9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Colla & Gen Verlag

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

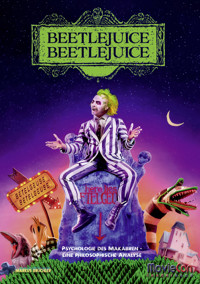

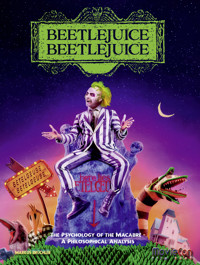

Beetlejuice: The Psychology of the Macabre – A Philosophical Analysis Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice is a film that playfully blurs the line between life and death, uncovering profound truths about human existence along the way. This in-depth analysis not only celebrates the franchise as a cult classic but also unravels it as a philosophical and psychological masterpiece that uses dark humor to tackle life’s big questions. How can we explain the grotesque charm of a ghost who breaks the rules yet longs for meaning? What do the bizarre, Kafkaesque visuals reveal about our own fears of mortality? And why are we drawn to characters who exist on society’s fringes? This book seeks answers—and the essence of what makes Beetlejuice timeless. Through a detailed exploration, the book demonstrates how Burton’s eccentric aesthetics and darkly humorous storytelling demystify death while preserving its existential weight. The fusion of philosophical depth and grotesque wit makes Beetlejuice a work that both entertains and unsettles—its strength lying precisely in this duality. For those who refuse to settle for the surface and are willing to look beyond the garish set designs, Beetlejuice: The Psychology of the Macabre – A Philosophical Analysis opens doors to a world as strange as it is familiar—perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of our times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Introduction to the world of “Beetlejuice”6

Beetlejuice (Movie, 1988)9

The story of “Beetlejuice” from an analytical point of view12

Thematic Analyses in „Beetlejuice“48

The Reconstruction of Family Dynamics48

The Conflict Over Home: Protective Instinct, Ownership, and Identity51

The Supernatural as a Reflection of Human Nature54

The Commercialization of the Supernatural: Business and Greed57

Death as a Gateway: Exploring Mortality and the Afterlife60

The Immortal Bond: Marriage in the World of "Beetlejuice"64

City vs. Country: The Clash of Lifestyles66

Motifs, Symbols and Allegories in “Beetlejuice”69

The Subversion of Perception: Spiders, Models, and Disturbing Imagery69

Delia Deetz: Pretension, Aesthetics, and the Coldness of the Modern Self71

The making of “Beetlejuice”75

Creative Vision and Adaptation75

Altered Visions and Script Revisions77

The Casting of "Beetlejuice": A Journey Through Unconventional Choices79

A Cinematic Collaboration and the Visionary Approach to Production Design80

From Scouting Locations to Practical Effects83

Production Design and the Charm of Imperfection86

The Depiction of the Afterlife88

Hidden Gems and Filmmaking Choices90

The soundtrack to “Beetlejuice”93

The Unconventional Melodies of "Beetlejuice"93

The Chaos and Brilliance of Danny Elfman’s "Beetlejuice" Score95

The Soundscape of "Beetlejuice": Danny Elfman’s Musical Storytelling Experiment97

The Musical Brilliance: Elfman’s Defining Moments99

The Inconsistent Development of the "Beetlejuice" Score: Examining the 2011 Reissue101

The Role of "Day-O" in "Beetlejuice": A Cultural and Cinematic Perspective103

The Power of Rhythm: "Jump in the Line" in the Unforgettable Finale of "Beetlejuice"105

The Calypso Undercurrents in "Beetlejuice": An Analysis of "Man Smart (Woman Smarter)" and "Sweetheart from Venezuela"108

Release and critical response on “Beetlejuice”111

Cult Classic Status and Lasting Appeal for “Luxury Consumers”111

A Polarizing and Eccentric Masterpiece of Film History112

The characters in “Beetlejuice”116

Adam Maitland116

Quiet Resilience and Emotional Growth116

Alec Baldwin118

Barbara Maitland122

The Psychological Dimensions of Barbara Maitland122

Geena Davis124

Beetlejuice / Betelgeuse127

The Macabre Charisma and Complex Morality of Beetlejuice127

The Creation of Beetlejuice: A Character Born from Improvisation and Dark Comedy131

Michael Keaton134

Lydia Deetz138

A Study of Identity, Alienation, and Growth138

Lydia Deetz: The Evolution of a Character During Production140

Winona Ryder142

Delia Deetz146

The Balancing Act Between Creativity and Control146

Catherine O’Hara148

Charles Deetz150

A Study of Complex Motivations and Subtle Vulnerabilities150

Jeffrey Jones152

Otho Fenlock154

The Illusion of Status154

Glenn Shadix156

The Dog158

Jane Butterfield (Annie McEnroe)160

Maxie Dean (Robert Goulet) and Sarah Dean (Maree Cheatham)162

Beryl (Adelle Lutz)164

Bernard (Dick Cavett)166

Grace (Susan Kellermann)168

The Afterlife170

The characters in the afterlife in “Beetlejuice”173

The Grey Doorway Ghosts173

The Camper176

The Diver178

Ferndock180

Miss Argentina182

The magician's assistant185

The Preacher187

Harry the hunter190

The Smoker193

The Green Man196

Open Heart Patient199

Road Kill Man202

The Skeleton Crew205

Hanging Man208

The Janitor211

The Lost Souls214

Juno217

Dante’s Inferno Girls220

The Football Players223

The Ghosts in the Waiting Area226

Minister: Judge Skullface229

The Shaman232

Locations in “Beetlejuice”235

The Maitland Residence235

Maitland Hardware238

Key Places in Winter River240

The Winter River model242

The Saturn245

The Neitherworld and the Beyond248

The Sandworms252

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (Movie, 2024)255

The story of “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice” from an analytical perspective257

Between the Living and the Dead: Lydia Deetz as a Mediator Between Worlds257

Fractured Bonds: Lydia Deetz’s Relationships with Delia and Astrid259

Chaos and Control: The Dynamics of the In-Between World263

A Macabre Romance: Beetlejuice and the Mystery of Delores265

Love in the Face of Loss: Rory’s Proposal and Family Discord267

Crossing Paths: Astrid Meets Jeremy269

Confronting the Past: Halloween, Family Heirlooms, and Beetlejuice271

A Descent into the Miniature Abyss: Lydia and Rory Confront Beetlejuice272

Crossing the Boundary: Astrid and Jeremy Enter the Afterlife276

Deadly Rituals: Delia’s Ceremony of Grief278

A Deal with the Demon: Lydia’s Pact with Beetlejuice280

Surreal Boundaries: Lydia and Beetlejuice’s Odyssey Through the Afterlife281

A Tangled Web in the Afterlife: Delia and Beetlejuice’s Alliance283

Chaos at the Altar: Lydia, Beetlejuice, and a Wedding for Eternity285

After the Chaos: Reflections and Farewells287

The making of “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice”289

A Look Back at the Afterlife: The Long and Winding Road to "Beetlejuice Beetlejuice"289

The Revival of a Ghostly Legacy290

Rediscovering Life After Death292

The Evolution of the Afterlife293

The Filming of "Beetlejuice Beetlejuice": A Journey Through Locations and Challenges295

The Deetz Residence Reimagined: Craftsmanship and Authenticity297

Reimagining the Afterlife: The Set Design298

Costume Design: Evolving the Wardrobe299

A World of Nostalgia and Innovation: The Production Design301

Refining the Raw Charm303

Between Tradition and Innovation: The Post-Production305

The Film Music in “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice”307

Harmonious Hauntings: The Music of "Beetlejuice Beetlejuice"307

A Challenging Comeback308

Reviving Ghostly Melodies310

Ethereal Echoes: The Expansive Musical Soundscape311

Sounds of alienation and hope: Tess Parks' “Somedays”313

Rain, Ritual, and Reflection: “MacArthur Park”315

Compounded Chaos: “Tragedy” and Dolores’ Revenge317

Echoes from the Past: “Day-O” and the Morbid Legacy319

The Sound of Rebellion: “Where’s the Man”321

A Quirky Serenade: “Right Here Waiting” and Beetlejuice’s Absurd Devotion323

Floating Between Worlds: Sigur Rós’ “Svefn-G-Englar”324

Ethereal Horror: Pino Donaggio’s “Carrie - Main Title”326

The release and critical response to “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice”329

The Characters in “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice”333

Astrid Deetz333

Grief and Redemption: A Psychological Analysis of Astrid Deetz333

A Deep Dive into Astrid Deetz Through Jenna Ortega’s Perspective335

Jenna Ortega337

Rory339

The Contradictory Television Star and Fiancé of Lydia Deetz339

Justin Theroux340

The Characters in the Afterlife342

Delores342

Monica Bellucci345

Jeremy Frazier347

Arthur Conti349

Wolf Jackson351

Willem Dafoe353

Richard355

Santiago Cabrera357

The Shrinkers359

The Janitor (Danny DeVito)362

Janet365

Dead Characters at the Immigration Office368

Dead Characters in the Waiting Room371

Beetlejuice: The Animated Series374

The Story: A Dual Reality of Adventure374

The Characters: An Ensemble of Eccentrics375

The Production: A Collaborative Endeavor376

Cultural Impact and Merchandising376

Adaptation and Evolution: Departures from the Film377

Legacy and Reception377

Tim Burton379

The Writer387

Imprint388

Beetlejuice: The Psychology of the Macabre

Markus Brüchler

Beetlejuice: The Psychology of the Macabre

A Philosophical Analysis

von

Markus Brüchler

Colla & Gen Verlag, Holzwickede

1. Edition, 2025

© 2025 All rights reserved.

Hauptstr. 65

59439 Holzwickede

Colla & Gen Verlag, Holzwickede

Introduction to the world of “Beetlejuice”

Beetlejuice Unleashed: The Eerie Charm of Two Films and an Animated Legacy

The Beetlejuice franchise stands as a vivid representation of late 20th-century cultural explorations into the supernatural, blending dark fantasy, macabre humor, and social commentary. The original 1988 film Beetlejuice, directed by Tim Burton, marked a pivotal moment in the genre of horror-comedy, transporting audiences to a realm where the dead were as lively as, if not more so than, the living. The franchise‘s backbone rests on the peculiar and chaotic spirit Betelgeuse, whose name—borrowed from a red supergiant star in the Orion constellation—infuses the narrative with cosmic mystique, straddling the line between playful eeriness and the profound infinity of the universe. Interestingly, its etymology links to Greek mythology and ancient stargazing, intertwining myths with the subversive pop culture that defined the 1980s.

Betelgeuse is an elusive character, shifting between ghost, demon, and supernatural trickster depending on the medium. He transcends conventional villainy, often emerging as an antihero who oscillates between malice and charisma. His motivations span from sowing chaos to a deep yearning for connection. Central to all iterations of Betelgeuse is his enigmatic relationship with Lydia Deetz—a young goth girl embodying curiosity for the strange and unusual. Their bond serves as a focal point in the films and animated series, veering between conflict-laden encounters, heartfelt camaraderie, and necessity-driven partnerships. This dynamic mirrors the ambivalence people often feel toward their own fears or darker fascinations. Lydia, in many ways, is the bridge between society‘s notions of „normalcy“ and the eccentricities that make life thrilling and unpredictable.

Following the initial success of the 1988 film, driven by Burton‘s unconventional storytelling and Danny Elfman‘s iconic score, the franchise expanded into various cultural formats, reflecting its lasting impact. The animated series, which aired from 1989 to 1991, deviated from the film‘s strictly ghostly mischief to explore broader themes, delving into the interplay between the „Mortal World“ and the „Neitherworld.“ Accessible to younger audiences, this interdimensional narrative retained the franchise‘s eccentricity while toning down its darker elements. The series expanded the world only hinted at in the film, offering a richer exploration of Betelgeuse‘s existence beyond mere ghostly pranks. Lydia was solidified as his co-conspirator and moral compass, further enriching their already complex dynamic.

The sequel Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (2024), released in September 2024, opened a new chapter for the film series, striking a balance between nostalgia and fresh explorations of themes like mortality, the unknown, and humanity‘s enduring fascination with defying both. Shaped by contemporary sensibilities, the sequel aims to resonate with audiences familiar with the franchise while inviting new viewers into its delightfully chaotic world. As society continues grappling with existential mysteries and the intersection of life and death, Beetlejuice remains relevant—a reflection on life‘s absurdities, identity, and the boundary between the living and the spectral.

This book delves deeply into the narrative nuances and thematic complexities of the Beetlejuice franchise, thoroughly covering both films and the animated series. It examines how humor is wielded to normalize the macabre and confront universal fears, while dissecting the psychological and philosophical dimensions underpinning these entertaining tales. The concept of the afterlife—a realm simultaneously frightening and humorously imperfect—is explored alongside the enduring questions of human existence these stories raise. Through this investigation, we explore how Beetlejuice expresses societal attitudes toward death and chaos, as well as what it means to belong—both in this world and the next. The juxtaposition of dark humor and existential musings provides a captivating lens through which to understand not only the film series itself but also broader cultural phenomena reflecting how the living perceive life after death.

The journey through the worlds Burton and his film crew conjured is brimming with quirky spirits, biting humor, and timeless themes that resonate across generations. This exploration of Beetlejuice is much more than an analysis of cinematic milestones; it is an investigation into how one mischievous spirit managed to become a cultural icon—one whose laughter echoes not just in the Neitherworld but also within our collective imagination.

Beetlejuice (Movie, 1988)

The Rebellious Spirit of “Beetlejuice”: A Critical Introduction

Tim Burton’s 1988 film Beetlejuice stands as a groundbreaking contribution to American cinema, carving out a unique space where dark fantasy, comedy, and horror intersect. Conceived by screenwriters Michael McDowell and Warren Skaaren and based on a story by McDowell and Larry Wilson, Beetlejuice serves as a prime example of Burton’s signature storytelling and visual style—a fusion of gothic whimsy and subversive humor that has become his hallmark. The film’s narrative, centered on a recently deceased couple grappling with the bureaucratic absurdities of the afterlife, unfolds against the quirky backdrop of their attempt to reclaim their former home. To do so, they enlist the help of Betelgeuse, a bio-exorcist with dubious methods and morals. In many ways, the story encapsulates a quintessentially American fascination with hauntings—both in terms of supernatural phenomena and the less tangible specter of societal change.

Adam and Barbara Maitland, played by Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis, offer an unusually grounded portrayal of ghosts. They are neither particularly frightening nor melodramatic; instead, they are endearingly naïve and deeply attached to the comforts of their small-town existence. This inversion of typical ghostly traits infuses humor into the otherwise eerie premise. Far from malevolent, they struggle with the newfound constraints of their existence, confined to their own home and powerless against the encroachment of modernity, represented by the Deetz family. It is within this context that Betelgeuse, portrayed with gleeful malevolence by Michael Keaton, makes his entrance. Betelgeuse is an anarchic force of nature, blurring the boundaries between the living and the dead. His crude humor and bizarre antics serve as both a comedic highlight and a disquieting reminder of the perils of meddling with the unknown.

The film’s uniqueness is not confined to its narrative but extends to its music. The soundtrack prominently features songs by Harry Belafonte, particularly from his albums Calypso and Jump Up Calypso. The inclusion of Belafonte’s music—especially the iconic "Banana Boat Song (Day-O)"—acts as a cultural bridge, contrasting the vibrancy of Caribbean rhythms with the otherwise somber tone of a ghost story. This juxtaposition underscores Burton’s ability to blend seemingly incompatible elements into an unforgettable and captivating experience. These musical choices contribute to the film’s distinctive tonal shifts, oscillating between lightheartedness and the macabre, highlighting the absurdity that permeates the story.

Upon its release, Beetlejuice garnered acclaim from both audiences and critics. Its commercial success—earning approximately $84 million against a modest $15 million budget—underscored the appeal of its unconventional storytelling and visual design. The film was celebrated for its contribution to genre cinema, earning an Academy Award for Best Makeup and several Saturn Awards, including Best Horror Film and Best Supporting Actress for Sylvia Sidney, who portrayed the beleaguered caseworker Juno. These accolades recognize not only Burton’s creativity but also the effectiveness of the film’s visual and performance elements, which have since become iconic.

The legacy of Beetlejuice is evident in the cultural expansion it inspired. The film’s success led to the creation of an animated series, several video games, and even a 2018 stage musical adaptation. This proliferation across various media underscores that the film is more than a cult classic—it has become a cultural phenomenon. Its exploration of life, death, and the bizarre interplay between the two has resonated with diverse audiences.

In this discussion, we will delve into the narrative structure, thematic foundations, and cultural resonance of Beetlejuice, examining how its humor, style, and portrayal of the afterlife contribute to its enduring popularity. Beneath the laughter and ghostly antics lies a complex meditation on change, identity, and the unspeakable boundaries that separate the living from the dead.

The story of “Beetlejuice” from an analytical point of view

Domestic Bliss and the Specter of Change: An Analysis of the Opening Scene

The opening scene of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice is deceptively understated yet rich with layers of thematic significance, setting the tone for the film’s exploration of domestic life and the disruptions that follow. As the camera pans over a serene forest and a quintessentially American small town, the audience is presented with an idyllic image of normalcy—a tranquil town filled with white farmhouses and tree-lined streets that evoke a sense of peace and order. However, the soundtrack tells a different story. The eerie yet captivating music hints at an underlying strangeness, suggesting that this seemingly ordinary setting is anything but. The sequence culminates in a focus on a large, somewhat dilapidated house perched on a hill—a visual metaphor for isolation, foreshadowing the separation between its occupants and the world around them.

The use of a scale model of the town in this scene is no coincidence but rather a significant symbol reflecting humanity’s desire to control and comprehend its environment. Adam Maitland, a bespectacled man, meticulously builds a miniature version of the town, hinting at his longing for order, familiarity, and dominion over his surroundings. The diminutive scale of the model, juxtaposed against the vastness of life itself, subtly underscores the futility of humanity’s attempts to impose meaning and structure on an uncertain world. Philosophically, this raises existential questions about the limits of human agency—how much control do we truly have over the forces that shape our lives? The subsequent appearance of a spider crawling ominously over the model’s roof symbolizes nature’s unpredictability and the fragility of human constructs. Adam’s casual act of releasing the spider unharmed reflects an attempt to dismiss discomfort and danger—a theme that will come back to haunt him and his wife.

Adam and Barbara Maitland embody the ideal of rural domesticity—content to spend their vacation at home, exchanging gifts tied to do-it-yourself projects. Their relationship is characterized by warmth, humor, and a shared belief in their home as a personal sanctuary. This portrayal taps into the cultural trope of the "American Dream," where stability, property ownership, and privacy reign supreme. The intimacy of their interactions—the playful kisses and lighthearted attempts to ignore the telephone—suggests a couple deeply in sync with one another and their shared domestic space. Yet this seemingly perfect harmony is almost immediately disrupted by external forces. The arrival of Jane, the local realtor, signals the intrusion of the outside world into their carefully maintained bubble of comfort. Jane’s insistence that the house should belong to a family with children introduces societal expectations that weigh heavily on the Maitlands, challenging the legitimacy of their happiness without offspring.

Jane’s presence injects a clear societal dimension into the narrative, critiquing the pressure to conform to traditional norms. The idea that a house must serve a specific purpose—housing a nuclear family—clashes with the Maitlands’ vision of their home as a personal refuge. The realtor’s condescending suggestion that the house is “too big” for a couple without children highlights societal biases that equate fulfillment with parenthood and expansion. Barbara’s visible frustration as she ushers Jane out underscores her resistance to such norms and her desire to preserve the sanctity of her own lifestyle choices. This raises questions about autonomy versus conformity—how much of what we pursue is truly our own, and how much is influenced by the expectations of others?

On a psychological level, the scene hints at the Maitlands’ inability to fend off external threats. Despite their efforts to keep Jane—and what she represents—out of their domain, they will soon learn that maintaining control over their environment is far more challenging, both in life and beyond. The interplay between the Maitlands and Jane also reflects a broader tension between private and public spheres. The coziness of their home is immediately juxtaposed with the unwelcome intrusion of an outsider, rendering the house itself a contested space. This subtle tension mirrors widespread cultural anxieties about privacy and the right to self-determination within one’s own home—a theme that remains relevant in an era increasingly defined by eroding personal boundaries.

From Life to Limbo: Tracing the Maitlands' Journey

When Adam and Barbara Maitland decide to take a trip into town, Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice begins its subtle yet impactful unraveling of their idyllic lives. Initially, the couple’s carefree attempt to maintain a normal life—their “staycation” focused on home improvement projects—serves as an idealized portrayal of rural domestic bliss. The film takes its time emphasizing their interactions with neighbors, the small-town atmosphere, and the simplicity of their desires. The bond between Adam and Barbara, marked by warmth and shared dreams, thrives within the cozy walls of their home. However, their drive into town and the ensuing car accident mark the first irreversible rupture between this comfort and an entirely different existence, hinting at the deeper themes of transience and the illusory nature of security.

The sequence is framed by meaningful interactions with their community, illustrating a stark contrast between the Maitlands’ vibrant, sociable life and the isolation they will face after the accident. Their banter with Jane and their exchange with Ernie—small-town social niceties embedded in their daily routine—serve as rituals defining their identity. These moments highlight their integration within their environment, their connections with others, and their sense of belonging. This sense of community is abruptly shattered by the car accident. Their plunge from the covered bridge becomes a literal descent into uncertainty—a journey from the familiar to the unknown, mirroring classical depictions of the transition from life to death in mythology and folklore. The crossing of the bridge holds symbolic weight; in literature and film, bridges often represent thresholds between worlds. In Beetlejuice, the covered bridge transforms into a gateway from the world of the living to the supernatural unknown.

The accident itself is depicted with striking brevity, yet its impact resonates profoundly. The small dog, teetering precariously on a wooden plank, introduces a touch of dark humor—an absurd juxtaposition of an innocent creature inadvertently triggering a catastrophic event. This moment epitomizes Burton’s use of humor to downplay the tragedy of death, turning a potential moment of horror into something almost slapstick. It subverts the expectation of fear, instead introducing a sense of surreal inevitability. Psychologically, the scene suggests that no matter how prepared or secure we may feel, chaos and unpredictability remain inherent aspects of existence. The fragility of life is underscored by the triviality of what ultimately disrupts it—a theme woven throughout the film as the characters grapple with their lack of control over the circumstances of their existence.

When Adam and Barbara return home, the audience experiences their unsettling transformation alongside them. Their confusion—marked by the sudden appearance of a blazing fire, a mysteriously altered sky, and Barbara’s inexplicably singed fingers—reflects an eerie awareness of the transition they have undergone. These moments are steeped in existential symbolism. The cuckoo clock, the unexplained fire, and the deep red sky all serve as visual metaphors for the Maitlands’ new state of being, evoking traditional gothic motifs of time, transformation, and the uncanny. The strange behavior of familiar objects—a fireplace igniting on its own, a clock suddenly chiming—signals that the Maitlands have entered a reality governed by entirely different rules. Their seemingly mundane world has been distorted, illustrating that death is not merely an end but a warped, altered reflection of life.

Adam’s determined step outside to retrace their path is particularly telling. It symbolizes his—and by extension humanity’s—instinct to rationalize the irrational and seek understanding amid chaos. The abrupt shift to a desolate, barren landscape underscores the futility of this quest. It serves as a symbolic depiction of the liminal state the Maitlands have entered—a haunting, otherworldly representation of the divide between the living world they knew and the undefined condition in which they now exist. The alien nature of the landscape accentuates their isolation, cut off from both their home and the comforts of the life they once knew.

The Maitlands’ journey following the accident raises significant questions about identity, place, and the human tendency to search for meaning. Philosophically, their confused attempts to continue familiar routines—lighting fires, brewing coffee, fetching wood—highlight the inherent conflict of maintaining a sense of self and normalcy in the face of profound change. They cling to familiar activities as a way to ground themselves, despite the obvious reality that the world they now inhabit is entirely different. This aspect of the film can be interpreted as a broader commentary on human behavior in response to the inevitability of death. Faced with uncertainty, the instinct is to hold onto the tangible elements of life, even when these rituals no longer serve their original purpose.

Between Worlds: The Maitlands' Journey Through the Afterlife

Adam and Barbara Maitland’s transition from the world of the living to the afterlife is a blend of confusion, irony, and reluctant adaptation—a mixture that Tim Burton captures with his signature visual whimsy. This segment of Beetlejuice provides deeper insight into the Maitlands’ bewilderment as they grapple with the surreal circumstances of their new existence. It becomes evident that the couple, stumbling through an unfamiliar set of rules governing life in their new reality, struggles with questions of identity and belonging in an environment that feels both familiar and completely transformed.

One of the most striking moments is Adam’s first venture outside. The brief appearance of a predatory creature—later identified as a “sandworm”—underscores the sheer unpredictability of the afterlife in which they are now trapped. The creature’s depiction starkly contrasts with the comforting imagery of their picturesque rural home, suggesting that the order and safety they once enjoyed have been replaced by chaos and danger. Barbara’s revelation that Adam, despite perceiving his absence as a mere moment, has been gone for hours further illustrates their disconnection from the temporal and spatial logic of the living world. This moment highlights the arbitrariness of time in their new state, evoking philosophical themes of time’s relativity and the disorientation that comes with the collapse of once-reliable concepts.

The Maitlands’ confrontation with the disappearance of their own reflections in mirrors marks another revelatory moment. In folklore, mirrors have often been seen as portals to other dimensions, reflections of the soul, or symbols of existential presence. The absence of their reflections signifies their separation from the physical world, indicating that they are now beings without substance, effectively severed from the realm of the living. Barbara’s attempts to understand their new state through tangible objects—a horse figurine, a mysterious handbook—reflect the human instinct to seek concrete explanations for abstract and unfathomable situations. This also poignantly illustrates her efforts to grasp the rules of their new existence and find solace in the familiar when faced with the inexplicable.

Philosophically, this section reveals much about the Maitlands’ desperate clinging to routines. Adam’s construction of a diorama featuring their own graves within his model town is steeped in dark humor and profound symbolism—a physical manifestation of their inability to detach from the materiality of their former lives. Despite their attempts to maintain a semblance of normalcy, the reality of their state is inescapable, a fact Barbara laments when she points out the absence of other deceased individuals, leaving them in an eerily isolated existence. Her wistful hope to encounter others underscores an enduring desire for community, even in the afterlife—a fundamental human need that transcends the boundaries of life and death. Adam’s attempt to comfort her—suggesting that “maybe this is heaven”—comes across as bittersweet, indicative of an optimism that is ultimately misplaced.

Another captivating aspect of this sequence is the juxtaposition of the Maitlands’ mundane, housebound activities with Betelgeuse’s grim lair—a chaotic, candlelit space suggesting a starkly different kind of afterlife. Betelgeuse’s interest in the Maitlands, conveyed through his derisive mockery of them as a “cute couple,” introduces a dark, anarchic element, viewing the Maitlands not as allies in the afterlife but as targets for manipulation. Betelgeuse’s interpretation of an obituary as a business opportunity serves as a cynical counterpoint to Adam and Barbara’s more innocent attempts to understand and adapt to their situation. His callousness and deliberate mispronunciation of his own name hint at a character who thrives on exploiting the vulnerabilities of others, amplifying the tension between his malevolence and the Maitlands’ inherently good-natured approach to their new state.

The arrival of Delia and Charles Deetz—announced by Barbara’s levitation and abrupt crash to the floor—ushers in the Maitlands’ next challenge. Delia’s initial disdain for the house, paired with Charles’s attempts to placate her, represents a dynamic starkly different from that of the Maitlands. While Adam and Barbara cherish the house as a personal sanctuary, Delia and Charles view it as something to be owned, remodeled, and commodified. The Deetzes embody the external pressures Adam and Barbara sought to resist in life: the commercialization of their private space. On a broader societal level, their intrusion and subsequent transformation of the Maitlands’ home highlight the consumer culture’s disregard for sentimental or historical values in favor of superficial change. The Maitlands’ horror at being unable to voice their objections is a deeply relatable fear—the sense of being invisible, powerless to influence the fate of something profoundly meaningful to them.

Colliding Realities: The Maitlands’ Futile Haunting

As Adam and Barbara struggle to come to terms with their untimely deaths and adjust to their ghostly state, they are confronted with an unexpected and unwelcome reality: the living owners who have purchased their beloved home. This part of Beetlejuice offers a rich juxtaposition between the Maitlands’ attempts to protect what they see as their sanctuary and the Deetzes’ desire to remodel the space according to their own tastes. It is a battle that serves as a metaphor for the larger theme of powerlessness, where an attachment to the past collides with inevitable change.

The Deetzes are portrayed as thoroughly urban, sophisticated, and more than a little self-absorbed. Delia Deetz, an aspiring artist, is entirely at odds with the rural serenity that the Maitlands cherished. Her disdain for the house is immediately apparent upon entering, as she sneers at its outdated décor and plans to alter nearly every aspect of it. This tension reflects a cultural conflict between the values of urban cosmopolitanism—preoccupied with aesthetics, status, and a cultivated cynicism—and the simpler, small-town appreciation the Maitlands have for authenticity and comfort. Delia’s insistence on redesigning the house, expressed through her interactions with Otho, serves as a pointed metaphor for the gentrification processes seen in many communities, where personal history is erased and replaced with something seemingly more stylish but lacking in emotional substance.

Lydia Deetz, by contrast, represents a fascinating middle ground. As a gothic teenager, Lydia embodies curiosity and a fascination with the macabre, appearing more in tune with the house’s spirit than her parents. Her openness and inquisitiveness sharply contrast with her parents’ superficiality, as they remain fixated on control and aesthetic dominance. Lydia’s character introduces a key philosophical perspective to the film—an embrace of the strange and unusual, standing in opposition to the resistance and denial exhibited by the adults around her. The use of a spider during her introduction subtly reinforces her connection to the uncanny and the otherworldly. A creature that inspires fear in most people is accepted by Lydia with casual nonchalance.

The Maitlands’ failed haunting attempts underscore the gulf between the living and the dead—a literal representation of their inability to interact meaningfully with the world they’ve left behind. Their efforts, meant to be terrifying and grotesque, fall entirely flat. The image of Barbara hanging in the closet and peeling back her skin in a horrifying display is completely ignored by Otho and Delia, who are far more horrified by the closet’s small size. This scene, undeniably comedic, reveals a deeper truth about human perception and indifference—people often see only what they want or are conditioned to see. The Maitlands’ attempts to reclaim their living space are thwarted not by a lack of creativity but by the Deetzes’ steadfast refusal to acknowledge anything that doesn’t fit within their worldview.

Otho, the Deetzes’ interior decorator and the epitome of superficial taste, adds another layer to the clash of realities. His dismissal of the house as lacking “organic flow” and his cavalier decisions about color schemes further alienate the Maitlands. Particularly telling is his blindness to the haunting. Despite his later fascination with the supernatural—a trait revealed later in the film—his immediate role is to embody the banal reality the Maitlands cannot transcend. For Otho and Delia, the house is merely a project, a blank slate to be reshaped into something that reflects their current tastes, with no regard for its past significance or the spirits that may inhabit it. This is an allegory for how modern society often treats history—ready to erase what came before and paint over it with something more fashionable.

The dynamic between Delia and Charles Deetz further enriches the thematic complexity of this scene. Delia’s unwavering dedication to her artistic ambitions, even in the face of her husband’s pleas to preserve the house’s original charm, highlights a broader cultural critique of self-centered pursuits of personal expression at all costs. Charles, longing for the tranquility of rural life, represents an increasingly outdated desire for simplicity—a yearning consistently thwarted by Delia’s relentless ambition and need for aesthetic control. Their debate over whether to keep the library intact presents an intriguing compromise, highlighting the constant tension between preservation and reinvention—a conflict that mirrors the Maitlands’ own struggle for relevance.

The sequence culminates in Barbara’s frustrated outburst: “I’m gonna get her.” It captures her helplessness in the face of an unstoppable force. This line encapsulates the overarching theme of the Maitlands’ haunting journey: a desire for action thwarted by their inability to meaningfully influence their surroundings. Their haunting, intended as a powerful assertion of their continued presence, is ultimately reduced to a futile pantomime in the face of the living’s complete indifference.

Confronting Limits: The Maitlands’ Frustration and Fear

A pivotal moment in Beetlejuice is Adam’s frantic retreat to the attic, followed by Barbara’s desperate attempts to frighten Otho and Delia. Despite their grotesque efforts, it becomes clear that fear is an elusive tool for the couple. Their frustration over their inability to preserve their home is palpable, a frustration exacerbated by the practical limitations of their ghostly state. This sense of helplessness is further underscored when Barbara runs out of the house, only to stumble into the vast desert beyond the front door—a desert infested with monstrous sandworms. The desert serves as a visual metaphor for the void of their new reality; the world beyond their home is uninhabitable and perilous, emphasizing that their existence is now confined to the house. This desolate wasteland recalls mythological concepts of liminality—a space between life and death where familiar rules no longer apply, leaving only confusion and fear behind.

The sandworm, a massive predator with a second head concealed within its primary mouth, embodies unpredictability and lurking danger. In many ways, it symbolizes the fears the Maitlands must now confront—the fear of the unknown, the fear of losing control, and the fear of insignificance. The snake-like creature, effortlessly gliding through the sand of the afterlife, starkly contrasts with the idyllic, controlled environment the Maitlands once enjoyed in their rural home. As the couple rushes back to the safety of their house, slamming the door shut behind them, the scene highlights the restriction of their autonomy. Their actions are reduced to reflexive self-preservation rather than meaningful exertions of power.

The Maitlands’ inability to influence the Deetzes’ actions is also apparent during the dining table scene, where Delia, Lydia, and Charles casually discuss their plans for the house. Their conversation, tinged with dissatisfaction, perfectly conveys how each character adjusts—or fails to adjust—to their new life in the countryside. Lydia’s remark that her “whole life is a darkroom” is poignant, offering insight into her alienation, which contrasts sharply with her parents’ pursuit of artistic and material fulfillment. Lydia, seemingly the only one able to connect with the ethereal and strange, serves as a bridge between the living and the dead—a role she will fully embrace later in the film. Her statement is not merely adolescent melancholy but also an expression of her affinity for liminal spaces and her comfort in environments others might find unsettling.

Delia’s persistence in her sculpting, which she claims is “the only thing that makes me truly happy”, adds another layer to the recurring theme of ownership and space. Delia’s desire to impose her artistic vision on the Maitlands’ house is not merely a superficial endeavor but an assertion of her identity in a space she now claims as her own. The cranes outside, tools of transformation, become symbols of modern intrusion—they embody society’s tendency to repurpose and reshape, often with little regard for the existing value or history of what is being replaced. For Adam and Barbara, watching these machines and the renovations directed by Otho feels like witnessing the erasure of their lives. Unable to intervene, they are relegated to mere spectators of their own impermanence.

The discovery of Betelgeuse’s advertisement—a “bio-exorcist” service—introduces a new dimension of possibilities for Adam and Barbara. This moment serves as a turning point in their battle against the Deetzes, hinting at how far they are willing to go to reclaim a semblance of their former lives. The fact that Betelgeuse markets himself as a specialist for assisting the recently deceased reveals a cynical twist on the bureaucratic nature of the afterlife. Even in death, the Maitlands must rely on dubious services and manipulative figures to navigate their situation. This underscores a darkly comedic aspect of the film: death does not signify the end of one’s troubles but merely ushers in a new set of perplexing challenges requiring questionable solutions.

The Allure of the Unknown:

The Maitlands and Lydia's Convergence

What begins as another chaotic day of home renovations for Charles, Delia, and their crew takes an unexpected turn when Lydia first encounters the ghostly presence of Adam and Barbara. Lydia’s discovery of the Maitlands lays the foundation for their eventual alliance and highlights the fragile boundary between the two worlds—a boundary that only Lydia seems willing or able to cross.

The scene opens with Charles attempting to find some semblance of peace amidst the ongoing renovations, only for the chaos to escalate as one of Delia’s sculptures crashes through the kitchen window. Delia’s exasperated reaction, shouting, “This is my art, and it is dangerous! Do you think I wanna die like this?!”, underscores her intense—albeit somewhat exaggerated—attachment to her artistic identity. This moment humorously emphasizes Delia’s detachment from her surroundings and her inflated sense of self-importance, as though even death should respect her art. It also serves as a commentary on the self-absorption of the living, who remain too engrossed in their personal dramas to recognize what lies beneath.

Meanwhile, Lydia’s photographic exploration of the house takes a mysterious turn when she spots Adam and Barbara peering out from the attic window. This sighting marks the first time Lydia directly perceives the Maitlands’ presence. Lydia has always been portrayed as an outsider—her black clothing, gothic aesthetic, and morbid curiosity set her apart from her own family. The fact that she is the first to notice the ghosts confirms her unique sensitivity to the “strange and unusual.” Lydia possesses an innate openness that allows her to perceive what others cannot. While her family is preoccupied with superficial concerns, Lydia’s interest in the esoteric enables her to connect with the unseen. Her discovery is interrupted by realtor Jane, whose clumsy intrusion provides Lydia with the literal—and metaphorical—key to uncovering the attic’s secrets.

The sequence involving the master key captures the tension between discovery and concealment. As Lydia attempts to enter the attic, Adam and Barbara are forced into physical resistance, desperately trying to keep her out. The attic door’s symbolism is significant, representing a barrier between two realms—the world of the living, filled with the Deetz family’s ambitions and desires, and the world of the dead, defined by the Maitlands’ struggle to maintain a sense of belonging. The attic becomes a liminal space, hovering between life and death, where connection is possible but hindered by fear and misunderstanding. During this moment, Betelgeuse’s commercial plays—a bizarre, almost surreal interjection that contrasts sharply with Adam and Barbara’s earnest attempts to protect their home. The commercial’s garish tone foreshadows the chaotic element Betelgeuse will soon bring to the story, standing in stark opposition to the Maitlands’ naive and well-meaning efforts to defend their space.

The “draw a door” scene adds another layer to the film’s exploration of liminality. When Adam draws a door with chalk, it feels almost like a ritual—a blend of childlike simplicity and supernatural summoning. The green light emanating from the door as it opens evokes an ethereal, otherworldly presence that is both alluring and menacing. This marks an active step for the Maitlands to embrace their ghostly reality rather than merely react to it. By walking through the door, they transition from passive inhabitants to participants in the strange world of the undead, even as they remain uncertain about what awaits them on the other side. Lydia’s observation of the green light piques her curiosity, signaling her growing proximity to the world of the dead—a realm she approaches with fascination rather than fear.

The contrast between Charles, leisurely flipping through a birdwatching book downstairs, and Lydia’s desperate attempts to make sense of what she has seen reflects their family dynamic. Charles’s disinterest in Lydia’s experiences underscores the generational and emotional divide between them. His focus on birdwatching—a calm, contemplative activity—stands in stark contrast to Lydia’s urgent need to process the unsettling events unfolding around her. Lydia’s line, “Maybe you can relax in a haunted house, but I can’t,” poignantly illustrates her alienation within her own family. It speaks to a deeper psychological conflict—while surrounded by people, Lydia remains profoundly alone in her experiences and perceptions. Her willingness to engage with the supernatural and accept the uncanny, rather than deny it, sets her apart from her family’s resolute ignorance.

The Bureaucracy of the Afterlife: Adam and Barbara’s Journey

The afterlife in Beetlejuice is not portrayed as a realm of peace or rest but as a complex, bureaucratic nightmare—one that mirrors the frustrations of the living world in an almost Kafkaesque way. This portion of the film, set in the surreal waiting room and later in the offices of the afterlife, captures the Maitlands’ confusion and helplessness as they navigate the bewildering system that governs existence after death. Through its exaggerated absurdity, Burton delivers a darkly comedic critique of societal institutions and their impersonal treatment of individuals, extending even beyond death.

When Adam and Barbara arrive in the peculiar waiting room, they are immediately confronted with the baffling nature of the afterlife. The green-skinned, pink-haired receptionist embodies the archetypal dismissive bureaucrat. Her sardonic attitude and pointed remarks about their lack of an appointment amplify the Maitlands’ feelings of confusion and disempowerment. The bureaucracy of the afterlife comes with vouchers, appointments, and caseworkers—all of which imply that the dead must now conform to yet another impersonal system, governed by rules and restrictions they neither understand nor control. The irony of needing a manual for navigating the afterlife, titled “Handbook for the Recently Deceased,” underscores this dehumanizing aspect. Even in death, the Maitlands must overcome a series of administrative hurdles, turning the afterlife into a tedious experience akin to dealing with insurance claims or government agencies.

Barbara’s whispered question to Adam — “Is this what happens when you die?” — perfectly encapsulates their mounting disappointment. Her expectation of something meaningful or at least comprehensible has been shattered by the reality of an afterlife filled with paperwork and bizarre creatures. The receptionist’s darkly humorous comment about her own death—how she might have avoided it had she known what awaited—offers a stark commentary on the supposed finality of death. Instead of providing closure, the afterlife is chaotic, fraught with strange new challenges, and far from the peaceful rest one might anticipate. Burton upends traditional notions of the afterlife, presenting a world that is banal in its bureaucracy yet bizarre in its visual design, from the green-skinned staff to the grotesque inhabitants of the waiting room.

As the Maitlands are led deeper into the “Office of the Dead,” they encounter skeletal employees and janitors tirelessly working, offering an absurd glimpse into an afterlife modeled after a near-capitalistic work ethic. This depiction raises broader philosophical questions about the meaning of existence after death. If the afterlife merely entails more work—more responsibilities without the physical comforts of the living—what does that say about humanity’s pursuit of purpose? The absurdity of clerical skeletons dutifully performing mundane tasks hints at a cynical view of existence, both in life and death, where the cycle of responsibility and monotony continues indefinitely.

Juno, the Maitlands’ caseworker, adds another layer to this critique. Juno embodies the impersonal efficiency of a bureaucrat, showing little regard for Adam and Barbara’s emotional state or predicament. Her brusque demeanor, exemplified by her cold remark, “What did you expect? You’re dead!”, reveals a pragmatic attitude that dismisses their plight as irrelevant to the bureaucratic processes of the afterlife. This reaction mirrors the disappointment many people face when dealing with unsympathetic systems—institutions designed to operate without regard for personal concerns. Barbara’s complaint about the Deetzes’ “terrible taste” and her suggestion that they might coexist in the house if they weren’t so different hints at a deeper longing for understanding and harmony—an idea that Juno quickly dismisses.

Juno’s warning about Betelgeuse introduces a foreboding element to the narrative. Her reluctance to even utter his name, opting instead for euphemisms, underscores the chaotic and unpredictable nature Betelgeuse brings to the table. He represents everything Juno—and by extension, the bureaucratic afterlife—cannot control. As an anarchic force, Betelgeuse operates entirely on his own terms, disregarding the rules and acting as a wildcard. This warning highlights the potential danger of deviating from the structure imposed by the bureaucracy of death, while also hinting that strict adherence to the rules may not be enough for Adam and Barbara to achieve their goals. They must decide whether to play it safe or take a risk—between the rigid structure of bureaucracy and the uncertainty of aligning with a rogue element like Betelgeuse.

When Juno vanishes in a puff of smoke, it becomes clear that Adam and Barbara are entirely on their own. The closing door behind them signifies that they must now make their own decisions in this unfamiliar territory. The film contrasts the human desire for guidance and structure with the unpredictability of the afterlife. Juno’s departure leaves the Maitlands with no choice but to navigate the system on their own, potentially embracing unconventional solutions to their predicament.

The juxtaposition of the Maitlands’ confusion with Lydia’s exploration of the attic reinforces the theme of seeking knowledge and connection. As Lydia flips through the “Handbook for the Recently Deceased,” her actions suggest a growing fascination with and potential understanding of the spirit world. Lydia’s curiosity signals her willingness to bridge the gap between the living and the dead, highlighting her unique role as someone able to engage with both realms.

Ghosts in Sheets: The Maitlands’ Failed Haunting Attempt

After Juno departs, Adam and Barbara find themselves in a liminal state, ironically haunted by their inability to effectively haunt. This part of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice captures their earnest but misguided attempts to scare the Deetz family—a venture that falls hilariously flat. The sequence serves as a darkly comedic critique of the Maitlands’ limitations in their ghostly form. Despite their intent to intimidate, their antics reveal a complete lack of understanding of the living world, underscoring the broader theme of their existential powerlessness.

The haunting begins innocently enough, with Adam and Barbara draping themselves in white sheets—a visual trope deeply ingrained in pop culture but entirely ineffective in this context. Their ghostly disguise, reminiscent of old-fashioned Halloween costumes, symbolizes their inability to adapt to the demands of their new, posthumous existence. The sheets, intended to inspire fear, instead evoke a sense of whimsy—a simplicity that renders them more comedic than terrifying. This contradiction reflects the Maitlands’ enduring naivety even in death, highlighting their struggle to grasp the reality of their situation.

The visual and auditory disconnect between the Maitlands’ efforts and the Deetz family’s reactions further emphasizes their ineffectiveness. When they attempt to scare Charles, he reacts with complete indifference, dismissing the apparitions as a prank orchestrated by his daughter, Lydia. This misinterpretation isn’t just a joke—it symbolizes the dead’s inability to penetrate the mindset of the living. Charles is so engrossed in his conversation with Maxie Deen and his own pursuit of profit that he doesn’t even register the presence of ghosts as a legitimate threat. The modern obsession with material gain and worldly concerns renders the supernatural meaningless, effectively stripping the Maitlands of the power traditionally wielded by spirits.

The following scene, in which Barbara and Adam enter Delia’s room and moan at the foot of her bed, continues this theme of failure. Delia, sedated by her medication, doesn’t even notice their presence. Burton employs dark humor here to emphasize the absurdity of their situation; even in their most exaggerated ghostly form, the Maitlands are utterly incapable of inspiring fear or even drawing attention. Their attempts are inherently anachronistic, relying on outdated ghost clichés that feel completely out of place in the modern, self-absorbed world of the Deetz family. Barbara’s exasperated admission that she feels “stupid” captures the futility of their efforts, while Adam’s insistence that they must persist if they want to drive the Deetzes out highlights their desperate need to reclaim their space, even as their attempts seem increasingly hopeless.

Lydia’s encounter with the ghosts is perhaps the most significant moment in this scene, as it marks the first genuine interaction between the Maitlands and someone who can perceive them. Initially mistaking the moaning for sexually suggestive noises, Lydia’s irritation shifts to curiosity when she sees the sheet-clad ghosts. Her Polaroid photos become a moment of revelation as she notices the figures lack feet—a telltale sign that they are not her parents in disguise. Lydia’s casual confrontation with Adam and Barbara, along with her fearless questions, represents a stark inversion of the typical ghost story. Instead of screaming or fleeing, Lydia is intrigued. She lifts the sheets to see the people behind the haunting, and her lack of fear visibly disappoints Adam and Barbara.

This scene further develops Lydia’s character as someone innately attuned to the macabre. Her admission that she is “strange and unusual” cements her as the only member of the Deetz family willing to recognize the ghosts for what they are. Lydia’s status as an outsider, marked by her gothic attire and fascination with death, allows her to communicate with Adam and Barbara in a way other characters cannot—or perhaps will not. This element touches on a philosophical level, suggesting that true connection often requires a willingness to embrace the unconventional or uncomfortable. Living on the fringes of her own family’s life, Lydia finds herself aligned with the Maitlands, who are similarly displaced within their own home.

Delia’s oblivion, induced by her Valium-induced slumber, adds another layer of satirical commentary on modern life—the tendency to numb oneself through consumption, whether material or pharmaceutical, dulls the world’s experiences, even those that are otherworldly. Delia’s indifference epitomizes the living’s general disregard for the supernatural in Burton’s vision of the afterlife, where even death struggles to command attention in a world overwhelmed by self-absorption and artificial distractions.

Summoning Chaos: The Maitlands Meet Beetlejuice

This pivotal section of Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice captures a defining moment in the Maitlands’ journey through the afterlife: their first encounter with the unpredictable, anarchic figure known as Beetlejuice.