3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

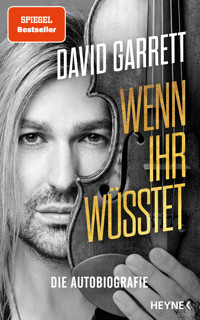

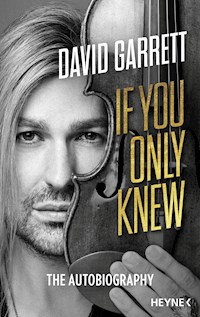

- Herausgeber: Heyne Verlag

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The only autobiography of „the greatest violinist of his generation“ (Yehudi Menuhin)

The road to the pinnacle of violin-playing has not been an easy one for David Garrett. His childhood revolved around discipline and working daily with his father, who fostered his talent and supported him, while also being an ambitious driving force. From the tender age of ten, he was already performing on stage with the world’s greatest orchestras, later playing all the classical works as a teenager, before freeing himself from the shackles of his wunderkind existence in his early twenties and moving to New York to study.

It was in that city that he laid the foundations for a new genre of classical music in the form of „crossover“, combining virtuoso violin music with the latest pop, which made him more famous than ever before. David is the perfect embodiment of a young man’s onerous quest to carve out his own path and live authentically, finding his very own solution to this problem by fully committing to something that could just as easily have destroyed him as a person – music.

In this autobiography, we witness his world through his own eyes; the dazzling highs, along with the sweat and tears – a dramatic, inspiring and touching book for all fans and music-lovers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 441

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

The only autobiography of „the greatest violinist of his generation“ (Yehudi Menuhin)

The road to the pinnacle of violin-playing has not been an easy one for David Garrett. His childhood revolved around discipline and working daily with his father, who fostered his talent and supported him, while also being an ambitious driving force. From the tender age of ten, he was already performing on stage with the world’s greatest orchestras, later playing all the classical works as a teenager, before freeing himself from the shackles of his wunderkind existence in his early twenties and moving to New York to study.

It was in that city that he laid the foundations for a new genre of classical music in the form of „crossover“, combining virtuoso violin music with the latest pop, which made him more famous than ever before. David is the perfect embodiment of a young man’s onerous quest to carve out his own path and live authentically, finding his very own solution to this problem by fully committing to something that could just as easily have destroyed him as a person – music.

In this autobiography, we witness his world through his own eyes; the dazzling highs, along with the sweat and tears – a dramatic, inspiring and touching book for all fans and music-lovers.

WILHELM HEYNE VERLAGMÜNCHEN

The contents of this ebook are protected by copyright and contain technical safeguards to protect against unauthorized use. Removal of these safeguards or any use of the copyrighted material through unauthorized processing, reproduction, distribution, or making it available to the public, particularly in electronic form, is prohibited and can result in penalties under criminal and civil law.

If this publication contains links to third party websites we assume no liability for the contents of such sites as we are not endorsing them but are only referring to their contents as of the date of first publication.

The publisher has made every effort to locate all holders of rights and to name and pay them as is customary for the publisher. If this has not been possible in every individual case due to the passage of time and a lack of availability of sources, we shall of course fulfil any justified claims.

David Garrett’s memories served as the basis for the dialogue and events contained in this book. The conversations are reproduced mutatis mutandis. No claim is made as to the verbatim reproduction of actual dialogues that have taken place.

To protect individuals who are not public figures or family members, some names have been changed.

1st edition 2022

Copyright © 2022 by Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich, Germany,

part of Penguin Random House Verlagsgruppe GmbH,

Neumarkter Strasse 28, D-81673 Munich, Germany

Editor: Evelyn Boos-Körner

Advisor: André Selleneit, plan B – konzepte: Jörg Kollenbroich,

Weigold & Böhm International Artists & Tours GmbH: Tobias Weigold-Wimmer

English edition: booklab GmbH, Munich, Germany

Translator: Emily Plank

Editor: Diana Vowles

Typesetting: BUCHFLINK Rüdiger Wagner, Nördlingen, Germany

Cover design: Hauptmann & Kompanie Werbeagentur, Zurich, Switzerland

Cover photo: Christoph Köstlin

Picture editors: Sabine Kestler, Heike Jüptner

e-book production: Satzwerk Huber, Germering

ISBN: 978-3-641-30699-1V001

www.heyne.de

When can we speak of success?

When we succeed in making others happy.

With this in mind, I dedicate my book

to all young musicians.

As long as you love music

and keep up your curiosity,

you won’t regret taking this path.

Content

Foreword

I should have said ‘no’

This impossible instrument

A childhood with violins

Exceptional circumstances

Bring on Tchaikovsky

David Bongartz becomes David Garrett

Ida Haendel

Luigi Tarisio and the Messiah Stradivarius

Mind over matter

Isaac Stern

Yehudi Menuhin

The piano is too loud!

Of love and heartache

The secret tape

Digging deep

Intermezzo in London

Snow flurries in Manhattan

David Garrett becomes Christian Bongartz

Dinner with Itzhak Perlman

The Juilliard experience

Five ways of earning money in New York

A foretaste of crossover

Getting the ball rolling

Daniel Kuhn and the black Amex

Flat-sharing with Alexander

An old hotel in London

Sixteen hours in economy class, middle seat

Support act for Jools Holland’s England tour

Breakthrough

La Grotta

Love over money

Johann Sebastian Bach to the rescue

New York, New York

On tour in Europe and the US

The loneliness of a violin soloist

My tour schedule, 2009 to 2019

Violin crash in London

Guarneri, Stradivari & co.

Why I don’t recommend stealing a Stradivarius

The Devil’s Violinist

‘What’s Mr Garrett like?’

Tour craziness

Every day is not a Sunday

Not too much serious classical stuff, please

Spring in Hilversum

Appendix

Link to additional material

Picture credits

List of works

Foreword

Before we get started, here’s a brief introduction to my book.

Throughout my entire life, I’ve always steered clear of the beaten track. Of course, there have been times when it wasn’t easy to forge an alternate path, but life is a journey of discovery, after all. It’s true: I never seem to get tired of gaining new, surprising perspectives, and I always make sure that I pay close attention to the tiniest of details that ultimately make up the complete picture.

This is the attitude – one full of curiosity – that I have adopted when tackling any project in my life, be it in music or business. For me, a project always starts with an initial great idea, a sort of epiphany, and it was one of these that inspired the word ‘phygital’, which describes the concept of my book. It’s basically a fusion of the physical and the digital, of the old and the new. I’ve always found it fascinating to combine them in new and exciting ways.

What it means in the case of this book is that all you need is a bit of curiosity, a smartphone for the QR codes, and you’re ready to go. The many previously unreleased pictures, videos and sound recordings will give you additional insights into my life, beyond mere words. For the first time ever, I am unlocking my private archive of audio files and images that my parents and I have collected over the decades – so you’ll be part of the journey as I recount my experiences, both the happy moments and the less enjoyable times. At the end of each chapter, you’ll find a QR code that will take you to additional, previously unpublished photos and videos. If you don’t have a smartphone handy, you’ll also find the weblink to the additional material in the appendix.

As you will see, even in this project, there’s no escaping a term I’m not at all fond of: ‘crossover’. But this term has now also become a classic in its own right, so ...

I really hope you’ll enjoy being part of my journey,

At the end of each chapter you’ll find a QR code which holds as yet unpublished photos and videos. If you don’t have a smartphone, you’ll find a link for the additional material in the appendix.

I should have said ‘no’

Photo from the Rock Symphonies album booklet, 2010

I should have said ‘no’ when Mascha ambushed me, asking me to go out with her that night. I knew, of course, that the long New York nights would end up even longer with her, and that wouldn’t have bothered me except that I also knew I was expected at the Electric Lady Studio in Greenwich Village at 9 a.m. the next morning. The preparations for RockSymphonies were complete. The following day, we wanted to start recording the pieces live; there would be a few corrections to be made, as usual, and it’s even possible that some planned tracks would be discarded at the last minute and new ideas tried out. So there was a lot at stake; crossover productions keep things exciting right until the end, but that’s exactly what I like about them, particularly as the crazy atmosphere at that studio always adds a whole extra level of fun to the work. The ghost of Jimi Hendrix, who had brought the Electric Lady Studio into being, probably still lurks around the garishly painted rooms – who knows. In any case, things were finally going to be kicking off the next day at 9 a.m. I should have said ‘no’. But I said ‘yes’.

Of course, it turned out to be a very, very long night. Mascha loved to party, and once again there had been no stopping her – she was the embodiment of joiedevivre. I have to say I really loved that exuberance – in fact, it was one of the reasons why I found her so irresistible. We eventually fell asleep at 6 a.m., and, only two short hours later, at 8 a.m., I reached over to my phone, obviously still quite wasted, and called my producer. For the first time in my life, I had to cancel a studio session. What’s more, that was the moment when I decided to break up with Mascha.

Was it her fault? It takes two to tango, I know. I was annoyed at myself more than I was at her, but I secretly would have loved, just this once, for Mascha to have reined in her unbridled zest for life – for her to have been the more sensible of the two of us, just this once. Except that wasn’t Mascha. It was not in her nature to talk sense into me when there was partying to be done. I came to the realization that this relationship wasn’t doing me any good. Things were heading in a direction I really didn’t like. Of course, I still found her magnetic energy and lust for life hard to resist, and it was just too nice, just too easy to lose my head with her and end up making the wrong decisions. Yes, it had been an amazing night, but I had lost control. Now, my guilty conscience was almost killing me, and this conscience was right: the new album was the #1 priority. Music was more important. It was my life. When it comes to work, a lack of discipline is one of the deadly sins. I should have said ‘no’.

Is that what you get for always being a wunderkind? No, I don’t think you can put it like that. I must have been twentyeight when I broke up with Mascha, and by then I had long started my second life – far away from Germany, in Manhattan, New York. In this new life, I could do and not do whatever I wanted. And I did just that, except that in the background there was still always that old friend that had dogged me since childhood, that voice I couldn’t shake off: my guilty conscience. We don’t particularly like each other, but we know each other very well. To this day, this conscience especially tends to rear its head in my dreams, and I’m once again that serious nine- or ten-year-old boy with his violin who was expected to achieve great things; who wanted the greatest violinists, the most famous conductors of the time, to recognize him as one of their peers; a boy who would therefore creep downstairs through the empty house at night, while everyone else was asleep, take out his violin and secretly keep practising, because, hours before, he had noticed the frown lines on his father’s forehead – an indication that the day’s goal obviously had not yet been achieved, and that perfection was still out of reach.

Settling for anything less than perfection was out of the question. It was the only acceptable goal. I had huge expectations to meet, and I certainly wanted to meet them. I just wanted to please everyone. But what happens when you can never ever please your parents or teachers? When, 24/7, 365 days of the year, you’re required to perform well, to make progress, to be somewhat better than yesterday and definitely a lot better than the day before that – in other words, meet expectations that can never be met, because these expectations grow along with your abilities, and because the bar keeps being raised a few centimetres higher, with no end in sight? What happens when, despite all the progress you’ve made, you go to bed every night feeling that, once again, you are not enough? That’s when the bad dreams come, and, with them, the fear of failure, of not passing the test, of being unprepared, and therefore disappointing everyone. Leaving Mascha was a panic reaction.

Was I still in love with her? Yes, absolutely. Did I want to continue the relationship with her? Absolutely not. What Mascha may not have known is that she had supremely powerful rivals. Prominent rivals, namely world-famous violinists and conductors, who would scrutinize me intently the first time they laid eyes on me as a young person with my violin. They all wanted to know: how serious is this lad about music? Is he aware of the scale of his task? Does he realize the amount of work and responsibility involved? Or does he come across as childishly flippant? If so, then he’s out. He’ll have no future, he won’t make it, regardless of how talented he is.

Discipline and earnestness ... Some things never change. Even later in New York, I was no less strict with myself, no less focused on continuing to get better and better. This same discipline I had suffered from as a child was something I had also made a habit of in my second life. Never slacken the reins, otherwise it all goes awry, and a lack of discipline is punished with an extra shift – the fact that you overdid things last night is an excuse, but doesn’t exonerate you, so get the violin out, make yourself an espresso and get going; it’s time to spend the next three hours practising.

Looking back, I tell myself I would never have reached my current level of violin-playing without this pressure. Every other world-class performer will confirm that it is only the relentless pressure of expectation that leads to success. Today, I know that most things were right, even though there was also a lot wrong. But that’s reason talking. My subconscious insists on a different, less comfortable version of the story. And that’s why it’s still not easy for me to open this door and step into the big, dark room where little David sits with his parents. He’s four years old at the time, and near him, bathed in the golden light of the spotlight, there is a man dressed in black, holding a violin.

You can find videos and photos for this chapter here.

This impossible instrument

With my father, on one of the first times I ever tried playing the violin

Do I really remember it? Or am I simply recalling the memories of others? I think I do remember ... Szeryng was going to perform in Aachen in 1985. Polish-born Henryk Szeryng, one of the greatest violinists of his time – and I would soon be able to see and hear this hugely acclaimed man in my hometown. Incredible! Being just four years old, of course I had no idea how lucky we were, but my father was adamant that we should go. So we bought our tickets, quite near the front, to be as close as possible to this Henryk Szeryng. But one thing first had to be clarified: should we take our youngest child with us? Will he be able to sit still for so long? Will he whine? My father made the executive decision: ‘David is coming. He needs to listen to this.’ Worst-case scenario, my mother would have to take me out of the auditorium.

That night, I sat between my parents in the fourth row of the Eurogress concert hall, and, as Szeryng played, I started imitating the violinist I was watching up on stage – playing air violin, so to speak. I guess it must have looked pretty weird. Szeryng certainly noticed there was a child down there playing along, and, in the breaks between pieces, he would look at me and actually wait until I had calmed down again and was sitting still before nodding at the pianist and continuing to play.

After the concert, he came back on stage to play an encore. That’s pretty standard. But what happened then, wasn’t at all. As the applause died down, he stepped to the front of the stage, pointed his bow at me and said, ‘When I was the same age as this little boy in the fourth row, I listened to Fritz Kreisler in concert.’ Kreisler was a violinist from the 1920s and ’30s, of the same calibre as Szeryng. ‘Kreisler’, he continued, ‘saw me in the audience and dedicated his encore to me at the end, namely Tempo di Minuetto, which he had composed himself. And tonight’ – he looked at me again – ‘I am playing Tempo di Minuetto by Fritz Kreisler for you, young man.’ This Tempo di Minuetto is a heartbreakingly romantic piece, a sweet little lullaby for a little prince, and he played it for me. Perhaps this moment was the initial spark. In any case, it wasn’t long before my father pressed my first violin, a little child’s violin, into my hands.

The violin is a curious instrument. Maybe this is something I should save for later, but then again I absolutely have to talk about it now, because – what would I be without my violin? I have asked myself this question again and again throughout my life, trying to imagine a life without a violin, and I haven’t been able to, because I’m violin-obsessed. I just love violins; they have an irresistible allure for me, and not only because of the music – it’s the violin itself that has me hooked, because I have experienced too much with it; the awful and the amazing. And anyone wanting to understand me needs to understand this instrument before embarking on my life journey with me. So for anyone who has never played a violin, I want to briefly explain what makes it different from other musical instruments.

If you want to make music, there are basically four different ways of creating sounds (leaving aside the human voice for the moment). You can press air through holes, in which case the sound is determined by keeping some holes shut and others open – that’s how flutes, trumpets, clarinets and organs work. That’s method #1. Or you can strike an object, whether with your fingers or with sticks or mallets – this is the case for pianos, drums, triangles and xylophones, and it’s method #2. Then you can get strings to vibrate by plucking them, such as with guitars or harps. That’s method #3.

Bowed instruments such as the violin and cello add a fourth option to this repertoire. It can be described as rubbing/friction, scraping or scratching, and doesn’t really sound like a promising way of producing melodious sounds. As the word ‘scratching’ implies, this method can produce sounds, but very rarely are they nice ones, and so begins the torment of the young violin student.

There is probably no worse instrument for a beginner or, in fact, anyone living with or near them. Learning to play the violin requires nerves of steel from everyone involved. Even my father’s nerves must have been shot after a while. And we haven’t yet even spoken about the actual problem, namely intonation – that is, the process of actually finding the right note on your violin.

Let’s compare it with the piano. Provided the instrument has been properly tuned, I only need to press down on a piano key to promptly get the note I want, pure and undistorted. Any small child can be taught to play a clean C-major chord on a piano within seconds. Achieving the same on a violin takes months. Why? Because a piano serves you every note on a silver platter; you have a keyboard about two metres long, with keys on top that are so wide it’s hard to miss them even during an allegro furioso. On a violin, however, the notes are not defined. You can’t see them with the naked eye; you have to find them blindly. It’s a case of millimetres, even micro-millimetres, often within milliseconds! Instead of a two-metre-long keyboard, you have only a short fingerboard that packs in the entire range of notes over a few centimetres, meaning that the individual notes are all tightly crammed in next to each other. It is a mystery how, given these conditions, and often at lightning speed, anyone is ever able to hit a clear, sharp and clean-sounding note.

As if that weren’t enough, when you have hit the note, you still haven’t actually produced it. No sound comes out, because there is no friction. It is only once the bow is used that the violin comes to life, which brings you to your next problem, namely that of having to perform movements with your right hand that are completely different to what the left hand is doing. Your left hand is feeling its way along the strings more or less nimbly, while the right is performing upward and downward motions – at a completely different pace – with a bow. Well, now try coordinating these two movements! Not to mention the fact that, using this bow, you have to pinpoint the ideal spot between the bridge and fingerboard; in other words, that section of the string that gives you a smooth, round sound. You have to find this exact ideal point for every single note, and if you’re looking for it in the same section of the upper string as it is on the lower string, you would be wrong – it’s in a different place at the top.

To cap it all off – and this is where I will leave things for the moment – no physiotherapist would ever have invented such an instrument. Pianists have to be a bit careful of their backs, it’s true, but a violinist needs to expect leg and back twinges after two hours, because they are forced to contort their bodies. After all, the violin needs to be held somehow, so you’re standing there with your head turned to the left, the left shoulder slightly raised and the instrument clamped between your shoulder and chin. While the left hand offers a little support, it is also needed for acrobatic finger movements and therefore needs to be able to move freely, so holding the violin from this side is out of the question. What this means is that, on top of all the technical challenges associated with playing the violin, the body and violin also need to work together perfectly.

In short, it is a nearly impossible instrument. The degree of difficulty is brutal, and the prospect of becoming an elite violin player as likely as scaling Mount Everest alone without oxygen. So now comes the totally justified question: why would anyone encourage helpless little four- or five-year-olds to take on the struggles associated with this instrument?

The answer is: because experience has shown that, at later ages, the head and hands are no longer up to the task of handling the violin’s tremendous demands. Someone who starts at age ten or twelve won’t necessarily be a bad violinist, but they will never reach the summit of Mount Everest. Perfectly hitting a string with a finger of the left hand with millimetre precision is a fine-motor feat that can only be learned very young, and it’s a similar story for developing a skilled ‘ear’. Not even the best concert violinist in the world can hit every note exactly right one hundred per cent of the time. They will constantly have to make corrections within a fraction of a second, and these tiniest of corrections require an extremely precise ear trained all the way from childhood. So it’s better to start when the brain is still able to absorb everything like a sponge, when every grip can still be imprinted into the subconscious. My father was right in this respect. No brilliant violinist, no world-famous pianist began playing their instrument as late as the age of eight or nine, and my father was probably envisioning an international career for me very early on.

For the time being, however, little David is standing in the living room of his parents’ house in Aachen, grating away on his Suzuki fibreboard violin, making noises that, even to him, sound horrendous. For now, he has to learn to live with something that is torture for his ears. Thank God I can’t remember my earliest beginner days. I can imagine the strain it puts on the nerves of everyone involved when I hear young people who are just starting out. It’s so much more enjoyable when someone is learning to play the piano! The violin’s fun factor is more or less zero; for months, sometimes even years, you produce nothing but rubbish, and yet you still have to persuade yourself to keep going – every single day. Where, from what corner of the universe, does a child find his or her motivation in such circumstances?

You can find videos and photos for this chapter here.

A childhood with violins

At age five

It’s significant that even my earliest memories involve a violin. I cannot recall ever not having one in my hands. It’s as if music is what brought me into the world, as if it was the Big Bang that created me as a thinking being.

But I’m not the only one standing here in the living room with a violin, doing my best to convert my father’s instructions into sounds. Standing alongside me is my older brother, Alexander. I am five and he is seven, naturally a more advanced violin player than me. Still, I am probably the happier of the two of us. Most definitely, in fact. When my brother was given his first violin as a gift a year earlier, I was envious because he had this great new toy – I wanted a violin like that too! Now I finally had one and could emulate my sibling and role model. All my dreams had come true, because there is a huge difference between whether ‘you should’ – as with Alexander – or ‘you can’ – as it was with me. He had to learn to play the violin, whereas I wanted to. Obviously I didn’t have any idea what was in store for me, but I was certainly motivated.

So the two of us are now standing in the living room with our miniature violins, listening to our father teaching us by means of the Suzuki group-teaching method, which was the rage at the time. And for the next fourteen years, effectively every day in the Bongartz household will revolve around violin-playing.

My father, Georg Bongartz, is a qualified lawyer but a violin auctioneer by trade, and thus a violin expert. My mother is American-born Dove Garrett, a prima ballerina, who is responsible for organizing this not uncomplicated household. For the time being, my name is David Christian Bongartz. My sister Elena will become a new addition to our family many years later. Apart from violins in particular, my father’s passion is music, especially classical music. He also has practical experience of it, having played in the German Air Force’s entertainment orchestra and occasionally been a drummer at military funerals. Ideally, he would have become a violinist – that was his dream, but a career as a soloist was just a little out of his reach, and instead he turned his hand to trading in stringed instruments. Alexander and I were not his first violin students either; he had taught other children before us, so we could actually learn a lot from him.

And we did – but at what cost! Let’s put it this way: as a child, you’re on your parents’ leash, but some leashes are long and some are very, very short. My father discovered that both his sons were remarkably talented violinists – me maybe a little more than my older brother. So what do you do with that? What measures do you take once you’ve realized fate has placed two golden eggs in your nest? It’s not an enviable situation, because you’re suddenly responsible for ensuring that birds of paradise, not quails, hatch out of those golden eggs. So are you going to just stand by and watch these talents go to waste? Or are you going to leave no stone unturned in your quest to secure this treasure?

My father decided to leave no stone unturned. Circumstances played into his hands, because he worked from home. He was basically always around and had a lot of free time. He gave us lessons, assessed our progress, provided criticism and didn’t let up, always expecting more, even better performances, even greater progress. He became less of a father and more of a teacher by the day – a teacher who demanded discipline, hours and hours of regular practising, and tangible success. If we fell short of his expectations, the atmosphere at home turned sour. Everything was done according to his wishes, and he had very specific ideas – this is the fingering, this is the bow stroke, this is how you have to play it, and this is how it has to sound. The pressure never let up, and a year after I started, Alexander gave up.

Because he was bad at it? Definitely not. He was unhappy, absolutely miserable. He had completely lost interest; I would often hear him crying while practising. He was also barely able to cope with playing in front of people, at our house concerts, when other parents were also watching; he was plagued by stomachaches beforehand and his face would be white as a sheet when he stepped up to perform. He eventually mustered up the courage to tell my father, ‘I do want to play an instrument, just not the violin any more. I’d prefer the piano.’ The piano was not my father’s greatest passion, but Alexander got his wish and had his freedom back.

This could also have been my time to jump ship – but why did I stick to the violin? Because I was more stubborn than him, or had a thicker skin? Or did I have strong desire to please? That’s probably more like it. I wanted approval from my father and my audience, and I definitely didn’t want to fall short of their expectations. My need for harmony made me tolerate any ordeal. This need was both a blessing and a curse; above all, however, it would be one of the reasons I didn’t fall to pieces over the coming years.

Because many do fall to pieces. Achieving a great career isn’t just about talent alone; your personality, your motivation and your resilience are just as important. What you experience as a promising musician in your early years contradicts any notions you may have of a carefree childhood. You’re basically a pro at a very young age, and are treated as such: as someone who does work that must meet the highest of standards. My brother was smart enough to pull the plug in time; my need for harmony was what saved me. But many others fall to pieces.

From then on, my father concentrated on me. He would be my main teacher until I was seventeen, and, over the coming years, violin-playing would develop into a twenty-four-hour job for me, meaning, of course, that father and son were working together 24/7. Plenty of time to squabble, because family life and work were now inseparable. Time and again I found myself sitting in my room at night thinking, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore, I can’t do it anymore – ditch the violin, screw music ...’ Except that was impossible, because my family’s happiness, the atmosphere at home and, of course, my own wellbeing, my own peace of mind, all depended on how well I played the violin. If I practised diligently, if I achieved my targets, it was a harmonious day; but if I slackened off, there was tension, my father would get annoyed and twitchy, and everyone suffered. So not only was I responsible for my progress on the violin, it was also down to me to create a pleasant atmosphere in my family home.

That put a strain on me. On days when no one at home was in a good mood and I myself was thoroughly miserable, sleep would be out of the question until I had made my peace with the violin. Then I would say to myself ‘it can’t be that hard, you’ll manage it’ – and, while everyone else was asleep, I would creep out of my room and down the stairs, take out my violin, not even turning a light on, and keep practising in the dark. I had to play in order to sort out my emotions. For me, at least, the day that was now almost done would have a harmonious end.

So me being a fast learner and making amazing progress was also due to the fact that, unless I was surrounded by harmony, I would keep working. I worked until everyone else was happy again. But this time left its mark on me, because, as a child, you want to be protected by your family, you want to feel safe and loved and cared for. But if this experience becomes overshadowed by being constantly under strain, relentlessly exposed to pressure and tension, and incessantly forced to perform exceptionally, that’s when pain sets in. That’s when your self-esteem suffers. That’s when the sword of Damocles of inadequacy and failure constantly hangs over you. Even though everything ended up right, there was a lot that was wrong then.

You can find videos and photos for this chapter here.

Exceptional circumstances

There’s nothing better than a relaxed day in the snow (with my brother Alexander)

Did I suffer? Yes, of course I did. But did my father make me a slave to the violin? No, absolutely not. It’s not as if I was being condemned to child labour in a coal mine – I was making classical music, the most magnificent music on earth. This music is grand and overwhelming, but equally difficult and intangible, a glimmer of joy in the distance if you settle for mediocrity, but an explosion of blissful emotions within yourself if you work towards perfection.

No, it wasn’t out of fear of my father that I demanded the most of myself. Naturally, no child likes uncomfortable silences at the dinner table, and they feel even more awkward when they are the reason for this silence. But my tenacity back then was driven by my love of music. Even as a child, I just knew that music was the one great purpose and meaning of life. So no matter how dejected, how desperate or exhausted I was, music always took me in its arms, consoled me and made everything right again.

And every time, I knew I would be able to achieve what I expected of myself. I knew what was possible on the violin. Even as a child, I listened to any classical music recordings I could get my hands on. Browsing through Media Markt and coming out with five new CDs by great violinists would never fail to make my soul leap with joy. I devoured music the way other parents’ early-maturing children perhaps devoured works by their favourite writers. I wasn’t a bookworm; I was a record- and CD-worm. At home, I listened to these records over and over again and got goose bumps – I can’t begin to describe what those hours of pure joy did to me.

And that’s why my allies weren’t literary figures, nor heroes from novels or movies. My allies were the great composers of history – Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Beethoven, and of course Bach. But, and this is the crucial bit, they spoke to me through great interpreters, through people like Heifetz, Oistrach, Menuhin, Zukerman, Perlman and of course Szeryng and Kreisler. These incredible, phenomenal violinists – they were my ultimate heroes and idols. It was them I listened to, sitting by our stereo in Aachen; it was them I one day wanted to emulate, delighting my audience with my playing just like they were currently doing to me. In short, I wanted to become a magician. An enchanter.

Apart from that, there were more banal reasons for me to keep enduring this life of mine. One of them is that what you experience at home as a child seems normal to you. Even if you were to grow up in a cellar and never come out, you wouldn’t question your circumstances because you simply wouldn’t know any different. So for me, my life was normal, and, in fairness, I have to say it could have been a lot worse.

There were times I nearly forgot about the violin, such as when I would go on bike rides in the area surrounding Aachen with my father, or when I would play badminton in our garden with my brother. As a child, I was a ball of energy, and if I wasn’t holding a violin, I had to get outside, away from it all. I romped around the garden like a tornado and was as adventurous as anything. My brother was the quiet, more level-headed one; I was extroverted and full of joie de vivre – at least until it was time to head back inside and practise again.

Then there was school. And even my schooldays seemed semi-normal to me, despite my circumstances being constantly exceptional.

My mother managed to obtain official permission that allowed me to attend Elementary School only four days a week. Thursday at noon would be the end of my week – but of course I didn’t have free time after that. The extended weekend was spent having lessons with whoever my violin teacher was at the time, and many of them lived hundreds of miles away. Later in middle school and high school my mother obtained official permission for me to be privately tutored until final exams which enabled me to receive my high school diploma. That was a relatively laid-back affair: sometimes it would be five hours a day, sometimes only three, and occasionally none at all, because, for example, I would have to make a quick trip to Miami to see a famous violinist. And by quick I mean ten days.

Was I a lucky chap? I don’t really know; my education was quite patchy for a long time, but the fact is that the violin was much more important than school. Most parents will check that their children have done their homework, but not in the Bongartz household – if I had practised well, no one gave a damn about homework.

As you can imagine, that casual attitude to my education frequently left me feeling embarrassed. I would often quickly scribble something in my notebook just before class – rarely the smartest thing to do – and my primary-school teacher would occasionally take pleasure in loudly sharing my notes with the rest of the class – or even writing my muddled sentences, complete with spelling mistakes and incorrect grammar, word for word on the big blackboard. Fortunately, that only happened once, but I felt thoroughly ashamed often enough. And while I barely scraped my way through school, my brother was a brilliant, straight-A student, which didn’t exactly help matters.

Coupled with this was the fact that my classmates obviously found it difficult to make friends with me, and the feeling was mutual. My repertoire of conversation had nothing in common with that of other children my age. Honestly, I couldn’t talk about the things my peers were talking about, and was the only one to be substituted in just a minute and a half before the siren when playing football in the schoolyard during lunch breaks. It wasn’t because of my lack of sporting ability; it was just that no one wanted to have ‘that violinist’ around. That weirdo who knew nothing of real life, who ran around in his brother’s hand-me-down pullovers and corduroy trousers, and, to cap it off, was exempt from any physical-education classes for fear of injuring his precious fingers.

In fact, I never worried about my fingers. My father did, though – that’s why I wasn’t allowed to play games that entailed throwing a ball. Even school excursions and youth hostels were things I only heard about through my brother. Every time my class went on a trip, I had to miss out. Skiing holidays were strictly forbidden, because at least one participant would always come back with their arm in a cast. But I still got involved in little fights because I would cop a lot of banter for my violin, and also I would defend the innocent, primarily girls, who were nudged and teased and had their hair pulled. Bullying was against my morals, and as I was very tall even at a young age, I pushed back. I certainly made a point of ensuring justice in the schoolyard, regardless of my fingers. As an outsider, you have to make a valuable contribution to society somehow, after all.

In other words, elementary school and playing the violin is a tricky combination. And if, on top of all that, you don’t leave the coolest of impressions, if even your appearance and the way you express yourself are completely out of place in a primary school, then ‘outsider’ is a term that barely comes close to describing your role in Aachen school life. If someone had to draw the word ‘uncool’, they might as well have just put a photo of David Christian Bongartz there. But, honestly, even then, my involuntary special status didn’t really bother me. After all, I had my own circle of oddballs, namely violin students my age whom I met at my teachers’ houses.

You can find videos and photos for this chapter here.

Bring on Tchaikovsky

With my teacher Zakhar Bron

It wasn’t long before my father felt he needed support, and he began looking around for a good violin teacher. Later on, I was to have the most amazing violinist, a living legend, as a teacher, but even for a wunderkind, learning to play an instrument is a step-by-step process, and my list of tutors starts with Coosje Wijzenbeek. She was Dutch, and her name was pronounced in such a way that, even for child, it ran easily off the tongue: ‘Koshe Weizenbek’. Known for successfully teaching small children, Coosje Wijzenbeek in Hilversum would be my teacher for now, from the age of four to six.

What I remember most are the car rides to Hilversum at the weekend. My brother was initially there too, so the backrest at the back of the car was removed to allow space for us to sleep – my father found this preferable to us fighting in the rear seat, which would have been the alternative way of whiling away the travelling time. With Coosje, I worked on the basics: practising scales, playing easy studies and performing mini student concerts. But, even back then, the pieces could not have been that simple, because at the age of five, I had already come first in the Jugendmusiziert [Youth makes music – a competition for children and adolescents on a regional, federal and national level in Germany] music competition with Beethoven’s RomanceinFMajor. So my rendition of this romance, a not entirely unchallenging piece, must have sounded at least half-tolerable.

It’s possible that, even with Coosje, my father made the point that his son didn’t like spending all his time on studies and finger exercises, but also enjoyed playing serious compositions. After all, his great idols – Menuhin, Oistrach and Heifetz, all of whom were also child prodigies – started performing great works at just six or seven years of age. A ten-year-old Menuhin was on stage playing Beethoven’s violin concerto, while at the age of eight Heifetz performed Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto with an orchestra – in other words, a high bar had been set for me.

I also remember meeting Janine Jansen, who would later similarly go on to have a great career, at Coosje’s. But the rest of my memories of this time are hazy, because I didn’t spend long taking lessons in Hilversum. After a year and a half, my father decided I had outgrown my first teacher, and set about finding a new one.

It is worth pointing out here that my father always sat in on every lesson with Coosje and indeed with all the other childhood teachers yet to come. He would initially note everything down on the spot, but later switched to recording every lesson with a small video camera, so he could go through and analyse it meticulously at home. So my father was effectively continuing his own learning with my teachers, himself playing the student, albeit also acting as a supplementary teacher during the week, thereby exercising complete control over me and my musical development. There was no downtime for me, particularly as he also had to drive me to and from lessons – yet another opportunity for him to once again go through everything point by point.

From then on, I would go twice a week to Saschko Gawriloff, without my brother, who was now totally finished with the violin. Gawriloff taught at Cologne’s College of Music, was himself an acclaimed violinist, concert master and soloist, and was thus the perfect choice to expand my musical repertoire. What I, as a seven-year-old, particularly liked about Gawriloff was that this likeable, warm-hearted and highly skilled man opened his doors to a little boy like me. I even felt comparatively comfortable in his home. I would arrive in the early afternoon, we would spend an hour working together, he would get me to stop for an afternoon nap, and then we would continue.

I had of course long moved on from my Suzuki child’s violin. During those early years, children grow out of their violins as fast as they do their clothes. I started with a 1/16-size violin, which wasn’t much bigger than an adult hand. By the time I was with Coosje, I had already moved on to a 1/8, a Hornsteiner, a very fine instrument indeed. My violin during the Gawriloff days was a Jombar, produced by a French violin-maker in the late 19th century, varnished in a glorious red.

Not only did my teachers want me to succeed, they expected me to succeed, and these successes had to be tangible and demonstrable. Gawriloff, for example, primarily honed my mastery of the instrument, my intonation, my vibrato, how I held my bow. That’s what the études he had me practise were for – violin compositions comprising a terrifying array of difficult and fiddly exercises for both hands. Playing études is simply fine-motor tuning; boring repetition to get the fingers and brain into shape. While Gawriloff made me do this cheerless task, he did know that practising also needed to be fun, which is why he never forgot to give me something enjoyable: a little piece by Handel, an early sonata by Mozart, a Dvořák sonatina. Getting the hardest stuff over with first, then having fun and playing something beautiful is the ideal balance. That’s what any good teacher should do, and the friendly Gawriloff was a very good teacher – just like all the other teachers I’ve had in my life. Some were strict, but no one ever shouted or was short-tempered. I felt totally comfortable with all of them, and enjoyed working with every single one.

However, I did make their lives pretty easy, because I’m a teacher’s pet. I would never wait to give them a chance to criticize; I would cut them off, saying ‘I know what you’re thinking’, and then play the same passage again, but better. Heaven forbid any teacher should think I hadn’t noticed the weak areas ... The truth is, I craved encouragement and recognition. I couldn’t expect praise for a grade-three school essay filled with spelling mistakes and scribbled down barely half an hour before, but, when it came to playing the violin, I was good, I sought enthusiasm and was happy to help draw it out a bit.

Okay, now that I’ve made that admission, it’s time to move on to my third teacher. By the age of eight, I had reached a good technical level, and my father had heard about a Russian music teacher from Novosibirsk who had come to Germany. His name was Zakhar Bron, he had a reputation of being an excellent teacher and, in the little world of ambitious parents, the news of his arrival spread like wildfire.

How can you tell if a teacher is excellent? From their amazing students. Bron hadn’t come from Siberia on his own – he had brought brilliant students such as Vadim Repin, Maxim Vengerov, Natalia Prishipenko and two or three others, all aged between ten and fourteen. Only Bron himself knows how he managed to get visas for all of them from the Soviet authorities, but they were now all in the West, where everybody was raving about the man who had students the likes of whom had never been seen before.

The news of Zakhar Bron’s spectacular talent academy had piqued my father’s interest, and he decided that this Bron would replace Gawriloff as my teacher. He managed to get me to play for Bron, and at the age of eight I joined his group of students in Lübeck. This marked the start of a hugely exciting, eventful time, packed full of proper, great music. My father and I would start heading to Lübeck on Thursday evenings, him at the wheel and me putting one classical music CD after another into the CD player – I would take a stack so large it would have lasted a trip to Portugal and back. We would ride a wave of the most wonderful music, played by the greatest artists in the world, to Lübeck every two weeks.

Our repertoire contained not only violin concertos, but also operas, chamber music, piano concertos and all manner of symphonies – though sometimes, after barely five minutes, we would both agree that this or that piece was not worth listening to and didn’t appeal to us at all. It was on those highways that I experienced the most enjoyable times with my father – the music united us, made us like-minded, made us father and son.

It was just as nice, if totally different, to make this trip with my mother. If my father could not be available, she would get behind the wheel and the two of us, or three of us if Alexander came along – and later there would even be four of us, because my sister Elena was born in the meantime – would head to Lübeck. We rented an apartment, cooked dinner at night, and thus briefly created a homely atmosphere, an unusually relaxed family life, in the faraway city of Lübeck. I would spend three days working with Bron, and progressed faster than I ever had before.

Just as my father had thought, Bron’s mission was to get his students playing the great works by the great composers as early as possible, and, that same year, he said to me, ‘Let’s try the second and third movement of Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto.’ We avoided the first movement of that concerto for the time being; it was super-complex, and was long considered unplayable in the 19th century. But Bron was confident I could handle the second and third, because he knew about my finger skills.

He would constantly feed me pieces that allowed me to shine technically – compositions such as the ‘perpetuummobiles’, short but breathtakingly fast pieces in which the violin is not still for the entire three minutes, racing to a furious end in semiquavers and demisemiquavers. Anyone who was able to manage that would not have any problem, at least at a technical level, with the last movement of Tchaikovsky’s concerto. And I managed them – first the PerpetuumMobile by Czech composer Nováček, and soon after the MotoPerpetuo by Paganini, both extreme examples of virtuoso violin music.

So, bring on Tchaikovsky’s concerto! And, after I had mastered movements two and three, Bron even allowed me to tackle the lofty peak that was the first movement. Astonishingly, I scaled it relatively quickly, and, at the age of ten, I was able to play that virtuoso first movement without any major difficulties.