Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

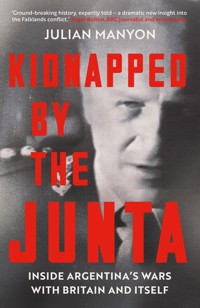

'Heart-thumpingly powerful ... history told from the closest and most frightening quarters.' SINCLAIR MCKAY, author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park 'Shocking, terrifying and revealing. Ground-breaking history, expertly told - a dramatic new insight into the Falklands conflict.' ROGER BOLTON, BBC journalist and broadcaster Forty years on from the outbreak of the war, acclaimed TV journalist Julian Manyon digs down into Argentina's 'Dirty War' and its effect on the Falklands conflict On May 12th, 1982, after the first bloody exchanges of the Falklands War, journalist Julian Manyon and his TV crew were kidnapped on the streets of Buenos Aires and put through a traumatic mock execution by the secret police. Less than eight hours later they were invited to the Presidential Palace to film a world-exclusive interview with an apologetic President Galtieri, the dictator and head of the Argentine Junta. Spurred on by the recent release of declassified CIA documents about Argentina's 'Dirty War', Manyon discovered that his kidnapper was a key figure in the Junta's bloody struggle against left-wing opposition, with a terrifying record of torture and murder. Also in the secret documents were details of the wider picture - the turmoil inside the Junta as the war with Britain got under way, and how Argentina succeeded in acquiring vital US military equipment which made its war effort possible. Published on the 40th anniversary of the Falklands conflict, this book is an extraordinary insight into the war behind the war. Manyon provides a harrowing depiction of the campaign of terror that the Junta waged on its own population, and a new perspective on an episode of history more often centred on Mrs Thatcher, the Belgrano and the battle of Goose Green.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 487

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for Kidnapped by the Junta

‘Julian Manyon’s heart-thumpingly powerful book is history told from the closest and most frightening quarters. He was both witness and near-victim to the darkness that enveloped Argentina in the 1970s and 1980s. And now, across the gulf of the years, and with fresh access to fascinating documentation, he records the carnage of the Falklands War of 1982, kicking away many widely held assumptions. His account of state terror and global geopolitics is by turns pulse-quickeningly tense and richly illuminating.’

Sinclair McKay, author of The Secret Life of Bletchley Park

‘Shocking, terrifying and revealing. Ground-breaking history, expertly told – a dramatic new insight into the Falklands conflict.’

Roger Bolton, BBC journalist and broadcaster

‘Drawing on a huge tranche of recently declassified US documents, Julian Manyon authoritatively nails the Argentine Junta’s regime as one of the most depraved and deluded of modern times. After reading this book, packed with so much graphic new detail, I feel more fortunate than ever to have escaped Argentina with my life.’

Ian Mather, former defence correspondent of The Observer

‘A gripping story, brilliantly told … a compelling account of a dark period of modern history.’

Stephan Shakespeare, founder and CEO of YouGovii

iii

Contents

iv

To my son Richard for his steady encouragement throughout and to my dear wife Caroline without whose help this book could not have been completed.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julian Manyon was a journalist specialising in international stories for more than 40 years, starting in Vietnam. He covered the Falklands War in Argentina for Thames Television’s TV Eye and then became a long-serving foreign correspondent for ITN, winning numerous awards for his work. He lives with his wife on their small farm in the south of England.

List of illustrations

Interviewing President Leopoldo Galtieri hours after the kidnapping.

A secret report by the CIA stating that the kidnapping had been done by ‘a paramilitary group’ linked to the secret service.

The first military Junta which seized power in March 1976.

The Junta which lost its war with Britain.

Uniformed troops and police suppress dissent in the streets.

A massive demonstration in support of the Junta’s seizure of the Falkland Islands.

Mothers and Grandmothers of the ‘disappeared’ protest in the Plaza de Mayo.

Aníbal Gordon, kidnapper, torturer and murderer, soon after his arrest in 1984.

Allen ‘Tex’ Harris, the American diplomat appalled by the regime’s use of torture and murder.

Mario Firmenich, leader of the Montoneros revolutionary group.x

HMS Antelope sinks after the detonation of two unexploded bombs.

Argentinian soldiers captured at Goose Green are guarded by a British Royal Marine.

Automotores Orletti, where Aníbal Gordon ran a secret torture and murder centre.

The cellar at 3570 Bacacay Street where victims are said to have been tortured.

Intelligence officer and torturer Miguel Ángel Furci awaits sentencing in a Federal Court.

CHAPTER 1

Swallowed

Amid all the dramas of the career in journalism that I had so much desired, I had not expected to have an hour to contemplate my own imminent execution.

As the car rolled forward at a deliberately steady pace, I lay constrained and helpless on my back in the rear footwell, a cloth over my head blocking almost all vision, a man’s knee jammed against my neck pinning my head against the back of the seat in front and a hard, tanned hand holding an automatic pistol pressed against the side of my head.

The words were in Spanish but even with my fragmentary knowledge of the language I could understand them. ‘Quiet,’ the harsh voice said, and then with a short gesture of the pistol, ‘When we get where we are going, I will kill you with this.’

It was May 12th, 1982, in the age before training courses in hazardous environments and psychological counselling. As I briefly reflected on the mess in which I found myself, only unhelpful thoughts occurred.

I had been close to death before. So determined had I been to become an international journalist that more than a decade earlier I 2had launched myself as a freelance in Vietnam. There, following the American invasion of Cambodia in a battle too obscure for mention in the history books, I had survived the destruction of a Cambodian Army battalion by the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong, as untrained Cambodian youngsters were ambushed and shot down by terrifyingly effective NVA regulars charging with fixed bayonets. As night fell an American airborne gunship trying to save their allies added to the chaos and terror by firing long red streams of tracer fire, which appeared suddenly and silently in the darkness, followed by a deafening roar as the sound of the machine guns caught up. I had saved myself by playing dead while communist troops sprinted past around me, and I found out in that paddy field what it is to tremble uncontrollably. In the end, as dawn broke, I was able to crawl out alive.1

This was different but, if anything, even more terrifying: a slow steady progress through moving traffic in the streets of Buenos Aires as I lay helpless and unable to affect my fate in any way. In the jargon of the Argentinian secret police which I learned later, I had been ‘swallowed’ and ‘walled in’.

There were three men in the saloon car that carried me: the driver, a man in the front seat operating a radio on the dashboard and the man holding the gun to my head who appeared to be their commander. Brief incomprehensible radio messages were occasionally exchanged.

One thing was very clear: the men who had seized me and who now held my life in their hands were professionals in the art of kidnapping. In the early afternoon, together with the other members of our British television team, I had emerged from the Argentine Foreign Ministry after a failed attempt to interview Minister Nicanor Costa Méndez, the Oxford-educated civilian described by some as 3the ‘evil genius’ of the military regime. Costa Méndez, who walked with the aid of a stick, had been angered by the press of journalists and my insistent questions and brushed us off with an infuriated wave of the hand. Minutes later, as we stepped into the tree-lined square outside the handsome colonial-style building and got into our car, I was suddenly swept up in a series of events that seemed to happen in slow motion but in reality occurred at lightning speed: another car, which I remember as being grey in colour, cut in front of us forcing us to stop and disgorged strongly-built men clad in sharp suits. They seized me with firm hands while shouting, ‘Police!’ Suddenly I was looking up at trees we had been passing and, before I could make any real attempt at resistance, I was propelled into the back of their vehicle. A pistol was pressed against my head. I had no idea what was happening to the rest of the team. I just knew that they weren’t there.

The doors slammed shut and in a motion that immediately terrified me, the men produced what appeared to be custom-made leather thongs with which they expertly tied the door handles to the door locks in this pre-electronic vehicle. As I dimly realised amid the shock and mounting panic, this made it virtually impossible for me or any other victim, no matter how desperate, to kick open a door. It was a practised routine which these men had clearly carried out many times before.

The car, built by the Ford factory in Argentina, was called a Falcon, a solid, practical model that was already notorious as the vehicle of choice of the secret police. It moved quietly through the streets which despite the war with Britain were choked with traffic. As was their aim, the kidnappers had achieved complete control. Resistance was beyond my power and would, in any case, have been futile and probably fatal. From beneath the cloth covering my 4head I caught occasional glimpses of the upper storeys of some of the buildings we were passing, the fine old ones in the centre, then more modern structures as we began to move towards the outskirts of the city.

Suddenly I saw gantries carrying familiar yellow signs advertising the Lufthansa airline and realised that we were passing the international airport where we had arrived some ten days before.

‘Look,’ I said in broken Spanish-English to the man holding the gun to my head, ‘In my pocket I’ve got dollars. Please take the money and throw me out here.’

No word came in reply but I felt a horny hand force its way into my trouser pocket searching for the money, some $800, which he silently removed. Without the slightest change of pace, the car rolled on. When I made another attempt to speak I was silenced with a slap. Then, as our car seemed to move through traffic, my knees were struck with the pistol butt to make me pull them down beneath the level of the window.

But as my kidnapper scrabbled for the money he had given me a brief glimpse of his face. I was too frightened to look at him calmly with a view to recall but something remained lodged in my memory all the same.

295Notes

1. The destruction of the Cambodian Army battalion I was accompanying took place on November 23rd, 1970 near the town of Skoun, north of the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh. United Press International reported on the battle and my escape on November 24th.

CHAPTER 2

War

In May 1982 the eyes of the world were fixed on events taking place at one of the most remote and obscure points on the planet. So little-known were the Falkland Islands that some of the British servicemen hastily dispatched there had initially believed that they were being sent to islands north of Scotland rather than to the middle of the South Atlantic. Even the then Defence Secretary, Sir John Nott and the Chief of the General Staff, Lord Bramall, later confessed to similar ignorance when they both told a seminar in June 2002 that at the outset they had had no clear idea of exactly where the islands lay.1

In my case, though claiming no greater knowledge, I was at least in the right continent when the crisis erupted in late March. Together with a crew from Thames Television’s current affairs programme TV Eye I was filming a report on the elections in war-torn El Salvador, the second time I had been sent to that beautiful, unfortunate land on the north-west coast of Latin America. Our team included cameraman Ted Adcock, a dashing figure and winner of awards for his work, soundman Trefor Hunter, quiet, reserved and highly professional, and our producer, Norman Fenton, a canny, 6bearded, Scots-accented veteran of the television industry. Together we filmed blown bridges and murder victims lying in the street and took cover as an election office came under fire. Then came a telephone call from our Editor in London.

Mike Townson was a man possessed of a curious charisma with his stocky, overweight frame and heavy lips. He had always reminded me of a tribal chieftain making his dispositions from the substantial chair behind his desk. Now his instructions were brisk and to the point. Some Argentines had landed on a British-owned island called South Georgia. It was becoming an international crisis. We should leave El Salvador immediately and head for Buenos Aires. ‘Try to keep out of trouble,’ he said helpfully.

We had no idea how British journalists would be received in Argentina and it was agreed that our team would split up and make our way there by different air routes, in my case via Miami and Santiago in Chile. In fact, even though our journey took place just as Argentine troops were landing on the Falkland Islands, we experienced no difficulty with passport control or customs in Buenos Aires and were soon reunited. Following journalistic instinct, we quickly boarded yet another aircraft and flew to Comodoro Rivadavia, a southern oil town in Argentina’s tapering cone that ends near Antarctica and one of the key locations from which the invasion of the Falklands was being staged. There we had our first brush with the reality of trying to cover events in a country with which Britain was now effectively at war.

Within a few minutes of our arrival in the somewhat barren settlement, we were arrested by secret policemen dressed in plain clothes and equipped with pistols and walkie-talkies. They told us that Comodoro Rivadavia was now a military zone and escorted us to a local hotel where, as soon as we checked in, all the telephones were 7cut off to prevent us making outside calls. We were then told that we must leave the area by 10am the following day. Early next morning, in our desire to get at least a few images from the trip, we attempted to film a view of the ocean, looking in what we imagined was the direction of the Falkland Islands, and were immediately arrested by armed soldiers. Fortunately they were appeased by our promise to leave the town and we were permitted to return to the local airport, where we saw exactly why security was on such high alert. The runway was now lined with troops with their packs and rifles waiting to board C-130 transport aircraft for their flight to the Falklands. It was visual evidence that the Argentine Junta had no intention of backing down and was instead doubling up on its bet of seizing the islands.

We were able to fly back to Buenos Aires and in retrospect had been extremely fortunate. A few days later, three other British journalists, Simon Winchester of The Sunday Times and Ian Mather and Tony Prime of The Observer, ventured even further south and were also arrested. However, they were charged with espionage and spent the next twelve weeks as the war was fought sharing a cell in an unattractive Argentine prison which also housed thieves and murderers. It has occurred to me to wonder whether the relative ease of our own return to the capital produced in my case a certain over-confidence that contributed to our later near-disaster.

With the clarity of hindsight we were dangerously naive. Reporting on a war from the enemy’s capital held obvious perils, but even as the British task force assembled and set out we were among those prey to the widespread belief that this confrontation would end without serious bloodshed. Our first days in Buenos Aires only served to strengthen the sense of unreality.

Even as the crisis gathered pace the Argentine capital remained a captivating city which symbolised the country’s extraordinary 8history: the elegant centre with its fine French-style neo-classical buildings, punctuated by florid Art Nouveau masterpieces, all products of the astonishing building boom between 1880 and 1920 when Buenos Aires was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world and Argentina, fuelled by its vast agricultural hinterland, seemed destined to become one of the world’s richest countries.

It was a land originally seized by Spanish soldiers and fortune-hunters who had exterminated or driven out most of its indigenous Amerindians – now just 2% of the population – and was then filled by waves of European immigrants ranging from Italian slum-dwellers to English landowners, Russians trying to escape Tsarism or revolution and yet more Spaniards, often peasants from Galicia or the Basque country. There were also Japanese hungry for opportunity who set up their own Spanish-speaking tribe. In similar fashion to the United States, this was a country built by tough-minded incomers and indeed the sheer volume of immigration was second only to the US. The resulting architectural styles of Buenos Aires reflect the utopian ambitions of the designers as well as their foreign heritage, and speak more to aspiration than to a reality in which boom was regularly followed by crushing economic bust. On Avenida Rivadavia, named after the first President of Argentina, we saw the two splendid Gaudí-influenced masterpieces: the Palace of the Lilies and the other fine building next door, which bears on its façade a legend reading, ‘There are no impossible dreams’. But in the outlying areas beyond the centre, the miles of often crudely built housing and commercial blocks testified to the struggles and disappointments of what was painfully becoming a Latin American megapolis.

In May 1982, as the British task force sailed towards the Falklands – or as Argentines call them Las Malvinas, using the name given to them by French explorers who were in fact the first to settle 9the islands – many in Buenos Aires found themselves dreaming of national fulfilment. Raising the Argentine flag over those windswept outcrops would finally transcend dictatorship, terrorism and the never-ending economic crisis in which inflation had reached 150% and the peso was almost valueless. There was intoxicating drama in the rallies in front of the Presidential Palace, the Casa Rosada or Pink House, known in the Anglophone community as the Pink Palace, where General Leopoldo Galtieri, leader of the military Junta who had ordered the seizure of the islands after only four months in power, appeared on a balcony in the style of Argentina’s earlier celebrated leader Juan Perón and delivered a nationalist clarion call to a vast, excited crowd. In the streets were columns of cars with drivers flying the Argentine flag and sounding their horns, and all over the city an excited buzz fed off the newspaper headlines announcing Argentina’s preparations for air and naval war and the certainty of their victory. I was welcomed to the offices of the leading newspaper Clarín by its Foreign Editor Roberto Guareschi, as the paper’s journalists pounded the metal typewriters of that era to produce yet more optimistic copy. In remarks that were typical of the coun-try’s mood but seem tragically out of touch in the light of events, Guareschi told me that Margaret Thatcher and the British government appeared confused: ‘They don’t know whether to use force or not. First they say they might use it. Then they say they wouldn’t use it. I guess that all this is only to be tough before negotiations …’

Like many Argentines Mr Guareschi had convinced himself that Mrs Thatcher would negotiate a settlement: ‘I don’t give much importance to the public British proposals,’ he told me. ‘I guess that in the end at the negotiation table the proposals will be more realistic.’

Argentines with an interest in history like our excellent interpreter/researcher Eduardo harked back to another war in the early 101800s between British troops and the Spanish colony that is now Argentina, a war that is completely forgotten in Britain but is taught religiously to every Argentinian schoolchild. Two successive attacks were launched by a British force that had been granted extraordinary freedom of action by London. In the spirit of those times it was an openly piratical mission seeking commercial control not of a few remote islands but of the increasingly prosperous area around the River Plate and the growing hub of Buenos Aires itself. The assault was driven on by reports that a large shipment of Peruvian silver had just arrived in the town but, contrary to the expectations of the operation’s commanders who had hoped to enrich themselves with prize money and had even reached agreement on how to divide it, they met with fierce resistance from local militias and, in the end, suffered a crushing defeat. ‘People here are not that soft, effeminate race they are in old Spain,’ a British officer said ruefully. ‘On the contrary they are ferocious.’2

Now hailed in Argentina as a landmark victory, the war with Britain opened the way for the country to declare independence from Spain nine years later in 1816.

In 1833 Britain successfully asserted her naval power by seizing full control of the Falkland Islands, where the British had first landed more than 100 years earlier, and removing some of the small number of Argentinians who had settled there. For the now-powerful British Empire this was little more than a geopolitical footnote that scarcely registered in the public’s consciousness, but for the new nation of Argentina it became a running sore. Economic relations between Britain and Argentina grew and prospered, with Britain for many years effectively controlling the Argentine economy, but Argentines continued to hark back to their first triumphs over the redcoats. The bodies of several hundred British soldiers, mostly 11Scottish Highlanders, are said to be buried under Avenida Belgrano in central Buenos Aires and the colours of the British 71st Regiment of Foot, together with two Royal Navy banners, are still held at the Santo Domingo convent. In 1982 the lesson that many Argentines drew from this was that victory over Margaret Thatcher’s task force, however well-equipped and heavily armed, was possible.

Lucia Galtieri, the wife of the dictator, attended prayers at a church which was a bastion of resistance to the British Army in 1806. Afterwards she told us of the emotional attachment Argentinians felt for the islands: ‘The Malvinas are not just a myth. They are a longing, a desire … Everybody in Argentina agrees that the Malvinas should again become part of our national patrimony.’

‘Las Malvinas son argentinas’ were the words on every lip and, a little surprisingly, they were often accompanied by smiles of welcome when we identified ourselves as British journalists seeking to report their views of the war.

Above all the city itself still had the energy for which Buenos Aires was famous. This, as any Argentine would tell you, was the country that had produced Formula One’s greatest racing driver in Juan Manuel Fangio, five times world champion in the tourna-ment’s first decade, as well as footballers who had won the World Cup and dazzled soccer fans everywhere, a country which each year on December 11th celebrates a national day of Tango. At the end of April 1982, cafes were packed and restaurants full of people feasting on the country’s legendarily massive and surprisingly tender steaks washed down by flagons of hearty red wine, an elixir which for many bred ebullient optimism. The military men we were able to interview were more restrained in their assessments but absolutely uncompromising in the message they wished to convey. Admiral Jorge Fraga, a cheerful balding expert in sea warfare from the Argentine Naval 12College, claimed to be heartened by the relatively small size of the British task force, which included fewer than 5,000 combat troops in defiance of the traditional military formula, which would give the Argentine soldiers now entrenched in the Falklands a key strategic advantage. His thinking clearly reflected the beliefs of the military Junta which he served: ‘You know that invasion needs seven soldiers attacking for each one defending, so I think that to have success the British will need about 40,000 soldiers. If not they will lose men and ships and maybe suffer disaster.’

I then asked him a question which seemed obvious even before the events that followed. Could the result in fact be a disaster for the Argentine Navy? I received a chilling reply: ‘Maybe our Navy too,’ he said, ‘but our objective is to stay in the islands and we are going to stay.’

Prayers and rhetoric were soon to be replaced by the frightening drumbeat of war. On May 1st a giant RAF Vulcan bomber, flying at extreme long range from Ascension Island with the help of repeated air-to-air refuelling, struck Port Stanley airfield and cratered the runway with one of its 1,000lb bombs. This was followed by another raid on the airfield by Royal Navy Sea Harriers. Hours later, Argentinian Air Force jets attacked the Royal Navy task force, causing limited damage to two British ships. Twenty-four hours after that, the Royal Navy struck in clinical and devastating fashion. The antiquated Argentine cruiser General Belgrano was torpedoed and sent to the bottom by the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror with the loss of 323 lives.

Britain’s sinking of the Belgrano has been hotly debated, a debate which continues to this day. Was the out-of-date warship – which as the USS Phoenix had survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and then served in the Pacific theatre throughout the Second World 13War before being sold to Argentina – sailing towards the British task force or away from it? Did it constitute a threat that required a British nuclear submarine to fire torpedoes which blew a massive hole in the side and cut the warship’s electrical power supply, making any attempt to pump out the millions of gallons of onrushing seawater impossible? Was it significant that the Belgrano was outside the naval exclusion zone which Britain had declared, in light of London’s warning that even ships outside it could be attacked? Was this a British war crime or was the Argentine Admiral Juan Lombardo, the Commander of the South Atlantic theatre of operations, who the day before had ordered all naval forces to attack the British, guilty of sending hundreds of his seamen to their deaths through a naive underestimation of the Royal Navy’s strength? How much weight should be given to the statement by the Belgrano’s commander, Captain Hector Bonzo, who said in a later interview, ‘It was absolutely not a war crime. It was an act of war, lamentably legal’?3

I do not intend to contribute to this argument, which reached a bitter climax when Mrs Thatcher’s husband Denis accused BBC producers of being ‘Trots’ and ‘wooftahs’ after they broadcast a celebrated television confrontation between the Prime Minister and a critical and well-informed member of the public a year after the sinking. What I can personally testify to is the surge of shock and grief which ran through Buenos Aires when reports of the sinking were confirmed after being initially denounced as ‘lies’ by the Junta. At our hotel young women, who normally worked there cheerfully, appeared close to tears. It took almost 48 hours for what had happened to become clear, hours in which men struggled and drowned or froze to death in the chill waters of the South Atlantic, hours in which a terrible pall of sorrow and growing apprehension hung over the city. 14

On May 4th the Argentine government issued a statement on the sinking:

At 17 hours on 2 May, the cruiser ARA General Belgrano was attacked and sunk by a British submarine in a point at 55° 24′ south latitude and 61° 32′ west longitude. There are 1,042 men aboard the ship. Rescue operations for survivors are being carried out …

That such an attack is a treacherous act of armed aggression perpetrated by the British government in violation of the UN Charter and the ceasefire ordered by United Nations Security Council Resolution 502 …

That in the face of this new attack, Argentina reiterates to the national and global public its adherence to the ceasefire mandated by the Security Council in the mentioned resolution.

In fact diplomacy was already failing with the unsuccessful visit and brusque departure of the US Secretary of State Alexander Haig and it rapidly became clear that what the Junta meant by adherence to a ceasefire was, in reality, bloody retaliation. Even as the government’s statement was distributed to journalists a pair of Argentina’s most advanced aircraft, the French-built Super Étendards, headed for the British task force carrying two of the country’s small stock of five lethal missiles, the name of which soon entered the English lexicon, the Exocet. As one of the pilots popped up from sea-skimming level to fix the target, the ship he locked on to was the destroyer HMS Sheffield. The results shocked Britain and the world. Twenty Royal Navy sailors died and the ship, which had cost £25 million in 1971, was wrecked and then lost when it sank while under tow.15

In Buenos Aires a jubilant Junta turned on the printing presses to rush out thousands of copies of a poster to rally the nation. It showed a Union Jack riddled with bullet holes and the legend, ‘Fight to the Death’. The glamorous Argentine news presenter, Magdalena Ruiz Guiñazú, told me of her sorrow at the growing number of dead and injured but said, ‘We are at the point of no return.’ The Junta’s official spokesman Colonel Bernardo Menéndez told me with jutting jaw that sovereignty over the islands ‘No es negociable’ – it is non-negotiable.

The pugnacity of the Argentine Junta surprised many who did not know the recent history of the country. These were men who had been at war in a savage but little reported conflict for more than seven years and already had much blood on their hands. The Generals and senior officers were men who had ordered the torture and often the murder of leftist subversives whom they had kidnapped on the street or dragged from their homes. It was a ‘Dirty War’ against many of their own people, a war that they regarded as a holy struggle against Marxist terrorism and which had extended into brutal suppression of all and every vestige of opposition in Argentina, be it in the form of terrorist gunmen, the leaders of organised labour, or intellectuals, many suspect in the eyes of the military for being Jewish, who advocated an alternative vision for the country’s future. Their victories against these opponents had bred hubris, with some in the Junta’s leadership claiming that they had won the first battle of the Third World War.

The terrorism they had set out to suppress was real enough. It was fuelled by repeated economic crises, with money rendered almost worthless by inflation rates of 500–600%. This gave the terrorists relevance as they evolved into a peculiarly Argentine breed inspired, it was said, by the writings of the Marxist philosopher Frantz Fanon, 16who had delivered his infamous eulogy of terrorism: ‘Violence frees the [individual] from his inferiority complex and makes him fearless and releases his self-respect. Terrorism is an act of growing up.’ The fact that Che Guevara was by origin an Argentine added some glamour to the cause.

In the early 1970s Argentina was plunged into a dark tunnel of violent lawlessness. One of the key landmarks on the road to full-scale repression had been the shocking murder in 1974, when the elected civilian government of Isabel Perón was still in power, of Argentina’s police chief Alberto Villar and his wife Elsa, killed by a bomb hidden aboard the cabin cruiser they used at weekends on the River Plate. Responsibility was claimed by the Montoneros, a left-wing group which proclaimed its allegiance to the now-dead dictator Juan Perón who had mobilised and motivated the working classes, but which was in fact one of the Marxist revolutionary groups surging throughout the Latin American continent, financing itself through highly lucrative acts of kidnapping and extortion. The police chief was known for carrying his own hand grenades on a belt around his waist but they were of little use on this occasion. The powerful explosion lifted the cabin cruiser 30 feet in the air and the bodies of Villar and his wife were found floating in the river.

Operating in parallel and occasional competition was the People’s Revolutionary Army or ERP, a smaller but well-organised Trotskyite group that believed in the propaganda of the deed. At an early stage they had tried to ignite a classic guerrilla war in the rural province of Tucumán in the north-west of the country but found themselves unable to match the Army’s firepower and resorted to urban terrorism. Their attacks on the regime were fewer in number than those of the Montoneros but no less spectacular. They included a well-planned attempt in 1977 to assassinate the Junta’s then leader, 17President Jorge Videla, by placing a powerful remote-controlled bomb in a culvert beneath the runway of the Buenos Aires municipal airport, shortly before an aircraft carrying the President and high-ranking officials took off. The attack only succeeded in damaging the runway. According to the US Defense Intelligence Agency it was a ‘near miss’.4 The same DIA document suggests that together the ERP and the Montoneros carried out well over 1,000 terrorist attacks between 1974 and 1979.

General Jorge Videla had seized power in 1976 in the sixth military coup which Argentina had experienced since 1930. A three-man Junta made up of the heads of the Army, Navy and Air Force installed themselves, promising to restore stability. Videla had already made their intentions clear in a speech to the Conference of American Armies in the Chilean capital of Montevideo the year before. He said: ‘As many people will die in Argentina as is necessary to achieve order.’5

Once in power, Videla had tried to cultivate the image of a humble man who could save the country. But while the new military leaders sought at first to present an apparently reasonable image to the outside world, their security forces stepped up the already brutal campaign against the insurgent threat. Argentina’s still functioning judicial system and conventional police forces were brushed aside in favour of special units using the crude tools of kidnapping, torture and murder. With an ideology embracing fierce nationalism extending at times into fascism and a fervent Catholic faith, the armed forces had always considered themselves the guardians of the Argentine flame. Now they set up what can only be described as a killing machine which dealt with its victims with frightening efficiency, turning them into a legion of the ‘disappeared’. It was a ruthless struggle in which a particularly murderous branch of the security forces was led by a violent career criminal who had earlier carried 18out one of the most spectacular bank robberies in Argentina’s history and who joined the secret police directly from prison. He had been given the power of life and death over the perceived opponents of the Junta and it was he that we would encounter in that square in Buenos Aires.

The progress from anti-terrorist operations to systematic secret slaughter was chronicled by a few brave journalists such as Robert Cox, the Editor of the English-language Buenos Aires Herald (now sadly defunct). Cox, who had settled in and loved Argentina, felt he had to leave the country in 1979 to save his life. The ‘Dirty War’ was also brought to international attention by the growing number of mothers of the young men and women who for whatever reason had been targeted as suspect and vanished into the maw of the machine and who now demonstrated every week, becoming known as the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, after the square in front of the Presidential Palace where they gathered.

The bloodshed was also systematically recorded by operatives of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) reporting to Langley, Virginia from their offices at the US Embassy in Buenos Aires. Hundreds of their reports, including some dealing with our case, have now been released by the US government. The revelations they contain are at the heart of this book and what they make clear is that the CIA was extraordinarily well informed and able to follow the Dirty War on a virtually daily basis as the number of killings steadily mounted.

The many events covered in this secret reporting included ghastly actions by the security forces near the small town of Pilar, a place with which we would soon become acquainted in terrifying circumstances. Pilar had become a macabre landmark, following the discovery soon after the Junta came to power of 30 mangled corpses in a field nearby. Twenty of the victims were male, ten female and 19the bodies had been blown up with dynamite, leaving them almost beyond recognition, but it turned out that the dead were Montonero suspects who had been in police detention. They had apparently been killed by the security forces in reprisal for the murder of retired General Omar Actis, who had been appointed head of the committee organising the forthcoming football World Cup. The CIA stated that the killers, who on this occasion came from ‘operating levels of the Argentine Federal Police’, apparently believed that ‘the public display of the thirty bodies in response to the killing of General Actis would cause the ERP and Montoneros to reassess the advisability of engaging in further terrorist actions in the near future.’6

The CIA report also described the reaction of the new President, General Videla:

President Jorge Videla is annoyed that the bodies were left so prominently displayed and has ordered that this not occur in the future. Videla considers that such a type of situation reflects adversely on the good name of Argentina both within and outside the country. Videla’s objection is not that the thirty people, who were purportedly involved with the Montoneros, were killed, but that the bodies appeared publicly.

As the Dirty War progressed, many other security forces operations remained horrifyingly brazen. The released American documents include a graphic description of the kidnapping of several members of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and two of their supporters, French nuns named Alice Domon and Léonie Duquet.

On Saturday 10th [December 1977] … Mrs Devisente was picked up a block from her house at 8.30 in the morning and thrown 20into a Ford Falcon kicking and screaming. Later in the same morning a French sister accompanied two gentlemen from her house and drove away with them.7

These abductions caused diplomatic protests from both the French government and the Vatican. The Argentine security services then arranged to supply the local press with photographs supposedly showing the two nuns in the hands of Montonero terrorists, although these were widely dismissed as fake. The US Embassy carried out its own investigation and Ambassador Raul Castro finally sent his report to Washington:

A source informs the Embassy that the nuns were abducted by Argentine security agents and at some point were transferred to a prison located in the town of Junín which is about 150 miles west of Buenos Aires.

Embassy also has confidential information obtained through an Argentine government source (protect) that seven bodies were discovered some weeks ago on the Atlantic beach near Mar del Plata. According to this source, the bodies were those of the two nuns and five mothers who disappeared between December 8 and December 10, 1977. Our source confirmed that these individuals were originally sequestered by members of the security forces acting under their broad mandate against terrorists and subversives.8

It was clear that, in spite of the professed Catholicism of the regime and its operatives, religion and even the Vatican’s protests counted for little. In Buenos Aires gunmen targeted St Patrick’s church after a young priest, Father Alfredo Kelly, had preached about the need 21for social justice in Argentina. The armed men broke into the parish house where three priests and two seminarians lived. The gunmen made them kneel as if they were praying and shot them dead. A message was daubed in blood on the wall: ‘This is what happens to those who poison the minds of our youth.’9

Attention focused on Argentina and the horrors taking place there when the country hosted the 1978 football World Cup. But the protests of human-rights groups were brushed aside as the bankrupt nation staged a spectacle which sent soccer-crazy Argentines wild with joy and captivated fans around the world. In front of President Videla and his guest of honour, the former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, whose support had long been of immense value to the Junta, Argentina triumphed in the final against Holland with Mario Kempes, ‘the Matador’, scoring two of Argentina’s three goals. Meanwhile, outside the stadium, the number of victims continued to mount. The Junta finally admitted that 6,500 people were ‘missing’ in its war. Amnesty International put the true figure at that stage at more than 25,000.

By the turn of the decade the military were claiming victor y over the terrorist groups and the numbers of ‘disappearances’ declined. But the Junta made no move to restore democracy. It was determined to hold on to power and knew no other way than the use of its secret police to suppress opposition. Even as General Galtieri sent troops to the Falklands and sought to motivate the nation for confrontation with Britain, teams of ‘dirty warriors’ continued their work at home. We had a glimpse of their operations at a Peronist labour demonstration which, unusually, had been permitted by the regime in order to express support for its ‘Malvinas’ campaign. In a square in the capital, several hundred people waved placards and chanted anti-British slogans as they laid wreaths at 22a monument to workers’ rights. On the fringes of the demonstration we saw a number of men dressed in suits sitting in several of the signature grey Ford Falcon cars. As it ended they got out and with cool self-assurance collected up a selection of the placards and leaflets that had been distributed among the crowd and wrote down the names of people who had signed the commemorative wreaths. Perhaps unwisely, we filmed them going about their business and then a short time later went to the scene of the latest known ‘disappearance’ where, in a rundown street on the outskirts of the city, a young leftist called Anna Maria, pregnant with her soon-to-be-born child, had been kidnapped a few weeks before. Eight days after the kidnapping her body had been found nearby with two bullet wounds, one in the head, the other in the stomach. We filmed the location unaware as we did so that, according to the now-released CIA documents, we ourselves were under surveillance by the secret police.

We had already met the man who was officially in command of much of Argentina’s security apparatus, the Interior Minister, General Alfredo Saint-Jean. Unlike the famously bad-tempered Foreign Minister the grey-haired Saint-Jean was calm, almost avuncular, as he welcomed us in front of a large oil painting which adorned the wall of his office. A broad panorama, it showed uniformed sabre-wielding Argentine cavalry riding down fleeing Amerindians on one of the country’s vast open plains. The Minister explained with some satisfaction how the indigenous populations had been dealt with – leading, he claimed, to the establishment of a coherent European-based society without ethnic discord. He then turned to the crisis with Britain.

‘We are a peace-loving nation,’ he told me without a hint of irony, ‘But don’t misunderstand me. Argentinians will not renounce 23their rights to the islands. Argentina will negotiate but only as far as dignity will allow.’

Off-camera the Minister responded to our concerns about our own safety. He assured us that we were welcome in Argentina and that no one would interfere with our work. ‘If you have any difficulties, telephone me here at the Ministry,’ he said, writing down his direct number on a piece of paper.

But at that moment it was the Minister’s repeated use of the word dignity that resonated and seemed a key to understanding the dictatorship’s behaviour in this crisis.

With Argentinian troops preparing to defend their positions on the islands against what now seemed to be an inevitable British assault, defence of the nation’s dignity depended heavily on the pilots of the country’s motley collection of combat aircraft, organised in Air Force and Naval squadrons who alone could now challenge Britain’s supremacy at sea. These were the men that the Junta celebrated as its noblest fighters and they were to show the world another side of the uniquely contradictory Argentinian character, combining both the potential for savage brutality with a belief in courage and chivalry. Untried in aerial combat, they were to display bravery and skill that even the British task force commander, Admiral Sir John ‘Sandy’ Woodward, would acknowledge. ‘We felt a great admiration for what they did,’ he would later say.

On May 12th, almost 500 miles from the capital of the Falklands, Port Stanley, at the Argentine Air Force base at Río Gallegos near the windswept southern tip of the country, where bleak open spaces meet treeless horizons under grey leaden skies, ground crews were preparing eight jets for an attack on the British fleet. The planes were American-made Douglas A-4 Skyhawks, a design from the 1950s which had played an important role in the Vietnam War and 24in the Middle East, but was now becoming dated. Unable to carry any of Argentina’s small stock of Exocet missiles, each Skyhawk was loaded with 500lb or 1,000lb unguided ‘iron’ bombs, Second World War vintage weapons which had to be released at close range and would depend for success on the pilot’s bravery, skill and luck. Some of the aircraft were also in poor condition with their ejector seats known to be unreliable.

First Lieutenant Fausto Gavazzi, recently married, was one of eight pilots suiting up for what some of his fellow officers believed would prove to be a suicide mission. In a chilling dress rehearsal hastily arranged as the British task force assembled, Gavazzi’s squadron had taken part in mock attacks on one of the two Type 42 destroyers that Britain had sold to the Argentine Navy in the 1970s. These ships, designed for an air-defence role, had recently been refitted with Seacat anti-aircraft missiles similar to those carried by the Royal Navy, and a series of low-level simulated bomb runs had shown the Skyhawks being repeatedly shot down by the system. However, in the attacks on May 1st Argentinian Dagger aircraft, originally Mirage V jets designed in France and assembled and sold to Argentina by Israel, had carried out low-level attacks on British ships. The bombs had missed and only inflicted limited damage and one of the Daggers had been shot down by a Harrier. However, the fact that they had got through to their targets had encouraged Argentine commanders to order major attacks by the Skyhawk pilots.

On May 12th the plan was simple in conception but difficult and perilous to execute. After take-off the heavily laden Skyhawks would extend their range by refuelling from one of Argentina’s two US-built KC-130 airborne tankers and then fly at sea-skimming level to find the British fleet. Though the weather was fine the pilots were to some extent flying in the dark. Without reliable long-range aerial 25reconnaissance they had only a general idea of where the British warships were. Radio messages from their troops in the Falklands, reporting that the British were now shelling them with their naval guns, suggested that there were ships quite close to the shore. The mission was to release their bombs at the closest range they could manage and then speed away at the lowest possible altitude before British missiles and guns could lock on and destroy them.

On that day the word dignidad – dignity – was undoubtedly a powerful motivator for the men flying the Skyhawks but for me, lying in the footwell of the Ford Falcon with a cloth over my eyes and a gun to my head, I must admit that it was not the most urgent thought in my mind.26

Notes

1. Sir John Nott autobiography, Here Today, Gone Tomorrow, Politicos Publishing, 2002.

2.The British Invasion of the River Plate 1806–1807, by Ben Hughes, Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2013.

3.The Fight for the Malvinas: Argentine Forces in the Falklands War, by Martin Middlebrook, Viking, 1989.

4. US Defense Intelligence Agency report on ‘International Terrorism’ dated March 30th, 1980.

5.The Guardian, obituary, May 7th, 2013.

6. CIA intelligence information cable, August 25th, 1976.

7. Transcript of voice recording sent to US State Department by Embassy Human Rights Officer Allen ‘Tex’ Harris, May 31st, 1978 (released 2017). The name of the lady who was kidnapped and subsequently ‘disappeared’ was, in fact, Mrs De Vicenti, the error apparently being caused by faulty transcription of ‘Tex’ Harris’s recorded voice message to Washington.

8. Telegram from US Ambassador Raul Castro to US State Department, March 30th, 1978 (released 2002).

9.Dossier Secreto, by Martin Edwin Andersen, Westview Press Inc., p. 187.

CHAPTER 3

End of the Road

Ihad almost got used to the steady motion of the vehicle and my cramped position in it when it came to a sudden halt. We were in some sort of lay-by and to my surprise Trefor, our sound recordist, was pushed into the car. We were made to sit next to each other on the back seat and told to be silent and keep our eyes closed. We drove on into the countryside for what seemed an eternity. Then on what appeared to be a dirt track the car stopped again. Brusquely we were shoved out and saw other cars with more gunmen, who were guarding Ted, our cameraman. Of Norman there was no sign. Disconcertingly, Ted was taking off his clothes.

The sinister convoy had halted on the corner of a vast field stretching away into the distance. I saw the courage which my two colleagues were showing and tried to take heart from it.

The three of us could say no more than a word of recognition before being told to shut up. Trefor and I were instructed in broken English to turn away from the gunmen, empty our pockets of our possessions and take off our clothes – though, strangely, not our underpants. I was asked some questions about the contents of my notebook but I don’t know if I gave any coherent replies. The three 28of us stood cold, almost naked and virtually numb with fear while the commander’s radio crackled sporadically behind us. I was in no condition to understand fully what our kidnappers were saying or doing but it seemed that they intended to kill us. In the words of Ted Adcock: ‘They brought out a rifle and they pointed at it, and they said to walk down the road. One had to turn one’s back on the rifle and walk away from it and I guess that’s quite scary. It was tough.’

We walked slowly and silently, three abreast, away from the gunmen. Trefor was next to me and I found myself holding his hand. Behind us I heard the unmistakable double-click from the loading mechanism of the rifle, a sound that I had heard often enough in Vietnam. There was no way to run and nowhere to hide. At any second the bullets would hit us and the light of life would go out. In a recent conversation to assist in the preparation of this book, Ted kindly shared his memories with me. ‘I was praying that they would shoot me first,’ he now says. ‘That way I wouldn’t know it was happening.’

Then there was a sound. It was not the crash of a rifle or the crack of a pistol. It was the sputtering of a car engine starting up, then another, then a third. Wheels crunched on soil but we stood still, looking away, not daring to turn round. When we did, we were alone.

Instead of lying in pools of blood after the sort of execution that had taken place so often in Argentina, we were standing near-naked in a field, in the middle of a country at war with Britain.

As Trefor put it in his characteristically understated fashion: ‘There were a few sighs of relief when they drove away.’

I think all three of us felt the same elation of survival. As emotion surged we grinned and laughed and felt what can only be described as joy.29

Those moments have come back to me many times since: the sheer terror, the happiness of survival and the ultimate absurdity of our situation.

In a nearby unattended farm building, we found empty fertiliser sacks to wrap around our waists, but these did little to improve our appearance and our plight seemed to frighten the farmers who drove up in a pick-up truck not long afterwards.

One, however, seemed more amused than concerned. ‘Today my birthday,’ he announced in surprisingly good English, ‘I didn’t think I get three naked Englishmen.’ He drove us to the nearest town which was called Pilar, though at the time the name meant nothing to us, and took us first to an Army base where the troops made it clear that they wanted nothing to do with us. The helpful farmer then dropped us at the local police station. There, still uncomfortably half-naked, I sat in a plastic chair in front of the young commander and attempted to explain how we had arrived in his office. It was evident that insofar as he understood my fragmentary Spanish he didn’t believe a word of it.

The police commander developed his own theory: Argentina was at war with Britain. Plainly we were from the British military and were part of a Special Forces operation that had gone wrong. Our nakedness, though puzzling, was doubtless just another British ruse. Our physical condition was surprisingly poor for members of a commando unit – with the best will in the world none of our team could be said to have resembled an elite paratrooper – but perhaps Britain was scraping the bottom of the barrel.

‘Periodistas’ (journalists), I told him repeatedly, ‘secuestro’ (kidnap). I begged him to lift the telephone which sat on his desk in front of him and call the Interior Minister, General Alfredo Saint-Jean, who would vouch for us. After what seemed an eternity of futile 30exchanges the commander dialled a number, said something to whomever answered the phone and sat back with a disbelieving expression on his face.

Twice in my career I saw someone salute a telephone. The other occasion was in Soviet-era Moscow where in the middle of an interview with a senior official at the Ministry of Defence a large old-fashioned telephone without a dial suddenly rang on his desk. This was the fabled vertushka, through which instructions to the upper echelons were issued on a downward-only basis and the caller in this case could only be the Minister of Defence himself. The official stood, took the receiver in his left hand and, disregarding our presence, saluted with his right while listening intently to what was said.

On this occasion in the small town of Pilar, the police commander’s behaviour indicated that he had got through to the man at the top. He suddenly stood to attention bolt upright, saluting, and said repeatedly, ‘Yes, my General. Yes, my General. It will be done.’ It turned out that the Interior Minister was already aware of our disappearance, having been alerted by our producer Norman Fenton who, aided by his remarkable sixth sense, which we had frequently discussed in the past, had evaded the kidnapping and managed to contact the Minister, who had apparently reacted to the news with fury and now issued his instructions. In the Pilar police station officers who had been sullen suddenly fell over themselves to make us more comfortable. Military-style fatigues were produced to cover our nakedness and hot drinks were prepared as the atmosphere turned to bonhomie.

‘The Minister is sending his own car,’ the Commander assured me, ‘It will be here soon.’

A very large limousine accompanied by six motorcycle outriders duly arrived an hour later and we began the journey back to Buenos 31Aires in splendid fashion. What we did not know as we reclined in the comfortable vehicle driving us back through the fields around Pilar was that this was an infamous location, where the security services continued to leave numbers of their victims in the Dirty War. It seemed that the convenience of proximity to the capital and speedy access down the Pan-American Highway made this a practical dumping ground – something our kidnappers had seemed to know well. Our case was unusual in that we were still alive.

In our reports from Buenos Aires we had already described the fears spreading in the sizeable British community in Argentina as the war turned hot. David Huntley, married to an Argentine and father of two children, was not one of the wealthy Anglo elite but a hotel worker earning the equivalent of £40 a week. He told me of whispered insults from fellow workers and of his fears every time he boarded a bus. He said that he and his family would leave the country if they could, but lacked the means to do so.

David’s fears were not irrational. Just how dangerous and unpredictable the situation in Buenos Aires had become, and how lucky we were on May 12th, has become clear in previously secret CIA documents now released by the US government and which I have examined in detail. Until their disclosure, there were few clues as to what was taking place in the complex world of Argentina’s spies and executioners as the conflict with Britain intensified.

What we now know from the American documents is how Argentina’s secret world was organised and some of the murderous plans it had drawn up in the event of full-scale war with Britain. The CIA analysts identified the key department responsible for black operations as the 601st Intelligence Battalion of the Argentine Army. This special unit, whose activities were shrouded in secrecy and widespread fear, had been for years at the centre of the Dirty War, 32collecting information on opposition groups and employing death squads to eliminate them. The battalion had already been repeatedly highlighted in secret American reports as a key component in the Junta’s torture and killing machine. A diagram of its structure drawn up by the CIA1