Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

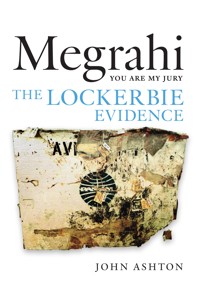

'You know me as the Lockerbie bomber. I know that I'm innocent. Here, for the first time, is my true story: how I came to be blamed for Britain's worst mass murder, my nightmare decade in prison and the truth about my controversial release. Please read it and decide for yourself. You are now my jury'. (Abdelbaset al-Megrahi). For the first time the man known as 'the Lockerbie bomber' tells his story. This long-awaited book argues that, far from being an unrepentant terrorist, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was the innocent victim of dirty politics, a flawed investigation and judicial folly. Based on exclusive interviews with Megrahi himself, and conclusive new evidence, it destroys the prosecution case and puts the Scottish criminal justice system in the dock. Megrahi: You Are My Jury makes a compelling argument that the murderers of the 270 Lockerbie victims were acting on behalf of an entirely different government, rather than Colonel Gadafy and Libya.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 959

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Megrahi

YOU ARE MY JURY

____

THELOCKERBIEEVIDENCE

John Ashton is a writer, researcher and TV producer. He has studied the Lockerbie case for 18 years and from 2006 to 2009 was a researcher with Megrahi’s legal team. His other books include What Everyone in Britain Should Know about Crime and Punishment (with David Wilson) and What Everyone in Britain Should Know about the Police (with David Wilson and Douglas Sharp), both published by Blackstone Press.

First published in 2012 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and John Ashton, 2012

The moral right of John Ashton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher

eBook ISBN-13: 978 0 85790 232 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

List of plates

Preface

Acknowledgements

1 The World’s Most Wanted Man

2 Before the Nightmare

3 Pan Am 103

4 The Double Agent

5 The Shopkeeper

6 The Suitcase

7 The Fantasist

8 The Experts

9 Target Libya

10 HMP Zeist

11 Trial and Error

12 The Bar-L

13 The Truth Emerges

14 A Death Sentence

15 The Real Story of Lockerbie

Appendix 1 Gauci’s Police Statements

Appendix 2 Primary Suitcase Forensic Evidence

Appendix 3 The Frankfurt Documents

Appendix 4 Justice Delayed

Afterword

Footnotes

Notes on the Text

Glossary and Abbreviations

People Mentioned in the Text

Index

Plates

The wrecked cockpit of Pan Am 103, Maid of the Seas

Luggage container from Pan Am 103

How the primary suitcase may have been loaded

Toshiba RT-SF16 radio-cassette player

Mock-up radio-cassette bomb

MST-13 timer

Circuit-board fragment PT/35B

PT/35B matched to control sample

Abdelbaset’s student identity card

The photospread shown to Tony Gauci more than two years after Lockerbie

Telexes sent to and from Abdelbaset when with ABH

US government reward poster

Extracts from Tony Gauci’s first statement to police

Edwin Bollier in the early 1970s

Extract from a CIA cable concerning Majid Giaka

Hafez Dalkamoni, leader of the PFLP-GC’s West German cell

PFLP-GC bomb-maker Marwan Khreesat

Mohamed Abu Talb, the Swedish-based terrorist

Abdelbaset and John Ashton

Abdelbaset and Nelson Mandela

Inscription written by Mandela in Abdelbaset’s copy of Long Walk to Freedom

Preface

‘We all know he didn’t do it.’

The words of one of the friendly prison officers who, every few weeks, would usher me into a tiny room at Greenock prison, where I would meet Britain’s supposed worst mass murderer. We knew him as Baset; to the uninformed he was the Lockerbie Bomber.

A few minutes later I would hear a door unlock and the familiar quiet voice greet the officers with, ‘Good morning gentlemen’. Then Baset would enter the room, shake my hand and sit down facing me across a small table. Invariably he would have with him a bundle of papers, the very same documents that, a few years earlier, had been used to convict him.

He had employed me as a researcher to work alongside the lawyers who were battling to overturn that conviction. He would take me through fine points of detail and I would update him on my work. He was demanding, but unfailingly polite, his frustration at his plight never sublimated into anger. He had scoured every last page. He felt he had no option. Why, after all, should he trust us when we were part of a justice system that had failed so catastrophically?

We were allowed two and a half hours together. Once we’d talked detail, the conversation usually turned to the injustice itself. The same questions always recurred. Why had certain witnesses changed their stories? How could the Crown justify withholding vital evidence? And, most importantly, how could three learned judges have reached such a perverse verdict? We had no answers.

When our time was up, Baset was escorted to his wing to resume prison life. Walking back to the railway station, it was almost impossible to imagine his daily reality. It was rather easier to daydream. I fantasised, childishly, about the day he would walk free from court and be reunited with his family. We had a strong case – the most spectacular appeal victory in memory was within our reach. And yet, after two years of visits, we were still having the same conversations and were still nowhere close to starting the appeal. The system had failed him again, this time through inertia, rather than misjudgement.

In September 2008 came the terrible news that Baset had aggressive and incurable cancer. The psychological pain which, for years, had consumed him now had a physical manifestation. Those who had called for the death penalty had got their way.

A couple of weeks later he asked to see me again. He told me he wanted to tell his story in a book and needed me to write it. He knew he would never live to see the conviction overturned, but he wanted the public to know he was innocent. I wanted to make a start immediately, but he was, understandably, too distracted by his plight to help me.

It was not until almost a year later that I got under way. By then his dream of freedom had finally been realised. In other ways, though, he remained trapped in a nightmare. Not only was he terminally ill, but in the eyes of the law, he remained guilty of one of the worst acts of terrorism ever committed. In order to secure his release he had abandoned his appeal against that guilty verdict. It was a terrible choice to have to make, as he never doubted that, if they considered the evidence objectively, the appeal judges would overturn the conviction. From the moment he made that decision, he was determined that, if he could not be judged in a court of law, then he should be judged in the court of public opinion.

I had to make numerous trips to Tripoli, where I visited him at his suburban home. Although now free, he was no less eager to set the record straight and ensure that I had every fact correct. Once again my visiting hours were restricted, not by prison rules this time, but by his pain and tiredness. Back among his beloved family, he no longer wore the strained look I had witnessed in Scotland, but our conversation was, nevertheless, punctuated by the savage symptoms of his illness.

The book tells two stories. The first is Abdelbaset’s: of his life before 14 November 1991, when, out of the blue, he was charged with the bombing; and of the 20 years of suffering that he and his family have endured since then. The account is based on the numerous interviews that I conducted in Tripoli and on our informal prison conversations. With his agreement, I wove them together with his previous legal interviews to create a first-hand account, which appears in italics. It is by no means complete; in particular it contains little about his emotional state at key moments in the drama of the last two decades. He has always focused on facts rather than feelings, and, perhaps typically for his generation, he is not at ease with public expression of private emotion.

The second story is that of the bombing itself and the subsequent international investigation. It also recounts the evidence that would have been heard at Abdelbaset’s appeal. It argues that Abdelbaset and the Libyan people suffered a grave injustice. The Gadafy regime was responsible for many appalling crimes, its brutal response to the February 2011 uprising only the latest. Lockerbie, however, was almost certainly not among them. There is no more reliable evidence of its involvement than there is of Saddam Hussein’s involvement in the 9/11 attacks. No one will shed a tear that Gadafy was wrongly accused; what made this miscarriage of justice so uniquely appalling was that it was suffered by an entire nation. Libya endured 12 years of UN sanctions, predicated on paper-thin evidence, some of it concocted. By surrendering themselves for trial, Abdelbaset and his co-accused, Lamin Fhimah, removed the country from that headlock. Small wonder that each received a hero’s welcome on his return to Tripoli.

Both stories are, at times, complicated and involve a large cast of players. To help readers navigate, I have provided a glossary and notes on some of the more important people and organisations at the back of the book (see pp. 472 and 476).

Abdelbaset insisted on checking the manuscript for accuracy, but gave me the final say on its contents. He did, however, demand that I make three things clear. The first was that he wished me to present the cases for both the prosecution and the defence, and report all the important available facts. Some of these facts are common knowledge, others have never been told before. Many of the latter concern his activities in the years before the bombing. While he swears that he is entirely innocent, he accepts that his account of those days may appear suspicious to some, especially those unfamiliar with the Libyan way of life at the time. On the advice of his lawyers, he opted not to give evidence at his trial, in part because it was clear that, in the hands of a skilful cross-examiner, some of the details could be made to appear damning. We could easily have avoided those subjects in this book, but it is important that readers know all the available facts, not only those that are most favourable to him. He provides explanations for them all and leaves it to you judge those explanations.

Secondly, he does not accuse anyone else of the bombing; all he knows is that neither he, nor Libya, was involved. As the book explains, the international investigation by the police and Western intelligence services initially suggested that other individuals, groups and nations were responsible. This information is included in order to provide you with a full picture; however, the case against those others may be as flawed as the one against him.

The past few years have seen the Western powers wage a disastrous ‘War on Terror’ in the Middle East and on the basis of false evidence. As the drums of war continue to roll, he is concerned that, even so long after Lockerbie, the old evidence will be resurrected and used as a pretext for new battles against the West’s enemies. He therefore says, loud and clear, that he holds no other individual, group or nation responsible for the bombing, and Lockerbie should never become an excuse for further bloodshed.

Finally, we are both painfully aware that publication of this book will upset the many relatives of the Lockerbie dead who believe him to be guilty. They continue to have our utmost sympathy for their terrible loss.

Abdelbaset said to me many times, ‘I understand that the public will judge me with their hearts, but I ask them to please also judge me with their heads.’ To make that judgement, you need the facts. This book presents many that were previously hidden. Please consider them all – you are now his jury.

I’m often asked, ‘What’s he like?’ I answer that he is a normal man who dealt with his appalling circumstances with remarkable patience and good grace. He is intelligent, a little shy, often humorous and quietly generous. His family and his Muslim faith are the twin pillars of his life and mean everything to him. For me, as for the prison officers, one characteristic stands out above all others – he is innocent.

Acknowledgements

Although this book bears my name, it draws heavily on the work of Abdelbaset’s legal team, with whom I had the pleasure of working for three years: solicitors Tony Kelly, John Scott, Laura Morton and Jennifer Blair; advocates Maggie Scott QC, Jamie Gilchrist QC, Martin Richardson and Shelagh McCall; investigator George Thomson and research assistants Paul Scullion and Aileen Wright. Our expert witnesses, Dr Jess Cawley, Dr Roger King and Dr Chris McArdle, helped me get to grips with the forensic evidence by patiently answering my non-expert questions in plain English. Numerous other witnesses have been kind enough to speak to me, including many who searched the Lockerbie crash site. I’m also grateful to Gunther Latsch of Der Spiegel for helping me to unravel events in Germany.

My agent David Godwin took on the book in the knowledge that it would yield more headaches than revenue. Hugh Andrew at Birlinn recognised the story’s importance and bravely opted to put principle before profit. His colleague Tom Johnstone then brought the book smoothly and skilfully to fruition, with the help of Andrew Simmons, Jan Rutherford and Jim Hutcheson. Susan Milligan provided sharp-eyed proofreading and Roger Smith produced a very thorough index.

My friends in Glasgow fed me, lent me their spare rooms and were wonderful company during my times in the city. My family has been constantly supportive of my unusual mission, especially Anja, without whose care and soothing words I would certainly now be grey.

My heartfelt thanks to you all.

Greatest thanks are due to my friend Abdelbaset for choosing me to tell his story. It’s been an honour. Time will prove you innocent.

Alan Topp was the first person on the ground to know something was wrong. An air traffic controller based at Prestwick Airport, he was monitoring Pan Am flight PA103 as it cruised over the Scottish border at 31,000 feet. The Boeing 747 Clipper Maid of the Seas was about to head west over the North Atlantic on its way from London Heathrow to New York JFK. Everything seemed normal. Then, suddenly, the radar image on his screen fragmented and the altitude data disappeared. PA103 was no more.1

It was 19.03 on Wednesday 21 December 1988. He didn’t yet know it, but Topp had witnessed Britain’s worst ever aviation disaster. Within minutes, the flight’s 259 passengers and crew were dead. Something had torn through the fuselage, opening the mighty aircraft like a tin can.

Until that night, the small Scottish border community of Lockerbie was unknown to most outsiders, but by morning it was known across the world. By a wretched twist of fate, much of the aircraft had fallen on the town. At Sherwood Crescent, close to the main A74 road, the fuel-laden wings had exploded, leaving a crater where houses once stood. Eleven residents were killed, bringing the deathtoll to 270. A few hundred yards away, the Rosebank estate was hit by a large section of fuselage. Incredibly, no one was killed, but the locals faced the twin horrors of destroyed homes and a neighbourhood that had become a charnel ground. Three miles to the east the aircraft’s decapitated cockpit came to rest in a field, providing the tragedy with its defining image.

Twenty-one nationalities were among the dead. The great majority were Americans returning home for Christmas, including US Army personnel stationed in West Germany and 35 Syracuse University students who had been studying abroad.

Many of the victims’ families learned of the disaster through the newsflashes that punctuated the Christmas TV schedules. As the terrible realisation dawned that their loved ones were on the flight, some congregated at Heathrow and JFK, desperately seeking news. Eventually it became clear there were no survivors, and they were left to cope with the searing pain of sudden bereavement.

The trauma was not confined to the relatives. Everyone who attended the scene was affected. For the police, military and civilians tasked with combing the scene for bodies it was especially distressing. One of the officers later recalled: ‘They were in all sorts of states: some were intact, others weren’t, a lot of them had their clothes completely ripped off them. I remember every single one of them, every single one. I mean most of us were family men and you’re looking at all these kids – what on earth do you say to your kid when the plane’s falling apart?’2

As dawn broke on 22 December, Lockerbie’s full horror was revealed. Not since the Second World War had the UK witnessed such devastation. For miles east of the town the landscape was peppered with debris. The bodies were removed within a few days, but for weeks searchers came across shattering reminders of the human catastrophe.

Scattered among these Christmas presents, photographs and personal mementos lay clues to the disaster’s cause. Within a week there were sufficient to sustain a shocking conclusion: PA103 had been downed, not by an accident or an act of God, but by callous and calculating humans intent on murder. It sparked the biggest criminal inquiry in UK history. By its end just one man had been convicted. The wrong man.

Plane crashes hold a particular terror for anyone who has worked in the airline industry; we all secretly fear that it will one day happen to us. Whenever I learned of one I felt a shudder of dread and my stomach knotted. Lockerbie was no different. I remember seeing the unearthly scenes from the crashsite and the raw grief of the newly bereaved. Their torment seemed unimaginable and, as with all decent people, my heart went out to them. As an airline man I also had great sympathy for the staff of Pan Am, who I knew would be deeply affected.

It was not until at least a day later that I learned of the disaster. As the horror was unfolding on the Scottish hillsides, I was at a family gathering to mark the birth of my niece a week earlier. It was the only landmark in an otherwise ordinary day. That morning I had flown back to Tripoli after an overnight stay in Malta and, as far as I recall, I then went to my office and spent the afternoon meeting the partners in my latest business venture.

Like most people, once the immediate shock of the disaster had faded, I didn’t follow the story closely in the media. It was not until spring 1991 that I received the first inkling that my fate would be inextricably coupled to the bombing. Out of the blue, a Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA) colleague in Zurich called me at work. He said he was checking that I was there and would call back, which I thought odd. A few minutes later he rang back from a pay phone. He said the FBI and the Scottish and Swiss police had just paid him a visit and were asking questions about me. I asked why. He said they seemed to be investigating the Lockerbie attack and were interested in my background and my activities. He told them all he knew: that I was a normal, decent man who, when in Zurich, would buy presents for his wife and children. He advised me against travelling to Switzerland, but I said that, if the police wanted me, then I would go.

I called my relative Abdulla Senoussi, who had a senior position in the Libyan intelligence service, the JSO, to see if he knew what was going on. He didn’t and he advised me not to travel until we had a clearer picture. I repeated that I was happy to speak to the Swiss police. He could have issued an order preventing me travelling, but he merely repeated his advice and promised to let me know if he learned anything more.

Not long afterwards I received a call from a Maltese man called Vincent Vassallo, who ran a travel agency in Malta with my former LAA colleague, Lamin Fhimah. He said he was trying to get hold of Lamin as the Scottish police and FBI had been to the office and were asking questions about us. They were especially interested in Lamin’s desk diary for 1988. I called Lamin, who was as puzzled as I was. He was happy for Vassallo to hand over the diary and was prepared to go to Malta to answer questions, but he too was advised against it. I didn’t give the matter too much thought over the coming months. We were curious to know why the police were interested in us, but assumed they considered us as potential witnesses.

Nothing, then, could prepare us for the shock to come. On Thursday 14 November 1991, American and Scottish prosecutors simultaneously announced that they were charging us with the Lockerbie murders. I heard the news on the BBC’s Arabic radio service. At first I assumed it was referring to some unknown namesakes, but, as the details were described, I realised with horror that we were the wanted men. In an instant I was plunged into a nightmare from which there seemed no escape. Amid the mental firestorm, all I could think was, ‘Why us?’ We were loving family men, who respected all human beings regardless of their nationality, religion or colour.

As I began to compose myself, it struck me that we had become pawns in the long-running power game waged against Libya by the US government. My next thought was that I did not want my family to hear the news, especially my wife Aisha, as she was five months pregnant with our third child. They had always believed me to be gentle and honest, but what if they thought I was guilty? The shame would be too much to bear.

On Thursdays, I used to go home early for my lunch and then in the afternoon drive around Tripoli with Aisha and our two small children.iAisha would usually listen to a BBC music programme, but I was anxious because it was always followed by a news bulletin, so I persuaded her to listen to a Libyan station instead. She didn’t comment, but I’m sure she noticed that I was behaving oddly.

On Fridays we always went to lunch either to my parents or hers. When Aisha said she wanted to go to hers, I pretended to be unwell and she agreed that I should stay at home.

The next day the story was being reported across the world. The time had come to break the news; if Aisha didn’t hear it from me, she was bound to find out from others very soon. Naturally she was horrified, although she’d guessed by her family’s rather strange behaviour at lunch that something was wrong. I swore to her that I was entirely innocent, but she knew very well that I was incapable of harming anyone. The news soon spread to my whole family. Everyone was shocked and upset, especially my mother. Thankfully, no one for a minute believed I was guilty – ‘Anyone but Abdelbaset’ was the universal refrain.

Lamin had been in Tunisia when the indictments were announced, and had not returned until the following day. His face was on every news bulletin and newspaper in the world, yet no move was made to arrest him. This was perhaps the first indication that some of our enemies had no desire for the accusations to be tested in court.

What, then, was the case against Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifa Fhimah? Under normal Scottish criminal procedure, it would not have been made public until the men reached court. But this was no ordinary case. The Scots and American prosecutors each set out the basis of the charges in detailed indictments, which were announced to the media at simultaneous press conferences in Edinburgh and Washington DC.

Both men were alleged to be undercover agents of the Libyan intelligence service the Jamahiriya Security Organisation (JSO). It was claimed that on the morning of 21 December 1988, the day of the Lockerbie bombing, they put an unaccompanied brown Samsonite suitcase containing an improvised explosive device (IED) on board Air Malta flight KM180 from Malta to Frankfurt. This so-called primary suitcase was tagged for New York on Pan Am flight PA103, causing it to be transferred at Frankfurt to Pan Am feeder flight PA103A to London Heathrow, and at Heathrow to Pan Am flight PA103.

The device incorporated an explosive, which Lamin was alleged to have stored at his office in Malta, where he had been the Station Manager for the state-owned Libyan Arab Airlines. It was built into a Toshiba RT-SF16 radio-cassette player, a large number of which had been bought by the General Electronics Company of Libya. More importantly, it was activated by an unusual timer, made by a Swiss company called Mebo, that was allegedly one of unique batch of 20 supplied exclusively to the JSO.

The two men were said to have packed the device into the suitcase along with clothes and an umbrella, which Abdelbaset had allegedly bought in Malta two weeks before the bombing, on 7 December 1988. They supposedly took the case to Malta on 20 December, with Abdelbaset travelling on a coded passport under the name of Ahmed Khalifa Abdusamad. The following morning he flew back to Libya on an LAA flight, which checked in shortly before KM180. It was alleged that, prior to departure, with the help of luggage tags illegally obtained from Air Malta, they were able to subvert the baggage system of Malta’s Luqa Airport to get the suitcase onto KM180. They were alleged to have used a number of JSO front companies in the course of the conspiracy, most importantly ABH, which shared Mebo’s premises in Zurich, and Medtours, the travel agency run by Lamin and his friend Vincent Vassallo in the Maltese town of Mosta.

Although no one else was charged, various other alleged JSO members were mentioned in the indictment. Among them were two good friends of Abdelbaset, Said Rashid (to whom he was also related) and Ezzadin Hinshiri, both of whom were fairly senior JSO officials, and who were said to have procured the timers from Mebo in 1985. Among the others were Badri Hassan, who was said to be ABH’s man in Zurich, and another of Abdelbaset’s acquaintances, Nassr Ashur. Shortly before the bombing, Hinshiri and Hassan had allegedly attempted to obtain 40 more of the timers from Mebo.

Taken at face value, the evidence against the two men appeared to be strong. Again, in a normal Scottish criminal case it would be closely guarded, but that was of no concern to the US government, who issued a summary of it in a ‘fact sheet’ accompanying their indictment. Even without the sheet, sufficient details of the evidence had been leaked out over the years to paint a fairly detailed picture of the prosecution case well before it was presented to the Court nine years later.

The first reported breakthrough was the discovery that a number of blast-damaged garments in the primary suitcase were made in Malta. Enquiries on the island linked the clothes to a small family-run shop in Sliema called Mary’s House. Miraculously, the shopkeeper, Tony Gauci, remembered selling the clothes to an oddly-behaved man shortly before Lockerbie. Later to become the star witness against Abdelbaset, he said the mystery customer was Libyan and had little regard for the clothes’ sizes.

The Malta link was confirmed by baggage records unearthed from Frankfurt Airport. These appeared to show that a suitcase from an Air Malta Flight, KM180, had been transferred to the Frankfurt to Heathrow feeder flight, Pan Am 103A. There was no record of anyone having transferred from KM180 to flights PA103A and PA103, and none of the victims were known to own a brown Samsonite suitcase like the primary case. The police inferred from all this that the suitcase contained clothes from Mary’s House, and was placed unaccompanied on KM180. They believed that it must have been labelled for automatic onward transfer at Frankfurt and had somehow evaded Pan Am’s security checks prior to being loaded onto PA103A.

The third key plank of the case was a fragment of electronic circuit board, which a British forensic expert found embedded within a piece of blast-damaged shirt, of a type sold at Mary’s House. In 1990 American investigators matched the fragment with a timer, known as an MST-13, which was eventually linked to the Swiss company Mebo. The company’s co-owner, Edwin Bollier, said that the timers were designed and made to order for the Libyan intelligence service and that only 20 were produced, which he personally delivered to Libyan officials. He also told the police that the firm shared its offices with ABH. This company had been established by Badri Hassan and Abdelbaset was one of five partners, all of whom were Libyan. Bollier said that he had attended tests in the Libyan Desert, near the town of Sabha, in which the timers were used to detonate explosives. Then, in December 1988, Hassan had asked him to produce 40 more devices. His account appeared to be borne out by the fact that, a few months prior to Lockerbie, one of the timers was reportedly seized, along with explosives, from two Libyans who were attempting to enter the West African state of Senegal.

Abdelbaset was the common link between Bollier and Malta. He had left Malta on the morning of the disaster and had visited the island two weeks earlier, at approximately the time that Gauci said he sold the clothes. It was speculated that, as former Head of Security for LAA, he knew how to best get a bomb onto an aircraft undetected and, as LAA’s Malta Station Chief, Lamin was ideally placed to help him.

In February 1991 the police appeared to have scored a bull’s eye when Gauci picked out a photograph of Abdelbaset as resembling the clothes buyer. Three months later, with Lamin’s consent, they obtained his Medtours diary. There were two suspicious entries for 15 December 1988. The first was preceded by an asterisk and read ‘Take taggs from Air Malta.’ The word ‘taggs’ [sic] was in English and the remainder in Arabic, and the letters ‘OK’ had been added at the end in a different coloured ink. The second entry, which was in Arabic, said ‘Abdelbaset arriving from Zurich’. A further note at the back of the diary read ‘Take/collect tags from the airport (Abdelbaset/Abdusalam)’. Again, the word ‘tags’ was written in English and the remainder in Arabic. The entries supposedly demonstrated that Lamin had obtained the Air Malta baggage tag required to smuggle the bomb onto KM180.

The case against the two men appeared to be sealed when a Maltese-based employee of Libyan Arab Airlines, Majid Giaka, told the FBI that, at around the time of the disaster, Abdelbaset had arrived in Malta with a brown hard-sided suitcase similar to the Samsonite one that contained the bomb, and that Lamin carried the case through Customs. He also said that Lamin had stored explosives in his office desk.

The media was briefed that Lockerbie was Libya’s revenge for the US’s 1986 air raids on Tripoli and Benghazi. There was no evidence to implicate any other country, the prosecutors made clear; this was ‘a Libyan job from start to finish’.3

Under the 1971 Montreal Convention, those accused of aviation terrorism are entitled to be tried in their own country, but, having issued the indictments, the US and UK governments tore up the rule book, demanding that Libya hand the two men over for trial in Scotland or the US.4 Incredibly, despite the charges being unproven, they also demanded that the country admit responsibility and pay compensation for the bombing. When the Libyan government refused to buckle, the two countries successfully sponsored two UN Security Council resolutions, 731 and 748, which echoed the demands.ii Libya again refused, and in 1992 the UN announced sanctions against the country.

In March 1992 the Libyan government launched legal actions against the United States and UK at the UN’s judicial body, the International Court of Justice, alleging a breach of the Convention. The application stated: ‘Whereas Libya has repeatedly indicated that it is fulfilling its obligations under the Convention, the United States has made it clear that it is not interested in proceeding within the framework established by the Convention, but is rather intent on compelling the surrender of the accused in violation of the provisions of the Convention. Moreover, by refusing to furnish the details of its investigation to the competent authorities in Libya or to cooperate with them, the United States has also failed to afford the proper measure of assistance to Libya required by Article 11 (1) of the Montreal Convention.’5

Lamin and I, of course, denied that we had been involved in any way in the bombing. It was clear, however, that the Libyan authorities were not prepared to accept our denials. We were ordered to attend JSO’s offices, where we were grilled for hours. Lamin faced tougher questioning than me because he had been based in Malta. They asked if we might have been duped into putting a bomb on an aircraft and we were adamant that we had not. Lamin had a relative in America who was known to be an opponent of the Libyan government, so I suspect that the JSO believed that we might have been put up to the bombing in order to cause trouble for Libya. Most of the questions were asked by a man called Abdusalam Zadma, who had a fearsome reputation in Libya. Lamin became very upset, which, to our great relief, eventually helped convince Zadma that we were innocent and should be released.

Nevertheless, a judge was appointed to investigate the case. He confiscated our passports, identity cards and driving licences and placed us under house arrest. We were ordered to report weekly to a police station and not to leave Tripoli without the Court’s permission. The investigation got nowhere, because it proved impossible to obtain further details of the evidence from the Scottish and American authorities, but, despite my objections, the restrictions remained.

We were advised to take legal advice, so a few days later met with two well-known Tripoli lawyers, Dr Ibrahim Legwell and Kamal Maghour. It was decided that Legwell would represent me and Maghour, Lamin. We saw them a few times over the next week or so. There were never any government people at the meetings, but on one occasion Maghour introduced us to a British lawyer, who explained English, rather than Scottish, criminal law.

No Arabic translation of the indictment was available, so we had only a limited understanding of the charges. The lawyers set out what they saw as the key allegations: that the JSO had procured bomb timers from Mebo; that on 7 December 1988 I had bought the clothing in Malta; that we had travelled together to Malta the day before the bombing; that I had travelled under a false name; and that we had taken with us a brown Samsonite suitcase.

I told the lawyers the truth: Lamin and I did fly to Malta on 20 December and I travelled under a different name, but neither of us took a suitcase; I was connected to Mebo, via the company ABH, in which I was a partner, but I knew nothing about timers; I was in Malta from 7 to 9 December, but I didn’t buy clothes there. Most importantly, we both made clear that we had nothing whatsoever to do with Lockerbie.

Twelve days after the indictments were issued, Legwell called to tell me that the government had requested that we do a TV interview with the American channel ABC. He explained that the American media had reported that we had been executed, and it was feared that the US government would believe Libya was trying to evade justice and might therefore attack the country, as it had in 1986. He said that the purpose of the interview was simply to demonstrate that we were still alive, but, to my horror, added that the TV crew would be arriving at my house at lunchtime. He reassured me that the interviewer, Pierre Salinger, knew our Foreign Minister, Ibrahim Bishari, and that the questions would focus on the impact of the indictments upon us and our families. He said that Lamin and I would be interviewed separately, and further reassured me that one of our legal representatives would be present, along with an interpreter. Just in case the interview strayed outside the agreed areas, he advised me strongly against discussing any of the specific allegations.

At 13.00 two government cars pulled up outside our house, each with an official driver. Salinger got out, along with a cameraman, a soundman and a producer. Accompanying them were Bishari’s secretary and another Arab man, whose role was unclear to me, but there was no sign of a lawyer or interpreter. While the crew set up their equipment, Aisha and I organised refreshments. Bishari’s secretary told me that Salinger was a good friend of the Minister and promised me that the interview would be very easy and would cover only family matters.

We made small talk while waiting for the lawyer and interpreter to arrive. Salinger asked if I was really a flight dispatcher for Libyan Arab Airlines. I told him I was and that I had a licence from the United States, which surprised him.

After half an hour neither the lawyer nor the interpreter had appeared. I asked Salinger if we could delay the interview, but he said he was working on a tight deadline and had another assignment to fulfil while in Libya. He reassured me that the interview wouldn’t be challenging and said my English was good enough to cope without an interpreter. I agreed that the interview could go ahead, but remained concerned by the lawyer’s absence.

Unfortunately Salinger failed to keep his promise and repeatedly asked me about the indictment. Had a lawyer been present, he could have intervened to stop the questions, but, with no one to guide me through the minefield, the interview was a disaster. I knew I should avoid discussing the allegations, but refusing to answer these direct questions would inevitably fuel suspicions that I had something to hide. However, if I told the truth, it was inevitable that the US government would reject my claims of innocence and seize upon the admissions that tallied with the allegations. Caught in the headlights, I did what I thought best, which was to lie.

His questions about my movements on 20 and 21 December 1988 were especially awkward, as I had not only used my Abdusamad coded passport, but had done so behind Aisha’s back. Although she by then knew about the coded passport, she wasn’t aware of all my travels and would have been upset by the deception. I flatly denied making the trip, claiming that I was at home in Tripoli, and said I’d never heard of Abdusamad. I also denied any connection to Mebo, although I told him truthfully that I knew nothing about timers. I admitted that I was in Malta from 7 to 9 December and asked Aisha to bring my passport so I could show him the entry and exit stamps. I couldn’t recall why I’d been there, but was certain that I’d never bought clothes. On the most important issue I also told the truth – I was innocent. I added that if British and American investigators wished to come to Libya I was prepared to answer their questions. Salinger subsequently became convinced I was innocent, but, by lying to him, I’d badly undermined my chances of proving that innocence in court. If I were ever to take the witness stand, the prosecution would make hay branding me a liar.

In 1992 our lawyer Dr Legwell instructed Scottish lawyer Alastair Duff, of the Edinburgh firm McCourts. Shortly afterwards he was invited to Tripoli and we met him at Legwell’s office. I asked him directly: ‘If we went to Scotland to appear before the court there, would we receive a fair trial?’ His answer was immediate and unequivocal: ‘No.’ In his view it would be impossible to find a jury which would not have been swayed by the media coverage of the case since the indictments, almost all of which assumed we were guilty. I greatly respected him for his honesty, as he could easily have given an answer that was good for his career and bank balance.

When, years later, we agreed to be tried by judges rather than a jury, Duff again warned us that we were unlikely to receive a fair trial. If only I had heeded his words.

I was born on 1 April 1952 in Tripoli, the third of eight siblings. It was my father who chose my name. He worked for the Libyan Customs service and my mother looked after the home and supplemented the family income by sewing for neighbours. Libya at the time was a poor country, and for most people everyday life was a struggle. Until I was nine we shared our house with two other families. We then moved to our own house, which my father had built.

As a young child I was sick for several months with a chest infection and for two months had to endure twice daily injections. My school was supervised by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation, UNESCO, which ensured that we received daily vitamin supplements.

After primary school I attended intermediate school for three years, followed by three years at secondary school. By the standards of the time, I had a fairly normal childhood and teenage years, and had the usual range of interests. My passion was football and, when we could afford it, I liked the cinema.

Like most people in Libya, I was brought up a faithful Muslim. Islam was, and remains, the binding force of our society; but, although we’re a devout country, we have never been an extremist one. Sadly, that is a distinction that has been obscured by the hysterical rhetoric of the War on Terror. To me, and every Libyan I know, Islam is a religion of peace and charity, which can never be twisted to justify violence.

Shortly after finishing school in 1970, I read an advertisement by the Libyan Commercial Marine Organisation, which was recruiting students to study marine engineering in the UK. I applied and was one of 55 candidates accepted onto the five-year course at Rumney Technical College in Cardiff.

In truth marine engineering held no great appeal for me, as I really wanted to be a ship’s captain or navigator. Unfortunately, I subsequently discovered that my eyesight was not good enough. My hopes dashed, I decided to abandon my course and return home.

Back in Libya I was torn between getting a job or going to university. My father had retired, leaving the family short of money, so I opted to find work. I answered an advert for the job of flight dispatcher with Libyan Arab Airlines. I was one of 12 of the 30 applicants who were accepted. A flight dispatcher is responsible for preparing a so-called flight plan for each flight, which contains details of the route, meteorological information, the time of entry to each country, the flight level, the arrival time and an alternative airport in case there are problems. The plan is given to the pilot and representative of the aviation authority at the airport of departure, each of whom have to sign and keep a copy.

Most of our training took place in Libya, but at one point we were sent to Pakistan to obtain a Flight Operations Officers Licence. This didn’t go well, so we returned home and were subsequently sent to complete the training in the United States. I returned to the country twice for refresher courses in 1977 and 1981.

After four years in the job, I had risen through the ranks to become the airline’s Chief Flight Dispatcher and then Controller of Operations at Tripoli Airport. I was next appointed Head of Training, but by then I had grown restless. I wanted to improve my education, so in 1975 I entered the University of Benghazi as an external student to study geography. I came top of my class every year, and on graduating in 1979 accepted an invitation to join the staff as a teaching assistant in climatology, on the promise that I would be sent to the United States to do a Master’s Degree or a PhD in climatology. The Chairman of LAA at the time, Badri Hassan, wanted me to stay with the airline and said it could sponsor my studies in America, but the University was having none of it, so I had to resign from LAA.

Despite my obtaining an offer from the University of Pennsylvania, my own university’s promise never materialised, as various academics had persuaded the government that there was no need to send students abroad to study. It was a ridiculous notion, especially in relation to my chosen field, which was reliant upon comprehensive meteorological records of the kind that were simply not available in Libya. There was no point holding on to a dead-end academic job, which paid less than half of what I was earning when I left LAA. Disillusioned, I resigned at the end of 1979 and returned to work for the airline. I was immediately sent to Toulouse in France to attend a course organised by the Airbus company, as LAA had recently signed contracts to purchase a number of Airbus aircraft.

As I approached my 30th birthday, I knew it was time to think about marriage and settling down into family life. My parents and older sisters suggested that I should consider a girl called Aisha, one of ten siblings from a neighbouring family who had lived in our area of Bab Akarah for a long time. I was attracted by the fact that her parents were modest, yet highly respected among local people. Her father Al Haj Ali was a medical assistant in a local hospital and her mother Salma was the head of a primary school.

My eldest sister Zeinab took the lead, and along with other family members visited Aisha’s family to discuss the matter. The discussions went well, and after a few weeks the engagement was completed. At this point I had still not set eyes on my bride-to-be. Western readers might find this strange, but the arrangement was in accordance with Libyan community and family traditions. In contrast to Western convention, an engagement marks the beginning rather than the end of the courtship process, and allows a couple to get to know each other and establish whether they are compatible.

I met Aisha for the first time shortly after the engagement was agreed. We chatted and got on well. I visited her a few more times, and eventually it was decided that we should go ahead and get married. We tied the knot on 18 March 1982, around nine months after our first meeting.

Our first home was a flat on the fourth floor of an apartment block in the Bab Bengashir area of Tripoli. In 1983 we were blessed with the birth of our first child, a baby girl, who, at my mother’s suggestion, we called Ghada. She was followed three years later by our first son, Khaled, whose name I chose. We were very happy, but the flat wasn’t suitable for raising a family, as it was fairly small and the lift was usually out of order. I could see the physical and psychological toll that it was taking on Aisha and I feared for the children’s health. We decided that the best and most affordable solution was to build our own house. I bought a plot of land in Ben Ashour from the Tripoli municipal authority and took out a bank loan to pay for the construction, but progress was to be painfully slow.

By the time I returned to LAA after working at the University of Benghazi, Badri Hassan had been ousted as Chairman of LAA as he had been caught receiving illegal commission payments. He was subsequently convicted, and for a few years was forbidden to leave Libya. His replacement, Captain Ali Hannushi, created a lot of petty problems for me. The Minister of Transport didn’t like him and wanted to get rid of him, so decreed that the airline should be run by a committee, rather than a chairman. Six or seven people were selected to serve on the committee, four of whom were from within LAA and the others from outside, including a military man who was appointed as Chair. When I was subsequently promoted by LAA to the position of Tripoli Station Manager, I became one of the four LAA representatives.

It was during this period that I first got to know Lamin Fhimah. He had joined LAA in 1975, three years after me, and, like me, was originally trained as a flight dispatcher and based at Tripoli Airport. He was later selected to work in operations control at LAA’s head office and was appointed Malta Station Manager in 1982. In 1984, Aisha and I stopped over on the island for a few hours on our way back to Tripoli. On learning of our arrival, Lamin invited us to lunch with his family. Until that day I had never got to know him socially. His family were very welcoming and kind. When his wife learned that we had had a daughter a few months earlier, she gave Aisha as a gift a small bag for carrying baby items.

After that I would make a point of seeing Lamin whenever I travelled through Malta. We would often go shopping together, as he knew the best places to buy essentials and gifts that I wanted for my family. We were never close friends and didn’t socialise much together, but he was a nice man and good at his job. After the indictments were issued against us, one newspaper quoted an anonymous source who claimed he was a religious fanatic committed to destroying America.1 This was a total fabrication. Lamin loved life in Malta and the Western-style freedoms on offer there, including the chance to drink. He was popular and considerate, in short the last person who would commit mass murder in the name of Islam, or any other cause.

In 1985, after I had served on LAA’s committee for around two-and-a-half years, the Minister decided to reinstate Captain Hannushi and disband the committee. Although I continued to receive a salary I was, effectively, out of a job.

At that time LAA’s security was provided by the JSO. It was JSO personnel who searched passengers and travelled on flights to prevent hijackings, which were quite common at that time. Relations between the regular airline staff and the security people were often strained, especially over the issue of firearms on aircraft. The JSO routinely carried their guns on flights and made it quite clear that they would use them against hijackers. The crews were very concerned, as a misplaced bullet could easily endanger the whole plane. In order to resolve such conflicts it was decided that the security officers should become full-time LAA employees. It was expected that the change-over would take around a year to enact. To accelerate the process, Abdullah Senoussi, who was then a departmental head in the JSO, and my friend Said Rashid, who was one of his deputies, asked if I would help to train the JSO staff who were to be transferred in all the relevant aspects of the airline’s operations. I agreed, and soon after was appointed LAA’s Head of Airline Security for the transition period. I remained in the position from the start of 1986 until the end of November that year. Officially I was on secondment to the JSO, but my salary continued to be paid by LAA.

In addition to the training, my primary responsibility was to ensure the safety of all flights and passengers. Ironically, given the false accusations that were later made against me, I had to keep abreast of warnings about potential terrorist threats, which I received from the JSO and the International Air Transport Association (IATA). I remember in particular receiving warnings about the Lebanese Shia faction Amal, which at one point was alleged to be threatening Libya.iii

At a more mundane level, I was also required to resolve any residual conflicts between security staff and flight crews. The crews liked to deal with me because they viewed me as one of their own, but the ex-JSO people were mistrustful, considering me to be an airline man with little understanding of intelligence and security matters.

During my tenure as Head of Security, it was decided that every LAA Assistant Station Manager would be chosen from among the former JSO employees. All were required to submit security reports to me. Among them was Lamin’s Deputy, Majid Giaka, whose name would return to haunt me. It was agreed with the JSO that LAA would continue to pay the Assistant Station Managers’ salaries and would recover the money from the JSO. I was different, however, as officially I was an LAA staff member who was on secondment to the JSO. I continued to receive my salary from LAA and was never paid by the JSO. It was the only time I ever worked for the JSO, yet the US and Scottish prosecutors branded me a senior intelligence agent, a claim slavishly parroted by the world’s media ever since.

My interim post finished at the end of 1986. In January 1987 I was again co-opted by Abdullah Senoussi, this time to become the coordinator of the Centre for Strategic Studies in Tripoli. The Centre, which was the brainchild of the former Foreign Minister and JSO chief, Ibrahim Bishari, was intended to ensure that the government was better informed about world events. It was one of six centres in Libya operating on similar lines, the others being for African studies, Libyan history, oil studies, industrial research and marine biology.

There was no money in the Foreign Ministry budget to establish the Centre, so funding was found from the JSO’s. Senoussi oversaw its creation and maintained a close interest in its work; however, it was not, as some have portrayed it, a sinister wing of the JSO. Its annual budget was only the equivalent of around £30,000, some of which came from other government departments. It was never headed by a military or JSO officer – indeed, only three employees belonged to the JSO: an administrative and financial supervisor, a typist and a driver.

More importantly, its work was straightforwardly academic; its research was based almost entirely on publicly available sources and its reports were distributed to all its sponsoring departments. With one exception, the research studies were wholly unrelated to security or intelligence matters. Subject areas ranged from water resources in Africa, to strategies for developing the desert region, and the economy of the Soviet Union. The exception was a study of Islamic fundamentalism among young people in Libya. There had been an upsurge of the phenomenon resulting in some violent disturbances, which had generated serious security concerns. The Centre was called upon to help the JSO, and the government as a whole, to understand the problem. I met with some of the professors to discuss how they might best research the issue. It was agreed that we should gather as much international literature as possible on the subject. They also wanted to interview fundamentalists who had been jailed following the disturbances, but permission was refused, probably because the JSO didn’t trust the Centre to do its spying.

The Centre was not at all secretive. Academics would come and go freely, and on one occasion a French TV company, Channel 5, filmed the outside of the building for a feature on the Paris to Dakar car rally, the Libyan stage of which I was involved in organising. This would never have been allowed at a JSO facility. I often met friends there and held business meetings unconnected with my job as coordinator, as it had fairly advanced facilities by Libyan standards, such as telex machines and reliable phone lines. I enjoyed working with the professors and found the academic atmosphere very stimulating. I was able to put to use the organisational skills that I’d learned at LAA. My proudest achievement was organising the construction of an extra storey for the building, which meant the professors no longer had to share rooms.

Given the Centre’s very limited budget, it was decided that my salary should continue to be paid by LAA, so officially I was only ever on secondment from the airline. I knew there was a good chance that I would one day return to LAA and therefore took care to maintain my flight dispatcher’s licence. This required me every six months to undertake a so-called route check, which involved flying with LAA as a dispatcher.

In truth, my job at the Centre was rarely taxing and was effectively only part-time. It meant I had plenty of time for other, more lucrative ventures. In 1986 my former LAA boss Badri Hassan told me that he had established a Liechtenstein-registered business in Zurich called ABH, which was acting as a mediator in the sale of an ex-LAA aircraft to a Swiss company. He chose the name ABH after the initials of his son Ali Badri Hassan, although the company letterhead said Aviation Business Holding Company. He explained that there was considerable commercial potential in supplying equipment and replacement parts to LAA and other state enterprises. Libya was subject to strict US sanctions, which banned the sale of many industrial and technical goods. Since many of its aircraft were made by the American company Boeing, the impact on the airline was especially severe. The only way in which LAA and government departments could source such equipment was via third parties, which were often small companies. As these firms were uneasy about dealing directly with Libyan state bodies, the government slightly eased its tight restrictions on private enterprise, enabling Libyan entrepreneurs to make deals on behalf of LAA and other organisations affected by the sanctions. Hassan asked me if I’d like to become a partner in ABH. I agreed, and thus began my career as a sanctions-buster.

While the work might have been out of the ordinary, there was nothing unusual in me combining my work for the Centre with business activities. Many state employees became small-time entrepreneurs in order to supplement their meagre wages. The government generally tolerated this moonlighting, especially after the tightening of sanctions in 1986.

Soon after taking up Hassan’s offer we were joined by one of my friends, Mohamed Dazza. Hassan suggested bringing in two other people: Nun Seraj, his former LAA secretary, and Abdelmajid Arebi, who was commercial manager of African Airlines, for which Hassan was an advisor. Hassan told me that he had earned $70,000 from the aircraft deal and that this would serve as working capital for the company. I opened an account at the Zurich Airport branch of the Credit Suisse bank, for which I needed only my passport and $100. I didn’t have to invest any more of my own money, as Hassan was instead relying on my experience in the aviation world and my good relationships with a number of state organisations, in particular LAA and the Civil Aviation Department.

There can be no doubt that my connection to such organisations was one of the reasons that I became a target of the police investigation. I could easily have lied and denied any close connection to state bodies and to the JSO officials named in the indictment, such as Abdullah Senoussi, Said Rashidivand Ezzadin Hinshiri, but it’s important that readers know the truth. They are all known to many other entirely innocent people. Libya’s professional class is small and its members often have a number of diverse jobs over the course of their careers, so intermingle professionally and socially more than they might in a larger country.

Unfortunately, my contacts within government departments were not sufficient to guarantee ABH’s success. The $70,000 injection proved to be insufficient seed funding. We realised that, if the company was to develop as we hoped, we required a commercial loan. We knew this would be very difficult if ABH was perceived to be Hassan’s company, as his corruption conviction was common knowledge in Libya. I offered to approach a personal acquaintance who was the head of one of the country’s commercial banks. As the application was to be in my name, it was decided to assign 90 per