Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

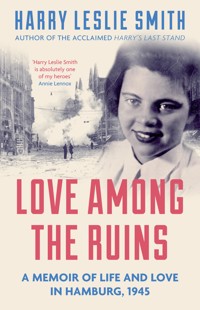

'[Harry Leslie Smith] is absolutely one of my heroes. Everyone should read this and be humbled.' Annie Lennox 'A deep love of humanity is what animates Smith. He is a hero of our times.' Newsweek 'His straight-from-the-heart delivery makes these events seem as clear and immediate as if they happened yesterday' Morning Star At 22, the war is over for RAF serviceman Harry Leslie Smith – the now 92-year-old activist and author of the acclaimed Harry's Last Stand – but the battle for love and hope rages on. Stationed in occupied Hamburg, a city physically and emotionally ripped apart by Allied bombing, and determined to escape the grinding poverty of his Yorkshire youth, Harry unexpectedly finds a reason to stay: a young German woman by the name of Friede. As their love develops, they must face both German suspicion and British disapproval of relations with 'the enemy'. Harry's ardent, straight-from-the-heart memoir brings to life a city reduced to rubble, populated with refugees, black marketeers, corrupt businessmen and cynical soldiers. Love Among Ruins: A memoir of life and love in Hamburg is a unique snapshot of a terrible period in Europe's history, and a passionate love letter to a city, to a woman, and to life itself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 362

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LOVE AMONG THE RUINS

LOVE AMONG THE RUINS

A MEMOIR OF LIFE AND LOVE IN HAMBURG, 1945

HARRY LESLIE SMITH

Published in the UK in 2015 by Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre, 39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected] www.iconbooks.com

Originally published in 2012 under the title Hamburg 1947: A Place for the Heart to Kip by Barley Hole Press, Belleville, Ontario

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House, 74–77 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road, Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India, 7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City, Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada by Publishers Group Canada, 76 Stafford Street, Unit 300, Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed to the trade in the USA by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101, Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

ISBN: 978-178578-000-4

Text copyright © 2012, 2015 Harry Leslie Smith

The author has asserted his moral rights

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher

Typeset in Monotype Bell by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Contents

About the author

Acknowledgements

To the reader

1 1945: The conditions of surrender

2 Staying on

3 A summer in the ruins of Troy

4 A coffee house on the banks of ruin

5 The city in the shadow of the Michel

6 Behind the screen door

7 The bargain between a mother and an uncle

8 Altona gypsies hide their secrets

9 Life observed from binoculars

10 The birthday party

11 Advent for the desolate

12 Stille Nacht

13 Winter 1946

14 Spring

15 The sad-eyed girl at the Victory

16 The girl from the lampshade factory

17 The Rathaus, where dreams are painted the colour of money

18 Closing the ring

19 The RAF’s prenuptial poke and prod

20 Bizonia as usual

21 Grand Place, Brussels

22 The Boothtown Road prodigal

23 A pawn takes a bishop

24 The witch before the wedding

25 16 August 1947

26 The end of the party

27 Manchester 1947

28 Life begins

For Friede: 1928–1999 Who was my love, my faith, my Heimat …

About the author

Harry Leslie Smith’s Guardian articles have been shared almost a quarter of a million times on Facebook and have attracted huge comment and debate. His book Harry’s Last Stand (Icon, 2014) received widespread praise, with Annie Lennox saying that Harry ‘is absolutely one of my heroes. Everyone should read this and be humbled.’ He lives in Yorkshire.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my thanks to the Bundesarchiv in Berlin, Germany, and the Hamburg City archives for allowing me to utilise their resources. Their assistance was invaluable in writing this book. I cannot express enough gratitude to my friends and my wife’s closest confidantes, Gerda Metzler and Ursula Overbeck, for their insights and assistance in my research about life in Hamburg during the 1930s. Your loyalty and your love, throughout the years to your friend Friede, is an inspiration. I am truly grateful to the kindness you have both shown me over the years.

I should also like to express my gratitude to the readers of my memoir 1923, who encouraged me to continue my journey into my past. I extend my thanks to my children and my grandchildren for having supported me in my endeavours to unravel our shared history. Vickie, Melanie and Cynthia, your thoughtful reading of my manuscript and your corrections have added immeasurably to the quality of my memoir. I am touched by the kindness and friendship you have all shown me.

I would also like to thank some men from long ago: Sid, Dave, Taffy, and Jack for being my mates. I hope you all found your way and grabbed some happiness out of this all too short a life.

I must also acknowledge my appreciation and thanks to: Walker, Locke and Cox; who were not only decent officers, but thoroughly decent men. They always did their best and deserve to be remembered for their empathy towards their fellow man.

Finally, I acknowledge my gratitude to all those people I have broken bread with while on this Earth. I hope your life was enriched as much as mine was by your company.

To the reader

It is autumn and it is wet and damp outside. I can already feel the approaching cold and heavy breath of the frozen months upon the nape of my neck. If I survive, this will be my 92nd winter on this Earth. Some say age brings wisdom, reason, serenity. I say bollocks; great age brings rheumatism, deafness, vascular degeneration and organ failure. So far, I have been lucky and my body has endured my storm-tossed life healthy and intact. It is a blessing I appreciate and honour every morning by performing the graceful movements of tai chi, which provides me the balance to combat the punishment that great age bestows on those who dare to live so long. We suffer the irretrievable loss of love, through death. We abide the profound loneliness of age as friends and lovers disappear from our grasp and are replaced with static photographs mounted high up on our fireplace mantel. I don’t ask for condolences or your pity because I have felt an elemental chart of wondrous emotions during my life. I have experienced the very best and the very worst that mankind has to offer. I have loved and been loved and that is a great matter. It is all that should matter. It is all that must matter, even to you, dear reader. So as I walk into the fourth season of life, I say accept love as it comes and accept love as it goes because it is the only currency that never devalues us.

I leave you now with a small piece of my life; my time in Germany following the last Great War. It is a simple story about people searching to belong and survive in a world that was almost destroyed.

Cheers, Harry Leslie Smith

CHAPTER 1

1945: The conditions of surrender

I don’t know why, but the winter rains stopped and spring came early in 1945. When Hitler committed suicide at the end of April, the flowers and trees were in full bloom and the summer birds returned to their nesting grounds. Not long after the great dictator’s corpse was incinerated in a bomb crater by his few remaining acolytes, the war in Europe ended. After so much death, ruin and misery, it was remarkable to me how nature resiliently budded back to life in barns and fields and across battlegrounds, now calm and silent. The Earth said to her children: it is time to abandon your swords and harness your ploughs; the ground is ripe and this is the season to tend to the living.

I was 22 and ready for peace. I had spent four years in the RAF as a wireless operator. I was lucky during the war; I never came close to death. While the world bled from London to Leningrad, I walked away without a scratch. Make no mistake, I did my part in this war; I played my role and I never shirked the paymaster’s orders. For four years, I trained, I marched, and I saluted across the British Isles. During the final months of the conflict, I ended up in Belgium and Holland with a unit that was responsible for maintaining abandoned Nazi airfields for Allied aircraft.

When Germany surrendered to the Allies in gutted Berlin, I was in Fuhlsbüttel, a northern suburb of Hamburg. At the time, I didn’t think much about Fuhlsbüttel, I felt it was between nothing and nowhere. It was much like every other town our unit drove through during the dying days of the war. Nothing was out of place and it was quiet, clean, and as silent as a Sunday afternoon. Our squadron took up a comfortable residence in its undamaged aerodrome.

While I slept in my new bed in this drowsy neighbourhood, the twentieth century’s greatest and bloodiest conflict came to an end at midnight on 7th May. On the morning of the 8th, our RAF commander hastily arranged a victory party for that afternoon. The festivities were held in a school gymnasium close to the airport.

The get-together might have been haphazard and the arrangements made on short notice, but there were no complaints because death was now a postponed appointment. Our individual ends, from road accidents, cancer, or old age, were to be pencilled in for a date in the far distant future. There was a lot of excitement, optimism and simple joy generated during the party because we were young and pissed on free beer. RAF officers, NCOs and enlisted men marked the passage from war to peace, dancing the bunny hop in the overheated school gymnasium.

No one considered or asked on that day of victory, ‘What happens next?’ That was tomorrow’s problem. I certainly didn’t question my destiny on that spring afternoon. Instead, like the Romans, I followed the edict: carpe diem. I ate too much, I smoked too much, and I drank too much. And why not?, I reasoned. The war was over and I had survived, whereas a great many had been extinguished as quickly as blowing out a flame on a candle.

I still didn’t want to think about tomorrow, even when our victory party was no more than a hungover echo of patriotic songs and dirty limericks playing inside my head; I was content to wait and watch. I was perfectly happy to observe my mates plod onwards like dray horses back to their old lives. I was satisfied to enjoy a moment that wouldn’t last, peace without obligation. I relished the mundane luxury of sitting on a bench with a cigarette between my fingers. I indulged in the sensual pleasure of feeling the warm spring sun hover over my face. I was liberated from home and the dismal dull world of a mill town, where one’s life was charted to end as it began: in a tenement house, under grey, dense skies. I wanted to simply enjoy and savour my release from the threat of death.

During those first few days of peace, I was overwhelmed with a feeling of good fortune. It was really blind luck that I had endured. My survival was the mythical lucky dip at a fairground raffle. I was alive while millions of combatants and civilians simply perished in this long and brutal conflict.

It wasn’t long after road workers had swept the streets clean from our victory parade that I began to realise my four years of service to the state hadn’t altered me greatly. Perhaps I was a bit more educated and less naive about the world. I had certainly acquired some now-redundant skills in marching and Morse code. I was also more aware that suffering and hurt was not a commodity in short supply. Possibly an outsider might have even considered me more cynical and crass after my years with the RAF. Yet underneath my cocksure attitude I was still the same self-conscious, lonely, awkward teenager who had volunteered to join the RAF in December 1940.

No matter how relieved I felt with Hitler dead and peace at hand, it reminded me that my personal destiny was now my own responsibility. Considering that the war had rescued me from the nightmare of my past life, I was a bit frightened by peace. I was comfortable in my RAF blue uniform, which made me look the same as Bill Jones, Will Sanders, or a multitude of other boys from counties all across Britain. I didn’t want to be Harry Smith from Halifax, former manager at Grosvenor’s Grocers, son of a cuckold, from the backside of town.

So for as many moments as I could grasp, I took smug comfort in the anonymity of military life. I relished the new laid-back approach both officers and NCOs took to commanding our group. It was a simple decree to live and let live. As long as there was no scandal, we were allowed to pursue our own pastimes for amusement or profit.

As the spring dissolved into summer, I began to appreciate that the war had been relatively harmless and uneventful for me. My life must change, I ventured, because I was one of the fortunate few; I was healthy and alive. The question was how to modify the existence that had been laid out for me since my parents’ rapid and one-way journey into poverty and rough living.

While shaving one morning in the wash hut, I said to my mate Dave: ‘I don’t know what to do with myself. I don’t want to be working at a mill back in Halifax or be a grocer.’

Dave took a while to reply because he was absorbed in taking careful strokes around his chin with a razor. ‘It’s all in the cards you are dealt before you are born. Some get a lucky hand while others get shite. If all you get dealt is deuces, there’s nothing you can do about it, except learn how to fucking bluff.’ Dave paused, looked at his clean face, and added as an afterthought to the rules for a successful life: ‘You also need a good fry up in the morning.’

Was he right? Was it just down to luck? He might have been on to something. So far, every direction my life had taken was a simple act of chance or whimsy. After all, flat feet and a flaccid patriotic sentiment led me to the doors of the RAF. Most likely, had I picked another branch of the armed forces, I would have ended up as a name stencilled on a cenotaph to be washed in the indifferent rain falling on Halifax. So, for the present, I left my life in the hands of fortune reinforced by bullshit.

On the days I was permitted to leave our base, I strolled until my legs ached, exploring my surroundings as if they were the ruins of Troy. To remain alive in 1945, the Germans were reduced to the most primitive form of commerce: they bartered and begged, and they did it in every imaginable location. I encountered Germans in back alleys, on street corners, or by the entrance to the train station, huddled in small groups trading their heirlooms for food.

In the beginning, I was emotionally detached from Germans and the destruction around me. Their suffering played as blandly as a sepia-toned newsreel at the Odeon cinema. The immensity of the pain endured by both the innocent and the damned was too much for me to absorb. What lay outside of my privileged life in camp was a festering sore that fouled the air. I tried to keep my distance from the Germans and their troubles.

Keeping my heart cold and lofty didn’t last long because I was a young man looking for a bit of emotional adventure. Within two weeks, I was trying to start conversations with young German women. When I called out, ‘Excuse me, Fräulein,’ most walked by me or jumped over to the other side of the street. Some women smiled politely or giggled to their girlfriends at my bad accent and limited vocabulary.

This game ended for me on the day I travelled up Langenhorner Chaussee, in Fuhlsbüttel. It was a road populated with attractive two- and three-storey apartments, which were shaded by linden and cherry trees. It was a middle-class neighbourhood that stretched towards the horizon in relaxed prosperity. The street was a quiet and pleasant quarter that seemed immune from the tragedies unfolding all around it. It wasn’t until I walked further up the road that I discovered no district in Germany was inoculated against hunger.

On the other side of the street, a commotion was brewing between an elderly man and a young woman. They were haggling over the value of a silver fork for a packet of cigarettes. I loitered and observed them struggling to barter their way out of starvation and ruin. Suddenly, I noticed a woman who made my heart and head stumble in aroused confusion. It appeared she was also bartering for food, but there was something different in her body language. It suggested to me a dignity and a pride that wouldn’t yield to her circumstances.

Extraordinary, I thought; and I said aloud, ‘You are beautiful.’ Afterwards, I did something rash: I displayed a confidence I generally lacked, unless full of beer. I barged into the young woman’s life. It was reckless, it was foolish, and perhaps it was even desperate. It also proved the extent of my loneliness and my habitual foolishness to fall in love with foreign things. During our first encounter, she was moderately indifferent to my entreaties. Perhaps she was even amused by my stilted German and my pushy courteousness. On instinct, or possibly it was a girlish whim because I seemed harmless, she graciously allowed me to walk her part-way home.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

‘Elfriede Gisela Edelmann,’ she quickly responded.

I tried to repeat the name, but it jumbled out horribly wrong.

She laughed and said, even though we weren’t yet friends, ‘Call me Friede, it is easier.’

I must have left a favourable impression because Friede agreed to meet me for a picnic the following week. So began my slow and irresolute courtship with this extraordinary German woman.

Perhaps the term ‘woman’ was too advanced because she was only a teenager. However, at seventeen, Friede had more style, sophistication and charm than anyone I’d ever met, dated, or simply lusted after. She possessed a sense of mystery because there was something unknowable and impenetrable about her personality. It was as if there was a sunspot against her soul. Perhaps Friede created this emotional no-man’s-land around herself because she had encountered evil in Hitler’s Germany, or perhaps because she harboured some unhappy family secret. Whatever the reason, she was an enigma who was hard to fathom, but easy to love.

It was primal, it was emotional, and it was natural, but I wanted to get to know her better. I also wanted to sleep with her and I would do anything to get to that end. At first I took her on innocent picnics. I snatched food and wine from the RAF mess hut for our meals. I believed I was being cavalier. I thought Friede might even consider me cosmopolitan when I lit our cigarettes like Paul Henreid for Bette Davis, in the movie Now, Voyager. She only smiled or laughed lightheartedly at my decorum. Initially, I didn’t understand that she lived in a completely different world than mine. Her universe had more immediate problems and concerns than if the wine was chilled. After a while, I began to understand that her community was in serious trouble and was suffering from a severe lack of food and medicine.

It was during an afternoon lunch on the banks of the Alster River that some of her real misfortunes and sorrow crept up on me. While she sunned her bare legs, I noticed they were covered in tiny blisters and ulcers. Friede registered my awkward stare and smiled.

‘We have no vitamins, liebchen. There’s nothing left to eat: all of Germany will die from scurvy, like we are on a polar expedition.’

‘Why don’t you have any vitamins?’ I innocently asked.

Friede explained that for most Germans, the last year of the war had been very difficult. Their cities suffered round-the-clock bombardment, while the Allied armies began a massive land offensive against their nation. In the final months of the war, food supplies for ordinary citizens ran out. Friede and her family lived off a soup that tasted like rainwater and ate bread made from animal feed.

‘After the Russians crossed the Oder River in January 1945,’ Friede explained, ‘everyone knew the war was lost. It was only a matter of time before we got a taste of our own medicine. I was terrified because I didn’t know who our new masters would be: Russia or America?’

‘It was a good thing we Brits got here first before the Russians could get their hands on Hamburg,’ I replied.

Friede laughed at my simplistic response and retorted, ‘It is sometimes hard to tell if Britain is the best jailer. You British treat everyone as if they are Nazis and deserve to be punished.’

‘How do we do this?’ I asked.

Friede looked at me and smirked. ‘Our rations are table scraps for a dog. People are expected to remove rubble from the cities, but are allotted just 1,200 calories of nutrition per day. Britain keeps my people on the edge of starvation. Have you seen the bread they give us?’ she demanded angrily.

I had seen Germans queue impatiently for this almost-inedible food. At one time, I had even witnessed soldiers toss dense bricks of blackened dough to hungry crowds. It was a miserable ration to feed anyone. The ingredients were a dubious mixture of sawdust and salt, with a trace amount of flour that bonded the indigestible product together. The bread was baked in the morning and if you didn’t consume it by late afternoon, a thick green mould would burrow its way to the crust. Sometimes, I caught sight of vagrants in the shadow of bomb-damaged buildings who had somehow got their hands on the thick, rotten bread. Famished, they would stuff it into their mouths and wash it back with water scooped from the street gutters.

Friede said that many believed the victors treated Germany like they did in 1918. ‘The Allies will let the German people starve to death.’

‘What do you mean?’ I asked defensively.

‘Unless you are wealthy, you can’t buy food anywhere in the city. Mutti must travel north up into the countryside,’ Friede told me in a halting voice. ‘She sells our belongings to the farmers who give her a few eggs and a rotting turnip in exchange. How will we live once all of her jewels and silver are gone? Mutti says the farmers act like pirates. They have no pity on the city folk and will rob you of everything you own for a morsel of food. People say the farmers are rich from the city’s misery and have Persian carpets in their pigsties.’

Afterwards, I thought my invitation to a lunch by the river seemed nothing more than a cynical gesture. I blamed myself for not understanding her difficulties sooner because I had endured a similar hunger in my childhood.

My growing affection for Friede drove me to become a conspirator in her survival. I obtained food for Friede and her family by the old and reliable methods my mother had taught me: if you can’t buy it, beg for it, and if you can’t beg for it, nick it while God and the holy ghosts are down at the pub. So, from storage units on our base, I snatched anything I thought useful to them, from food rations to soap and medicine. I wrapped up the contraband in a blanket and smuggled it out of camp in a haversack.

Perhaps I was correcting the wrong done to me as a starving boy? Perhaps I was buying love and loyalty with a loaf of bread? I didn’t know or care. I knew winter was coming and without someone like me, her family would starve to death like thousands of other Germans, hobbled by this devastating war.

Looking back, I think the start of our romance – the picnics by the river, the afternoons spent loitering in riverfront cafés – were just a pleasant diversion for Friede and her friends. They were an excuse to eat delicacies and savour flavours long absent from an ordinary German’s diet. In the beginning, Friede didn’t appreciate the ardour of my passion, but enjoyed my diligence and loyalty in trying to please her ordinary desires and satisfy her most basic needs. I was able to provide Friede with food and protection in a nation that had been cast out of civilisation. It was my sheer persistence to keep her sated and healthy with purloined wine, preserves and medicine that allowed me to ingratiate myself to her. I was able to transform our relationship from the formal Sie to the more hopeful and friendly du.

It was easy for me to fall in love with Friede because she was as glamorous as a movie star. She had deep, expressive hazel eyes, and raven hair that hung voluptuously to her shoulders. Her face was sensuous and, at times, mysterious as it expressed deep emotions and indefinable longing.

With my background of poverty, infidelity and family betrayal, Friede was everything I couldn’t aspire to in England. Her education, her taste, her style were vastly more sophisticated then my Woolworths’ tuppence upbringing. Being arm-in-arm with her, I felt like I was a lead character in a Saturday morning movie serial. I fell hard for Friede and plunged into the deep end of German life under occupation. Yet the bottomless, almost un-navigable water of love in a ruined nation was my best option for a better future. It was certainly better than returning to a wet and dreary existence in Britain.

Unfortunately, Friede wasn’t as easily convinced of my long-term suitability as either suitor or provider. In the beginning, my loyalty and my love were chided as unproven and a childish fancy. Besides, she said, ‘Tommies come and go; you too will leave for England and go back to your English girlfriend.’

I protested, but she was right – the end of my time in the RAF was nigh. Demobilisation of soldiers and airmen was moving at a steady pace. If I didn’t act quickly, I was going to find myself demobbed and marching in a victory parade leading me right to the dole queue. If I truly loved Friede, as I so often claimed after a half-bottle of Riesling, I would have to find a means to remain in Germany. My only option was to extend my services with the RAF.

CHAPTER 2

Staying on

Considering that I came from the rough streets of Barnsley, Bradford and Halifax, extending my term with the RAF was an easy decision. There was nothing in Yorkshire for me except the dead footfall of orphaned hopes and dreams. I had neither an education nor a vocation. Before the war, I had been a manager at Grosvenor’s Grocers in Halifax. Prior to my departure for military service, the owner had promised me that my position would be available at war’s end. A lot can happen in four years and promises made in patriotic fervour are kept as seldom as New Year’s resolutions. My old job was no longer available. It had been taken by a conscientious objector who dodged the draft but never an excuse to make a pound.

By the age of 22, I had an empirical certitude that there was nothing for me in England. Everything I cared for had been destroyed by the Great Depression. My father had spent his last years alone in a doss house and died a pauper. As for my mother, Lillian, she was still alive, but our relationship had been tested and damaged by extreme poverty. She secretly defied the conventions of our working-class heritage by having a love affair with a former cowman named Bill Moxon, while still married to my father.

Sometime between my seventh and eighth birthday, the cowman replaced my Dad in both my mother’s heart and her bed. However, there was no happy ending for them, for my Dad or my sister and me. You see, outside our ramshackle house, the Great Depression descended like a plague upon Yorkshire. My world, along with that of the rest of Britain’s poor, became a dog-eat-dog existence. I spent my youth flitting from one slum to the next, grabbing my education on the run and feeling that my future was to end in a miserable squat. I knew that the war had saved me, and in peace I was not going to return quietly to a life of rank poverty or into my mother’s emotionally unstable gravitational pull.

So, it never crossed my mind to move back to my mother’s because it would have been as distasteful to me as returning to a crime scene. The only emotion I had for my mother was despair. As for Halifax – the city my family came to call home after we had lived a vagabond existence that took us from Barnsley to Bradford and many points in between – it only elicited in me an overwhelming feeling of stale disappointment. Therefore to return, after my stint in the RAF, to the tenement my mother shared with her cowman and my two younger half-brothers would have been a step backwards into the grey world of the 1930s.

In 1945, I had no attachments to Britain except for one person who still tugged at my shirt-sleeves: my sister Mary. She was my true friend and companion through our family’s bleakest and saddest moments. But my affection for her wasn’t strong enough for me to flee back into the oppressive and stifling arms of Britain’s West Riding.

Besides, Mary didn’t have the means to put me up, even if I did want to return home. She lived on the steep hills of Low Moor, in a tiny terraced house with a young son and a troublesome husband. Nor did Mary have any influence with the local powers to find me employment; without a friendly word in a manager’s ear there was no possibility of a job. The mills around Bradford and Halifax were brimming with unemployed servicemen, all looking to return to their old positions. If I went home, I would be just another redundant cog in the broken wheel of British industry.

Just to make sure I wasn’t under any delusion about life back in Yorkshire, Mary wrote to me: ‘Luv, there’s nothing here for ya. There’s nothing at all, no housing and certainly no brass. If you need it, I can always lend you a spare shilling. But I suspect you’ve got more than me, being in the RAF. But I won’t deny you anything I’ve got; which is love and a shoulder to cry on. Stay put, stay safe and stay out of our Mam’s way or she’ll be asking for something from you. Enjoy your time abroad because you’ve got nowt to come home to.’

So there was nothing and no one to return to in post-war Britain. I knew I was more welcome walking outside the gates of our encampment down Zeppelin Strasse than on Broad Street in Halifax. So I was content to be across the North Sea in a foreign and defeated country. In fact, I was better off stationed in this desperate and ruined nation than in Britain. At least in Germany I was a member of the conquering legion. The RAF protected me from want and hunger. In exchange, I accepted that my life was theirs to waste in battle or in peace. However, in the spring of 1945, it was unlikely that the RAF was going to collect on the balance owed them. My life wasn’t in any immediate danger in Europe and I wasn’t going to remind them about the battles still under way in Asia.

Some of my mates had different notions about self-preservation and suggested I join them on an insane venture in the war against Japan. Their mission involved a self-propelled, one-man submarine in the South China Sea; the sub would affix limpet mines to the remnants of the Land of the Rising Sun’s merchant marine. The scheme and their rationale – ‘Be a bit more of a laugh than hanging around ’ere’ – was lunatic at best and suicidal at worst. Considering that since my induction in the RAF, I had avoided volunteering for anything that might shorten my life with as much rigour as I ducked Sunday church parade, I wasn’t going to break my lucky streak by accepting a suicide mission to the Far East, just to satisfy our dying empire or my more patriotic, testosterone-driven mates.

No, I wasn’t going anywhere dangerous. I would remain in Germany because they were defeated, broken and submissive. It was the safest place in the world for me to figure out what I wanted to do with my life. I knew I wasn’t cut out to live as my parents did on bread, drippings and bitter. Besides, staying on allowed me the time to pursue Friede. I wanted the opportunity to win Friede to my heart and I believed it was going to be like most of the crooners’ love songs that played on Armed Forces Radio at the time – a beautiful melody that ended happily ever after.

Now that hostilities were over, the RAF had minimal expectations for the lower ranks. Their one simple rule was: keep your head down and your nose out of other people’s business. I had no problem with this unwritten regulation as I had followed this practice since boyhood. As long as it didn’t affect my immediate well-being, the petty affairs of others didn’t rouse any interest in me. It was safer to close my eyes to everyone’s evil or saintly exploits.

After all, if I wished to remain in Germany, there was wisdom in silence. I wanted to be known and relied upon for my indifference to the comings and goings of the world around me. Keeping out of trouble was one thing, trying not to witness trouble was impossible. Two weeks into our stay in Fuhlsbüttel and the profiteers were salivating at the opportunity to plunder an occupied country with no inventory list. Supplies from food to fuel were always going missing. One morning, a sergeant put a friendly arm around my shoulder after I noticed a group of airmen suspiciously hanging around a store house. The NCO said: ‘Lad, keep your eyes shut and whistle a friendly tune because there’s nowt to see here.’

The men I encountered were shifting boxes of tinned meats, preserves and beer into an Air Force van, which when loaded took off for an unknown destination. Later on, I mentioned the truck with its cargo of RAF stores to a hut mate and friend named Sid.

‘Oh that,’ he said. ‘It’s a sergeant’s fiddle. He’s got some deal with a bloody Nazi who owns a restaurant. The sergeant provides him booze and meat. In return, good old Fritz pays him in gold coins and jewellery.’

‘What happens to the baubles?’ I asked foolishly.

‘The missus flogs it back in Leeds.’

My mouth opened up to respond, when Sid said to me: ‘Don’t even think of joining that party, mate. It’s best we stick to what we know: getting pissed and getting laid. Everything else is a big boy’s game.’

‘Too right,’ I agreed.

So in the interest of self-preservation, I did what I was told. I turned a blind eye to my equals and my betters. I turned my back to anything that appeared out of sorts. I even closed my ears to the sound of coins being counted in the darkness by those who were plundering the German nation or the British armed forces. However, as the weeks progressed, it became more difficult to ignore the racket caused by the pilfering. It seemed anything of value, if it wasn’t guarded or nailed down, was nicked. Some members of my squad acted as if they had found bits of a Spanish galleon washed up on shore when they returned from a trip into Hamburg.

‘Jesus wept, would you get a look at that watch. It only cost me a carton of bloody Lucky Strikes.’

‘Jim, if you’d spent forty years in the pit as a ripper, you’d still not get a watch as fine as you traded today, for a bunch of bloody fags.’

With a nation being hawked away for cigarettes, I wasn’t going to be left out of this burglary. I took what wasn’t mine, but I reasoned it was an altogether different type of crime. My larceny was innocent of profit or malice. I simply pinched food for the German girl and her family. My misdemeanour was insignificant except to those that received my food parcels. I thought my actions were more akin to extending the hand of British philanthropy towards the less fortunate.

On base, there were a few others like me, unwilling to profit from the misery of others. We were incapable of seeing a reason to garner personal gain from the sunken and ashen faces of bomb-battered ordinary Germans. As for the rest, the temptation for theft and for sex without responsibility was overwhelming. It was too easy for them to suspend their morality while abroad. They believed that their ethics could resume upon their return to Britain. They thought their moral code was like a light switch; it could be turned on or off without ever marking their soul.

Within my barracks, a great many used food and cigarettes as a bartering device for nameless sex with near-starved German teenagers. Others traded food for gold, jewellery and other valuable commodities, which they saved for their return home to Brighton or Birmingham as chocolate soldiers on parade. Their dubious earnings from fraternising with the desperate provided a valuable addition to a down-payment on a house or a new car. Others just frittered their money and morality away as if they were down at their local pub with their pay packet.

‘For a bit of coffee or nylons, you can get those Fräuleins to do anything you want.’

‘Smith, why don’t you try it, if only for a laugh? You’ll never get a chance like this again, ever in your sorry life.’

But I shook my head. I had already experienced life at the hands of ghetto kings back in Bradford and had no wish to become a proper bastard in Germany. ‘Sorry, lads, I don’t want anything from the bloody Germans because they’re nothing but trouble,’ I remarked.

Someone at the far end of our hut shouted out: ‘We got Jesus of the Nazarenes sleeping beside us. Let’s hope he doesn’t go to turning tables at temple on Sunday.’

I laughed. ‘Bugger you, mate. There will be no water into wine for you ungrateful lot.’ I went back to reading my book.

A few days later, I spoke with my friend Taffy. ‘I wonder if things had worked out different in the war and Jerry was on our High Street buying us out for a thruppenny, how we’d take it?’

Taffy was Welsh and as sentimental as me. I liked him for his love of poetry and whisky, and his soft touch for hard-luck stories.

‘Pack it in, Harry,’ Taffy said. ‘Most of those lads are like us; since the day they were born they’ve been beaten down by the squire, by the church, and by the foreman. All they want is to taste a bit of the good life after being cheated out of it for centuries by those Tory bastards back home. Sure, they shouldn’t be filching, whoring, and acting like clowns on parade just because no one gives a toss. But I’ll keep schtum to their misdemeanours and leave it up to God to decide who’s guilty and who’s innocent.

‘As for Ali Baba over there and his forty thick thieves; leave ’em be. Germany is a land of louts and I’ll be glad when I am rid of it and back home in Wales. You should go home too. Forget this place; it’s filled with bloody foreigners.’

Even though it disgusted me, Taffy was right about the pilfering. So I kept quiet. I didn’t want my larceny to be revealed or curtailed, or for me to be punished for helping the German girl.

It was both terrifying and exciting keeping Friede’s family afloat while the former German nation collapsed around us like a block of condemned buildings. It was also a giant fraud because my gallantry was circumstantial. I only appeared successful and confident to Friede because her country was decimated. Every day, I was frightened that Friede would discover my counterfeit, that my ability to save her was limited to my present circumstances. Anywhere else, I would have been just one of a hundred men, searching for work and shelter.

It scared me to think that Friede or anyone else might discover that my outward confidence was a swindle, a deception as devious as a cheque written on a bank account with a nil balance. So, there was no turmoil in my soul when I made an appointment with my superiors to extend my days in Germany. I had only one anxiety: that perhaps the RAF didn’t want me and were prepared to chuck me over the side, once my terms of service were complete.

Before my scheduled appointment, I made sure that I was properly groomed. A German barber cut my hair and shaved me with a straight-edge razor. My uniform was pressed by a woman who worked at the base laundry. I was determined that my outward appearance would convince any officer that I was born for the military life. After a quick cigarette behind a Nissen hut, I marched over to the group captain’s office where I was to meet with his adjutant. When I arrived, the foyer was littered with other men in similarly pressed uniforms. We looked like lackeys begging for favours in the Sun King’s antechamber. The adjutant had a wiry LAC (leading aircraftman) for a secretary, who acted more like a guard dog on an estate than an administrative clerk.

I announced myself to the secretary, who scanned a large appointment book for my details. Out loud, he called out a roll of names pencilled in for meetings with the adjutant: ‘Benson, Hearn, Simpson, ah yes, and here we are, Smith. Your appointment is at 1:45. Bit eager, aren’t we?’ he said.

‘Pardon?’

‘You’re early for your appointment.’

‘It’s only five minutes away,’ I pointed out.

The clerk looked up at the wall clock, back to his wristwatch, and then smiled at me. ‘You’re still early. Please take a seat.’

The secretary returned to his duties and I was left to watch the minute hands from the clock make five slow revolutions. At 1:45, the clerk robotically stood from his desk and knocked on the officer’s door. He entered and returned to the foyer.

‘The adjutant is ready to see you.’

I stood up and the secretary admonished me.

‘Come on now, let’s get a move on, chop, chop. We don’t have all day; the adjutant is a busy man. It’s not like going to see the parson, you know.’

The secretary announced me to Flight Lieutenant Locke, the adjutant. ‘Wireless Operator Smith to see you, sir.’

The officer was at his desk signing papers; behind him was a wall map of northern Germany. He looked up from his work and said, ‘At ease, Smith.’

He had a waxed moustache and was at least ten years older than me. It was a kind but weary face. I noticed he was wearing a wedding band. On his desk were framed photographs of a blonde-haired woman and a little girl.

He pulled open my file, read it quickly and said: ‘So you want to stay on in Germany. Any reason for this? I hope this isn’t about a girl.’

‘No, sir,’ I said. ‘I like the Air Force and I enjoy the life. I think I can contribute to my country better in uniform than out.’