Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

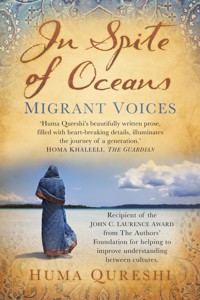

In Spite of Oceans: Migrant Voices explores the individual journeys of generations in transition from the South Asian subcontinent to England. Poignantly written, and based on real events and interviews, what emerges is the story of lives between cultures, of families reconciling customs and traditions away from their ancestral roots, and of the tensions this necessarily creates. We hear from the young bride from Bangladesh, married to a stranger, who comes to England to navigate life with a man she cannot love; from an Indian father who struggles to come to terms with his son's mental illness and hides it from people he knows; about how a mother and daughter's relationship was shattered in the clash over the Pakistani traditions her daughter chooses not to follow. Each narrative describes a journey that is both literal and deeply emotional, exploring the hold an inherited culture can have on the decisions and choices we make. At times heart-breaking, at times inspirational, In Spite of Oceans brings to life the pull of the past and the push of the future, and the evolving nature of what we understand as home.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 325

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Suffian

In spite of the ocean that now separated her from her parents, she felt closer to them, but she also felt free, for the first time in her life, of her family’s weight.

(© Jhumpa Lahiri, Only Goodness,

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2009)

Acknowledgements

My deepest gratitude to my publisher, Ronan Colgan, who read my writing and took a chance on me. Thank you, and everyone involved with the publication of this book at The History Press, for your patience and your confidence.

This book would never have been written were it not for the incredible individuals whose fascinating experiences inspired these stories. You shared with me your deepest emotions. I cannot thank you enough.

My heartfelt thanks to all those who helped with feedback on the early stages of this book. I am especially indebted to The Authors’ Foundation for selecting In Spite of Oceans for the John C. Laurence Award.

My talented best friend and fellow writer agreed to be my first reader. Thank you, Karen Onojaife. You are especially golden to me.

I could not have written this book without the support of every single member of my Qureshi and Birch family. You gave me the time and space I needed to write. All of you have been wonderfully patient with me.

I particularly thank my parents. My father’s memory lies somewhere in these pages. Amee, you remain an inspiration. Thank you for your unwavering belief in my many risk-taking leaps.

And also my brothers, Usman and Imran. Neither of you seem to think anything I write is bad and you both blow my trumpet for me at every opportunity in a way only big brothers can. I am one exceptionally and eternally grateful little sister. Saba, my sister-in-law, your infectious exuberance never fails to lift me. Thank you.

To my parents-in-law, I am humbled by your pride in me and I hope this book lives up to expectations.

And finally to Richard, who took care of our beautiful baby boy while I struggled with deadlines, self-doubt and writer’s block. You held the three of us together when I needed it most, at the times when I thought I would never be able to finish this book. You steady me each time I falter and have taught me to be kinder to myself, in spite of it all. For that, I thank you, always.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Quote

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

Learning to drive

2.

In the cracks

3.

The curfew

4.

Within four walls

5.

Teen

6.

English portions

7.

Potluck

8.

Crushed

9.

At the opposite end

10.

In spite of oceans

About the author

Copyright

Introduction

There is a framed black-and-white photograph that sits on the window sill of my childhood bedroom. It is of a woman I never knew. And yet there it is, in a place that I still call mine.

She has unlined almond eyes, thick heavy eyebrows and jet black hair parted deeply, held tight in a stiff, shiny wave fixed to the side as, I suppose, was the style. Her sari is pinned to her shoulder and she wears rings on every finger of her clasped hands, a few thin bangles clustered at her wrist. She is my mother’s mother, my naani, my grandmother.

She is not a smiling grandma; rather, her expression is halfway between sad and serious as she stares into the camera, her lips pressed together. She gives nothing away.

All I have of my grandmother is this, this old photograph in my bedroom in the house where I grew up in the West Midlands. There are no family jewels that have been passed along, no heirlooms that have stood the test of time. Even if there had been, it is not likely they would have travelled this far. Not across countries, continents and oceans, not all the way to England and not to me.

My grandmother died a long time ago. She died in Pakistan, far away from where she was born in Uganda. My mother, the second-youngest child of seven, was 14 years old when my naani passed away.

I don’t know much about my grandmother. Growing up, I never thought to ask. But now that I am older, now that I think about these things more, I wonder. I wonder about heritage and history and how this woman that stares at me like a stranger so blankly and, if I am altogether honest, sadly from behind a frame is in some way a part of me, if she is at all. Tell me, I think, looking at her photo. Tell me who you were.

More recently, I have asked my mother about my naani, from time to time. But what she remembers of that short period in her life when she, too, had a mother is blurry now.

This is what happens when your roots are rambling, overgrown from one country to the other in a tangled, wild nest that is home to more relatives than you ever really know. Time passes, memories mix facts with fiction and people forget how they got to where they are. My family history is not ordered, neat and tidy, logically flowing from one generation to the next. I cannot point at this name or that on an inked family tree and say ‘Yes, he owned this land,’ or ‘He fought that war,’ or ‘She came from this place,’ that I might then pick out on a map.

No, our story is not like that. My family history is the history of a family of immigrants. Many of my relatives, living or long gone, made their homes in different places starting first in pre-partition India and then in post-partition Pakistan, leaving a young country of unspoken promise to head further afield. One set of great-grandparents left to live in East Africa and work proudly for the British Empire. From there, one grandfather went to Saudi Arabia while the other engineered railways in the British Raj. Countless uncles and aunts forayed, one by one, out of Pakistan, followed by my own parents too, landing in England, where they stopped still; then cousins spiralling, now quickly and urgently, as fast as they can, to the Middle East, Australia and America. My big, extended family has spun like a spider’s silk web everywhere for decades, delicate skeins of DNA held together across lands first in blunt, capitalised telegrams and papery aerogrammes, now in virtual messages that take merely seconds to send.

All of these people I am related to left the places they were born, the familiarity of language, of food and of the faces they loved, for something else. Some left in pursuit of what they thought would be better lives; others left for what they felt was duty. Many left to fulfil ambition which they would not in all their pragmatism dare call dreams.

Sometimes they struggled, sometimes it was too hard. Some returned to Pakistan permanently, to their homeland and their mother tongue, building new houses with foreign money and saying sadly with a smile, ‘Well, we tried.’ Sometimes they fell in love with their new surroundings. Some of them, like my parents, stayed in one place, raising children who spoke differently to them and whose references of childhood were so far removed from what they once knew. It was us, the children, who rooted them steadfast in humdrum suburban towns that became home. And so, as years passed, places like Pakistan for my father or Uganda for my mother faded further and further away.

I may not have made the journey my parents made, but it is because of them that I am here, an adopted Londoner now. The choices they made long before I was born determined who I was to be and the path I would take. My past, surely, explains my present.

This is the connection I have explored in all of the stories that follow. The stories are inspired by people I have met. Some of them left south Asia behind and have long since made Britain their home. Others are like me, born and raised in one place but with a heritage from afar.

The people behind these stories have shared fragments of their quiet histories with me and I have, at times, filled in the gaps between the pieces they provided using my imagination. At these times, I have envisaged scenes and asked myself to wonder how some moments may have been. All the while, the essence of these individual experiences has been preserved.

Every story is, in its own way, a story of a journey. Sometimes the journey is literal, moving across oceans. Other times it is intangible, a journey of understanding and, often, coming to terms with what some call circumstance and others call fate. Each of these stories explores, in its own way, the connection to a different land and a different time, place and culture somewhere on the Indian subcontinent. Sometimes that connection is cherished and celebrated. Other times it is severed abruptly with hurt and pain. In some cases, it is simply something that just cannot be shaken or thrown away, binding us against our will, or forever in the background, quietly humming. Sometimes the connection is strong and loud, other times it is vague, weak and fading. But no matter how subtle it is, it is always there, a reminder of the past forever present and the journeys we make to be who we are, where we are, today.

1

Learning to drive

Afra travels light. In her small suitcase, she carries only one simple sari, three long dresses, a cardigan and a few plain undergarments. In the inside pocket of her handbag, she keeps her passport and copies of her maths degree.

It is not much, for a young woman about to move countries. It is even less, for a bride. She does not mind. She does not care for her dowry, the heavy saris her mother gave her or the gold gifted to her by her in-laws.

‘I will not need them,’ she tells her mother and her mother-in-law when they try to give her ornate saris to carry, telling her a wife will need more than what she has packed. ‘I will not need them where I am going.’

There is not much of her dowry left to take, in any case. Weeks after their wedding, she gave most of her trousseau away after Abbas told her she looked like a prostitute in the saris her mother had picked out for her in her favourite colour, the oranges of henna stains, and painstakingly folded into the wardrobe her father had bought for her to take to her new marital home. Her in-laws, new cousins and cousins’ wives and aunts and women whose names she was yet to learn, bounded into her room, plucking free saris in varying shades of amber and ochre and autumn as if the rice harvest had come early to Sylhet this year.

‘Take them,’ Afra shrugged. ‘Take them all.’ As they helped themselves, they thought her a funny girl, to give her beautiful clothes away.

Later, Abbas threw the few things that were left into the courtyard in a drunken rage. Her clothes, the plain ones she had stitched herself; dinky pots of lurid make-up pastes given to her by her college friends; inexpensive but pretty little bracelets from her four younger sisters; her father’s copy of Agatha Christie’s The Murder at the Vicarage which he said she could keep; folders of maths notes from the degree she was studying for before the marriage proposal came. Abbas threw it all into the courtyard, storming like a hurricane towards her.

‘I never wanted this! I never wanted you!’ He jabbed his fingers towards her, pushed his face so close to hers she could smell his sour breath and see the spittle bubble on his cracked lips. The few things she had kept for herself lay ruined in a dirty heap in the middle of the courtyard. Afraid of her new husband to whom she had been married for less than a month, she turned and ran while her mother-in-law tried desperately to restrain her son. ‘I never wanted her!’ he screamed at his mother. ‘I never wanted her! You did this!’

That was nearly a year ago. Afra has not seen Abbas since. After he threw her things into the courtyard, his brother hurriedly arranged for Abbas to go back to England, where he had been living before his wedding to Afra and where it had already been decided upon their brief engagement that she would join him.

‘You go back and you make things better,’ he told his younger brother. ‘You make a living and you go back with her.’

Abbas left quickly but Afra did not go with him. In the first interview for her visa which her brother-in-law had arranged for her at the British High Commission in Dhaka, Afra told the commission officer in the privacy of the interview room that she did not need a visa after all.

‘I am married to a stranger. I do not want to go to England with him. I want to stay in Bangladesh,’ she said in her college-taught English, shunning the interpreter who looked on, stunned by this young woman who was not even trying to impress like all the others who came in nervous and polite, overdressed in smart shoes and starched clothes and desperate for the stamp on their passport that would let them leave for a new life.

The officer raised an eyebrow, nodded and said ‘Very well’. Then he refused her application and wished her the best.

But now Afra is going. In her second visa interview she told the officer, a fair-haired Englishman named Mark, that she was ready to leave.

‘I have heard a lot about England,’ she said. ‘I have heard I can get an education there. Here, I just do everything for everyone else. In England, perhaps I can stand up on my own two feet. I will work there. I will get a job. It is the only place where I can be free.’

The officer looked at her, this small, serious woman who, according to her passport, was only 19 years old.

He deliberated and then he said, ‘No more questions.’ Her passport was stamped immediately, and her small suitcase has been packed ever since.

Abbas is on his way back to Bangladesh from England for the first time since their marriage. He is coming to collect her. After six weeks, they will leave together. Her mother and her mother-in-law are proudly telling everyone, relieved at finally being able to say, ‘He is coming for her, she will go with him. They will be happy in their lives together.’

Though Afra has had her suitcase packed, she is not excited like her mother. But she is ready to go. She is frustrated and bored, being a wife in Bangladesh to a man overseas, when all she really wants is a job, a purpose, something to call her own. Still, she does not know what they will do for money although she read in a letter to his mother that Abbas has a job as a waiter now at a friend’s restaurant in a city called Durham. She does not know much about Durham. But the thought of moving to an unknown country and an unknown city does not scare her. She just wants to go.

Her father gives her a notebook. It is filled with neatly written phone numbers of uncles and aunts, who are not relatives but friends of her family settled in London. He tells her these friends will look after her no matter what she needs. This notebook and the copies she carries of her maths degree calm the few sparkling nerves she allows herself to feel. She is weary of Bangladesh and she wants to be free.

Afra was not told married life would be like this. She was told her husband was a straightforward man, an honest man, that is what her family said. She thought, at the very least, that he would speak to her kindly and that one day, perhaps, they might love each other. But it has not happened yet. For how could it? He has been away for so long.

Though her throat tightens when she thinks of parting from her father, she hopes the distance this new country will bring will separate her from the hurt that those around her brought to her, put upon her and bound her in. She hopes her hurt will scatter and then disappear, like the tear-shaped raindrops that fell so heavily the month she married.

When she was young, she had been promised much. First it was little things, a bike and new books. And then it was bigger things, an education and a job. Her father wanted it all for her, his eldest daughter whose name he called out first as soon as he got home. In his gestures and words, he promised her the world. He promised her a co-education at the college he went to, a modern life ahead of her of independence.

It was the late 1960s. It was East Pakistan. Afra’s father was a liberal and he believed his little girl could grow up to be different to the women that had surrounded him all his life. He had seen first his sister, and then his own wife, limited by their basic primary school education, prepared only for marriage, housekeeping and nothing else. Afra would be different, he decided. He took her to the library, cycled with her on the back of his bike, talked to her about books, and other things she did not yet understand like politics and college courses even though she was still a child.

‘One day,’ he said proudly as she showed him her latest round-up of top marks from school, ‘one day this daughter of mine will be so successful! She will drive a car, and I will sit at the back and she will take me around. Just watch!’ Her mother shrieked in shame. No daughter of hers would ever drive a car, she retaliated.

But the dreams both Afra and her father had hoped for never came or if they did, they were quickly taken away. For a day she rode on a shiny new bike from her father before her mother replaced it with a sewing machine, declaring it a far better way for a teenage girl to pass her time. When her father brought home bundles of new books he thought would expand his daughter’s young mind, her brother wrote his name in them instead.

Then in 1971 things changed. Her father, a customs officer for the government, grew terrified of the soldiers from West Pakistan who ruled violently in the streets. Twice they came for him. Twice he begged to be freed and then refused to speak of what had happened to him, shaking his head gravely instead, turning blankly away, unable to look into another person’s eyes for too long. Brave men, liberal men like her father, lived in fear of a bloody civil war that threatened their everything.

Her mother made Afra stay home and indoors, away from the stories they heard of the rape of young girls, of torture, of beatings and kidnappings. Afra was only 10 years old when the war broke out but her mother, who was married herself at 11, insisted she be married quickly because five daughters in the house was a risk.

‘Let her be protected in her husband’s house. We cannot let her go out,’ she urged in a whisper.

Her father grew quieter, his face worn and worried and resigned. He agreed.

‘It is for the best, beti jaan,’ he told Afra when he explained she could not return to school for a year.

Afra’s mother looked every day for the red smudge of blood that would declare her daughter’s readiness for marriage. But for two years it did not come, despite her prayers. When it finally did, the war was over and then all of a sudden, the rush of suitors did not stop. Their mothers and their sisters came to drink tea at their home and eat the snacks Afra had prepared. Some were families they already knew from Sylhet, others travelled from afar in serious search of a bride. Sometimes the prospective grooms came too. They were older than Afra and casually looked up from their china cups from time to time, watching her with an indifference which implied they were not there for her at all.

Afra did not have to resist being married all these years; her father did it for her. He enrolled her in the college he himself had attended, as he always said he would, and she was fast becoming a top maths student. Her tutor suggested finance as a career and her father approved. But he always left the house when the suitors and their families arrived, and later he argued about it with her mother.

Afra’s younger sisters, who did not understand the seriousness of their parents’ fights, poked her. ‘You are always his favourite!’ they cried. On days the arguments were particularly bad, their mother made their least favourite food for dinner, sloppy dhaal and aloo bhaji which she served unsmiling and they ate in silence.

But her father knew he had put off Afra’s marriage for as long as he could. His mother, his sister-in-laws, everyone kept asking why he had not yet found a groom for Afra. One afternoon, when Afra was 18 and unwed for eight years longer than her mother would have preferred, her father met a man in a restaurant, a friend of a friend. His name was Abbas. He had come from England and was looking for a Bangladeshi bride.

‘And what do you do there?’ her father asked, prepared for the usual exaggerations the Bangladeshi men from England made about their fabricated empires of restaurants and business chains. But this man was honest.

‘Right now, I do not have a job. But I am planning to find one as soon as I am settled with the woman who shall be my wife,’ he replied.

‘He is not like others,’ Afra’s father thought. ‘He is not pretending to be someone he is not.’ That night, he invited Abbas, his mother and his sister to meet his wife and daughter in their home.

Even though she did not feel attracted to this bald man with a moustache who was twelve years older than her, Afra could not say no to her father. Besides, she trusted his choice more than she would ever trust her mother’s. Her father was her friend.

‘You will go to the Queen’s country,’ he laughed. ‘You might even drive a car,’ he joked, making light despite knowing he would miss her terribly.

‘But what about my studies?’ she asked.

‘He is an educated man,’ said her father. ‘He will agree to let you continue, of that I’m sure.’

Within a month, Abbas and Afra were married.

But even before his show of rage in the courtyard, Afra realised Abbas was not the straightforward, honest man her father believed him to be. She had seen him, the night of their wedding, sipping from a green glass bottle, his eyes unblinking. Abbas barely spoke to Afra. When eventually he touched her, Afra lay motionless, her eyes shut fast and tight. Her mother had told her that this was a thing that men do, but nobody had told her it would hurt so much.

For months, neighbours have been asking, ‘Why is Afra still here? Why has Abbas not come for her?’

They have enjoyed answering their own questions with their own wild speculations. Afra ignored most of them, but she is tired of their blunt curiosity peering into her life to take of it what they can and spread around. Once, she sarcastically replied that her husband had taken a second wife, an English lady with pale legs wrapped in short skirts.

‘What am I supposed to say?’ she said stormily to her mother who scolded her like a child when the gossip made its way back to her. ‘That my husband doesn’t like me? That my husband doesn’t want me?’

Now, though, her mother is pleased. She can tell the neighbours that her eldest daughter is leaving for England, and that once there, her wifely duties will start. She is slightly sad to see Afra go, slightly afraid of what her daughter might do when she gets there, but she has four daughters yet to marry, headache enough, and she prays the status of an eldest daughter settled overseas may bring with it better prospects for the younger ones. And so it is better that Afra goes, her mother thinks.

‘And at least the girl is still married,’ she tells herself, muttering Astaghfirullah, a quick utterance to Allah for redemption, when she thinks of what could have been.

After Abbas threw her things into the courtyard, Afra, who does not normally cry, wept alone for what felt like hours, heaving silently atop the double bed made especially for the newlyweds. She cried because her husband, the man her father chose for her, called her a prostitute when she had never let herself be touched before and it hurt her badly to hear the slur. She cried from anger and because she felt deceived. Mostly, she cried because she did not know what or how the rest of her life with this man would be. She had heard the gossip start, taunting and tactless, just after her wedding day; that Abbas was a drunk and that Abbas was depressed. She had heard from the servant girl that Abbas had threatened to marry an English girl, which prompted his mother to collapse and his brother to order him back to Bangladesh where he had set up a meeting with the father of an eligible bride in a restaurant.

‘So that’s why,’ she realised. ‘That’s why he hates me.’

But as the call for evening prayers came, she splashed her face and clenched her jaw and vowed not to let her in-laws see her cry. She prayed and then decided she would return to her parents’ house. She announced her decision to her in-laws steelily.

‘If I am not wanted here, I will not stay,’ she said.

Her in-laws gathered around her and promised Abbas would not always be like this. Her brother-in-law cycled quickly to fetch her parents to persuade her not to leave, for a bride simply could not walk out of her marital home so soon. But her father cried when he saw her.

‘My beti, what a mistake I made choosing this man,’ he said, clasping Afra’s hands and breaking her heart into a million tiny shards of splintered glass that would never quite fit perfectly back into place again. ‘Allah will never forgive me. I will take you back.’ But before Afra could collapse into his embrace, her sister-in-law and aunts-in-law hurried him away.

‘This is something for the women,’ they shooed. ‘Let us women sort it out.’

Her mother sat next to her on one side of her bed, her mother-in-law on the other. Each woman held one of Afra’s hands. Her mother spoke first.

‘I know you are determined. But you are the only one of my five daughters who is married. You are the eldest. If you leave this house, what will your sisters do? Think of them. Think of me. Think of the family’s shame.’

Afra tried to speak, tried to resist, tried to tell her mother that she would look after her sisters herself, make sure they got better than this. She tried to tell her that she would be no burden, that she would work as a bank clerk and earn her own keep. But she was numb and exhausted and her body ached. The words did not come.

‘If you leave this marriage, Afra,’ said her mother, continuing more firmly now, ‘I will have no choice but to leave this world myself. Promise me you will not leave.’

Bewildered, Afra turned her head slowly and, yet slower still, understood. She understood that her mother’s pledge left her bound in this marriage to a man her father had met just once in a restaurant before deciding he was right for her. She did not begrudge her father; he was not to have known.

‘All couples fight like this,’ her mother-in-law said. ‘Understanding comes later. I will take care of you myself. I promise you.’

And like that, her decision was made. Afra could not leave Abbas, even if he himself went away, not with her mother’s threat to take her life laid out before her. Much to her surprise, her mother-in-law kept her promise and looked after her well. As soon as Abbas was gone, private tutors were arranged so she could catch up on her studies and finish her degree. Though the rest of the family, Abbas’s sisters and aunts, complained it was not necessary, her mother-in-law stood firm. ‘I promised her this much,’ she said. Even though Afra could never quite shake the feeling that her mother-in-law was motivated into kindness more by the fear that her son might marry an English woman than by a promise to her daughter-in-law, between them a surprising friendship was formed.

But despite her mother-in-law’s company, Afra has felt alone this year. She agreed to write letters to Abbas, although they are dull and formulaic, telling him what they had to eat, what she did that day. She has not told him that sometimes, she feels stunted, dead inside. He does not reply to her directly, sending his replies addressed to his mother and brother instead. The understanding her mother-in-law spoke of has not come yet.

When Abbas arrives home, there is a commotion in the courtyard as his family clusters around him.

‘Where is Afra? Come, meet your husband!’ her mother-in-law shouts not unkindly, up towards Afra’s room. She goes downstairs. He nods salaam and Afra slightly bows her head.

‘So, this is our reunion,’ she thinks. ‘This is how he greets me. My husband.’ Later, in the middle of the night, Abbas comes to bed. He touches Afra again but they do not speak.

Afra has said goodbye to her sisters and her parents and her brother again and again over the last six weeks while Abbas has been back. She promises her sisters she will write to them and tell them all about England and the Royal Family. But it is not until they arrive at the airport that their goodbyes are final.

Afra has never left Bangladesh before and inside she feels something like electricity popping in her stomach in quick, sharp, short bursts. Her parents sob and this makes her feel heavy and sad.

‘You are in Allah’s hands now,’ says her father. ‘He will take care of you.’ Her mother wails and sniffs prayers loudly over her head while her mother-in-law dabs the corner of her damp eyes with a shawl. Abbas’s mother is used to airport goodbyes for she has seen Abbas off to England many times. Her cries are quieter, those of a parent accustomed to waving off an immigrant child. Afra’s brother is the last to embrace her.

‘England is a free country, I have heard,’ he says in her ear. ‘But if I hear anything about you, any scandal at all, any of this talk of leaving him again, then there will be news for you. Now go, and be good.’ Afra does not cry as she waves goodbye.

Afra has not been on a plane before and Abbas snorts at her when she inhales sharply as they take off and she tightens her fists over the armrests. When she vomits into a paper bag, he shakes his head. She spends the flight vomiting and sleeping and praying and, sometimes, fighting back tears. She thinks of her father and misses him but remembers his glee, his voice declaring, ‘You are going to the land of the Queen!’ She thinks of what he used to say when she was a child, about her driving a car one day. She wonders if in England, that might be true and a hint of a smile tickles her face.

The cold in England is frighteningly deep. It is winter and the snow, which Afra has only seen in pictures before, is far harsher than its beauty portrays. She is shaken by it. She realises, embarrassed, her mother and mother-in-law were right to press her to take more clothes. But then how was she to know? Abbas never spoke to her of what to expect. He never speaks to her at all.

They land in London, sleeping overnight in a damp spare room belonging to a distant acquaintance Abbas knows, before catching the train northwards the next day. All the while, Afra has not been able to stop being sick. When she vomits, Abbas glances, derision curling his lip, at his overseas bride who is not built for a climate like this.

‘I must not let him see me like this,’ Afra thinks. ‘I must not let him think I am weak.’

But it is hard for her. She cannot eat and she wonders if this is what it is like to be homesick even though she insists to herself she does not miss Sylhet one bit. Weeks later, their landlady, a kind Bangladeshi woman named Bilqis who lends Afra cardigans and charges Abbas rent at £30 a week, takes her to hospital. Bilqis, who has three young children whom Afra plays with, is right.

‘You are expecting your first child,’ the doctor says. ‘Congratulations.’

That day, Bilqis, Afra and the children celebrate with ice creams and Lucozade, two of the few things that soften Afra’s relentless morning sickness. Bilqis buys Afra a navy blue sari from an Indian fabric store for £10. ‘A gift for the mother-to-be,’ she says.

Abbas works at the Taj Mahal restaurant every night until midnight, and when eventually they are awake at the same time long enough to speak, Afra tells him.

‘I won’t look after this baby,’ he tells her, monotonously. ‘You will have to do it alone.’ He turns over, his back a bare wall before her, and goes to sleep.

Afra does not cry, nor does she argue. She may be bound to Abbas for life by her mother’s blackmail, but she resolves she will not owe him anything. Besides, she does not feel alone any more. ‘My baby,’ she writes in a letter to her sisters to tell them the news. ‘My baby is all mine! I am so happy. No one can take my baby away from me!’

The snow thaws into spring and the sourness of her morning sickness fades and, renewed with purpose, Afra begins to think of what to do here, in England. She borrows Bilqis’s sewing machine, turning fabric scraps into pretty little dresses because she is convinced her baby is a girl. Bilqis, impressed by Afra’s sewing, offers her 50p to alter this child’s trousers or the other child’s skirts.

‘Can you sew Bangladeshi clothes?’ she asks.

‘I can sew anything,’ Afra replies, confidently.

Slowly, young Bangladeshi and Pakistani brides from Durham and Newcastle, friends of Bilqis, come to Afra with sari blouses that need taking in or necklines and hemlines they want her to edge with rolls of colourful brocades for 50p. On Bilqis’s advice, she saves the money secretly from her husband, sewing while Abbas works both afternoons and nights. Sometimes she spends the money, buying fabric for herself, making simple clothes to add to her small wardrobe or yet more tiny dresses for her baby. In the mornings, she wakes early while Abbas still sleeps, walking to the library where she spends hours reading Agatha Christie, whispering English words to her soon to be English-born baby. She barely sees Abbas, who is at the restaurant or with his friends, all the time.

With Bilqis and her small circle of new friends, the chattering women she stitches clothes for and the ladies who work at the library, Afra feels lively like a college girl again.

They take trips to Newcastle to browse large department stores. Afra spends hours in the haberdashery floors, fingering the soft fabric of beautiful dresses for baby girls which, even with her sewing money, she can scarcely afford. She vows to buy at least one for her daughter, whom she has already named Amina. ‘She will be like me, but she will have more than me,’ she thinks, a hand absentmindedly resting on her stomach. ‘Whatever I can give to her, I shall.’

Afra plans for Amina’s future. One day, she asks Bilqis for directions to Durham University and finds the office in the maths department. Proudly, she thrusts them copies of her Bangladeshi college degree and asks what she needs to do to enrol. But she is disheartened when she leaves, embarrassed she did not realise her limitations. ‘We can’t accept an overseas student on a visa just like that,’ the clipped accented woman in the administrative office says. ‘Besides, you’re about to give birth anytime now.’

Amina is born during a hot, still night in the summer of 1981. Abbas takes her to the hospital but asks not to be woken when the baby comes. ‘I need my sleep, I have to work,’ he says.

Afra does not care because time stops still with Amina. She is all Afra can absorb, gazing at her for hours.

‘Amina,’ she whispers when the baby is handed to her in a moment so precious her heart feels full again. ‘Amina, my child.’

Abbas receives stern letters from his family in Bangladesh. People are gossiping, saying Abbas cannot look after his baby and his wife, mocking that the three of them live in a rented room alone. Once again, the family faces shame, his brother tells him. ‘You must behave as is expected of you,’ his brother writes. ‘Be a man.’

Abbas comes back to Bilqis’s house and tells her they are moving out. He has acquired a loan of £10,000 from an acquaintance and found a flat for them in Newcastle to buy. Afra never asks whom he has borrowed the money from. She does not want to know. She does not want to go, either, but Abbas never asked her how she feels. ‘I need you to pay me £50 a month for the loan,’ he tells her instead. ‘That is your share.’

Afra wonders what her father would say if he knew her husband demanded money of her. But what little she knows of Abbas from their short years of marriage, she is not surprised.

‘Such a beautiful girl, married to such a miserable man,’ Bilqis says sadly, shaking her head as Afra, holding Amina, leaves.

Newcastle is difficult for Afra. She misses Bilqis and her three children and her friends. She misses the library, where the ladies behind the counter always waved at her and never complained when she brought Amina in.