Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Graphic Guides

- Sprache: Englisch

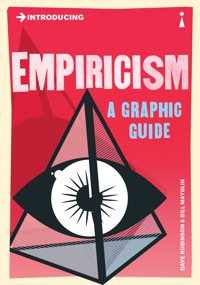

Our knowledge comes primarily from experience – what our senses tell us. But is experience really what it seems? The experimental breakthroughs in 17th-century science of Kepler, Galileo and Newton informed the great British empiricist tradition, which accepts a 'common-sense' view of the world – and yet concludes that all we can ever know are 'ideas'. In Introducing Empiricism: A Graphic Guide, Dave Robinson - with the aid of Bill Mayblin's brilliant illustrations - outlines the arguments of Locke, Berkeley, Hume, J.S. Mill, Bertrand Russell and the last British empiricist, A.J. Ayer. They also explore criticisms of empiricism in the work of Kant, Wittgenstein, Karl Popper and others, providing a unique overview of this compelling area of philosophy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 117

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DPEmail: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-178578-017-2

Text copyright © 2012 Icon Books Ltd

Illustrations copyright © 2012 Icon Books Ltd

The author and illustrator has asserted their moral rights

Originating editor: Richard Appignanesi

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

What is Empiricism?

Knowledge and Belief

Inside and Outside

Originals and Copies

Questions Lead to Uncertainty

To Begin at the Beginning

Aristotle and Observation

Medieval Scholasticism

New Ways of Thinking

Rationalists and Empiricists

Logic and a Deeper Reality?

Francis Bacon

Empiricist Ants and Rationalist Spiders

Scientific Bees and Induction

Bacon, Scientism and Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes’s Leviathan

Hobbes the Empiricist

Locke and Empiricist Theory

Innate Ideas on Blank Sheets

The Empiricist Account

Direct Realism

Differences of Property and Experience

Appearances Are All We Have

Responding to Scepticism

Representative Realism

Mental Images

Simple Ideas

Mental Jamjars

Complex Ideas

Problems of Reflection

Primary and Secondary Qualities

The Philosophy of Corpuscles

Secondary Qualities

Subjective Objects of Sense

Substances Underlying Qualities

The Word “Idea” and Concepts

Concepts as Images

Looking and Thinking

Language as Ideational

Abstract Ideas

Nominal and Real Essences

Identity in Time

Personal Identity

Locke’s Politics

The Legacy of Locke’s Empiricism

Was He Right?

The Prodigy

Berkeley’s Aims

Ending in Scepticism

Berkeley’s Idealism

Esse est Percipi

A New Theory of Vision

Abstract Ideas

Shape and Colour

Triangles

Images of Particulars

Language

How It All Works

Dr Johnson’s Refutation

Berkeley’s Monist Argument

Imagination and Truth

Purely Mental Existence

The Argument from God

The Existence of the Self

Science Depends on God

Space and Numbers

God and Minds

Is Berkeley Irrefutable?

Are the Arguments Convincing?

Begging the Question

God’s Intervention

The Counter-argument from Evolution

David Hume

Hume’s Philosophy of Scepticism

Ideas and Impressions

Impressions and Truth

The Criteria of Force and Vivacity

The External World

Philosophy and Everyday Life

Hume’s Fork

Science, Theology and Proof

The Problem of Cause and Effect

What is Cause?

The Appearance of Constant Conjunction

What is Necessity?

Cause is Psychological and not Logical

Hume Explains “Why”

Induction and Deduction

Rules of Deductive Logic

The Uses of Induction

Solutions to the Problem

The Response of Pragmatism

What About Identity?

Looking Within

Hume on Free Will

Religion, Proof and Design

Ethics, Moral Language and Fact

Meta-Ethics

Conclusions on Hume

Kant’s Criticism of Hume

J.S. Mill’s Empirical Philosophy

The Permanent Possibility of Sensation

Possible Sensations

Why Do We Believe in Objects?

Problems with Mill’s Position

Mathematics

Mill’s Logic

Induction

Mill’s Treatment of Cause

What are Minds?

Mill’s Ethics and Politics

Higher Pleasures

Mill’s Politics

Bertrand Russell

Relative Perception

Sense Data

Russell’s Theory of Knowledge

Logical Atomism

Meaning and Atomic Facts

Mathematics and Logic

A.J. Ayer and the Vienna Circle

Meaning and Logical Positivism

Language Bewitchment

The Isness of Is

Ayer’s Phenomenalism

The A Priori Tautologies

Is This Correct?

Analytic Philosophy

What of Religion?

And Ethics?

Problems with Verificationism

Ayer’s Theory of Meaning

Meaning as Use

The Doctrine Examined

Knowledge Claims

The Foundations of Empiricism

Images as Sense Knowledge

The Knowledge Building

What Does Science Tell Us?

The Person Inside the Head

The Argument from Observer Relativity

Questions of Reliability

A Private World of Representations

How Real Are Sense Data?

The Adverbial Solution

Perceptions as Beliefs

Immediacy

Looking and Seeing

Logical and Psychological Processes

What Do We See?

The Private Language Argument

Public Language

Wittgenstein’s Criticism

The Outside Within Experience

Knowledge in the World

The Power of Knowledge

Kant on Perception

The Kantian Categories

Conceptual Frameworks

Language and Experience

Making Our World

Empiricism Denied

British and European Philosophy

The Unknowable Mind

A Future for Empiricism?

Further Reading

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Index

What is Empiricism?

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT EMPIRICIST PHILOSOPHERS WHO BELIEVE THAT HUMAN KNOWLEDGE HAS TO COME FROM OBSERVATION. MOST EMPIRICISTS THINK THAT IT’S QUITE POSSIBLE THAT ONLY WE EXIST, AND NOTHING ELSE.

Knowledge and Belief

I’m sitting at my computer, after a long day, beginning the first few pages of this book, when without any warning a huge, leathery hippopotamus walks into the room.

THEN I WAKE UP. I’VE BEEN DREAMING. I LOOK AROUND ME, AND THE COMPUTER’S STILL HERE. SO ARE ALL MY BOOKS, GLASSES, A JAR FULL OF PENS, AND A MUG OF COLD TEA. THE SUN IS SHINING OUTSIDE, AND THE TREES ARE MOVING IN THE WIND.

Now I’m confident that I’m awake. Everything I see, hear, smell, touch and taste is real, this time. Knowing about the world through the senses is the most primitive sort of knowledge there is. I couldn’t function without it. But is it possible that I am mistaken, just as I was about the hippopotamus? How certain can I be about my perceptions of trees, jamjars and that cup of cold tea?

Most people assume that the world is pretty much as it appears to them. They believe a cat exists when they see it cross the road. But philosophers are, notoriously, more demanding. They say that beliefs are plentiful, cheap and easy, but true knowledge is more limited, and much harder to justify. This is why philosophers normally begin by separating knowledge from belief.

I PERSONALLY BELIEVE IN THE CONTINUED EXISTENCE OF THIS ROOM AND THE GARDEN OUTSIDE, BUT NOT IN THAT HIPPOPOTAMUS. I ALSO THINK MY BELIEFS ABOUT THE REALITY OF MY IMMEDIATE SURROUNDINGS ARE JUSTIFIED BECAUSE THEY SEEM NATURAL, NORMAL AND OBVIOUS.

That’s enough to convert my beliefs into knowledge. But there is always a slight possibility that I am wrong. The world might not be as I believe it to be. Problems like these worry philosophers called “empiricists”, because they think that private sensory experiences are virtually all we’ve got, and that they’re the primary source of all human knowledge.

Inside and Outside

One thing we do know is that our senses sometimes mislead us. White walls can appear yellow in strong sunlight. Surgeons can stimulate my brain so that I “see” a patch of red that isn’t there. I can have hippopotamus dreams, and so on. My sense experiences are at least sometimes created by my mind – or somehow in my mind. These comparatively rare “mistakes” have led many philosophers to insist that all my perceptions are “mediated”.

WHEN I LOOK OUT OF THE WINDOW, AT THOSE TREES, IT SEEMS TO ME THAT I SEE THEM AS THEY ARE, DIRECTLY.

But I don’t. What I see is a wonderful illusion created by my mind. Of course, I am totally unaware of that fact because my perceptions seem so natural, automatic and rapid. Psychologists tell me that what I actually see is a kind of internal picture, and they devise all sorts of tests and puzzles to prove it.

Originals and Copies

They say that the trees provide me with a “tree sensation” in my mind, and it’s that which I see, not the trees themselves. If that is true, then all I ever see are “copies” of those trees, which I assume are very similar in appearance to the originals.

But, if I think about this even harder, then I realize I have no way of telling how accurate these copies are, because I cannot bypass my mind to take another “closer look” at the originals.

Perhaps the original trees are nothing like the cerebral “copies” at all, or worse still, don’t even exist!

The more I think about perception, the weirder it becomes, and the more I realise that I must be trapped in my own private world of perceptions that may tell me nothing about what is “out there”.

PERHAPS THERE’S JUST ME, AND NOTHING ELSE! SUDDENLY I FEEL DIZZY.

Questions Lead to Uncertainty

This kind of unnerving conclusion is typical of philosophy. You ask simple questions which lead to unsettling bizarre answers.

THAT WHICH I KNEW, I NOW DO NOT KNOW AT ALL. SO IS THERE ANYTHING AT ALL I CAN BE SURE ABOUT?

If there isn’t, how can empiricist philosophers claim that all human knowledge comes from experience? If no one can ever be sure where “experiences” come from in the first place, how reliable are they?

To Begin at the Beginning

Empiricist philosophy is relatively new. Philosophy as such began very differently, with some ancient Greeks called “Pre-Socratic” philosophers who emphasized the differences between appearance and reality. They said that what we see tells us very little about what is real. True knowledge can only come from thinking, not looking. The first truly systematic philosopher, Plato (427–347 B.C.E.), agreed that empirical or sense knowledge is inferior because it is subjective and always changing.

I ONLY BELIEVE THOSE TREES ARE “BIG” BECAUSE THEY’RE SLIGHTLY TALLER THAN MY HOUSE. MY “KNOWLEDGE” OF THOSE TREES IS WHOLLY RELATIVE TO ME. WHAT KIND OF KNOWLEDGE IS THAT? EMPIRICAL KNOWLEDGE CAN ONLY EVER BE A MATTER OF “OPINION” OR “BELIEF”.

Plato turned to mathematics instead. Unlike my trees, numbers are abstract, immune from physical change, the same for everyone, and have a permanence, certainty and objectivity that empirical knowledge lacks. Plato believed that real knowledge had to be like mathematics, timeless and cerebral.

Aristotle and Observation

Plato’s famous student, Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.), disagreed. He thought that it was important to observe the world as well as do mathematics.

I TRIED TO SHOW HOW ALL NATURAL THINGS FUNCTION AS A RESULT OF THE DIFFERENT CAUSES THAT AFFECT THEM.

Aristotle was not a very methodical scientist by our standards. His observations were often tailored to fit his complex metaphysical theories. Much of what he called “physics” was proved wrong.

Medieval Scholasticism

Aristotle’s works resurfaced via Arabic scholarship in 12th-century Western Europe and eventually dominated medieval intellectual life. Western scholars were overawed by the apparent intellectual superiority of Greek philosophy and timidly assumed that human knowledge was virtually complete.

IN THE 13TH CENTURY, I RECONCILED ARISTOTELIAN PHILOSOPHY WITH CHRISTIAN THEOLOGY.

This strange synthesis devised by the Dominican cleric St Thomas Aquinas (1225–74) was subsequently taught in the medieval “schools” or universities and became known as “Scholasticism”. Everyone imagined that philosophy and science had more or less reached a dead-end of perfection.

New Ways of Thinking

Medieval science was more concerned with words and definitions than systematic observation of the world. Attitudes began to change in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Reformation helped to loosen the grip of the Church on intellectual life. Modern scientists like Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) discovered that the universe was not at all as Aristotle had described it. The founder of modern philosophy, René Descartes (1596–1650), described an entirely new kind of science.

CERTAIN KNOWLEDGE DEPENDS ON INTROSPECTION WHICH RECOGNIZES A FEW “CLEAR AND DISTINCT” IDEAS AS NECESSARILY TRUE.

Descartes, like Plato, remained a “Rationalist” philosopher, convinced that scientific knowledge had to derive from mathematics and logic. He was nevertheless a major influence on empiricist philosophers.

The Cartesian model of the mind as a kind of “private room”, and his corresponding theories of perception, reality, knowledge and certainty, seemed persuasive to most empiricist philosophers.

WE ONLY EVER PERCEIVE PRIVATE IDEAS, RATHER THAN THE OUTSIDE WORLD. KNOWLEDGE HAS TO BE ASSEMBLED GRADUALLY, FROM THE INSIDE OUT.

Rationalists and Empiricists

Rationalist philosophers maintain that reason is the most reliable source of knowledge. “Knowledge comes from thinking, not looking.”

Geometry provides the best systematic example of infallible, permanent knowledge based wholly on deduction. But empiricists” claim that, although geometrical and mathematical forms of knowledge are “necessary”, they are only reliable because they are “trivial”. Logic and mathematics do no more than “unpack” or clarify the inevitable consequences of a few preliminary definitions or axioms.

THE ANGLES OF A TRIANGLE HAVE TO ADD UP TO 180 DEGREES – IF YOU ACCEPT THAT THE SHORTEST DISTANCE BETWEEN TWO POINTS IS A STRAIGHT LINE, AND A FEW OTHER AXIOMS. AND, IF ALL CATS HAVE WHISKERS, AND THIS IS A CAT, THEN IT MUST HAVE WHISKERS. BUT THIS IS A CONCLUSION DERIVED FROM WORDS, NOT CATS.

Logic and a Deeper Reality?

Empiricists say that neither geometry nor logic will tell you anything about the real world. The cerebral wonders of mathematics and logic are like chess – “closed” and “empty” systems constituted by their own sets of rules.

REAL KNOWLEDGE HAS TO ORIGINATE FROM SENSORY EXPERIENCES AS OUR ONLY GUIDE TO WHAT IS ACTUALLY TRUE.

There is no magical way of going beyond the limits of what we can see, hear, taste, smell and touch.

Later historians have often imagined a kind of “war” between the down to earth British “Empiricists” like Locke, Berkeley and Hume, and the more fanciful “Rationalist” continentals, like Descartes, Spinoza and Leibniz. But this controversy was not very real for those supposedly taking part. Few would have considered themselves stuck in either opposed “camp”. The labels “Empiricist” and “Rationalist”, although useful, can obscure the actual views of individual philosophers.

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon (1561–1626) was a lawyer who eventually became Lord Chancellor. He was a corrupt politician, as well as a devoted scholar. He was obsessed with learning, of all kinds, and put forward several schemes for public libraries, laboratories and colleges. (The most famous is “Solomon’s House” in his book New Atlantis.) Bacon believed in scientific progress, even though he was constantly aware of the limitations of human knowledge.

MEN MUST SOBERLY AND MODESTLY DISTINGUISH BETWEEN THINGS DIVINE AND HUMAN, BETWEEN THE ORACLES OF SENSE AND FAITH.

Bacon thought that a methodical and detailed observation of the world would massively increase the scope of human knowledge. It was only by studying the world’s complex design that we would learn about its designer, God.

Empiricist Ants and Rationalist Spiders

Bacon was scathing about scholars who worshipped past “authorities” and obscured the “advancement of learning”. Medieval “scientists” spent too long in libraries, arguing about definitions. Real science meant investigating the world outside.

BUT THERE IS MORE TO SCIENCE THAN ACCUMULATING FACTS. KNOWLEDGE CAN ONLY ADVANCE WHEN OBSERVATIONS HAVE SOME POINT TO THEM.

Scientific Bees and Induction

Successful “natural philosophers” are like sensible “bees”. Their methodical collections of information stimulate theory, give rise to experiments, and produce the “honey” of scientific wisdom. Bacon devised a whole series of procedural methods for ambitious bee-scientists.

I RECOGNIZED THE IMPORTANCE OF INDUCTION AS A METHOD OF RESEARCH AND A WAY OF STIMULATING THEORY.