Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Kohlhammer Verlag

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

Major parts of the book of Micah were probably composed in the context of a book containing a number of prophetic writings - even as many as twelve. They can therefore only be understood and interpreted adequately within that context. That process of interpretation sheds light on an essential segment of the history of Old Testament theology: it was not primarily a matter of the statements of lone individual prophetic figures but of a common testimony to YHWH's speaking and acting in the history of his people. Zapff shows this by reflecting diachronically on the results of his synchronic exegesis and so tracing the process by which the Micah document and its theological statement were formed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 672

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament (IECOT)

Edited by:

Walter Dietrich, David M. Carr, Adele Berlin, Erhard Blum, Irmtraud Fischer, Shimon Gesundheit, Walter Groß, Gary Knoppers (†), Bernard M. Levinson, Ed Noort, Helmut Utzschneider and Beate Ego (Apocrypha/Deuterocanonical books)

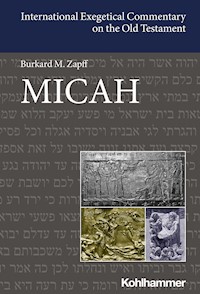

Cover:

Top: Panel from a four-part relief on the “Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III” (859–824 BCE) depicting the Israelite king Jehu (845–817 BCE; 2 Kings 9f) paying obeisance to the Assyrian “King of Kings.” The vassal has thrown himself to the ground in front of his overlord. Royal servants are standing behind the Assyrian king whereas Assyrian officers are standing behind Jehu. The remaining picture panels portray thirteen Israelite tribute bearers carrying heavy and precious gifts. Photo © Z.Radovan/BibleLandPictures.comBottom left: One of ten reliefs on the bronze doors that constitute the eastern portal (the so-called “Gates of Paradise”) of the Baptistery of St. John of Florence, created 1424–1452 by Lorenzo Ghiberti (c. 1378–1455). Detail from the picture “Adam and Eve”; in the center is the creation of Eve: “And the rib that the LORD God had taken from the man he made into a woman and brought her to the man.” (Gen 2:22)Photograph by George ReaderBottom right: Detail of the Menorah in front of the Knesset in Jerusalem, created by Benno Elkan (1877–1960): Ezra reads the Law of Moses to the assembled nation (Neh 8). The bronze Menorah was created in London in 1956 and in the same year was given by the British as a gift to the State of Israel. A total of 29 reliefs portray scenes from the Hebrew Bible and the history of the Jewish people.

Burkard M. Zapff

Micah

Verlag W. Kohlhammer

Editorial collaboration: Jonathan M. Robker

Translation: Linda M. Maloney

1. Edition 2022

All rights reserved

© W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart

Production: W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart

Print:

ISBN 978-3-17-025442-8

E-Book-Formate:

pdf: ISBN 978-3-17-025443-5

epub: ISBN 978-3-17-025444-2

All rights reserved. This book or parts thereof may not be reproduced in any form, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, microfilm/microfiche or otherwise—without prior written permission of W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart, Germany.

Any links in this book do not constitute an endorsement or an approval of any of the services or opinions of the corporation or organization or individual. W. Kohlhammer GmbH bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links.

Major parts of the book of Micah were probably composed in the context of a book containing a number of prophetic writings - even as many as twelve. They can therefore only be understood and interpreted adequately within that context. That process of interpretation sheds light on an essential segment of the history of Old Testament theology: it was not primarily a matter of the statements of lone individual prophetic figures but of a common testimony to YHWH's speaking and acting in the history of his people. Zapff shows this by reflecting diachronically on the results of his synchronic exegesis and so tracing the process by which the Micah document and its theological statement were formed.

Prof. Dr. Burkard M. Zapff is teaching Old Testament at the Catholic University Eichstätt-Ingolstadt.

Contents

Editors’ Foreword

Author’s Foreword

Introduction to the Commentary

Hermeneutical Considerations

Synchronic Analysis

Textual Basis

The Micah Document in the Book of the Twelve Prophets

The Division of the Micah Document and the Style of its Contents

Diachronic Analysis

The Origins of the Micah Document

Stage I: Starting Point of the Micah Document – The Poem of the Cities

Stage II: The Origins of the Micah Document in the Context of a Book of Several Prophets

Stage III: The Micah Document between Jonah and Nahum

The Person and Historical Background of Micah and the Micah Document

Synthesis

Theological Emphases

Reception of the Micah Document in the New Testament

Micah 1:1–7: Comes for Judgment

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 1:8–9: The Prophet’s Mourning

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 1:10–16: Disaster for the Cities of the Hill Country and Call for Lament

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 1

Micah 2:1–5: Upper-Class Intrigues and their Consequences

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 2:6–11: Prophetic Resistance to Micah

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 2:12–13: Future Salvation

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 2

Micah 3:1–4: Like Cannibals—the Machinations of the Upper Class

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 3:5–8: The False Prophets and the True Prophet of

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 3:9–12: Corruption in Zion and its Consequences

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 3

Micah 4:1–5: Zion’s Ultimate Destiny

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 4:6–8: The Gathering of those Scattered and the Kingdom of and Zion

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 4:9–14: The Troubles of the Present and the Future

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 4

Micah 5:1–5: A Future Ruler in Israel

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 5:6–8: The Remnant of Jacob among the Nations and the Destruction of Israel’s Enemies

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 5:9–13: The Cleansing of Israel from Everything Hostile to

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 5:14: ’s Judgment on the Disobedient Nations

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 5

Micah 6:1–8: ’s Expectations of His People

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 6:9–16: The Actual Behavior of Jerusalem and Its Inhabitants

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 6

Micah 7:1–7: The Prophet’s Lament and His Confidence

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Micah 7:8–20: Zion’s Assurance and its Renewal

Notes on Text and Translation

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

Internal Sequence

Detailed Exegesis

Diachronic Analysis

Synthesis of Micah 7

Bibliography

Text Editions

Reference Works

Newer Commentaries on Micah

Monographs

Articles

Index

Index of Hebrew Words

Index of Key Words

Index of Biblical Citations

Genesis

Exodus

Leviticus

Numbers

Deuteronomy

Joshua

Judges

Ruth

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

1 Kings

2 Kings

1 Chronicles

2 Chronicles

Ezra

Nehemiah

1 Maccabees

Job

Psalms

Proverbs

Song of Solomon

Sirach

Isaiah

Jeremiah

Lamentations

Ezekiel

Daniel

Hosea

Joel

Amos

Obadiah

Jonah

Micah

Nahum

Habakkuk

Zephaniah

Haggai

Zechariah

Malachi

Matthew

Luke

John

Index of Other Ancient Literature

Plan of volumes

Editors’ Foreword

The International Exegetical Commentary on the Old Testament (IECOT) offers a multi-perspectival interpretation of the books of the Old Testament to a broad, international audience of scholars, laypeople and pastors. Biblical commentaries too often reflect the fragmented character of contemporary biblical scholarship, where different geographical or methodological sub-groups of scholars pursue specific methodologies and/or theories with little engagement of alternative approaches. This series, published in English and German editions, brings together editors and authors from North America, Europe, and Israel with multiple exegetical perspectives.

From the outset the goal has been to publish a series that was “international, ecumenical and contemporary.” The international character is reflected in the composition of an editorial board with members from six countries and commentators representing a yet broader diversity of scholarly contexts.

The ecumenical dimension is reflected in at least two ways. First, both the editorial board and the list of authors includes scholars with a variety of religious perspectives, both Christian and Jewish. Second, the commentary series not only includes volumes on books in the Jewish Tanach/Protestant Old Testament, but also other books recognized as canonical parts of the Old Testament by diverse Christian confessions (thus including the deuterocanonical Old Testament books).

When it comes to “contemporary,” one central distinguishing feature of this series is its attempt to bring together two broad families of perspectives in analysis of biblical books, perspectives often described as “synchronic” and “diachronic” and all too often understood as incompatible with each other. Historically, diachronic studies arose in Europe, while some of the better known early synchronic studies originated in North America and Israel. Nevertheless, historical studies have continued to be pursued around the world, and focused synchronic work has been done in an ever greater variety of settings. Building on these developments, we aim in this series to bring synchronic and diachronic methods into closer alignment, allowing these approaches to work in a complementary and mutually-informative rather than antagonistic manner.

Since these terms are used in varying ways within biblical studies, it makes sense to specify how they are understood in this series. Within IECOT we understand “synchronic” to embrace a variety of types of study of a biblical text in one given stage of its development, particularly its final stage(s) of development in existing manuscripts. “Synchronic” studies embrace non-historical narratological, reader-response and other approaches along with historically-informed exegesis of a particular stage of a biblical text. In contrast, we understand “diachronic” to embrace the full variety of modes of study of a biblical text over time.

This diachronic analysis may include use of manuscript evidence (where available) to identify documented pre-stages of a biblical text, judicious use of clues within the biblical text to reconstruct its formation over time, and also an examination of the ways in which a biblical text may be in dialogue with earlier biblical (and non-biblical) motifs, traditions, themes, etc. In other words, diachronic study focuses on what might be termed a “depth dimension” of a given text—how a text (and its parts) has journeyed over time up to its present form, making the text part of a broader history of traditions, motifs and/or prior compositions. Synchronic analysis focuses on a particular moment (or moments) of that journey, with a particular focus on the final, canonized form (or forms) of the text. Together they represent, in our view, complementary ways of building a textual interpretation.

Of course, each biblical book is different, and each author or team of authors has different ideas of how to incorporate these perspectives into the commentary. The authors will present their ideas in the introduction to each volume. In addition, each author or team of authors will highlight specific contemporary methodological and hermeneutical perspectives—e.g. gender-critical, liberation-theological, reception-historical, social-historical—appropriate to their own strengths and to the biblical book being interpreted. The result, we hope and expect, will be a series of volumes that display a range of ways that various methodologies and discourses can be integrated into the interpretation of the diverse books of the Old Testament.

Fall 2012 The Editors

Author’s Foreword

Writing a commentary is surely one of the most demanding, but—at the same time—one of the most engaging tasks of an exegete. My approach to the book of Micah had the added circumstance that I was engaging this vital part of the Book of the Twelve Prophets for a second time, some twenty-five years after I had devoted my Habilitationsschrift to it. Since I had developed a new vision of the Book of the Twelve and its origins in the 1990’s, this gave me a chance to apply that new perspective to commenting on Micah. My thanks are due in the first instance to Helmut Utzschneider, who—himself the author of an important commentary on Micah—made it possible for my commentary to be included in the IECOT series. I am also grateful to him for some pointers that advanced my thinking. Thanks also to Florian Specker, the assistant editor at Kohlhammer for his very welcome and helpful accompaniment in the process of preparing the manuscript for publication. Further thanks are due to the colleagues in my professoriate, my assistant, Christine Schütz and the two graduate assistants, Angelika Nieslbeck and Josephine Kain, who undertook the tedious task of proofreading.

I want to dedicate this work in gratitude to my mother and my deceased father, who conveyed to me from my earliest childhood a joy in God and in Sacred Scripture.

Eichstätt, Spring 2020

Introduction to the Commentary

Hermeneutical Considerations

Purpose of the Superscription “The word of Yhwh that came to Micah of Moresheth in the days of Kings Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah of Judah, which he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem.” So reads the superscription to the Micah document with its seven chapters in its Hebrew version in what is now the Book of the Twelve Prophets. It seems to clarify the author’s name, origins, and time, and not least the object of his prophecy. Thus the superscription does what one expects of such an introduction even in modern collected volumes—and the Book of the Twelve is a great collection of different prophetic writings. It distinguishes what is to follow from the other documents and announces the author and topic.1 In fact, it has been quite common among exegetes to regard the information in this superscription as autobiographical, inasmuch as the Micah document—or the majority of it—was thought to contain the words of that prophet Micah who, in accordance with the time frame thus given, was situated in the eighth century BCE. Since we are relatively well-informed about the last third of that century, not only from biblical texts but also from other ancient Near Eastern sources, it seemed appropriate to associate Micah and his prophecy with the events of that period. This is especially the case regarding the expansion of the Neo-Assyrian empire in the Levant by means of a number of military campaigns (e.g., of the Assyrian king Sennacherib around 701 BCE). In fact, it seems that a number of Micah’s statements (especially Micah 1:8–16*) refer to a severe military threat.2 The many social-critical statements in the Micah document likewise suggest that conclusions can be drawn from Micah’s writing regarding social conditions in the Southern Kingdom in the last third of the eighth century BCE.3 Specifically, some of these social-critical statements bear striking similarity to those of the two prophets of the Northern Kingdom, Hosea and Amos, but also to the words of the prophet of the Southern Kingdom, Isaiah—who is regarded as nearly contemporary with Micah. Thus, Micah can be seen as a kind of younger colleague or disciple of Isaiah. His origins in the land—Moresheth of Gath lies in the southwestern hill country of Judah—have led to extensive biographical speculations according to which Micah may have been a kind of village elder responsible for the needs of a formerly free farming population now exploited by a greedy upper class.4 Thus the eighth-century Micah became, analogously to his colleagues of the Northern Kingdom Amos and Hosea and in company with the Southern Kingdom prophet Isaiah, the social-critical prophet of the Southern Kingdom in the eighth century BCE and—thus—a voice of Yhwh, who desired justice and righteousness. However, which words of the Micah document may actually be ascribed to the historical Micah is a question more and more hotly disputed among scholars, as in the case of the other prophetic books and writings associated with prophetic figures in the eighth century BCE. The position of Bernhard Stade acquired a powerful influence, at least in German-language scholarship. He denied that the whole second part of the Micah document (Micah 4–7) came from the eighth-century prophet.5 This is in contradistinction to large parts of English-language scholarship that tried, and still try, to allot those parts of the book to the eighth-century prophet.6 A middle position was adopted by those exegetes who wanted to ascribe at least Micah 6–7 to an anonymous prophetic figure, a “Deutero-Micah,” originally dwelling in the Northern Kingdom, whose prophecy was later joined to that of the Southern Kingdom prophet Micah from the eighth century BCE.

The fundamental problem for such an interpretation of the Micah document lies in the evaluation of the superscription, which has been and still is regarded almost as a matter of course as containing reliable historical information. It is striking, though, that the superscription not only delimits the Micah document as a separate entity within the Book of the Twelve, inasmuch as it attributes what follows to a single prophet named Micah from Moresheth, but also places these words in the context of other writings in the Book of the Twelve—especially Hosea and Amos;7 in so doing it fulfills the role proper to a superscription within a collected work. Accordingly it seems that Micah is both a younger contemporary of Hosea, the prophet of the Northern Kingdom, and also—at least from a chronological standpoint—a disciple of Amos. At the same time the date of his appearance is almost exactly congruent with that of Isaiah (Isa 1:1), so that Micah is also an exact, though somewhat younger, contemporary of Isaiah. Moreover, the list of kings reveals Deuteronomistic features and seems to be oriented to the royal list in the Deuteronomistic History. In addition, Micah’s preaching—like that of Hosea and Zephaniah—is described as “the word of Yhwh,” which reveals another common feature: that is, the superscription of Micah does not only delimit, but also links. Thus a reading of the superscription as purely biographical information is too narrow inasmuch as, by all appearances, we are dealing with a superscription that, at least in its present form, is relatively late. So the question arises whether there will also be traces of the implied correspondence among Micah, Amos, and Hosea in the content of the Micah document’s message. That in turn raises the question whether parts of the Micah document are an echo of the preaching of Hosea and Amos, so that one may rightly describe them as an expression of the one word of Yhwh in a particular time and situation.

Correlations with Hosea, Amos, and IsaiahThe present commentary seeks to pursue this line of inquiry by attending to correlations and parallels that tie the Micah document to its predecessors, the writings of Hosea and Amos. This interpretation rests in large part on the observations of recent studies concerning the origins of the Book of the Twelve, which are applied here in fresh ways.8 By starting again with the superscription we will be able to consider correspondences to Isaiah. In principle, of course, it is possible that the similarity and relatedness of Micah’s preaching to that of Isaiah are due to the Micah’s biographical proximity to Isaiah. However, should we find correspondences that reveal simultaneous links to the preaching of Isaiah, Hosea, and Amos, we will need to ask whether this does not represent a conscious dependence in the form of scribal erudition intended to make Micah correspond to the three prophets thus described. Additionally, there are texts in Micah’s pronouncements that are only intelligible to those who have already read Hosea and Amos. In such cases the question naturally arises whether the texts in question ever existed in a Micah document independent of a book containing the works of several prophets. On that basis we may ask in turn which texts within the Micah document may have existed devoid of the posited contextual relationship and thus might really be attributed to a prophet named Micah in the eighth century BCE. In contrast to a primarily biographical approach that attempts to “rescue” every possible text in the Micah document for the eighth-century prophet (indeed, to what end?) in order to deduce from them the contemporary political and social situation, this commentary will take the opposite approach. Only in the case of texts that are not related to Hosea, Amos, and Isaiah and that, moreover, reveal no exilic or postexilic character will we consider the extent to which they might be attributed to the eighth-century prophet. Some may consider such a procedure hypercritical, but what is at issue here is only the application of a principle that has proved itself in the cases of other prophetic books such as Isaiah or Amos.9 As will be demonstrated, this in no way represents a minimizing of the claims of the Micah document’s message: on the contrary, it corresponds to the tendency already evident in the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament not so much to individualize the prophetic message as to regard it as a single entity, crowned in the New Testament expressions about the (one) message of all the prophets (cf. Luke 24:25).10

Synchronic Analysis

Textual Basis

The basis for the interpretation of the Micah document offered in this commentary is the Masoretic text of Codex Lenigradensisas found in critical form in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia(BHS) and recently, with an expanded critical apparatus, in the fascicle of the Biblia Hebraica Quinta(BHQ) containing the Book of the Twelve Prophets. This text is only “corrected” when it appears necessary because of evident textual corruption or a Masoretic vocalization that seems improbable in light of the overall context.

Comparison with the SeptuagintAs a further textual basis alongside the Hebrew text transmitted and interpreted by the Masoretes, we will consider the Greek translation of the Micah document in the Septuagint (G). As a rule, the commentary will refer to the Rahlfs edition with its critical apparatus. The Greek text will not be applied to “correct” possible corruptions of the Hebrew text, but will be considered as an independent entity whose translation offers an interpretation with its own accents and emphases. In addition to our own interpretation, we will refer especially to the commentary on the German translation of G by Utzschneider in the Septuaginta Deutsch.11 Consideration and evaluation of G as an independent tradition and interpretation of the Old Testament / Hebrew Bible is not only part of recent scholarship, but it is an ecumenical desideratum inasmuch as some churches grant G (also) canonical status.12 The same is true in principle of the Syriac Bible, the Peshitta(S). Here we will use the text of Codex Ambrosianus in the critically-edited fascicle containing the Book of the Twelve Prophets and published by the Peshitta Institute of Leiden. However, given the limited length of this commentary we will consider only especially noteworthy Syriac deviations from the Hebrew or Greek text.

The Micah Document in the Book of the Twelve Prophets

The fact that the first reference in the Bible to the Twelve Prophets as a complete work with a common message (Sir 49:10),13 a conviction that is supported also by ancient text fragments that transmit the Twelve in a single scroll and not as separate books, favors the supposition that the Micah document also was meant to be understood and should be regarded not as an individual entity but in the context of the other documents of the Dodekapropheton. However, there is a problem in that the ordering of the writings in the Hebrew Bible is clearly different from that attested by G.

Location of the Micah document within the Book of the TwelveWhereas in the Masoretic tradition the Micah document follows that of Jonah, in G it appears immediately after the Hosea and Amos documents. There appear to be at least two reasons for the Masoretic order placing the Micah writing after that of Jonah: 2 Kgs 14:25 refers to a Jonah, the son of Amittai, with whom the prophet in the Jonah document is identified in Jonah 1:1. This Jonah, in turn, is said by 2 Kings to have appeared in the time of Amaziah, king of Judah, that is, in the first third of the eighth century BCE, whereas Micah from Moresheth came much later according to the chronology in Micah 1:1: namely, he proclaimed his prophecy after 756 BCE. Moreover, in its present placement in the Hebrew text the Micah document seems to play a kind of mediating role between the Jonah document with its tendency toward openness to the nations—the repentance and forgiveness of the Ninevites—and the Nahum document with its harsh words of judgment over Nineveh. It seems that Nineveh appears here as a kind of paradigm for the fundamental alternatives before which the nations stand. In fact, the Micah document distinguishes between nations that listen (Micah 1:2) and those that do not listen and are therefore subject to judgment (Micah 5:14). The placement of the Micah writing between those two documents has also left traces that can be demonstrated by redaction criticism in Micah 1:2 and Micah 7:8–20 (see below).

The Septuagint’s different placement of the Micah document within the Dodekapropheton—namely, in third place after Hosea and Amos—seems also to have its reasons. For one thing, there is the length of the Micah document, which (except for Zechariah) is the longest among the Twelve after Hosea and Amos. Besides, the chronology given in the superscription to the Micah writing names Micah as direct successor to Amos, something that, by no means least importantly (as will be shown), finds an echo in later parts of Micah’s message that are only comprehensible to someone who has previously read Hosea and Amos. It may be that this reflects an original ordering of the sequence of writings in the Book of the Twelve as it was developing. The fact that the Jonah document, in G’s ordering, appears only after Micah (and Joel) may likewise be due to the chronology of the books of Kings. Thus, 1 Kgs 22:8 mentions a Micaiah ben Imlah who appeared in the time of kings Ahab of Israel and Jehoshaphat of Judah, but the Greek version of the Micah document seems to identify that person with the eighth-century prophet Micah from Moresheth, who would accordingly have been active before Jonah ben Amittai. Such is indicated even by 1 Kgs 22:28, where the call to the nations to listen (Micah 1:2) is found on the lips of Micaiah ben Imlah. Moreover, by its mention of a spirit that causes lies to be spoken, Micah 2:11 G appears to be alluding to 1 Kgs 22:22 (see below). Finally, it seems that because of the theme of “Nineveh” the Jonah document is close to the Nahum writing, which follows it in G; that suggests a parallelization of the two documents, perhaps with the goal of relativizing the view of the Jonah document (which seems so welcoming to the nations as illustrated by the sparing of Nineveh) by means of Yhwh’s judgment on Nineveh that, according to Nahum, happens after all.

Whether following the order of the Hebrew or the Greek Bible, the Micah document in any case continues the judgment on the Northern Kingdom that emerged in Hosea and Amos; it now encompasses the Southern Kingdom as well and ends, after the destruction of the sanctuaries of the Northern Kingdom, with the devastation of Zion (Micah 3:12). Nevertheless, Micah 4:1–3 juxtaposes this with a renewal of Zion, which will not only replace the most important former sanctuary of the Northern Kingdom at Bethel but will become a new Sinai from which instruction will go forth for the nations as well (see below).

Thus, within the Book of the Twelve, the Micah document constitutes both a preliminary ending to the drama of Yhwh’s judgment over his people and a turning point and new beginning for Yhwh’s saving action that, at the same time, is open to the world of the nations. The subsequent writings are thus to be read and understood also in terms of this theological premise when they speak either of the final judgment on the nations (Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah) or of the renewal of the community of Yhwh in Jerusalem (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi) and the salvation that goes forth from it. In that sense the Micah document constitutes a kind of center and node point in the Book of the Twelve Prophets.

The Division of the Micah Document and the Style of its Contents

Outline of the Micah document according to formal criteriaA survey of the Micah document reveals various markers that can serve as anchors for an outline.14 These include the “hear, you peoples” in Micah 1:2, which has its counterpart in the reference in Micah 5:14 to the nations that do not listen. Since a second call to listen occurs in Micah 6:1, this time without concrete addressees, we might divide the Micah document into two corresponding sections: (1) Micah 1:2–5:14 and (2) Micah 6:1–7:20. The content of both sections is made up of misdeeds, judgment, and the renewal of Zion, linked by different fates for the nations: judgment by or conversion to Yhwh.

A different division emerges if we include the calls to listen in Micah 3:1 (and 3:9). Then the Micah document can be subdivided into three parts: (1) Micah 1:2–2:13; (2) Micah 3:1–5:14; (3) Micah 6:1–7:20.

Outline of the Micah document according to content criteriaA primary focus on the level of content suggests other possibilities for dividing the Micah document. It appears that judgment sayings are regularly accompanied by words about salvation. Considering that yields a threefold division: (1) Micah 1:2–2:11, calamity // Micah 2:12–13, rescue; (2) Micah 3:1–12, calamity // Micah 4:1–5:14, rescue; (3) Micah 6:1–16; 7:1–7, calamity // Micah 7:8–20, rescue. Likewise the repeated (three times) echoes of the idea of a remnant could be a division marker. Thus Micah 2:12; 4:6; and 7:18 speak of a “remnant” that will be the seed of future salvation.

Finally, we could also regard the striking shift at Micah 3:12–4:1, from the devastation of Zion to its elevation as the center of the earth, as the central division within the Micah document (and in the Book of the Twelve as a whole; cf. the Masoretes’ note at the end of Micah 3:12), and this in the sense of a transition from calamity to ultimate salvation.

These different possibilities for dividing the Micah document indicate that it probably was not composed in a single draft; rather, various hands took part in shaping it. In the process it would not have been necessary for certain arrangements, such as the sequence of calamity and rescue and the framing with the call to the nations, to be mutually exclusive. Rather, they could express different aspects, such as the perspective of Zion/Israel toward salvation and the associated and yet differentiated fate of the nations.

Style and arrangement of the contentThe style and arrangement of the content yield something like the following progression:

Micah 1:2–16 depicts a theophany of Yhwh that is directed, according to the superscription in Micah 1:1, at Samaria but that threatens to extend to Judah and Jerusalem as well (cf. Micah 1:9, 12).

Micah 2:1–11, in a first move, names the sinful behavior of the upper class that is causing trouble: they not only exploit the property of the people of the land, who are at their mercy, but forbid any kind of prophetic criticism of their actions and trust in Yhwh’s apparently unconditional promise of salvation. Such prophets of prosperity are instead portrayed by Micah as leading the people astray; moreover, the people are evidently happy to be so led.

The first promise of salvation in Micah 2:12–13 links to the threat in Micah 2:10, understood as a prediction of the exile; it promises the return of a remnant, referring to Yhwh’s former saving acts in the context of the exodus.

Micah 3:1–12 intensifies the prophet’s accusations and the resulting judgment of Yhwh. Now the evildoers of Micah 2 not only despoil those they are exploiting of their property but even deprive them of their very existence. Prophets not only tell the people what they want to hear but exploit their prophetic office to enrich themselves and to damage those who do not submit to them. Yhwh’s acts of judgment begin with these false prophets from whom Micah, as a true prophet of Yhwh, vehemently distances himself. The utterly corrupt actions of Judah’s upper class, which desecrates Zion, lead to the devastation of Mount Zion.

As Micah 2:12–13 juxtaposed a prophecy of salvation to the threatening words in Micah 2:10 (understood as a threat of exile), so Micah 4:1–4 follows the devastation of Zion in Micah 3:12 with the elevation of Zion to become the center of the world of all nations. This is followed in Micah 4:6–8 with another promise of salvation in the form of a gathering and restoration of the remnant of Jacob and the enduring rule of Yhwh.

That in turn is contrasted, in Micah 4:9–14, with the pitiful present state of Zion, which suffers above all from the absence of a king, or of royal rule, and is oppressed by the nations.

Micah 5 links the return of royal rule in various forms (renewal of individual kingship in Micah 5:1–3; kingship of the remnant of Jacob in the midst of the nations in Micah 5:6–7) to a final purifying judgment of Zion in Micah 5:9–13 and judgment on the nations that are unwilling to listen in Micah 5:14.

Micah 6 sets Yhwh’s saving acts in the past (Micah 6:1–5) over against Israel’s misbehavior (Micah 6:9–16) and formulates Yhwh’s expectations of each individual in Israel and the nations (Micah 6:6–8).

Finally, in Micah 7:1–17 the starting point is trust in Yhwh, which the prophet exemplifies in view of the overall chaos in society. Its acceptance by Zion, which at the same time admits its guilt, leads to the fall of its enemy (called “she”) or the conversion of the nations to Yhwh.

The Micah document ends in Micah 7:18–20 with a hymnic conclusion that stresses Yhwh’s fidelity and readiness to swear unswerving loyalty. Thus the drama of the Micah document leads to a good ending.

There are, in fact, tendencies in recent scholarship to point out dramatic elements in the Micah document.15 After what has just been said, one should avoid viewing the Micah document as a solitary unit, but should see it instead as both a preliminary conclusion and a climax to the preceding books of Hosea and Amos and also as a marked point of passage to the writings in the Book of the Twelve that follow. Thus, as a whole, what we are dealing with in the Micah document—in view of the whole collection of books—is an important segment of the great drama involving Zion, Israel, and the nations.16

Diachronic Analysis

The Origins of the Micah Document

A review of the Micah document reveals a whole series of fractures and inconsistencies in the content. A classic example is Micah 2:12–13, which has been and is read very differently throughout the history of scholarship and also in the interpretation of G. Readings vary between a saving word from the lips of Micah or—in contrast to his preceding words of warning in Micah 2:8–10—a saving word on the lips of his opponents, who speak to the people in imitation of the words in Micah 3:11; or else it is read as a word of warning in continuation of Micah’s proclamation of judgment. Therefore, depending on one’s interpretation, Micah 2:12–13 can be seen either as an integral part of the prophet’s original message or as a later expansion. Likewise, the different possibilities for interpreting the Micah document, listed above, point to a literary history of the book that probably moved through several stages. Since the various sections of this commentary will undertake a detailed literary- and redaction-critical examination of the Micah document it will suffice here to sketch the basic lines of the Micah document’s origins. One important insight from the history of research is that the Micah document contains a number of texts whose motifs and semantics reveal features associated with exilic and postexilic texts. On the basis of such observations Stade proposed that authentic texts that could be attributed to the eighth-century prophet Micah are to be found only in Micah 1–3 (see above). Micah 3:12 seems to offer a foundation for this observation; there, Micah is unquestionably characterized as a prophet of judgment, and this is evident from a supposedly authentic quotation in Jeremiah 26:18. In contrast, Micah 4 and 5 are exilic or postexilic additions corresponding to texts in the book of Isaiah. Finally, Micah 6–7 are seen as a separate entity that may originally have been independent of the Micah document; it is sometimes attributed to a “Deutero-Micah” from the Northern Kingdom.

However, a closer examination shows that large parts of Micah 1–3 presuppose a reading of the Hosea and Amos documents. In addition, the separation between Micah 3:12 and Micah 4:1–3 is not as radical as one might suppose at first glance. There are also references to Hosea and Amos in Micah 4/5 and 6/7. In turn, Isaian theology is to be found not only in Micah 4 and 5 but also in Micah 1–3 and 7. In Micah, 1–3 these references are also inextricably bound up with references to Hosea and Amos. Finally, as we have said, Micah 1 and 7 reveal a series of correspondences with the preceding Jonah document and the subsequent Nahum document. Only Micah 1:8, 10–16* constitutes a highly independent entity within the Micah document and reveals no contacts with or knowledge of the writings just named. If we take these contacts as the basis for a redaction-critical model we can recognize the following line of development.

Stage I: Starting Point of the Micah Document – The Poem of the Cities

The starting point for the Micah document seems to have been some individual sayings of Micah. These are found primarily in the poem of the cities in Micah 1:8, 10–16*, which evidently describes an Assyrian attack on cities in the hill country with Jerusalem as its goal. At most there is a distant similarity in form and content to Isaiah 10:28–34. In addition, some social-critical sayings, especially in Micah 2 and 3, seem to be traceable to the eighth-century prophet, but in their present form they have either been completely worked into their context and augmented with references to Hosea and Amos and/or associated with similar sayings from Isaiah. These few fragments suggest that there was no Micah document in the strict sense of the word from the eighth century BCE but merely, besides the poem of the cities, a few more or less brief sentences from the historical Micah that have been passed down.

Stage II: The Origins of the Micah Document in the Context of a Book of Several Prophets

In my opinion there was, from the outset, a Micah document that was the basis for the current one, originating in the context of the writings of Hosea and Amos with the goal of extending their message of judgment to the Southern Kingdom but not stopping there. Instead it developed a prospect of salvation for Zion at the same time. Simultaneously, Micah—based on its dating to the eighth century BCE—was accepted and styled as the work of a contemporary colleague of Isaiah. That, in turn, means that there never was a Micah document lacking Micah 4:1–3, 4 and 5:9–13, the two texts linked by Isaiah 2:2–5, 6–7. Since Micah 6:1–16 testifies also to the connection with Hosea and Amos and the transfer of the sins of the Northern Kingdom to the Southern (according to Micah 1:9), it seems that those chapters were also part of the original content of that Micah document. Evidently it originally contained Micah 1:1, 3–16*; 2:1–11*; 3:1–12; 4–5*; 6:1–16.

A unique editing in Micah 4:8; 5:1–3, linking to Micah 4:4, is devoted to the theme of “kingship” and thus anticipates a human figure who will function as vicar of Yhwh’s royal rule.

Stage III: The Micah Document between Jonah and Nahum

Another comprehensive expansion relates the Micah document to those of Jonah and Nahum; it speaks of the return of the Diaspora and describes the future relationship to the nations in royal terminology so that it is only the remnant of Jacob, in collective form, that assumes the place of the ruler in Micah 5:1 (cf. Micah 5:6–7). A judgment on the disobedient nations in Micah 5:14 links with a conversion of the nations and the fall of Zion’s enemies. This, in turn, prepares for the theme of the Nahum document that follows, while the themes of the Jonah document are found not only in the conversion of the nations in Micah 7:17 but also in the submersion of the sins of the remnant of Jacob (rather than the prophet) in the depths of the sea. This continuing level includes Micah 1:2; 2:12–13; 4:6–7; 4:9–13*; 5:6–7, 8, 14; 7:1–20.

The three stages so briefly sketched here obviously do not exclude isolated additions and continuations of the Micah document.

The Person and Historical Background of Micah and the Micah Document

First of all, we must draw a fundamental distinction between the prophet Micah from the eighth century BCE, to whom the superscription of the Micah document attributes its composition, and the figure and message of the prophet as we can derive them from the texts of today’s canonical Micah. As we have shown, this is the fruit of a long process of continuation and interpretation that essentially came to an end only with the completion of the Book of the Twelve Prophets and its canonization in the Hebrew Bible. It even experienced a continuation in the ancient translations of the Septuagint and the Peshitta. Neither of the latter can be understood simply as translations in the modern sense; they each combine the process of translation with the application of their own individual interpretive viewpoint. To that extent the various forms of the Micah document only allow very limited conclusions about the proclamations of the prophet Micah from the eighth century BCE.

Period of Micah’s preachingThe period designated for Micah’s preaching in the superscription encompasses approximately the period between 744 and 696 BCE, or about fifty years. Since, moreover, for theological reasons this statement correlates with the period of Amos’s preaching and because—among other reasons—its dependence on Deuteronomistic chronology and formulations points to a later period, very little historical authority can be attributed to it. At most it allows us to say that a prophet called Micah appeared at some point in the last third of the eighth century BCE and that this prophet stemmed from the southwestern hill country adjoining the Judean highlands that were dominated by the second-largest fortress in Judea, Lachish. The proximity to the coastal plain, dominated by the important military and commercial road between Egypt and Mesopotamia running through it, made it inevitable that this region was touched much earlier and more extensively by the expansion of the Assyrian Empire in that period than was Jerusalem, the royal capital of the southern kingdom of Judah, with its location farther inland.

Political situationConsequently the list of cities in Micah 1:9–16* appears to point to an Assyrian military campaign directed against Hezekiah, ruler of the Southern Kingdom, who according to information from both biblical and contemporary sources (cf. the Sennacherib Prism) was striving to escape from the vassal relationship to the Assyrian king that his predecessor Ahaz had evidently entered (cf. 2 Kgs 16:7). It appears that in this context a series of Judahite cities and localities, not least Lachish, were seriously affected. The campaign climaxed with a siege of Jerusalem, which—for reasons that can no longer be accurately reconstructed by historians—was spared occupation (cf. 2 Kgs 18:13–19:37). It remains unclear to what extent Micah himself reckoned with a threat to Jerusalem, or whether he only described the actual Assyrian movements and the account was then later extended in the Babylonian period under the influence of subsequent events. That is a question that remains open.

Social critiqueBeyond this, the Micah of the eighth century BCE appears to have presented himself as a social-critical prophet inasmuch as he critiqued the social imbalance in the Southern Kingdom, in which, evidently, the previously free rural population was being pauperized and reduced to debt slavery by the machinations of an unscrupulous upper class. Here also the texts seem to have experienced additions and reinterpretations that secured its timeliness even at later dates and in altered situations extending into the postexilic period. This is especially true as regards the theological development of the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem within the context of Babylonian expansion and the subsequent exile of major parts of the upper class of Judah and Jerusalem in 586 BCE. In that context the preexilic prophets were seen as proclaiming Yhwh’s judgment, provoked by the unjust conditions in both Northern and Southern Kingdoms. The preaching of the preexilic Micah, which survives only in very fragmentary form, was then incorporated into an all-encompassing historical event reflecting the fall of Samaria and the devastation of Zion. This devastation, however, became the starting point for a fundamental renewal that, beginning with Deutero-Isaiah’s prophecy of salvation, was anticipated in the Persian era. Major parts of today’s Micah document may have been composed during that period. The conclusion is an addition probably extending into Hellenistic times and more particularly reflecting the relationship between Israel and the nations. Micah now becomes the proclaimer of a division within the world of all nations whereby those nations that obey receive salvation while the disobedient ones are threatened with destruction. Here it appears that Micah’s prophecy has been accommodated to other prophetic writings in the developing Book of the Twelve, especially Zechariah. That might have occurred in the course of the final redactions of the Book of the Twelve, if not earlier; there are similarities to comparable processes in the editing of the book of Isaiah (cf. Micah 7 and Isa 12:1–6). Thus the Micah document reflects a theological-historical development, one which had its starting point in the prophetic words of an eighth-century BCE prophet whose historical origins are difficult to detect, but the development of which extended into the Hellenistic period within the framework of the emerging Book of the Twelve. In the process the individual profile of the prophet gradually vanished as it became that of a person who preached the one word of Yhwh for a particular period. In the process, in fact, the Micah document thus underwent “time travel,” apparently being shaped more or less from the beginning as a kind of “group excursion” of a book of several prophets, later a Book of Twelve.

Synthesis

Theological Emphases

The following theological themes play a prominent role in the Micah document:

Social critiqueLike the writings of Hosea and Amos, the Micah document reveals a whole series of social-critical texts. Their focus is on members of the upper class who are exploiting the previously free rural population, acquiring their fields and property, and driving their families from their homes. We may probably perceive in the background the ancient law of debt, which allowed for seizure of the property, persons, and families of the debtor when liabilities exceeded assets. In this way, the Micah document illustrates how the social crimes of the upper class, criticized especially in Amos regarding the situation in the Northern Kingdom, have now extended to the Southern Kingdom. Isaiah is a second witness to this.

Theological interpretation of the destruction of Jerusalem and the exileAs in the Amos document, here also social sins serve as the reason for the loss of the land, the exile, and ultimately for the destruction of the sanctuary that no longer serves as a temple for Yhwh. In this way Yhwh shows himself to be a God who demands unconditional righteousness and whose worship cannot be separated from the creation of just social conditions.

Zion as central sanctuary and new Sinai Another theological focus is the theology of Zion developed in the Micah document. It shows that the theologians engaged here are at home in the traditions of the Southern Kingdom. In contrast to the sanctuaries of the Northern Kingdom, which are evidently regarded as illegitimate, Zion experiences a purification through judgment that not only enables it to replace the former sanctuary of the Northern Kingdom at Bethel and become a new Sinai but, at the same, time makes it the center of the world to which the nations will make pilgrimage. There can be no doubt that Yhwh thereby becomes not only the unique God of Israel but also of the world of all nations. Thus, a monotheistic ideology is embedded here—at least between the lines. The various enemies of Zion and thus of the God of Israel must fall; in contrast, those who orient themselves to Zion will receive the blessing of the God of Israel.

Salvation and calamity for the nationsThis Zion theology is combined with a theology of the nations that reflects not only the relationship between the nations and Israel but also the future destiny of those peoples as determined by their attitude toward Zion. At the same time, the remnant of Jacob in the midst of the nations will exercise its royal rule for the benefit or detriment of the nations. Both aspects—located at the center of the Book of the Twelve—thus represent a key statement. In fact both themes, often inextricably intertwined, play an important role in the subsequent writings included in the Book of the Twelve Prophets.

Ethical individualizing and universalizingThe theme of the nations is also connected with a kind of universalizing and individualizing of ethical actions when many nations orient themselves to Yhwh’s instruction that goes forth from Zion or, as in Micah 6:8, there is a formulation of the way of life God expects of all people and of each individual.

Kingship in IsraelFinally, the theme of “kingship” plays an important role in the Micah document. Interestingly, it is not defined in a particular way; it shifts between the kingship of Yhwh, the kingship of Zion, the raising up of an individual royal figure echoing the tradition of David and Solomon, and ultimately the remnant of Jacob, which is endowed with royal attributes. Differently from older traditions, the concept of kingship is thus thought of not in alternatives but in complements: Yhwh’s kingship—and Zion’s participation in it—is the expression of universal rule. The kingship of the one awakened by Yhwh is for the liberation and protection of Israel, while Israel’s kingship in turn can work for the well-being and woe of the nations.

Reception of the Micah Document in the New Testament

The New Testament contains references or allusions to the Micah document in 21 passages.17 Most of these are allusions. Some of these, like John 7:42, which adopts the reference text in Micah 5:1 , follow the text more or less in its original sense. However, for the most part, the Micah texts simply serve as a linguistic space within in which the author formulates freely (thus, e.g., in the Magnificat at Luke 1:74, with reference to Micah 4:10). Three or four New Testament passages, however, contain direct quotations from the Micah document: Matthew 10:(21), 35–36; Luke 12:53 (Micah 7:6), and Matthew 2:6 (Micah 5:1). The last of these texts is the only one to attribute the quotation explicitly to “the prophet” (διὰ τοῦ προφήτου) without naming him specifically. Here again we find the tendency already alluded to, namely, to de-individualize Old Testament prophecy to some extent and to regard it as a single message. The adoption of this citation is a sign that the birth of Christ is regarded as the fulfillment of this prophetic promise even though on the lips of the scribe who cites it there is no formula of fulfillment. This indicates an anti-Jewish sharpening of the text: “although the scribes of the people of God recognize that they are talking about the hoped-for messianic shepherd of God’s people Israel, [they do not act] on that knowledge …”18 While in Jewish reception the divisions spoken of in Micah 7:6 refer to the time before the coming of the Messiah, in Matthew 10:35–36 “they are connected with the coming of Christ. It is precisely the mission of Christ that will bring the horrors of the eschaton.”19 Differently from Matthew, who adopts the Micah quotation literally, Luke 12:53 simply draws inspiration from it inasmuch as here the old and the young stand up against each other; Luke relates these conflicts to the plagues of the end times, thus adopting a topos also found in Jewish apocalyptic. François Bovon, in turn, interprets Jesus’s and the Christian communities’ adoption of that topos in terms of the rupture caused by the establishment of a new community in accord with his message and sees it as reflecting the personal, cultic, and patriotic issues of the present.20 It continued to echo in the first Christian textual witnesses containing an echo of the division within families.

It is striking, in any case, that Micah’s social critique, which runs through a significant part of his writing, enjoyed no reception in the New Testament. For that very reason, nonetheless, the Micah document may be the decisive message for a modern reader for whom its words have lost none of their currency in light of the exploitative structures in our world, some of them systemic, and the associated marginalization of a major part of the world’s population. In continuing Christian reception, the Church Fathers in particular accepted the Micah document as a Christian writing and interpreted it accordingly.21

Micah 1:1–7: Yhwh Comes for Judgment

1:1 The word of the Lord

that camea to Micah of Moresheth

in the days of Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, the kings of Judah, whatb he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem.

2 Hear, you peoples, all of them!a

listen, O earth, and all that is in it;

and let the Lord Yhwh be a witness against you,b

the Lord from his holy temple.c

3 For lo, Yhwh is coming out of his place,

and comes down and treads upon the high places of the earth.

4 and the mountains will melta under him

and the valleys will burst open,b

like wax near the fire,

like waters poured down a steep place.

5 All this [is happening] for the transgression of Jacob

and for the sins of the house of Israel.

Whoa is the transgression of Jacob?

Is it not Samaria?

And who are the heights of Judah?b

Is it not Jerusalem?

6 And I will make Samaria

a heap of ruins in the open country,

for the planting of vineyards,a

and I will pour down her stones into the valley,

and uncover her foundations.

7 All her images shall be beaten to pieces,a

all her gifts shall be burned with fire,a

and all her idols I will lay waste;

for as the wages of a prostitute she [Samaria] gatheredb them,

and as the wages of a prostitute they shall again be used.

Notes on Text and Translation

1a G deprives Micah 1:1 of its character as a superscription by setting the verse within a narrative context: “And it came to pass … (καἰ ἐγένετο); cf. Jonah 1:1 G.

1b The context of the second relative particle אשׁר depends on how one understands the following “saw.” G sees the root as absolute and referring to the kings just named: “whom he saw concerning Samaria and Jerusalem.” But the comparable passage in Isa 2:1 suggests a reference to a preceding object, namely, “word” (cf. V, “quod videt”).

2a The address to the nations is in tension with “all of them” (S: “all of you,” but cf. 2 Chr 18:27). It is possible that what we have here is a “stylistic device”1 whose purpose is, on the one hand, to address the nations and, on the other hand, at the same time to shift attention to the real addressees. The latter are meant to be those in the Jerusalem community who hear the word so that then the nations can be spoken about.

2b When G translates “among you” (ἐν ὑμιν). Yhwh is giving witness to a universal audience. But Num 5:13; Deut 19:16, and Prov 24:28 show that עד in a construction with ב should be understood in the sense of a testimony “against” someone.2

2c G renders “holy temple” with “holy house” (έξ) οἴκου ἁγίου, thus creating a connection to Micah 4:2 G.3

4ab G translates in v. 4aα “(the mountains) will quake,” σαλευθήσεται, and in v. 4b “(the valleys) will melt,” τακήσονται, thus making the two images in v. 4b explications of v. 4aβ.

5a The use of the interrogatory particle “who,” making the two cities appear as personal entities, is striking (contrary to 1QpMi/S: “what?”).

5b G translates “house of Judah,” οἴκου Ιούδα, thus creating a correspondence to “house of Israel” in v. 5aβ.

6a The common translation “for planting vineyards” does not seem to make sense, because vineyards have an entirely positive connotation in the OT / HB. It is probably better to read the preposition ל as describing the purpose in the sense of “for the planting of vineyards.”4 G translates “storehouse for fruits of the field,” εἰς ὀπωροφυλάκιον ἀγρου (cf. v. 5), using the same concept that describes disgraced Zion in Isa 1:8 G and in Micah 3:12 G (“garden-watcher’s hut).5

7a The passive forms in v. 7aαβ are rendered actively in G: “they cut to pieces” / “they burn.” The Samaritans would then be the probable subject; they rid themselves of their idols. This may form a link to Micah 4:36 (“beating” swords into plowshares).

7b T/S avoid the change of subject and presume קֻבָּצָוּ, “they were gathered.”

Synchronic Analysis

Contextuality

The content of the opening chapter of the Micah document represents the proclamation of a judgment by Yhwh that at first applies only to Samaria but then extends to Jerusalem, or more generally to the cities and villages in the Judean hill country. It is true that the writings of the Book of the Twelve Prophets preceding the Micah document—according to the Masoretic order—are already in place, and in them the proclamation of Yhwh’s judgment on the Northern Kingdom and its metropolis, Samaria, is already accompanied by a judgment on Judah (cf., e.g., Amos 2:4–5), but only in the Micah document do we find an explicit link between the two themes, ultimately resolving into an extended demonstration of the guilt of Zion and its inhabitants (Micah 3:12).

Linking the fates of Samaria and JerusalemOne might accordingly suppose that in the present context of the (Hebrew) Book of the Twelve the Micah document takes up the theme of Samaria that was already treated in Hosea and Amos and now links it to the theme of Zion, so that Yhwh’s judgment on the Northern Kingdom finds its continuation in a judgment on the Southern Kingdom and Zion, its metropolis. The superscription to the Micah document also reflects such a joining of the themes of Samaria and Zion (cf. Micah 1:1). Moreover, that very superscription corresponds closely, both in form and content, to the superscriptions of Hosea, Amos, and Zephaniah. And it links with their chronology to the extent that it describes a period of time when Micah appeared, connects it to Amos’s activity, and parallels it to that of Hosea. From that the question also arises whether the Micah document in its present form was and is meant to be read not only in the context—or even more precisely, in continuity—with those three documents.

Correspondence with the book of Isaiah