4,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Edizioni Aurora Boreale

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

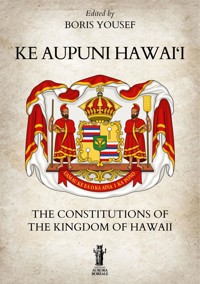

The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (

Ke Aupuni Hawaiʻi), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent island of Hawaiʻi, conquered the islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokai and Lānaʻi and unified them under one government. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauaʻi and Niʻihau joined the Hawaiian Kingdom voluntarily. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

The kingdom won recognition from the major European powers and the United States became its chief trading partner. In 1887 King Kalākaua was forced to accept a new constitution in a coup by the Honolulu Rifles, an anti-monarchist militia. Queen Liliʻuokalani, who succeeded Kalākaua in 1891, tried to abrogate the new constitution. She was overthrown in 1893, largely at the hands of the Committee of Safety. Hawaiʻi was briefly an independent republic until the U.S. annexed it through the Newlands Resolution on July 4, 1898, which created the Territory of Hawaiʻi.

Historian Boris Yousef presents in this essay the five constitutions of the Kingdom of Hawaii, from that of 1840 to the one, which never entered into force, of 1893.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

SYMBOLS & MYTHS

Edited by

BORIS YOUSEF

KE AUPUNI HAWAI‘I

THE CONSTITUTIONS OF

THE KINGDOM OF HAWAII

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Title: Ke Aupuni Hawai‘i. The Constitutions of the Kingdom of Hawaii

Edited by Boris Yousef

Publishing series: Symbols & Myths

ISBN: 979-12-5504-343-0

Edizioni Aurora Boreale

© 2023 Edizioni Aurora Boreale

Via del Fiordaliso 14 - 59100 Prato - Italia

www.auroraboreale-edizioni.com

INTRODUCTION

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Ke Aupuni Hawaiʻi), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent island of Hawaiʻi, conquered the independent islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokai and Lānaʻi and unified them under one government. In 1810, the whole Hawaiian archipelago became unified when Kauaʻi and Niʻihau joined the Hawaiian Kingdom voluntarily. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom: the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

The kingdom won recognition from the major European powers. The United States became its chief trading partner and watched over it to prevent other powers (such as Britain and Japan) from asserting hegemony. In 1887 King Kalākaua was forced to accept a new constitution in a coup by the Honolulu Rifles, an anti-monarchist militia. Queen Liliʻuokalani, who succeeded Kalākaua in 1891, tried to abrogate the new constitution. She was overthrown in 1893, largely at the hands of the Committee of Safety, a group including Hawaiian subjects and resident foreign nationals of American, British and German descent, many educated in the United States. Hawaiʻi was briefly an independent republic until the U.S. annexed it through the Newlands Resolution on July 4, 1898, which created the Territory of Hawaiʻi. United States Public Law 103-150 of 1993 (known as the Apology Resolution), acknowledged that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States" and also "that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi or through a plebiscite or referendum".

In ancient Hawaiʻi, society was divided into multiple classes. At the top of the class system was the aliʻi class with each island ruled by a separate aliʻi nui. All of these rulers were believed to come from a hereditary line descended from the first Polynesian, Papa, who would become the earth mother goddess of the Hawaiian religion. Captain James Cook became the first European to encounter the Hawaiian Islands, on his third voyage (1776–1780) in the Pacific. He was killed at Kealakekua Bay on the island of Hawaiʻi in 1779 in a dispute over the taking of a longboat. Three years later the island of Hawaiʻi was passed to Kalaniʻōpuʻu's son, Kīwalaʻō, while religious authority was passed to the ruler's nephew, Kamehameha.

The warrior chief who became Kamehameha the Great, waged a military campaign lasting 15 years to unite the islands. He established the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1795 with the help of western weapons and advisors, such as John Young and Isaac Davis. Although successful in attacking both Oʻahu and Maui, he failed to secure a victory in Kauaʻi, his effort hampered by a storm and a plague that decimated his army. Eventually, Kauaʻi's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha (1810). The unification ended the ancient Hawaiian society, transforming it into an independent constitutional monarchy crafted in the traditions and manner of European monarchs. The Hawaiian Kingdom thus became an early example of the establishment of monarchies in Polynesian societies as contacts with Europeans increased. Similar political developments occurred in Tahiti, Tonga, Fiji and New Zealand.

The Royal Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Hawaii

From 1810 to 1893 two major dynastic families ruled the Hawaiian Kingdom: the House of Kamehameha (to 1874) and the Kalākaua dynasty (1874-1893). Five members of the Kamehameha family led the government, each styled as Kamehameha, until 1872. Lunalilo (r. 1873-1874) was also a member of the House of Kamehameha through his mother. Liholiho (Kamehameha II, r. 1819-1824) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III, r. 1825-1854) were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great.

During Liholiho's (Kamehameha II) reign (1819-1824), arrival of Christian missionaries and whalers accelerated rapid changes in the kingdom.

Kauikeaouli's reign (1824-1854) as Kamehameha III, began as a young ward of the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Kaʻahumanu, who ruled as Queen Regent and Kuhina Nui, or Prime Minister until her death in 1832. Kauikeaouli's rule of three decades was the longest in the monarchy's history. He acted on the Mahele land revolution of 1848, promulgated the first Constitution (1840) and its successor (1852) and witnessed cataclysmic losses of his people through Western-introduced diseases.

Until the change from the Kamehameha dynasty to the Kalakaua dynasty (1874), the ruling monarchs' tenures were short-lived. Alexander Liholiho, Kamehameha IV, (r. 1854-1863), introduced Victorian Anglican religion and royal habits to the kingdom.

Lot, Kamehameha V (r. 1863-1872), who ruled under pressure from rapidly expanding American sugar production, struggled to solidify Hawaiian nationalism in the kingdom.

William Lunalilo (r. 1873-74), cousin of Kauikeaouli and Lot, was the first elected Hawaiian monarch. Upon his death, David Kalakaua defeated Kamehamehameha IV's wife, Queen Emma, in a contested election for the dynastic change.

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family ended in 1872 with the death of Kamehameha V. On his deathbed, he summoned High Chiefess Bernice Pauahi Bishop to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. Bernice refused the crown, and Kamehameha V died without naming an heir.

The refusal of Bishop to take the crown forced the legislature of the kingdom to elect a new monarch. From 1872 to 1873, several relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In the monarchical election of 1873, a ceremonial popular vote and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo, grandnephew of Kamehameha I, became Hawaiʻi's first of two elected monarchs but reigned only from 1873 to 1874 because of his early death due to tuberculosis at the age of 39.

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom needed an election to fill the royal vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kalākaua. The 1874 election was a nasty political campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. David Kalākaua became the second elected King of Hawaiʻi but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice of the legislature was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the Emmaites.

Kalākaua officially proclaimed his sister, Liliʻuokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty in the monarchy's future, Kalākaua had named a line of succession in his will, so that after Liliʻuokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Kaʻiulani, then to Queen Consort Kapiʻolani, followed by her sister, Princess Poʻomaikelani, then Prince David Laʻamea Kawānanakoa and last was Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole. Although, the will was not an official line of succession or a proper proclamation according to kingdom law. There were also protests about nominating lower ranking aliʻi after Kaʻiulani who were not eligible to the throne while there were still high ranking aliʻi who were eligible, such as High Chiefess Elizabeth Kekaʻaniau. However, it was now the royal prerogative of Queen Liliʻuokalani and she officially proclaimed her niece Princess Kaʻiulani as heir to the throne. She then later proposed a new constitution adding Prince David Kawānanakoa and Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, according to the wishes of Kalākaua, but it was never approved or ratified by the legislature.

Kalākaua's prime minister Walter M. Gibson indulged the expenses of Kalākaua and attempted a Polynesian confederation sending the "homemade battleship" Kaimiloa to Samoa in 1887. It resulted in suspicions from the German Navy and embarrassment for the conduct of the crew.

In 1887, a constitution was drafted by Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of Interior under King Kalākaua. The constitution was proclaimed by the king after a meeting of 3,000 residents including an armed militia demanded he sign it or be deposed. The document created a constitutional monarchy like the one that existed in the United Kingdom, stripping the King of most of his personal authority, empowering the legislature and establishing a cabinet government. It has since become widely known as the "Bayonet Constitution" because of the threat of force used to gain Kalākaua's cooperation.

The 1887 constitution empowered the citizenry to elect members of the House of Nobles (who had previously been appointed by the King). It increased the value of property a citizen must own to be eligible to vote above the previous Constitution of 1864 and denied voting rights to Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population (a few Japanese and some Chinese had previously become naturalized and now lost voting rights they had previously enjoyed). This guaranteed a voting monopoly to wealthy native Hawaiians and Europeans. The Bayonet Constitution continued allowing the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but stripped him of the power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.

In 1891, Kalākaua died and his sister Liliʻuokalani assumed the throne. She came to power during an economic crisis precipitated in part by the McKinley Tariff. By rescinding the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, the new tariff eliminated the previous advantage Hawaiian exporters enjoyed in trade to U.S. markets. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens were feeling the pressures of the loss of revenue, so Liliʻuokalani proposed a lottery and opium licensing to bring in additional revenue for the government. Her ministers and closest friends tried to dissuade her from pursuing the bills, and these controversial proposals were used against her in the looming constitutional crisis.

Liliʻuokalani wanted to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Constitution. The queen launched a campaign resulting in a petition to proclaim a new Constitution. Many citizens and residents who in 1887 had forced Kalākaua to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" became alarmed when three of her recently appointed cabinet members informed them that the queen was planning to unilaterally proclaim her new Constitution. Some cabinet ministers were reported to have feared for their safety after upsetting the queen by not supporting her plans.

King Kalākaua meeting U.S. President Grant at the White House in 1874

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians, composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national, all of whom were living and doing business in Hawaiʻi, overthrew the queen, her cabinet and her marshal, and took over the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Historians suggest that businessmen were in favor of overthrow and annexation to the United States in order to benefit from more favorable trade conditions with its main export market. The McKinley Tariff of 1890 eliminated the previously highly favorable trade terms for Hawaiʻi's sugar exports, a main component of the economy.

The King of the Hawaii Kalākaua (David Laʻamea Kamananakapu Mahinulani Naloiaehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua)