Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

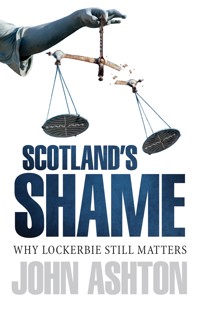

The bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over the small Scottish town of Lockerbie in December 1988 was one of the most notorious acts of terrorism in recent history. Its political and foreign policy repercussions have been enormous, and twenty-five years after the atrocity in which 270 lost their lives, debate still rages over the conviction of Abdelbaset al-Megrahi, as well as his controversial release on compassionate grounds by Scotland's SNP government in 2009. John Ashton argues that the guilty verdict, delivered by some of Scotland's most senior judges, was perverse and irrational, and details how prosecutors withheld numerous items of evidence that were favourable to Megrahi. It accuses successive Scottish governments of turning their back on the scandal and pretending that the country's treasured independent criminal justice system remains untainted. With numerous observers believing the Crown Office is out of control and the judiciary stuck in the last century, politicians must address these problems or their aspirations for Scotland to become a modern European social democracy are bound to fail.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 279

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SCOTLAND’S SHAME

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © John Ashton, 2013

The moral right of John Ashton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher

ISBN: 978-1-78027-167-5

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-642-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Jim Swire

Preface

1 Flawed Charges

2 Getting Away with Murder

3 A Nation Condemned

4 A Shameful Verdict

5 Burying the Evidence

6 A Bigger Picture

7 The Crown out of Control

8 A Failure of Politics

Conclusion: A System in Denial

Appendix 1: The Official Response to NewForensic Evidence

Appendix 2: Author’s Response to Crown Office Statement

Notes on the Text

Index

Acknowledgements

Having spent two and a half years writing Megrahi: You Are My Jury, I never imagined that I would write another book about Lockerbie. The fact that I have is down to Hugh Andrew and his colleagues at Birlinn, who understand the importance of the story and its particular importance to Scotland. My sincere thanks to them, especially Tom Johnstone for his editorial guidance and Jan Rutherford for coordinating the book’s publicity. I’m also grateful to Professor Bob Black, Robert Forrester, Tony Kelly, Morag Kerr, Simon McKay, Iain McKie and Robert Parry for their editorial advice and moral support. Dr Jim Swire has done more than anyone to keep the Lockerbie issue alive and I’m very honoured that he has written the book’s foreword. My wife Anja uttered not a whisper of protest when I told her that I wanted to write a new book, and she and our son Paolo have cheered me on throughout.

Foreword by Jim Swire

‘Love one another with a pure heart fervently, see that ye love one another.’

Peter 1:22 and Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-1876)

When I was a boy, some 70 years ago, I remember being sent away from my much loved home in the Isle of Skye, where our daughter Flora’s ashes now lie buried, to go to boarding school in Oxford. I dreaded those journeys; but when I was singing in the school choir there as a boy treble, a favourite hymn was Samuel Wesley’s anthem which, to glorious music, contains the command, ‘Love one another with a pure heart fervently, see that ye love one another.’

Through my long life it has often proved hard to follow that command to love one another, and I have often been a miserable failure at it, even in loving my own family as they deserved at times. But the greatest tests have come since our deeply loved elder daughter Flora was slaughtered, a day short of her twenty-fourth birthday, along with 269 others, in the Lockerbie atrocity of 1988. She was a beautiful, ebullient young medical student, so bright that she had volunteered temporarily to suspend her medical studies in Nottingham to do a research project at the country’s premier neurological institute in Queen’s Square, London. There she met a young American doctor who became her boyfriend. It was to him in Boston that she wanted to fly for Christmas 1988 after having asked her mum if it was OK for her to be away from the family for Christmas. How hard it is: if we had only said no . . . we would still have our Flora with us, and I would not be writing this now.

During the painful task of clearing out her London room after her death, we found on her desk a letter from Cambridge, my old university, accepting her to continue her studies there. We knew this meant we would have heard her excited voice, probably on Christmas Day, telling of her safe arrival and her acceptance by Cambridge. But it was never to be.

Now that John Ashton and so many others have been able to make it plain that the ‘official version’ of the Libyan Abdelbaset al-Megrahi’s guilt cannot be true, it has become increasingly difficult not to despise those who still try to defend the indefensible. Most of them do this out of ignorance, but some because they are told to do so, some to enhance their careers, some to conceal their own shame, some to seek greater power, some to make money, others because they genuinely see it as their duty to toe the official line.

When John Ashton’s second Lockerbie book, Megrahi: You Are My Jury was published in Edinburgh, an announcement from 10 Downing Street, which had not had time to study its contents, early that same morning condemned the book as an insult to the relatives. Now that fifteen months have gone by, there can be no excuse for the government’s failing to have studied afresh the origins of the murder of so great a number of innocent citizens, so clearly set out by Ashton. The failure to protect our families and the denial of the truth are the real insults for the relatives.

This, Ashton’s third Lockerbie book, shows that terrible mistakes have been made, and there are hints of something more sinister than simple human error. For us, being denied the truth has become the norm, but Ashton’s work is fresh and closely reasoned from his vantage point in possession of almost all the evidence available to both prosecution and defence. It seems that our own and certain other governments are deliberately concealing the truth from us. This is both wrong and futile, for Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights enshrines our absolute right to know the truth about the deaths and the failure to protect our families. The longer that government refuses to reveal all it really knows of the truth, the more certain it is that the Supreme Court or the European Court of Human Rights will have to intervene. There will be no mercy at the bar of history.

It has never been the aim of the Lockerbie victims’ relatives’ group, UK Families-Flight 103, to attack those who made mistakes; rather we seek ways to ensure that our courts shall function transparently and fairly in future. How much better that that the investigation and correction of what has gone wrong should come from within our own borders.

In 1990 the UK relatives were summoned to the US embassy in London to hear the findings of President George Bush senior’s Commission on Aviation Security and Terrorism. It seemed to be a review of how the US would fight terrorism in future – a foretaste perhaps of how the American ‘war on terror’ would later impact on all our lives. It sought to reassure us that there had been no sinister explanation as to why the Lockerbie aircraft had only been two-thirds full in the week before Christmas and how it came to be that some of our families had been told there were no seats to the US that week, only to be offered seats in the last few days before the flight, on the Lockerbie aircraft Pan Am 103.

However, one of our number, Martin Cadman, who had lost a son, was taken aside in the embassy by a member of the Commission and told quietly, ‘Your government and ours know exactly what happened, but they are never going to tell.’

Even the least imaginative among us might from then on have wondered, was this atrocity some incident in a great game of international politics, in which individuals and truth may be sacrificed for the perceived national interests of a whole country?

After all, five months before Lockerbie, a US missile cruiser, the USS Vincennes, had shot down an Iranian airbus killing 290 innocent people, and then the United States had awarded a medal to her captain and meritorious service ribbons to her crew. The Iranians had naturally bayed for revenge, an eye for an eye; was Lockerbie that revenge? If so was it in any sense ‘facilitated’ to avoid inevitable confrontation with Iran? What a terrible possibility; but fear of such a horror becoming public could explain the effort still ongoing by governments to obstruct the truth. We do know it was initially a given in intelligence and civil aviation circles that Lockerbie was indeed Iran’s revenge, so why was no coherent move apparently made to prevent it?

In 1991 Scotland and America decided to issue indictments against Megrahi and his fellow Libyan, Lamin Fhimah, claiming they had been agents working in Malta to get a Libyan-provided IED (bomb) aboard the Lockerbie flight by a circuitous route involving Frankfurt airport. Within days of the indictments against the two Libyans, American and UK hostages started to be returned to freedom by the Iranian-backed groups such as Hezbollah who had been holding them. One of the first two to be released was Britain’s Terry Waite.

The hostage issue was an enduring obsession for the Reagan and Bush administrations and had given rise to the disastrous and illegal Iran-Contra operation a few years earlier. It was perhaps not surprising that some of us began to wonder just what the driving forces behind the evolution of the Lockerbie investigation might be.

Then in 1998, following a meeting of Robin Cook, UK Foreign Secretary, with us, the UK relatives, in Edinburgh, and strengthened by the support of Nelson Mandela and American money under President Clinton, an arrangement was signed between the UK and Dutch Governments to allow a trial of the two accused Libyans in a ‘Scottish enclave’ within Holland.

Ever since the issue of the indictments in 1991, I had repeatedly visited Colonel Gadafy in Tripoli, slowly losing my fear of him and begging him to allow his two citizens to attend for trial under Scots law, which at that time I believed would offer a fair trial. During this time I also came to meet, liaise with and respect Professor Robert Black QC. A native of Lockerbie himself, and emeritus professor of Scots law at Edinburgh University, it was he who had defined the concept of a Scottish court sitting in a neutral country to try the two accused. His concept was modified before the court could sit in such a way that there was to be no jury, and the panel of judges was to be Scottish, not international.

Nelson Mandela had warned in Edinburgh that ‘No one country should be complainant, prosecutor and judge.’ But Scotland now became all three.

Along with one other member of the group, Reverend John Mosey, who had also lost a daughter, Helga, on the plane, and who has become a very dear friend, we attended throughout the Zeist trial of the two Libyans and their first appeal. It was a surreal experience. First we witnessed the grooming of US relatives by members of the prosecution team most evenings, and then much of the evidence seemed to be coherent but to point to a Syrian-based terror group, the PFLP-GC, which was closely associated with Iran, and not towards Malta and Megrahi.

Upon hearing the Zeist verdict, at first we felt very isolated in our realisation that the trial did not seem to have delivered justice; but then Professor Black, despite being the main originator of the concept of a neutral country trial and a leading upholder of Scottish justice, was amongst the first to publish warnings that the trial had not been a valid one under Scots law. In that he was joined by Professor Hans Köchler of Vienna, UN special observer at the trial, who found that the proceedings were not recognisable as justice. A host of others began to cry foul.

Apart from the unstinting love and support of my wife Jane, key among the new friends made during the first years of torture were the other members of our group, UK Families-Flight 103. Skillfully run by Jean Berkley and her husband Barrie, who had lost their son Alistair, the group has supported its members and sought truth and justice resolutely throughout all this time, often guided by solicitor Gareth Peirce, and despite the repeated insults we suffered just because we could not accept the trial’s verdict. The group has also always tried to find ways by which we could give something back to the world for the privilege of having shared some of our lives with those who died: how could we force something good out of something as savage and evil as this atrocity?

I had refused an opportunity to meet the two accused on one of my visits to urge Colonel Gaddafi to allow them to attend for trial. However, on observing them in court and listening to the evidence, it became increasingly clear that they might not after all be guilty. After the trial and during frequent interactions with solicitor Tony Kelly, who took over the defence team in 2005, it also became clear that those who knew Megrahi best were not simply defending a client but genuinely believed in his innocence. This, combined with news of his positive interactions with his fellow prisoners and my own growing certainty of his innocence, led me to go to see him in Greenock prison. Despite the comments of one Lord Advocate that I must be suffering from Stockholm syndrome, a friendship developed which, although it could not be as close as that of John Ashton who saw him often, became increasingly important to both of us.

I shall never forget my last visit to him as he lay dying and in great pain in Tripoli. He was still able between gasps for breath to show his concern that certain documents which he had set aside for me concerning his innocence should reach me safely after his death, which they did and have been lodged with John Ashton for safe keeping. He also repeated his concern that the curse of being ‘the bomber’s family’ should be lifted from the shoulders of his wife Aisha and the children after he had gone. I treasure having had the privilege of sharing that friendship and know that he too valued it, perhaps especially when he was still in prison and unable to see his family.

I do not know if even compassion could have empowered such a friendship for me without the knowledge of his innocence. Certainly I could not have begged Kenny MacAskill to allow the man I had come to know as Baset to go home had I still thought he was guilty. Because some others among us relatives still believed he was involved, it was a tough call to make that plea to MacAskill in the presence of one or two of them, although we knew that if he was to go home on the basis of Scotland’s provision for compassionate release, there was no obligation to stop his appeal. I leave the assessment of why Baset did withdraw his appeal to John Ashton’s book. Although I have no idea whether my plea made any difference to MacAskill’s decision, it was a privilege to be given the opportunity to make it, and I have felt some shame at the appalling and ill-informed ranting against our country and the Justice Secretary which followed Baset’s release.

That decision to use compassionate release is for me one aspect of this dreadful case about which I think Scotland should be proud, even though I cannot be sure why Baset did stop his appeal when he did not have to. The appeal would not block his release, it could have continued with him in Tripoli. Perhaps things would have gone worse for him and his family in Tripoli if his country had told him to stop the appeal as well as to come home. Knowing all we now know of the evidence that was about to be led in that appeal, it must have been a huge relief to the Crown Office that the snail’s pace of their conduct of that second appeal had allowed Baset’s cancer to catch up with him. I’ll guess that the single malts were out that evening in Chambers Street, but you won’t find such speculation as that in Ashton’s book.

It may be that the forming of this friendship is something which is intrinsically good emerging from the great evil of the atrocity. It certainly was for us both.

The doctrine of attempting to love our fellow humans is not restricted to those who believe in a God. Believers of every hue, agnostics and atheists, we all share the human predicament and we can all see the human need for help; but in no way does such an awareness free any of us from the duty of identifying wrongdoers and of sentencing them if caught, according to a tariff of punishments established by precedent and consent within the criminal law of our communities. In civilised communities justice is the surrogate for the lust for revenge, that destructive passion, which is latent in us all, and which was certainly the motive for Lockerbie.

Provided that our justice system remains objective and free from extrinsic interference it is the best route to the management of offenders, but it is also dependent upon the integrity with which the evidence is assembled, and the sharing of all the available relevant evidence for use by both prosecution and defence.

Thank God we still have some space for compassion in our justice system in Scotland, and no death penalty, so that the consequences of injustice can be diminished sometimes. But the consequences of a miscarriage of justice also ensure that the real perpetrators of a crime will be free to strike again, and other potential killers may be emboldened.

As Juvenal asked some 2,000 years ago, ‘Sed quis custodiet ipsos custodes?’ (who guards the guardians?). The refusal to date of the Scottish Government to enquire into the behaviour of their own Crown Office or individuals involved in the case, even though they unquestionably have the powers to do so, and have the findings of their Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission to guide them, as well as John Ashton’s careful analysis, is discouraging.

Scottish justice survived the Act of Union with England with its independence intact: perhaps since then it has been a talisman of Scotland’s reputation as an independent nation capable of running its own affairs. If that is so, Scotland – my country – would do well to address the apparent problem of the impenetrable arrogance of her prosecuting authorities that seem to have blighted her justice system ever since it became clear that the Lockerbie trial had been defective.

The problem must be addressed, and done so with transparency, for it will not just go away. It is best addressed from within Scotland herself and may well be a factor which will block independence until it is resolved, for an independent community with an obscured and mistrusted justice system can never be a healthy community. We would wish healing, not harm, for Scotland and all her people, but the arrogant refusal to consider fault has dragged on so long and is so great a threat now to her reputation in the world that the cure is not likely to be found within the timescale now scheduled for the independence debate. It is to be hoped that the refusal of the current Scottish government to intervene with an independent inquiry, despite clearly having the powers required to do so, is not driven by motives of party advantage. The terrible events of Lockerbie deserve far greater respect than that.

Jim Swire, 9 May 2013.

Preface

Lockerbie does not shame the Scottish people, rather it shames their two most powerful institutions: the criminal justice system and the Scottish government.

It is now 25 years since Pan Am flight 103 crashed on to the Dumfriesshire town and 12 years since Abdelbaset al-Megrahi was convicted of the bombing. This book will argue that the case has become the biggest scandal of the country’s post-devolution era. This is not because the terminally ill Libyan was released from prison, but because he should never have been charged with the murders and, still less, convicted. As a consequence of these follies the perpetrators of Europe’s worst terrorist attack went free, the 270 Lockerbie victims and their relatives were denied justice and the Libyan people were forced to endure years of devastating economic sanctions. The scandal happened because the criminal justice system failed in its most basic duties, and it has intensified because the government has continually looked the other way.

Last year my book Megrahi: You Are My Jury revealed crucial evidence that the Crown had failed to disclose to Megrahi’s defence team. Those, like Dr Jim Swire, who care about justice, were outraged, while the supposed guardians of justice ignored or condemned the book. This much shorter work is less about the fine detail of the case and more about what has gone wrong.

It is not, of course, an issue that directly affects the public’s well-being, yet many people in Scotland and beyond are concerned. That is why Megrahi received a constant stream of supportive letters and why hundreds of people will turn up to hear Dr Swire speak. It matters to them because justice matters, and in this case, justice miscarried spectacularly. It also matters because the institutions that are supposed to safeguard justice are in denial about their failure.

John Ashton, August 2013.

Flawed Charges 1

At 19.03 on Wednesday 21 December 1988, Pan Am flight PA103 broke apart over the Scottish Borders. Within minutes all 259 passengers and crew were dead, along with 11 residents of Lockerbie. The wreckage spread over 845 square miles east of the town. Forensic investigators established within days that an explosion had occurred in the forward left baggage hold. Hundreds of police officers, military personnel and volunteer searchers combed the vast crime scene for clues, while detectives investigated in Europe, the US, the Middle East, West Africa and beyond.

Almost three years later, on 14 November 1991, Scotland’s chief prosecutor, the Lord Advocate Lord Fraser of Carmyllie, and the US acting Attorney General, William Barr, simultaneously announced charges against two Libyans: Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Fhimah. The media were briefed that the bombing was Colonel Gadafy’s revenge for the 1986 US air raids on Libya.

The case appeared strong. It was alleged that on the morning of the bombing the two men placed an unaccompanied brown Samsonite suitcase on Air Malta flight KM180 from Malta to Frankfurt. The suitcase contained a bomb concealed within a Toshiba radio-cassette player and was said to be labelled for New York on PA103. At Frankfurt it was supposedly transferred to a Pan Am feeder flight, PA103A, to London Heathrow, and at Heathrow to PA103.

The suitcase was packed with clothes that Megrahi had allegedly bought in Malta on 7 December. It was claimed that he took the case from Libya to Malta on 20 December, while travelling on a coded passport under the name of Ahmed Khalifa Abdusamad. The following morning he flew back to Libya on a Libyan Arab Airlines (LAA) flight, which checked-in shortly before KM180, and somehow, with Fhimah’s help, managed to smuggle the suitcase into KM180’s baggage hold.

Police enquiries in Malta traced bomb-damaged clothes to a small shop called Mary’s House in the town of Sliema. Miraculously, shopkeeper Tony Gauci remembered selling the clothes to an oddly behaved man shortly before the Lockerbie bombing. Later to become the star witness against Megrahi, Gauci said the mystery customer was Libyan. He couldn’t recall the date of the purchase, but said it was midweek and that his younger brother Paul, who usually worked in the shop, was at home watching football on TV. Another important clue was a blast-damaged pair of brown checked trousers found at the crash site, which were made by a Maltese company, Yorkie Clothing. When the police cross-checked an order number printed on a pocket with the company’s order book, they discovered that the trousers had been delivered to the shop on 18 November 1988. When shown the TV schedules, Paul narrowed down the date to either 23 November or 7 December. Records from the Holiday Inn hotel in Sliema showed that Megrahi had stayed there on the night of 7 December.

The Malta link was confirmed by baggage records from Frankfurt airport, which appeared to show that a suitcase from Air Malta flight KM180 had been forwarded to PA103A. There was no record of any passengers transferring from KM180 to flights PA103A and PA103, and none of the victims were known to own a brown hard-sided Samsonite suitcase. The police inferred from this that the bomb suitcase – known as the primary suitcase – was unaccompanied and that it must have evaded Pan Am’s security in Frankfurt.

The explosion occurred within one of the containers that were used to store baggage in the aircraft’s holds. The containers were approximately five feet square aluminium or fibreglass-sided cubes, with an extension incorporating a 45-degree angled floor section to accommodate the curved fuselage. The bags were loaded through an open side, which was secured with a curtain when full.

The container in which the explosion occurred was aluminium and had the code number AVE4041. Forensic experts concluded that the centre of the explosion had been around 25 to 30cm above the container’s floor and had overhung the angled section by around 5cm. This, the experts claimed, meant that the primary suitcase must have been in one of the following two positions (below and next page, top).

Heathrow ground staff who loaded AVE4041 recalled that, by the time that the feeder flight PA103A arrived from Frankfurt, the bottom of the container was already covered. They said that there were five or six cases standing in a line side-on against the back wall, and two lying flat in front of them, as in the following photograph (next page, bottom).1

FIRST POSTULATED POSITION OF THE IED WITHIN THE CARGO CONTAINER

SECOND POSTULATED POSITION OF THE IED WITHIN THE CARGO CONTAINER

Approximate position of luggage before arrival of PA103A.

They had loaded the cases from PA103A on top. As the explosion appeared to have been in the second layer of luggage, it therefore seemed likely that the primary suitcase had arrived on PA103A from Frankfurt.

Megrahi appeared to be a sinister figure. Formerly head of airline security for LAA, he was alleged to be director of the Libyan Centre for Strategic Studies and a partner in a trading company called ABH. Both organizations were said to be fronts for the Libyan intelligence service, the JSO. He was related to some senior JSO figures and regularly travelled on his false Abdusamad passport.

The case against him had three key elements. The first was a fragment of electronic circuit board, which was found embedded in the collar of a blast-damaged, Maltese-made shirt. In 1990 investigators matched the fragment to an electronic timer, known as an MST-13, which was made by a Swiss company called Mebo. The company’s co-owner, Edwin Bollier, said the firm had designed and built the timers exclusively for the JSO, and that only 20 were produced. He also revealed that Mebo shared its offices with ABH. He said that in December 1988 ABH’s founder, Badri Hassan, had asked him to produce 40 more such timers for the JSO, although he had been unable to fulfill the order.

Megrahi was the common link between Bollier and Malta. There was no doubt that he had visited the island on the night of 20 December using the false passport and had flown back to Tripoli the following morning. He had also been there under his own name on 7 December, which was roughly when Gauci said he sold the clothes. Prosecutors believed that, as a former airline security chief, he would have known how to smuggle a bomb on to an aircraft and that, as LAA’s former Malta station chief, Fhimah was well placed to help him.

The second key element arrived on 15 February 1991 when Gauci picked out Megrahi’s photograph as resembling the clothes buyer. The third fell into place in July 1991, when Fhimah’s former LAA Malta deputy station chief, Majid Giaka, told the FBI that, at around the time of the disaster, Megrahi had arrived in Malta with a brown Samsonite suitcase, like the one that contained the bomb, and that Fhimah carried it through Maltese customs without it being inspected.

Apart from Giaka, the main evidence against Fhimah was his 1988 diary. A note for 15 December read: ‘Take taggs from Air Malta. OK’ and ‘Abdelbaset arriving from Zurich’, while in the back of the diary he had written: ‘Take/collect tags from the airport (Abdulbaset/Abdusalam)’. This, the prosecutors believed, showed that Fhimah had obtained an Air Malta baggage tag in order to get the suitcase on to KM180.

***

What the prosecutors knew, but failed to reveal, was what their case was full of holes. The weakest link was undoubtedly their most important witness, Tony Gauci. Remarkably, by the time the indictments were issued he had given no fewer than 18 police statements. On many matters his accounts were erratic and contradictory. On two, however, he was entirely consistent – and entirely at odds with the Crown case. The first was the weather at the time of the clothes purchase. He recalled that, as the man was about to leave the shop, he bought an umbrella as it had started to rain. At the crash site the police found the blast-damaged remains of an umbrella, which matched umbrellas sold in the shop. According to the Crown, Megrahi must have bought the clothes on 7 December 1988, as that was the only day he was in Malta. However, Maltese meteorological records obtained by the police indicated that 7 December was dry, whereas there was rain on 23 November, which was the other date on which Paul Gauci was watching football. These facts alone almost destroyed the Crown case.

The second consistent element of Gauci’s account was his description of the mystery clothes purchaser. In his first statement, dated 1 September 1989, he said: ‘He was about 6 feet or more in height. He had a big chest and a large head. He was well built but he was not fat or with a big stomach. His hair was very black . . . He was clean shaven with no facial hair. He had dark coloured skin . . . I would say that the jacket was too small for him, although it was a 42-inch size, that is British inches.’2 Megrahi, by contrast, was only 5ft 8in tall, slightly built and light-skinned.

In a further statement, on 13 September 1989, Gauci described the man as being ‘about 50 years of age’; however, at the time of the clothes purchase, Megrahi was just 36. A fortnight later Gauci told the police that the shopper had visited his shop the previous day. With the event fresh in his mind, he was able to provide the following clear description: ‘This man had the same hairstyle, black hair, no hair on his face, dark skin. He was around 6 foot or just under that in height. He was about 50 years of age. He was broad-built, not fat, and I would say he had a 36in waist.’3 Clearly, the man’s age, height and skin colour ruled out Megrahi.

When Gauci had picked out Megrahi’s photograph on 15 February 1991, he initially said none of the 12 photographs were of the man, and only chose Megrahi after being told by Detective Chief Inspector Harry Bell ‘to try and allow for any age difference’. Having picked out the photo, he told the police that Megrahi ‘would perhaps have to look about 10 years or more older and he would look like the man who bought the clothes. It’s been a long time now and I can only say that [Megrahi’s photo] resembles the man who bought the clothing, but it is younger.’

Official guidance issued to the Scottish police nine years earlier said photo line-ups should comprise people ‘of similar age and appearance’, yet most of the other 11 were younger than Megrahi, some of them considerably so. The guidance also advised that: ‘The photographs should bear no marks which would enable the witness to identify the suspect’s photograph.’4 DCI Bell had earlier noted that Megrahi’s photograph was poor quality, and had therefore asked a Maltese police photographer to re-photograph the others in order to make all twelve of similar quality.5 Despite these efforts, Megrahi’s picture stood out as being paler and grainier than the others. It was also noticeably smaller and had a series of white dots down one side and two white parallel horizontal lines.

Gauci’s description of the man as Libyan was far from certain. He said he could distinguish between Libyans and Tunisians, because the latter often reverted to French. However, as most Arabs in Malta were Libyan, many locals described them as ‘Libyanos’ regardless of their nationality.

Gauci was easily the most important Crown witness, yet Scotland’s chief prosecutor, the Lord Advocate Lord Fraser of Carmyllie – the man responsible for the indictments – harboured reservations about his reliability. Almost five years after Megrahi was convicted, and 13 years after leaving office, he told the Sunday Times