6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Winner--Best Biography/Memoir of 2002, Midwest Book Awards (St. Paul, MN)

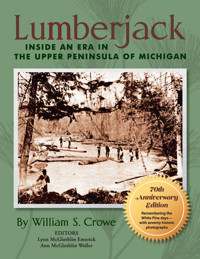

Lumberjack is a firsthand account of the lumbering era during the white pine boom years of the late 1800s - early 1900s in the northern U.S. Millions of board feet of logs were cut in deep woods camps, driven down the rivers to the sawmills, and shipped by schooner and barge to build a nation. This edition includes 78 historical photographs and illustrations, a glossary, editors' notes, maps, and much more.

"The lumber barons, the lumberjacks, and the town people who worked in the mills--as well as the happenings of that period... are recalled by one who lived among them. I hope it will be an inspiration to others to set down their memories of the days of falling pine and belt-driven sawmills. Already too much of this story has passed beyond recall... a valuable addition not only to the history of Manistique, but to the state as well."

--Ferris E. Lewis, Michigan History, Lansing

"An authentic first-hand account... which tells the whole story of big-scale lumbering during the 1890s and early 1900s. Chapter by enthralling chapter, Crowe recounts the times involved in the 'big pine' operations... it rivals anything so far written... rich in description and alive with thrilling episodes."

--Marquette Mining Journal

"First-hand accounts of the dramatic 'big cut' by participant-observers are always illuminating. William S. Crowe's reminiscence of his years in the woods and the early days of Manistique, at the north end of Lake Michigan in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, was a classic in the 1950s. His granddaughters Lynn McGlothin Emerick and Ann McGlothin Weller have done a real service by republishing his book with ample photos and notes."

-- Mary Hoffman Hunt, Midwestern Guides

"Focusing on Manistique and meticulously researched, Lumberjack explores the early days of logging and the lifestyles of the countless loggers that filled the woods in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. William Crowe, the author, was a logger himself who collected and relates real stories from the men who were there. This is a mandatory book for anyone interested in the history of the Upper Peninsula."

--Mikel B. Classen, author/historian, True Tales: The Forgotten History of the U.P. and Faces Places & Days Gone By: A Pictorial History of the U.P.

From Modern History Press

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

© 2002 Lynn McGlothlin Emerick & Ann McGlothlin Weller

Third Edition

All rights reserved

ISBN 096-50577-3-9

Library of Congress Control Number 2002104698

Published by North Country Publishing

355 Heidtman Road • Skandia, MI 49885

(906) 942-7898

Toll free: 1-866-942-7898

Printed in the United States of America

Photographic Reproduction—Photomaster, Marquette, MI

and the State Archives of Michigan, Lansing, MI

Book and Cover Design—Holly Miller, Salt River Graphics, Shepherd, MI

Illustrations—Carolyn Damstra, East Lansing, MI

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used, reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or information storage and retrieval, without written permission from the editors, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, on-line review site or broadcast.

In memory of

William Scott Crowe, our grandfather, who lived it,

Helen Crowe McGlothlin, our mother, who kept her promise,

and for Stephen, Lynn, Mary and Susan,

the next generation

The stories and experiences of our grandfather, William S. Crowe, along with his efforts and those of our mother to create the First and Second Editions of Lumberjack, have long been a part of our remembrances.

The Golden Anniversary year of the original publication of these stories seemed an appropriate time to bring Lumberjack back into circulation. Crowe’s experiences over a century ago in the north woods of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan provide a vivid link to those times for a new generation of readers.

Contents

Preface

ONE Lumbering Towns and Company Men

TWO At the Sawmills: Cribs, Yards, Office

THREE The Waterfront

FOUR The River and the Woods

FIVE Kerosene Days

SIX The Froth and the Truth

SEVEN Buying the Chicago Lumbering Company

EIGHT Peace, Progress and Prosperity

Biography: William S. Crowe

Editors’ Notes

Glossary

Acknowledgments

Credit: Front and Back Cover Photographs

About the Editors

Map: The Upper Peninsula of Michigan

PREFACE

The History of Lumberjack—Inside an Era

In his Introduction to the First Edition, published in 1952, the author, William S. Crowe, explained how Lumberjack came to be:

In the fall of 1947 several letters appeared in the Escanaba Daily Press speculating on the identity and meaning of certain “mysterious” marks found on lumber used in construction of the Schoolcraft County Memorial Hospital at Manistique, various theories being advanced ranging from Egyptian hieroglyphics to the American Indians. The lumber had been sawed from “deadhead” logs that had been submerged in the Manistique River for fifty years or more, and then salvaged by a local sawmill.

It seemed incredible to me that there should be any mystery about the origin and purpose of these marks, as I supposed everyone was familiar with the system of log marking used in the old pine lumber days. I suddenly realized that a colorful era which seems only yesterday to me ended half a century ago and that few of the present generation have ever seen a big sawmill, or even a really big pine tree.

Furthermore, this half century of American history witnessed changes of kaleidoscopic rapidity far beyond any similar period prior to the American Revolution.

The marks in question were very familiar to me because part of my job with the Chicago Lumbering Company was to keep a tally of them, so I consented to write a few articles descriptive of those times.

Here and there some digressions into the general field of economics, which some may think foreign to the title, are only intended to give a clearer overall perspective of life in those days. It would be hard to understand the lumberjacks and their actions and ways of life without some knowledge of the background and a general picture of actual life at that time.

However, I have tried to confine my digressions to only those phases that have a direct bearing on the life of the lumberjack and the White Pine era.

I am not a professional writer, and if the personal pronoun crops up too often, my apology is that this is simply a story told in as simple language as possible about matters and events in which I was either an active participant or a firsthand observer. This gave me one advantage over certain professional writers who depended largely on hearsay. I was able to screen out the “chaff” from the Bunyanesque tales with which the lumberjacks delighted to regale their listeners, and I can therefore guarantee the reliability of what little hearsay does appear in these articles.

Wm. S. Crowe

FIRST EDITION—1952

Crowe’s articles, published in the Escanaba Daily Press and the Manistique Pioneer-Tribune at various times during the 1930s and 1940s, aroused much interest in the history of the area and region and he was urged to publish a book of his experiences. One day, Mr. Harold “Rabb” Klagstad, a former Manistique resident and partner in and head of the Chicago branch of Ernst and Ernst (a nationally known accounting firm), asked me to put these articles together in a book. I told him that writing a book and publishing a few letters of local interest were vastly different propositions but he said if I would give him copies of the letters, his firm would print the book, provided I would give him copies to distribute to colleagues and friends. That is how the book came to be written.1 The very small print run of Lumberjack soon sold out.

SECOND EDITION—1977

The response to the First Edition of Lumberjack, and the many requests for copies which could not be filled, encouraged Crowe to begin preparations for an expanded Second Edition. He collected photographs, conducted research, planned trips to the West Coast and contacted key informants throughout the next decade.

I can now give attention to completing in real earnest the second edition of the booklet. Lumberjack…. it will be a book of reference, and historical fact, but interspersed with anecdotes and personal stories so as to make it interesting as general reading for the public.

The purpose will be to make it a real picture of actual life in those days with mention of many things considered too unimportant by professional writers but which together give a mental picture of the way people actually lived in those days. The new edition will contain everything in the first edition and a lot more in the way of pictures, maps, and detailed information about 100 million feet of “big pine” every year from the “stump” to the decks of the lumber schooners and lake barges for shipment to Tonawanda, Chicago and other ports. The object is not only to give a true picture of the lumberjack and his habits, but also to recreate the atmosphere of those old days and the background of the times in which he lived.2

In September 1965, William Crowe fell ill and died six weeks later. In an article upon publication of the Second Edition, his daughter, Helen Crowe McGlothlin, said, “From his hospital bed, he looked at me and said, ‘You’ll get my book published, won’t you?’ And I said, ‘Well, yes.’”

It took her twelve years to keep her promise, but in 1977, twenty-five years after the original book, an expanded version of Lumberjack was released. Ted Bays of Bay de Noc Community College edited Crowe’s thirty-two articles into eight chapters; Helen McGlothlin added many new photographs from Crowe’s collection. The Second Edition was printed and published by Frank Senger of Senger Publishing Company, Manistique; the Second Edition has also long been out of print.

THIRD EDITION: 2002

As co-editors of this new Fiftieth Anniversary edition, we have honored William Crowe’s story as he lived it and wrote it.

Where new information has been included in the text, it has come directly from his own letters, notes and published writings. Where clarifications or expansion of information have been made, they are provided in an Editors’ Notes section and referenced by number within Crowe’s text. Terms of lumbering and social custom used in Lumberjack are defined in an expanded, illustrated Glossary. The sources from which relevant information was obtained are referenced in these two sections.

More than forty historic photographs of life and logging in the white pine days have been added to the Third Edition. As in the Second Edition, some chapter titles and subtitles have been changed or added to reflect more accurately the content within.

Friends, relatives, new acquaintances and staff members of various organizations have been generous in their encouragement, searching for information, dates, historic photographs and little-known or forgotten facts in answer to questions and missing pieces of the puzzle. An Acknowledgments section recognizes those who have assisted with this and previous editions of Lumberjack.

William S. Crowe “lived in interesting times” and his life story highlights the building of a country as well as the remarkable experiences of many young men and women of his era. From his papers and those of his extended family, we have developed a biography of William S. Crowe, with selected photographs, and included it in this edition.

Our grandfather’s stories, and the life he lived so long ago, have come alive again for us as we reread his correspondence, followed his hopes for his writings, researched obscure references and old publications, delved into log marks and river driving, viewed photographs and maps of that era and shepherded this new edition of Lumberjack to life.

Lynn (Crowe) McGlothlin Emerick

Emerick Consulting

Marquette, Michigan

Ann McGlothlin Weller

Services for Publishers

Holland, Michigan

May 29, 2002

1WSC letter to Mrs. Clifford Crick, July 7, 1961.

2WSC preliminary memo for letter to Timothy Pfeiffer, November 22, 1957; general memo, October 1, 1962; letter to Miss Dorothy V. Weston, May 20, 1963; and letter to L. G. Sorden, July 13, 1963.

Mature eastern white pines on the Menominee Indian reservation. In much of the Northern Great Lakes region—Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota—the trees grew close together and often over 100 feet tall. In the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, there are white pine groves remaining in the Estivant Pines Nature Sanctuary, Keweenaw County; Laughing Whitefish State Scenic Site, Alger County; and Sylvania Wilderness Area, Gogebic County.

CHAPTER ONE

Lumbering Towns and Company Men

he identity of the mysterious marks found on lumber sawed from deadhead logs was quite clear to me because I was once head bookkeeper for the Chicago Lumbering Company of Michigan (C. L. Co.) and the Weston Lumber Company (W. L. Co.), and have lived in Manistique for over seventy years.

Since Manistique, like many other towns in Michigan during the colorful white pine days, was an almost one hundred percent pure lumber town, the story is mostly about lumberjacks, woods, big sawmills and lake shipping. As bookkeeper for one of the largest lumber companies during the seven years when the industry was at its peak, I had splendid opportunity for firsthand observation.

When it comes to a matter of detail and recreating the atmosphere of those days, the stories of the other lumber towns of Michigan are exactly the same as Manistique; residents lived their daily lives as we did here. The faces changed and the proprietors, the “Lumber Barons,” were all different, but lumbering was the same.

“There is no other tree in all the world which has so much of romance … as the white pine.”

There is no other tree in all the world which has so much of romance, and was so closely associated with people’s daily lives and manner of living, as the white pine, which is now almost extinct except for some tracts of closely related sugar pine on the west coast.

And I believe there were no more colorful or interesting or exciting segments of American life than the lumber industries, nor a more picturesque individual than the old-time lumberjack and river driver. They were in direct contact and conflict with Mother Nature in the raw—a comparable industry in this respect being the cattle ranches of the great plains and the western cowboy. I lived for two years on a cattle ranch in Colorado before coming to Michigan so I had good opportunities to get first-hand impressions of both the lumberjack and the western cow-puncher.

A more completely different stage, background and environment could hardly be imagined than the immense pine forests and the treeless, seemingly endless plain, nor two more different individuals than the lumberjack and the cowboy. A cowboy would have been lost almost at once in the great pine forests, and a lumberjack would have been lost even more quickly on rolling treeless plains.

Log marks from Upper Peninsula lumber companies: (1) Goodenough & Hinds, Delta County, 1889; (2) Garth Lumber Co., Delta County, 1894 (also used by Weston Lumber Co., Schoolcraft County); (3) Charles Mann, Delta County, 1902; (4) J. A. Jamieson & Co., Mackinac County, 1908; (5) Marsh, Koehn & Co., Menominee Count)’, 1904; (6) Oliver Iron Mining Co., Menominee County, 1938; (7) McMillan Bros., Ontonagon County, 1902.

But although environments and ways of life differ, people are fundamentally about the same wherever you find them, and the cowboys and the lumberjacks had the same spirit of daring, resourcefulness, initiative, independence and romance bred by close contact with nature at her best and worst in a vast, free country.

One thing common to cowboy and lumberjack was the similarity of the cattle brands and log marks. The W. L. Co.’s “Barred O” and “Circle 0” were duplicated on the cattle ranges, and a big western ranch’s “Cobhouse” brand was exactly the same as the C. L. Co’s “Cobhouse” log mark.

The quadruple cross was the familiar C. L. Co. “Cobhouse,” and the cross in a circle was the W. L. Co’s “Barred O” . These marks and the Weston Lumber Company’s “Circle O” accounted for about ninety percent of the roughly four billion feet of white pine and red, or Norway, pine these companies cut in their forty-one years of operations, 1872-1912.1,2

Other marks which frequently came up C. L. and W. L. jack ladders were Hall & Buell’s , the Delta Lumber Company’s triangle , JDW logs cut from J. D. Weston land, Edward Hines & Company and the marks of Alger, Smith and Co. , which operated a big mill at Grand Marais supplied by their own railroad to Seney, Germfask and Curtis. The C. L. Co., with a branch office at Seney, operated in that territory at the same time and sometimes cut isolated forties for Alger, Smith and Co. and ran the logs to Manistique in their main river drive.

A single company might have more than one hundred log marks. Delta County in the Upper Peninsula received so many registrations that the Log Mark sheet was developed for recording purposes.

General Russell A. Alger, President William McKinley’s Secretary of War, was the principal stockholder in Alger, Smith and he and Abijah Weston were great friends.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Hall & Buell had a large sawmill at South Manistique. a community of about 1,200 people on Lake Michigan one mile southwest of Manistique. Not a vestige of South Manistique remains except part of Hall & Buell’s old log pond. Their mill was supplied by a railroad from their Indian Lake pull-up and from another pull-up on the Manistique River just above the C. L. Co.’s dump. When the C. L. Co. built the Manistique and Northwestern Railway (now part of the Ann Arbor system) to Steuben and Shingleton in 1896, they bought Hall & Buell’s railroad to have access across the Soo Line.3

The Delta Lumber Company had a sawmill at Thompson (population about 500 in 1893) supplied by a railroad from a pull-up on the Indian River north of the Big Spring, with branches here and there on the plains between Indian Lake and Cooks west of Delta Junction. A railroad along Lake Michigan connected Thompson with South Manistique and Manistique. The combined population of the three communities in the 1890s was about 5,500.

All told there were over twenty log marks, and a scaler at the head of the jack ladder in each of the five mills entered the scale of every log under its particular mark on a scale sheet. The C. L. and W. L. companies used the combination Doyle-Scribner rule: Doyle for small logs up to twenty-eight inches in diameter, and Scribner for large logs over twenty-eight inches. The mill lumber scale usually was higher than the log scale from ten to thirty percent. In 1913 the lumber scale overran the log scale almost exactly thirty percent.

Manistique Harbor in the early days.

A NEW DAWN

When I landed at Manistique from the Goodrich Line’s City of Ludington at exactly midnight, May 29, 1893, I stepped into a strange new world such as I had never seen or even dreamed of. I was only seventeen and had lived for two years on a cattle ranch on the treeless plains of eastern Colorado northeast of Fort Lupton. I had never seen a ship, a large body of water, a sawmill or even a big tree. The screaming saws in five big mills, running twenty-four hours a day; the scent of new lumber and the pine woods; the hoarse whistles of lake steamers; the tall masts of lumber schooners in the harbor; and the flickering flames and red glow from the open burners reflected across the water and in the sky against the dark and somber background of the immense forest—all gave me a feeling early pioneers must have experienced when they discovered a new and unexplored area. I could hardly wait for morning to dawn.

Chicago Lumbering Company saw mills and lumber yards at Manistique.

The Chicago Lumbering Company of Michigan was organized in the summer of 1863 by certain Chicago interests who operated a small mill with two circular saws and one gang saw until 1871, when Abijah Weston and Alanson J. Fox came up from Painted Post, New York, and bought the company. From that time until December 1912, when Mr. Lou Yalomstein (then manager of the C. L. Store) and I organized the Consolidated Lumber Company and purchased all their properties, the Chicago Lumbering Company of Michigan and the Weston Lumber Company (they had the same stockholders) were the whole thing in Manistique and Schoolcraft County. The C. L. and W. L. companies owned at this time all of Schoolcraft County, parts of Delta and Mackinac counties and all of Manistique except the wooden saloons in the Flatiron block on Pearl Street, schools, churches and six or seven stores on Cedar and Oak Streets.4

The board of directors of the Chicago Lumbering Company of Michigan and Weston Lumber Company. Standing, left to right: William H. Hill, William E. Wheeler, John D. Mesereau, N. P. Wheeler. Seated: George H. Orr, Alanson J. Fox, Abijah Weston, M. H. Quick.

Abijah Weston, Fox and their associates were very wealthy men, and when they took over in 1871 things commenced to hum in Manistique.5 In 1893 when I started to work as time boy, they were operating three large mills, a planing mill, a charcoal iron furnace and about twenty-six other departments that covered almost every activity found in a community of four thousand people. They employed about twelve hundred men then and I became well acquainted with their various managers and foremen, including: John Quick, C. L. Mill; W. C. Bronson, W. L. Mill No. 1; Sam Mix, W. L. Mill No. 2; John Woodruff, C. L. Lath Mill; E. A. Rose, W. L. No. 2 Lath Mill; R. B. Waddell, Weston Mfg. Co. Planing Mill; H. Duval, Weston Furnace Co.; Arthur DuBois, Manistique Telephone Co.; C. P. Hill, C. L. Store; I. S. Phippeny, W. L. Store; E. W. Miller, Warehouses and Docks; Capt. Lossing, C. L. Dredge; Capt. John McWilliams, Tug Elmer; R. P. Foley, Ossawinamakee Hotel; George Wickwire, Retail Lumber; Frank Havilchek, C. L. Machine Shop; A. D. McNair and J. A. Hamill, C. L. Blacksmith; Fred Denzeng, C. L. Harness; Abner Orr, C. L. Barn; M. W. Cutler, W. L. Barn; E. C. Brown, Shipping & Yards; C. J. Thoenen, C. L. Hardware and W. F. Kefauver, C. L. Furniture and Undertaking (on a leaf from the Ossawinamakee Hotel6 Register dated June 19, 1894, appears the following advertisement: “Chicago Lumbering Co. of Michigan, Undertaking.”) The company’s furniture and undertaking parlors were located in a building opposite the Elks’ Temple, where the Tribune Publishing Co. now stands. H. W. Clarke was cashier of the company’s Manistique Bank. Even the cemetery and the post office were company departments for many years, and the village president, clerk and treasurer were usually one or other of the company’s officers.

The Weston Lumber Company’s “new mill,” under construction on the west side of the Manistique River in 1884.

J. D. Mersereau, Secretary and Treasurer in charge of the General Office; M. H. Quick, General Superintendent of the Mills and Yards; and George H. Orr, General Woods Superintendent, were all stockholders in both companies. Ed Cookson was walking boss in the woods under Mr. Orr, and prominent camp foremen and jobbers were Frank Cookson, George L. Hovey, “Red Jack” Smith, C. O. Bridges, Paddy Miles, George Scott, Murdoch McNeil, George Roberts, Dugald McGregor, Peter McGregor, William Clemons, the Ferguson brothers of Munising, Bill Lockwood and a number of others.

Abijah Weston, who owned fifty-one percent of the stock in both companies, also had interests in Buffalo, Niagara Falls and elsewhere, including banks, lake shipping and a sizable distributing yard at North Tonawanda, then the largest lumber distributing point in the United States. I estimated his wealth to be somewhere between $30 and $40 million. He died in March 1898.

The combined capital of the two companies in 1894 was $2.1 million (Old Deal dollars, which in terms of today’s [late 1940s - early 1950s] depreciated gold dollars and inflated credit money and prices would be about $25 million) and their operations were on a larger scale than most of us today realize. The flagship of the TBL (Tonawanda Barge Line) fleet of lake steamers and barges owned by A. Weston & Son carried about one million feet of lumber, and I used to make out bills for cargo after cargo, not one of them over $15,000; on today’s market they would all be worth at least $350,000. In the railroad panic of 1893 the two companies lost approximately $1.5 million, but in one seven-year period with which I am familiar (1893-1900) they paid $8 million in cash dividends.

The Chicago Lumbering Company was said to be the most efficient pine lumber company ever to operate in Michigan—a very broad statement indeed. I think it was true for the following reasons:

• The owners were experienced lumbermen who had made fortunes lumbering in New York and Pennsylvania before they came to Michigan.

• From 1871 until the 1890s, Manistique and Schoolcraft County were isolated in winter from the outside world except for weekly mail brought from Escanaba over the ice, usually by an Indian, to Fayette and from Fayette to Manistique by snowshoe courier. After the Detroit, Mackinac & Marquette Railroad, now the DSS&A (Duluth, South Shore & Atlantic Railway) was built, the mail was brought by stage down from Shingleton. In summer, access was by lake boats.

• George H. Orr, General Woods Superintendent, and M. H. Quick, Superintendent of the Mills, Yards and City Property, knew from personal experience the exact requirements of every man’s job and how it should be done. There wasn’t a trace of high hat and any employee could talk to the bosses anytime as man to man.

The result was a close-knit organization which operated in complete harmony for over forty years, just like a big family, with no change at all in management and almost no labor turnover. Many of the men worked for the company for their entire lives and became experts in their jobs, especially in the woods. In the rare cases when a lumberjack sought a job outside, he only needed to show that he had worked satisfactorily for the C. L. Company.

The seven Orr brothers, pioneers prominent in Manistique history for a half century. Standing, left to right: Fred, Walter, Burton, Erastus. Seated: Aaron, Abner, George H.

C. L. Company’s “Mud Hen” paddle-wheeler used for rafting and booming logs on Indian Lake in the 1880s and 1890s.

George “G. H.” Orr was Woods Superintendent for the C. L. and W. L. companies for forty years, and President of the C. L. Co. The Orr Bros, partnership—Erastus. Burton and Walter, along with Ed Brown—built the Orr block and had a meat business, cattle ranch and slaughter house. Fred Orr was sheriff for four years,7 a busy office in those days, and Walter was village president at a time when the caucus resembled a three-ring circus or battle royale. Abner Orr, barn boss, had charge of the C. L. Barn, the Indian Lake Farm and about three hundred heavy draft horses. There was no nepotism. If anything, the Orr brothers were tougher in business dealings among themselves than with others.

George H. Orr came to Manistique with his family on the schooner Express in 1872 and contracted to put in logs for Weston on Murphy Creek. He did so well and made so much money that Weston bought up his contract, gave him a five percent stock interest in the C. L. and W. L. companies and made him General Woods Superintendent. In later years he was made President of the C. L. Co., an office he held until his death in 1912. His five percent stock interest in the W. L. Co. made him a millionaire.

During the forty-two years the companies operated, their mills never lost one minute’s time for log shortage. There were always logs—usually a reserve in the rivers that was sufficient to run the mills for a whole season.

The first Sunday I was in Manistique, John Woodruff and I hiked out to Indian Lake and then walked across on the big pine logs that filled more than half the lake (the company’s old tug, as big as a house, was out beyond the logs)8 to the present golf course—then part of the company’s Indian Lake Farm—to see the horses. There were over 275 big heavy draft horses out for summer pasture, any one of them fit for a ribbon at a horse show. I had seen plenty of horses on the western cattle ranges, but nothing like these As I walked among them, now and then one would raise its head, look mildly at us for a few seconds and then calmly resume grazing. They evidently decided we were harmless creatures of little importance.

Mr. Orr once told me that “some horses have more sense than some men,” and I thought of a certain farmer on the river road who sometimes got well pickled when he came to town; later, friends would load him, in an unconscious stupor, into his wagon or sleigh and unhitch and start the horses. The horses never failed to take him home, where they would stand and wait patiently until relieved.

George Orr was a great lover of horses and a good judge of horseflesh. He had a fast-stepping little mare and a light cutter for his camp inspection trips, and foremen said they liked to watch him speeding along, horseshoes clip-clopping and sleigh bells jingling, over the wide icy log roads, smooth as a boulevard, winding in and out among the trees. He would inspect the horse barn first, and the surest way for a foreman or teamster to get in bad with him was to mistreat a horse.

John Creighton was a tote teamster for the C. L. Co. for nine years. He was an expert horseman in whom George Orr had a lot of confidence, and on one of his horse buying trips outside he took Creighton along. On his trips to and from camp Creighton would shoot deer. The camp bought all he shot on the way up to camp for $2 a head, and the deer he killed on the way back he sold in town at $3 a head. I was told he shot forty-nine deer one fall on these trips. His rule was, “one cartridge, one deer,” and he never took a chance of wasting a shot or wounding a deer that was too far away for a sure shot. In those days there were no game laws, deer were very plentiful, the “sportsmen” hadn’t yet arrived on the scene and lumbermen and the Indians killed only what they needed for meat. Many of the camps had a camp hunter to keep them supplied with meat. George Hovey told me that the hunter for the C. L. Company’s camp on Doe Lake killed over seventy-five deer one winter without having to leave the camp. There are probably five times as many deer killed or wounded in the deer season today as there were then, and back then we never heard of men, cows and horses being shot and killed because someone thought what they saw was a deer.

M. H. Quick was a millwright and saw filer for Weston for years before he came to Manistique in 1872 to become General Superintendent of the Mills, Yards and City Property, continuing until the company sold out in 1913. He was also one of the officers of the company, in which he had a ten percent stock interest.

When two men can direct the operations of a big company for over forty years, with stockholders and directors in complete agreement and with practically no labor turnover, it is certain that both management and men had to be just about tops. Mr. Orr had twenty or twenty-five of the best camp foremen in the country, and Mr. Quick’s mill and yard foremen and crews were organized to the last detail.

Further proof of the company’s efficiency is the fact that they delivered millions of feet of clear white and red pine lumber on the boats at an overall cost of $9 to $12 per M, including stumpage. White pine stumpage was figured at $3 and the mill rate for custom sawing other companies’ logs that happened to go through the mills was also $3. On those prices, the company made a profit.

CAMP TALES

Frank Cookson was one of George Orr’s most efficient camp foremen and rivermen. The story is told that Cookson bet he could cut a log in the woods, carry it to the river and ride it across without getting wet, and when someone took him up on it, he cut a dry cedar about twenty-five feet long, carried it to the bank and not only rode it across the river, but lay down on his back and smoked a cigar while doing it. Some doubt that, but I knew Cookson pretty well and I believe it. I know he could easily have carried a dead cedar log big enough to float him, and there were dozens of river drivers in the C. L. crews who could ride and birl logs and perform stunts better than many professionals I have seen. The Knuth boys were especially good.

Cookson and I once went up to inspect and check George Roberts’ operations. Roberts had finished a large cedar contract on the Upper West Branch of the Manistique River. We went to Shingleton on the Haywire9 and from there walked on snowshoes over seven miles, arriving at his No. 1 camp about dark. All the camp watchman had to offer were some mouldy biscuits, cold soggy boiled potatoes that had began to spoil and fat salt pork—“sow belly”—without a streak of lean in it. We made tea and fried some of the potatoes which helped a little, but Cookson told me afterward it was the worst meal he had ever eaten. As for me, however, after a seven-mile hike on snowshoes I had the appetite of a goat. We spent the next day inspecting Roberts’ cuttings, which covered six sections, and then hiked back to Shingleton the same night.

For me, that was a journey into the never-never, a giant’s fairyland. The deep snow clung in the most unbelievable shapes to the stumps and tangled slashings; odd and misshapen tree trunks leaned at all angles; blackened ghostlike stubs from old forest fires and living green cedars all mingled in the utmost confusion to create a perfect foundation for the snow to form a fantastic wonderland.

A “stump mushroom” of snow stands tall in the deep woods of Ontonagon County.

There were caverns, tunnels, bridges, steeples, castles, draperies and lace curtains, and shapes no description would fit, and everywhere the gigantic toadstools—enormous snow caps on the stumps. One on an eighteen-inch stem measured eight feet across. The absolute silence and dead stillness was without a sign of life and these grotesque and monstrous shapes in the dim twilight were almost frightening but from another angle the unearthly beauty of the scene in the ghostly moonlight, with the Northern Lights flickering overhead, surpassed all imagination. Even Cookson, a practical man familiar with woods scenes, remarked about it.

A winter trip in the Carp River valley, Marquette County, 1890s.

That night I dreamed I was a pygmy lost in a wilderness of giant toadstools peopled with tall black monsters reaching for me with long arms. The dinner probably had something to do with my dreams.