Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

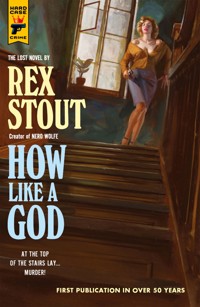

STAIRWAY TO HOMICIDE In the shadowy stairwell of a New York City brownstone, a man stealthily begins to climb. In the pocket of his coat, a loaded revolver. At the top of the stairs, a woman he intends to kill. But who…? This extraordinary novel by Rex Stout, the legendary creator of Nero Wolfe, is a psychological thriller like none you have ever read. As William Sidney climbs the stairs, you'll dive deep into his troubled past, uncovering scandalous secrets and deceptions. And all the while, step by creeping step, he draws closer to a shocking act of violence… Unpublished for more than 50 years, HOW LIKE A GOD is the earliest masterpiece by an author who would later be named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America and become world famous for creating one of the most enduring characters in the mystery genre.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

A

I

B

II

C

III

D

IV

E

V

F

VI

G

VII

H

VIII

I

IX

J

X

K

XI

L

XII

M

XIII

N

XIV

O

XV

P

XVI

Q

Acclaim for the Workof REX STOUT…

“Rex Stout is one of the half-dozen major figures in the development of the American detective novel.”

—Ross Macdonald

“Splendid.”

—Agatha Christie

“[Stout] raised detective fiction to the level of art. He gave us genius of at least two kinds, and a strong realist voice that was shot through with hope.”

—Walter Mosley

“Those of us who reread Rex Stout do it for…pure joy.”

—Lawrence Block

“The story has everything that a good detective story should have—mystery, suspense, action—and…the author’s racy narrative style makes it a pleasure to read.”

—New York Times

“One of the most prolific and successful American writers of the 20th century…The writing crackles.”

—Washington Post

“Practically everything the seasoned addict demands in the way of characters and action.”

—The New Yorker

“One of the master creations.”

—James M. Cain

“You will forever be hooked on the delightful characters who populate these perfect books.”

—Otto Penzler

“Premier American whodunit writer.”

—Time

“The man can write, that is sure.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“One of the brightest stars in the detective and mystery galaxy.”

—Philadelphia Bulletin

“Unfailingly wonderful.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Dramatic and credible.”

—Boston Globe

“Rex Stout is as good as they come.”

—New York Herald Tribune

“Unbeatable.”

—Saturday Review of Literature

“What a pleasant surprise for Stout fans…an unexpected treasure from one of the grand masters of mystery.”

—Booklist

He became suddenly aware that his hand was again in his overcoat pocket, closed tightly over the butt of the revolver. His hand came out and the revolver with it, and he stood there with his forearm extended, the weapon in plain sight, peering around, downstairs and up, like a villain in a melodrama. If the door of the landing had at that instant opened and one of the art students had appeared, he would probably have pulled the trigger without knowing it.

His hand returned to his pocket and then came out again, empty, and sought the railing as he mounted another step, and another, and then stopped once more.

Oh you would, would you, he said to himself, and he felt his lips twist into a grimace that tried to be a smile. No you don’t, you don’t go back now, this time you go ahead, if it’s only to point it at her and let her know what you think she’s fitfor.…

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKS YOU WILL ENJOY:

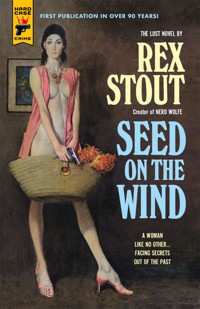

SEED ON THE WIND by Rex Stout

JOYLAND by Stephen King

THE COCKTAIL WAITRESS by James M. Cain

THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH by Ariel S. Winter

BRAINQUAKE by Samuel Fuller

EASY DEATH by Daniel Boyd

THIEVES FALL OUT by Gore Vidal

SO NUDE, SO DEAD by Ed McBain

THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES by Lawrence Block

QUARRY by Max Allan Collins

SOHO SINS by Richard Vine

THE KNIFE SLIPPED by Erle Stanley Gardner

SNATCH by Gregory Mcdonald

THE LAST STAND by Mickey Spillane

UNDERSTUDY FOR DEATH by Charles Willeford

A BLOODY BUSINESS by Dylan Struzan

THE TRIUMPH OF THE SPIDER MONKEY by Joyce Carol Oates

BLOOD SUGAR by Daniel Kraus

DOUBLE FEATURE by Donald E. Westlake

ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman

KILLER, COME BACK TO ME by Ray Bradbury

FIVE DECEMBERS by James Kestrel

THE NEXT TIME I DIE by Jason Starr

LOWDOWN ROAD by Scott Von Doviak

FAST CHARLIE by Victor Gischler

NOBODY’S ANGEL by Jack Clark

DEATH COMES TOO LATE by Charles Ardai

INTO THE NIGHT by Cornell Woolrich and Lawrence Block

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-164)

First Hard Case Crime edition: June 2024

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1OUP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright ©1929 by Rebecca Bradbury, Chris Maroc, and Liz Maroc, renewed 1957

Cover painting copyright © 2024 by Ricky Mujica, from reference by Robert Maguire

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-80336-486-5

E-book ISBN 978-1-80336-487-2

Design direction by Max Phillips www.signalfoundry.com

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

HOW LIKE A GOD

A

He had closed the door carefully, silently, behind him, and was in the dim hall with his foot on the first step of the familiar stairs. His left hand was in his trousers pocket, clutching the key to the apartment two flights up; his right hand, in the pocket of his overcoat, was closed around the butt of the revolver. Yes, here I am, he thought, and how absurd! He felt that if he had ever known anything in his life he knew that he would not go up the stairs, unlock the door, and pull the trigger of the revolver.

She would probably be sitting in the blue chair with many cushions, reading; so he had often found her. He shivered so violently that he almost lost his balance as his foot found the next step.

His mind seemed suddenly clear and intolerably full, like a gigantic switchboard, with pegs in all the holes at once and every wire humming with an unwonted and monstrous burden. A vast intricacy of reasons, arguments, proofs—you are timid and vengeless, you are cautious and would be safe, you would be lost even if safe, you are futile, silly, evil, petty, absurd—he could not have spoken in all his years the limitless network of appeals, facts, memories, that darted at him and through him as his foot sought the third step.

He heard them all.…

I

You are timid and vengeless.

When you first saw that word you were in short pants and numberless words in the books you read were strange and thrilling. Many of them have long since been forgotten, many more have lost their savor. To become common and flat is sadder than to disappear; but this word has escaped both fates through the verses you wrote, using it in the first line of each stanza. Afraid of your father’s and mother’s good-natured criticism, you showed them only to Mrs. Davis, the Sunday School teacher.

“Vengeless,” she said, “is not used for men and women, only for impersonal things like time and tides.”

That was before she invited you to her house in the afternoon, but already she was smiling at you. You were mortified at having misused the word and tore the verses up.

That was timid, and you hated yourself for it without really knowing it. You were always hating yourself without knowing it; the tiniest spark was enough to set off that firecracker. Jane, who had the trick of being aware of things before they quite happened, was always on to you, not unkindly, but that kindness could crush you. Did Jane know that? Years later she did, of course, with Victor and her children, and her friends and committee meetings, but at raw and gawky twelve, just outgrown her dolls, did she already mysteriously know what she was doing to people? She would be peeling potatoes and would turn to your mother:

“Better give Billy a cookie; he’s done something in school.”

“Let me alone,” you would almost whimper. Then your mother, with that pretense of equality which you resented without understanding why:

“Don’t you want to help your sister do the potatoes?”

You always intended to refuse the cookie, but you never did. Come to think of it, there was no reason why you should; but it always seemed a surrender. In youth the sources of ignominy were everywhere, or you more tenderly felt them.

The most blatant and poignant timidity of those young Ohio days was when, with the boys down on the lot below Elm Street of a summer afternoon, you would try to steal second base. Why in the name of god did you ever try it? That was peculiarly not your dish, you always knew that and yet forever you tried it. There were three moments of agony: do I go on this pitch? Just that one instant too long on the decision, the bad delayed start—but the running was splendid. You could run. The slide, torture, whether headfirst or hook. A kicked face or a turned ankle? The essential wild precise plunge. You knew what was required, but you didn’t have it. There you were, a yard away from the base, with the ball on you, and from all sides the friendly triumphant jeers. If Jane had been there doubtless she would have offered you a cookie, and you would have killed her.

Oh, that!

But during this period that vague and oppressive timidity had its usual seat at home, at the little house on Cooper Street. Probably its unknown focus was Jane, for your father and mother were from first to last nebulous and ill-defined; they seemed to float around you; and your other sisters and brothers existed only as pestiferous facts, hardly yet as persons. Larry was only five, and Margaret and Rose were being born or at least scarcely out of the cradle.

How easy to see now that that house meant Jane. There was the time, somewhat later, that you stumbled into the bathroom with a bleeding nose, bruised souvenir of a visit of the lime-kiln gang to peaceful Cooper Street, and found there your mother and Jane, both naked, one fresh from the tub, the other just getting in. It was a dilemma. Outside was the carpet, not to be bled on; here was your imminent pain. They helped, somehow, hurriedly; Jane handed you a towel, or was it your mother? It was an exciting and confusing experience, and the memory is blurred. There was throughout a portentous embarrassment, even after your mother got a robe around her. Jane didn’t bother. That night the pink living skin you saw behind closed eyelids was Jane’s; also the other nights; never your mother’s. Timidity? You shrank from the warmth that crept tingling into your own skin at the forbidden memory. You at once invited it and denied it. Not so would Jane have done! Was she embarrassed that day? You wondered about that ceaselessly, until the dignity of new juices and new purposes drove it underneath.

With your father there was timidity too, but as you see now perfumed with contempt. Not even you could have been really timid with that little herring of a man who meant invariably well and went around with the air of one who is always expecting to hear a bell ring. There is not more good will in all heaven than he carried in his heart; The first dream you dreamt that was in touch with reality came when his business and his health lost step together and you were shocked and pleased to find yourself taken seriously as a member of the family.

“Bill, it’s up to you,” said your father, after your mother’s tears were dried and the younger children had been sent from the room. “Doc’s crazy. I’ll be at it again in a month. You’re nineteen, and big enough to handle two real drug stores, let alone that little hole in the wall. Nadel can do the prescriptions, and, with all the afternoons and Saturdays you’ve had there…”

“He can’t do it,” said Jane, home for the summer from Northwestern. No, she was through then, and was teaching Latin in the high school like a goddess waiting at a railroad station for a train. Anyway, “He can’t do it” was what she said, and when you grunted protest she added:

“You know you can’t, Bill. It’s not your line, and anyway you’re too young and it’s not fair. I’m the one for it, and Dad will have to let me.”

Your father, curiously persistent, had Mr. Bishop come in and empowered you to sign checks, but no one was fooled by that empty symbol except your mother. The summer dragged endlessly, with the intimate and inane activity of the leading drug store of a growing town. You resented Jane bitterly as she competently kept patent medicine salesmen where they belonged while you mixed ice cream sodas and washed the glasses; and by July you found it almost impossible to talk to her. It was just then that Mrs. Davis went to Cleveland—ah, you still wonder, how much of that did Jane know? At all events, the whole world was dark. But your father, to the pleased but professionally discomfited surprise of Doc Whateley, pulled on his trousers again, “slightly disfigured but still in the ring” as the editor of the weekly Mail and Courier put it, and you went off for your second year at college.

That was the year that saw your legend created and made you a man of mark. You have never understood that episode, especially not when you were acting it; it was an astonishing contradiction of all timidities and inadequacies; what would have happened and where would you be now if Mrs. Moran had not done your washing and sent little Millicent to fetch it, and deliver it, twice a week? It was on her second or third visit that you noticed her and became intensely aware that that pale child was handling the things you had worn. It was indefinable and incredible; she was exactly ten, half your own age, pallid and scarcely alive, barely literate; but as she calmly and silently rolled up your soiled shirts she did something wise and terrible. There was no action in it, no gesture, not even a look, certainly not a caress; there was really nothing, and yet it was a profound and suggestive impertinence. At the time you were aware of nothing but an inexplicable discomfort. You twisted in your chair; your body needed moving and you got up and opened the door for her.

“I’ll come back Friday,” she promised.

It must have been three months later that there happened to be a crowd in your room when she came; by then you were always making sure to have candy for her and to be always there when she arrived. That day you didn’t want to give her the candy with the other fellows present, and without even a glance she somehow let you know that she understood perfectly and sympathized.

When she had gone somebody remarked that it was a pity that so young and delicate a child had to carry bundles around.

“Oh, that little bitch,” said Dick Carr, known as the Mule. “Nothing’s going to hurt her. She’s got a nasty line.”

Two or three protested in the name of innocent childhood. No one seemed to see you trembling.

“You’re nuts.” The Mule spat a rich tobacco brown. “She used to come for my stuff, but I changed over to the Chink. Honest, I was afraid. Hell, Bill, she might seduce you.”

Without willing it you were on your feet and advancing on him. “Carr, you’re a dirty low-down skunk.”

The words weren’t so bad, among friends, but your tone and attitude made them gasp. The Mule, a seasoned halfback with nothing left to prove, was contemptuously surprised but undisturbed.

“My god, you aren’t tilting your little lance for her, are you, Bill?”

Blindly you slapped him in the face and as he leapt out of his chair a dozen restraining hands clutched him. Here of course tradition stepped in, not only of dear old Westover, but also of all the manly centuries. Time and place were discussed and courteously agreed upon. There wasn’t a lot of excitement because it was taken for granted that the Mule would hit you once and then watch you bleed.

It was agreed afterward that no one could adequately describe that encounter. The Mule certainly did hit you and you certainly bled; but long after you were logically extinct, with your face a mass of pulp and your ribs trying to escape by way of your backbone, you still poked your bruised fists somehow at that gigantic shape which must be annihilated before you went down to stay. You were not aware of either weariness or pain, though you did think that surely all the time in the world had been used up. Probably now the Mule could easily have given you the coup de grace, but he seemed to be sick of it. Perhaps aware at last that his real opponent here was something that had no blood to lose, and that to knock you down again was pointless.

You were held, finally, not only from combat but also from falling, while the Mule stood panting, wiping his face with a handkerchief, his undershirt splotched with dirt and blood not all yours; and when you had been half led and half carried back to your room you collapsed utterly. Late that night, too gone to move, you lay and watched your admiring visitors eat the candy you had bought for little Millicent.

Skinny Porter, who is now an actuary for a life insurance company here in New York, said that the battle lasted eighteen minutes, but within a few months the legend had grown to over an hour. At any rate no one had ever before stood up to the Mule for any appreciable time whatever, and you were suddenly famous. Kept in bed for a week, you were visited on the third day by the Mule himself.

“Well, Bill, you old bastard,” he said affectionately.

Not long after that you began to call him Dick instead of Mule, specifically at his own request, and thus became a man of note not only for having stood up to the Mule, but for being chosen as his chief intimate. Whether there was then, or ever, an authentic bond between you is unknowable. As well as you can judge through the jungle of the years, on your part it was probably a smirk at opportunity. He was the most popular athlete of the year, universally liked, even by Old Prune, and he was by far the richest man in the college. Fabulously rich; motor cars for undergraduates were at that time unheard of, but Dick had one. On parties he would flash hundred dollar bills, not offensively; and spend them.

All the spring semester you were inseparable, and when you went home in June you had promised to visit him during the summer. Home was flat. Jane had gone to Europe with one of the early schoolteachers’ crusades for culture; Larry and Margaret and Rose were still floundering in the jelly of childhood; your father and mother were more obviously than ever conveniences of nature. Not that you felt this then. At that time it was still understood that you would go to the College of Pharmacy, and you still contemplated a safe and complacent career in the leading drug store of the growing and bustling Ohio town without real aversion, chiefly perhaps because you saw no alternative. Besides, those few weeks were filled with expectation of the visit to Dick Carr’s home in Cleveland; and Mrs. Davis’s Cleveland address had been in your little red memorandum book for more than a year.

You had not been in Cleveland twenty-four hours before Mrs. Davis was entirely forgotten.

You fairly and visibly trembled with timidity that first afternoon in the garden when Dick introduced you to his sister Erma. Yes, you were always timid with Erma Carr, damn her! Partly perhaps it was the house, the servants, the motor cars, the glistening fountains, the clothes-closets lined with fragrant cedar? Perhaps, but god knows Erma was enough. You see now that you resented her and felt her cold presumption that first day. Then you were charmed and submerged and inexpressibly timid.

By the end of the third week she asked you to marry her. Yes, damn it, she did, though she may have left the question marks to you. How many times you have wondered why Erma picked you, suddenly, like a flamingo darting at a minnow, out of all that were offered to her. It is amusing, your irritated concentration for more than twenty years on that trifling why. Yes, you were handsome after a fashion, with your large and mild but not stupid brown eyes, your diffident and awkward torso and shoulders, your thick tumbled hair that left the line of your head to be guessed at, and your angular, slightly delicate face. Your legs always had, and still have, a free fine swing. That first day, the first hour, Erma told you how well you walked. But none of that answers your question. What caught her was the timidity, not the timidity of a fool or a coward, but of a stag not quite willing to leave the set of his horns to nature and still not heroic enough to adjust them himself.

You were driving with Erma along the lake shore the afternoon the telegram came, and when you returned it was waiting for you: Father very ill come home at once Whateley.

As you hurriedly packed with Erma and Dick standing by sympathetically you suddenly remembered with a shock that Jane was still in Europe. When you got home, after midnight, your father was already dead; had, in fact, been dead at the time the telegram was sent. A greater trial than the bereavement was your mother, in whom a thousand unsuspected springs of suspicion and resentment were suddenly released. She held against you unreasonably and implacably the fact of your absence when your father had breathed his last, and she seemed always to be saying, from breakfast till bedtime, though of course never uttered, “You are not the man to take his place and steer this ship.” Larry, far more masterful than you even then, offered an alliance, but you were too timid for it. Male rule was done in that house.

When Jane came come it was like Napoleon back from Elba. Your mother contentedly retired again into her mist, and from that day faded perceptibly. Margaret and Rose stopped their incessant squealing, and Larry, with a shrug of his shoulders, sought other worlds. With the perfection of tact Jane considered and felt the difficulties of your position, and your mature admiration of her dates from that time.

“You don’t have to decide now whether the drug business is the best thing for you. You’ve got to finish college. I can run the store for a couple of years; it’ll pay better than ever; you’ll see. Please, Bill, you’ve simply got to finish. With some kinds of men it wouldn’t matter, but for you it’s important.”

In a letter you had sent Jane to Paris, from Cleveland, written on the Carrs’ engraved paper, you had said a good deal of Erma; but though Jane asked about her now at length you did not mention the engagement. You felt strongly that the counter of that drug store was the place for you, and the real truth—one of your favorite bits of irony—is that you shrank from so formidable a task! Jane undertook it blithely, as one goes for a walk, and you packed up and went off for your third year.

The knowledge would put out no fires in hell, it would change nothing either in the lost years or the present torture, but what would you not give to know how much of the power pulling you back was the desire to hear little Millicent knock at your door! The thought is entirely too grotesque for any credit, but now you suspect even that.

Only one thing was then in your mind. You had accepted Jane’s generous offer, and you had bowed to the necessity of postponing the fulfillment of your own responsibilities, only because you were going to have a career as an author. You knew that words had always excited you, verses of yours had been published in the local weekly, and in your second year you had been placed on the staff of the college paper. You rejoiced that finally you had had the acumen to perceive to what all this clearly pointed. Famous writers can marry even the wealthiest and most beautiful women without a thank you. Or even refuse to marry them because they have more important business in hand. Of course, under this plan, even if you and Erma did eventually marry (you were thinking that with her it might already have become a hot weather episode), it could not happen for many years. You were twenty-one; she was twenty-three. You could easily write a book a year. By the time you had written eight books (only half of them perhaps outstanding successes), she would be thirty-one and you twenty-nine. That would be all right, provided you hadn’t decided by then that marriage was a mistake anyway.

That winter you did write two or three stories, and one day read one of them to Millicent, with whom you were by now enmeshed in a strange and peccant intimacy. Still you wanted pathetically to call her Millicent, but she wouldn’t have it; Millie she detested; you called her Mil and at the sound of it she flew to you. As you read the story, she sat like a diminutive mother-of-the-world watching her man-child play silly games; when you had finished she said:

“I like it, but I’d rather…”

She was never verbal.

A leap of nearly two years to the next marked and fateful hesitation. You and Dick Carr were seated in a café on Sheriff Street in Cleveland, having just come in from a ball game. Dick was proceeding with an argument he had been carrying on for a month.

“I can’t understand why you don’t see it, Bill. It’s so obviously the thing to do.”

“It would mean giving up my writing,” you protested for the hundredth time. You had had two stories published in a Chicago magazine. At the title of the first one, when it appeared in print, you had stared for a total of days; you had kept the magazine open so you could see it while you were dressing, and you can see it yet, in large black type:

THE DANCE AT THE LAZY YbyWilliam Barton Sidney

“Hell, that game isn’t worth a damn, I think you can really do it, but it isn’t worth a damn. If you do it for money there’s not really much in it, and if you don’t do it for money what the hell do you do it for? Anyway, I’m asking this more for my sake than for yours. I’m over twenty-one now, and I’m going to be the works down on Pearl Street all right, but I want you along. If Dad hadn’t died when I was a kid I suppose I’d be going to Yale or taking up polo, but that’s out. I see where the real fight is, and I’m going to be in it.”

“You don’t have to fight so hard, do you, if you’re worth five million dollars?”

“You bet you do. Old Layton at the bank told me yesterday that the business has been going back for two years. He said young blood was needed. Right. I’ve got it. So have you. Of course I’m dumb as hell but I’ll catch on and then watch the sparks fly. There’s going to be the devil to pay when I start firing those old birds down there about a year from Thursday. I want you in on it, Bill. It may be a real battle, but that’s all right. I know you don’t mind a fight.”

Oh. That. Dick was prouder than you of the Battling Bill legend at Westover, perhaps with better reason. Your silence encouraged him to go into other details.

“The set-up down there is that I own half the stock and Erma owns the other half. She’s more than willing to let me run the thing provided her dividend checks come along. I’m going to be elected to the Board, and President of the company at the meeting next week. What I want to do is get the whole thing right in my fist. I’m going to spend most of the winter in the plant at Carrton, and meanwhile you’ll be picking up all you can here at the office. You can start in at any figure you want within reason—say five thousand a year. Later you can have any damn title there is except mine. You can trust me to come through when the time comes.”

In his brusque and eager sentences, Dick was already the Richard M. Carr who is new on forty directorates. And already he was saying within reason—but that’s unfair for his offer was generous and uncalculating: A hundred dollars a week was to you affluence. You should have accepted it quickly and eagerly and confidently. Or you should have said “Start me in at two thousand, though I can’t earn even that at first. When I’m worth more I’ll take it fast enough.” Or you should have refused: “No, Dick, I know I can write and I’m going to do it, but for god’s sake invite me to visit you now and then for I’ll probably need a good meal.” Or you should—oh hell. The five thousand coaxed you onto another bridge you weren’t sure of.

And yet none of the bridges has ever really collapsed—not till now, not till this moment.

It was like Erma never again to have mentioned the garden episode. Either you could see that she had changed her mind or you were too stupid to bother with. At the time of her first trip to Europe she probably still intended to take you eventually—possibly not. One of your longest sustained curiosities was to see that unlikely husband of hers, whom she claimed to have picked up in a fit of absentmindedness on a beach somewhere east of Marseilles. The winter they spent in New York you were not yet there.

Did you or did you not marry Erma because you saw conscription coming and wanted to escape it? As Treasurer of the Carr Corporation, one of the big metal industries of the country, you could certainly have been exempted anyhow; there is too the fact that you were genuinely tempted to enter the army notwithstanding. There is of course one other explanation of that reluctant venture, that it might be desirable for the salaried treasurer of the Carr Corporation to be married to half of its stock.

You are determined to grant nothing to the loveliness and fascination of Erma herself, and yet she was lovely enough as she unexpectedly opened the door of your private office in New York that December morning. Off came her hat, as it did invariably under all possible circumstances, allowing the clipped ends of her fine yellow hair to fall on either side of her face. Her dear pink skin glowed with its perpetual nervous excitement. You had not seen her for nearly three years.

“Here I am—isn’t it silly? To come back from Provençe at this time of year! I must be getting old, I honestly think it was the thought of Christmas that brought me. Last year it was terrible, at Tunis—Pierre had hives or something and couldn’t eat anything but cheese. I’m so sorry Dick’s out of town—they just told me. How do you like having the office in New York? My, but you look up to almost anything! Really elegant!”

Now, of course, you would never see the unlikely Pierre, since he had died the preceding spring, somewhere around the Mediterranean, possibly in the middle of it. Erma’s infrequent letters, which Dick would usually give you to read, were never very precise. He had handed you this one at lunch one day and when you had finished reading had said with a grin:

“Now why don’t you and Sis go through with that little affair you started in Cleveland once?”

You had never known before whether Dick knew.

It became apparent that Erma did intend to go through with that little affair. She had not been in New York a week before she told you that she was “fed up with that ’sieu-dame stuff,” and it may have been as simple as that, but that did not explain why she again selected you. By that time you had become much more articulate than in the day of the famous garden scene in Cleveland, and on the morning that she made the announcement, across the breakfast table, you put it up to her squarely.

“I haven’t the faintest idea,” she replied brightly. “Do you mean that you feel yourself unworthy of me?”

“I’m not making conversation,” you said.

“Oh. Well. Ask the flower why it opens to the bee, or if you prefer, the lady-salmon why she swims a thousand miles to that particular creek. If she’s properly brought up she’ll tell you, but it won’t be true.”

“I don’t believe it’s that kind of a reason. I honestly can’t imagine what it is.”

It took only a little of that to irritate her, and no wonder; you were never a greater fool. To end the argument she took things into her own hands, and the following autumn there was an effective climax to what the newspapers called a youthful romance. This whole thing had been consummated without your having reached a decision of any kind. That seems preposterous, but it is literally true. You never agreed to marry her; you never decided to marry her. That was worse than timidity; it was the act, or rather the passivity, of an imbecile.

If in that passivity you unconsciously had your eye squinted at a more solid footing in the unreal world you inhabited, you had your trouble for your pains. Erma’s stock has remained in her vault to this day; and tonight, and tomorrow (oh yes, there will be a tomorrow) you will still be the salaried treasurer. Forty thousand a year. Erma pays sixty thousand rent for the place you and she call home. Twenty thousand a year you save. The six cars in the garage were all bought by Erma, though there is another she doesn’t know about. Over two hundred and fifty thousand you now have in your own vault, by god! Erma pays the servants, fifteen of them, not counting the country. Last year her dividends—oh hell! Once started this sort of thing can go on forever, as you’ve discovered before. Essentially you don’t care a hang about money anyhow. You would certainly be hard put to prove it, but it’s seriously quite true.

There was one other time when you might have got the thing in your fist, as Dick says. One other time…that evening about a year ago…it would not then have been too late…but there is so much bitterness concealed here that when you think of it you must take care to do so with the utmost calmness and restraint, otherwise you would lose your last and only friend and be within reach of insanity.

This is scarcely the picture of a man who would execute a desperate and hopeless enterprise. What are you doing making another gesture in a last effort to impress yourself? She doesn’t believe in it, and she knows you far better than you know yourself. Last night she said:

“I’m afraid well enough. But not that you’ll hurt me that way. Call it contempt, it doesn’t matter what you call it. There’s nothing in you that makes you get even with people. Don’t ask me again what we’re going to do, as if we were two wheels on a cart. We’ve been fitted for what we’ve done together, but I’ve been me and you’ve been you. There’s nothing changed now if you don’t bring words into it. You know I have always lied to you and always will. It isn’t the truth you look for in me.”

That is the longest speech you have ever heard her make. When at its end her eloquent hand lifted a little and her eyes softened and faintly offered to close, you stumbled back as if in terror of your own threats. She let her hand fall and smiled a patient assurance.

“Come back tomorrow night.”

B

Not halfway up the first flight, he stopped and listened. That was the basement street door closing. Mrs. Jordan putting out the milk bottles. He almost called to her. She would have called back, what d’ye want, in a tone that advised him to want as little as possible.

His right hand left his overcoat pocket and took hold of the rail; when it left the handle of the revolver it felt as if it were letting go of something sticky and very warm. The wires hummed and buzzed in his head.

II

Just what is it you expect to accomplish? One of your favorite and best-articulated beliefs is the futility of anything we may do to other people. The things that are done to us are the only ones that matter, especially the things we do to ourselves. Of course our own acts mostly have a rebound, but not this fatal act you are now considering, knowing all the while that it cannot be consummated.

All the futility of Jane’s thrusts at you, for instance, did not arise from your antagonism and parade of independence. The futility was inherent in the material she was trying to work with. The question of motive need not enter. What considerations moved her are entirely beside the point as far as you are concerned.

The fact is that she is the woman for you. This is true in spite of society’s traditional attitude, first brought to you the day that red-haired boy (whose name you have forgotten) taunted you with being tied to your sister’s apron strings. And later shouted at you incessantly from across the street until the shocked neighbors made an issue of it:

“He drinks his sister’s milk, he drinks his sister’s milk, he drinks his sister’s milk!”

Very well, tied to your sister’s apron strings. That is worse then than being tied to the ribbons of Erma’s rue de la Paix robe de nuit, or chained with steel to the black and impenetrable armor of the woman upstairs? Bah. The world of course is thinking of incest and hasn’t even the courage to say so. The concern is authentic, physiologically, but who is talking of physiology? Not you. You are not responsible for what you may or may not have dreamed as an infant and a boy, but you know what you think as a man, and when you say that Jane is the woman for you, you mean that all the security and peace you have ever known, all the gentle hours of content, all the exciting assurances that the world was made for you too, have come from the touch of her hand and the sound of her voice. Anyone who tries to translate that into that which may be bought at any street corner for two dollars has very little to do.

But you’ve never thanked her for it, and it has always been futile. The time you went home from Cleveland for your things, having definitely agreed with Dick, Jane listened quietly to your grandiose plans and exaggerated enthusiasm, along with the rest of the family. She gave you your father’s old place at table that evening, and you noticed that your mother accepted the arrangement calmly and even with a mild pleasure, because it was Jane’s.

The following morning Jane came into your room while you were packing.

“Bill, I’m afraid you’re being driven into this by your feeling that you’ve got to do something for the family. You shouldn’t, really you shouldn’t. The store’s doing better than ever and I’m honestly having a lot of fun with it. You must come down this afternoon and see all the new stuff I’ve got. The fountain is a peach. I’m only twenty-five, and you don’t need to think I’m going to get covered with moss. The way this town’s growing we can sell the store for a lot of money in a few years.”

You wouldn’t admit anything. Superficially you were offended.

“Gosh, you might think I was taking a job cleaning streets. This is the real thing, Jane. Five thousand a year for a man of my age isn’t to be sneezed at.”

“It’s not your line. I’m glad and proud you’ve got the offer; I suppose it would rush nearly any boy off his feet. But I’m even prouder of that second story you wrote. I think it’s pretty darned good.”

This made you glow, but you protested:

“It was about the twentieth, and most of them were terrible.”

“I mean the second one published. Oh, Bill, don’t let yourself be gobbled up. I expect you think that it’s just that I want to manage things, but it isn’t. If you were older than me it would probably be the other way around. The store can keep all of us nicely. What if you don’t make much for two or three years, or even five?”

Futile. In your pocket was the five hundred dollars Dick had advanced, more than you had ever seen before. Most of it went to pay off ancient personal debts around town of which even Jane knew nothing.

She tried again four years later, when the store was sold and you went down to help take the sucker off the hook as Jane put it in her letter. In reality there was nothing for you to do but sign papers; Jane had made an impeccable deal. She was now mature, in full flower, radiant and assured. Her own future was perfectly indefinite, but not with the mist of doubt or hesitation.

“I’m going to New York and take Rose and Margaret along. Mother wants to stay here with Aunt Cora. Thanks to your generosity Larry can go to college next month without anything to worry about.”

As neat as that. The talk you had with Jane that night was the closest you and she had ever got to each other. You admitted your regrets and she appealed to you with tears in her lovely eyes. You longed inexpressibly to say:

“Take me to New York with you. Let’s be together. There’s no one but you anywhere that’s worth a damn. I’ll write or I’ll get a job or I’ll do anything. Maybe some day you will be proud of me.”

Well why not? Tied to your sister’s apron strings. No not entirely that. Drawn as you were to her, you were at the same time repulsed. Surrounding that seductive haven were difficult and dangerous shoals. Perhaps underneath all her tact and competence and beautiful strength you felt an avidity of power which would at length leave you a naked and pendent slave of her compassion and her will. Or perhaps it was something much less elaborate; some feeling deeper than anything you have words or thoughts for.

At any rate it was again futile. When you departed for Cleveland the next day everyone but Larry was in tears; this was different from other departures; it was the beginning of the end of the roof and that family.

Even more to the point by way of futility have been your own efforts at Larry. They have affected him of course in superficialities such as his place of being, his momentary companions and his intellectual opinions; once he even willingly followed your advice regarding the choice of a suit and you can’t get closer to a man than his clothes. But in no essential have you left a mark on him.

How differently from you did he pass from the morning twilight of college into the bright day. He bounded out of the west into New York like a calf confidently and arrogantly bumping its mother for a meal. This was only a week or so after Erma had returned from Europe widowed of the unlikely Pierre, and you had just had lunch with her. Larry was pleasantly impressed but not at all overawed by your elaborate office. Almost at once he was telling you that he had never properly thanked you for putting him through college, that he was really tremendously grateful, that he would pay you back as soon as he could, and that he was glad it was over.

“It’s mostly horseplay. They don’t really know any of the stuff they tell you, except football. That’s the only thing they’ve found out for themselves. I’m glad it’s over. Have you decided where I’m to start blowing up the buildings?”

He was leaving it all to you, and you were thrilled by this, unaware that it was only because to his youthful eagerness and ardor details were unimportant Also it had already been decided. Dick had been extremely decent about it, regretting that he hadn’t a younger brother of his own to start along the line, and welcoming Larry as a substitute.

He spent six months in the plant in Ohio, six more in the Michigan ore mines, some few weeks in New York, and then was suddenly interrupted by the war.

Larry’s letters to you and Jane were your only intimate contact with the insane ultimate consumers of the steel and iron toys which were causing the stock in Erma’s vault to increase in value at the rate of six thousand dollars a day. Being treasurer of the corporation, you were in a position to contemplate that insolent accretion with fitting ironic admiration. But for the censor Larry’s narratives from the trenches would have served excellently as frontispieces for the imposing rows of journals and ledgers which were locked each evening behind those massive steel doors on lower Broadway.

Back as a decorated captain, Larry returned to his desk as if nothing had happened. It was easy to see in his eyes the questions that had not been there before, but he left you to guess at them. Was that true of Jane also? You wonder about Larry and Jane.

He proved himself, young as he was he rose in importance by his own ability and force, but during all those months that became years you felt a vague uneasiness about him. All the time you wondered what it was and why it disturbed you so, not aware of the deep significance which his presence and progress in that environment had come to hold for you, as vindication of your own acceptance of it.

The explosion came at a difficult moment, and unexpectedly. Only the previous week Larry had won new laurels by bringing to a successful close the Cumberland bridge negotiations, down in Maryland. You had heard Dick offer him praise of a different character from any you had ever earned. The difficulty though had come through Erma, whose pretty teeth had shown themselves for the first time the night before in a most inelegant snarl. You didn’t feel like lunching with anyone and were annoyed at Larry’s persistence. When, immediately after you and he had been seated at the usual corner table in the Manufacturers’ Club, he announced that he was going to leave the Carr Corporation, you were at first merely irritated, as if he had said he was going to put a fly in your soup.

“Of course you don’t mean it. What’s the joke?”

“There’s no joke. I’m going to chuck it.”

“But good heavens, you’re crazy. What’s the matter? What’s the idea?”

Larry took a drink of water and unfolded his napkin. He looked uncomfortable.

“This is the only hard part of it, Bill, trying to tell you why. You’ve been so damn good to me and from your standpoint this must seem insane. I’m afraid I can’t even be very definite about it. Only it’s not the life for me. It’s not what I want to do. I suppose I’ll get into a rut no matter what I do—everyone seems to nowadays—but this is the wrong kind of a rut.”

“You might have found that out seven years ago, before Dick and I took all the trouble we’ve taken, and made room for you—”

“I know it. I know all you’ve done. But my mind wasn’t made up till quite recently. At that I don’t think I owe the company anything. If I could only tell you exactly how I feel about it, Bill, I think you’d understand. You certainly have a knack of understanding people.”

He went on explaining with words that explained nothing while you scarcely heard. You were filled with anger and even with a sort of terror which you now comprehend much better than you did then. There was indeed nothing trivial about this; it was a major and almost a vital casualty for you; it meant that Larry was spewing out in disgust that which you found no great difficulty in swallowing and digesting. Essentially that was what it meant, and it threw you almost into a panic. You had often suspected yourself of a finer nature, too fine to be really comfortable in this den of hyenas, but not Larry. It was intolerable.

There he sat, for all his expressions of gratitude and regret and his embarrassed concern for your feelings really quite imperturbable. Unshakable. You asked him with a sneer:

“What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. I’ve got a good deal saved, thanks to your and Dick’s generosity, and I may buy the Martin place out in Idaho where I went last summer. He’ll sell cheap.”

“Going to raise cattle?”

“Perhaps. Or get a job in the forest service. I don’t know.”

Evidently he had been considering it for some time.

That evening you went to see Jane, at the house on Tenth Street where you always felt incongruous, like a pig on a silk cushion, despite Jane’s presence. You were recurrently indignant at that feeling and tried to bully yourself out of it. What the deuce, you yourself were not precisely illiterate; you read Norman Douglas and Lytton Strachey and went to the concerts of the International Composers Guild. But in this Tenth Street intellectual sea you swam with difficulty, or more commonly stayed behind on the shore, for they were always beyond your depth almost before they started; you listened to their jargon with uneasy contempt, and loathed Jane when she undertook to explain to you who Pavlov was. Your visits had become more and more infrequent.

This evening you expected to find there the usual crowd, Jane’s husband (if he were not away lecturing on god knows what), a writer or two, at least one experimental actress and an assortment of parlor radicals. You intended to take Jane off somewhere and persuade her to bring Larry to his senses. But when you arrived the rooms on the ground floor were dark, and proceeding brusquely upstairs, past the faintly protesting maid who had let you in, you found Jane and Larry alone in Jane’s room.

Larry was as startled at your sudden appearance as though you had caught him rifling your desk. Jane seemed merely glad to see you.

“Bill! It’s almost a family reunion.”

In the six hours since lunch you had somewhat recovered your balance, and for that matter you did not yet suspect the depth of this wound; so you went to look at the baby with proper appreciation and waited till you had all gone downstairs before you remarked:

“I suppose Larry’s told you of his contemplated renascence.”

“Yes. Oh yes.”

“We’ve just been talking about it,” Larry said. “Jane thinks it’s all right.”

“So it’s a conspiracy.”

“Not actionable.” Jane came and sat on the arm of your chair and put her hand on yours. “Don’t cut up about it, Bill, there’s a dear.”

“It would make a lot of difference if I did. I think it’s crazy and I think it’s a pretty rotten way to act. After all I’ve done…”

“What have you done?” But instantly Larry’s voice changed. “I don’t mean that. I mean you might think I was letting you down. Good lord, I’m of no importance down there. You’ve got dozens as good as I am.”

“We’ve not got dozens who have your opportunities and your future. And who prepared it and made it easy? Oh, I know you’ve worked and you’ve made good. Quite probably you’ll prove to be a better man than me, but that isn’t what gave you the inside track.”

Larry opened his mouth and closed it again. Jane, whose hand had remained on yours, rose suddenly and went to him.

“You run away, Larry, and let Bill and me talk. Please. Go on.”

He went, observing that he would see you in the morning at the office. Jane came back to your chair.

“Meaning that you’ll smooth out my childish irritation,” you observed.

“Yes,” she agreed unexpectedly, putting her hand again on yours. “Only I don’t know how childish it is. It’s a darned shame.”

“That I’m so unreasonable, I suppose.”

“Oh don’t do that, Bill. It’s not a question of anyone’s being unreasonable. This was bound to hurt you. I told Larry so the first time he spoke to me about it, and at the same time I told him I approved.”

“So it’s been cooking for a long while. I like the picture of you and Larry calculating the chances of my eventual recovery.”