29,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crown House Publishing

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

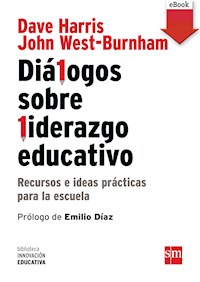

Following on from their bestselling title Leadership Dialogues, Dave Harris and John West-Burnham's Leadership Dialogues II: Leadership in times of change examines eight more themes crucial to the effective education of our young people in schools. We are living in times in which school leaders are looking for both simple answers and detailed instructions to help them progress to their goals. But in a period of rapid change, like the one we are in now (at least for the foreseeable future), there is no step-by-step guide, there is no instruction manual only strong tools to support leadership teams on their journey. Leadership Dialogues II is not a book containing all the answers; rather it is a book containing many of the questions that will help school leaders work with their colleagues to find the answers for their own schools within the communities in which they work. Harris and West-Burnham believe that the best people to interrogate the problems and find the answers are those people working in, leading and governing these schools every day, and so they have compiled this helpful resource to promote more constructive dialogue and debate which will result in the generation of feasible solutions specific to their own schools. Each of the eight themes in Leadership Dialogues II is of contemporary relevance to 21st century education and is split into five sections, each containing an outline on why this is an important topic, some key quotes to engage your thinking, a 10 minute discussion to provoke debate, some questions for your team to consider and to help frame the dialogue's outcomes downloadable, printable resources for each section. The resources are often in tabular form and relate to the material, which means they can be used with little extra preparation, and are all available for download in PDF and Word formats for ease of circulation. The only thing you have to do is think, discuss and then act. The eight themes explored are: securing equity and engagement; clarifying the purpose of education; middle leadership the engine room of the school; managing resources; learning and technology; education beyond the school; alternative staffing models; and developing evidence based practice. Suitable for school leadership teams in any setting.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Praise for Leadership Dialogues II

Our leadership teams have never needed more training in their roles as they do now during these challenging times. And as the original Leadership Dialogues has proven to be such a powerful tool for leaders, I believe Leadership Dialogues II will be another important step in the process of developing and improving their skills.

Harris and West-Burnham offer a serious reflection on leadership with very interesting resources which enable the reflourishing of previous thinking on the topic, and they expertly tackle a wide variety of key points – from the importance of useful meetings to the real purpose of education – from the most particular points up to the most general and crucial ones.

Juan Carlos García, Pedagogical, Pastoral and Innovation Department, Escuelas Católicas de Madrid

At a time when school leadership is pressurised into consisting of leading a school to a decent set of exam results and an inspection that keeps ‘them’ off your back for a few more years, Leadership Dialogues II puts the heart, the soul, the integrity and the moral purpose back into its core. It combines common sense, wisdom and research based practice to great effect in imbuing school leaders with the tools, knowledge and bravery to be the leaders that any education system truly deserves.

Ian Gilbert, founder, Independent Thinking

In the same way that the original Leadership Dialogues became an indispensable manual for reviewing the fundamental aspects of school leadership, Leadership Dialogues II takes leadership teams on similar journeys into deeper and currently relevant areas for review; from securing equity and engagement to analysing the use of research in education, via a debate on the purpose of education. Such is the quality and depth of content and the ease of reading, leadership development is unavoidable.

Don’t expect that this book will give you all the answers, however – it won’t. What it will do is stimulate and structure thinking, and challenge leadership teams to find the answers from within their own schools. This book is the catalyst, not the solution.

Paul Bannister, Junior School Head Teacher, Jerudong International School

From cover to cover Leadership Dialogues II provides a rich array of highly engaging themes as well as practical tools; yet it serves no straight answers. It is a gem of a read, a book many school leaders have always hoped someone would write just for them in order to boost their leadership capacity, help explore sensitive topics through asking relevant questions, back them up when empowering staff and stakeholders to generate optimum solutions for students, schools and communities, and provide a shot of inspiration to build a society centred around improved well-being.

Janja Zupančič, Head Teacher, Louis Adamic Grosuplje Primary School, Slovenia

To address today’s issues, and those beyond the horizon, we need support in finding solutions, and these are best constructed through well-formed dialogue – which begins by interrogating good practice before moving on to building consensus. This is the distinct aim of Dave Harris and John West-Burnham’s Leadership Dialogues II.

So whether you are looking at challenges as diverse as developing middle leadership, considering alternative staffing models or raising the achievement of disadvantaged pupils, this book will provide evidence and research to consider, questions to help form discussions and, finally, guidance to help you act to make your school or trust as effective as possible.

Paul K. Ainsworth, academy adviser for a system leader multi-academy trust and author of Middle Leadership and Get That Teaching Job!

Leadership Dialogues II has the moral imperative of education at its heart: to create happy, confident and successful learners. School leaders reading this book will be encouraged to focus on the key questions they have about their own settings and to then take action based on a holistic view of learning and learners, collective responsibility and shared mental models. Educational wisdom, insightful dialogue and challenge are balanced with simple yet extremely powerful reflective tools. Leadership Dialogues II is a flexible resource that will galvanise leadership of positive change in schools based upon the learning needs of children and young people.

Jan Gimbert, education adviser and trainer

Leadership Dialogues was always my ‘go to’ book when planning for more strategic work towards school improvement. This follow-up picks up from where the first left off, adding sections on topics such as purpose, engagement and developing evidence based practice.

Some of the chapters are perennial favourites when it comes to educational thinking; however, the difference with this is the fresh perspectives and divergent thinking it provides. I particularly like the theme of doing things differently – which other educational book would give you the idea of looking at your school as if it were a car, as Harris and West-Burnham have?

Essential reading for those of us lucky enough to be leading education.

Keith Winstanley, Head Teacher, Castle Rushen High School

Relevant, practical and packed full of great resources, Leadership Dialogues II is essential reading for leaders at all levels in schools. It offers both theory and practice, which is great for busy leaders, and provides a really good platform for reflection, thinking and dialogue. The authors really understand the complexities of leadership, and inspire possible solutions and ways forward in a thoughtful but practical way. I highly recommend this book.

Stephen Logan, Deputy Head Teacher, Malet Lambert School

Asking some of the biggest questions of our time, the hugely influential and respected Dave Harris and John West-Burnham provide an external perspective and a range of support materials to aid schools’ internal constructive dialogues and decision making. Their think pieces and diagnostic review tools aim to help school leaders make value led, deep rooted, wise decisions for the pupils and staff they lead.

Far ranging and simply brilliant, Leadership Dialogues II is a ‘group reader’ that all those working in schools should use and engage with.

Stephen Tierney, CEO, Blessed Edward Bamber Catholic Multi Academy Trust, blogger (leadinglearner.me) and author of Liminal Leadership

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the many individuals who have contacted us to tell us how useful they found the original Leadership Dialogues. We know of schools who use it as a regular part of the leadership meetings and others who have developed teacher leadership training programmes around it. This was always our aim – not to provide answers, but to promote dialogue.

In a time when many still judge education using simplistic, data-driven, archaic techniques, it is heartening to meet so many people whose only focus is to help young people become happy, confident and successful learners.

To those brave, passionate and dedicated leaders – thank you.

Keep making a difference!

Contents

How to use the book

This is not a book containing all the answers. It is a book containing many of the questions that will help you work with your colleagues to find the answers for your own school for the community in which you work.

We are living in times in which people are looking for both simple answers and detailed instructions to help them progress to their goals. But in a period of rapid change, like the one we are in now (at least for the foreseeable future), there is no step-by-step guide, there is no instruction manual – only strong tools to support you on your journey.

There will be similar themes underlying the problems faced by schools across the world, but the precise issues tend to be very specific to each school. The best people to interrogate the problems and find the answers are those of you working in, leading and governing these schools every day.

We have produced a book that we believe you will find helpful as a means of promoting constructive dialogue and debate, which will result in the generation of feasible solutions for your school.

For each of the eight themes in this book we have assembled five sections, each of which contains an outline on why this is an important topic, some key quotes to engage your thinking, a 10 minute discussion to provoke debate, some questions for your team to consider and, to help frame the dialogue’s outcomes, downloadable resources for each section. The resources are often in tabular form and relate to the material, which means you can use them with little extra preparation. The only thing you have to do is:

To think and then discuss and then act.

The eight themes explored in this book are:

1 Securing equity and engagement

2 Clarifying the purpose of education

3 Middle leadership – the engine room of the school

4 Managing resources

5 Learning and technology

6 Education beyond the school

7 Alternative staffing models

8 Developing evidence based practice

These complement those explored in the first Leadership Dialogues book:

A Effective leadership

B Thinking strategically

C Leading innovation and change

D Leading teaching and learning

E Leading and managing resources

F Leading people

G Collaboration

H Engaging with students, parents and community

Schools/groups of schools have found that book to be a useful backbone for their own staff development courses to support both established and developing leaders. In some cases, materials have been co-designed with the authors and then most of the sessions delivered by staff from within the schools. The key point is to make sure that the materials chosen are relevant to the situations being faced by the learners and suited to the situation of the school.

We believe the answers for school improvement usually lie within many of the people already in the institution. Leadership is about causing those changes to happen. Our book is intended to add an outside perspective, a list of ideas to consider and questions to ask. Not to make schools develop in the way we think, but to help schools develop in the best way for the future of their pupils.

Do not hesitate to contact either of the authors to discuss ways to adapt the materials in both books to suit your own specific demands.

Introduction

Leadership learning through dialogue

If learning and leadership are both seen as primarily social processes, then dialogue is the medium and the message. Leaders work through various permutations of social interaction in order to engage as leaders. They can be highly effective and make a significant impact to the extent that they have the skills and behaviours appropriate to dialogue.

High quality dialogue is fundamental to almost every aspect of leadership; not only does it enhance the potential impact of leaders, it also serves to model appropriate relationships to leaders, staff and pupils.

“The general feature of human life that I want to evoke is its fundamentally dialogical character. We become full human agents, capable of understanding ourselves, and hence of defining an identity throughout acquisition of rich human languages of expression. […] No one acquires the languages needed for self-definition on their own. We are introduced to them through exchanges with others who matter to us.

(Taylor, 1991: 33; original emphasis)”

People grow personally through their pivotal relationships, and also grow professionally through such relationships. However, the number of people that we engage with has a significant impact on the integrity and potential of these relationships – effective dialogue depends on quality and quantity. The potential significance and impact of dialogue is in inverse proportion to the number of people involved. Thus coaching, normally a one-to-one relationship, is probably the most significant and potentially successful strategy to support learning, personal change and growth. Five to seven participants seems to be the optimum number and after that the potential impact of dialogue is possibly diluted. In his study of human and animal interaction, Robin Dunbar argues that we live in what he calls ‘circles of intimacy’ that determine the regularity and depth of our relationships. The most significant circle is the innermost – usually a maximum of five people.

“It seems that each of [our] circles of acquaintanceship maps quite neatly onto two aspects of how we relate to our friends. One is the frequency with which we contact them […] But it also seems to coincide with the sense of intimacy we feel: we have the most intense relationships with the inner five.

(Dunbar, 2010: 33)”

This is a dimension of leadership that has not received the level of attention it needs or deserves. Leadership is usually at its most effective when it is relational rather than positional. One of the great strengths of dialogue is the potential it has to enhance relationships and secure engagement – an obvious example is the influence of coaches in sport.

Dialogue in leadership is a key resource to support a range of activities and desired outcomes, such as:

→ Developing shared understanding.

→ Using analytical techniques to identify problems and generate possible solutions.

→ Fostering a common language and shared vocabulary.

→ Enhancing the quality of decision making.

→ Working to build consensus.

→ Exposing fallacious and illogical arguments.

→ Boosting team effectiveness and productivity.

→ Questioning and challenging different perspectives.

Successful dialogue is a complex blend of art and science in that its success depends on elusive qualities such as trust and empathy. At the same time there are very clear protocols that inform the quality of outcome and process. A taxonomy of successful dialogue will include most of the following elements:

→ Mutual trust rooted in shared respect.

→ Empathy based on sensitivity to the needs of others.

→ Interdependent and collaborative working.

→ Commitment and engagement.

→ Appropriate questioning and challenge.

→ Feedback and reciprocity.

→ Recognition and reinforcement.

→ Humility and recognition of alternative perspectives.

→ Laughter.

→ Review to support improvement and consolidate success.

Above all, dialogue is a strategy to support personal learning and development through interactive and interdependent working such as lesson study. In this respect it is akin to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978) – that is, learning potential is significantly enhanced through social interaction. In many ways it resembles the sort of learning that is found in action learning and joint practice development. The key to successful dialogue lies primarily in the quality of the questions asked and the challenges presented, and to the rigour of the dialectical process that seeks greater and greater clarity.

Many leadership teams have used the first Leadership Dialogues book as the basis for dialogue as part of their regular meeting cycle, and we would strongly endorse this use of leadership team time. However, it is worth stressing that while business meetings and leadership dialogues have much in common, successful team dialogue requires some specific elements to be in place, in particular:

→ A culture of challenge, analysis and reasoning.

→ Openness and inclusion.

→ Use of evidence where appropriate.

→ Recognition of the knowledge base available in the literature.

→ Translating principle into practice.

→ Taking action and working through practical projects.

→ Reviewing and reflecting on task and process.

Of course, it is the conversational dimension of dialogue that is the most significant element. However, it would be wrong to ignore the importance of review in terms of the focus of the conversation and the quality of the different aspects of the dialogic process. Essentially, the how is as least as important as the what. If senior leaders become confident and skilled at working through dialogue, then this can only be of benefit to their work with middle leaders and teachers – and so with pupils.

Securing equity and engagement

A The education of vulnerable and disadvantaged pupils

Why is this an important topic for conversation?

One of the great challenges for those involved in any aspect of public service is to secure equality and equity, notably for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged. In essence, most education systems in the developed world have achieved equality – in that every child goes to school. However, it is true of many systems that not every child goes to a good school or that for many children the education system actually exacerbates their disadvantage by not providing appropriate compensatory interventions. Equity is essentially about fairness and social justice. Securing equity can be seen as the most fundamental component of school leadership and governance, and yet it remains elusive and problematic.

Key quotes for the section

“There is a growing body of evidence that shows that the highest-performing education systems are those that combine equity and quality. Equity in education is achieved when personal or social circumstances, such as gender, ethnic origin or family background, do not hinder achieving educational potential (fairness) and all individuals reach at least a basic minimum level of skills (inclusion).

(OECD, 2015: 31)”

“[E]quity is not the same as equal opportunity. When practiced in the context of education, equity is focused on outcomes and results and is rooted in the recognition that because children have different needs and come from different circumstances, we cannot treat them all the same.

(Noguera, 2008: xxvii)”

Section discussion

Securing equity in education is both a moral imperative and a highly practical approach to governance, leadership and management. In many ways it can be seen as a test of the ability of leaders to translate policy into practice. It might be argued that the priority of some education systems has been quality, in terms of outcomes measured as academic excellence. Only in recent years has equity been seen as a significant factor.

In broad terms this is all about closing the gap. This is one of the crucial challenges for schools and government, and one that in England and other similar education systems remains stubbornly elusive. In England, the gap is usually understood as the difference in performance between pupils who are entitled to free school meals (FSM) and those who are not. In one of his final speeches as Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools, Sir Michael Wilshaw made the following depressing observation:

The attainment gap between FSM and non-FSM secondary students hasn’t budged in a decade. It was 28 percentage points 10 years ago and it is still 28 percentage points today. Thousands of poor children who are in the top 10% nationally at age 11 do not make it into the top 25% five years later. (Wilshaw, 2016)

A key strategy for closing this gap has been the pupil premium, but evidence about its use seems to suggest that schools have not always followed the evidence available from the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) Toolkit on Teaching and Learning.1 Research has shown that ‘Early intervention schemes, reducing class sizes, more one-to-one tuition and additional teaching assistants in the school were the most frequently cited priorities for the Pupil Premium’.2 This is in spite of the fact that these approaches were rated as being less effective in terms of cost and impact.

Clearly, schools believe they are responding to research – in fact, ‘More than half (52%) of the teachers said their school uses past experience of what works to decide which approaches and programmes to adopt to improve pupils’ learning. Just over a third (36%) said their school looks at research evidence on the impact of different approaches and programmes’ (ibid.).

Drawing on the NFER review of the strategies to support the education of disadvantaged pupils (Cunningham and Lewis, 2012) and the EEF toolkit, the following themes emerge as a basis for moving towards more equitable school based policies and interventions (Macleod et al., 2015):

1 A culture of high expectations and aspirations that apply to every aspect of the school’s life and every member of the school community. In essence, the idea of the growth mindset applies to every dimension of school life – moving from ‘I can’t’ to ‘I can’t yet’.

2 Securing engagement (see Section 1B).

3 Working towards consistently high teaching standards for all students – deploying the most effective teachers to the most disadvantaged groups.

4 Professional practice is evidence based in terms of accessing the research evidence to identify effective practice; developing a culture of professional enquiry across the school to review and improve practice; and ensuring that provision is informed by accurate and meaningful data.

5 Working towards personalised approaches for every student in order to optimise the relevance of their curriculum experience and the appropriateness of teaching and learning strategies. Crucially, providing choices that enhance the potential for engagement.

6 Leadership which secures that all of the above is consistent and equitable.

A crucial dimension of the leadership culture that is necessary to secure equity is a focus on middle leadership and, in particular, a strong sense of personal and collective accountability for the success of every individual. Middle leaders are essential to this process. A key theme of senior leadership and governance has to be the development of this culture across the school and the embedding of such accountability in the work of school governors, the leadership priorities of senior staff and the clarification of focus for middle leaders.

Equally significant is the development of a culture that is responsive to the actual involvement of pupils rather than relying only on adults’ perceptions. This requires the detailed monitoring of pupil voice and the active involvement of pupils in the critical decisions that inform and influence their educational experiences.

With this in mind, three resources accompany this section. Resource 1A(i) enables you to obtain a real view of how your staff feel the key areas identified in the NFER review are progressing in your school. Resource 1A(ii) does the same for pupils. Resource 1A(iii) can be used to collate the results and focus priorities for the school.

Key questions

What do your school’s aims or value statement say about fairness, equity and securing parity of esteem for all pupils?

When did you last audit the extent to which your principles on equity are reflected in practice?

What are the perceptions of your pupils and their parents?

To what extent are your strategies to close the gap (and spend pupil premium funding) based on reliable evidence?

Resources (Download)

B Securing inclusion

Why is this an important topic for conversation?

Engagement is what makes the difference in terms of pupils getting the very best from their time at school and then realising their potential. Thinking about engagement in a holistic way, rather than in a piecemeal way, creates the possibility of understanding the factors that determine the extent to which pupils are fully committed to their own learning and are active members of the school community. In other words, inclusion!

Key quotes for the section

“The residents [of Sardinia] aren’t blessed with extraordinary long lives because they drink the local red wine or eat plum tomatoes from their gardens … ongoing face-to-face social contact with people who know and care about them matters more.

(Pinker, 2015: 60)”

“Of 64 studies of co-operative learning methods that provided group rewards based on the sum of members’ individual learning, fifty (78%) found significantly positive effects on achievement and none found negative effects. Co-operative learning offers a proven practical means of creating exciting social and engaging classroom environments.

(Slavin, 2010: 170)”

Section discussion

Many of the tests of school effectiveness (e.g. Ofsted in England) take the various components of engagement as crucial evidence of effective leadership and management. For example:

Inspectors must spend as much time as possible gathering evidence about the quality of teaching, learning and assessment in lessons and other learning activities, to collect a range of evidence about the typicality of teaching, learning and assessment in the school. Inspectors will scrutinise pupils’ work, talk to pupils about their work, gauging both their understanding and their engagementin learning, and obtain pupils’ perceptions of the typical quality of teaching in a range of subjects. (Ofsted, 2016: 20)

The key issue for this section is that engagement is essentially about relationships: the individual’s relationship with school, with teachers and their peers and, crucially, their personal sense of efficacy, value and the extent to which they view their future with hope and optimism.

Pupil engagement is the outcome of the interaction of a number of complex variables. Get the factors in the figure below as positives and engagement is almost certain; however, if they are negatives then it is very difficult to envisage situations where engagement will exist. We all know of the student who will only engage with one teacher or other adult in the school or who will truant from specific lessons but be in school without fail for others.

The Cambridge Primary Review define engagement as: ‘To secure children’s active, willing and enthusiastic engagement in their learning’ (Alexander and Armstrong, 2010: 197). The components of such engagement are shown below.

Intrinsic motivation

Intrinsic motivation is found in those students who have made a personal psychological commitment to their work. They are working because they want to rather than because they have to. They take pride in their work, often exceed expectations in terms of work and performance, and persist even when faced with challenges or obstacles. They value their involvement in the learning process for its own sake and welcome participation with others – their engagement is often infectious. According to Carol Dweck (2006), some people believe their success is based on innate ability; these individuals are said to have a ‘fixed’ theory of intelligence (fixed mindset). Others, who believe their success is based on having the opposite mindset, which involves hard work, learning, training and doggedness, are said to have a ‘growth’ or an ‘incremental’ theory of intelligence (growth mindset). Intrinsic motivation is also about self-efficacy, self-belief and a positive disposition that is essentially optimistic about personal potential.

Relationships

Relationships with other pupils and staff are based on high levels of mutual respect, trust and courtesy. Pupils feel safe and confident with each other and are supported in adopting strategies to develop emotional literacy and mature interactions.

Skills development

Challenge only engages to the extent that learners have the skills commensurate with the challenge, otherwise they are either bored or intimidated. Cognitive skills development of attributes such as analysing and synthesising, explaining and justifying, demonstrating causality and constructing a logical argument all have the potential to increase confidence, personal efficacy and therefore engagement.

Coaching and mentoring

Coaching is often seen as a panacea for most issues of engagement and development, and it is generally credited with being one of the most potent learning strategies. For feedback to make an impact on an individual’s learning, potential achievement and possible success, the teacher/facilitator/coach has to focus on developing a growth mindset and fostering a relationship based on a balance of challenge and skills development, underpinned by high trust and a shared commitment to improvement.

Parental aspirations

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the importance of values and attitudes in determining pupil engagement. The implicit and explicit attitudes towards school and education in general are a crucial factor, especially in the early and primary years. Quite apart from parental influences on literacy and cognitive development, it is parental attitudes that influence a child’s potential engagement.

Collaborative learning

Learning is a social process. While there is much that we can learn on our own in most situations, collaborative learning is often more effective in terms of understanding and application.

Relaxed alertness is the optimal state of mind for meaningful learning. People in a state of relaxed alertness experience low threat and high challenge. Essentially the learner is both relaxed and to some extent excited or emotionally engaged at the same time. This is the foundation for taking risks in thinking, questioning and experimenting, all of which are essential. In this state the learner feels competent and confident and has a sense of meaning and purpose. (Caine et al., 2009: 21; original emphasis).

Challenge

Problem solving is the basis of all effective learning and we are at our most effective as learners when faced with a challenge, a problem to solve or an enquiry to follow. One way of understanding human development is to see it in terms of an increasing capacity to solve problems collaboratively. Challenge based approaches are the basis of most leisure activities and an essential component of the cognitive development of young people. Challenge in learning is a key element in securing engagement.