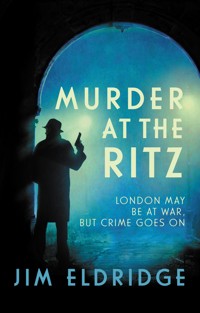

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hotel Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

August 1940. On the streets of London, locals watch with growing concern as German fighter planes plague the city's skyline. But inside the famous Ritz Hotel, the cream of society continues to enjoy all the glamour and comfort that money can buy during wartime - until an anonymous man is discovered with his throat slashed open. Detective Chief Inspector Coburg is called in to investigate, no stranger himself to the haunts of the upper echelons of society, ably assisted by his trusty colleague, Sergeant Lampson. Yet they soon face a number of obstacles. With the crime committed in rooms in use by an exiled king and his retinue, there are those who fear diplomatic repercussions and would rather the case be forgotten. With mounting pressure from various Intelligence agencies, rival political factions and gang warfare brewing either side of the Thames, Coburg and Lampson must untangle a web of deception if they are to solve the case - and survive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

3

MURDER AT THE RITZ

JIM ELDRIDGE

5

Once again, for Lynne, without whom there’d be nothing

6

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Tuesday 20th August 1940, London. 7.30 a.m.

The Hon. Edgar Walter Septimus Saxe-Coburg – better known to his colleagues at Scotland Yard as Detective Chief Inspector Coburg – pulled up in his Bentley outside the small terraced house of his sergeant, Ted Lampson, in Purchese Street, Somers Town. Lampson, a stocky, muscular man in his early thirties with a boxer’s face, a bent nose and one ear flattened, was standing on the pavement with his ten-year-old son, Terry. The boy was looking up beyond the silver barrage balloons that hung in the sky over London, tethered to the ground by their steel cables, staring at the air battle going on in the sky as two Spitfires attacked a German bomber.

Lampson hurried over to the car, a concerned look on his face.

‘What’s up, guv’nor?’ he asked. ‘I was just leaving to get the bus to the Yard.’

‘Which is why I called,’ said Coburg, getting out of the 8car. ‘Change of plan. We’ve got to go to the Ritz.’

Coburg was in his early forties, taller than his sergeant and dressed with more elegance – the sign of a good tailor. A streak of white ran from front to back at one side of his thick dark hair, the result of an old war wound.

Lampson’s face lit up into a smile. ‘For breakfast?’

‘You’ll be lucky,’ said Coburg. ‘You ought to get a phone put in, then I could have called you.’

‘Can’t afford one, guv,’ said Lampson. He turned towards his son and shouted, ‘You got your gas mask, Terry?’

Terry opened his jacket to show the gas mask in its holder dangling from around his neck.

Coburg gestured towards Terry, his turn now to look concerned. ‘You sure he should be standing there?’ he asked. ‘He should be at the shelter.’

‘I was just making sure he went,’ said Lampson.

‘Not well enough,’ commented Coburg.

‘That’s a Dornier!’ shouted Terry excitedly. ‘A Do 17. It carries over 2,000 pounds of bombs.’

As they looked up, one of the Spitfires let burst a tracer of bullets that ripped into one of the German bomber’s two engines, which suddenly poured smoke, first grey then black, and flames could be seen licking at the plane’s wing.

‘It’s going down!’ yelled Terry delightedly.

‘For God’s sake, get in the car!’ barked Coburg, pulling open the rear door.

As Lampson pushed his son into the rear of the car, Coburg asked: ‘Where’s the nearest shelter?’

A woman had appeared from the house next door.

‘What’s going on?’ she demanded. ‘What’s that posh car doing outside my house?’ 9

‘It’s an air raid, Mrs Smith,’ said Lampson. ‘Didn’t you hear the sirens?’

Mrs Smith looked at them, uncomprehending, then announced: ‘I haven’t got my hearing aid.’

With that she started to return to the house, but Coburg stopped her and steered her back towards the car.

‘It’s an air raid!’ he shouted.

He ushered her into the rear of the car next to Terry, pushed the door shut and slid behind the steering wheel, as Lampson got into the passenger seat.

‘Where’s the nearest shelter?’ Coburg asked again.

‘Maples depository, Pancras Road,’ said Lampson. ‘Just round the corner.’

Coburg looked out of his window and saw the German bomber, now engulfed in flames, hurtling down towards the ground.

‘It’s going to hit somewhere over the Caledonian Road,’ said Lampson.

‘If it’s still got its bomb load on it’s going to make a hell of a hole when it does,’ said Coburg. ‘I’m not taking a chance on another coming down before we get you to the shelter.’

He accelerated, taking care not to run into the pedestrians who were heading for the shelter on foot.

‘I’ve never bin in a Bentley before,’ said Terry. ‘You must have a lot of money, Mr Coburg.’

‘Don’t be cheeky, Terry,’ his father snapped at him.

‘I shouldn’t have left my hearing aid behind,’ said Mrs Smith. ‘I won’t be able to cope without it.’

‘I’ll look after you, Mrs Smith,’ Terry shouted to her.

Coburg pulled the car to a halt outside Maples large 10furniture depository, whose basement was doubling as an air-raid shelter. People were still hurrying in, guided by uniformed air raid wardens.

‘Get in there quick!’ said Lampson. ‘And look out for your gran and grandad! They’ll be looking after you.’

Terry opened the door and slid out of the car, then helped Mrs Smith out. Coburg waited until he was sure the pair had entered the depository before setting off again.

‘You should have sent Terry away like the other evacuees,’ said Coburg.

‘I did,’ said Lampson. ‘He went off with all the others, his name on a brown cardboard label pinned to his coat, but I brought him back two months later. The place he was staying in was rotten. The people treated him cruel, like an unpaid slave. I wasn’t having that.’

‘It’s still dangerous him being in London,’ insisted Coburg. ‘Haven’t you got family somewhere outside London you can send him to?’

‘No,’ said Lampson. ‘We’re all Londoners. I’ve got an uncle and aunt in Ramsgate, but they’re too old to handle Terry. I’ve also got a cousin in Kent, but as he lives near Biggin Hill that’s not a good idea at the moment.’

True, thought Coburg. The airfields of Kent were being bombed on a regular basis. It was a rarity that a German plane came as far as London, as that one had this morning. All the intelligence suggested that Hitler’s orders were to put the airfields out of action and destroy the RAF so that he could invade from the sea. Perhaps the pilot overshot his target.

‘I was thinking of joining the Local Defence Volunteers,’ said Lampson. 11

‘It’s called the Home Guard now, Ted,’ said Coburg. ‘Churchill renamed it. Anyway, I’d have thought you had enough to do already. You’ve got your job, and also your son to take care of.’

‘My mum and dad keep a good eye on Terry,’ said Lampson. ‘They do it during the day.’

‘Which is why he needs you when you’re not at work.’

‘Other blokes do it,’ countered Lampson.

‘Most of them are retired people. Former soldiers with time on their hands.’

‘Not all,’ said Lampson. ‘My neighbour was talking to me about the Somers Town Home Guard. He’s a plumber and he’s in it, and he’s married with five kids. He goes to all the sessions, the practices and meetings and that.’

‘With five kids he’s possibly glad to get out of the house,’ commented Coburg.

‘Yeh, but I feel I ought to be doing something for the war effort,’ said Lampson. ‘I tried to join up but they wouldn’t take me because of the fact that my wife had died, so I was Terry’s only parent.’

‘Those are the rules,’ said Coburg. ‘And quite right, in my opinion. Every child should have at least one parent living. What would it do for Terry if you went off in the army and got yourself killed?’

‘You can get killed here,’ insisted Lampson. ‘Fire-watching. I know of two blokes who became volunteer firemen and were killed when the building collapsed on them.’ He looked accusingly at Coburg as he added: ‘And I don’t know why you’re so against me serving, guv. You volunteered in the last lot.’

‘I did. And I got shot.’ Then he added, in a more conciliatory tone: ‘Not that that would have stopped me. The difference was that I wasn’t married, I had no children 12depending on me. We’re all doing our bit in different ways. Like now, we’ve got a dead body to take care of.’

‘It’s not the same, though, is it? If the Germans invade, we need men to stop them. And not just on the beaches, but in towns and cities. They reckon they’ll come down by parachute in their thousands.’

‘Yes, I agree, I think that’s likely,’ said Coburg. ‘And if it happens, I’ll be there too, with a gun and whatever else is to hand to defend us. At the moment, my faith is in the RAF blowing German bombers out of the sky and shooting down their fighter planes. So long as those boys can keep the Luftwaffe at bay, I believe Hitler will hold his invasion fleet back.’

‘His fleet’s all ready around Calais,’ said Lampson. ‘Hundreds of ships and thousands of soldiers. My uncle in Ramsgate says you can see ’em through a telescope.’

Coburg shook his head. ‘It’s twenty-five miles of choppy sea across the Channel, at risk from attacks by the air and our navy when they get close to the Kent coast. The Germans are methodical. I know, I fought them for nearly a year in the first lot. They don’t rush in unless they’re sure of victory. Hitler will put everything into trying to destroy the RAF, as he’s doing now, before he unleashes his invasion fleet.’ He gestured upwards with one hand. ‘Those are the guys who need our support. The ones in their Hurricanes and Spitfires riding shotgun on our behalf. At the moment they’re our first – and only – line of defence.’

CHAPTER TWO

Coburg led the way as he and Lampson passed through the main doors into the luxurious marble-floor foyer of the Ritz Hotel, then made for the long, curving glass-topped desk to the right. George Criticos, the hall porter, stood there resplendent in his dark blue frock coat adorned at the collar and cuffs with gold braid, the living embodiment of the elegance that was the Ritz from his pomaded dark hair down to his highly polished patent leather shoes.

‘Mr Edgar!’ greeted George with a broad smile. ‘Good to see you again!’

‘Good morning, George,’ said Coburg, shaking the man’s hand. ‘This is my Sergeant, Ted Lampson.’

‘Mr Lampson. A pleasure. Any colleague of Mr Edgar’s is very welcome here.’

‘Did our uniformed officer arrive? I phoned the local station to ask them to send someone.’ 14

‘He did indeed. A constable. He’s guarding the door of the suite where the body was found.’

‘Has the doctor been?’

‘He’s upstairs, examining the body. Dr Matthews.’

Thank God for that, thought Coburg. Rob Matthews was very competent and easy to get on with, not like some of his colleagues. Dr Alexander Stewart was one of Coburg’s particular bête noires, an elderly Scot who seemed to have a loathing for all things that weren’t Edinburgh. Coburg had often wondered why Dr Stewart didn’t return to his favourite city if he detested everywhere else so much, but when he’d made discreet enquiries he discovered that the people of Edinburgh, at least the medical authorities, considered Stewart to be an arrogant and bullying pain in the rectum. He’d left the city in high dudgeon in protest at what he considered their insolent attitude towards him and decided to inflict himself on London.

‘In whose suite was the body found?’

‘One of the suites belonging to King Zog of Albania and his party.’

‘One of the suites?’ queried Coburg.

‘The royal family has taken over the whole of the third floor,’ explained George. ‘They are a large party. As well as King Zog and his wife, Queen Géraldine, and their baby son, Prince Leka, there are the King’s six sisters, three nephews and two nieces, along with a twenty-strong retinue of advisers, courtiers and bodyguards.’

‘In whose actual suite was the body found?’

‘One of the courtiers. He isn’t there at the moment, nor, so I’m told, was he there during the incident. It was one of the maids who discovered the body when she went in to 15clean. She found a man who’d had his throat cut lying on the floor, and her screams brought some of the hotel staff.’

‘Does anyone know who the dead man was?’

George shook his head. ‘Everyone claims they have no idea who he is, or what he was doing in the suite. The manager ordered everything to be left as it was until the police arrived. He asked for you particularly.’ Then he added, in low tones: ‘He will be most grateful if the body can be removed as soon as possible. It seems the carpet will need to be replaced, and that needs to be arranged as a matter of urgency.’

‘Thank you, George. We’ll see what we can do to speed things up.’

As Coburg and Lampson headed for the lift, the sergeant grumbled: ‘Replace a carpet! Why don’t they just clean it?’

‘This is the Ritz, Ted. Make do and mend isn’t for them or their clientele. They expect only the best, and they’re prepared to pay for it.’

‘Huh! How the other half live!’ Lampson commented sourly.

The uniformed constable on guard outside the suite saluted as Coburg and Lampson approached, and handed the key to the chief inspector.

‘No one’s tried to come in, sir,’ he told them.

‘Thank you, Constable,’ said Coburg.

They let themselves into the suite, which was the epitome of opulence. The only jarring note to the otherwise perfect decor was the body of a young man, dressed in what appeared to be an elegant dark suit, sprawled on his back on the carpeted floor, one arm flung out. He was of medium height, thin, deathly pale, clean-shaven, his longish dark 16brown hair curling just over his ears. Dr Rob Matthews, a man in his early thirties was kneeling beside the body and looked up at Coburg and Lampson.

‘Bit of a messy one,’ he commented.

The carpet area around the dead man’s neck and shoulders bore a large bloodstain, with more splashes visible all around.

‘That’s quite a spread,’ said Coburg. ‘Must’ve hit an artery.’ He turned to Lampson and asked: ‘Still think it can be easily cleaned?’

‘No,’ Lampson admitted. ‘It’ll always be seen. Maybe next time they’ll put down a carpet that’s better suited. A crimson one.’

Dr Matthews got to his feet. ‘Well, there’s not much more for me to do here,’ he said, putting his equipment into his case. ‘I’ve arranged for him to be taken to University College Hospital, so can I leave you to phone them to send an ambulance for him when you’ve finished?’

‘No problem,’ said Coburg. ‘Time of death?’

‘From the blood clots, the state of rigor, I’d think some time during the early hours of this morning. I’ll know more when I get him to the morgue. Just to let you know, I won’t be starting work on him until later this afternoon. I’ve got a busy schedule of patients to deal with today, living ones who I hope to keep in that condition.’ He headed for the door with a wave of farewell. ‘I’ll leave this one to you.’

Once the doctor had left, Coburg stood examining the scene, particularly the large bloodstain.

‘Four different sets of footprints,’ he said. ‘Two types 17of boots, two of shoes. Assuming one is the doctor’s and the maid didn’t come this far, that means three men were involved.’

He moved nearer to the body, to the side away from the area of blood, knelt down and began to examine the dead man, while Lampson took out a notepad and pencil ready to jot down any salient facts his boss spotted.

‘Age: mid-twenties, is my guess,’ said Coburg. He turned back the lapel of the man’s jacket. ‘Burman’s,’ he said. ‘Theatrical tailors.’ He looked at the man’s shoes. ‘The shoes don’t match the suit. That’s smart and cut to perfection. His shoes are clean, but look at the soles. They’ve been re-soled and look like it needs to be done again.’

‘So, dressed up to look like money, but piss-poor.’

Coburg went through the man’s pockets looking for a wallet or some form of identification.

‘Nothing to show who he was.’

‘Reckon someone took his wallet? A robbery?’

‘Judging by the fact his shoes needed repairing, I doubt if there was much money in it. No, it was taken to stop us finding out who he is.’ He bent down and studied the man’s face, gently running a fingertip around his ears and eyes before putting his finger to his nose.

‘Traces of make-up around his eyes and ears.’

‘An actor of some kind?’ suggested Lampson. ‘That would fit with the suit being from a theatrical tailor.’

‘Possibly,’ said Coburg. ‘Or it could have something to do with the Pink Sink.’

‘What’s the Pink Sink?’ asked Lampson.

‘It’s a club for homosexuals in the Ritz’s basement,’ said Coburg. 18

Lampson looked discomfited. ‘And the hotel allows it?’ he asked, indignantly. ‘It’s against the law!’

‘The activity may be illegal, but it’s a private club on private premises.’

‘So?’ demanded Lampson. ‘Two clubs in Soho were shut down last month for that sort of thing.’

‘True, but I expect those two clubs didn’t have the same kind of influential people among their clientele,’ said Coburg. ‘The Pink Sink is the haunt of some very high-ranking military types, not to mention MPs and top civil servants, as well as lesser ranks and waiters and such.’

‘Disgusting!’ snorted Lampson. ‘They ought to arrest ’em all.’

‘If they did that, half the military top brass and a quarter of the Cabinet would be in jail,’ said Coburg.

‘How come you know so much about it?’ asked Lampson suspiciously.

‘Before the war, I had friends for whom the Ritz was their home from home. Not the Pink Sink, rather the Palm Court and the Rivoli bar, which is where the straights gather, but I learnt what went on. You never know when it might come in useful.’

Lampson nodded. ‘Like now. So d’you reckon this dead bloke was one?’

‘It’s possible,’ said Coburg. ‘But if so, the question is, what was he doing in one of the Albanian royal family’s suites?’

‘He could be Albanian,’ said Lampson.

‘He could indeed. We’ll get a photograph of him and pass it around the King’s retinue, see if anyone recognises him. In the meantime, let’s go and have a word with George.’ 19

‘The hall porter?’ asked Lampson. ‘What will he know?’

‘Everything,’ said Coburg with a smile. ‘He’s much more than just your regular hall porter. He’s been here as long as I’ve been coming here. He’s known affectionately as George of the Ritz across four continents. He’s trusted by everyone, the guests as well as the hotel management. Royalty, millionaire businessmen, politicians – they all know and trust him. And there’s nothing that goes on in this hotel he isn’t aware of.’

Returning to the lobby, Coburg telephoned Scotland Yard asking for a photographer to be sent to take some photos of the dead man. ‘And as soon as you can,’ urged Coburg. ‘Send Duncan Rudd if he’s free.’ He replaced the receiver and turned to the hall porter.

‘Once we get some pictures of him we’ll be able to move the body and return your hotel to you, George,’ Coburg told him. ‘As soon as the photographer arrives, can you put a call through to University College Hospital and ask them to send an ambulance to pick up the body? Quote Dr Matthews’ name. They’ll know the drill.’

‘Will do,’ said George.

‘Thank you,’ said Coburg. ‘One last thing. What can you tell us about King Zog and his retinue?’

George shot a wary and inquisitive look towards Lampson, to which Coburg said: ‘I assure you, George, Ted is the perfect image of confidentiality. I’d trust him with my life.’

Reassured, George nodded, then told them: ‘As you probably know, King Zog is the dethroned King of Albania. He and his family fled their home country last 20year in the spring just a day before Mussolini’s troops invaded. They’ve journeyed throughout Europe and ended up in Paris, managing to escape to London just before the Germans invaded. I believe they were helped to flee by a British Intelligence officer, Commander Fleming.’

‘Ian Fleming?’

George nodded. ‘They learnt that Mussolini’s troops were about to invade their country. But the risk to them wasn’t just from the Italians. King Zog had been the target of assassination attempts on many occasions.’

‘Who by?’

‘The political opposition in Albania. Also a group calling itself the Bashkimi Kombëtar, anti-Zog activists living in Austria. There was one attempt in which Zog was shot twice, but survived.’

‘Amazing!’ muttered Lampson.

‘And now? I note he’s got quite a large number of bodyguards with him here.’

‘He has, but he’s also able to take care of himself. I hear that he killed some of those who plotted against his life.’

‘You mean he had his bodyguards kill them?’ pressed Coburg.

‘In some cases, but I believe he took care of some of his would-be killers personally.’

‘He sounds like a dangerous man.’

‘Not really, just a man defending himself.’

‘So long as he doesn’t try it in this country,’ said Coburg.

George then leant forward and added in a conspiratorial tone: ‘The most interesting aspect is it’s said that he brought two million in gold bullion and American dollars with him, reportedly taken from the Albanian National 21Bank. It’s kept in strong boxes in his suite, and every now and then the King’s sister takes some to a bank and changes it into sterling.’

‘Two million,’ said Coburg. ‘There’s a motive for murder. It would help if I looked at your guest list, just in case any known names leap out.’

‘Of course,’ said George. ‘I expected that and made a copy for you.’

He took some handwritten pages from his desk and handed them to Coburg, who ran his eye quickly over them.

‘It looks as if you’re full,’ he commented. ‘Every room and suite occupied, so the war doesn’t seem to be affecting you.’

George shook his head sadly. ‘Not as far as clients arriving, but it’s a disaster from a staff point of view. It was bad enough when all our German and Austrian staff were arrested and taken away, but now, since Mussolini declared war on England, all our Italian staff have been interned as well. Waiters, chefs, so many Italians worked here. And the irony is that most of them are anti-fascists who fled Italy to escape from Mussolini and his thugs. Just like so many of the Germans we employed were refugees from the Nazis. And now they’re all locked up in prison camps.’

‘Hopefully the authorities will get that sorted out soon,’ said Coburg.

‘If there’s any chance of you having word …’ said George.

‘I doubt if the powers that be will listen to me,’ said Coburg. ‘I’m just a lowly policeman.’

‘A detective chief inspector, with some important connections,’ murmured George, appeal in his voice. 22

Coburg smiled. ‘Not as important as many wish. But I’ll certainly mention it to one or two people who might be able to push things along.’

‘Thank you.’

CHAPTER THREE

As they made their way back up to the third floor in the lift, Lampson ventured his view: ‘I reckon you hit the nail on the head, guv. The murder is connected with the money this King Zog’s got stashed. I know people who’d kill someone for a fiver, so the chance of a pop at two million – it’s got to be the motive.’

‘The question is: was this man killed trying to steal it or trying to stop it being stolen?’ mused Coburg.

‘Trying to nick it,’ said Lampson firmly. ‘If he got done by the thieves he’d be part of the King’s crowd, so someone would know who he is.’ He gave a thoughtful frown. ‘Unless they’re lying. Covering up.’

‘Yes, I wondered that,’ said Coburg. ‘In Eastern Europe things are often handled with discretion to avoid scandal.’

‘Leaving a dead body lying around doesn’t show much discretion,’ commented Lampson. 24

‘Perhaps they went out to make arrangements to dispose of the body when the maid stumbled upon him and raised the alarm.’

‘It’s all a bit iffy, guv,’ said Lampson doubtfully.

‘Yes, it is,’ agreed Coburg.

The lift stopped, and they returned to the door of the suite and the waiting constable.

‘A photographer’s on his way, Constable,’ Coburg informed him. ‘Once he’s done his work the body will be removed and then you’ll be free to return to your duties.’

‘Thank you, sir. My sergeant will be relieved about that. We’re short-handed today.’

‘The war makes demands on us all,’ commented Coburg sagely.

Back inside the suite, Lampson looked again at the blood and commented: ‘One thing’s for sure, he was definitely killed here, not somewhere else and then dumped in this suite.’

‘But are the King and his retinue involved?’ mused Coburg. ‘Or is it nothing to do with them at all?’

Out of the blue, Lampson asked: ‘Who’s this bloke Ian Fleming? When that George said to you about him, it struck me you knew him.’

‘In a way,’ said Coburg. ‘We were at the same school, Eton, but not at the same time. He’s nine years younger than me. But our paths crossed infrequently at social functions from time to time.’

‘What’s he like? George said he helped smuggle the King and his mob out of France, and while the Germans were there. He must have guts.’

Coburg nodded. ‘Oh yes, he’s got guts all right.’ 25

‘You don’t sound like you like him much,’ said Lampson.

‘Oh, I do. He’s very likeable, in an arrogant way. I just think he’s dangerous. He takes risks.’

‘It’s war. People take risks in war. You did in the last one, guv, from what I’ve heard.’ He paused, then added carefully, watching his inspector the whole time to check that he wasn’t overstepping the mark: ‘They say you got shot nearly to bits while leading a charge against a German machine-gun post just a week before the Armistice.’

‘Hardly shot to bits, Ted. And I survived. Many didn’t. And that wasn’t so much taking a risk as following orders. There was a job to be done. Fleming takes risks just for the hell of it.’

‘But he got the King and everyone else out.’

‘Yes, that can’t be denied,’ said Coburg. ‘If I see him again, I’ll compliment him.’

There was a knock on the door. Lampson opened it and Duncan Rudd entered, carrying a large camera. He grinned at the detectives.

‘Here we are again, Chief Inspector. Another dead body.’ He looked down at the spread-eagled man with a frown of disapproval. ‘Someone’s made a right mess of that carpet!’

‘They have indeed, Duncan,’ said Coburg. ‘I’m glad you were available. Well, I think the sergeant and I have seen enough. Can you get me the photos as soon as you can? An ambulance should be on its way from UCH to remove the corpse, but if they arrive before you’re finished, don’t let them rush you. You know what some of these ambulance crews can be like, all urgency and speed. In this case, there’s no need for it. He’s dead.’ 26

‘Trust me, I’ll make sure I get some good pictures,’ Rudd assured him.

Coburg nodded, then he and Lampson left the photographer to his work, with Coburg giving the constable a last word. ‘You’ve done a good job today,’ he complimented him. ‘You can tell your sergeant I said so.’

As they left the Ritz and headed for where they’d parked the Bentley, Coburg asked casually: ‘D’you fancy taking the wheel back to the Yard, Ted? Give the old girl a spin.’

Lampson’s face lit up with delight, as Coburg expected it would. Lampson was a demon with cars, having been a trainee mechanic before he joined the police, and Coburg knew he would love a car of his own, but his wages as a detective sergeant didn’t extend to it. Coburg was only able to get away with driving the Bentley because he’d managed to persuade the top brass at Scotland Yard to designate it as an official police car, but he knew that couldn’t last for much longer. Questions were already being asked, and jealous frowns directed at him whenever he pulled up at Scotland Yard in it.

‘Thanks, guv.’ Lampson smiled as he slid behind the steering wheel and started the engine. Coburg made himself comfortable on the passenger seat.

‘Take the opportunity while it lasts,’ said Coburg. ‘I calculate another week if we’re lucky and then the old dear will have to go into a garage for the duration, and we’ll be driving around in an official police car.’

‘Killjoys,’ grumbled Lampson. ‘It’ll be a dreadful waste to have this beauty sitting idle in a garage.’

‘Rules are rules, Ted,’ said Lampson. ‘And we of all people have to be seen to keep them. We’ve had a good run for our money.’ 27

Coburg loved driving the car, especially as petrol rationing had driven most private cars off the road, making London virtually a traffic-free zone except for official vehicles, but his decision to let Lampson drive them back to Scotland Yard wasn’t entirely altruistic. His sergeant’s mention of the injuries he’d received right at the end of the First World War had brought the whole thing back to him and he was worried that those memories might impede his driving. At times, when he did think about it, too often he drifted off and was back there again, twenty-two years ago at the Sambre–Oise canal.

When he thought about it now, it was ludicrous. Nineteen years old and a captain in the army, by virtue of the Officers Training Corps at Eton. Giving orders to men in their twenties and thirties, any one of whom had more experience of the war than him, who’d only been in France since January 1918. But he’d done his part, luckily only suffering minor injuries, until that final battle of the Sambre–Oise Canal. 4th November 1918. One week before the Armistice and the end of the war. They’d been told they had the enemy on the run, and that may well have been the case, but at Sambre–Oise the Germans had put up a fierce resistance as they fought to prevent the Allies getting to the canal, let alone across it. For years afterwards he’d often wake at night, drenched in sweat as he relived that attack.

It had been Coburg who’d blown his whistle to signal the assault at dawn, before being the first to ascend the wooden ladder out of the deep, muddy trench where they’d spent the night. Ahead of them was the German defensive line on the other side of the canal, their target, but first they had to cross open fields to get there. 28

Tacka-tacka-tacka-tacka! The German machine guns opened fire and bullets tore into Coburg’s unit. Some of the men either side of him stumbled and fell, but he kept going, urging the others on, ducking low, weaving from side to side, firing all the time. Bullets thudded into the earth at his feet, others sailing past him, so close that one tore at the sleeve of his uniform.

Coburg fired back and kept running. The canal was in sight now and he made for the lock, but the Germans had put a machine gun inside the lockhouse and the rapid machine-gun fire was tearing into their advance, more soldiers falling the nearer they got to the canal. He needed to put that machine gun out of action.

He dropped down to the ground, laying flat, using what he could as cover, a small bush, before getting to his feet and running, zigzagging, firing the whole time. Around him men were collapsing, chunks of flesh coming off them, spattering blood, and suddenly there was a crash against his chest and he felt as if he’d been ripped open. He fell, sinking down, and his last thought was: This is how I die …

He was told he was in the medical tent for two days, with the expectation that he wouldn’t make it. But he did, coming round to a smell of blood and vomit and disinfectant and screams of pain.

‘You were lucky,’ said the doctor who examined him. ‘The bullets hit you on the right side of your chest, taking out the lung. If you’d been hit on the left side you’d be dead, heart riddled like a colander. But that’s the wonder of the human body. We’ve got two of lots of different organs and at a pinch we can survive with just one. But the heart 29and brain, they’re different. Only one of each, and get a bullet through that and it’s almost certain goodbye.’

And so he’d lost a lung, which was why he’d been turned down for active service this time around. ‘You’re forty years old with one lung. You can’t be risked. You’re worth more doing what you do here in Blighty, keeping law and order on the Home Front. That’s vital to the war effort.’

Twenty-two years ago, and sometimes it seemed like it was only yesterday. The war to end war, they’d called it. It was estimated that at least eighteen million soldiers had died, and they said that such a catastrophically high death rate – a whole generation virtually wiped out – would ensure such a war would never happen again. Yet here they were again, and against the same enemy: Germany.

On their return to Scotland Yard, Coburg delegated Lampson to go to the office they shared to check for any messages, while he reported on the events of the morning to his immediate superior, Superintendent Allison. Like Coburg, Edward Allison had served in the First World War, in his case surviving the carnage of Gallipoli. Half a million Allied troops fighting against half a million Turkish, with each side suffering huge casualties before the bloody conclusion and the evacuation of the defeated and weary Allied forces from the beaches of the peninsula. As briefly as he could, Coburg related the salient details of the hotel murder to the superintendent: the anonymous dead man in the King’s suite and the rumours of the valuables kept there. 30

‘Two million in gold bullion and cash,’ said Allison. ‘A motive for murder.’

‘Indeed,’ said Coburg. ‘And I agree it seems the most likely. But there are other things going on at the Ritz at this moment, any of which could result in someone being killed. For one thing, there’s a cocktail bar in the Ritz’s basement, known as the Pink Sink. It’s where politicians and senior civil servants make homosexual assignations with military personnel, as well as some of the hotel staff. So, the threat of blackmail is a possibility. And blackmailers also often end up dead.’

‘And there’s no clue as to the dead man’s identity, or why he was found in the King’s suite?’ asked Allison.

‘I’m afraid not,’ said Coburg.

Allison frowned. ‘I suspect this may be one of those cases where we spend an awful lot of time on it and come up with nothing,’ he said. ‘Particularly as it involves the King of Albania, who I understand to be a very private person and I assume will not like too many questions asked, especially if these reports about the fortune hidden in his rooms are true. There is also the likelihood that the Foreign Office will be involved, not to mention MI5. Plus, the business about this Pink Sink establishment. This could get very messy, Coburg. Political intrigue can be very dangerous, especially when there’s a war on.’

‘Yes, sir. What do you suggest our course of action should be?’

‘We have a dead man and no one knows who he is. No one’s reported him missing. He could well be an alien. By all accounts King Zog’s retinue are keen for the matter to be closed.’ 31

‘So, you think we should call the case closed?’

‘No, no, just … put it to one side. Perhaps things will turn up.’

Coburg was just about to leave the office and return to catch up with Lampson when Allison stopped him.

‘There’s, ah … one more thing, Chief Inspector,’ said the superintendent, and the hesitancy of his tone gave Coburg a warning that something unpleasant was about to follow.

‘Sir?’ he asked, doing his best to stop his apprehension from showing. What was it? Bad news, for sure. Had something happened to his brother, Charles, in the POW camp? Had he attempted to escape? It would be the sort of thing he’d try and get himself killed doing it.

‘Your Bentley,’ said Allison awkwardly.

‘Sir?’ queried Coburg again.

‘There have been questions,’ said Allison, unable to look Coburg in the eye. ‘In the House. Apparently there was an article about you in the Daily Worker. I don’t know if you saw it?’

‘No, sir. I rarely have time to read the papers and so far I haven’t included the Daily Worker.’

‘The article doesn’t name you, but it mentions a high-born aristocrat working as a chief inspector in the police force who’s allowed to drive his own luxury Bentley around while ordinary people are barred from running a private car.’

‘It was agreed my car would serve as a police vehicle, sir, thereby freeing up police cars for use.’

‘Yes, that was the agreement, but it seems the assistant commissioner was hauled before a committee of MPs and 32grilled about the matter as a result of one of them seeing the article.’

‘I understand, sir. The Bentley goes into a garage and stays under wraps.’ Then Coburg asked: ‘Out of curiosity, sir, do you happen to know which particular MP raised the issue with the AC?’

‘If you’re thinking that it was the result of the article in the Daily Worker, it must have been a Labour MP, then I can assure you that wasn’t the case.’ he hesitated, then said: ‘I believe it was the Right Honourable Wister Gormley.’

Yes, thought Coburg. Gormley, who’d smashed his own cars up, the Rolls and the Bentley, both times while drunk, and who’d appealed to Coburg to take care of the charge of dangerous driving, saying, ‘After all, we were at school together.’ Coburg had refused, insisting the law applied to everyone. So this was Gormley’s revenge. Which was hardly a surprise. Wister Gormley had been a rat when they were at school, and he was still a rat.

‘Thank you, sir. You can tell the AC I’ll have the Bentley garaged and arrange for a car from the pool for myself and Sergeant Lampson.’

Lampson’s reaction when he told him about the Bentley was exactly as Coburg had thought it would be: sour and bitter.

‘Things are in short supply, Ted,’ Coburg reminded him. ‘That’s why we’ve got rationing. And petrol for private cars was the first thing to go.’

‘Some people get away with it,’ he grumbled. ‘Look at those rich types motoring around in Daimlers and I don’t know what.’ 33

‘Official business, I expect,’ sighed Coburg.

‘Official business, my arse!’ snorted Lampson. ‘Everyone’s got a ration book with a limit on how much they can buy. Half a pound of bacon a week, a pound of sugar, a shilling’s worth of meat, half a pound of butter, if you can afford it. Me and Terry use margarine instead. All right it don’t taste as good, they say it’s made from whale oil, and it’s true it’s got a bit of a fishy taste, but we can get twelve ounces for a coupon instead of only half a pound of butter.’ He snorted angrily. ‘But I bet you them MPs and lords and ladies don’t have the same restrictions!’ Then he looked at Coburg and added awkwardly: ‘Begging your pardon, guv, I didn’t mean you when I talked about lords and ladies.’

‘I am not a lord, Ted. My brother is a duke, but that’s because our father was, and I assure you I have a ration book the same as everyone else. And I stick to it.’

‘You may, but I bet not all the top nobs do. They keep their good cars.’

‘I expect you’re right,’ agreed Coburg, used to his sergeant venting his feelings about the unfairness of society. ‘But the bottom line is the Bentley goes in the garage. I’ll let you select the best car from the pool, otherwise we’ll be scrabbling for the leftovers every time we need a car and end up with the one with flat tyres and a dodgy gear box. I’ll sign the requisition. If you like, you can keep it at your place, if you don’t mind picking me up in the mornings.’

Lampson shook his head. ‘Not a good idea, guv. Somers Town is all right for me, but I wouldn’t park a car there. Not overnight. Not even a police car.’ 34

‘Yes, I take your point. All right. Sort one out and once it’s here we’ll do a two-car run and put the Bentley in dock. By the way, it looks as if the dead man at the Ritz is going to be put on the backburner. The super thinks the fact we don’t know who he is and royalty and the intelligence services might be involved could be a complication we don’t need. He also thinks there’s not a lot of chance of us solving the case.’

‘That’s not much of a vote of confidence,’ grunted Lampson.

‘No, but with a war on, I’m sure there’ll be plenty to keep us busy.’

The phone rang, and Lampson picked it up. ‘Detective Chief Inspector Coburg’s office.’ A frown passed across his face, then he said: ‘Yes, sir. He’s here. One moment and I’ll put you on to him.’

He put his hand over the receiver and whispered to Coburg: ‘It’s the secretary to King Zog. A Count Ahmed. He has a message from the King.’

Coburg took the phone. ‘Detective Chief Inspector Coburg speaking.’

‘Chief Inspector, this is Count Idjbil Ahmed, private secretary to His Majesty, King Zog of Albania. We understand that you were at the Ritz today investigating the dead man found in one of the suites.’

‘Yes, Count Ahmed, that is correct,’ said Coburg, wondering where all this was leading.

‘His Royal Majesty, King Zog, would like to invite you to meet him to discuss the situation. Would one-thirty be convenient?’

Coburg looked at the clock, which showed twelve-thirty. 35

‘One-thirty will be excellent,’ he said. ‘Tell His Majesty I look forward to meeting him.’

He hung up the phone and grinned at Lampson.

‘I think we might be back on the case.’

CHAPTER FOUR

King Zog sat in a high-backed armchair so ornately decorated that Coburg wondered if the Ritz had managed to find a replica of the Albanian throne for their royal guest. One of the King’s bodyguards stood just behind the gilded chair and slightly to one side, his grim face fixed on Coburg. Another bodyguard stood by the door to the suite, one hand poised over the inside of his bulky jacket, where Coburg assumed he kept a pistol.

The King was tall and slim with a pencil-thin moustache, giving the impression of a matinee film idol, made more so by the elegant way he smoked his cigarette. He regarded Coburg guardedly, obviously curious about this detective chief inspector.

‘I am told that you are a member of the British royal family,’ said Zog.

Coburg weighed up how to answer. The suggestion that he 37might be connected to the House of Windsor was obviously the reason the King had invited him, royal to royal. Even though Coburg had learnt from a discreet phone call that, for all the regal trappings, Zog was a self-proclaimed king, having declared himself the first monarch of Albania after the country’s independence from the Ottoman Empire. But being royal, and associating with other royals, was obviously of great importance to him. Aware of that, Coburg was sure that to contradict Zog could result in a curt dismissal, and Coburg was curious to find out more from the King that might lead to information about the dead man.

‘Distantly related,’ he said.

‘And yet you work as a policeman.’

‘I’m the third son,’ explained Coburg. ‘My eldest brother, Magnus, inherited the family title and estates when our father died.’

‘You have the same name as the British royal family before they changed their name to Windsor during the last war. Saxe-Coburg.’

‘They were Saxe-Coburg-Gotha,’ said Coburg politely. ‘As I say, related, but at the same time, distant.’

‘You are a third son,’ mused Zog. ‘Your other brother?’

‘Charles. He was taken prisoner at Dunkirk and is currently in a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany.’

‘The war, it has made exiles of us all,’ said Zog. He looked directly at Coburg. ‘Have you ascertained any information about the dead man who was found in our rooms?’

‘Not yet, Your Majesty,’ said Coburg. ‘We are still investigating.’

‘I wish to know who he was, and why he was here,’ said Zog. ‘I have many enemies and need to discover if his 38presence indicates a plot against me here in England. Not so much for me, but I’m concerned for the safety of my family. My infant son, Leka. Queen Géraldine. My sisters, who are very dear to me.’

‘Of course, Your Majesty,’ said Coburg. ‘I wonder if you could tell me who occupies the suite where the dead man was found?’

‘Why?’ asked the King warily.

‘In order to get to the bottom of what happened,’ replied Coburg. ‘You ask me to find out who the dead man was. It would help me find the answer to that if I could discover why he was in that particular suite.’

‘My personal secretary, Count Ahmed.’

‘The person who telephoned to invite me here. Then at least we have been introduced. Could I talk to the Count?’

‘He is not here at the moment,’ said Zog. ‘He is … away. I will get him to telephone you when he returns.’

Zog stood up. So, our audience is at an end, thought Coburg. He also rose to his feet.

‘Thank you, Your Majesty,’ he said. ‘I look forward to talking to Count Ahmed.’

Ted Lampson sat at his desk in Coburg’s office and studied the notes he’d made about the case. Not that there was much to put down on paper. Dead man, unknown, throat cut. Possible motive: two million in gold bullion and foreign notes. It was a queer one and no mistake. Whatever had happened, none of the money or gold had been taken. At least, as far as they knew. Maybe that was what this King Zog wanted to talk to the guv’nor about. Maybe someone had nicked it, or part of it, but the King wanted that kept 39secret. Nothing was straightforward when royalty was involved, and Lampson had learnt that from earlier cases, when the guv’nor and he had investigated some goings on at Buckingham Palace. They’d asked for Coburg in particular, the same as they’d done at the Ritz. ‘It’s cos of his royal connections,’ one of his mates in the uniformed division had told him. ‘Saxe-Coburg. He’s one of their own.’

But the guv’nor never came across as being different. There were no airs and graces about him. Yes, he talked posh, but then he came from a posh family and he’d been to a posh school. The poshest. But he didn’t lord it over people. He treated everyone the same. That was one of the reasons why Lampson liked working with him. He was straight as a die, honest and fair. You couldn’t ask more from a boss. Like this business of the car. Offering Lampson the chance to keep it at his place. He couldn’t think of another boss who’d do that. Not that Lampson would. As he’d said to Coburg, that’d be asking for trouble. Any car left on the street overnight in Somers Town, by morning the wheels would be gone and anything else that could be lifted. The only cars that were left untouched were those belonging to the local gangsters.

Anyway, Lampson had selected a good one from the pool, and to make sure no one else took it, he’d written a note in large letters – Reserved for Chief Inspector Coburg – and left it on the windscreen. It wouldn’t be the same as the Bentley, but he felt sure the guv’nor would be fine with it.

Lampson often dreaded the thought that one day Coburg might leave and he’d be assigned to one of the complete tossers in the building. The ones who acted as if they were special, even though they weren’t. 40

If that happened, I’d leave, Lampson told himself determinedly. I’d rather go back to being on the beat in uniform.

There was a knock at the door. At Lampson’s call of ‘Come in!’, Duncan Rudd entered bearing a large manila envelope.

‘The photos,’ he said. ‘I’ve just printed three for you at the moment. Paper’s in short supply. How many will you want?’

‘Three’ll do for now,’ said Lampson. ‘The guv’nor’s seeing the King at the moment. We’ll know if we need more when he gets back.’

‘The King?’ said Rudd, impressed. ‘Where? Buckingham Palace?’

‘Not our king,’ snorted Lampson. ‘The one at the Ritz where the dead body was found. King Zog.’

‘King Zog,’ said Rudd with a smile. ‘Sounds like someone from the comic books. Like Ming the Merciless in Flash Gordon.’

CHAPTER FIVE

Coburg had just left the lift and was heading across the reception area towards the swing doors of the Ritz entrance, when a woman’s voice called out brightly: ‘Edgar!’

Coburg stopped and turned, smiling at the sound of a voice he recognised. A young woman in her late twenties, petite, blonde and very beautiful, was coming towards him. Rosa Weeks: jazz pianist and singer with a list of riotous anecdotes, all of which would hold an audience enthralled. And not just an audience, reflected Coburg, as she held her face up for a kiss.

A full kiss or a peck on the cheek? wondered Coburg. It had been a long time since they’d last been together and he didn’t want her to think he was so arrogant to claim ownership of her. Rosa dealt with that by kissing him firmly on the lips, then leant back in his arms and smiled up at him.

Coburg beamed happily. ‘Rosa! It must be …’ 42

‘A long time.’ Rosa smiled. ‘You never called.’

‘I did, but the message I got was you were away on tour. Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam.’

‘Yes, although those hot spots have rather dried up for me lately. So, what are you doing here? A guest or the day job?’

‘Official. We’re looking into an incident.’

‘The dead guy in one of King Zog’s suites?’

‘You know about it?’

‘Baby, everybody knows about it.’

‘So, you’re staying here?’

She shook her head. ‘Too rich for me. No, I’m doing a cabaret spot here in the Rivoli Bar.’

‘Which night?’

‘Every night for the next two weeks. Which is why I’m here, checking that no one’s run off with the piano.’

Coburg chuckled. ‘Now that would be some heist to pull off.’

‘You’d be surprised some of the things that disappear. I hear that four guys turned up at the Detour Club in Wardour Street and said they’d been asked to take the piano away for restringing. And, believe it or not, they were allowed to carry it out of the place.’

‘Never to be seen again?’

‘You got it.’ Then her face clouded and, worried, she asked him in a lowered voice: ‘How long do you think we have before the Germans invade?’

‘Why would I know?’ asked Coburg.

‘Because you were a soldier. You know how things are.’

‘No one knows,’ said Coburg. ‘There are lots of rumours going around …’

‘You’re telling me,’ she said. 43

‘But at the moment the RAF are keeping the Luftwaffe at bay. And while that’s happening the Germans won’t invade.’

‘There’s talk the RAF won’t be able to hold them off for much longer. Every day I expect bombs to rain down on us. You can see their planes even from London.’