Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

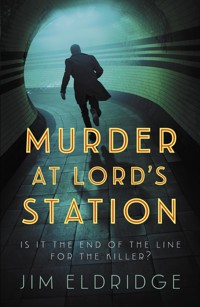

- Serie: London Underground Station Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

London, March 1941. The Blitz continues to cast a shadow over the city's brightest spots such as the Café de Paris. Having narrowly escaped a devastating bomb attack on the nightclub, Detective Chief Inspector Coburg and Sergeant Lampson are called to the disused Lord's Underground station where the body of a man has been discovered. The dead man was beaten to death by what may have been a cricket bat. Is he linked to the British Empire XI, made up of players from Great Britain and far-flung corners of the globe, who are playing at the world-famous Lord's Cricket Ground? Coburg and Lampson are certainly put in a spin by this complex case.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 420

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

MURDER AT LORD’S STATION

JIM ELDRIDGE

4

5To my wife, Lynne, who has been my rock and my support for so many years.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

London, Saturday 8th March 1941

Outside in the streets in and around Leicester Square, the bombs fell, bringing their nightly destruction to London. Inside the Café de Paris, deep beneath a cinema in Leicester Square, Rosa Coburg did her best to ignore the noise and vibrations as she played the closing number of her set at the club’s piano. She was glad she’d chosen a loud, raucous song, ‘When the Saints Go Marching In’, because one of her favoured gentler, slower numbers, such as Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘Georgia on My Mind’ or ‘Stardust’, would have been all but drowned by the bombing. With ‘Saints’, the sound of the bombing almost gave a deep bass musical counterpoint to the rhythm.

Rosa ended with a rousing change of chords, and then stood and responded with smiles and bows to the thunderous applause from the packed audience.

Martin Paulson, the genial compere, stepped forward into the spotlight, gesturing towards Rosa. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, let’s hear it once again for the fabulous Rosa Weeks!’

At this, the audience rose to their feet, applauding. Rosa bowed again, then moved out of the light to join her husband, DCI Edgar Coburg, at his table. 8

‘Wonderful.’ Coburg beamed. ‘You slayed them.’

In the spotlight, Paulson was addressing the audience. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, there will be a short break while we reassemble the band on stage for their next set. Mainly because we’ve got to find them.’

There was genial laughter at this, then Paulson continued, ‘But do, please, order your drinks now, and shortly you’ll be listening once again to the magic sound of the brilliant Ken Snakehips Johnson and his West Indian Dance Orchestra.’

With that, Paulson moved out of the spotlight and joined Rosa and Coburg at their table.

‘That was superb,’ he enthused. ‘Rosa, you are a star! Are you sure you can’t stay and do another number with Ken and the boys?’

‘I’d love to,’ said Rosa apologetically, ‘but I’ve got to be up early tomorrow morning. I’m on the early shift for St John Ambulance.’ She stopped as another bomb struck somewhere not far away, then said, ‘After tonight’s raid I’ve got an idea we’re going to be busy. But I promise that tomorrow night we’ll come back, as punters, and I’d love it if I could do something with the boys.’

‘Me and the boys would love it, too,’ said the smooth voice of Snakehips as he appeared at their table. ‘Gal, you are smokin’!’

Rosa gave the tall, slim man a hug. ‘You, too, Ken. We’d love to stay on tonight, but seriously …’

‘I know,’ said Snakehips ruefully. ‘It’s your wartime duty.’ He turned to Coburg and held out his hand. ‘Edgar, my man, you are one lucky dude, and I thank you both for tonight.’

Edgar shook the young man’s hand. ‘We’ll see you tomorrow, Ken. Have a good night tonight.’ 9

‘I hope so,’ said Snakehips. He looked at the bandstand and saw that most of his musicians had returned. ‘Hey, look at that, they’re here!’ he chuckled. ‘And that’s because they were hanging around listening to your set, Rosa, instead of heading to the john for a poker game like they usually do.’

As Snakehips joined his band on the stage, Paulson asked Coburg and Rosa, ‘How are you getting home? It’s not that safe out there.’

‘The same way we came, on foot,’ said Rosa. ‘We’ll be safe enough. It’s not far to our flat in Piccadilly, and we can always dodge in and out of doorways. After all this time, we’re getting used to it.’

‘I don’t think I can ever get used to it,’ said Paulson with a shudder. ‘Take care, and God willing I’ll see you tomorrow night.’

He shook their hands and they made their way to the cloakroom, collected their coats, then climbed the stairs to the exit to the street.

‘I think it might have died down a little,’ said Rosa.

There was the sound of an explosion followed by what sounded like a building collapsing.

‘It doesn’t sound like it to me,’ observed Coburg.

‘That was some distance away,’ said Rosa.

‘Yes, you could be right.’ Coburg nodded. ‘Alright, let’s go.’

They stepped out of the shelter of the club entrance, then moved along Coventry Street.

‘Maybe we should have brought the car,’ said Rosa.

‘This way’s safer,’ said Coburg. ‘We can keep moving and dodging.’

They were at the end of Coventry Street when there was a colossal explosion behind them, the force of it sending them 10stumbling, and then falling to the pavement. They got up and looked in the direction of the explosion.

‘The club’s been hit!’ exclaimed Coburg.

Sure enough, thick smoke was belching out of the entrance to the Café de Paris. Immediately, Coburg began running towards the club.

‘Watch out!’ warned Rosa.

‘There may be people in there who need our help,’ said Coburg, and kept running.

As he got close, some people spilt out of the club onto the pavement, coughing and choking and falling to the ground. Rosa ran to one and started checking for injuries.

‘I’m alright,’ said the man in between coughs. ‘At least, I think I am. But it’s carnage in the club. Bodies everywhere.’

Coburg made for the entrance and tried to find the stairs, but the smoke was so thick it was impenetrable. He took his handkerchief from his pocket and tied it behind his head so it covered his nose and his mouth, but his attempts to get down the stairs were hampered by the thick, acrid, black smoke, which completely blinded him.

He stumbled back out into the street.

‘It’s no good,’ he told Rosa in between bouts of coughing. ‘The smoke’s so thick in there you can’t see anything.’

‘But people could be alive in there!’ burst out Rosa.

‘The emergency services will have breathing apparatus and torches,’ said Coburg.

‘But when will they be here?’ she begged, nearly beside herself with agonised frustration.

Just then men appeared in fire brigade uniforms, hauling a hose. 11

‘Stand aside!’ shouted one. He pulled on his breathing helmet and made for the smoke-filled entrance, shining his powerful torch.

The men vanished into the thick, dense smoke. Coburg and Rosa attempted to follow them but were stopped by another fireman.

‘We have friends in there!’ Rosa appealed to him.

‘That may be, but it’s too dangerous,’ the man said.

‘I’m a volunteer for St John Ambulance,’ protested Rosa. ‘I might be able to help.’

‘You might also be killed. There’s no way of knowing what damage there’s been. The roof might be about to collapse. In fact, the whole building above it could fall down.’

‘But you’re going in,’ protested Rosa.

‘Only in as far as we can, and we’ve got breathing apparatus,’ said the man. ‘Now, move back. There could be another bomb in there, primed to go off. We need the entrance clear.’

Coburg took Rosa’s arm and gently pulled her back.

‘We can’t do anything,’ he said. ‘We’d only be a hindrance, in the way. If there is anyone alive, they’ll find them. We won’t be able to.’

‘In that case I want to wait here,’ she said. ‘I want to find out who’s survived, and who hasn’t. I need to know what’s happened to them.’

‘We can’t,’ said Coburg.

‘These are my friends,’ Rosa appealed. ‘People I’ve played with for years. People I care for.’

‘It’s too dangerous out in the street,’ said Coburg. ‘The bombing’s still going on.’ 12

‘But I want to know!’ she stressed.

‘And I’ll find out,’ Coburg promised her. ‘But nothing’s going to be known for hours. They won’t even be able to see in there. I promise you, I’ll come back when it’s daylight. I’ll find out what’s happened.’

‘What do we do till then?’ she asked, looking desperately at the smoke that still billowed out of the club entrance.

‘We go home,’ said Coburg sadly.

She hesitated, then nodded, took his hand and walked with him along Coventry Street towards Piccadilly.

CHAPTER TWO

Sunday 9th March

Coburg and Rosa sat down to their breakfast porridge, Rosa watching the clock. She was due at the St John Ambulance station at Paddington at 7.30 a.m.

‘You don’t have to go in this morning,’ said Coburg. ‘After what happened last night, I’m sure the others will understand.’

‘No, I’m going in,’ said Rosa. ‘Last night made me even more certain I have to go in. There will be people all over London who’ll be needing ambulances after last night’s attack.’

They had the wireless on in the background tuned in to the BBC Home Service, listening in case there was any news on what had happened to the Café de Paris the previous night, but the only mention of the night’s bombing was that Buckingham Palace had been hit during the attack.

‘Nothing at all about the Café de Paris,’ sighed Rosa.

‘They don’t like to put out bad news,’ said Coburg. ‘They think it lowers public morale.’

‘Buckingham Palace being struck is hardly good news,’ said Rosa.

‘Yes, but they think it shows that the royal family are sharing in the war damage,’ said Coburg. ‘After I’ve dropped you off at Paddington, I’ll try and find out what happened to Ken and 14Martin and the others. If it’s good news, I’ll phone Mr Warren at the ambulance station and leave a message.’

‘And if it’s bad news?’

Coburg thought it over, then said, ‘I’ll let you know either way.’ He finished his porridge and looked at the clock. ‘Time to go.’

Coburg drove Rosa to the ambulance station in the police car he’d been allocated after he’d been barred from using his much-loved Bentley for official purposes because, as he was told, ‘it doesn’t look good for a detective to be driving around in an expensive car like that when the general public are restricted in their petrol usage’. Especially, it had been added, when the detective concerned is the Honourable Edgar Saxe-Coburg.

‘There’s a certain feeling of animosity towards the aristocracy by a large section of the public, especially with the rationing, which seems to affect the poor but not the wealthy.’

‘I’m not wealthy,’ Coburg had pointed out. ‘And I don’t consider myself as an aristocrat.’

‘Others do. Your older brother is the Earl of Dawlish with a country estate. You went to Eton. That makes you one of them.’

And so Coburg had garaged the Bentley.

After dropping Rosa off, Coburg drove to Leicester Square. He parked the police car and walked along Coventry Street to the Café de Paris. Or, rather, where the café had been, for now tape had been fixed across the entrance and a sign said Danger. No entry.

‘Awful, isn’t it, Mr Coburg,’ said a voice behind him.

Coburg turned and saw Jeff Watts, a waiter at the café. His face and clothes were still stained with smears of black smoke. 15

‘I was lucky, the fire brigade found me. I was in the kitchen when the bomb went off. They dragged me out.’ He shook his head, misery etched in his face alongside the stains. ‘I haven’t been home. I wanted to stay here. It was almost like I kept hoping they’d turn up.’ He let out a groan. ‘Ken’s dead. So’s Martin. Most of the band. Most of the customers who were nearest the bandstand. They reckon forty were killed and eighty injured, so I was one of the precious few who survived.’ He gave a sigh. ‘You and your wife were lucky. If you’d stayed another ten minutes you’d have been killed as well. That table where you were was flattened.’

‘We came back,’ said Coburg. ‘Rosa and I. We tried to get in to see if we could do anything, but the fire brigade stopped us.’

‘You wouldn’t have been able to do anything,’ said Watts. ‘The fire brigade were only able to do what they did because they had breathing apparatus and torches. As it was, they were still taking bodies and the wounded out at four this morning. They reckon the bomb that did it came down the ventilation shaft that runs through the cinema and came out in the club. That’s when it blew up.’ His face puckered up and Coburg could see he was about to start crying. ‘Bastards!’

‘Where did they take the injured?’ asked Coburg.

‘Some to UCH, some to Charing Cross, some to the Middlesex. The trouble was there were so many people wounded last night, all over this part of London, the hospitals couldn’t cope.’

Coburg looked around him, taking in the ruined buildings, the pavements burst open, the smell of burning and of death. 16

‘I’d better go and tell Rosa the bad news about Ken and Martin and the others,’ he said.

Watts nodded. ‘Give her my regards, Mr Coburg. You’ve got a good one there.’

Coburg nodded and walked to his car, his nostrils filled with the smell of destruction.

He then did a tour of the inner London hospitals, using his warrant card as a Scotland Yard detective chief inspector, to get a list of those who’d been admitted as a result of the bombing of the Café de Paris, as well as those who’d been killed and put into the hospital’s mortuary. Along with Ken Snakehips Johnson and Martin Paulson, there were plenty of names he recognised among the dead. Many he didn’t, but those he felt had been the customers who’d been caught in the blast. The musicians in Johnson’s band were another matter, and Coburg knew how deeply Rosa would feel when she heard these names.

He looked at his watch and saw that it was half past one. Rosa was due to finish her shift at two. He pulled up outside a telephone box and dialled the St John Ambulance depot. The phone was answered by Chesney Warren.

‘Mr Warren, it’s Edgar Coburg. Is Rosa there, please?’

‘She’s just pulled in to the yard.’

‘Would you let her know I’m in the area and I’ll come and pick her up.’

‘No problem.’ There was a pause, then Warren asked, ‘Rosa told us about last night. Are you alright?’

‘We’re getting there,’ said Coburg. ‘I’ll see you shortly.’

When Coburg pulled into the yard, Rosa was waiting for him outside the office. 17

‘What’s the news?’ she asked urgently as she got into the car.

‘It’s not good,’ said Coburg. ‘Do you want to leave it until we get home?’

‘Tell me now,’ she said.

‘Martin and Ken are dead, along with half the band.’

She slumped in the passenger seat, her hair falling down to cover her face.

‘Who?’ she asked.

Coburg took out the list he’d made from his visits to the hospitals and gave her the names of those who’d died. ‘Some of them are alive, but are still in hospital being treated.’ He then read that list of names to her.

‘So they made it,’ she said.

‘So far,’ said Coburg. ‘What do you want to do now? Go home, or go somewhere else? Maybe go for a drink?’

She nodded. ‘Yes, let’s go for a drink. We’ll raise a glass to toast Ken and the rest of those wonderful players we’ll never see again.’ She wiped her eyes. ‘God, I’m getting maudlin,’ she apologised.

‘It’s allowed,’ said Coburg.

He put the car into gear and drove off.

CHAPTER THREE

Monday 10th March

Coburg pulled up outside the small terraced house in Somers Town where his sergeant, Ted Lampson, lived with his young son, Terry. Immediately, Lampson appeared. Coburg vacated the driver’s position and moved to the passenger seat, and Lampson slid behind the steering wheel. It was their regular arrangement: Lampson loved driving but couldn’t afford a car of his own, so Coburg kept the police car at his block of flats in Piccadilly, and every morning drove it to Lampson’s house, and Lampson took over driving duties during the working day. Coburg had suggested once that Lampson could keep the car overnight, but Lampson had pointed out that Somers Town was an inappropriate place to leave any vehicle out at night, especially a police car. It was one of the poorest parts of London, adjacent to Euston station, and with a number of petty criminals living there. A car parked on the street overnight was very likely to be stolen, or – in the case of a police car – badly damaged. The fact that the driver was a police detective sergeant meant very little; the only cars that were safe on the streets of Somers Town were those owned by known and very dangerous criminals.

‘Terry alright?’ asked Coburg as Lampson drove off, heading for Scotland Yard. 19

‘Fine,’ said Lampson. Lampson was a widower and during the working week he took his eleven-year-old son to his parents’ flat just round the corner, where his parents gave their grandson breakfast and then took him to school. ‘The team played against a church team yesterday. St Adulphus. Won 2–1.’

Lampson and his fiancée, Eve Bradley, a teacher at Terry’s school, organised a Somers Town football team that played matches against other teams in the area, mainly from other schools, boys’ clubs and church teams.

‘How are plans for the wedding going?’ asked Coburg.

‘Awful,’ groaned Lampson.

Coburg looked at him in surprise. ‘Eve’s not having second thoughts?’

‘It’s not Eve, it’s her mother,’ groaned Lampson.

‘What’s the problem with her?’

‘Loads, but the main thing is she doesn’t think I’m good enough for her daughter. She’d always hoped that Eve would get hitched to this bloke Vic Tennant.’

‘Who’s he?’

‘He’s got his own business, a builder’s with a yard at the back of Euston station. Rolling in money, according to Eve’s old woman.’

‘Did Eve used to go out with him before you and her got together?’

‘No, but he was always hanging around, bringing presents. Eve kept giving them back to him and told him to stop, but he started giving them to her mum, Paula, and she lapped it up. Kept on at Eve that she ought to settle down with him, and even now she’s giving Eve the tearful earful about how good this Vic would be for her. What she means, of course, is how good 20he’d be for Paula.’ Her gave a sigh, then asked, ‘How was your weekend?’

‘Tough. We got caught up in the bombing at Café de Paris. Rosa did a set there, and we’d just left when the bomb hit it. It was lucky for us that Rosa was on early shift at the ambulance station on the Sunday morning, so we’d left early.’

‘Yes, I heard about it on the wireless,’ said Lampson. ‘They said it took a direct hit. Lots of casualties. You were lucky.’

‘Snakehips Johnson was killed, along with some of his band and customers. We’d been talking to Snakehips and the café’s owner, Martin Paulson, just a minute or so before we left.’

‘I’d have thought it would have been safe, being underground. Like being in a bomb shelter.’

‘That’s what we thought, but it seems the bomb came down a ventilation shaft into the club, where it blew up. Forty killed and eighty injured.’

Suddenly the car radio crackled into life. ‘Base to Echo Seven. Come in, Echo Seven.’

Coburg reached for the handset and spoke into the microphone. ‘Echo Seven receiving. Over.’

‘Echo Seven. Reports of a dead man at the entrance to Lord’s Underground station. Police constable in attendance.’

‘Received and understood, Base. On our way. Echo Seven over and out.’ He hung up the microphone. ‘Right, Ted, Lord’s station it is.’

‘Sure they got it right?’ asked Lampson. ‘Lord’s was shut down a year ago. They might mean St John’s Wood. That’s the one that serves Lord’s Cricket Ground now.’

‘A constable’s in attendance. I’m sure he knows which station he’s at,’ said Coburg. 21

‘Another disused Underground station,’ sighed Lampson. ‘We’re getting a lot of these lately.’

‘It’s the Blitz,’ said Coburg. ‘They need somewhere for people to go to be safe from the bombing.’

They pulled up outside the closed-up Lord’s Underground station, where a uniformed constable was standing by the closed doors and another man was bending over a body lying on the pavement.

‘Looks like Dr Welbourne is here ahead of us,’ said Coburg.

Dr Welbourne looked up as the two detectives neared him.

‘What have we got, Doctor?’ asked Coburg.

‘We have a dead man,’ said Welbourne. ‘As you’ll see, he’s black, which is a bit of a rarity.’

Coburg and Lampson looked at the dead man. He was, indeed, black.

‘Any idea who he is?’ asked Coburg.

‘No identification on him,’ replied Welbourne. ‘No wallet or anything else.’

‘So, possibly a mugging?’

‘That would be speculation,’ said Welbourne. He pointed to the pavement on which the dead man lay. ‘One thing I’m sure, he wasn’t killed here. The lack of blood around him shows that. What I can tell you is he was beaten to death by some savage blows about the head.’ He indicated the dead man’s head where the skin had been lacerated beneath his hair, bloody gashes evident. ‘I may be wrong, but it wouldn’t surprise me to find the weapon was a cricket bat.’

‘A cricket bat?’ repeated Coburg, surprised.

Welbourne pointed to some splinters of wood he’d taken from 22the wounds to the man’s head. ‘If I’m not mistaken, these splinters are willow that’s been treated.’ He added, ‘My father works for a firm that makes cricket bats. But I may be wrong. I’ll be able to confirm it or not once I’ve looked at them under a microscope.’

‘If you’re right, it’s very appropriate him being found at Lord’s,’ said Coburg. ‘So, there could be a cricketing connection?’

‘Possibly,’ said Welbourne. ‘Although it may be a deliberate red herring to try and confuse any investigation. After all, a man beaten to death with a cricket bat – if that’s what it was – and his body dumped outside Lord’s Underground station seems a bit obvious. The other thing is he’s been badly beaten. Some of his fingers are broken. Again, I’ll be able to let you have more details once I’ve examined him properly.’

Coburg looked at the constable, who was standing watching, taking in the conversation between the doctor and the detectives.

‘Were you the one who found the body, Constable?’ asked Coburg.

‘Constable Riddick, sir,’ said the constable, snapping to attention and saluting. ‘From St John’s Wood station. And no, sir. I was first on the scene, but the man who discovered the body was a bloke on his way to work, and he came and found me. This is my regular beat, you see, sir, around this area. I asked him to stand by the body while I called it in to my station, then I stayed here to wait for you and the doctor to arrive.’

‘Have you got the name of the man who found the body?’

Riddick checked his notebook. ‘His name’s Henry Duggan. He lives near Lord’s Tube station. He works at a local butcher’s, Dorset’s.’ He passed Coburg a leaf torn from his notebook on which he’d written the man’s name and address, and that of Dorset’s the butcher’s. ‘Here are his details, sir.’ 23

‘Did he say at what time he found the body?’

‘It was just after eight o’clock.’

‘Thank you, Constable. That’s very efficient.’ Coburg looked at Welbourne. ‘Have you nearly finished here, Doctor?’

‘I’ve done just about as much as I can out in the street,’ said Welbourne. ‘I’m just waiting for an ambulance to arrive to take the body to UCH. Once I’ve got him on a table I’ll be able to tell you more about him, approximately when he died, and if it was the blows to the head that killed him, or something else.’

Coburg nodded. ‘In that case we’ll see you later at UCH.’ He turned to PC Riddick, and said, ‘I think you can return to your duties now, Constable. But well done for holding the fort until we arrived.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Riddick, and he gave another smart salute, and then marched off.

‘A good bloke,’ commented Lampson.

As he followed Coburg towards their waiting car, he said, ‘You look like you’ve had a thought, sir. About the dead man, I mean.’

Coburg nodded. ‘When I saw he was black my first feeling was that he could have been a musician. There’s quite a few musicians from the West Indies in London at the moment with so many British musicians away in the services. People like Snakehips Johnson and his band. But then I got to thinking about the cricket aspect.’

‘That a cricket bat may have been the weapon?’

‘That, and the fact it happened here, by Lord’s Cricket Ground. I wondered if the dead man could be associated with the British Empire XI.’

‘The who?’ asked Lampson.

Coburg smiled. ‘I guess you don’t follow cricket.’ 24

‘Not really. Football’s my game.’

‘The British Empire XI is a team made up of cricketers from Britain and far-flung parts of the Empire, including the West Indies. They’re here to play against different English cricket teams. Just like the football season’s been abandoned because of the war, it’s the same with cricket. It’s a chance to see top-class cricketers in action.’

‘But without knowing who this dead bloke is, there’s not much chance of finding out if he’s part of this lot,’ pointed out Lampson. ‘He could be just anybody.’

‘If I’m right about this, I think I know someone who might be able to help.’

‘Who?’

‘My brother, Magnus. He’s a cricket devotee, and also a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club, which owns Lord’s.’

‘So he might know this bloke?’

‘He might. Let’s head back to the Yard and I’ll give him a ring and arrange for him to meet us at University College Hospital.’

As Lampson drove them to the Yard, Coburg filled his sergeant in on why he thought Magnus might be able to help them. ‘He knows everyone in the cricket world. He was also a superb cricket all-rounder. Although Magnus only played as an amateur, he could have been a professional. He appeared regularly for Eton in the Eton v Harrow match, and was usually either top scorer or took the most wickets. He may not know our victim at all, but there’s a chance, and – if he does – this will be quicker than going through the usual channels.’

‘Is he in London?’ asked Lampson. ‘I thought he was at the family stately home in the country. Dawlish Hall.’

‘Not while this series of cricket matches are happening. He 25and Malcolm have got their own seats at Lord’s.’

‘Malcolm likes cricket as well?’ asked Lampson.

‘Not as much as Magnus, but he’s got an encyclopaedic knowledge of who played for who and when, and their scores.’ He grinned. ‘It irritates Magnus no end.’

It had been a busy morning for Rosa and her co-driver, Doris Gibbs. Their first call had been to a woman with a suspected heart attack. No sooner had they delivered her to the nearest hospital, than they got a radio message instructing them to go to a fallen building. There, they found an elderly man who’d been trapped in the cellar of his house when it had collapsed following the bombing on Saturday night. He’d been found on Monday morning by a team of rescuers who’d responded to reports of knocking from beneath the rubble. They’d cleared the rubble, exposing a wooden floor, and found a trapdoor. They’d forced the trapdoor open, and a torch shone into the darkness beneath illuminated a man in his sixties called Percy, who told them, ‘I think my leg’s broke.’

Rosa and Doris arrived and fixed a temporary splint around the man’s broken leg, then – with the help of members of the fire brigade who’d turned up – managed to get the stretcher holding the injured man up the rickety wooden steps and out through the trapdoor, and into their ambulance.

‘It’s lucky they put that radio in our vehicle,’ said Doris. ‘Even though it means we don’t get a break between calls.’ Gradually the St John Ambulance were able to put two-way radios in more and more of their vehicles, speeding up the time they could attend to an urgent call.

‘How are you doing?’ asked Doris. 26

‘Better than I was yesterday,’ said Rosa. ‘Being busy helps keep me from thinking about it too much.’

She was referring to the bombing of the Café de Paris, an event that still haunted her.

‘And Edgar?’ asked Doris.

‘He throws himself into his work even more than I do,’ said Rosa. ‘Which is a good thing for him. Mind, he wasn’t as close to Ken and the others as I was. I’d played with them for years; they were a really good bunch, as well as being fantastic musicians.’

She slowed down as they neared a junction where a double-decker bus was lying on its side.

‘We’d better go back and take the long way round,’ she said.

‘I’ll go and tell Percy what’s happened and see if he’s alright,’ said Doris.

Doris moved to the back of the ambulance where their patient lay, holding on to handles to keep her balance due to the ambulance rocking slightly as Rosa reversed it and then did a three-point turn. Doris arrived beside the elderly man.

‘There’s a bus been blown over,’ she explained. ‘We’ve got to take a different route to the hospital. Are you managing?’

Percy nodded. ‘What you gave me has helped with the pain,’ he said. ‘Thanks.’

‘It’s what we do,’ said Doris. ‘Hopefully our way will be clear this other way, so we’ll soon have you in hospital.’

‘Six months,’ groaned Percy unhappily.

‘What?’ asked Doris.

‘Six months,’ repeated Percy. ‘That’s how long this bombing’s been going on. Every night, and sometimes during the day. How much longer is it going to go on for?’

‘Lord alone knows,’ sighed Doris. 27

At the Yard, Coburg telephoned Magnus’s London flat. As usual, the call was answered by Magnus’s valet, driver and general factotum, Malcolm. The two men had been in the trenches together during the First War, Magnus in command of a unit and Malcolm his batman. Magnus credited Malcolm with saving his life under fire on at least three occasions.

‘Once I was all tangled up on barbed wire, and Malcolm cut me free while Jerry kept up heavy fire on our position with their damned machine guns. Malcolm was hit twice. If it hadn’t been for him, I’d have been dead.’ Then he’d added, ‘Mind, I don’t talk about it to him. Don’t want him to get a swelled head.’

‘The Earl of Dawlish’s residence,’ Malcolm announced in his most official manner.

‘Malcolm, it’s Edgar. Is Magnus there?’

‘He’s in the bath at the moment, Mr Edgar. Is it urgent?’

‘Not urgent enough to get him out of the bath for. But when he’s finished, could you bring him to University College Hospital.’

‘Certainly. I believe he’s nearly finished. He’s stopped that infernal singing of his. Can I tell him what it’s about?’

‘There’s a dead body I’d like him to look at. Along with you, of course. The doctor who examined him believes he was beaten to death with a cricket bat.’

‘A cricket bat!’ exclaimed Malcolm, his voice filled with outrage. ‘Is nothing sacred?’

‘We’re not sure. The thing is, we don’t know who he is and we hope you two might know him.’

‘We’ll be with you shortly, Mr Edgar. It’s the mortuary at UCH, I presume?’

‘It is. We’ll see you there, Malcolm.’

CHAPTER FOUR

Coburg and Lampson found Dr Welbourne at work on another cadaver’s organs when they arrived at University College Hospital’s mortuary.

‘I haven’t had a chance to get round to your man yet,’ said Welbourne, pointing to where the dead man lay on a table covered by a sheet. ‘I needed to get these bits and pieces examined to determine the cause of death of another victim.’

‘That’s fine,’ said Coburg. ‘In fact, it’s a stroke of luck because I’ve invited my brother, Magnus, to come here and take a look at him. We feel he might know who he is. If there is a cricketing connection, that is. He’s bringing his old friend, Malcolm, with him. And it’ll be easier for them to see if they recognise the dead man before you start slicing him open.’

‘The Earl of Dawlish.’ Welbourne nodded. ‘I saw him play once. He was using a bat my father had worked on. Superb batsman.’

‘Yes, well, he and his old army chum seem to know everyone in the cricket world.’

There was a tap at the door, then it opened and a white-jacketed porter peered in.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ he said. ‘There are two gentlemen to see you.’ 29

‘Please show them in, John,’ said Welbourne.

Magnus and Malcolm entered, and Coburg introduced them both to Welbourne.

‘Killed with a cricket bat, I understand,’ said Magnus.

‘That’s what it appears, although I’ll know more once I’ve opened him up and examined him,’ said Welbourne.

He walked to the figure lying on the table and pulled back the sheet to show the man’s head.

‘Good God, it’s Desmond Bartlett!’ exclaimed Magnus, obviously shocked.

‘You know him?’ asked Coburg.

‘Of course we know him!’

‘He’s Jamaican,’ added Malcolm. ‘One of their best bowlers. In fact, we saw him on Saturday.’

‘Where?’ asked Coburg.

‘At Lord’s, at the practice nets, along with some of his team-mates. We wanted to see how they shaped up.’ He looked ruefully down at Bartlett’s dead body. ‘What a tragedy!’

‘So he was part of the touring British Empire XI?’ said Coburg.

‘That’s not quite correct,’ said Malcolm. ‘The British Empire XI have yet to start the 1941 season. So far Bartlett’s been playing for the West Indies XI.’

‘Didn’t you see the one-day game they played against Pelham Warner’s XI at Lord’s?’ asked Magnus.

‘No, we were rather busy at that time.’

‘Learie Constantine was magnificent for the Windies. A complete all-rounder. Bowls as well as he bats. And Len Hutton was superb for Pelham Warner’s side.’

‘There was one oddity,’ interjected Malcolm. ‘The Compton 30brothers both played in the match, but for opposing sides. Denis Compton was top scorer with seventy-three, and his brother Leslie was made an honorary West Indian for the day.’

‘We need to talk to the other players who were at that practice,’ said Coburg.

‘Your best bet is to talk to Ray Smith and C. B. Clarke,’ said Malcolm.

‘Ray Smith?’ Coburg frowned. ‘He’s the Essex all-rounder, isn’t he?’

‘He is,’ said Malcolm. ‘He’s also the captain of the Empire XI. C. B. Clarke is the vice-captain.’

‘I don’t know him,’ said Coburg.

Both Magnus and Malcolm looked at Coburg in disbelief.

‘You don’t know who C. B. Clarke is?’ said Malcolm, shocked by Coburg’s ignorance.

‘Unlike you two, I have a full-time job that keeps me very busy,’ responded Coburg. ‘I’m aware of cricket when it happens, but I wouldn’t describe myself as an avid follower.’

‘Obviously not, if you don’t know who C. B. Clarke is,’ said Magnus, his tone heavy with disapproval. ‘Carlos Bertram Clarke. And, for the record, his team-mates call him Bertie. He’s from Barbados.’

‘When the West Indies played the Metropolitan Police at Imber Court, he took all ten wickets for just twenty-nine runs,’ added Malcolm. ‘He was there at the nets on Saturday, as was Ray Smith. If you want to know who else was, ask Ray and Bertie.’

‘You seem to know a lot about the team,’ commented Coburg. ‘What about Desmond Bartlett?’

‘I remember he came over with the West Indies team 31in 1939,’ said Malcolm. ‘When they realised that war was imminent, some of the team returned to the West Indies, and some elected to stay here and join up in the forces. Bartlett was one of those who stayed. He joined the RAF as ground crew.’

‘Do you know where he was based?’

‘No, but I’m sure we can find out.’ He looked at Coburg and asked, ‘Where was he found?’

‘Outside Lord’s Tube station.’

‘Curiouser and curiouser,’ murmured Magnus.

After Magnus and Malcolm had left, Coburg asked Welbourne if he had any idea when the murder took place.

‘I won’t know until I’ve checked his stomach contents, worked out mealtimes, that sort of thing. But, from the degree of rigor mortis, I’m guessing between six o’clock and eight o’clock last night.’

Coburg thanked Welbourne, then he and Lampson made their way up from the basement to the street and their car. As they left the hospital, Lampson grumbled, ‘Bloody Arsenal.’

‘What have Arsenal got to do with it?’ asked Coburg, puzzled.

‘The Compton brothers, Denis and Leslie. It’s not enough they play for Arsenal in the football league, now it turns out they’re both top-level cricketers. It ain’t right.’

CHAPTER FIVE

Coburg and Lampson returned to Scotland Yard, where they telephoned Lord’s, and after being passed from person to person they were eventually given the addresses and telephone numbers for Ray Smith and Bertie Clarke.

‘It seems that they are the main organisers for the Empire XI,’ said Coburg.

‘Hopefully they’ll be able to tell us all we need,’ said Lampson.

Coburg tried both numbers, but there was no answer to either.

‘We’ll try them again later,’ he said. ‘In the meantime, let’s go and have a word with Henry Duggan.’

Henry Duggan was a short, burly man working in the small room at the back of Dorset’s butcher shop, sawing up the carcases of lambs and pigs, and then chopping and slicing the pieces into smaller cuts to be displayed in the shop. He seemed grateful to step out into the small yard at the back of the shop to talk to Coburg and Lampson.

‘It’s hot work,’ he said, mopping the sweat from his brow with a large red handkerchief.

‘Your boss can still get hold of meat,’ noted Coburg. 33

‘He’s got a pal who’s got a smallholding in Essex,’ said Duggan. ‘He lets us have the occasional pig or lamb, but it’s not like before rationing came in. Then, there were five of us butchers here working on the carcases. Now, there’s just me and a bloke called Jerry who comes in a couple of days a week.’ He looked at the warrant cards that the two detectives held up for him. ‘I’m guessing this is about that bloke I found at Lord’s station.’

‘It is,’ said Coburg. ‘Can you tell us what happened?’

‘Sure. I was walking to work, same as I always do, and I saw this bloke lying on the ground by the entrance to Lord’s Underground. At first I thought he might be a drunk sleeping it off; you get them sometimes. Then I saw he was black, which was a bit unusual. But then I thought to myself, Lord’s, and I remembered that they were putting on this series of cricket matches, English Counties against the West Indians. So I wondered if he might be one of them. There’s been a few of them in the area, going to Lord’s to practise. I’m not a great cricket fan, football’s more my game, but I like to see top-class sports still taking place. Anyway, I went to him and gave him a gentle prod to wake him up, but he didn’t respond.’

‘Was he on his back or on his front?’

‘On his back, so I was able to check if he was breathing without turning him over. And he wasn’t. So I checked for a pulse, and there wasn’t one of them either. So I knew he was dead. I knew there was a local copper in the area, because I used to see him sometimes when I was on my way to work. Just to nod to, not to talk to. But I knew where he might be found. So I went to look for him. And, sure enough, he was there.’

‘Where?’ 34

‘Not far up Prince Albert Road. He looked like he was on his way to the zoo. So I told him about the dead bloke and he come along with me. Then he said he’d need to get Scotland Yard to call it in, so he asked me if I’d mind standing by the bloke while he made the call. And that’s all there was to it. I waited, and when he came back, I went to work.’

‘Did you notice if there was any blood on the ground by the body?’

Duggan shook his head. ‘No. I didn’t want to start pulling him around because I didn’t want to mess things up; I know the police like things left as they are till they’ve gone over them. But I had a quick look to see if there was any blood, or any indication of what might have happened, but there was none. Do you know yet how he died?’

‘He was struck on the back of the head,’ said Coburg.

‘Poor bloke.’

‘What time was it when you found him?’

‘Quarter to eight. It only took me five minutes or so to find the copper. Lucky he was right in the area.’

‘Thank you, Mr Duggan. You’ve been very helpful. Oh, and you were right about him being a cricketer.’

Duggan gave a smug smile. ‘It was him being at Lord’s made me think of it. I’d make a good detective.’

‘So, Bartlett was definitely killed somewhere else and then his body dumped,’ said Coburg as he and Lampson walked back to their car.

‘Why at Lord’s Tube station entrance?’ asked Lampson. ‘Someone trying to send some sort of message? Something to do with cricket?’ 35

‘Possibly,’ said Coburg.

‘In which case, why didn’t they dump him at Lord’s Cricket Ground itself?

‘Too many people there. The Tube station is closed down.’

‘It’s still odd,’ said Lampson.

‘I think it might help to find out a bit more about Lord’s station,’ said Coburg. ‘If anyone’s got the keys to it, if anyone ever goes in to check it, that sort of thing.’

‘Difficult to find out if it’s always closed,’ observed Lampson. ‘No one to ask.’

‘Yes there is,’ said Coburg. ‘The Railway Executive Committee offices at Down Street. Jeremy Purslake.’

‘Purslake?’ mused Lampson. ‘That’s the bloke we met over the dead Russian woman.’

‘That’s right,’ said Coburg. ‘If there’s anyone who seems to know everything about the railway systems in this country, it’s Mr Purslake.’

They drove back to Scotland Yard. Once more, Coburg tried the telephone number for Bertie Clarke, but again got no reply. Next, Coburg got the telephone operator to try the Railway Executive Committee, and when he was connected, asked to be put through to Jeremy Purslake.

There was a series of clicks on the line, then the operator said, ‘I have Mr Purslake for you, Chief Inspector.’

‘Thank you,’ said Coburg. ‘And thank you for taking my call, Mr Purslake, I know how busy you are.’

‘Never too busy to talk to you, Chief Inspector,’ said Purslake. ‘How may I help you?’

‘I’m afraid we have another dead body at a disused Underground station.’ 36

‘Oh dear,’ said Purslake. ‘On the platform, like last time?’

‘No. This one was left outside Lord’s station. A man.’

‘Murdered?’

‘Apparently beaten to death.’

‘How awful!’

‘I’m hoping you can help us.’

‘Certainly, but I’m not sure how.’

‘If you can let me know about the station. I know that it closed in 1939, once war was declared.’

‘Yes. In fact it’s got a bit of a convoluted history, which is why I’m able to tell you about it without needing to go into the archives. The station opened under the name of St John’s Wood Road in 1868. It was unable to cope with the large passenger numbers who used it to attend cricket matches at nearby Lord’s Cricket Ground. As a result, the station was demolished and reconstructed on a larger scale in 1925, opening under the name of St John’s Wood. In June 1939 it was renamed again, this time as Lord’s. In November 1939 a new Bakerloo line station named St John’s Wood was opened to relieve continuing increasing congestion at Lord’s station. With the advent of the Second World War, it was decided to close Lord’s station, initially for the duration of the war. However, the decision was made to shut the station permanently after the last train on 19th November 1939.’

‘I see,’ said Coburg. ‘Is it operating as an air raid shelter, like many other Tube stations?’

‘No,’ said Purslake. ‘That would require station staff to be on duty, and air raid precautions in that area are already being well taken care of. Members of the public have night-time access to St John’s Wood station, which is less than half a mile away from the old Lord’s station. Also, Marylebone Borough 37Council have constructed an air raid shelter in the crypt of St John’s Wood chapel.’

‘So at the moment, Lord’s station is shut up completely?’

There was a moment’s hesitation, then Purslake said, ‘To all intents and purposes. The staff at St John’s Wood have keys to the doors in case there’s an emergency. The same goes for another set of keys left at St John’s Wood police station.’

‘And have these emergency keys been used much?’

‘If they have, no one’s felt the need to advise us here at Down Street. My recommendation would to be make enquiries direct to the staff at St John’s Wood.’

Coburg looked thoughtful as he replaced the receiver.

‘Has he given you something to think about, guv?’ asked Lampson.

‘Not on purpose,’ said Coburg. ‘According to him, Lord’s station is officially closed and not in use, not even as an air raid shelter.’ He got up from his chair and said, ‘Purslake also told me that St John’s Wood Tube station have got keys to Lord’s. I think it might be worth our going to St John’s Wood and picking up the keys and having a nosy around, but first I think we need to check out Lord’s Cricket Ground itself. If Bartlett’s death is connected to cricket in some way, there might be some answers there.’

‘I’ve never been to Lord’s,’ said Lampson.

‘I haven’t been for some years,’ said Coburg. ‘In fact, I think the last time I was there it was to watch my late brother Charles play in an Eton and Harrow match.’

‘Charles? Not Magnus?’

‘No, Charles was younger than Magnus so he played more recently.’ 38

‘You never played?’

‘Not at that level. Anyway, I certainly haven’t been since it’s been taken over for the war effort.’

‘Who by? The army?’ asked Lampson. ‘I know they’re stationing troops on some football pitches.’

‘No,’ said Coburg. ‘The cricket pitch and the seating have been left alone so matches can still be played. But there are barrage balloons operated from there, and also part of the grounds has been given over to an RAF Aircrew Receiving Centre, where the new recruits come.’

‘With all that going on, will we be allowed in?’

Coburg smiled. ‘We will be if we have a member of the MCC with us.’ He picked up the phone. ‘I’ll see if Magnus and Malcolm are free. In which case, we’ll do Lord’s before we go to the stations at St John’s Wood.’

CHAPTER SIX

Magnus and Malcolm were waiting for them at the entrance to the cricket ground.

‘You’re in luck,’ said Magnus. ‘Ray Smith and Bertie Clarke are here, in the clubhouse. We’ve told them about poor Desmond Bartlett. They’re both absolutely shocked.’

‘We told them you were on your way,’ added Malcolm. ‘They’re looking forward to talking to you, answering any questions you have.’

As they walked towards the clubhouse, Coburg and Lampson looked up at the huge barrage balloons, the defence against low-flying enemy aircraft, floating in the sky above Lord’s, anchored to the ground by thick metal cables.

‘I see the place is well-protected,’ Coburg commented.

‘It needs to be,’ said Magnus. ‘You may remember that last October those swine in the Luftwaffe dropped an oil bomb onto the outfield at the Nursery End. It’s hoped that these barrage balloons will put a stop to that sort of thing. The last thing we want are bombs falling when a match is being played. They’re controlled by 903 Balloon Barrage Squadron located in the Nursery Ground.’

‘Where’s the Aircrew Receiving Centre?’ asked Coburg.

‘At the other end, past the pavilion. Most of the new recruits 40are billeted in the blocks of flats overlooking Lord’s.’

‘Luxury accommodation,’ commented Coburg.