11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

In hidden catacombs beneath London, below the royal court of Elizabeth I, a second queen holds power. Invidiana, the dark ruler of faerie England. Fae and mortal politics have become inextricably entwined, in alliances and betrayals. When the faerie Lune is sent to manipulate Elizabeth's spymaster, her path crosses that of a mortal agent, Michael Deven, who is seeking the hidden hand in English politics. Will they be able to find the source of Invidiana's power? Find it, and break it...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Marie Brennan

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Act One

Act Two

Act Three

Act Four

Act Five

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Marie Brennan and available from Titan Books

THE MEMOIRS OF LADY TRENT

A Natural History of Dragons

The Tropic of Serpents

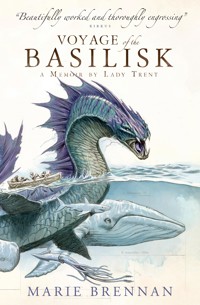

Voyage of the Basilisk

In the Labyrinth of Drakes (April 2016)

ONYX COURT

In Ashes Lie (June 2016)

A Star Shall Fall (September 2016)

With Fate Conspire (January 2017)

Midnight Never Come

Print edition ISBN: 9781785650734

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785650741

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: November 2015

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 2008, 2015 by Marie Brennan. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

This book is dedicated to two groups of people.

To the players of Memento: Jennie Kaye, Avery Liell-Kok, Ryan Conner, and Heather Goodman.

And to their characters, whose ghosts still haunt this story: Rowan Scott, Sabbeth, Erasmus Fleet, and Wessamina Hammercrank.

PROLOGUE

The Tower of London: March 1554

Fitful drafts of chill air blew in through the cruciform windows of the Bell Tower, and the fire did little to combat them. The chamber was ill lit, just wan sunlight filtering in from the alcoves and flickering light from the hearth, giving a dreary, despairing cast to the stone walls and meagre furnishings. A cheerless place—but the Tower of London was not a place intended for cheer.

The young woman who sat on the floor by the fire, knees drawn up to her chin, was pale with winter and recent illness. The blanket over her shoulders was too thin to keep her warm, but she seemed not to notice; her dark eyes were fixed on the dancing flames, morbidly entranced, as if imagining their touch. She would not be burned, of course; burning was for common heretics. Decapitation, most likely. Perhaps, like her mother, she would be permitted a French executioner, whose sword would do the work cleanly.

Presuming the Queen’s mercy permitted her that consideration. Presuming the Queen had mercy for her at all.

The few servants she kept were not there; in a rage she had sent them away, arguing with the guards until she won these private moments for herself. As much as solitude oppressed her, she could not bear the thought of companionship in this dark moment, the risk of showing her weakness to others. And so when she waked from her reverie to sense another in the room, her anger rose again. Shedding the blanket, the young woman whirled to her feet, ready to confront the intruder.

Her words died, unspoken, and behind her the fire dipped low.

The woman she saw was no serving-maid, no lady attendant. No one she had ever seen before. A mere silhouette, barely visible in the shadows—but she stood in one of the alcoves, where a blanket had been tacked up to cover the arrow-slit window.

Not by the door. And she had entered without a sound.

“You are the Princess Elizabeth,” the woman said. Her voice was a cool ghost, melodious, soft, and dark.

Tall, she was, taller than Elizabeth herself, and more slender. She wore a sleek black gown, close-fitting through the body but flaring outward into a full skirt and a high standing collar that gave her presence weight. Jewels glimmered with dark colour here and there, touching the fabric with elegance.

“I am,” Elizabeth said, drawing herself up to the dignity of her full height. “I have given no orders to accept visitors.” Nor was she permitted any, but in prison as in court, bravado could be all.

The stranger’s voice answered levelly. “I am not a visitor. Do you think this solitude your own doing? The guards allowed it because I arranged that they should. My words are for your ears alone.”

Elizabeth stiffened. “And who are you, that you presume to order my life in such fashion?”

“A friend.” The word carried no warmth. “Your sister means to execute you. She cannot risk your survival; you are a focal point for every Protestant rebellion, every disaffected nobleman who hates her Spanish husband. She must dispose of you, and soon.”

No more than Elizabeth herself had already calculated. To be here, in the stark confines of the Bell Tower, was an insult to her rank. Prisoner though she was, she should have received more comfortable lodgings. “No doubt you come to offer me some escape from this. I do not, however, converse with strangers who intrude on me without warning, let alone make alliances with them. Your purpose might be to lure me into some indiscretion my enemies could exploit.”

“You do not believe that.” The stranger came forward one step, into a patch of thin, grey light. A cruciform arrow-slit haloed her as if in painful mimicry of Heaven’s blessing. “Your sister and her Catholic allies would not treat with one such as I.”

Slender as a breath, she should have been skeletal, grotesque, but far from it; her face and body bore the stamp of unearthly perfection, a flawless symmetry and grace that unnerved as much as it entranced. Elizabeth had spent her childhood with scholars for her tutors, reading classical authors, but she knew the stories of her own land, too: the beautiful ones, the Fair Folk, the Good People, whose many epithets were chosen to mollify their capricious natures.

The faerie was a sight to send grown women to their knees, and Elizabeth was only twenty-one. Since childhood, though, the princess had survived the tempests of political unrest, riding from her mother’s inglorious downfall to her own elevation at her brother’s hands, only to plummet again when their Catholic sister took the throne. She was intelligent enough to be afraid, but stubborn enough to defy that fear, to cling to pride when nothing else remained.

“Do you think me easier to cozen than my sister? Some say your kind are fallen angels, or in league with the devil himself.”

The woman’s laugh echoed from the chamber walls like shattering crystal. “I do not serve the devil. I offer you a bond of mutual aid. With my help, you may be freed from the Tower and raised to your sister’s throne. Your father’s throne. Without it, your life will surely end soon.”

Elizabeth knew too much of politics to even consider an offer without hearing it in full. “And in return? What gift—no doubt a minor, insignificant trifle—would you require from me?”

“Oh, ’tis not minor.” The faintest of smiles touched the stranger’s lips. “As I will raise you to your throne, you will raise me to mine. And when we both achieve power, perhaps we will be of use to each other again.”

Every shrewd instinct and fibre of caution in Elizabeth warned her against this pact. Yet over her hovered the spectre of death, the growing certainty of her sister’s bitterness and hatred. She had her allies, surely enough, but they were not here. Could they be relied upon to save her from the headsman?

To cover her thoughts, she said, “You have not yet told me your name.”

The fae paused. At last, her tone considering, she said, “Invidiana.”

When Elizabeth’s servants returned soon after, they found their mistress seated in a chair by the fire, staring into its glowing heart. The air in the chamber was freezing cold, but Elizabeth sat without cloak or blanket, her long, elegant hands resting on the arms of the chair. She was quiet that day, and for many days after, and her gentlewomen worried for her, but when word came that she was to be permitted to walk at times upon the battlements and to take the air, they brightened. Surely, they hoped, their futures—and that of their mistress—were looking up at last.

ACT ONE

Time stands still with gazing on her face, stand still and gaze for minutes,houres and yeares, to her giue place: All other things shall change,but shee remains the same,till heauens changed haue their course & time hath lost his name.

JOHN DOWLANDTHE THIRD AND LAST BOOKE OF SONGS OR AIRES

No footfalls disturb the hush as the man—not nearly so young as he appears—passes down the corridor, floating as if he walks on the shadows that surround him.

His whisper drifts through the air, echoing from the damp stone of the walls.

“She loves me… she loves me not.”

His clothes are rich, thick velvet and shining satin, black and silver against pale skin that has not seen sunlight for decades. His dark hair hangs loose, not disciplined into curls, and his face is smooth. As she prefers it to be.

“She loves me… she loves me not.”

The slender fingers pluck at something invisible in his hands, as if pulling petals from a flower, one by one, and letting them fall, forgotten.

“She loves me… she loves me not.”

He stops abruptly, peering into the shadows, then reaches up with one shaking hand to touch his eyes. “She wants to take them from me, you know,” he confides to whatever he sees—or thinks he sees. Years in this place have made reality a malleable thing to him, a volatile one, shifting without warning. “She spoke of it again today. Taking my eyes… Tiresias was blind. He was also a woman betimes; did you know that? He had a daughter. I have no daughter.” Breath catches in his throat. “I had a family once. Brothers, sisters, a mother and father… I was in love. I might have had a daughter. But they are all gone now. I have only her, in all the world. She has made certain of that.”

He sinks back against the wall, heedless of the grime that mars his fine clothing, and slides down to sit on the floor. This is one of the back tunnels of the Onyx Hall, far from the cold, glittering beauty of the court. She lets him wander, though never far. But whom does she hurt by keeping him close—him, or herself? He is the only one who remembers what this court was, in its earliest days. Even she has chosen to forget. Why, then, does she keep him?

He knows the answer. It never changes, no matter the question. Power, and occasional amusement. These are the only reasons she needs.

“That which is above is like that which is below,” he whispers to his unseen companion, a product of his fevered mind. “And that which is below is like that which is above.” His sapphire gaze drifts upward, as if to penetrate the stones and wards that keep the Onyx Hall hidden.

Above lies the world he has lost, the world he sometimes thinks no more than a dream. Another symptom of his madness. The crowded, filthy streets of London, seething with merchants and labourers and nobles and thieves, foreigners and country folk, wooden houses and narrow alleys and docks and the great river Thames. Human life, in all its tawdry glory. And the brilliance of the court above, the Tudor magnificence of Elizabetha Regina, Queen of England, France, and Ireland. Gloriana, and her glorious court.

A great light, that casts a great shadow.

Far below, in the darkness, he curls up against the wall. His gaze falls to his hands, and he lifts them once more, as if recalling the flower he held a moment ago.

“She loves me…

“…she loves me not.”

RICHMOND PALACE, RICHMOND

17 September 1588

“Step forward, boy, and let me see you.”

The wood-panelled chamber was full of people, some hovering nearby, others off to the side, playing cards or engaging in muted conversation. A musician, seated near a window, played a simple melody on his lute. Michael Deven could not shake the feeling they were all looking at him, openly or covertly, and the scrutiny made him unwontedly awkward.

He had prepared for this audience with more than customary care for appearances. The tailor had assured him the popinjay satin of his doublet complemented the blue of his eyes, and the sleeves were slashed with insets of white silk. His dark hair, carefully styled, had not a strand out of place, and he wore every jewel he owned that did not clash with the rest. Yet in this company, his appearance was little more than serviceable, and sidelong glances weighed him down to the last ounce.

But those gazes would hardly matter if he did not impress the woman in front of him.

Deven stepped forward, bold as if there were no one else there, and made his best leg, sweeping aside the edge of his half-cloak for effect. “Your Majesty.”

Standing thus, he could see no higher than the intricately worked hem of her gown, with its motif of ships and winds. A commemoration of the Armada’s recent defeat, and worth more than his entire wardrobe. He kept his eyes on a brave English ship and waited.

“Look at me.”

He straightened and faced the woman sitting beneath the canopy of estate.

He had seen her from afar, of course, at the Accession Day tilts and other grand occasions: a radiant, glittering figure, with beautiful auburn hair and perfect white skin. Up close, the artifice showed. Cosmetics could not entirely cover the smallpox scars, and the fine bones of her face pressed against her aging flesh. But her dark-eyed gaze made up for it; where beauty failed, charisma would more than suffice.

“Hmmm.” Elizabeth studied him frankly, from the polished buckles of his shoes to the dyed feather in his cap, with particular attention to his legs in their hose. He might have been a horse she was contemplating buying. “So you are Michael Deven. Hunsdon has told me something of you—but I would hear it from your own lips. What is it you want?”

The answer was ready on his tongue. “Your Majesty’s most gracious leave to serve in your presence, and safeguard your throne and your person against those impious foes who would threaten it.”

“And if I say no?”

The freshly starched ruff scratched at his chin and throat as he swallowed. Catering to the Queen’s taste in clothes was less than comfortable. “Then I would be the most fortunate and most wretched of men. Fortunate in that I have achieved that which most men hardly dream of—to stand, however briefly, in your Grace’s radiant presence—and wretched in that I must go from it and not return. But I would yet serve from afar, and pray that one day my service to the realm and its glorious sovereign might earn me even one more moment of such blessing.”

He had rehearsed the florid words until he could say them without feeling a fool, and hoped all the while that this was not some trick Hunsdon had played on him, that the courtiers would not burst into laughter at his overblown praise. No one laughed, and the tight spot between his shoulder blades eased.

A faint smile hovered at the edges of the Queen’s lips. Meeting her eyes for the briefest of instants, Deven thought, She knows exactly what our praise is worth. Elizabeth was no longer a young woman, whose head might be turned by pretty words; she recognised the ridiculous heights to which her courtiers’ compliments flew. Her pride enjoyed the flattery, and her political mind exploited it. By our words, we make her larger than life. And that serves her purposes very well.

This understanding did not make her any easier to face. “And family? Your father is a member of the Stationers’ Company, I believe.”

“And a gentleman, madam, with lands in Kent. He is an alderman of Farringdon Ward within, and has been pleased to serve the Crown in printing certain religious texts. For my own part, I do not follow in his trade; I am of Gray’s Inn.”

“Though your studies there are incomplete, as I understand. You went to the Netherlands, did you not?”

“Indeed, madam.” A touchy subject, given the failures there, and the Queen’s reluctance to send soldiers in the first place. Yet his military conduct in the Low Countries was part of what distinguished him enough to be here today. “I served with your gentleman William Russell at Zutphen two years ago.”

The Queen fiddled idly with a silk fan, eyes still fixed on him. “What languages have you?”

“Latin and French, madam.” What Dutch he had learned was not worth claiming.

She immediately switched to French. “Have you travelled to France?”

“I have not, madam.” He prayed his accent was adequate, and thanked God she had not chosen Latin. “My studies kept me occupied, and then the troubles made it quite impossible.”

“Good. Too many of our young men go there and come back Catholic.” This seemed to be a joke, as several of the courtiers chuckled dutifully. “What of poetry? Do you write any?”

At least Hunsdon had warned him of this, that she would ask questions having nothing to do with his ostensible purpose for being there. “She has standards,” the Lord Chamberlain had said, “for anyone she keeps around her. Beauty, and an appreciation for beauty; whatever your duties at court, you must also be an ornament to her glory.”

“I do not write my own, madam, but I have attempted some works of translation.”

Elizabeth nodded, as if it were a given. “Tell me, which poets have you read? Have you translated Virgil?”

Deven parried this and other questions, striving to keep up with the Queen’s agile mind as it leapt from topic to topic, and all in French. She might be old, but her wits showed no sign of slowing, and from time to time she would make a jest to the surrounding courtiers, in English or in Italian. He fancied they laughed louder at the Italian sallies, which he could not understand. Clearly, if he were accepted at court, he would need to learn it. For self-protection.

Elizabeth broke off the interrogation without warning and looked past Deven. “Lord Hunsdon,” she said, and the nobleman stepped forward to bow. “Tell me. Would my life be safe in this gentleman’s hands?”

“As safe as it rests with any of your Grace’s gentlemen,” the grey-haired baron replied.

“Very encouraging,” Elizabeth said dryly, “given that we executed Tylney for conspiracy not long ago.” She turned her forceful attention to Deven once more, who fought the urge to hold his breath and prayed he did not look like a pro-Catholic conspirator.

At last she nodded her head decisively. “He has your recommendation, Hunsdon? Then let it be so. Welcome to my Gentlemen Pensioners, Master Deven. Hunsdon will instruct you in your duties.” She held out one fine, long-fingered hand, the hands featured in many of her portraits, because she was so proud of them. Kissing one felt deeply strange, like kissing a statue, or one of the icons the papists revered. Deven backed away with as much speed as was polite.

“My humblest thanks, your Grace. I pray God my service never disappoint.”

She nodded absently, her attention already on the next courtier, and Deven straightened from his bow with an inward sigh of relief.

Hunsdon beckoned him away. “Well spoken,” the Lord Chamberlain and Captain of the Gentlemen Pensioners said, “though defence will be the least of your duties. Her Majesty never goes to war in person, of course, so you will not find military action unless you seek it out.”

“Or Spain mounts a more successful invasion,” Deven said. The baron’s face darkened. “Pray God it never come.”

The two of them made their way through the gathered courtiers in the presence chamber and out through magnificently carved doors into the watching chamber beyond. “The new quarter begins at Michaelmas,” Hunsdon said. “We shall swear you in then; that should give you time to set your affairs in order. A duty period lasts for a quarter, and the regulations require you to serve two each year. In practice, of course, many of our band have others stand in for them, so that some are at court near constantly, others hardly at all. But for your first year, I will require you to serve both assigned periods.”

“I understand, my lord.” Deven had every intention of spending the requisite time at court, and more if he could manage it. One did not gain advancement without gaining the favour of those who granted it, and one did not do that from a distance. Not without family connections, at any rate, and with his father so new to the gentry, he was sorely lacking in those.

As for the connections he did have… Deven had kept his eyes open, both in the presence chamber and this outer room, populated by less favoured courtiers, but nowhere had he seen the one man he truly hoped to find. The man to whom he owed his good fortune this day. Hunsdon had recommended him to the Queen, as was his privilege as captain, but the notion did not originate with him.

Unaware of Deven’s thoughts, Hunsdon went on talking. “Have better clothes made, before you begin. Borrow money if you must; no one will remark upon it. Hardly a man in this court is not in debt to one person or another. The Queen takes great delight in fashion, both for herself and those around her. She will not be pleased if you look plain.”

One visit to the elite realm of the presence chamber had convinced him of that. Deven was already in debt; preferment did not come cheaply, requiring gifts to smooth his path every step of the way. It seemed he would have to borrow more, though. This, his father had warned him, would be his lot: spending all he had and more in the hopes of having more in the future.

Not everyone won at that game. But Deven’s grandfather had been all but illiterate; his father, working as a printer, had earned enough wealth to join the ranks of the gentry; Deven himself intended to rise yet higher.

He even had a notion for how to do it—if he could only find the man he needed. Descending a staircase two steps behind Hunsdon, Deven said, “My lord, could you advise me on how to find the Principal Secretary?”

“Eh?” The baron shook his head. “Walsingham is not at court today.”

Damnation. Deven schooled himself to an outward semblance of pleasantry. “I see. In that case, I believe I should—”

His words cut off, for faces he recognised were waiting in the gallery below. William Russell was there, along with Thomas Vavasour and William Knollys, two others he knew from the fighting in the Low Countries. At Hunsdon’s confirming nod, they loosed glad cries and surged forward, clapping him on the back.

The suggestion he had been about to make, that he return to London that afternoon, was trampled before he could even speak it. Deven struggled with his conscience for a minute at most before giving in. He was a courtier now; he should enjoy the pleasures of a courtier’s life.

THE ONYX HALL, LONDON

17 September 1588

The polished stone walls reflected the quiet murmurs, the occasional burst of cold, sharp laughter, echoing up among the sheets of crystal and silver filigree that filled the space between the vaulting arches. Chill lights shone down on a sea of bodies, tall and short, twisted and fair. Court was not often so well attended, but something was expected to happen today. No one knew what—there were rumours; there were always rumours—but no one would be absent who could possibly attend.

And so the fae of London gathered in the Onyx Hall, circulating across the black-and-white pietre dura marble of the great presence chamber. One did not have to be a courtier to gain entry to this room; among the lords and gentlewomen were visitors from outlying areas, most of them dressed in the same ordinary clothing they wore every day. They formed a plain, sturdy backdrop against which the finery of the courtiers shone all the more vividly. Gowns of cobwebs and mist, doublets of rose petals like armour, jewels of moonlight and starlight and other intangible riches: the fae who called the Onyx Hall home had dressed for a grand court occasion.

They had dressed, and they had come; now they waited. The one empty space lay at the far end of the presence chamber, a high dais upon which a throne sat empty. Its intricate network of silver and gems might have been the web of a spider, waiting for its spinner to return. No one looked at it openly, but each fae present glanced at it from time to time out of the corners of their eyes.

Lune looked at it more often than most. The rest of the time she drifted through the hall, silent and alone. Whispers spread fast; even those from outside London seemed to have heard of her fall from favour. Or perhaps not; country fae often kept their distance from courtiers, out of fears ranging from the well-founded to the ludicrous. Whatever the cause, the hems of her sapphire skirts rarely brushed anyone else’s. She moved in an invisible sphere of her own disgrace.

From the far end of the hall, a voice boomed out like the crash of waves on rocky shores. “She comes! From the white cliffs of Dover to the stones of the ancient wall, she rules all the fae of England. Make way for the Queen of the Onyx Court!”

The sea of bodies rippled in a sudden ebb tide, every fae present sinking to the floor. The more modest—the more fearful—prostrated themselves on the black-and-white marble, faces averted, eyes tightly shut. Lune listened as heavy steps thudded past, measured and sure, and then behind them the ghostly whisper of skirts. A chill breeze wafted through the room, more imagined than felt.

A moment later, the doors to the presence chamber boomed shut. “By command of your mistress, rise, and attend to her court,” the voice again thundered, and with a shiver the courtiers returned to their feet and faced the throne.

Invidiana might have been a portrait of herself, so still did she sit. The crystal and jet embroidered onto her gown formed bold shapes that complemented those of the throne, with the canopy of estate providing a counterpoint above. Her high collar, edged with diamonds, framed a flawless face that showed no overt expression—but Lune fancied she could read a hint of secret amusement in the cold black eyes.

She hoped so. When Invidiana was not amused, she was often angry.

Lune avoided meeting the gaze of the creature that waited at Invidiana’s side. Dame Halgresta Nellt stood like a pillar of rock, boots widely planted, hands clasped behind her broad back. The weight of her gaze was palpable. No one knew where Invidiana had found Halgresta and her two brothers—somewhere in the North, though some said they had once been fae of the alfar lands across the sea, before facing exile for unknown crimes—but the three giants had fought a pitched combat before Invidiana’s throne for the right to command her personal guard, and Halgresta had won. Not through size or strength, but through viciousness. Lune knew all too well what the giant would like to do to her.

A sinuous fae clad in an emerald-green doublet that fit like a second skin ascended two steps up the dais and bowed to the Queen, then faced the chamber. “Good people,” Valentin Aspell said, his oily voice pitched to carry, “today, we play host to kinsmen who have suffered a tragic loss.”

At the Lord Herald’s words, the doors to the presence chamber swung open. Laying one hand on the sharp, fluted edge of a column, Lune turned, like everyone else, to look.

The fae who entered were a pathetic sight. Muddy and haggard, their simple clothes hanging in rags, they shuffled in with all the terror and awe of rural folk encountering for the first time the cold splendour of the Onyx Hall. The watching courtiers eddied back to let them pass, but there was none of the respect that had immediately opened a path for Invidiana; Lune saw more than a few looks of malicious pity. Behind the strangers walked Halgresta’s brother Sir Prigurd, who shepherded them along with patient determination, nudging them forward until they came to a halt at the foot of the dais. There was a pause. Then a sound rumbled through the hall: a low growl from Halgresta. The peasants jerked and threw themselves to the floor, trembling.

“You kneel before the Queen of the Onyx Court,” Aspell said, with only moderate inaccuracy; two of the strangers were indeed kneeling, instead of lying on the floor. “Tell her, and the gathered dignitaries of her realm, what has befallen you.”

One of the two kneeling fae, a stout hob who looked in danger of losing his cheerful girth, obeyed the order. He had the good sense not to rise.

“Nobble Queen,” he said, “we hev lost ev’ry thing.”

The account that followed was delivered in nearly impenetrable country dialect. Lune soon gave up on understanding every detail; the tenor was clear enough. The hob had served a certain family since time out of mind, but the mortals were recently thrown off their land, and their house burnt to the ground. Nor was he the only one to suffer such misfortune: a nearby marsh had been drained and the entire area, former house and all, given over to a new kind of farming, while a road being laid in to connect some insignificant town to some slightly less insignificant town had resulted in the death of an oak man and the levelling of a minor faerie mound.

When the last of the tale had spilled out, another pause ensued, and then the hob nudged a battered and sorry-looking puck still trembling on the floor at his side. The puck yelped, a sharp and nervous sound, and produced from somewhere a burlap sack.

“Nobble Queen,” the hob said again, “we hev browt yew sum gifts.”

Aspell stepped forward and accepted the sack. One by one, he lifted its contents free and presented them to Invidiana: a rose with ruby petals, a spindle that spun on its own, a cup carved from a giant acorn. Last of all was a small box, which he opened facing the Queen. A rustle shivered across the hall as half the courtiers craned to see, but the contents were hidden.

Whatever they were, they must have satisfied Invidiana. She waved Aspell off with one white hand and spoke for the first time.

“We have heard your tale of loss, and your gifts are pleasing to our eyes. New homes will be found for you, never fear.”

Her cool, unemotional words set off a flurry of bowing and scraping from the country fae; the hob, still on his knees, pressed his face to the floor again and again. Finally Prigurd got them to their feet, and they skittered out of the chamber, looking relieved at both their good fortune and their departure from the Queen’s presence.

Lune pitied them. The poor fools had no doubt given Invidiana every treasure they possessed, and much good would it do them. She could easily guess the means by which those rural improvements had begun; the only true question was what the fae of that area had done to so anger the Queen, that she retaliated with the destruction of their homes.

Or perhaps they were no more than a means to an end. Invidiana looked out over her courtiers, and spoke again. The faint hint of kindness an optimistic soul might have read into her tone before was gone. “When word reached us of this destruction, we sent our loyal vassal Ifarren Vidar to investigate.” From a conspicuous spot at the foot of the dais, the skeletally thin Vidar smirked. “He uncovered a shameful tale, one our grieving country cousins dreamed not of.”

The measured courtesy of her words was more chilling than rage would have been. Lune shivered, and pressed her back against the sharp edges of the pillar. Sun and Moon, she thought, let it not touch me. She had played no part in these unknown events, but that meant nothing; Invidiana and Vidar were well practiced in the art of fabricating guilt as needed. Had the Queen preserved her from Halgresta Nellt only to lay this trap for her instead?

If so, it was a deeper trap than Lune could perceive. The tale Invidiana laid out was undoubtedly false—some trumped-up story of one fae seeking revenge against another through the destruction of the other fellow’s homeland—but the person it implicated was no one Lune knew well, a minor knight called Sir Tormi Cadogant.

The accused fae did the only thing anyone could, in the circumstances. Had he not been at court, he might have run; it was treason to seek refuge among the fae of France or Scotland or Ireland, but it might also be safety, if he made it that far. But he was present, and so he shoved his way through the crowd and threw himself prostrate before the throne, hands outstretched in supplication.

“Forgive me, your Majesty,” he begged, his voice trembling with very real fear. “I should not have done so. I have trespassed against your royal rights; I confess it. But I did so only out of—”

“Silence,” Invidiana hissed, and his words cut off.

So perhaps Cadogant was the target of this affair. Or perhaps not. He was certainly not guilty, but that told Lune nothing.

“Come before me, and kneel,” the Queen said, and shaking like an aspen leaf, Cadogant ascended the stairs until he came before the throne.

One long-fingered white hand went to the bodice of Invidiana’s gown. The jewel that lay at the centre of her low neckline came away, leaving behind a stark patch of black in the intricate embroidery. Invidiana rose from her throne, and everyone knelt again, but this time they looked up; all of them, from Aspell and Vidar down to the lowliest brainless sprite, knew they were required to witness what came next. Lune watched from her station by the pillar, transfixed with her own fear.

The jewel was a masterwork even among the fae, a perfectly symmetrical tracery of silver drawn down from the moon itself, housing in its centre a true black diamond: not the painted gems humans wore, but a stone that held dark fire in its depths. Pearls formed from mermaid’s tears surrounded it, and razor-edged slivers of obsidian ringed the gem’s edges, but the diamond was the focal point, and the source of power.

Looming above the kneeling Cadogant, Invidiana was a pitiless figure. She reached out her hand and laid the jewel against the fae’s brow, between his eyes.

“Please,” Cadogant whispered. The word was audible to the farthest corners of the utterly silent hall. Brave as he was, to face the Queen’s wrath and hope for what passed for mercy in her, he still begged.

A quiet clicking was his answer, as six spidery claws extended from the jewel and laid needle-sharp tips against his skin.

“Tormi Cadogant,” Invidiana said, her voice cold with formality, “this ban I lay upon thee. Nevermore wilt thou bear title or honour within the borders of England. Nor wilt thou flee to foreign lands. Instead, thou wilt wander, never staying more than three nights in one place, neither speaking nor writing any word to another; thou wilt be as one mute, an exile within thine own land.”

Lune closed her eyes as she felt power flare outward from the jewel. She had seen it used before, and knew some of how it worked. There was only one consequence for breaking such a ban.

Death.

Not just an exile, but one forbidden to communicate. Cadogant must have been plotting some treason. And this was a message to his co-conspirators, subtle enough to be understood, without telling the ignorant that a conspiracy had ever existed in the first place.

Her skin shuddered all over. Such a fate might have been hers, had Invidiana been any more enraged by her failure.

“Go,” Invidiana snapped. Lune did not open her eyes until the hesitant, stumbling footsteps passed out of hearing.

When Cadogant was gone, Invidiana did not seat herself again. “This work is concluded for now,” she said, and her words bore the terrible implication that Cadogant might not be the last victim. But whatever would happen next, it would not happen now. Everyone cast their gaze down again as the Queen swept from the room, and when the doors shut at last behind her, everyone let out a collective breath.

In the wake of her departure, music began to thread a plaintive note through the air. Glancing back toward the dais, Lune saw a fair-haired young man lounging on the steps, a recorder balanced in his nimble fingers. Like all of Invidiana’s mortal pets, his name was taken from the stories of the ancient Greeks, and for good reason; Orpheus’s simple melody did more than simply evoke the loss and sorrow of the peasant fae, and Cadogant’s downfall. Some of those who had shown cruel amusement before now frowned, regret haunting their eyes. One dark-haired fae woman began to dance, her slender body flowing like water, giving form to the sound. Lune pressed her lips together and hurried to the door, before she, too, could be drawn into Orpheus’s snare.

Vidar was lounging against one doorpost, bony silk-clad arms crossed over his chest. “Did you enjoy the show?” he asked, that same smirk hovering again on his lips.

Lune longed for a response to that, some perfect, cutting reply to check his surety that he stood in the Queen’s favour and she did not. After all, fae had been known to suffer apparent disgrace, only for it later to be revealed as part of some scheme. But no such scheme sheltered her, and her wit failed. She felt Vidar’s smirk widen as she shouldered past him and out of the presence chamber.

His words had unsettled her more than she realised. Or perhaps it was Cadogant, or those poor, helpless country pawns. Lune could not bear to stay out in the public eye, where she imagined every whisper spoke of her downfall. Instead she made her way, with as much haste as she could afford, through the tunnels to her own quarters.

The closing of the door gave the illusion of sanctuary. These two rooms were richly decorated, with a softer touch than in the public areas of the Hall; thick mats of woven rushes covered her floor, and tapestries of the great fae myths adorned her walls. The marble fireplace flared into life at her arrival, casting a warmer glow over the interior, throwing long shadows from the chairs that stood before it. Empty chairs; she had not entertained many guests lately. A doorway on the far side led to her bedchamber.

At least she still had this, her sanctum. She had lost the Queen’s favour, but not so terribly that she had been forced from the Onyx Hall, to wander like those poor bastards in search of a new home. Not so terribly as Cadogant had.

The very thought made her shiver. Straightening, Lune crossed the room to a table that stood by her bedchamber door, and the crystalline coffer atop it.

She hesitated before opening it, knowing the dreary sight that would meet her eyes. Three morsels sat inside: three bites of coarse bread, who knew how old, but as fresh now as when some country housewife laid them out on the doorstep as a gift to the fae. Three bites to sustain her, if the worst should happen and she should be sent away from the Onyx Hall—sent out into the mortal world.

They would not protect her for long.

Lune closed the coffer and shut her eyes. It would not happen. She would find a way back into Invidiana’s favour. It might take years, but in the meantime, all she had to do was avoid angering the Queen again.

Or giving Halgresta any excuse to come after her.

Lune’s fingers trembled on the delicate surface of the coffer; whether from fear or fury, she could not have said. No, she could not simply wait for her chance. That was not how one survived the Onyx Court. She would have to seek out an opportunity, or better yet, create one.

But how to do that, with so few resources available to her? Three bites of bread would not help her much. And Invidiana would hardly grant more to someone out of favour.

The Queen was not, however, the only source of mortal food.

Again Lune hesitated. To do this, she would have to go out of the Onyx Hall—which meant using one of her remaining pieces. That, or send a message, which would be even more dangerous. No, she couldn’t risk that; she would have to go in person.

Praying the sisters would be as generous as she hoped, Lune took a piece of bread from the coffer and went out before she could change her mind.

RICHMOND AND LONDON

18 September 1588

So this, Deven thought blearily as he fumbled the lid back onto the close stool, is the life of a courtier.

His right shoulder was competing with his head for which ached worse. His new brothers in the Gentlemen Pensioners had taught him to play tennis the previous night, in the high-walled chamber built for that purpose out in the gardens. He’d flinched inwardly at having to pay for entry, but once inside, he took to it with perhaps more enthusiasm than was wise. Then there was drinking and card games, late into the night, until Deven had little memory of how he had arrived here, sharing Vavasour’s bed, with their servants stretched out on the floor.

An urgent need to relieve himself had woken him; in the bed, Vavasour slept on. Scrubbing at his eyes, Deven contemplated following his fellow’s example, but told himself with resignation that he might as well put the time to use. Otherwise he would sleep until noon and then get caught up once more in the social dance; then it would be too late to leave, so he would stay another night, and so on and so forth until he found himself crawling away from court one day, bleary-eyed and bankrupt.

Checking his purse, he corrected that last thought. Perhaps not bankrupt, judging by his apparent luck at cards the previous night. But such winnings would not finance this life. Hunsdon was right: he needed to borrow money.

Deven suppressed the desire to groan and shook Peter Colsey awake. His manservant was in little better shape than he, having found other servants with whom to entertain himself, but fortunately he was also taciturn of a morning. He rolled off the mattress and confined himself to dire looks at their boots, his master’s doublet, and anything else that had the effrontery to require work from him at such an early hour.

The palace wore a different face at this time of day. The previous morning, Deven had been too much focused on his own purpose to take note of it, but now he looked around, trying to wake himself up gently. Servants hurried through the corridors, wearing the Queen’s livery or that of various nobles. Outside, Deven heard chickens squawking as two voices argued over who should get how many. Hooves thudded in the courtyard, moving fast and stopping abruptly: a messenger, perhaps. He bet his winnings from the previous night that Hunsdon and the other men who dominated the privy council were up already, hard at work on the business of her Majesty’s government.

Colsey brought him food to break his fast, and departed again to have their horses saddled. Soon they were riding out in morning sunlight far too bright.

They did not talk for the first few miles. Only when they stopped to water their horses at a stream did Deven say, “Well, Colsey, we have until Michaelmas. Then I am due to return to court, and under orders to be better dressed when I do.”

Colsey grunted. “Best I learn how to brush up velvet, then.”

“Best you do.” Deven stroked the neck of his black stallion, calming the animal. It was a stupid beast for casual riding—the horse was trained for war—but a part of the fiction that the Gentlemen Pensioners were still a military force, rather than a force that happened to include some military men. Three horses and two servants; he’d had to acquire another man to assist Colsey. That still earned him more than a few glares.

By afternoon the houses they passed were growing closer together, clustering along the south bank of the Thames and stringing out along the road that led to the bridge. Deven stopped to refresh himself with ale in a Southwark tavern, then cocked his gaze at the sky. “Ludgate first, Colsey. We shall see how quickly I can get out, eh?”

Colsey had the sense not to make any predictions, at least not out loud.

Their pace slowed considerably as they crossed London Bridge, Deven’s stallion having to shoulder his way through the crowds that packed it. He kept a careful hand on the reins. Travellers like him wended their way one step at a time, mingling with those shopping in the establishments built along the bridge’s length; he didn’t put it past the warhorse to bite someone.

Nor did matters improve much on the other side. Resigned by now to the slower pace, his horse drifted westward along Thames Street, taking openings where he found them. Colsey spat less-than-muffled curses as his own cob struggled to keep up, until at last they arrived at their destination in the rebuilt precinct of Blackfriars: John Deven’s shop and house.

Whatever private estimate Colsey had made about the length of their visit, Deven suspected it was not short. His father was delighted to learn of his success, but of course it wasn’t enough simply to hear the result; he wanted to know every detail, from the clothing of the courtiers to the decorations in the presence chamber. He had visited court a few times, but not often, and had never entered such an august realm.

“Perhaps I’ll see it myself someday, eh?” he said, beaming with unsubtle optimism.

And then of course his mother Susanna had to hear, and his cousin Henry, whom Deven’s parents had taken in after the death of John’s younger brother. It worked out well for all involved; Henry had filled the place that might otherwise have been Michael’s, apprenticing to John under the aegis of the Stationers’ and freeing him to pursue more ambitious paths. The conversation went to business news, and then of course it was late enough that he had to stay for supper.

A small voice in the back of Deven’s mind reflected that it was just as well; if he ate here, it was no coin out of his own purse. Why he should dwell on pennies when he was in debt for pounds made no sense, but there it was.

After supper, when Susanna and Henry had been sent off, Deven sat with his father by the fire, a cup of fine malmsey dangling from his fingers. The light flickered beautifully through the Venetian glass and the red wine within, and he watched it, pleasantly relaxed.

“Your place is assured, my son,” John Deven said, stretching his feet toward the fire with a happy sigh.

Elizabeth’s ominous words about Tylney had stayed in Deven’s mind, but his father was right. There were greybeards in the Pensioners, some of them hardly fit for any kind of action. Unless he did something deeply foolish—like conspiring to kill the Queen—he might stay there until he wished to leave.

Some men did leave. Family concerns called them away, or a disenchantment with life at court; some broke their fortunes instead of making them. Seventy marks yearly, a Pensioner’s salary, was not much in that world, and not everyone succeeded at gaining the kinds of preferment that brought more.

But then his father drove all money concerns from his mind, with one simple phrase. “Now,” John Deven said, “to find you a wife.”

It startled a laugh from him. “I have scarcely earned my place, Father. Give me time to get my feet under me, at least.”

“’Tis not me you should be asking for time. You have just secured a favourable position, one close to her Majesty; there will be gentlewomen seeking after you like hawks. Perhaps even ladies.”

There certainly had been women watching the tennis matches the previous day. A twinge in Deven’s shoulder made him wonder how bad a fool he had made of himself. “No doubt. But I know better than to rush into anything, particularly when I am serving the Queen. They say she’s very jealous of those around her, and dislikes scandalous behaviour in her courtiers.” The last thing he needed was to end up in the Tower because he got some maid of honour pregnant.

The best eye to catch, of course, was that of the Queen herself. But though Deven was ambitious, and her affection was a quick path to reward, he was not at all certain he wanted to compete with the likes of the young Earl of Essex. That would rapidly bring him into situations he could not survive.

“Marriage is no scandal,” his father said. “Have a care for how you comport yourself, but do not stand too aloof. A match at court might be very beneficial indeed.”

His father seemed likely to keep pressing the matter. Deven dodged it with a distraction. “If all goes as planned, my time will be very thoroughly employed elsewhere.”

John Deven’s face settled into graver lines. “You have spoken to Walsingham, then?”

“No. He was not at court. But I will do so at the first opportunity.”

“Be wary of rushing into such things,” his father said. Much of the relaxed atmosphere had gone out of the air. “He serves an honourable cause, but not always by honourable means.”

Deven knew this very well; he had done some of that work in the Low Countries. Though not the most sordid parts of it, to be sure. “He is my most likely prospect for preferment, Father. But I’ll keep my wits about me, I promise.”

With that, his father had to be satisfied.

LONDON AND ISLINGTON

18 September 1588

Leaving the Onyx Hall was not so simple as Lune might have hoped. In the labyrinthine politics of court, someone would find a way to read her departure as suspicious, should she go out too soon after Invidiana’s sentencing of Cadogant. Vidar, if no one else.

So she wandered for a time through the reaches of the Onyx Hall, watching fae shy away from her company. It was an easy way to fill time; though the subterranean faerie palace was not so large as the city above, it was far larger than any surface building, with passages playing the role of streets, and complexes of chambers given over to different purposes.

In one open-columned hall she found Orpheus again, this time playing dance music; fae clapped as one of their number whirled around with a partner in a frenzied display. Lune placed herself along the wall and watched as a grinning lubberkin dragged a poor, stumbling human girl on, faster and faster. The mortal looked healthy enough, though exhausted; she was probably some maidservant lured down into the Onyx Hall for brief entertainment, and would be returned to the surface in the end, disoriented and drained. Those who had been there for a long time, like Orpheus, acquired a fey look this girl did not yet have.

Their attention was on the dance. Unobserved, Lune slipped across to the other side of the hall and out through another door.

She took a circuitous route, misleading to anyone who might see her passing by, but also necessary; one could not simply go straight to one’s destination. The Onyx Hall connected to the world above in a variety of places, but those places did not match up; two entrances might lie half the city apart on the surface, but side-by-side down below. It was one of the reasons visitors feared the place. Once inside, they might never find their way out again.

But Lune knew her path. Soon enough she entered a small, deserted chamber, where the stone walls of the palace gave way to a descending lacework of roots.

Standing beneath their canopy, she took a deep breath and concentrated.

The rippling, night-sky sapphire of her gown steadied and became plainer blue broadcloth. The gems that decorated it vanished, and the neckline closed up, ending in a modest ruff, with a cap to cover her hair. More difficult was Lune’s own body; she had to focus carefully, weathering her skin, turning her hair from silver to a dull blond, and her shining eyes to a cheerful blue. Fae who were good at this knew attention to detail was what mattered. Leave nothing unchanged, and add those few touches—a mole here, smallpox scars there—that would speak convincingly of ordinary humanity.

But building the illusion was not enough, on its own. Lune reached into the purse that hung from her girdle and brought forth the bread from her coffer.

The coarsely ground barley caught in her teeth; she was careful to swallow it all. As food, she disdained it, but it served its own purpose, and for that it was more precious than gold. When the last bit had been consumed, she reached up and stroked the nearest root.

With a quiet rustle, the tendrils closed around and lifted her up.

She emerged from the trunk of an alder tree that stood along St. Martin’s Lane, no more than a stone’s throw from the structures that had grown like burls from the great arch and surrounding walls of Aldersgate. The time, she was surprised to discover, was early morning. The Onyx Hall did not stand outside human time the way more distant realms did—that would make Invidiana’s favourite games too difficult—but it was easy to lose track of the hour.

Straightening her cap, Lune stepped away from the tree. No one had noticed her coming out of the trunk. It was the final boundary of the Onyx Hall, the last edge of the enchantments that protected the subterranean palace lying unseen below mortal feet; just as the place itself remained undiscovered, so would people not be seen coming and going. But once away from its entrances, the protections ended.

As if to hammer the point home, the bells of St. Paul’s Cathedral rang out the hour from within the tightly packed mass of London. Lune could not repress the tiniest flinch, even as she felt the sound wash over her harmlessly. She had done this countless times before, yet the first test of her own protections always made her nervous.

But she was safe. Fortified by mortal food against the power of mortal faith, she could walk among them, and never fear her true face would be revealed.

Settling into her illusion, Lune set out, walking briskly through the gate and out of London.

The morning was bright, with a crisp breeze that kept her cool as she walked. The houses crowding the lane soon spaced themselves more generously, but there was traffic aplenty, an endless flow of food, travellers, and goods into and out of the city. London was a voracious thing, chewing up more than it spat back out, and in recent years it had begun to swallow the countryside. Lune marvelled at the thronging masses who flooded the city until it overflowed, spilling out of its ancient walls and taking root in the formerly green fields that lay without. They lived like ants, building up great hills in which they lived by the hundreds and thousands, and then dying in the blink of an eye.

A mile or so farther out, it was a different matter. The clamour of London faded behind her; ahead, beyond the shooting fields, lay the neighbouring village of Islington, with its manor houses and ancient, shading trees. And along the Great North Road, the friendly, welcoming structure of the Angel Inn.

The place was moderately busy, with travellers and servants alike crossing the courtyard that lay between the inn and the stables, but that made Lune’s goal easier; with so many people about, no one took particular notice of one more. She passed by the front entrance and went toward the back, where the hillside was dominated by an enormous rosebush, a tangled, brambly mass even the bravest soul would be afraid to trim back.

This, too, had its own protections. No one was there to watch as Lune cupped a late-blooming rose in her hand and spoke her name into the petals.

Like the roots of the alder tree in London, the thorny branches rustled and moved, forming a braided archway starred with yellow blossoms. Inside the archway were steps, leading down through the earth, their wood worn smooth by countless passing feet. Charmed lights cast a warm glow over the interior. Lune began her descent, and the rosebush closed behind her.

The announcement of her name did not open the bush; it only told the inhabitants someone had come. But visitors were rarely kept waiting, outside or in. By the time Lune reached the bottom of the steps, someone was there.

“Welcome to the Angel, my lady,” Gertrude Goodemeade said, a sunny smile on her round-cheeked face as she bobbed a curtsy. “’Tis always a pleasure to see you here. Come in, please, please!”

No doubt the Goodemeade sisters gave the same friendly greeting to anyone who crossed their threshold—just as, no doubt, more courtiers came here than would admit it—and yet Lune did not doubt the words were sincere. It was in the sisters’ nature. They came from the North originally—brownies were Border hobs, and Gertrude’s voice retained traces of the accent—but they had served the Angel Inn since its construction, and supposedly another inn before that, and on back past what anyone could remember. Many hobs were insular folk, attached to a particular mortal family and unconcerned with anyone else, but these two understood giving hospitality to strangers.