Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

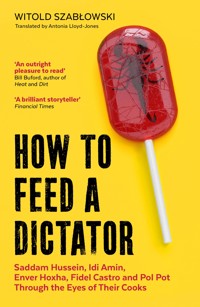

A devastatingly original look at the world's worst dictators, through the eyes of their personal chefs, by award-winning Polish author Witold Szablowski. What is it like to cook for the most dangerous men in the world? In this darkly funny and fascinating book, Witold Szablowski travels across four continents in search of the personal chefs of five dictators. From the savannahs of Kenya to the faded glamour of Havana, and the bombed-out streets of Baghdad, Szablowski finds the men and women who cooked fish soup for Saddam Hussein, roasted goat for Idi Amin and chopped papaya salad for Pol Pot. He reveals the strangeness of a job where a single culinary mistake could be fatal, but a well-seasoned dish could change your life. And in doing so, he lifts the veil on what life is like at the very heart of power.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 360

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

v

Menu

ix

If “we are what we eat,” cooks have not just made our meals, but have also made us. They have shaped our social networks, our technologies, arts and religions. Cooks deserve to have their story told often and well.

—Michael Symons,

A History of Cooks and Cooking

Map

Starter

Knife and fork in hand? Napkin on your lap?

Ready or not, please be patient for just a while longer. First there’s going to be a short introduction.

Before we move on to the main menu, I’ll tell you the story of how I almost became a cook myself. In my early twenties, I had just graduated from university when I went to see some friends in Copenhagen. One thing led to another, and a few days later I found a job there washing the dishes at a Mexican restaurant in the city centre. It was under the table, of course, but in four days I earned as much as my mum did in an entire month as a teacher in Poland. That helped me to tolerate the burned fat, the smell of which I could never wash out of my clothes or skin, and the crappy decor. At our restaurant you were constantly tripping over a cactus, and on the walls there were fake Colt holsters and sombreros on hooks, which at least one of the tequila-sodden customers would try to steal every single night. The way into the dining area was through xivsaloon doors that were straight out of a Western; the kitchen was the only space with doors that could be closed.

And a good thing, too. Better for the clients not to know what went on in there.

There, over the cooking pots, cigarettes dangling from their lips, stood the chefs—all of them from Iraqi Kurdistan. They’d been drafted in by the owner, an Arab, who cruised about town in a swanky new BMW. He’d bought the place from an ageing Canadian who’d grown tired of owning a Mexican restaurant in Copenhagen. I don’t know how much he paid for it, but business was booming.

There were six chefs in total, and they all had their hands full from dawn to dusk. None of them had ever been to Mexico, and I suspect that if you’d handed them a map, they’d have had trouble pointing it out. I don’t think any of them had ever been a chef before, either. But they were taught how to make burritos and fajitas, how to fry chicken Mexican-style, and how to add a small squirt of sauce to the tacos in a way that made it look as if they’d added lots. So they worked away, frying and squirting. The customers loved the food, and that was all that mattered. “There’s no work in Iraq,” the chefs would tell me, as if they had to explain themselves.

They taught me to smoke marijuana before starting work. “Otherwise it’s unbearable,” they’d say as they blew out smoke. They taught me to count to ten in Kurdish. They also taught me a few swear words, including the rudest one, which had something to do with your mother.

I spent the entire day working three dishwashing machines and scraping burned chicken out of the large pots by hand. In the rare spare moment, I tried to tame a rat that lived on the garbage heap by offering him scraps; I got this stupid idea from a movie. Luckily, the rat was cleverer than I was and wisely kept his distance.xv

The Kurds were great co-workers; they planned my future career for me. “We’ll teach you to cook,” they promised. “You won’t have to wash dishes all your life.”

That’s what I, too, was hoping. So I learned to make burritos, fry chicken, and squirt sauce on the tacos exactly as they did.

Until one day my mobile phone rang. Someone had told the owner of another restaurant about the guy who was willing to work off the books. The other owner wanted to make me a better offer. This time I’d get as much as my teacher mum in Poland earned in a month in three days instead of four. Plus I’d be promoted to assistant cook. Without a second thought I said adios to the Kurds. Two days later I was putting on a black apron and taking up my post by the gas stove in a small but popular restaurant just off Nørrebrogade, one of the city’s main arteries. This time there were two of us manning the kitchen: the owner, whose name was August, and me, Witold, his assistant.

August was half-Cuban and half-Polish, but he’d been raised in Chicago and didn’t know a word of either Spanish or Polish. He’d spent most of his life working as a cook on cargo ships. The restaurant was meant to provide his pension.

Until the clients appeared, you could talk to August quite normally, but as soon as the lunch hour came—and out of our eight tables, let’s say six were occupied—the devil got into him. The pans would rattle, the plates would fly, and August would scream. He’d hurl vulgar abuse at all his staff, with his wife bearing the brunt of it; she ran the bar and was also his business partner.

“August,” I finally declared, after the latest of these outbursts, “if you speak to me that way once more, I’ll fling my apron to the floor and be out of here.”

August just smiled.xvi

“Witold, I’ve worked in the kitchen all my life. I know who I can and cannot shout at.” Seeing the amazed look on my face, he added, “We work together all day long, just the two of us, in forty square feet. I may yell at you, but you’re the last person I want to pick a fight with.”

So his fury was controlled! At that point it occurred to me that he could have been a diplomat just as well as a cook. It was the first time I’d seen how crafty and cunning chefs can be.

Once the situation in the dining room settled down, August’s blood pressure would come down too. Then he’d tell stories about the sea; he’d spent half his life there, and he missed it. His tales were full of dolphins, whales, storms, and solitary yachtsmen whom he’d passed in his huge ship. There were tropical islands and frozen Greenland; the whole world was there. When we were free from customers, August became a wonderful, warm, intelligent guy with a great sense of humour. Then the diners would come back, and he’d go nuts again.

I observed his mood swings for several months. Every day we cooked together, and I helped him to come up with the dishes for a new menu. It was like magic: I felt as if we were painting the Mona Lisa together. One day August chilled a bottle of the strong stuff. We sat in the kitchen until late at night, while I chopped the vegetables and meat, and he used them to make ever more fanciful creations.

But there the comparison with painting ends. Leonardo didn’t have to paint his Mona Lisa over and over again, seven days a week, but we churned out the dishes from August’s menu dozens of times a day.

August taught me how to hold a knife without cutting myself and how to take bread out of the oven without burning myself. He xviitaught me to cook steak and how to make salad and a great cream of leek soup. He even taught me what stance to adopt in the kitchen to make it easier to stay on my feet all day.

He also taught me that if there were any fancy fruits left on the plates after the Sunday brunch we were famous for—raspberries, for instance, or lychees, or Cape gooseberries in their papery brown cases—we should give them a rinse and put them on the next customer’s plate.

“They’re too expensive to throw out,” he explained, seeing the horrified look on my face.

Until one day all eight of our tables were occupied in five minutes flat, and there was still a line of people standing in the doorway. August couldn’t keep it in check.

“You fucking idler!” he yelled at me. Evidently, his fury was controlled to only a limited extent. “What are you gaping at? Go get the rolls!”

Too late—my apron was on the floor.

A few days later August called me and even said something that sounded quite like “sorry.” Not that he had any special sympathy for me; I was just a low-cost worker, and it was in his financial interest to get me back.

But I hadn’t the least desire to weather his mood swings again. I got a job driving tourists around Copenhagen in a rickshaw. Six months later I went back to Poland and became a journalist.

But I never forgot how fascinating cooks can be. They’re poets, physicists, doctors, psychologists, and mathematicians all in one. Most of them have an unusual life story; it’s a job where you have to give your all. Not everyone is suited to it, as my own example shows.

For many years as a news reporter, I wrote about social and xviiipolitical issues. I never thought of working as a cook again, though I never stopped being interested in chefs. Then one day I saw a movie by the Slovak-Hungarian director Péter Kerekes called Cooking History. It was about army cooks, and it featured Branko Trbović, who was the personal cook of Marshal Josip Broz Tito, the absolute ruler of Yugoslavia.

He was the first dictator’s chef I’d ever encountered. A lightbulb went on in my head.

I started wondering what the people who cooked at key moments in history might have to say. What was bubbling in the saucepans while the world’s fortunes were in the balance? What did those cooks get a glimpse of as they were making sure the rice didn’t dry out, the milk wasn’t scalded, the chops didn’t burn, or the water for the potatoes didn’t boil over?

Other questions soon occurred to me. What did Saddam Hussein eat after giving the order for tens of thousands of Kurds to be gassed? Didn’t he have a stomach ache? And what was Pol Pot eating while almost two million Cambodians were dying of hunger? What did Fidel Castro dine on while sending the world to the brink of nuclear war? Which of them liked spicy food, and which preferred mild? Who ate a lot, and who just picked at his food? Who wanted his steak rare, and who liked it well done?

And finally, did the food they ate have any effect on their policies? Or did any of their cooks make use of the magic that comes from food to play a role in their country’s history?

I had no choice. There were so many questions to be answered that I had to find the actual chefs who’d cooked for the dictators.

So off I went in search of them.

This book took almost four years to complete, in which time I xixcrossed four continents, from a godforsaken village in the Kenyan savannah to the ruins of ancient Babylon to the Cambodian jungle where the last of the Khmer Rouge were in hiding. I shut myself away in the kitchens of the world’s most unusual chefs. I cooked with them, drank rum with them, and played gin rummy with them. Together we went to the market and haggled over the price of meat and tomatoes. Together we baked fish and bread and made sweet-and-sour soup with added pineapple and goat-meat pilaf.

I had a hard time persuading each of them to talk to me. Some of them had never recovered from the trauma of working for someone who could have killed them at any moment. Some had served their regime loyally and to this day refuse to betray their secrets, even the culinary ones. And some simply didn’t want to dredge up unpleasant memories.

I could write another entire book about how I persuaded them to open up to me. In the most extreme case, it took more than three years. But I managed it. I came to know twentieth-century history as it was seen from the kitchen. I learned how to survive in difficult times. How to feed a madman. How to mother him. And even how a well-timed fart can save the lives of more than a dozen people.

I found out where in the world dictators come from. At a time when, according to a report issued by the American organisation Freedom House, forty-nine countries are ruled by dictators, this is vital information. What’s more, the number keeps rising. Today’s climate favours dictators, and it’s worth knowing all we can about them.

So once again: Knife and fork at the ready? Napkin on your lap? All right, then.

Enjoy your meal.xx

Snack

The first time I saw Brother Pol Pot, I was at a loss for words. I was sitting in his bamboo hut in the middle of the jungle, gazing at him. And I was thinking: what a beautiful man!

What a man!

I was very young then, so don’t be surprised that’s what I was thinking, brother. I was there to report to him on how people were feeling in the villages I’d passed through on my way to his base, and I was waiting for him to speak first. But he didn’t say anything.

Finally, after a long time, he smiled gently at me. And at once I thought, what a beautiful smile he has!

What a smile!

I couldn’t focus on what we were meant to be talking about. Pol Pot was very different from all the men I’d ever met before.

We met in the jungle, at a top secret base for Angkar, the organisation we belonged to. In those days everyone still called Pol Pot Brother Pouk, which in Khmer means “mattress.” For ages I wondered why he had such a strange nickname. I asked several people about it, but no one could tell me. 2

Many months later, one of the comrades explained to me that he was called Mattress because he always did his best to calm things down. He was soft. And that was his strength. When other people argued, he’d stand in the middle and help them to reach an agreement.

It’s true. Even his smile was gentle; Pol Pot was pure goodness.

We had only a very short conversation that time. And when we were done, his adjutant took me to one side and said that Brother Pouk badly needed a cook. He’d had several, but none of them was right for him. So he asked if I’d like to give it a try.

“Yes,” I said, “but I don’t know how to cook.”

“Surely you know how to make sweet-and-sour soup?” asked the adjutant, amazed, because it was the most popular soup in Cambodia.

“Give me a pot,” I said.

And when he took me to the kitchen, I found that I knew perfectly well how to make that soup. You get some Chinese long beans, sweet potato, pumpkin, marrow, melon, pineapple, garlic, some meat—chicken or beef—and eggs. Two or three. You can add tomatoes, too, and lotus roots if you wish. First you boil the chicken, and then you add sugar, salt, and all the vegetables. I’m afraid I can’t tell you how long you have to cook it for, because we didn’t have watches in the jungle and I did everything by feel. I think it’s about half an hour. To finish, you can add some tamarind root.

I also knew how to make papaya salad. You cut the papaya into very small pieces and then add cucumber, tomatoes, green beans, cabbage, morning glory, garlic, and a dash of lemon juice. 3

But the first time I made it, Pol Pot didn’t eat it. Only later was it explained to me that he liked it prepared the Thai way: with dried crab or fish paste and peanuts.

I also knew how to make mango salad, how to bake fish, and how to roast chicken. Clearly as a child I’d watched how my mother did the cooking. Brother Pouk didn’t expect any more than that. I was fit to be his cook.

I went into that kitchen and stayed there until nightfall. I made the lunch, then the supper; then I tidied up and washed the pots and pans.

And that’s how I became Pol Pot’s cook. I was very pleased that I could help. I wanted to stay at the base for the revolution. And for him, gentle Brother Mattress.

Breakfast

Thieves’ Fish Soup

The Story of Abu Ali, Saddam Hussein’s Chef

One day, President Saddam Hussein invited some friends onto his boat. He took along several bodyguards, his secretary, and me, his personal chef, and we set off on a cruise down the river Tigris. It was warm—it was one of the first spring evenings that year. At the time we weren’t at war with anyone, everyone was in a good mood, and Salim, one of the bodyguards, said to me, “Abu Ali, sit down, you’ve got the day off today. The president says he’s going to cook for everyone. He’s going to make koftas for us.”

“A day off …” I smiled, because I knew that in Saddam’s service there were no such words. And because there were going to be koftas, I started getting everything ready for the barbecue. I minced some beef and lamb and mixed them with tomato, onion, and parsley, then put it in the fridge so that it would stick to the skewers well later on. I prepared a bowl for washing one’s hands, lit the fire, baked some pitta bread, and made a tomato and cucumber salad. Only then did I sit down.

In Iraq every man thinks he knows how to barbecue meat. He’s going to do it even if he doesn’t know how. And it was the same with Saddam: people often ate the things he cooked out 8of politeness; after all, you’re not going to tell the president you don’t like the food he has made.

I didn’t like it when he got down to cooking. But that time I thought to myself, “It’s almost impossible to ruin koftas.” If you have the meat ready, you squash it flat onto the skewer, press it with your fingers, then place it on the fire for a few minutes, and it’s done.

The boat set off. Saddam and his friends opened a bottle of whisky, and Salim came into the kitchen for the meat and salad.

I sat and waited to see what would happen next.

Half an hour later, Salim came back carrying a plate of koftas. “The president made some for you too,” he said. I thanked him and said it was very good of the president, broke off a bit of meat, and wrapped it in pitta bread. I tried it and … felt as if I’d burst into flames!

“Water, quick, water!”

I threw a glass of water down my throat, but it didn’t help.

“More water!”

It was no good. I was still on fire. My cheeks and jaw were burning, and there were tears pouring from my eyes.

I was terrified. “Poison?” I thought. “But why? What for? Or maybe someone was trying to poison Saddam, and I’ve eaten it?”

“More water!”

Am I still alive?

“More water.”

I am still alive … So it’s not poison.

But in that case, what was he playing at?

It took me a good quarter of an hour to wash down the spicy flavour.

That was my first encounter with Tabasco sauce. 9

Saddam had been given it by someone as a gift, but because he didn’t like very spicy food, he decided to play a joke by trying it out on his friends. And on his staff. Everyone on the entire boat was running around pouring water down their throat, while Saddam sat and laughed.

Twenty minutes later, Salim came back to ask if I’d liked the food. I was furious, so I said, “If I’d spoiled the meat like that, Saddam would have kicked me in the butt and told me to pay for it.”

He did that sometimes. If he didn’t like the food, he’d make you give back the money. For the meat, the rice, or the fish. “This food is inedible,” he’d say. “You’ve got to pay fifty dinars.”

So that’s what I said, never expecting Salim to repeat it to the president. But when Saddam asked him how I’d reacted, Salim replied, “Abu Ali said that if he’d made something like that, you’d have kicked him in the butt and told him to pay for it.” That’s what he said, in front of all Saddam’s guests.

Saddam sent Salim back again to fetch me.

I was scared. In fact, I was terrified. I had no idea how Saddam was going to react. You did not criticise him. Nobody did that: not the ministers, nor the generals, let alone a cook.

So off I went, terrified, annoyed with Salim for repeating what I’d said and annoyed with myself for mouthing off so stupidly. Saddam and his friends were sitting at the table, on which were the koftas and some open whisky bottles. Some of the guests had red eyes; evidently, they’d eaten the Tabasco-flavoured koftas too.

“I hear you didn’t like my koftas,” said Saddam in a very serious tone. His friends, the bodyguards, the secretary—everyone was looking at me. 10

I was getting more and more afraid. I couldn’t suddenly start praising the food; they’d know I was lying.

I started thinking about my family. Where’s my wife right now? What’s she doing? Are the children home from school yet? I had no idea what might happen. But I wasn’t expecting anything good.

“You didn’t like them,” Saddam said again.

And suddenly he started to laugh.

He laughed and laughed and laughed. Then all the people sitting at the table started laughing too.

Saddam took out fifty dinars, handed them to Salim, and said, “You’re right, Abu Ali, it was too spicy. I’m giving back the money for the meat I wasted. I’ll cook you some more koftas, but without the sauce this time. Would you like that?”

I said yes.

So he cooked me some koftas without any Tabasco. This time they were very good, but I tell you, it’s impossible to ruin koftas.

1.

Wide streets, along which are hundreds of bombed-out houses that haven’t been rebuilt and military checkpoints every few blocks. Canary-yellow cabs flash by, because here Baghdad insists that it’s New York, and every cab must dazzle you with the colour of ripe lemons.

After almost two years of searching, my guide and interpreter Hassan has found Saddam Hussein’s last living cook for me. His name is Abu Ali, and for many years he refused to talk to anyone 11about the dictator, because he feared the vengeance of the Americans. It took Hassan a good twelve months to persuade him to talk.

Finally he agreed, but not without imposing conditions: we won’t walk around the city, we won’t cook together, and Hassan and I won’t be able to visit him at home, though that’s what I’d asked for. We’ll just shut ourselves in my hotel room for the next few days; Abu Ali will tell me everything he remembers, and that will be the end of it.

“He’s still afraid,” explains Hassan. “But he’s very keen to help,” he quickly adds. “He’s a good man.”

So we’re waiting for Abu Ali to arrive, and Hassan is boasting that he has escorted journalists from every country, on every front of every Iraqi conflict, from the American invasion to the civil war to the war against ISIS, and none of them has so much as broken a fingernail. To make sure I don’t become the dishonourable exception, Hassan won’t let me even cross the street on my own.

I don’t believe him when he says the city is unsafe: right next to my hotel there’s a Jaguar automobile showroom, and a little farther on, a large shopping mall. The place is swarming with policemen and armed security guards.

“I know everyone’s smiling and friendly,” says Hassan. “But don’t forget that one per cent of them are evil. Truly evil. To them, a solitary journalist from Europe is an easy target. You’re going nowhere, I repeat, nowhere without me. Even together we’re not going anywhere except in a licensed cab.”

And he adds that only a few years ago foreigners here were kidnapped by the dozen. They were usually released as soon as the company that employed them paid a ransom. But not all of them came back. 12

And I am a freelancer. There won’t be anyone to pay for me.

In spite of all that, you can’t cheat nature. I’m simply not capable of sitting still, so as soon as Hassan goes home to his wife, I slip out for an evening stroll around the district where I’m staying. I pass a few mosques, some clothing stores, and people selling mazgouf, a local fish, which they bake on huge bonfires. I go into a nearby café for ice cream. I talk to a man selling sheep; he breeds them specially for the end of Ramadan, the holy month of fasting. I behave just as I would in any other country, on any other trip. Hassan shouldn’t exaggerate, I think to myself.

Late that night I go back to the hotel and spend a long time writing up my impressions of my walk. I go to bed well after midnight.

Two hours later I’m woken by a tremendous bang. Soon after that I hear sirens. The lights and the Wi-Fi in my hotel are out.

Not until morning do I learn that a few hundred yards from my hotel a suicide bomber has killed more than thirty people.

2.

The next day Hassan is more than two hours late. Following the attack, police control has been tightened throughout the city, and as a result the traffic is frightful. Luckily, Abu Ali’s late as well. We’re waiting for him in the hotel lobby.

“This life is ghastly. You never know when and where the next bomb will go off,” says my guide, sighing. “Since Saddam was deposed, everything’s been plunged into chaos. Lots of the former army officers and secret policemen have joined paramilitary groups, and eventually ISIS. Now the Islamic State is weak, but only just over a year ago it looked likely to threaten Baghdad.” 13

Many of the cities in Iraq are off-limits. I wanted to see Tikrit, for example, where Saddam was raised, but Hassan warns me that it’s very dangerous.

“You have to have a guide who’ll pay the hit squads that control the city,” he says. “But even then there can be problems.”

We’re interrupted by Abu Ali’s arrival. A jacket over a turtleneck. White hair, a small paunch, and an extremely amiable smile. We greet each other Iraqi-style: a handshake and a kiss on both cheeks. It flashes through my mind that for years, the hand I’m shaking fed one of the twentieth century’s most notorious dictators. But we haven’t the time to celebrate this moment. Abu Ali is uneasy. He doesn’t want anyone to see him giving an interview or to ask who he is, for a foreigner to be recording a conversation with him. So we go and get a large jug of fresh orange juice, some water, an ashtray, and some snacks. Then we take the elevator to the third floor, and there we draw the curtains. I switch on the Dictaphone.

I was born in Hillah, not far from the ruins of ancient Babylon, but when I was a teenager, my parents moved to Baghdad, where my father opened a small grocery store, and one of his brothers, whose name was Abbas, opened a restaurant. The restaurant wasn’t far from our house, so I used to go there almost every day. I liked the place, and when I was about fifteen or sixteen, I asked Abbas if he’d give me a job there.

Abbas put me in the kitchen. I learned to make the most typical Iraqi dishes, including shish kebab, kubbah, dolma, and pacha. Shish kebab is pieces of meat marinated in garlic and other seasonings, grilled on the fire, and served with rice or in a sandwich. Kubbah is meatballs made with 14tomatoes and bulgur wheat, served in a soup. Dolma is meat mixed with rice and wrapped in a vine leaf. Pacha is a delicacy—a soup made from a sheep’s head, with its trotters and parts of its stomach added. You boil each of these items separately. You must cleanse them carefully, now and then skimming off the fat and the scraps that float to the surface. You use the skin of the stomach to make a little pocket, which you stuff with finely diced pieces of meat. You cook the pacha on a very slow flame, with hardly any seasoning, at most a little pepper, salt, lemon juice, and vinegar. Finally, you mix the three broths produced by boiling the head, trotters, and stomach, add the pocket stuffed with meat, and it’s ready to serve. The greatest delicacy are the eyes.

My cooking was very successful. The customers liked me, and I liked my work. But after a few years I realised there was nothing more for me to learn at my uncle’s restaurant, nor was I ever going to earn more there. I wanted to buy a car. So I decided to get a new job.

I read in a newspaper that the Baghdad Medical Centre, the city’s largest hospital, was looking for a chef. I applied. At the interview, they asked me only one question: Did I know how to cook rice for three hundred people?

Did I know how? I’d been doing it every day for the past eight years!

I was hired. I bought a car, but after a few years in the job that stopped being enough for me too. I started looking around for something different. I found a well-paid position at a five-star hotel and was just about to start when suddenly I was called up for the army. 15

I found myself in Erbil, a city in the north of Iraq, where the population are all Kurds. At the time they were staging an uprising, led by Mullah Mustafa, one of their top leaders.

Instead of starting a new job at a hotel, I went to war.

3.

The fighting against the Kurds took place mainly in the mountains. I was sent there with a rifle. I wasn’t happy about it. I was twenty-six years old, I had nothing against the Kurds, and I certainly didn’t want to get killed in a war against them.

So I told my commanding officer that in Baghdad I’d been a cook and that I was far better at cooking than shooting. They had thousands of soldiers but not many good cooks. The officer spoke to another officer, who spoke to someone else, until it turned out that Mohammed Marai, one of the commanders, had been complaining about the food. He didn’t have a chef, and an adjutant was cooking for him.

Marai immediately ordered me to come and see him at the front. He had major problems with supplies: the peasants had abandoned their villages, and there was nowhere to get food.

So every day, while our men were fighting the Kurds, I got in a car and drove to Erbil—two hours each way—because that was the only place where you could buy anything. It was very dangerous. The Kurds could have fired at me at any moment.

Cooking something that tasted good on a field stove was close to impossible. I struggled for several weeks, until I timidly asked Marai if I could live in Erbil and cook normal meals there, in a normal kitchen, and bring them out to the front.

Marai agreed that it was a very good idea. 16

So I moved to Erbil, and every day a driver took me to the front and back. I’d pour Marai some soup, serve him salad, heat up the meat, and sit outside the tent—often with bullets flying past overhead. Was I afraid? No. You get used to the idea that you could die at any moment. You focus on where to get a chicken or a fish for the next meal, rather than on death.

Until one day my military service was over. I said goodbye to Marai and the rest, and then I was taken in an army car to Mosul. From there I caught a train back to Baghdad. Just like that. You board a train, and you come home from the war. It was extraordinary, and many years later, when I was already working for Saddam, I was still amazed that we could get into a car in safe Baghdad and a few hours later be in a war zone, where people were being killed.

Unfortunately, there was no job at the hotel waiting for me. But one of Marai’s adjutants suggested to me that if I wanted to work at a hotel, I should apply to the Ministry of Tourism. “They employ cooks for all the government hotels throughout the country,” he said, and gave the name of a friend of his who’d be able to help me.

And that was how, only two months after the war, I ended up at one of the government palaces—the Palace of Peace—taking a special course for chefs.

4.

Navarin is a dish of lamb with cherry tomatoes and potatoes boiled in broth. It’s delicious. I can still remember the day when one of the teachers showed us how it’s made. It was a great discovery—that you can cook lamb, our national meat, 17in a different way, not just by the only method I had known about before.

There were two teachers, John from England and Salah from Lebanon. John taught us about meat and European cuisine, and Salah taught us to make desserts and Arab cuisine. We learned how to make chicken roulade, chocolate mousse, sponge cake, and quiche.

I completed the course with the highest grade of all the students. Instead of sending me to a hotel, which was my dream, the teachers said it would be better for me to stay at the school and teach introductory classes for the next group of students. I also worked as a cook for the Ministry of Tourism.

I ended up on a team that included the best cooks in Iraq. We worked for all the official delegations: government ministers, parliament leaders, presidents, and kings. The king of Jordan came on an official visit, and soon after the king of Morocco came too. I was very excited, because until then I’d only cooked at the hospital, at the front, and at my uncle Abbas’s restaurant. I could hardly have expected to progress from working at those places to cooking for kings!

But often I had no idea whom I was cooking for. Being a cook is a bit like being in the army: better not think too much; just carry out the orders.

Until one day my colleague, whose name was Nisa, and I were given an unusual task: our bosses told us to make the finest cake we possibly could. We worked on it for two days and two nights. We joined sponge cakes with cream to make a square, each side of which was six feet long. Then we made a vertical structure, nine feet high. And onto this frame we built ancient Mesopotamia. We carved the old ruins out of 18sponge cake and made rivers out of marzipan, as well as trees, palms, and animals out of fruit. We decorated the top with an almond flower, and right at the centre we made a waterfall out of coconut shavings.

Two days later we saw our cake on television.

And there, cutting it himself, was President Saddam Hussein. It was his birthday cake.

5.

While we’re waiting for our next meeting with Abu Ali, Hassan kills time by telling me about aliens.

“You can laugh, I’m used to people not believing me. But they really do exist. And they really are interested in us. They fly here to watch us. I am one of very few people who can see them. At every battlefield I’ve been to, I’ve seen them standing off to one side, watching what we’re doing.”

“Are they friendly?” I ask sceptically, because I have to ask something.

“Yes. They know I can see them. They saved my life several times. They feel for us. They don’t want us to get killed or to kill each other.”

It crosses my mind that someone could write a great story about this man who has seen so much evil that in order to get his head around it, he has started seeing aliens. But I’m soon reproaching myself: maybe he really does see them, and it’s just me, with my stupid rationality, who refuses to believe him. From now on I agree with Hassan, whatever he says.

But I’m not here to learn about aliens. So I say, “Tell me about Saddam.” 19

“He was a real son of a bitch,” he says, shaking his head. “He was born near Tikrit, and that has always been a city of thieves and smugglers. They’ve always been proud that the great Arab leader Saladin was born in their city too. Saddam was raised to worship him, and he probably had too much faith in the idea that he was the next leader of the Islamic world. Maybe that’s why he ended up as he did: whatever was going on, he believed that Allah was guiding him. But even so, his career was incredible. His father abandoned his mother when she was pregnant. In an Iraqi village, where to this day medieval rules apply, that must have been very hard for them.”

Saddam Hussein’s biographers would agree with Hassan: from the start of his life Saddam had to be the strongest. After her divorce from his father, his mother, Sabha, formed a relationship with a man known as the Liar; apparently, he tried to convince people that he’d been on the pilgrimage to Mecca, though everyone knew it wasn’t true. The Liar wasn’t rich—he had one donkey and two or three sheep—so he thought up a plan for his wife’s son to help him increase his property. Instead of sending the boy to school, he taught him to steal. “There are stories of him stealing chickens and eggs to feed his family, others of him selling watermelon on the train which stopped in Tikrit on its way from Mosul to Baghdad.”*

On top of that, the Liar was always humiliating the boy, forcing him to dance and hitting him for no reason.

Saddam would have ended up as a petty thief if not for his uncle Khairallah Talfah. This well-read, politically minded man from Tikrit took Saddam to live with him, despite having a small flock of children of his own. At his uncle’s house Saddam learned that there was another world beyond the Iraqi village. And although his new 20guardian’s horizons were not particularly broad either—he sympathised with the Nazis and even wrote a pamphlet titled Three Whom God Should Not Have Created: Persians, Jews, and Flies—it was his influence that awakened Saddam’s curiosity about the world.

A few years later, when his uncle was arrested for taking part in an anti-government plot, Saddam had to return to his mother and stepfather. But he had come to regard Khairallah’s children, especially his son Adnan, as his best friends. His uncle had shown him what it meant to have a family.

Saddam would be grateful to him for a long time to come.

6.

It all began quite innocently.

One of the waiters, whose name was Shah Juhani, told me I was to report to a palace on the outskirts of the city, near the airport. He said they had extra work for me there.

I didn’t give it any special thought, because now and then I had an extra commission at the ministry. Sometimes a foreign minister arrived, sometimes an entire delegation, and sometimes we had to make candy for someone’s birthday. So I went along without thinking what they’d require of me this time. Someone let me in through the gate, and someone else checked that I wasn’t carrying a weapon. On the spot I was greeted by a man named Kamel Hana. He shook my hand and said, “Abu Ali, you need to know that I work in President Saddam Hussein’s security. I’m taking you to see him.”

“Sorry?” I said. I thought it was a joke. 21

“I’m taking you to see President Saddam Hussein,” he repeated, very solemnly. “Everything that happens and everything the president says is confidential.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. I’d been working at the ministry for several years, but I’d never met anyone who cooked for the president. How had I suddenly got here?

I had to sign a special confidentiality agreement forbidding me to tell anyone anything about what I would see in Saddam’s house. It said that if I broke this promise, I would incur the penalty of death by hanging.

It all happened at the speed of lightning. Less than ten minutes after I had entered the palace, I was standing in front of Saddam.

Only later did I put the pieces together. About six months earlier, my bosses had asked me to write up a résumé, listing all the people I had ever worked with and the names of my family members. I also had to bring in a certificate from the police stating that I had never been convicted of anything. The police had been to see my father and Abbas and had asked questions about me—what I’m like, whether I can drink without causing trouble or getting into a fight, whether I’d had contact with foreigners, Kurds, or religious radicals or been in trouble with the law. And finally, whether any customers had ever complained that I’d poisoned them. The police had also been to the hospital and talked to my friends.

At the time I thought it was normal procedure; because I was cooking for kings, they had to ask about that sort of thing, in case it turned out I was crazy.

But they were already grooming me to be the president’s chef. It had all been carefully prepared many months in 22advance—except that I’d had no idea about it. Saddam liked things to happen by surprise. Then he had the advantage.

But I didn’t know that yet. That day I suddenly found myself standing before the president.

“So you’re Abu Ali?” he said.

“Yes, Mr. President,” I stammered.

“Excellent. Make me a tikka.”

I bowed and went to the kitchen.

7.

Kamel Hana came to the kitchen with me. It turned out that his father had been Saddam’s chef too; although he was still working, he was about to retire, and I was to replace him. That was to happen a few months from now, but the president’s other cook was sick, and because Hana had already vetted me thoroughly, he’d decided to fast-track my appointment.