5,12 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

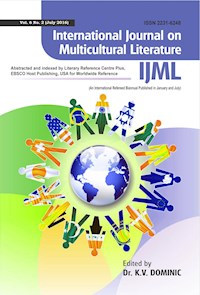

International Journal on Multicultural Literature (IJML) Volume 6 Number 2 (July 2016)

ISSN 2231-6248

Highlights include: "Portrayal of Man-Woman Pairs in the Fictional World of D. H. Lawrence: An Analysis" --S. Chelliah "Feminism and Feminist Literary Theory: A Brief Note" --C. Ramya "Portrayal of Feminine Spaces and Sensibilities in the Short-fiction of Alice Munro" --Syed Mir Hassim & M. Revathi "Violence, Memory and Identity in Indian English Fiction" --Barinder Kumar Sharma "Relevance of Neo-Slave Narrative Technique in Toni Morrison's Beloved" --Jaya Singh "'Mangalamkali' of Mavilan Tribe: An Ecocritical Reading" --Lillykutty Abraham & Sr. Marykutty Alex

IJML is a peer-reviewed research journal in English literature published from Thodupuzha, Kerala, India. The publisher and editor is Prof. Dr. K. V. Dominic, renowned English language poet, critic, short story writer and editor who has to his credit 27 books. He is also the secretary of Guild of Indian English Writers, Editors and Critics (GIEWEC). Since 2010, IJML is a biannual journal published in January and July. The articles are sent first to the referees by the editor and only if they accept, the papers will be published. Although based in India, each issue includes worldwide contributors.

Although IJML concentrates on multiculturalism, it also encompasses other literature. Each issue also includes poems, short stories, review articles, book reviews, interviews, general essays etc. under separate sections. IJML is available in paperback, Kindle, ePub, and PDF editions.

Distributed by Modern History Press

LCO004020 LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Asian / Indic

LIT008020 Literary Criticism : Asian - Indic

POL035010 Political Science : Political Freedom & Security - Human Rights

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

International Journal on Multicultural Literature (IJML)

(A Refereed Biannual published in January and July)

Volume 6 Number 2 (July 2016) ISSN: 2231 –6248

Abstracted and indexed by Literary Reference Centre Plus, EBSCO Host Publishing, USA for Worldwide Reference

Edited by

Dr. K. V. DOMINIC

Published ByDr. K. V. Dominic, XXI/439, Thodupuzha East, Kerala, India – 685 585. Email: [email protected]. Phone: +91-9947949159. Web Site: www.profkvdominic.comBlog: www.profkvdominic.blogspot.in

CONTENTS

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Portrayal of Man-Woman Pairs in the Fictional World of D. H. Lawrence: An Analysis

- S. Chelliah

Feminism and Feminist Literary Theory: A Brief Note

- C. Ramya

Portrayal of Feminine Spaces and Sensibilities in the Short-fiction of Alice Munro

- Syed Mir Hassim & M. Revathi

Violence, Memory and Identity in Indian English Fiction

- Barinder Kumar Sharma

Relevance of Neo-Slave Narrative Technique in Toni Morrison’s Beloved

- Jaya Singh

‘Mangalamkali’ of Mavilan Tribe: An Ecocritical Reading

- Lillykutty Abraham & Sr. Marykutty Alex

What do Stories Look Like: Cover Matters in Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide

- Pothapragada Sasi Ratnaker

Beyond the Contours of Shame: Female Body and Experience in Nawal El-Saadawi’s “The Picture”

- Shaista Taskeen & Syed Wahaj Mohsin

“Quidditch”- A Game of Life: An In-depth Insight into J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and The Philosopher’s Stone

- C. Veeralakshmi & C. Gangalakshmi

Individual vs. Society: A Thematic Study of K. V. Ragupathi’s The Invalid

- S. Vishnupriya

REVIEW ARTICLE

A Critical Appraisal of S. Kumaran’s, (ed.) Philosophical Musings for a Meaningful Life: An Analysis of K. V. Dominic’s Poems

- Patricia Prime

BOOK REVIEWS

Smita Das’s (ed.) Ramesh K. Shrivastava: Man and His Works

- Anisha Ghosh Pal

Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya’s Interpretation of Write My Son, Write: An Exercise in Close Reading

- Mahboobeh Khaleghi

T. V. Reddy’s Golden Veil: A Collection of Poems

- Patricia Prime

GENERAL ESSAYS

Multiculturalism in India: A Wonder to the World

- K. V. Dominic

Parnassus As I see it

- Manas Bakshi

Poets as Visionaries

- Rob Harle

Sab Pass Policy

- Kaptan Singh

EXPLICATION OF POETRY

Explication of K. V. Dominic’s “Parental Duty”

- Ramesh Chandra Mukhopadhyaya

SHORT STORIES

Together We Live

- Ramesh K. Srivastava

Just a Human Being

- Roswitha Joshi

POETRY

The Digging

- Bimal Guha (Trans. Prof. Kabir Chowdhury)

Ravens

- Bimal Guha (Trans. Prof. Kabir Chowdhury)

We stay hugging this earth

- Bimal Guha (Trans. Prof. Kabir Chowdhury)

The Eternal Truth

- Manas Bakshi

Parnassus of Revival

- Manas Bakshi

World Cup Opening

- Mark Pirie

Prince Harry’s Visit

- Mark Pirie

Hand-in-Hand

- Nandini Sahu

Ritual

- Nandini Sahu

Lines to My Son

- Nandini Sahu

Night Musings

- Patricia Prime

This Place Called Home

- Patricia Prime

In Memory (For Glenys)

- Patricia Prime

Storm Wrack

- Patricia Prime

The Opening Ground

- Mai Vãn Phãn (Trans. Nhat-Lang Le)

The Soul Flew Away...

- Mai Vãn Phãn (Trans. Nhat-Lang Le)

Variations on a Rainy Night

- Mai Vãn Phãn (Trans. Nhat-Lang Le)

Eco-feminism

- Saji Krishna Pillai

Transcend…end…end…endal Love

- Saji Krishna Pillai

To my coy mistress

- Saji Krishna Pillai

Life

- Saroj Bala

Beginning

- Saroj Bala

No One Questions

- Shaista Taskeen

Fifty Minutes from New Delhi

- Sweta Srivastava Vikram

Contributors

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Portrayal of Man-Woman Pairs in the Fictional World of D. H. Lawrence: An Analysis

S. Chelliah

Abstract: This paper attempts to project D. H. Lawrence as a difficult writer gifted with the remarkable writing skill to fashion almost all characters portrayed in his novels after his own personality by showing to the world that anyone who writes on D. H. Lawrence today is out and out confronted with two formidable difficulties: the complexity of his writings and the size of critical and biographical literature which has accumulated around him. It clearly colours his conception of life and human relationship with a focus on his own statement as “Art should arise from life”. It studies in depth the changing rainbow of our living relationships through the relationships of two pairs, Gerald-Gudrum and Birkin-Ursula, making a drama of disintegration move to a frozen finality. This brief analysis testifies to the fact rather clearly that the future of mankind depends upon a man-woman relationship where there is full and free scope for the creative flowering of sex unhampered by the barriers of class and conventions.

Keywords: Psychoanalysis, Moral, Relationship, Conflict, Freedom

Anyone who writes on D.H. Lawrence today is out and confronted with two formidable difficulties: the complexity of his writings and the size of critical and biographical literature, which has accumulated around him. Almost everyone who knew Lawrence wrote a book about him and tried to highlight that part of him, which he or she knew. Lawrence became “a Johnson surrounded by a shoal of Boswells.” It is generally held that in the beginning of the twentieth century, emphasis in English fiction got shifted from the external to the internal, from the impersonal to the personal, from circumlocution to psychoanalysis. Consequently, the very structure of the novel gradually changed from that of a ladder to that of a cobweb. And the novel got entangled in the self rather than the social world. This change gave a fresh fillip to the writing of autobiographical fiction, although ever since the beginning of the novel as a literary genre, the personal element has been present in some form or the other. But the average fictionist dislikes being called “a parrot of fact” (Wallace 19) and prefers instead the distinction of being an original, imaginative creator who creates every character, theme and episode in tune with the personal experiences of a fictionist.

D. H. Lawrence’s personality was, as it were, a crystal of many facts. He fashioned many characters in his novels after his own personality. At times, he capitalized even one single facet, and very frequently more than one, bearing sufficient potentiality to create one remarkable full-size character. It is not possible for a literary artist to wave aside his personality and then write. Lawrence admits it in his essay, “Pornography and Obscenity” as: “The author never escapes from himself, he pads along within the vicious circle of himself. There is hardly a writer living who gets out of the vicious circle of himself or a painter either” (180). The novel could be “anything and everything.” Like the art-form the essay, it elides all attempts to circumscribe it within fairly precise limits. The novel has thus served as a medium for an astonishing variety of things from pontifical moral preaching to pulse-racing pornography. The most noteworthy novelists in English fiction were D. H. Lawrence, Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf and James Joyce of them, Lawrence and Joyce have dominated the interwar years in striking contrast to each other as writers of unquestionable genius.

D. H. Lawrence is a difficult writer for those who are introduced to him for the first time. In order to come to grip with his works, particularly the novels, one needs a fair measure of acquaintance with his expository works and a knowledge of the special sense in which certain key words are used. The peculiar approach to life and problems that springs from his special genius has imposed a good deal of hardship on him as a novelist, at the same time posing a serious challenge to any reader tackling him for the first time. In the first place, it is not easy to fit Lawrence into any obvious scheme of the modern novel.

Though he was a revolutionary like Joyce in the conception of prose fiction, he was not concerned with the problems of time and consciousness. He made no technical innovations, but revealed himself startlingly original in the matter of characterization. He is less concerned with the situation in which his characters are placed. His men and women are different from the flesh and blood characters we come into contact with in the novels of Dickens or Hardy. They are “centres of radiations quivering with the interchange of impulses” (371). Lawrence looks upon them as diverse manifestations of the life-impulse and therefore, ‘plot’ is hardly found in his novels in the usual sense of the term. There are neither moral issues to be finalized nor conflicts to be settled. As individuals are vehicles of energy, great importance is attached to the feelings of the people at the point of contact. The individuals are mutually attracted by mysterious forces and not by social graces. Love or the erotic impulse appears like an electric charge. The individuals are brought into violent contact with one another, thanks to certain chemical affinities. Lawrence has stated that “the goal of life is the coming to perfection of each single individual” (qtd. in Karl 154). A sincere student of Lawrence finds that he extends our universe. One encounters ideas and mental states that are “novel experiences until one comes to grips with them on the artistic plane” (Hough 4). In one of his novels, Lawrence came out with a statement on the true role of fiction which throws light on the status of Lawrence as a novelist and he is said to have broken away from the novelistic conventions of his predecessors because he wanted the novel to project his conception of life and human relationships. Art, according to Lawrence, should arise from life, “The business of art is to reveal the relation between man and his circumambient universe at the living moment” (175). Lawrence looks upon novel as the perfect medium for projecting the changing rainbow of our living relationships, Gerald-Gudrun relationship is a bond of hate-love, sado-masochistic sexuality. He has drawn the nature of their pulls and counter-pulls with such deep identification that he invokes “the surcharged convulsions and tumescences” with an intensity that often exceeds the dramatic needs “with an intensity that often exceeds the dramatic needs” (Cavitch 55). The two pairs, Gerald-Gudrum and Birkin-Ursula intertwine throughout the novel Women in Love, but they stand for opposed values, one ‘life-giving’, the other being ‘death-dealing’. When Birkin and Ursula succeed in solving their problems partially and find a sort of salvation, Gerald and Gudrum are caught in a whirlpool of intense violence and corruption. Theirs is a drama of disintegration that moves to a frozen finality.

Gerald was a marked figure from the beginning, a man under a cross, with the shadow of doom and death hanging over him ever since his birth. As observed by Birkin, Gerald was, like a man offering his throat to be cult. “The process of dissolution began with the accidental killing of his brother as a child. It was an instinctual flaw that symbolized his denial of any life-tie among men” (Cavitch 68). Throughout his life, he moved in an atmosphere of death and decay. He was often associated with water, one of the principal symbols of death and dissolution in the novel. In the very first chapter, Gudrum instinctively recognizes that Gerlad is her destined lover. As soon as Gerald Crich arrived, “good-looking, healthy with a great reserved of energy”, Gudrun left the place as she wanted to be alone to know the “strange inoculation that had changed the whole temper of his blood” (24). Throughout the first half of the novel, Gudrun thrilled with excitement at every meeting with him and at the prospect of some conflict with him. Gerald’s attraction for Gudrun was at first quite casual. Later, it turned into a consuming passion. His declaration of love came as a pleasant surprise to Gudrun. She was a thrilling partner from that period to satisfy all his pent-up feelings of lust.

In the torrid love-affair of Gerald and Gudrun, Lawrence represents all his ideas of the negative side of man-woman relationship, opposed to the kind of one he draws in the sexual intimacy of Mellors and his sweetheart. There are many evidences in the novel Women in Love to confirm that it is a relationship marked by intense sexual attraction of the sado-masochistic type. The first hint is given in the “mare” incident. This was followed by the “rabbit” scene (xviii). Gudrun is excited by the brute and mechanical in him. Yet, she develops in her soul irrepressible urge to get even with him. It is this “unconquerable desire for deep violence against him” that forces her to strike him in the face after the frenzied dance before the highland cattle that has all the symbolic intensity of a male-female sexual confrontation surcharged with violence. The nature of the Gerald-Gudrun relationship is highlighted in the episode: “You have struck the first blow, ‘he said . . . .‘And I shall strike the last’, she retorted involuntarily, with confidant assurance. He was silent. He did not contradict her” (191).

David Cavitch’s observation that the circumstances of Gerald’s first sexual conquest of Gudrun illustrate that his lust for her started the process of his psychological disintegration is supported by internal evidence (qtd. in Cho XXIV). Commenting on this phase of Gerald’s relationship with Gudrun, Leavis notices the beginning of the see-saw battle between them that ends in his death. His ‘love’ is desperate need and utter dependence which becomes a deadly oppression to her. He, on his part, hates her because of his knowledge of his sense of utter dependence on her. In the remaining months of his life, he revels in a relentless pursuit of sexual orgy marked by infantile dependency and tortured orgasm symbolizing the way of self-destruction at the hands of Gudrun who victimized him by surrendering to his frenzies of abuse. Finally, the drama acts itself out in the high Tyrolese valley. After an almost fatal attack on Gudrun, overcome by revulsion and guilt for his meaningless life, Gerald at last has his end in an icy entombment. Julian Moynahan’s memorable words on the final end of Gerald-Gudrun affair deserve to be quoted: “The valley is a real place and simultaneously a symbol of fate for both Gerald Crich and civilized society . . . . Here where his vitality is at last to be bled white and empty of Gudrun’s hatred, the mathematically perfect forms of snow flakes, composing a chaos of white, mock him and his concepts of fulfillment” (70). The violence and cruelty of the closing scenes, as Graham Hough remarks, is Lawrence’s warning that the forces they have been graphing with are not to be treated lightly and that the penalties for failure can be death and destruction.

In contrast, one can examine a relationship growing towards life and continuity. This is preferred over the Ursula-Birkin affair, in spite of its superiority in the aesthetic sense and obvious inter-relationship for three reasons. In the first place, in Mellors-Connie affair, there is a closer parallel to the Frieda-Lawrence romance when taken into consideration the daring defiance of convention by the aristocratic lay who took all the initiative. Secondly, the love of the lady for the socially inferior man is free of the complexes, complexities, ambiguities and ambivalences of Birkin’s relationship with Ursula. The third factor that influenced us is that Mellors-Connie affair is Lawrence’s last attempt to say “everything about love, a summation of his fictional quest for sexual polarity” (198). There is a contrast worked out in the novel Lady Chatterley’s Lover itself, the contrast between the two realms where Lady Chatterley remains the vital link: the suffocating atmosphere of Wragby Hall and the unpolluted freshness of the woods nearby; the sterility and the life-giving, heart-warming quality of the forbidden relationship; the absorbing struggle between unvital and vital ways of apprehending experience. This is the primary theme of the novel, the dramatic concretization of the most important doctrine of the man-woman relationship of Mellors and Connie, Lawrence, by the implied contrast to Connie’s own household “dramatizes two apposed orientations towards life, the district modes of human awareness; the one abstract, cerebral and unvital; the other concrete, physical and organic” (Moynahan 72). The story of Connie Chatterley is the story of the modern woman who has not been awakened into phallic consciousness. As a girl, she accepted the current ideas about sex. After her marriage, she had a month’s honeymoon with her husband before he left for the war. When he returned from the war paralyzed and impotent, life stood still for Connie—the long years of unfulfilment in marriage stretching ahead of her. Oliver Mellors too had a tragic sexual experience before he became a game keeper for Connie’s husband. Embittered by his disastrous marriage to Bertha Coutts, Mellors deliberately chose the life of a social outcast. The first meeting of the would-be lovers did not produce and extraordinary reaction on either of them. As was the matter in the first encounter of Gudrun and Gerald, it was the woman only who was excited, through comparatively mildly in the case of Connie. The sudden appearance of the gamekeeper frightened Connie but she was no doubt, mildly interested. In later meetings, the gamekeeper appeared to her, however, quite reserved, reticent and even hostile.

The first shock of awareness came to the woman in Connie when she one day stumbled upon Mellors washing himself. On her return and pondered over the colossal waste of her golden youth and the deceit played upon her by the mental life. “Unjust! Unjust! The sense of deep physical injustice burned to her very soul” (LCL 64). A sense of rebellion smouldered in her. She began to make frequent trips to the wood in search of health and vitality. She was ready for the resurrection of the body, the re-birth through phallic consciousness. It was only the reluctance of the keeper, who recoiled from human contact because of his jealousy of privacy and freedom that delayed the meeting of the man and the moment. An incident took place touching the tender core of the man with the tough exterior. In that episode involving a “slim little chick”, Connie’s sterility is set against the life-symbol of a newly – hatched click” (Sagar 183).

Julian Moynahan finds a reversal in the climax of this scene. The gamekeeper who is “touched” experiences something that beckons him to the richness of life (90). Mellors’ skilful love making helps Connie to grow into a fulfilled woman. “As one lamp lights another, nor grows less”. Connie’s sensual awakening and physical rapture work wonders for the body and soul of Mellors. He too is filled with new life: “And now she touched him, and it was the sons of god with the daughters of man. How beautiful he felt, how pure in tissue.” Keith Sagar shrewdly observes the many marvellous changes the uninhibited sexual games produced in the woman in Lady Chatterley: “Her womanhood had hither to been erased by the social identity . . . . Mellors responds to her primarily as a woman and restores her to life at this level of her being. He connects her to the freshness and fertility of the woods. Her run-down body is recharged with life. She vibrates to herself with a sense of creativeness” (187).

The organic splendours detailed, twitching and jerking’s in the throes of sexual agony, the meanings and the thrashings, the masculine savagery and the helpless feminine surrendering, the casual spasms in the eruption of passion, the shuddering convulsions at the moment of fantastic sensations and the final devastating impact—the novel is explicit to the point of pedantry. The moments described have a close resemblance to the kind of sensations realized through Tantra, in their ego-shattering impact: “Tantra . . . seeks to use the rapture of sex to blast through the ego-protective barriers of our inhibitions and tap the incredible powers of this dark and omnipotent over mind” (Aravind 9). What Connie and Mellors was not tenderness but the dark sensuality Birkin had demanded (Pritchard 194) in the possession and acceptance of mankind’s ultimate physical reality. What is understood is that sexual relations are sweeter and deeper for Connie and Mellors than for any other pair of Lawrence’s Protagonists one can agree with David Cavitch that “They are the first major characters who are absolutely free of self-revulsion or any fear of sex and the novel focuses attention on their sensuality” (197).

From this brief analysis, it becomes clear that the future of mankind depends upon a man-woman relationship where there is full and free scope for the creative flowering of sex unhampered by the barriers of class and conventions: sex which is warm, sensual and mindless: the ultimate in phallic consciousness. The characters selected for this brief analysis are shown to be the men and women demonstrating the various aspects of the Lawrencian idea of the man-woman relationship and also the man-to-man attraction.

Works Cited

Beach, Joseph Warren. The Twentieth Century Novel: Studies in Technique. Ludhiana: Lyall Book Depot, 1969. Print.

Cavitch, David. D. H. Lawrence and the New world. London: Oxford University Press, 1969. Print.

Daiches, David. A Critical History of English Literature. London: Secker & Warburg: Ronald Press, 1960. Print.

Hough, Graham. The Dark Sun: A Study of D. H. Lawrence. London: Gerald Duck Worth & Co, 1956. Print.

Karl, Frederick R. and Marvin Megalaner.A Readers Guide to Twentieth Century English Novels. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973. Print.

Lawrence, D. H. “The Novel.” D.H. Lawrence: A Selection from Phoenix. Ed. A. A. H. Inglis. Harmonsworth: Penguin Books, 1971. Print.

McDonald, Edward D., ed. Phoenix: The Posthumous Papers of D. H. Lawrence. London: Heinemann, 1950. Print.

Moynahan, Julian. The Deed of life: The Novels and Tales of D.H. Lawrence. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966. Print.

Wallace, Irving. The Fabulous Originals. London: Four square, 1967. Print.

Feminism and Feminist Literary Theory: A Brief Note

C. Ramya

Abstract: The article traces the history of feminism from its beginnings as the intellectual arm of feminist movement. The feminist movement was rooted in the progressive movement and especially in the reform movement of the 19th century. It clearly traces the linkage of feminist theory with Marxist theory. It surveys feminist scholarship and praxis on transitional justice with the focus on examination of feminist theories and class and divisions within feminist sexual politics and it also surveys on sexual differences and sexual politics including gender studies, lesbian studies, cultural feminism, radical feminism and socialist feminism.

Keywords: female, Education, Society, Gender, Politics

The term ‘feminism’ is derived from the Latin word ‘Femina’, which means originally “having the qualities of females” says Sushila Singh (31). It began to be used in reference to the theory of sexual equality and the movement for women’s rights, replacing womanism in the 1890’s. Generally speaking, it means “a doctrine advocating social and political rights for women equal to those of men; belief in the necessity of large scale social change in order to increase the power of women” (22). According to Toril Moi, “the word ‘feminism’ or ‘feminists’ are political labels indicating support for the aims of the new women’s movement, which emerged in the late 1960’s” (qtd. in Singh 21). In the words of Teresa Billington Grieg:

Feminism is a movement which seeks the reorganisation of the world upon a basis of sex-equality in all human relations; a movement which would reject every differentiation between individuals upon the ground of Sex, would abolish all sex privileges and sex burden and would strive to set up the recognition of the common humanity of women and men as the foundation of law and custom. (158)

In a broader sense, it may be said that the word ‘feminism’ means an intense awareness of identity as a woman, an interest in feminine problems. Having picked up so many connotations, the word ‘feminism’ was then thought of as a movement for political, social and educational quality for women equated with men and it mainly occurred in Europe and the United States. It is commonly understood that women had been traditionally regarded as inferior to men physically and intellectually resulting in the view that women should not possess property in their names, engage in business or control the disposal of their children or even express their views openly and boldly. However, advocates of equality of the sexes and the rights of women spoke and wrote in support of them. For example, Express Theodora of Byzantium was a proponent of legislation that would afford greater protection and freedom to female subjects. Christine de Pisan was the first feminist thinker to spark off the four century long debate on women which came to be known as “querrelles des fenimes”. Kelley says, “If Petrarch can be called the first modern man, than Christine de Pisan, the poet and author who introduced her countrymen Petrarch and Boccaccio, to Parisian culture in the early 1400 is surely first modern woman” (27).

The defence of women became a literary subgenre by the end of the sixteenth century and the so-called feminists produced a long list of women of courage and accomplishment by proclaiming that women would be intellectual equals of men if they were given equal access to education. The so-called “debate about women” did not reach England at all until the late sixteenth century. Only after a series of satiric pieces, ‘mocking women’ was the first feminist pamphlet written by Jane Anger in England for the protection of women. Only in the 1630’s and 1650’s, many of the radical English sects supported religious equality for women.

Then there were women who effectively liberated themselves from the male clerical authority. They sought to control their own conscience, to preach and improve women’s educational and economic opportunities. These women like Anne Hutchinson were ‘feminists in action’ rather than theorists. Instead of elaborating their ideas in writing, they used them to modify or organise social reforms in which women might be free of male power and authority over them. Their heirs are the women of the late nineteenth and twentieth century revolutionary movements. The feminist theory later gave rise to women’s movements for democratic change. The struggle was carried on mostly by the female members of distinctly modern, literate class representing the upper riches of ranked society. They were the forebears of what Virginia Woolf called “the daughters of educated men” (33). However, the credit for a healthy organised movement for women’s rights goes to America beginning with The Seneca falls Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, drawn and signed at the obscure village Seneca Falls, New York in the summer of 1848. Special support for this historical event came from Elizabeth Cady Stanton. After a heated debate, the convention agreed to acknowledge the rights of American women to elective franchise. A final clause to the Resolution was added by Lucretia urging men and women to work for professional and vocational equality.

Feminism became an organised movement in the nineteenth century as people increasingly came to believe that women were being treated unfairly. The feminist movement was rooted in the Progressive movement and especially in the reform movement of the 19th century. The Utopian Socialist Charles Fourier coined the term ‘feminism’ in 1837 and he argued that the extension of women’s rights underpinned all social progress as early as 1808 (47). Many countries began to grant women the right to vote in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century being first in 1893 with the help of suffragist Kate Sheppard. Little by little, women’s demands for higher education, entrance to trade and professions, married women’s right to property and the right to vote were conceded all over the world. The period from 1920 to 1960 is known as the period of intermission in the history of the women’s rights movement when a sense of complacency prevailed. The reality belied the sense of so-called victory on the issue of suffrage and a New Feminist Movement started in the late 1960’s.

Broadly speaking, the contemporary feminist movement worked for female equality as the earlier nineteenth century feminism had done. In 1946, the UN Commission on the status of women was established to secure equal political rights, economical rights and educational opportunities for women. Milestones in the rise of modern feminism included Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) and Betty Friedman’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and the founding of “The National Organization” in 1966 for Women” (Feminist Studies). In twentieth century, European and American feminism eventually reached into Asia, Africa and Latin America. In the 1980’s feminism emerged as a thought system, a point of view to recognize the world realities positive holistic approach to life, a step towards sanity of human relationship and perhaps the only mode of preservation of human existence on this planet.