Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

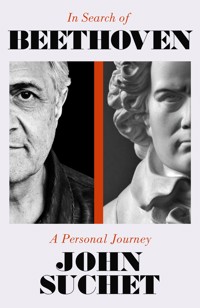

A PRESTO BOOK OF THE YEAR 2024 'From palaces to warzones, John Suchet goes on a Beethoven odyssey' The Daily Telegraph 'This personal account of his life-long passion has an appealing light touch' Financial Times Best Books of the Year 'This is a wonderful tale of self-realisation, of what we can gain from turning to genius in life's many crises.' Norman Lebrecht, author of Why Beethoven From the bestselling author of Beethoven: The Man Revealed, In Search of Beethoven is John Suchet's latest and most personal book dedicated to the life of this extraordinary composer. Part biography, part memoir, part travelogue, Suchet draws on his own life and career as a foreign correspondent and news anchor to show how Beethoven's music has accompanied him through the best and worst of times. It was with him as a music-loving and adventurous teenager, as a journalist entering Beirut in the grip of civil war, and as he has continued to explore the old cities of Bonn and Vienna, in search of the man behind the music. In this novel and compelling book, we see Beethoven brought vividly – and sometimes painfully – to life. Suchet traces Beethoven's footsteps from his early years in Bonn to his dying days in Vienna, taking us on a journey both literal and symbolic, as he uses his own experience as a Beethoven aficionado to demonstrate the life-changing power of great music. 'This is a comprehensive yet accessible history of Beethoven wrapped up in an inviting, immersive tale of adventure and discovery, delivered in an inviting, engaging and endearing way typical of this master storyteller.' Debbie Wiseman OBE, composer and conductor

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 430

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for In Search of Beethoven

‘This book has had a profound effect on me. Suchet has brought Beethoven to life. Anyone and everyone will gain something from it – musician, music-lover, historian, even gossip-lover. I read it in one sitting. I want to fly off to Vienna immediately.’Carol Barratt Hon RCM GRSM ARCM, Pianist and Composer

‘John Suchet’s unusual combination of biography and autobiography is full of fascinating details about Beethoven’s life, conveyed with enthusiasm and imagination, but cleverly dovetailed with personal reminiscences.’Professor Barry Cooper, University of Manchester, Author of Beethoven: An Extraordinary Life

‘John Suchet lives with Beethoven, learning something every day. This is a wonderful tale of self-realisation, of what we can gain from turning to genius in life’s many crises.’Norman Lebrecht, Author of Why Beethoven

‘John Suchet weaves into the narrative his own experiences as a foreign correspondent and news anchor to create a compelling and moving account of events which are inextricably linked with Beethoven’s struggle with destiny and the ensuing path to victory and emancipation that almost always bring many of his works to a triumphant close. This is an indispensable book for every Beethoven enthusiast as well as for every performing musician.’Dr Marios Papadopoulos MBE, Music Director, Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra

‘John Suchet’s account of his own difficult times, and those challenges which the composer faced, are brought to life by the author’s incredible skill, drawing on his years as a frontline journalist with an acute eye and ear for detail . . . A gift for any Beethoven fan!’Sandra Parr, Artistic Planning Director, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic

‘As always, John Suchet’s diligent and persuasive detective work throws new and fascinating light on seminal moments and aspects of Beethoven’s life . . . an excellent and eye-opening read.’Howard Shelley OBE, Pianist and Conductor

‘You can’t help but be swept away by John Suchet’s infectious enthusiasm, as well as being mightily impressed by his almost unquenchable thirst for knowledge about his musical hero. This is a comprehensive yet accessible history of Beethoven wrapped up in an inviting, immersive tale of adventure and discovery, delivered in an inviting, engaging and endearing way typical of this master storyteller.’Debbie Wiseman OBE, Composer and Conductor

ALSO BY JOHN SUCHET

Beethoven: The Last Master (Trilogy)The Friendly Guide to BeethovenThe Treasures of BeethovenBeethoven: The Man RevealedThe Last Waltz: The Strauss Dynasty and ViennaMozart: The Man RevealedVerdi: The Man RevealedTchaikovsky: The Man Revealed

For my darling Nulawhose idea this book was.

Contents

Preface

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

References

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface

In July 2022 my wife Nula and I were in Vienna, for no other reason than it is a city we both love. Nula honeymooned there with her late husband James. I visited it several times with my late wife Bonnie, researching my earlier Beethoven books.

A planned Danube music cruise I had been due to host fell victim to the global Covid lockdown of 2020, and the hotel in Vienna I had booked for a few days’ stay at the end of the trip kindly held my deposit for two more years until we could finally make it.

Nula’s James, a TV documentary writer and director, was passionate about Mozart. He had written a six-part TV series called The Family Mozart, which was due to go into production when he was diagnosed with dementia in 2004.

My Bonnie succumbed to the same appalling disease, diagnosed in 2006. Both James and Bonnie were in the same care home, in adjacent rooms, which is how Nula and I met. A friendship developed and, nearly two years after losing our spouses, we married. Nula found that she had exchanged a husband with a passion for Mozart for a husband with an equal passion for Beethoven.

James had taken her round all the Mozart sites in Vienna, relating the story of the composer’s life. In Vienna with me on that July visit, she asked me to show her the Beethoven sites. The most important of these is the small cottage in the village of Heiligenstadt in the foothills of the Vienna Woods where, at the age of thirty-one, realising his deafness would inexorably worsen, Beethoven wrote his Will. Now in a suburb of Vienna and easily reached on the U-Bahn, the cottage has been tastefully restored. We walked round it, then sat on a bench in the garden. Trees and plants were in full summer bloom. I talked – on and on and on.

‘You must write all this down,’ she said.

‘I have already, several times,’ I said, laughing.

‘No, do it differently. Make it personal,’ she urged. ‘Listen to the passion in your voice. Walk in his footsteps. Eat and drink with him. This will be your Beethoven journey.’

1

At 5 p.m. on 26 March 1778, a stocky, powerfully built man walks out in front of a small audience in the Sternengasse in Cologne. He is dressed smartly but uncomfortably. He might have borrowed the frockcoat and breeches: they do not fit properly and look out of place on him. His abundant dark hair is scraped back and a thin pigtail falls across his collar. There are pockmarks on his face.

But it is his eyes, open wide and blazing, that command attention. His jaw is set. Intensity and determination emanate from him, accentuated by the clenched fists at his side. The leonine head is thrust forward as he opens his mouth to speak.

‘I am Beethoven,’ he says, ‘and it is my honour to present my student, Mademoiselle Averdonck, contralto singer at the princely court in Bonn. She will sing several beautiful arias. She will be accompanied at the piano, after which there will be several pieces played on piano alone. These will be performed by my son, who is greatly accomplished even at the age of six.’

Mademoiselle Averdonck, smiling, ushers the small boy out in front of her. Ludwig van Beethoven, aged seven not six, is about to give his first public performance.

Precisely forty-nine years later, to the day and the hour, as a storm breaks over Vienna, the most celebrated composer and musician in the world is about to draw his last breath.

2

I was sitting high up in the gods at the Vienna State Opera for a performance of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio. Those punchy opening chords of the overture hit me like a wall of sound. The curtain rose; the singing began. The next thing I heard was a very different wall of sound – thunderous applause and cries of ‘Bravo!’ The curtain had fallen. It was 1961 and I was seventeen. I had slept through the whole thing.

Twenty-three years later, at midnight on Thursday, 8 March 1984, I stood at the railing of a passenger ferry as it pulled away from the dock at Limassol in Cyprus and turned east for the overnight journey to Beirut, capital city of a country in the grip of civil war.

I was one of only two passengers on board. The other was a Danish businessman. Beyond initial salutations we did not speak again. We knew that what we were doing was madness. Any sane person would be heading in the opposite direction.

The air was crisp and fresh, the saltwater spray invigorating. I imagined the sweet exotic scent of the Middle East, although we were still some way out from Beirut. Four hours later, in the twilight of dawn, I could see a distant red glow. My stomach churned with a mixture of fear and excitement. I was an ITN reporter, en route to join my camera team, who were already in the city. I was on one of the biggest stories in the world.

I reached into my anorak pocket and pulled out my battered Walkman. In the other pocket was a single cassette tape, the only one I had with me. Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, the Eroica, played by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Herbert von Karajan. I blew the sound into my ears. When it finished, with that gloriously affirmative upward rush to the final chords, I played it again. And again.

What had happened in that intervening quarter-century, between a Fidelio that had floated past my unhearing teenage ears, and the Eroica on that night-time sea voyage, an Eroica that lifted me up and filled me with confidence and determination in the face of fear and uncertainty?

The Fidelio I slept through was the culmination of a trip to Vienna and Salzburg organised by the Anglo-Austrian Friendship Society. I cannot recall how I found out about it but I do remember pestering my dad relentlessly to let me join, even though the cost was £25. I also remember being chosen, as the most proficient German speaker in the group (recently awarded a prize at school for my prowess in the language, the only academic accolade of my entire school career), to deliver a short speech of thanks to the Mayor of Vienna in the ornate Gothic Town Hall on our final morning.

‘Don’t worry,’ said Mr Black, our team leader, the night before. ‘It’s only four or five sentences long and I’ve written it for you. All you have to do is read it.’ I stood by my bed till well after midnight learning the words. I was determined to deliver it from memory.

The next morning, with the piece of paper reassuringly in my pocket and a cold trickle of sweat running down my spine, I managed to deliver it without a stumble to a mayor who was rather impressed (as was Mr Black). Unfortunately for a permanently crowded brain, I can still remember it, word for word, more than sixty years later.

At the age of seventeen I was in my ‘Tchaikovsky phase’. What had turned me into a teenage Tchaikovsky obsessive? One school summer holiday, not long after the Vienna trip, I got a job selling records at the flagship HMV store in Oxford Street in London. The manageress, a Miss Forrest, asked me which department I wanted to work in. ‘Classical music, please.’ She put me in rock and pop.

In a lunch hour I went upstairs to the classical music department and leafed through the letter T, Tchaikovsky being the only composer whose tunes I could whistle. I bought an LP of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4, played by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, primarily because I liked the cover. It showed a Russian couple in traditional rustic costume, and I had just begun to learn Russian at school. The music captivated me from the first time I played it. I wore the record out on my box gramophone. That opening call on French horns and bassoons!

I followed it with an LP of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, Alfredo Campoli the soloist. It had a similar effect on me. At Chappell’s music store in Bond Street I found a score of the solo part of the Violin Concerto, and also a book of Tchaikovsky’s favourite melodies arranged for Grade Three piano.

Back at school I proudly presented the piano book to my piano teacher. ‘Why Tchaikovsky?’ he asked. ‘You’ll grow out of it.’ I was shocked. Could he be right? I wavered, metaphorically losing my musical balance, unsure which way to fall. The coup de grâce was delivered by my violin teacher, who found the solo part of the Violin Concerto in my music case. ‘That’s a bit ambitious, isn’t it?’ she said, thereby killing my enthusiasm for the violin in a single sentence. I sought solace by teaching myself the more forgiving trombone and indulging a different kind of musical passion, trad jazz.

The demotion of Tchaikovsky from the number one spot in my classical music affections created a vacancy. I tried Bach – too much the perfectionist. I explored Mozart – sublime, but where was the passion? Mendelssohn – pretty. Sibelius – dark. Simplistic, I know, but I was a teenager.

It would be so nice, so neat, to be able to say there was a single revelatory moment, the musical equivalent of a blinding flash of light, when I heard Beethoven and it changed my life. The fact is, Beethoven crept up on me. What I certainly do remember is a period in my life in the early 1980s when I was going through a difficult time. My marriage was unravelling, and my professional life wasn’t going too well either. The two were clearly connected, though I struggled to see it at the time.

I had a newfangled cassette tape player that you could carry in your pocket and listen to the music through tiny earbuds. No more 12-inch LPs that warp and scratch and styluses that go blunt. I bought a single cassette tape. I cannot remember where I bought it or why I chose Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. But it was about to become the soundtrack to my life. I was at my lowest ebb. Here was music with sorrow, defiance, triumph. And passion. It lifted me up; it inspired me. I would come through all this, and ultimately I would triumph. This was the kind of emotional journey that other people continue to recount, more than forty years later, when they talk to me about Beethoven.

Who was this man who had created something that could have such an effect? I knew only one fact about Beethoven the man, the single fact that anyone who knows anything about classical music knows. He is the one who went deaf. But if a composer loses his hearing, how can he compose? Even more incomprehensible, if Beethoven went deaf, how could he write music of such intensity and emotion – and passion – that it could transform lives?

In the summer of 1983 I took Bonnie to a Beethoven concert in the Kennedy Center in Washington, where I was based as ITN’s US correspondent. I forget who the performers were; I remember only that the conductor and solo pianist were father and daughter. The Egmont Overture opened the concert, followed by Piano Concerto No. 3 and, after the interval, Symphony No. 7. That swirling final movement, faster and faster, a headlong charge to the end, brought the audience to its feet amid shouts of ‘Bravo!’ We left the concert hall flushed and breathless.

A short taxi ride to Georgetown for a late supper, and we passed a bookshop, open even at this late hour. Browsing in the music section, I saw a thick paperback book, blue spine, the cover entirely taken up by a photograph of a monumental statue of a seated Beethoven. It was Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, edited by Elliot Forbes. Rather sheepishly, I said I’d like to read it. ‘Why don’t you?’ Bonnie encouraged me. I bought it.

My worries of a daunting read were soon confirmed: it was over a thousand pages long. The first forty pages were about the prince-elector’s court at Bonn. Not a single mention of Beethoven. I struggled through two or three hundred pages, then gave up. Inside the back cover I made a few pencil notes. That paperback book is sitting in front of me now. The spine has long since collapsed. The whole thing is held together by brown parcel tape. The pencil notes have faded to illegibility. I have devoured every page more times than I can say.

In 1992 my mum died after a long illness. It was a deeply painful time. Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony helped me through that, as it had done with my personal crisis a decade earlier. By now I had quite a collection of Beethoven cassette tapes. Music had been an essential part of my life since my teenage years, but this passion for Beethoven’s music, which had begun slowly, had overwhelmed me. It was no craze. I knew, deep down, not only that it would never go away, but that it would intensify.

I had been casually reading up on Beethoven’s life throughout the 1980s. Now I needed to know more. That is how I came to be in Bonn, visiting the house where Beethoven was born, in 1993. A year later I started writing my own account of his life. Thirty years on from that, and eight books later, I am still writing about his life and music.

3

The story begins with a young man in search of love, though exactly what led Johann van Beethoven to conduct that search some fifty-five miles or so upriver from his home town of Bonn in the small commune of Ehrenbreitstein on the opposite bank of the Rhine, we do not know. Most likely he had sung with his choir there, and spotted a charming girl whose name, he discovered, was Maria Magdalena.

An added motive for seeking a bride away from Bonn was undoubtedly to escape from the overbearing influence of his father, Ludwig van Beethoven. It is not easy for a son who follows in his father’s profession to realise that he will never come up to his father’s exacting standards. It is all the more difficult when the father also realises this and frequently berates the son for his mediocrity.

‘There are in reality three Johanns standing together like in a clover leaf,’ a neighbour heard Ludwig van Beethoven say in front of his son. ‘The apprentice lad is Johann the muncher, always gobbling away; the lad in the house is Johann the chatterbox, and then there is this third Johann,’ – and these are cruel words for a father to use to his son – ‘Johann the runner. Keep running, keep running, one day you might even reach your destination.’1

Lodewijk van Beethoven (who would become grandfather to the composer), also called himself by the classier French equivalent of ‘Louis’, had reason to be proud of his achievements. Born in Mechelen2 in the Netherlands, around twenty miles north of Brussels, he saw his own father work as a baker day and night but still fail to stave off bankruptcy. He himself was blessed with a fine voice, and found employment as a bass singer at the Cathedral in Liège. There, as a young man, he was heard by the Prince-Elector of Cologne, who offered him employment as a court musician in Bonn.

Lodewijk left Mechelen and moved to Bonn on the banks of the Rhine, where the prince-elector had his palace. There he soon married a young woman by the name of Maria Josepha Poll, adopted the German form of his own name, and as Ludwig van Beethoven forged a successful career as court musician.

So successful in fact, showing organisational skills as well as musical prowess, that in 1761, aged forty-nine, he was appointed to the highest musical position at court, Kapellmeister, in charge of all musical activity – most unusual for a musician who was neither composer nor instrumentalist.

Of the three children born to the Beethovens, only one survived into adulthood, a son who was christened Johann. In time Johann developed a fine tenor voice, and his father secured him a position at court as a member of the prince-elector’s choir. Johann also gave singing and piano lessons on the side, which supplemented his income.

Kapellmeister Ludwig van Beethoven had a rather different secondary source of income. He dabbled in the wine trade. In fact he did more than dabble; he was a rather prosperous wine merchant. He rented two wine cellars, and through his friendship with the court cellar clerk, Johann Baum, learned where the best wine-producing vines grew, and the techniques of grape-pressing and fermentation. The wine he produced he shipped back to the Netherlands, where it was highly rated by connoisseurs. He also sold locally to Bonn residents.

A comfortable family set-up, then, with father and son in well-paid jobs, both earning extra income on the side. It was common gossip in musical circles that the son would be front runner to succeed the father as Kapellmeister in the fullness of time. But ominous clouds were gathering over the heads of the Beethoven family.

The culprit was the demon drink. Inevitably, as the wine business prospered, there was plenty of wine on the Beethoven table too. This was to have a devastating effect on the family. Maria Josepha, wife of the Kapellmeister, became an alcoholic. Husband and son were either unable, or unwilling, to look after her at home. She was put into an institution in Cologne, where she remained for the rest of her life. Of more importance to our story, their son Johann would increasingly turn to drink, which ultimately ruined his career, blighted his family and led to his death just one month after his fifty-second birthday.

History, and Beethoven scholarship, have broadly been kind to Ludwig van Beethoven, Kapellmeister. Neighbours and friends remembered him as good-hearted and respectable. But they also described how his vitality and strength could easily transmute into stubbornness, forcefulness, even violent temper – qualities that later manifested themselves in abundance in his famous grandson.

Maria Magdalena, in the Kapellmeister’s eyes, was thoroughly unsuited to be his son’s bride. At the age of nineteen she was already a widow and the mother of a child who had died in infancy. A mother and a widow – hardly an exemplar of bridal purity. Added to this she was an outsider from a small town somewhere south of Bonn. For a man who undoubtedly had a degree of snobbishness about him, Maria Magdalena was simply not of a high enough class to marry into the Beethoven family. His own inquiries established that she had once been a chambermaid. ‘This I would never have believed of you, that you would have sunk so low,’ he remonstrated with his son.3

In fact the Kapellmeister’s informant was mistaken. Maria Magdalena had never been a chambermaid. Her maiden name was Keverich, and she belonged to an important and well-respected family in Ehrenbreitstein. Her father oversaw the kitchens at the prince-elector’s court, and her mother’s family included several high-ranking local officials.

Nevertheless, the Kapellmeister had made up his mind. He wanted nothing to do with his son’s marriage. The antagonism of the Kapellmeister to the Keverich family was reciprocated. No Keverich relatives made the short journey to Bonn to attend the wedding. Thus, when on 12 November 1767 Johann van Beethoven married Maria Magdalena Leym née Keverich in St Remigius parish church in Bonn, neither family was represented.

The ceremony was hurriedly arranged and kept as short as possible. In later life Maria Magdalena would say she could have had a good wedding were it not for her father-in-law’s opposition to the match and refusal to attend the ceremony. For that reason too, the wedding was never mentioned in the Kapellmeister’s presence.

The day after the wedding the newly married couple travelled by coach south along the Rhine to Koblenz, and across the river to Ehrenbreitstein to show the bride’s family and friends she was married and to introduce her husband to them. The couple remained there for three days before returning to Bonn for further celebrations.

Seventeen months later Maria Magdalena gave birth to a son, Ludwig Maria, who lived for less than a week. One year and eight months after that, on 16 December 1770, she gave birth to her second son. It was a bitterly cold December day, and for that reason the baby was born in the kitchen of the small house in which the Beethovens rented first-floor rooms.

The infant was baptised the next day in the Remigiuskirche, the same church of St Remigius where his parents had married, and was given the Latin form of his grandfather’s name, Ludovicus.

4

The church of St Remigius stands tall today on the Brüdergasse in the heart of old Bonn. To walk in Beethoven’s footsteps and those of his family, it is imperative, I felt, to walk up the aisle of the church where his parents married, where he was baptised and where he would play organ at Sunday morning Mass at the age of just twelve.

‘It’s simple,’ I said to Nula, map unfolded. ‘Here is Remigiusplatz. It’ll be on the square, obviously.’ Heroically we set off for Remigiusplatz, a small, tightly packed square of shops and cafés. But where was the church? On our third circuit of the square, having checked it wasn’t hidden behind one of the façades, Nula suggested that maybe there was no church here at all.

‘But look!’ she said. ‘There’s a spire. That must be it.’

There was indeed the welcome sight of a spire rising above buildings some distance away.

‘Too far,’ I said. ‘Why would St Remigius Church be so far from St Remigius Square?’

‘Because names change over the centuries,’ Nula replied reasonably.

We walked and walked. Tired by now and somewhat frustrated, we were relieved to find ourselves at the entrance of a large Gothic church that proclaimed itself to be St Remigiuskirche. The interior was vast, with a high vaulted ceiling. It seemed rather more modern and in better repair than I had expected. No service was being held, and there was just one other person inside, an elderly man sitting alone in the back pew.

My enthusiasm got the better of me. ‘It’s amazingly grand, isn’t it? I wasn’t expecting anything so huge. Incredible to think Ludwig’s parents, and then Ludwig himself – try to imagine him as a small boy at the organ, he must have been dwarfed by . . .’

To my horror the elderly man turned, his face grim. His eyes locked with mine. He raised himself slowly from the pew, held onto the side for a moment to steady himself, then began – purposefully – to walk towards us. Already in my head I was framing my apologies in German for disturbing him.

As he reached us, his stern expression melted and a smile lit up his face. He spoke in heavily accented Rhineland German. ‘Grüss Gott! Have you come here because of Beethoven?’

I nodded vigorously.

‘Hah! Then you know you have come to the wrong church.’

I played back his words in my head. Had I misunderstood? Had I heard a falsch when there was none? He repeated it, shaking his head.

‘Where are you from?’ he asked, smiling.

Swiftly I explained, willing him to get back to the subject. ‘I am English. My wife is Irish. I am researching for a new book I am writing on Beethoven.’

‘Then let me explain,’ he continued. ‘Come with me.’ He took us to the side wall of the church, where there were screens containing old black-andwhite photographs of a bomb-damaged church.

‘This is the church we are standing in. It was hit by bombing in 1944. Look at this church now. They have renovated it beautifully, don’t you think?’

‘Yes, they have,’ I said, mentally wondering if there was anything left of the original, ‘and to think, before the dreadful bombing, this is where Beethoven was baptised, and his parents . . .’

‘Ah no,’ he said. ‘As I told you, this is not where baby Ludwig was baptised.’

It took a moment for this to sink in. It was the second time he had said it, and this time there was a definite nicht.

He saw my confusion and smiled. He was rather enjoying himself. ‘You see, in 1800, I think it was, the original church of St Remigius – in Remigiusplatz – where Beethoven was baptised, was hit by bolts of lightning in a storm. It caught fire and was destroyed. They decided not to rebuild it. Instead they gave the name of the church, St Remigius, to this newer church, in memory of the old one.’

This meant that the church we had been looking for in Remigius Square, which had witnessed a Beethoven wedding and a baptism, no longer existed. It had not existed since around 1800. The church we were now standing in therefore had nothing to do with the Beethoven family. It bore the name alone of the original church.

A wave of disappointment washed over me. It was all a waste of time. Well, maybe not entirely. If we had not met him, I would confidently have asserted that Nula and I had walked in the footsteps of the Beethoven family in the church of St Remigius. So I had learned something important, even if it was entirely negative.

But our old man was not finished. He sensed my disappointment and a smile crept over his face as he prepared to deliver his punchline, raising his hands for effect and building in a slight pause, like the finest raconteur. I braced myself, concentrating on every word delivered in that quick-fire Rhineland accent.

‘The font that Beethoven was baptised in, the actual font, is over there in the corner.’ He turned and pointed behind him.

Taufbecken – I had never heard the word. It had to mean ‘font’, surely? Or had I misheard him? Well, there was a simple way to find out.

Our friend was pointing vigorously to the far corner of the church. Nula and I walked across. As we came closer, I felt my chest constrict and my heart quicken. There, on a slightly raised floor, a small stained-glass window gazing down, a tall candle to the side, was an ornate heavy-lidded font. The lid was attached to a pulley so that it could be raised.

‘That’s what fonts were like in the old Catholic Church,’ Nula said. A sign to the side stated that this was indeed the font in which the baby Ludovicus was baptised on 17 December 1770 in the church of St Remigius. When the old church burned down, they had had the presence of mind to save the historic font.

I gazed in wonder. We had failed to find the old church because it had not existed for more than two centuries. We were now in the wrong church, but looking at the font around which had stood Beethoven’s parents, his grandfather the Kapellmeister who was godfather, and a next-door neighbour, Gertrud Baum, who was godmother. And which, prior to this day, I had not known existed.

It was all thanks to our old man who, he told us, was eighty-seven years old. He had lost his wife twenty-five years before and liked to come and sit in this church and reflect. Nula hugged him like an uncle and he held her close. He extended his hand to me for the warmest of handshakes. We looked at each other with tears in our eyes.

5

The town of Bonn was built on slightly raised ground a safe distance from the Rhine, which was prone to burst its banks in winter. Several streets led down to the river, their residents collectively celebrating each spring if they had survived the winter unflooded.

Johann van Beethoven rented rooms on the first floor at the back of a tall house at Bonngasse 515, owned by a lacemaker named Clasen. It was situated in the centre of town a short – but safe – distance from the river. After his wife was sent to Cologne to be looked after, the Kapellmeister lived alone, directly across the narrow street. The windows of the rooms housing the Beethoven family looked out over a small dark courtyard.

The house still stands today, with a different number – Bonngasse 20. That is not all that has changed. The house remained in private hands for most of the nineteenth century, the ground floor opening as an inn in 1873, with the name ‘Beethoven’s Geburtshaus’ (Beethoven’s birthplace). A decade and a half later a beer hall where music was played was built in the courtyard at the back. A merchant took over the house in 1888 but put it up for sale the following year.

Although it was clearly well known as Beethoven’s birthplace, the city of Bonn was not interested in buying the house. So the Verein Beethoven-Haus (Beethoven-House Society) was founded, with the aim of purchasing the house and turning it into a permanent memorial to Bonn’s most famous son. Once the house was acquired, extensive renovations were carried out, inside as well as out. Rooms were enlarged to accommodate display cases and memorabilia, as well as a library. Space was allocated for the society’s office, as well as an apartment for the caretaker. A second staircase was added to the rear of the building. The beer hall was demolished, the courtyard was paved and a small garden created. Today a bust of Beethoven on a plinth stands at the back of the garden, his stern gaze directed downwards to the ground.

Beethoven’s birthplace was officially opened on 10 May 1893, but that is far from the end of the story. In 1907 the house next door, where his godmother Gertrud Baum and later his boyhood friend Franz Wegeler had lived, was acquired to house the Beethoven-Archiv, which is today the most important research centre into Beethoven’s life and music in the world. Among original letters and autograph manuscripts, it contains the ultimate treasure of treasures: a life mask of Beethoven made by Franz Klein in 1812.

Minor damage suffered during two world wars was repaired at the beginning of the 1950s. Twenty years later there was more extensive restoration work, and again in the 1990s.

It is easy to say that today the house bears little resemblance to the one in which Beethoven was born, that it is impossible to imagine the warm, steamy kitchen where Maria Magdalena, flushed and breathless, gave birth to her third child on that cold December day. The house is one of the few in Bonn that date back to the eighteenth century, and stepping inside you get an unmistakable sense of a time long gone. Stand in the small garden where once a beer hall stood and look up at the first-floor windows – the rooms Johann rented – and you realise the smallness of their living quarters. If they were at the windows gazing down at you they would not see a pretty grassed garden but a dark, dank, narrow courtyard.

We should marvel that the house has survived in any form at all, after nearly a century in private hands and then two world wars. For each of my previous three visits – the earliest in 1993 – a room on the first floor has been designated as the room in which Ludwig van Beethoven was born. The third time a marble bust stood on a pedestal and the room was roped off. The fourth time, in October 2022, the day before our St Remigiuskirche encounter, the room had a large video installation that stretched across the window showing musical manuscripts. You could enter the room but not see out to the garden. This seemed strange for a room previously held in such esteem.

I mentioned this to one of the guides, who said, ‘We now believe Beethoven was born in the kitchen here on the ground floor. It was mid-December and in Bonn it is very cold in December. The kitchen was the warmest room.’

‘Where was the kitchen?’ I asked.

She pointed behind us and smiled. The room contained display cases and pictures. There was nothing to say it was the birth room, because after all the renovations and restoration it really is impossible to know.

I have been told by a Beethoven musicologist with close ties to the Beethoven-Haus that in fact it has never been possible to say in which room Beethoven was born, given the extensive renovation work. But over the years so many visitors asked to know in which room the great composer was born that the society decided to designate that first-floor room, which on an earlier visit I had found roped off.

When I first visited in 1993, the ‘gift shop’ in the birthplace was a table under the back staircase. On offer was a small collection of cassette tapes and some leaflets on various aspects of Beethoven’s life. On my next visit, just a few years later, a dedicated shop had been opened in the building next door. It was not large, but there was a good selection of books and CDs. One of the CDs was of my favourite piano sonata, the middle of the final set of three, No. 31 in A flat, Op. 110. The saleswoman told me it was recorded in 1967 on the Graf piano that was in Beethoven’s Vienna apartment when he died, and that now stands in the birth house, its keyboard protected by a perspex cover. ‘That was the last time Beethoven’s voice was heard,’ she said.

Now there is a huge souvenir shop directly across the Bonngasse from the birth house, with a vast array of books, CDs, DVDs, pens, paperweights, umbrellas, socks, and much else. When Nula and I visited in July 2022 I was delighted to see the special 250th anniversary edition of my book Beethoven – The Man Revealed on the shelf. Nula took a picture of me pointing at it and grinning like a Cheshire Cat. When I came to buy two entry tickets to the birth house opposite, the saleswoman refused to take my money.

The birth house itself is one of the most visited sites in Germany, which is not the case for a much more important location, just a short distance down the gently sloping hill towards the Rhine.

The Beethoven brood was growing. Ludwig had survived infancy and Maria Magdalena had since given birth to another son. It was clear the family needed larger accommodation. But before we accompany them to the house where Ludwig was to spend the formative years of his youth, I have to recount an event that shook the Beethoven family to its roots – an event that Ludwig would carry with him for the rest of his life.

6

On Christmas Eve 1773 Kapellmeister Beethoven, having suffered a stroke earlier in the year, died at the age of sixty-one. To an extent his family had time to prepare, but it still came as an enormous shock. Johann van Beethoven suddenly found himself head of the family, with all the responsibilities that brought. But with those new responsibilities came one or two unwelcome discoveries.

His father, it appears, had not been quite as efficient at running his wine business as he had been at organising his own and others’ musical lives. When Johann examined the books, he discovered wine producers to whom his father had loaned money and who had not repaid it, and others who had been paid in advance for their wine but had not delivered it.

When Johann confronted the vintners, they demanded written proof. Johann was forced to concede that his father was such an honest man that he had relied on promises and handshakes alone. He also knew that vintners had often paid his father in kind – a good fresh slab of butter and a fine mature cheese, for instance, instead of cash. What Johann had most certainly not expected to inherit from his father was considerable debt.

But his demise also meant there was one propitious development in the offing, and it mitigated Johann’s grief considerably. He was the natural successor to his father in the highest musical post in Bonn – Kapellmeister – an appointment that would bring with it not just prestige but a greatly enhanced salary. He considered it his birthright. In order to be seen to be doing the right thing, Johann wrote a letter to the prince-elector putting himself forward for the post, using the most florid language to state that he was not just the best but the sole musician at court worthy of such a prestigious appointment.

Unfortunately, he was the only one who thought so. Johann’s unsavoury habits had not gone unnoticed. It was difficult to sing adequately or perform properly as a music teacher after a heavy drinking session the night before. He would have to continue to feed a growing family on a relatively meagre salary, supplemented by fees for teaching, with no prospects of advancement. Maria Magdalena was five months pregnant when her father-in-law died. Her second son was born on 8 April 1774 and christened Caspar Carl.

Just as history has been unstintingly kind to Ludwig van Beethoven the Kapellmeister, with universal praise for his musical prowess and blameless life, so it has been equally harsh in its condemnation of his son Johann for his dissolute and profligate ways. In the case of both individuals the truth is more subtle. Besides his carelessness with money, the Kapellmeister, as we have seen, had an arrogance about him, dominating and constantly criticising his son.

As for Johann, he might have been profligate but he was certainly not mean. Nor was Maria Magdalena inclined to censor her husband’s drinking habits. Gottfried Fischer, who grew up in the same house as Ludwig, described how at the end of the month, when Johann van Beethoven brought home his earnings, he would shake the money into his wife’s lap and say, ‘Now, wife, keep house with that.’

She would give him some back so he could buy a bottle of wine, saying, ‘You can’t let men go away empty-handed. Who’d have the heart to do that?’

‘Quite right,’ he would respond, ‘so empty-handed.’

She’d then say, ‘Yes, so empty-handed, but I know you’d rather have a full glass than an empty one.’

Johann would end the exchange with ‘The wife is right, she is always right, and what’s more she will always be right.’1

The marriage was not always so harmonious, as we shall see later. For the moment, though, we rejoin the Beethoven family in their small apartment in the Bonngasse, the infant Carl and his devastated elder brother. Yes, devastated. For no one in the family was hit harder by the Kapellmeister’s death than Ludwig.

We have, obviously, little information from Beethoven himself about his grandfather, since he was just three years and eight days old when the old man died. We do know, though, that Beethoven grew up with a portrait of the Kapellmeister showing him dressed in the finery of his office – a fur hat and purple cape over a tassled, fur-trimmed jacket – and holding a manuscript and pen. His father would later pawn the painting, but when Beethoven moved as an adult to Vienna, he wrote to an old friend back in Bonn, asking him to retrieve the portrait from the pawnbroker and forward it to him. It then hung on the wall of every apartment that Beethoven lived in, including the one in which he died.

We know from the same friend2 that the young Beethoven ‘retained the most vivid early impression of him’ and would often talk about his grandfather with his childhood friends.3

In 1776, when Ludwig was five and his brother Carl two, the family moved into a rather fine house just a stone’s throw from the Bonngasse in the Rheingasse, which, as its name implies, leads down to the mighty river – then, as it still does today.

Johann rented a spacious second-floor apartment consisting of no fewer than six rooms. Two large rooms faced the street, with a connecting door that could be opened to create a space for musical recitals. Four rooms faced the courtyard behind. With interruptions, the Beethoven family would live here for nine years.

The house was owned by master baker Fischer, and it was his son Gottfried who, with the help of his elder sister Cäcilie, would later write his memoir of growing up in the same house as the great composer.

There was a piano in one of the front rooms. Here Johann gave keyboard and singing lessons. And it was here that the boy Ludwig first began to play music – not just the piano but the violin too.

That was not all he did to amuse himself, and his other pleasures had nothing to do with music.

7

There is no river in Europe, or in the world, so steeped in legend as the Rhine. The Loreley, the rock to which a siren maiden lures sailors to their death; the Mäuseturm (Mouse Tower) in the middle of the river, in which a hapless bishop took sanctuary from rampaging mice, only to be devoured by them; treasures thrown into the river and hidden below the river bed.

And, most important for our story, the Drachenfels (Dragon Rock), which stands on the opposite bank about eight miles upriver from Bonn. The Drachenfels is the largest of the Siebengebirge (Seven Mountains) that stretch away from the opposite bank, and which every Bonner knows were created by giants digging out lakes and throwing shovelfuls of earth over their shoulders.

Every Bonner would also know the legend of the Drachenfels, one of the most powerful of all Rhine legends, and how the dragon who lived in a cave halfway up the rock was denied his annual feast of a virgin by the timely arrival of the Teutonic hero Siegfried, who slew the beast with his invincible sword.1

Every Bonner includes the youthful Ludwig van Beethoven. Gottfried Fischer tells us in his memoir that the Beethoven family loved the Rhine. He also tells us that in the attic of their house were two telescopes, one large and one small. The Fischer house was one of the tallest in Bonn and so afforded a beautiful view across and up the Rhine. Ludwig, if no one could find him, was certain to be in the attic, gazing up the Rhine through one of the telescopes.

The ruined castle that stands jagged on the peak of the Drachenfels had already been part of the Rhine landscape for several hundred years by the time Ludwig brought it into focus through the telescope. The sight of it from Bonn, reaching up like a broken hand from the summit of the Drachenfels, is today just as it was when Ludwig gazed at it, though he would no doubt marvel at the sight of the rack-and-pinion railway that since 1883 has taken visitors from Königswinter, the small town that lies at the foot of the Drachenfels, to the viewing platform high up on the rock.

The dragon, said superstitious tongues, exacted its revenge when, in 1958, the train derailed and seventeen people lost their lives. I knew nothing of that tragedy when I eschewed the train and climbed the rock by foot back in 1993 in the early days of my Beethoven research. Surely Ludwig, as a boy, must have made the climb. We know he spent days away from home, walking and climbing in the Siebengebirge, content in his own company – as he would walk in nature all his life. For my part, I remember having lunch in a wood-panelled restaurant in Königswinter, and making the climb well fortified by a half-litre of local white wine.

We can imagine Ludwig playing out the legend of the Drachenfels in his head, as he stared at it through the telescope. On one occasion Cäcilie Fischer recounted how she asked him, ‘What are you looking at, Ludwig?’ He gave no answer. Later she asked him why he had not answered her, pointing out that was rather impolite.

‘No answer is an answer too,’ Ludwig replied. ‘I was just occupied with such a lovely deep thought, that I could not bear to be disturbed.’2

Ludwig might have wished for more time with the telescopes, but for his father there was another path to pursue. How Johann first noticed his son’s musical talent we do not know. Most likely Ludwig doodled on the piano keys in ever more impressive ways. The keyboard was too high for him so he would stand on a low bench to play. Johann began to teach him to read music. Soon the child was playing pieces of considerable technical difficulty in a way that astounded the father.

It was time for Johann to start making money from his son’s prowess – just as Leopold Mozart had capitalised on the extraordinary talent of young Wolfgang Amadeus. He arranged a recital at a concert room in Cologne. He announced one of his singing pupils would perform, accompanied at the piano by his young son, aged six, who would then play solo pieces.

Ludwig was seven on 26 March 1778, not six, and this discrepancy has led to much speculation. Why would Johann reduce his son’s age by a year? Simple answer: to exaggerate his extraordinary talent, and thereby encourage more comparisons with Mozart. This is backed up by the fact that Ludwig’s birth certificate has not survived. Why? Because Johann destroyed it, so he could continue to falsify Ludwig’s age without fear of contradiction. The continued fiction had a lasting effect. Until middle age Beethoven believed himself to be at least one year younger than he was, possibly two years younger.

The choice of Cologne for his son’s debut was a strange one. It was away from Bonn, true, so if it all went wrong it would stay safely away from musical colleagues at court, at least for a time. On the other hand, Cologne was a large important city with a thriving cultural scene. It would be a more difficult nut to crack than small provincial Bonn.

There are no contemporary accounts of the recital, but it must have gone well, because Johann decided his son’s musical talent needed more careful nurturing. By coincidence a room in their apartment that the Beethovens were subletting was occupied by a musician – a pianist, oboist, flautist and actor by the name of Tobias Friedrich Pfeiffer, who was in Bonn as a member of a theatrical touring company.

Johann van Beethoven hired Pfeiffer to give his son music lessons. It was both a good and a not so good decision. To take the not so good first. Pfeiffer was a drinker. When he fell ill, the maid of the house reported that late at night, after the others had gone to bed, he would order her to bring him wine, beer and brandy, which he would then drink one after the other.

Johann van Beethoven soon found in Pfeiffer a convivial drinking companion, with whom he would stay out till midnight drinking. And thereby has arisen an imperishable legend.

Watch any film or documentary on the life of Beethoven, and you will see the drunken father pulling the sleeping boy from his bed in the middle of the night, dragging him to the piano and forcing him to play, rapping his knuckles as tears fall down his cheeks.

This did not happen. The legend is based on a single sentence in a memoir by an obscure court cellist by the name of Bernhard Joseph Mäurer, in