Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

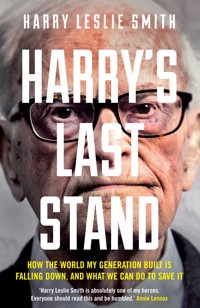

'A kind of epic poem, one that moves in circular fashion from passionate denunciation to intense autobiographical reflection ... should be required reading for every MP, peer, councillor, civil servant and commentator. The fury and sense of powerlessness that so many people feel at government policy beam out of every page.' The Guardian 'It is not enough to read Harry's record of the struggles and hopes of a generation – we have to re-assert his principles of common ownership and the welfare state. If Harry can do it, we should too!' Ken Loach, Director of I, Daniel Blake 'As one of the last remaining survivors of the Great Depression and the Second World War, I will not go gently into that good night. I want to tell you what the world looks like through my eyes, so that you can help change it…' In November 2013, 91-year-old Yorkshireman, RAF veteran and ex-carpet salesman Harry Leslie Smith's Guardian article – 'This year, I will wear a poppy for the last time' – was shared over 80,000 times on Facebook and started a huge debate about the state of society. Now he brings his unique perspective to bear on NHS cutbacks, benefits policy, political corruption, food poverty, the cost of education – and much more. From the deprivation of 1930s Barnsley and the terror of war to the creation of our welfare state, Harry has experienced how a great civilisation can rise from the rubble. But at the end of his life, he fears how easily it is being eroded. Harry's Last Stand is a lyrical, searing modern invective that shows what the past can teach us, and how the future is ours for the taking. 'Smith's unwavering will to turn things around makes for inspirational reading.' Big Issue North '[With] sheer emotional power ... Harry Leslie Smith reminds us what society without good public services actually looks and feels like.' New Statesman

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 259

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HARRY’S LAST STAND

HARRY’S LAST STAND

HOW THE WORLD MY GENERATION BUILT IS FALLING DOWN, AND WHAT WE CAN DO TO SAVE IT

HARRY LESLIE SMITH

Published in the UK and USA in 2014 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by Jonathan Ball,

Office B4, The District, 41 Sir Lowry Road,

Woodstock 7925

Distributed in Canada by Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3

Distributed to the trade in the USA

by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101,

Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

ISBN: 978-184831-726-0

Text copyright © 2014 Harry Leslie Smith

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in MT Bell by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

To my Mum and Dad

Albert and Lillian

Who lived and tried to love in a time of austerity

Contents

Prologue

A Day in the Life

Live to Work

Everything Old is New Again

The Green and Pleasant Land

Eventide

Acknowledgements

I said: What is past shall be no more, shall be no more! …

But lo! They have started to stir again …

—Alexander Pushkin

Prologue

I remember how peace smelled on that day in May 1945. Of lilac, petrol and the rotting flesh of the dead German civilians entombed beneath the fire-bombed city of Hamburg. I was 22 years old. After four years of fighting with the RAF, I had survived and been given the chance to grow old and die in my bed. It was a day to weep for those that had been lost but also to dance and celebrate life, to drink to our good fortune.

There has not been a day in the last 60 years when I have not thought of how lucky I was. However, as I have grown older, I am no longer certain that the sacrifice my generation paid with their blood was worth the cost. Back then the people of Britain stood strong, unwilling to surrender to the tyranny of fascism, despite unimaginable civilian casualties and privations caused by the bombing that laid waste to our cities and industries. Our armed forces, comprised of boys from every compass point on our island, knew that their lives might be wagered and their futures extinguished so that our nation, our way of life, might endure. Young lads became men in the desperate clash between civilisation and barbarism.

After six years of total war, millions of casualties, millions of dead, millions of maimed lives, Britain and her allies were victorious against the scourge of Nazism. But that is not the end of the story. My generation’s resolve to create a more equal Britain – a more liberal world for our children to grow up in, where merit mattered and the class system was history – was set on the battlefields of Europe.

In November, when our nation remembers her fallen soldiers and honours the lost youth of my generation, the Prime Minister, government leaders and the hollow men of business affix paper poppies to their lapels and afford the dead of war two minutes’ silence. Afterwards, they speak golden platitudes about the struggle and the heroism of that time. Yet the words they speak are meaningless because they have surrendered the values my generation built after the horrors of the Second World War.

We fought in tank battles in the Sahara. We defended the skies over Britain in dogfights with the Luftwaffe. Our navy engaged in a life-or-death conflict in the battle of the north Atlantic to preserve our dominion over the seas. We were compelled to invade the armed fortress of Europe on the beaches of Normandy. In desperate battle we fought the Germans from village to town through spring and summer in our bid to liberate France. As autumn turned to winter our armies, along with those of our allies, formed a united front that pushed through the lowlands of Belgium and Holland. Those final months of conflict were intense, brutal and bloody but we buggered on until we were in the heart of Germany and on the road to Berlin and victory.

When we accepted rationing and the lack of decent housing during the post-war period of reconstruction, it was because after the bloodshed we were all focussed on building something better for everyone. And for a while it seemed that the enthusiasm that blossomed in Britain, America, France and Canada for the creation of thriving societies for the poor, the working classes, the middle classes and the wealthy would endure. It seemed genuinely possible to create nations that combined social justice with economic mobility for every citizen.

But it didn’t last. By the 1970s the British economy, as well as its society, was under serious threat from inflation, weak Labour governments that weren’t able to stabilise the nation’s finances or control the chaos and misery that average citizens endured from an endless array of industrial strikes. In that tumultuous decade it felt like the United Kingdom had lost the plot and overreached itself in its desire to build a just society through financial stability and fair play to both worker and employer. Picket lines formed like flash mobs out of nowhere and for no apparent reason. At any given moment lorry drivers, coal miners, grave diggers or refuse collectors were on the streets demanding wage settlements that were meant to offset the horrendous cost-of-living crisis caused by inflation. However, for those who were not protected by a union it smacked of an ‘I’m all right, Jack’ attitude.

The 1970s were a tumultuous decade for the world’s economies, but the rot really started to seep into Western democratic nations in the 80s, after the oil crisis and years of hyperinflation and chronic labour unrest. To my mind, the edifice of our civilised states started to crumble the day Ronald Reagan talked about the shining city on the hill that could be built without taxes, and when Margaret Thatcher said that come what may she would not be turned, no matter how many tears were spilled in her destruction of those who protected workers’ rights. Those that had never experienced it began to talk about a golden age when taxes were low and opportunities were always available for hard workers, while the lazy perished in their own sloth.

In two short generations the tides of corporatism without conscience began to roll in and washed away the blood, sweat and tears of a hundred years of industrial workers’ rights. Now, a nation that once had the courage to refigure society, to create the NHS and the modern welfare state, elects governments that are in lock-step with big business whose overriding pursuit is profit for the few at the expense of the many. We have gone from a nation that defied Hitler while the rest of Europe lay subjugated under his boot to a country that is timorous around tycoons and their untaxed offshore wealth.

These technocrats and human resource experts have reversed my generation’s struggle to close the gap between the richest and the poorest. They have betrayed our dream of an equitable society with medical care, housing and education for all. They have allowed it to be taken to pieces and sold off to the lowest bidder, and broken their pledge to protect democracy and the freedoms due to every citizen in this country. This cannot be allowed to happen in respectful silence. Too many good people died. Too many sacrificed their lives for ideals that have been too quickly forgotten.

Austerity, along with the politics of fear, is being used in this country like an economic Marshall Law. It has kept ordinary citizens in line because they are fearful of losing their jobs, being unable to make their rent, their credit card or mortgage payments.

In recent times, our governments and the right-wing media have toyed with our nervousness over the economy, over the state of the world and over our personal lives like they are poking a fire. They have sold fear to the people like the markets sell fish on Friday. We are mesmerised by this fear, stoked in a cauldron of sensationalist tabloid headlines about immigration, welfare cheats, sex scandals and militant terrorism out to extirpate Western civilisation. This perpetual war on crime, drugs, terror, immigration and benefits cheats has turned us into a society that distrusts the unknown, the weak, and the poor, rather than embracing our diversity. We have become hyper-vigilant about imaginary risks to our person and our society, but indifferent to the threats that austerity creates to our neighbourhoods, our schools, our hospitals and our friends.

Sadly, the politics of fear work. People have grown indifferent to the concerns of those who are less well off than them. It is only natural because, after all, it’s a hard scrabble life for the vast majority of people in Britain these days. We have become so consumed by our personal shifting economic fortunes that we can hardly be expected to think about anyone else’s. We worry, we fret; we fear for our own health and our children’s safety and future. We are now always in a panic about our jobs, about our inevitable redundancy at work. We are stressed by the health of our parents and whether they can make do on their pension pot. We worry if we can save enough to be free of work for a few years before death takes us. Ultimately, we are afraid that we will be like the people from my world in the 1930s. We don’t want to be like our ancestors: never able to rest, always working until we are no good for anyone and then left to die alone in some darkened corner of this island.

The middle classes are so afraid that they will become as dispossessed as the poor that they have allowed the government to use austerity as a weapon against them and their comfortable way of life. But hospital closures, bad roads and stagnant wages, along with stern cutbacks to the social welfare system affect us all – not just the indigent. I have been through this all before, and I don’t want future generations to suffer as we did.

My generation never forgot the cruelty of the Great Depression or the savagery of the Second World War. We promised ourselves and our children that no one in this country would ever again succumb to hunger. We pledged that no child would be left behind because of poverty. We affirmed that education, decent housing and proper wages were a right that all our citizens deserved, no matter their class.

Throughout the years, my generation was vigilant in keeping our word to the younger generation to ensure that they did not encounter want during their lives. As a society, we fought for equal pay for equal work; unions struck for better working conditions; many organisations endeavoured to end systemic and institutional racism, while others fought against the poll tax. However, my generation grew weak through age and our resolve declined. We gradually stopped our defence against those who sought to puncture the umbrella of the social welfare state.

I suppose we had hoped that our children would keep the torch of civilisation burning while we moved into our senior years. But something happened and their resolve wasn’t as strong as ours. Perhaps they got caught up in the heady world of consumerism and thought that happiness could be bought at a shop or found on an all-inclusive trip to the Bahamas, or perhaps they simply felt impotent in the face of such hardship. Whatever the reasons, from the 1980s onwards, the right-wing and New Labour governments nudged us to believe that the state was too big and needed the Midas touch of business to get it running right. Council estates were sold off, railways privatised, water put into the hand of big business. Slowly and surely, Britain and the West became societies that repudiated cooperation and socialism for corporate endeavours.

Now we live in an era when it is difficult to protect the advances made to society through our welfare state. The social safety net has been sheared by privatisation and policy makers who oppose the justice it delivers to all citizens. There are too many corporations who rely on zero-hour contracts to make enormous profits that are invested in offshore tax havens. We are losing the battle against poverty because governments and businesses won’t address the disparity of wealth between those at the top of society and those who exist in the heap. Unless hunger, prejudice and rampant poverty are curtailed this nation will lose a generation, like it did mine.

When I talk to you about my past, I do so not through some golden-tinged nostalgia, or, like Monty Python’s famous Yorkshiremen, in some spirit of competitive suffering, but because until you know what led to the creation of these aspects of our society, which are now so lightly discarded, you cannot understand why they were necessary. Until you have lived through a world without a social safety net, you cannot understand what the world our leaders will leave as their legacy will be like. You cannot feel it in your marrow.

I am not a politician or an economist. I don’t have a degree in PPE from Oxbridge – and I’m sure those who do will be able to pick holes in what I say. But I have lived through nearly a hundred years of history. I have felt the sting of poverty, as well as the sweetness of security and success, and I don’t want to see everything we’ve worked for fall apart. As one of the last remaining survivors of the Great Depression and the Second World War, I will not go gently into that good night. I want to tell you what the world looks like through my eyes, so that you can help to change it.

A Day in the Life

I. First light

I woke earlier than usual this morning. My eyes opened as the sun clambered over the horizon. I lazed for a while underneath the covers, longing for the warmth of my wife, Friede, beside me, her voice whispering in my ear. I turned my body towards the wall and stared at her picture on my bedside table, a holiday pose taken a long time ago. She has been dead for more than a decade.

Getting dressed I wonder how long I have left. How many turns of this earth will be granted to me before I am just a photo on someone else’s mantelpiece? Perhaps it’s maudlin to dwell so much on death before breakfast, but it cannot be helped when one is 91. Death will soon come and like a publican ring his bell for last orders. At best, I have a matter of years and at worst a fluttering of months before I am dead. What is certain is that I will be gone sooner than most of you, like smoke rising up from an extinguished candle. As a son, a brother, a lover, a husband, a father and a friend I will be no more.

There will be no hymns sung on the day of my funeral. My will stipulates that there be no religious service. I have seen too much of man’s wickedness to believe that this world was divinely created. And, if I am wrong, as I have been on so many other matters, I am sure that God can find it in himself to forgive me my trespasses. But there will be a wake. I have left provisions to stand my round so that those who held me close can raise a glass of beer or whiskey to my name. Later on, when the sun is high and warm, my ashes – along with those of my long-dead wife and deceased middle son – will be scattered in some serene part of Yorkshire, where I was born.

Though I am not an historian, I am history. I look back and wonder how it was possible for me to have survived the turmoil that I did. How did I make it all the way from newborn to pensioner? I don’t know. Perhaps it was luck or guile, or maybe it was a combination of the two. Yet, somehow I managed to survive the Great Depression, the Second World War, Britain’s post-war austerity, the upheaval of the 1960s and 70s, the threat of nuclear terror during the Cold War and this perpetual, self-renewing, self-fulfilling war on terror.

Since my birth three kings and one queen have reigned over Britain, while 21 prime ministers have ruled. During the span of my life, humanity has stumbled through revolutions, wars, economic booms and economic busts. I have seen the great and infamous bring wisdom and wreak havoc upon the world. Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Churchill, FDR, de Gaulle, the Kennedys, Eisenhower, Nixon, Thatcher and Reagan have all been and gone. As a teenager, I remember watching the newsreel footage from the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War, and as a middle-aged man I listened to radio reports about the war in Vietnam. As an old man I have borne witness to man’s greed and bloodlust as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have unfolded.

Nothing ever bloody changes, it seems, except the style of clothes we wear. I have travelled the world and experienced the wonders of new continents, ancient civilisations and societies on the verge of collapse. Yet everywhere I have been, I have remembered my grandmother’s blessing, spoken to me as a boy growing up in utter poverty in Yorkshire: ‘Yer Barnsley bred and born. Nowt time, nowt brass is ever going to change that for thee lad, where ever thou may roam.’

Now, it is as if I am living two lives. That of the present day, but with all I have ever seen in the past lying just beneath it. It only takes a look, a smell or a moment on a bus and I am thrown back into the desperation of my boyhood in the Great Depression. When I drink a glass of milk it reminds me of all the mornings I trudged to school hungry and cold, waiting to fill my belly with the school’s milk rations for the desperate. Watching a teenager on a scooter reminds me of the fear and ecstasy I experienced in Britain during the Second World War. On cloudless days, I sometimes think I hear the murderous drone of V1 rockets as they swarmed towards London. When it rains in springtime, I remember again how at the end of the war the world smelled of petrol fumes and fresh flowers.

When I read newspaper reports of the corruption in Afghanistan – where the CIA and our secret service both act like patrons in a strip club with an unlimited expense account, and where untold and unaccounted-for money from the public purse arrives from the UK and US and disappears into the moral vacuum that is the Karzai government – I can’t help but think that it might as well be South Vietnam in the mid-70s, because it is going to end up that way when America and Britain disappear from the Great Game. When we are gone then the jackals known as the Taliban will descend from the mountains. They will enter the city gates of the ancient communities of Herat and Kabul. They will come as they always have in a shower of dust and Holy Scripture to terrorise a people whose only crime was to be born into a land that has been at eternal war since the days of Alexander the Great.

When I watch the beaming face of a British politician, telling me, telling Britain and telling the world that this island must decouple from Europe, that immigration is a grave concern; when I hear the familiar cadences of his xenophobia, I am reminded too much of another time when similar men spoke with more force and less nuance of a Britain for the British.

When there is a news story on Syria; when the video footage reveals a nation covered in blood, and a Middle East expert is interviewed and asserts with conviction that Assad is a war criminal while the rebels fighting him are a ragtag group who might be for democracy or they might be for the imposition of Sharia Law, I realise again that no one seems to know how it is all going to turn out. Somehow I suspect that whoever prevails, justice will not be top of their list. Instead, the victors will settle old scores as their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers did before them. The losers will get a bullet to the back of the head and a shallow grave in an ancient olive grove. I feel the same when I look towards Eastern Europe where the Ukraine – a traditional blood land for empires since the days of Genghis Khan – is now being drawn and quartered by Russia, the EU and America. None of these powers came to the Ukraine with good intentions. It is all about natural resources, spheres of influence and the caprice of oligarchs. Lives will be lost, hopes of democracy dashed, dreams of economic security crushed because while this fight may have been started by people who wanted better lives for themselves and their children, it has now been co-opted by the rich and powerful who are simply looking to increase their bottom line at the expense of honest and ordinary folk.

When I hear of payday loan sharks, of food banks, of housing shortages, of medicine as something you pay for or go without and of a decent education as something only for a certain sort, it is not shock I feel but a sense of recognition.

Nothing ever changes.

II. Yesterday’s men

I take my false teeth from their container and place them into my toothless mouth. I comb my hair with a brush that the RAF gave me during induction in 1941. Its bristles are still as strong as they were when they flattened the wavy locks of a boy of eighteen about to go to war. Yet looking at my sagging face, my white hair and my gnarled hands tells me what I already know. I am very old.

I fear death not because of what might await me on the other side. But I am nervous because I don’t yet want to put my hat and coat on and walk out the door. I don’t want to leave this world that I have lived in for almost a hundred years. It has given me an abundance of joy and of sorrow, and it is home.

Many of you, I am sure, consider me and those of my generation yesterday’s men, relics from long ago. But we are not so different to you. I still have many of your familiar worries, from how to pass the time of day to how to pay my rent. Like everyone else, I grumble about money. I think I have too little; that my pension is shrinking while the cost of living is rising. Like you, I have some regrets. Why didn’t I ever learn to swim or speak French? Why didn’t I buy that computer stock? Like all of us, I worry about my children, despite the fact that they are halfway along in their own lives.

Most questions about life remain unanswered for me. I still don’t know why our society favours some more than others. I am disgusted when I read about the bonuses doled out to banking executives as a reward for inflating their company’s stock value, or for washing the money of drug cartels with as much care as the Pope cleans the feet of the poor. It angers me to see a UK government minister boast that he could live on a welfare allotment of £53 a week when 300,000 citizens need to use food banks.

I will never understand why the daily rags castigate the poor and label them scroungers with a vigour that should be reserved for corporations like Google, Amazon, Starbucks and Apple who have wantonly taken advantage of loopholes in the law in order to avoid paying their fair share of taxes. I believe that those giant corporate monoliths treat their customers and the nations they do business in with contempt because they believe that their existence is of greater importance than the individual, the state or the laws that govern the rest of us. When a corporation can earn billions of pounds in profits but only pay several million in taxes, they cease to be of net benefit to society. Regardless of the fact that what they are doing is technically legal, no economist, politician or accountant can convince me that a company that hides its money offshore is anything but a buccaneer.

I have seen the smug faces of CEOs in Savile Row suits speak to gelded journalists on TV about ‘transparency’, ‘corporate governance’ and ‘fair play’, and know it is all spin. I am sure their sense of decency extends to their family, friends and allies – but the rest of us are just consumers that must be tolerated. The entitled believe they can buy a dispirited populace with words about corporate responsibility, but they cut wages, withhold benefits and reward loyalty with redundancies. And our politicians shake their hands as they do it.

The priorities of the government and the priorities of the people have not been as divergent since the early years of the last century. Eighty years ago Britain was in desperate straits. The Great Depression had shrivelled economic growth and caused widespread unemployment and untold misery to the working and middle classes. During those horrific times, another coalition government implemented austerity measures that caused millions of Britons to sink into unendurable poverty. It tore the country into two different tribes: the employed and the down-and-out. It took a world war, the wilderness years of post-war reconstruction and the erection of the welfare state to get Britain working again. Twenty-five years were lost; a generation sacrificed before our country returned to equitable prosperity for all of its citizens.

I have lived through it once, and I have seen the misery it produced. And yet today Cameron’s 21st-century government attacks this new recession with the same economic weapon used to battle the Great Depression in the 1930s. These men. They have the same suits, the same accents, the same smiles. Eighty years ago, cutting money for social services, housing and job creation was a grotesque failure. It didn’t succeed then and it is certainly not going to succeed today. My generation wanted action from their government but were ignored. In our present government I see the same reckless disregard for the eroding middle classes and the disadvantaged, the unemployed and underemployed. If history is our guide, it will take another lost generation before the United Kingdom can walk clear from this economic malaise.

But the soundbites are always the same. Britain cannot afford to protect its society – we are too much in debt; we have been too profligate with our money. Ministers speak as if the entire working and middle class have been on the piss for the past twenty years. Sometimes I think that those in power believe that since John Major left office in 1997 this country has been on an extended bank holiday.

British politicians are not alone in their obsession with government debt, slashing budgets and eradicating most of the testaments to the social welfare state. America, our great ally in the war, is also our greatest friend when it comes to championing the new theory that austerity is good for society, like bleeding a patient. Watch any interview and a senator from some great state or another will put the blame squarely on President Obama. If the president doesn’t fix the federal deficit, he whinges, hell and damnation wait for every American.

This senator is so caught up in his demagoguery that he forgets to mention, even in passing, that this present crisis – perhaps the greatest test of character to befall America since the crash of 1929 – might be the fault of a Republican government. The senator, like so many other people in America and Britain, has conveniently developed amnesia of George W. Bush and Tony Blair’s insistence that not one but two wars could be paid for like a flat-screen television with a payday loan. Yet this senator, along with the rest of the Republican party who clamoured for a war against Iraq in 2003 because Saddam supposedly had weapons of mass destruction pointed at our shores, has no difficulty stating that America is broke today because of the Democratic party’s largesse. According to him, the country just can’t afford to keep funding the lifestyle of its poorest citizens. To save the USA, according to the right-wing elites, the country’s underprivileged – those that are underemployed and a pay cheque away from homelessness – must never be allowed to reach a lifeboat.

The solution is simple for the senator – just cut the oxygen to social welfare programmes. Eradicate major funding for food stamps, tighten eligibility, and strangle the programme like a chicken. This is the current Republican strategy in the House of Representatives, where they are trying to remove 2 million men, women and children from being eligible to receive state-funded food assistance. The Republicans think that the poor of today should rummage through restaurant and grocery store rubbish bins if they are hungry, much like my own family was forced to do in Bradford in the 1930s when there was no social safety net.

Democrat or Republican? It doesn’t really matter, because those that hold the greatest power in American politics seem to feel that America’s decline is caused by the overreaching aspiration of the poor, the unemployed, the blue-collar workers, the unskilled and the ocean of undocumented illegal immigrants. The majority of decision-makers don’t see that the problem with America is not its average citizen but the proverbial cream at the top, whose corporate donors and hired lobbyists perpetuate a society where the minority are granted outrageous entitlements and the cost is borne by a disenfranchised middle class.

The free world used to say that the US was the birthplace of modern democracy and innovation. Not any more. I am terrified by the wind that guides America’s ship of state because she is sailing further and further into a blustering storm of jingoism. Many once espoused America to be the greatest nation on earth, but she is now as ambitious and forward-thinking as the Ottoman Empire in 1917. Today, America is a nation more at ease with stripping away the ancient rights of its citizens and workers rather than protecting them. Twenty-four US states have now enacted right-to-work legislation that dilutes the power of unions to negotiate for its members. Moreover, several states and many cities have enacted bills to remove the collective bargaining rights of workers.