10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

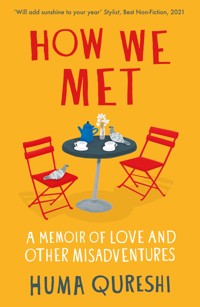

'A Stylist pick for best new non-fiction for 2021'"A beautiful, refreshing and honest memoir about family, love, inheritance and loss" - Nikesh Shukla, author of Brown Baby"A sweet, touching memoir about family, faith and love. There's a purity and simplicity to Huma's writing, as she attempts to reconcile the sprawling weight of expectation with her own desire for a contained but free life. But what does a life on her own terms look like? What even are her own terms? A consolation to others who have trod this very path, enlightening for those of us who haven't, you'll be rooting for not just Huma, but for everyone she loves too." Pandora SykesYou can't choose who you fall in love with, they say.If only it were that simple.Growing up in Walsall in the 1990s, Huma straddled two worlds - school and teenage crushes in one, and the expectations and unwritten rules of her family's south Asian social circle in the other. Reconciling the two was sometimes a tightrope act, but she managed it. Until it came to marriage.Caught between her family's concern to see her safely settled down with someone suitable, her own appetite for adventure and a hopeless devotion to romance honed from Georgette Heyer, she seeks temporary refuge in Paris and imagines a future full of possibility. And then her father has a stroke and everything changes.As Huma learns to focus on herself she begins to realise that searching for a suitor has been masking everything that was wrong in her life: grief for her father, the weight of expectation, and her uncertainty about who she really is. Marriage - arranged or otherwise - can't be the all-consuming purpose of her life. And then she meets someone. Neither Pakistani nor Muslim nor brown, and therefore technically not suitable at all. When your worlds collide, how do you measure one love against another?As much as it is about love, How We Met is also about falling out with and misunderstanding each other, and how sometimes even our closest relationships can feel so far away. Warm, wise and ultimately uplifting, this is a coming-of-age story about what it really means to find 'happy ever after'."This beautiful, romantic memoir grabs you from the first page and won't let you go. Told with heart, wit and quiet restraint, How We Met is the story of how we can transcend the expectations of others and arrange our own happiness in life and in love." - Viv Groskop

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 221

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

‘There are the books that touch you. Then there are the books that open out their arms and straight out hug you – How We Met is this second kind of book. Honest, joyful, at times heart-breaking, at times laugh-out-loud funny, but always generous in its telling . . . this is Huma Qureshi, heart and soul.’

Ami Rao, author of David and Ameena

‘A fearlessly honest memoir of courage, love and loss, and trying to find your place in the world. Quietly heartbreaking but life-affirming too.’

Kia Abdullah, author of Take It Back

‘How We Met is a wonderful read . . . a memoir of grief, becoming and true love. Huma Qureshi is a writer with a sharp eye and a romantic heart.’

Katherine May, author of Wintering

‘How We Met is the book I, and countless women of similar heritage, have been waiting our whole lives for. I cried, and laughed out loud as I recognised myself in so much of Huma Qureshi’s story . . . It’s about being the child of immigrants, it’s about dreams, about motherhood, and it is about familial love, in its many forms. It’s such a beautiful book of quiet confidence, and deserves to be read widely. Huma is a huge talent, and a skilful storyteller with an eye for an exquisite turn of phrase.’

Saima Mir, author of The Khan

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,the photographs, the desperate notes,peel your own image from the mirror.

DEREK WALCOTT‘Love After Love’

For Suffian, Sina and Jude

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR

The past is always remembered differently,depending on who is remembering; this is my version.

THESE DAYS

My six-year-old son Suffian has a friend at school whose parents apparently met on the Piccadilly line on the way to work. Suffian announces this while eating his dinner in the out-of-context way six-yearolds and their ilk are prone to do. ‘Charlie’s parents met on the Piccadilly line and then they got married,’ he says, with knowing authority.

I am sceptical. Things like this don’t actually happen in real life, I tell him.

‘Are you sure?’ I ask.

‘Yes. They met on the Piccadilly line and then they got married. They are the Piccadilly People. Charlie told me,’ he says triumphantly.

The detail, for a six-year-old, is specific (it was definitely the purple line, of that he is certain) so I suppose it might be true. Perhaps Charlie’s parents really do call themselves the Piccadilly People, perhaps they really did meet across a crowded Tube carriage many years ago.

‘That’s nice,’ I say, because it is nice when two people come together in the universe, even if it is in a crowded Tube carriage.

‘What line did you and Dada meet on?’ Suffian asks expectantly. I understand from his hopeful expression that he now believes that everybody’s parents must have met on the Tube. ‘Was it the Northern line?’ he asks, because we live off the Northern line and it is by default his favourite.

‘Ah, so we didn’t meet on the Tube,’ I say, shaking my head.

‘You didn’t?’

‘No. Most people don’t marry people they meet on the Tube. Most people don’t talk on the Tube. Most people don’t even make eye contact on the Tube.’

‘So where did you meet?’ he says.

We’ve never had this sort of conversation before. His curiosity suggests that perhaps he has some sort of understanding that we were people before he and his two younger brothers came along; this feels like a turning point. But right now I don’t know how to answer his simple question because there’s the story of how we met and then there’s my mother’s version of how we met and then there’s everything that happened before and also in between. I don’t know where to begin.

‘Well,’ I say, ‘technically, we met in a coffee shop.’

‘And then you got married?’

‘Not straight away.’

‘After coffee?’

‘No.’

‘But you don’t like coffee.’

‘No.’

‘Then when?’

‘Later. It was . . . complicated.’

‘What does that mean?’

I tell him to finish his dinner.

I text Charlie’s mum. She has no idea what Charlie’s talking about. They met at work.

Sometimes when I’m upset, when things don’t work out the way I had hoped they would, I find myself wanting to gather my children in my arms and hold them close. I tell them that I love them, that I want them to know that they can be whoever they want to be, love whoever they want to love, do whatever they want to do.

My children are still very young and so they aren’t yet embarrassed by such affection, often seeking it out and instigating it themselves. They respond to my fervour with their arms flung tightly and hotly around my neck and I breathe them in the way you do when you don’t want to let someone you love go.

My declarations are randomly announced and often out of context. But somehow it feels urgent for them to know how far my love stretches, no matter how mundane the moment or what we might be doing at the time. It feels urgent for me to say these things, again and again, so that they will always know.

‘You are my sun, you are my moon, you are my earth,’ I say over dinner, pointing to each of their three faces in turn.

‘WE ARE YOUR UNIVERSE!’ four-year old Sina, the middle one, clamours back, punching the air like the superhero he is.

‘I love you to infinity,’ I say at bedtime.

‘INFINITY NEVER ENDS!’ Suffian shrieks. ‘INFINITY GOES ON AND ON AND ON!’ He jumps on the bed.

And so it goes, on and on and on.

Suffian still wants to know how we, his parents, met and now Sina does too. I deflect their questions and ask them instead what they think marriage means. Sina doesn’t know but says he will marry me anyway. Suffian says: ‘It means that you love someone and that when you love someone, it means you’re going to live with them forever.’ He asks me if he’s right; I tell him he is. He tells me he wants to live with me forever. I tell him I’d love that but that I also completely understand if he ever changes his mind.

My friend Saima says: ‘You should write about how you two met. You should write about how it happened.’ I laugh and tell her it’s really not that interesting. Besides, as parents of three small boys all we do is watch Netflix and eat dinner on the sofa once the kids are in bed. ‘But people need to hear that you can break the rules and live happily ever after,’ she says, in earnest. ‘Women, girls like your younger self, they need to know it’s not impossible.’

I laugh it off again. I don’t think of myself as particularly rule-breaking. All I did was fall in love unexpectedly. See – I married Richard, someone I wasn’t technically supposed to because he wasn’t from my background and didn’t share my cultural or religious heritage. After so many years it is easy for me to belittle this now, forget what it felt like at the time. It is easy to think of it as not even that big a deal anyway, as though telling my family about him wasn’t the most difficult thing I’d ever done. Lots of people have done what I did; I was certainly not the first. I tell myself that how I met Richard is unextraordinary and normal and therefore an unimportant story to tell. But later, I catch myself thinking of us and of our marriage and our children and of the life we are making together. I look around me and I allow myself to think of what it took to reach this moment and that’s when I realise: it does matter. I ask myself: what if my story, our story, might count? What if it might mean something?

Though there is plenty of the everyday in our story, because we are ordinary and watch Netflix and eat dinner on the sofa, it does not make it any less of a great love. Though the way in which we met was normal for the time, it doesn’t mean the stakes didn’t feel impossible or too high to scale when we were in the midst of trying to figure out what it all meant. It doesn’t mean it didn’t feel extraordinary, because it did. Perhaps no one would know to look at us what it took for us to be together. Perhaps parenting has left us too tired for it to show. We have been married for nearly ten years now. I notice the soft crinkles around his blue-grey eyes, count the silver strands that appear as if by magic in my dark hair, and it strikes me that we are growing older together. This astonishes me. I realise how in the ordinariness of the everyday the steadfastness of love is revealed.

I think about what Saima says. I remember how, when I didn’t know what to say to my family, I looked everywhere for a version of my story, something that might have helped me find the words I needed. I think of all the little questions my children have, and all the bigger questions that are yet to come. I wonder if they will understand that the story of how their father and I met is not so much about the specifics of when and where as it is about me, learning how to find the words I needed, figuring out what I felt, saying what I had to say even when I felt my voice falter.

For the longest time, our story has gone like this: we met in Tinderbox, a high-street coffee shop in Angel, long since closed, I believe. The story goes that he was stood in front of me in the line and I took his green tea by accident. He asked for it back and I said something like ‘Oh god, I’m sorry, that’s embarrassing’, and he said, ‘Not at all’, and that’s how we started talking. The rest, we say, is history.

Except it’s not. That’s not really how we met at all. I mean, it happened, we did go to Tinderbox and I did accidentally take his green tea instead of my breakfast one, and that really is what we said to each other, but it’s not quite the meet-cute it has been made out to be. It’s easy to get carried away, to start believing that we met by chance as if somehow that makes it more romantic. When friends, people our own age, ask us how we met (and it is surprising how many couples ask this of each other), they say things like how lovely it is, how rare for something like that to happen in such a vast place as London, like the Piccadilly People I guess.

I like this version of our story even though it is not strictly true. I like it because it implies a twist of fate. I like it because telling our story in this way also makes it less my fault. It means meeting Richard happened to me by accident, not that I made it happen by choice.

When our engagement was announced, my mother told some of our family and family friends that I met Richard in Regent’s Park mosque as if we both just happened to spend all our free time there. She said this, I think, in order to stress that his conversion to Islam was authentic and, perhaps more importantly, to stress that my behaviour was beyond reproach, to dampen gossip in the fairly conservative, relatively strict social circle that raised me and to put a stop to the question of what other people might think and say. If I met my husband-to-be in the mosque, it meant that I was a good sort of Muslim woman, and therefore my character came out of all of this intact.

Honestly though? The truth, the very unspectacular truth, is we met online. Of course we did. How else?

EARLY MARCH, 2011

I meet Richard for the first time on a Tuesday after work. It’s the beginning of spring in London. A cold chill runs through the sky, still bright and blue in the unwind of an early evening. We agree to meet outside Angel Tube station. I arrive early because I’m nervous.

I keep checking the time. Before leaving my flat, I consider what I might wear a thousand times. I’m more nervous about meeting Richard than I have been about meeting any of the strangers I’ve been set up with in the past through my mother, the Muslim internet, a South Asian matrimonial agency once featured in Metro, and the women I call aunties even though they are not related to me. One of these aunties sends me a sheaf of printouts of Arabic prayers in the post with a note that says if I read them seven times a day for three months, I will be bound to find someone. I wonder why she took the trouble to post the printouts to me instead of just emailing them.

Some of these aunties haven’t even met me, yet they have such faith in their powers of matchmaking that they reassure my mother that they can find someone, anyone, suitable even for a girl like me. I am almost thirty, only five foot two inches tall, I’m not a doctor and I can’t speak Urdu, at least not very well. My pickings are slim. I am not in high demand.

Most of the boys I am set up with are always in such a rush, always planning their next move. They send texts full of complicated abbreviations on the go and then want to meet the next day, no time to talk on the phone let alone send an email, their eyes darting fast and sharp around whichever restaurant or cafe we happen to be in, telling me before I’ve finished my tea that I’m not a long-term prospect, then moving on to the next girl.

But Richard and I have been writing to each other every single day for almost a month now, though we have not yet spoken on the phone. We write long, detailed emails with no emojis or abbreviations, emails which he composes perfectly, with paragraph breaks and an excellent command of grammar. I come to think of these emails as letters. As a writer, I appreciate the time and effort he makes to sit down and write, share the details of his day with me. There is something lovely about this. I find myself refreshing my inbox, waiting for his next email. We only swap phone numbers the day before we are due to meet. But I already feel as though I know him. I like everything about him. When I write to him, I feel as though I can tell him anything about myself. I also know that this sounds weird. It is 2011 and though internet dating is not unusual and there are already eHarmony adverts on TV, it is still something that people don’t like to admit to for fear of looking desperate. There is still the perception that internet dating is risky because you might end up with a psycho or someone a lot shorter than their profile states.

Most of all, I am nervous because even though I have been set up more times than I’d care to remember in the last five to seven years, I’ve never met someone who isn’t Asian. Someone who doesn’t share my family heritage, my skin colour, my cultural background or my faith. All of those so-called dates were legitimate because they were halal; I was only meeting boys who understood that these meetings were fast-track interviews to marriage and that there’d be no messing around. I am nervous because I know I can’t let myself like Richard. Richard is definitely not what my mother would consider a suitable boy. Technically I shouldn’t be meeting up with him at all. I remind myself that he started it. It is not as though I deliberately went out of my way to find someone who wasn’t from my background. I had tried the Muslim-specific matrimonial and ‘halal dating’ websites but let’s just say I didn’t have much luck. Any luck, in fact. So I thought I might have a better chance of finding someone who was still Muslim but also just a little bit more like me on a more regular sort of website. Or, as my brother’s friend Mo once said, a ‘middle of the road’ sort of Muslim. I tell myself the onus is on him. He was the one who messaged me, and my profile clearly said I’m Muslim. Surely he must know what he’s letting himself in for.

My best friend KK texts me. KK and I met at university. She went to convent school and her Nigerian parents are as strict as my Pakistani ones, which means her experience of the opposite sex is as limited as mine.

KK: Good luck!!!

Me: (something along the lines of) Don’t need it. This won’t be going anywhere!

Me: I mean, his name is RICHARD. What the hell am I doing with someone named RICHARD?

Me: WHAT WILL MY MOTHER THINK?

KK: Nothing. You haven’t even met him yet.

Me: WHAT AM I DOING?

KK: Just enjoy it! Go! Go!

The name Richard is a normal, perfectly nice English name but it is the very normality, the very Englishness, of it that bothers me. What’s in a name? Everything, I tell myself. Though I hang on to every email, each time I see his name in my inbox a tiny alarm sounds in my head, faintly but loud enough for me to hear, for it is in his name that all the small differences between us lie. I should be meeting someone called Rehan or Rahim or Raiyan, not Richard.

As it happens, my name is causing him some concern. Earlier that afternoon, he texts me.

Richard: I’m so sorry, and I know this sounds really stupid, but I realise I don’t know how to say your name.

Me: Oh! Yeah, I get that a lot. Don’t worry about it.

Richard: I don’t want to say your name wrong though.

Me: I do hate it when people get my name wrong.

Richard: Exactly why I don’t want to get it wrong.

I arrive early so that I might catch a glimpse of him before he sees me. I decide that I’ll see him first, and then if I really can’t go through with it, I’ll slip back into the station, text him that I can’t make it and go home again. I tell KK of my plan.

KK: You can’t do that.

Me: Why? He’ll never know!

I stand to the side and watch people pour out of the station in clusters. And then, there he is. I recognise him from his profile picture, which I may have looked at a number of times. I feel a little dizzy all of a sudden. He looks around for me and there is a frown on his face, a concern that perhaps he can’t find me. He reaches in his pocket for his phone. My phone pings.

Richard: I’m here! I’ll wait for you.

And he did.

THOSE DAYS

The idea that I would be married someday was something I understood and assumed ever since I was a girl. I had been to enough Pakistani and Indian weddings all over England and beyond to know that someday I too would be a bride, perched upon a stage with a face full of make-up in a tremendous sparkling outfit as heavy as a house, poised under bright lights, a camera zooming in on me. I don’t remember it ever being explained as such but I knew the system implicitly; I just did, in the same way I understood the rules about not talking to boys or dressing in a certain way. That one day a family might come to visit and then ask my parents for my hand in marriage for their son over cups of tea and a tray of samosas was as much a fact of my life as eating breakfast, reading books, watching Neighbours after school.

The summer my parents first spoke to me seriously about marriage was the summer between my penultimate and final years at Warwick university. We were on holiday in Italy and had caught the train from Venice to stay in Florence for a few days. When we arrived, we stopped at a large, busy gelateria full of ornate mirrors and hundreds of flavours where the servers happened to all be young and handsome, eighteen or nineteen years old, working summer jobs. Out of the blue, my mother exclaimed in Urdu how cute the blond boy serving us was and asked if I agreed. I almost spat my gelato out in shock. We never, ever talked about things like this, which is to say we never, ever talked about boys. I don’t know why I remember this detail, only that it seemed significant and odd given that the next time we sat down in another cafe, just a few hours later, my parents wanted to talk to me quite seriously about getting married.

I think the conversation began with me mentioning that I was interested in studying more after my degree. I had already spent a year abroad in Bordeaux in my third year and I was tempted by the idea of returning to France for a master’s after my fourth year, this time swept up by the romance of living in Paris. But then my parents interrupted and pointed out that since I was going to be graduating in the next year, perhaps it was time to start thinking about meeting some suitable boys instead of planning to go away again. There had been some interest, they said.

‘But I don’t want that. I don’t want to be looked at like that,’ I said. I felt my cheeks burn. I was annoyed and I wasn’t afraid to show it; my mood darkened and I pushed away my plate stubbornly like a child.

‘But this is how it is, in our culture,’ they said, before insisting that they were only asking me to think about it, nothing more just yet. To be fair, they really were only asking me to think about it, but at that moment I felt cornered. I was trying to tell them about my ideas and my plans for what I might do next, but they weren’t listening. As a teenager, I bristled whenever my parents reminded me of ‘our culture’, or told me that I couldn’t do something because it wasn’t ‘in our culture’, because it mostly felt like what they really meant was whatever it was we were talking about wasn’t up for negotiation. ‘Our culture’ was parental shorthand for ‘Don’t even think about it’ or ‘We’re not like other people.’ I had early-twenty-something dreams of living abroad, of maybe even becoming a journalist one day, of writing for a living, though I had no blueprint for any of this. And though marriage wasn’t part of my immediate plans, that is not to say I didn’t have hopes of one day falling in love, no matter how impossible the notion seemed. I didn’t know practically how this would ever happen, but that wasn’t the point. The point was I had dreams, no matter how clichéd they seemed. But ‘our culture’ brought me back down to earth.

It felt to me, in that moment, that what my parents were asking of me was stripped of any sort of romance – and I longed for romance. It is no exaggeration to say that I spent most of my teenage life reading nineteenth-century romance novels and they’d filled my head with all sorts of notions: meaningful glances, windswept proposals. In my barely turned twenties, when all summer long KK and I emailed each other about crushes and cute boys we had noticed on the bus or on the street (the extent of our experience) who may or may not have looked like Pacey Witter from Dawson’s Creek or Seth from The OC, I felt that even thinking about being introduced to someone in my parents’ front room was akin to being asked to give up on the smallest of possibilities. I had absolutely no interest in marrying someone who proposed via his parents in my parents’ front room.

‘Are you serious? Because I’m really not ready for any of this,’ I said. All my life, I understood I was to stay away from boys and not to talk to them but now it seemed I was being asked to sort of do the opposite.

‘You’re not a little girl any more,’ they said, not unkindly. ‘At some point you will have to settle down.’

I spent the rest of that day following my parents sullenly around the Uffizi, dragging my heels, wishing I was anywhere else but there with them. I was reminded about something I had read in The Portrait of a Lady, when Isabel found herself stuck with Ralph, having to defend her reasons for daring to turn down Lord Warburton’s proposal of marriage. I looked the parts up as soon as I got home and underlined them furiously: ‘I don’t see what harm there is in my wishing not to tie myself. I don’t want to begin life by marrying. There are other things a woman can do.’ And then also: ‘The other day when I asked her if she wished to marry she said: “Not till I’ve seen Europe!” I too don’t wish to marry till I’ve seen Europe.’ I decided to try the same tactic.

I had this idea of Paris in my head. I’d been to Paris before and there was a part of me that was swept up in what I thought was its loveliness. In my mind, Paris played out like scenes from Everyone Says I Love You and Amélie, a midnight sky lit up by swaying, unsteady fairy lights. I had this image of myself, living high in some pretty little attic room up in the clouds. I pictured myself surrounded by books, maybe even writing one. I imagined walking along the Seine at sunset, entire weekends lost in museums, watching French films in arty cinemas, perhaps even practising my French with some dreamy boy in a bookshop. It sounds like a string of clichés now but back then, to me, Paris meant simply that the world was full of possibility that I hadn’t explored yet. I wanted to reach out and hold it all in the palm of my hand. I wanted to run away, only with my parents’ consent.

At university there was an unspoken rule that I was to call my parents every night and go home on alternate weekends, and though I loved my parents very much, I also wanted to know who I was, who I could be, when I was fully apart from them. ‘It’s not you we don’t trust,’ they said. ‘It’s other people.’ I craved a certain distance but I couldn’t admit to this because I knew it would hurt them. All I wanted was to know that I could be someone, an adult, no matter how unprepared or terrified I was.