0196200353.jpg

There is no doubt that his work was spurred by the publisher Eijudö, the company that published Hokusai’s Thirty-six

The painted screen behind him depicts themes symbolic of the New Year. The rising sun above Mount Fuji, a hawk, and eggplants are three of the most auspicious subjects to dream about during New Year’s festivities. It is likely that this rare print was issued privately to celebrate both the New Year and Nishimura Yohachi’s longevity.

Mount Fuji had an enduring significance for the Nishimura family, and the descendant who published Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views in the period c. 1830 – 1834 was a prominent member of the Fuji Cult that became popular in the late Edo period.

Japanese: ‘western village’, a common place name and surname; the surname is found mostly in northeastern Japan and the island of Okinawa. Some bearers are of samurai descent.

For centuries, religious devotees, or ascetics, looked towards Mount Fuji as a place of worship, trekking up the mountainside to reap its spiritual powers. The mysterious lava caves were thought of as “human wombs,” and those who journeyed through the dark passageways could experience rebirth.

Devotees and pilgrims of the cult of Mount Fuji often ventured through the chain of caves either on their way to Mount Fuji or on their descent back. While many of the caves were used for spiritual practices, there was one “womb cave” that has been singled out as the mother of all caves at Fuji, The cave known as Tainai, which translates to ”womb” is said to be the birthplace of Sengen, the deity of Mount Fuji. It was common for the religious followers of the Mount Fuji cult to associate terrestrial features of the mountain with parts of the human anatomy.

Certain rocks were called navel cords or placentas, while bell-shaped stalactites were referred to as breasts, the water dripping down considered milk of the mountain. A person who crawled through the cave carried a white cotton cloth that was used to collect the milk dripping from the rock breasts.

Once soaked, the cloth was brought back down and used for several purposes for pregnant women and new mothers. The cloth was placed in a mother’s drinking water so the powers from the mountain could aid in delivery or help mothers or nursing women who could not produce breast milk.

The dark cavern of Tainai had low ceilings, and the pilgrims would place straw sandals on their knees to protect them while they crawled. They lit candles to find their way through the cavern, and brought the candles home when family mothers gave birth. Shorter candles (ones that burned for longer in the cave) were thought to aid in short labor and quick delivery.

Sometime around the turn of the 17th century, Kakugyō

Tōbutsu founded another famous spiritual cave on the western flank of the mountain called Hito-ana, literally “man hole.”

According to legend, Hito-ana was believed to be the deity’s residence and an entrance to another world. Kakugyō,

who has been deemed the father of the Mount Fuji cult, sought the power of the mountain and received a prophecy to go to the cave. He became known as the man in the cave, residing and practicing in the Hito-ana for seven days.

Not everyone could revel in wonders of Mount Fuji’s lava caves. Until 1868, women were banned from climbing higher than the middle zone of the mountain, ascetics worrying that they would distract men from their religious duties and other traditional taboos. Some male devotees also couldn’t climb due to physical or economic reasons.

When you look at the 36 Views of Mt Fuji, you feel the powerful influence of the Fuji cult in the meanings and messages you can read from them, when you are aware of these religious cults.

Taken on their own each print, which consist of the original 36 Views plus another surviving 10, making them a total of 46, are incredible works of art masterfully executed for printing and sale to a large public, using wood block printing.

When read in the light of Japanese culture and Japanese spiritual thinking, the 36 Views of Mt Fuji takes on a deeper meaning that Westerners do not perceive at first sight.

Unknown artist: Dragon arising from the sea and climbing Mt Fuji (1890-1920) LoC

https://ukiyo-e.org/image/loc/01939v

Edo Period 1615-1868

Japan’s Edo period dates from 1615 (some say 1603) , when Tokugawa Ieyasu defeated his enemies at Osaka Castle, to 1868, when the Shogun’s government collapsed and the Meiji emperor was reinstated as Japan’s main figurehead.

This 250-year period takes its name from the city of Edo that started out as a small castle town and grew into one of the largest cities of the modern world, now called Tokyo. Much of this tremendous growth happened during the Edo period.