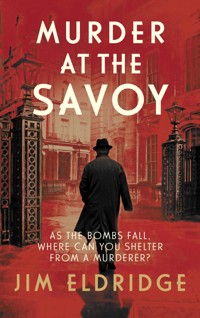

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hotel Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Jim Eldridge, author of the Museum Mysteries, turns his pen to Wartime London's grandest hotels. September 1940: the height of the Blitz. The Savoy Hotel boasts London's strongest air raid shelter with all the luxury expected from one of the capital's most prestigious hotels. It prompts the arrival of a disgruntled crowd from the East End, demanding they be allowed entry and respite from the endless bombing raids. They are given permission to enter and are stunned by the opulence that greets them. The all-clear sounds the next morning and London comes slowly back to life, but not everyone can dust themselves down and carry on. One of the hotel's guests has been discovered dead, stabbed in the back. Detective Chief Inspector Coburg and Sergeant Lampson are called in and the finger of suspicion falls firmly upon the East Londoners, but not everything is as it seems in these sumptuous surroundings.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 421

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

MURDER AT THE SAVOY

JIM ELDRIDGE

For Lynne, and she knows why

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Saturday 14th September 1940, London

The wail of air raid sirens filled the air. On the pavement outside the Savoy hotel an angry crowd of about fifty people shouted, demanding to be let in, but found their way barred by the giant figure of the doorman, Lund Hansen, resplendent in his uniform of deep blue, his long overcoat decorated with brass buttons that shone even in the blackout.

‘Let us in!’ shouted a small pugnacious man who seemed to be the crowd’s self-appointed leader. He waved his arms towards the people behind him. ‘Look at us! We are the poor!’

Hansen looked. There were men, most of them shabbily dressed, many women, some of whom looked to be pregnant, and children.

‘We are dying!’ shouted the man. ‘We have nowhere to be safe. While you and that lot in there—’ and he jabbed his index finger angrily towards the doors of the Savoy ‘stay safe deep underground, on beds with silk sheets and with the best food and wines!’ And he produced a page torn from a newspaper, an advert extolling the virtues of the air raid shelter deep beneath the Savoy. ‘That’s what it says here! But we don’t need beds with silk sheets. All we ask is the decent right to safety, because we don’t have any shelters in Stepney, just surface shelters. All they do is maybe stop shrapnel tearing you to bits, but they won’t protect you if a bomb comes down on top of it, or too near. Eight days we’ve suffered this, night after night. There’s thousands of us dying in the East End while your lot hide in this expensive hole in the ground under this hotel. Well, we want some of that safety. We deserve it! Aren’t we human beings, too, the same as them? Or aren’t we worth as much because we’re poor?’

‘Let us in!’ some of the crowd shouted, and soon other voices joined in so that it became a chant. ‘Let us in! Let us in!’

At the back of the crowd the two police constables who’d been on duty outside the Savoy when the protestors had arrived had now been joined by more uniformed police, some of whom had drawn their truncheons, obviously intending to disperse the protestors by force if necessary.

The door of the Savoy opened and a tall man immaculately dressed in a frock coat, striped trousers and gleaming white shirt and black tie stepped out, and surveyed the crowd with an imperious gaze under which the crowd fell silent, as the majority of people did when confronted with the hard penetrating stare of Willy Hofflin, the Savoy’s assistant manager. Hofflin turned to the doorman.

‘What is occurring here, Mr Hansen?’ he demanded in his clipped Swiss accent.

It was the small man who spoke up, having recovered his voice.

‘We are the poor!’ he said. ‘We’ve come all the way from Stepney in the East End because we have no shelter to hide in when the bombs come down on us. They won’t let us into the Tube stations, where we’d be safe. There’s nowhere but surface shelters, which fall down when they’re hit by bombs and kill everyone in them. It’s been this way for eight days and nights.’ Once again he waved the advertisement from the newspaper, this time at the assistant manager. ‘Yet you boast of having the strongest underground shelter in London here at the Savoy, with every luxury. We only want one luxury – to stay alive when the bombs fall. And that shouldn’t be a luxury! It should be the right of everyone to be able to get shelter, not just the rich.’

And the small man glared at the tall Swiss, challengingly. Hofflin returned his stare, then nodded and turned to the doorman. ‘There is no reason why these people should not have the same shelter as the Savoy’s guests. Let them in.’

With that, he stepped to one side. Lund Hansen pulled open the main entrance door.

At first, the crowd stared, bewildered; this was not what they had expected. Then suddenly a cheer went up, starting at the back of the crowd and echoing around the rest, and the small man stepped forward, leading the way for his comrades into the pristine, luxurious Savoy hotel.

In Hampstead, the corrugated iron Anderson shelter half-buried in the garden of the small block of flats shuddered but held solid as the bombs fell.

Seven people were crammed into the shelter: Detective Chief Inspector Coburg and his wife, Rosa, Eric and Norma Henderson, Peter and Dorothy Watts, and widower Walter Marsden.

Those bombs were a bit too close, thought Coburg, pulling Rosa close to him in a hug he hoped was reassuring. She nestled into his shoulder.

‘It’ll be fine,’ she whispered. ‘The thick layer of earth on top of this thing is doing its job.’

Who’s reassuring who, thought Coburg. That was one of the things he loved about Rosa, her apparent fearlessness. Not that she didn’t get scared. She’d told him that when she first began appearing in public as a singer she sometimes used to vomit in her dressing room as the result of nerves, before composing herself and walking out to her piano and the waiting audience. Even here in this tiny, cramped air raid shelter, seven days into the Blitz, as the intensive bombing night after night by the Germans was being called, she hid whatever fear she may have felt, doing her best to appear calm.

DCI Coburg – or, to give him his full title, the Hon. Edgar Walter Septimus Saxe-Coburg – and Rosa Weeks, the celebrated jazz singer, had been married just two weeks before at Hampstead Registry Office. A very simple ceremony, no families in attendance, just Coburg’s detective sergeant Ted Lampson, as his best man, and Maisie Oxley, a fellow musician friend of Rosa’s who played saxophone in Ivy Benson’s all-girl big band witnessing for Rosa. Rosa’s family were in Edinburgh and both Edgar and Rosa felt it was too dangerous for them to travel to London while the bombing continued, especially as the main railway lines seemed to be a major target for the Luftwaffe, and Edgar had decided against involving his elder brother, Magnus, the Earl of Dawlish, because he was sure that Magnus would insist on the wedding being held at the family’s ancestral home, Dawlish Hall, and that would only lead to rows as Edgar and Rosa both wanted a quiet occasion.

The Anderson shelter shook again as another bomb struck nearby and there was the sound of rubble crashing down on the protective earth covering of the corrugated iron roof, causing the occupants of the shelter to exchange nervous looks.

‘They should open the Tube stations as shelters,’ scowled Eric Henderson. ‘We’ve got the deepest in the whole system here at Hampstead station. What is it? Two hundred and fifty feet deep?’

‘One hundred and ninety-two feet,’ said Walter Marsden quietly, adding an apologetic smile to take the edge off correcting his neighbour. ‘I work for London Underground,’ he explained.

‘Then why don’t you get them to open the stations during air raids?’ demanded Henderson.

‘It’s not my decision,’ said Marsden. ‘That’s down to the Government, and I get the impression they’re worried that if they do, the whole mass of London will disappear down them and remain there.’

‘Nonsense!’ snorted Henderson.

‘Eric’s right,’ said Norma Henderson, backing her husband up as she usually did. ‘It’s all right for those in Government; they’ve got all those places all along Whitehall they can hide in.’

‘I’ve been told that Winston still goes to his country home in Kent, Chartwell, and sits on his roof watching when there’s an air raid,’ put in Dorothy Watts.

‘That’s because the Germans aren’t bombing Chartwell!’ Henderson snorted. ‘He knows he’s safe there.’

‘I hardly think so,’ said Peter Watts thoughtfully. ‘After all, Chartwell’s not far from Biggin Hill, and that whole area is still taking a battering.’

The shelterers fell into thoughtful silence at this reminder of the Battle of Britain that was still taking place. The airfields of Kent and Sussex being bombed during the day; London and the other major cities bombed at night.

‘What do you think, Mr Coburg?’ asked Dorothy Watts. ‘What’s the word from inside Scotland Yard? What can we expect?’

‘I’m afraid I’m the wrong person to ask, Mrs Watts,’ replied Coburg ruefully. ‘I’m just a humble detective inspector.’

‘Humble?’ scoffed Henderson. ‘Don’t you have a brother who’s high up in the War Office or something? Lord Whatsisname?’

‘My brother Magnus is the Earl of Dawlish, but he doesn’t work for the Government,’ said Coburg. ‘It was my other brother, Charles, who used to work for the War Office but he re-enlisted in the army when war broke out. He was taken prisoner at Dunkirk and is currently in a German prisoner-of-war camp.’

‘How awful for you,’ Dorothy Watts shuddered.

‘Rather worse for Charles, I feel,’ said Coburg.

Norma Henderson turned towards Rosa and enquired, intrigued: ‘Pardon me for asking, Mrs Coburg, but aren’t you Rosa Weeks, the singer? I’m sure I recognise you from when Eric and I saw you at the Ritz about a month ago.’

‘Yes, that’s me,’ said Rosa.

‘You were wonderful!’ beamed Dorothy. ‘Wasn’t she, Eric?’

‘Yes. Very good,’ said Henderson, but reluctantly as if it wasn’t the done thing to throw compliments around.

Dorothy gestured towards the plaster cast that adorned Rosa’s left arm.

‘Bomb damage?’ she asked.

‘Dorothy, really!’ her husband rebuked her.

‘That’s all right,’ said Rosa. ‘No, an accident, I’m afraid.’

‘Difficult to play the piano, though,’ said Dorothy sympathetically.

‘Dorothy!’ repeated her husband, sharper this time.

‘Honestly, I’m not offended, Mr Henderson,’ said Rosa. ‘Your wife is just being caring. The answer’s yes, it does make it difficult to play, but I can vamp the bass notes to a degree. And the plaster cast will be coming off very shortly and I hope I’ll soon be able to get back to normal.’

Another heavy shower of rubble rained down on the roof of the shelter, this more sustained, and the occupants once again exchanged concerned looks.

‘I think it’s going to take a long time for any of this to feel normal,’ sighed Marsden.

CHAPTER TWO

Sunday 15th September 1940

The all-clear was sounding as dawn broke and the centre of London slowly came back to life. At the Savoy the crowd of people who’d sought shelter there the previous night were making their way out, most of them still stunned at the opulence of the basement shelter, and their talk was of the beds and the sheets and the tea and toast and jams they’d been given for breakfast. Even though they’d been in a separate area curtained off from the night quarters of the Savoy’s paying guests, none of them had ever experienced such surroundings, except those few who’d worked as maids in some of London’s grand houses in Belgravia or Kensington. But even they had to admit they’d never known such luxury.

The short man who’d led the crowd the night before stopped beside the same tall doorman who’d been on duty the previous evening, Lund Hansen, and asked: ‘Excuse me, but who was that gentleman who allowed us in last night?’

‘That was Mr Hofflin, the assistant manager,’ responded Hansen.

‘Would you tell him how much we appreciated what he did for us? Treating us like proper people.’

‘I will,’ said Hansen.

‘And can you tell him that Tom Huxton – that’s me – said if he’s ever Stepney way, there’ll be a drink or two for him behind the bar at the Bull and Bush, on me.’

‘I’ll tell him that as well,’ said Hansen.

‘Thank you,’ said Huxton. He turned to the young woman waiting for him, his 18-year-old daughter, who was standing with a young man of about the same age. ‘Come on, Jenny. Time to go home.’

Inside the Savoy, Willy Hofflin stood at the entrance to the restaurant and, with mixed feelings, watched the last of the crowd leave. On one hand, he felt he’d done a good thing by allowing them to stay the night in the Savoy’s shelter, especially the children and the women who were pregnant. But he was apprehensive of what Mr D’Oyly Carte would say when he discovered what he’d done, especially without consulting the general manager, Charles Tillesley. But Mr Tillesley had been at home, where there was no telephone, and Hofflin, as his deputy, had been in charge. As far as Hofflin had been concerned, the reputation of the Savoy had been at stake. If the visitors had turned violent and there had been a riot, children and pregnant women would certainly have been injured when the police moved in wielding their truncheons.

‘Excuse me, Mr Hofflin.’

Hofflin turned and found one of the waiters from the basement shelter standing behind him.

‘Yes, Sando,’ he said.

‘I’m afraid there’s been a tragedy in the shelter.’

‘What sort of tragedy?’

The man swallowed nervously, before whispering: ‘The Earl of Lancaster has been stabbed. Murdered.’

In Hampstead, Coburg and Rosa, along with the other residents of the block, left the damp, dark confines of the Anderson shelter and returned to their flat. The phone was ringing as they opened the door.

‘I bet that’s my parents checking to make sure we’re OK,’ said Rosa. She picked up the phone. ‘Mrs Rosa Coburg,’ she said with a smile at Coburg. Then the smile vanished and she said, rather more formally: ‘Yes, certainly. He’s here.’ She held out the phone to Coburg. ‘It’s a Mr Rupert D’Oyly Carte from the Savoy Hotel.’

Coburg took the phone from her.

‘Edgar Coburg,’ he said.

‘Chief Inspector Coburg,’ said D’Oyly Carte, ‘I apologise for troubling you so early on a Sunday morning. I got your telephone number from your brother, Magnus. He’s often been a guest here at the Savoy.’

‘How can I help you?’ asked Coburg.

‘I’m afraid there’s been a murder in the hotel’s air raid shelter in the basement. The Earl of Lancaster appears to have been stabbed to death. It’s a very delicate situation and I’d be most grateful if you would come.’

‘Certainly,’ said Coburg. ‘I’ll be with you shortly.’

He hung up and looked at Rosa. ‘There’s been a murder at the Savoy.’

‘Yes, I heard,’ said Rosa. ‘D’Oyly Carte? As in the Gilbert and Sullivan operas?’

‘That was his father, Richard,’ said Coburg. ‘But the answer’s yes, because Rupert inherited the Savoy Hotel from his stepmother.’

‘Your family knows some very rich people,’ observed Rosa.

‘Magnus moves in different social circles from me,’ said Coburg. ‘I’m afraid I have to go. I’ll have breakfast when I get back, but don’t wait for me. You must be hungry.’

‘I am,’ said Rosa. ‘I’ll do some toast to keep me going until you return. Are you going to pick up Sergeant Lampson?’

‘No. It’s Sunday and he doesn’t get to spend much time with his son. I’ll just go to the Savoy and see what the situation is, and I’ll bring Ted in if I need to.’ He pulled her to him and kissed her. ‘I’m sorry about this,’ he apologised. ‘It’s one of the drawbacks of being married to a police officer.’

‘I forgive you,’ she said. ‘In your case, the benefits outweigh any drawbacks. I wouldn’t have it any other way.’

When Coburg walked through the main entrance of the Savoy, the first person he saw was Inspector Arnold Lomax from the Strand police station, standing by the reception desk. So, I’ve been pre-empted, he thought ruefully. And by someone who hates my guts.

There was no mistaking the undisguised anger in Lomax as he saw Coburg. The inspector was a short, thin man in his early fifties with a sallow complexion, whose well-worn clothes – the faded, pale grey suits he habitually wore – always looked as if they were made for someone larger. His thinning hair was stuck down with grease, and Coburg was fairly sure he greased his thin moustache as well. Lomax’s face twisted into a snarl as he saw Coburg.

‘What the hell are you doing here, Coburg?’ he demanded angrily.

‘I had a telephone call from Rupert D’Oyly Carte, the owner, asking me to come,’ said Coburg.

‘If it’s about the murder, you can go again,’ snapped Lomax curtly. ‘We received the call at the Strand, so it’s my shout.’

Coburg shrugged. ‘That suits me,’ he said.

He turned to go, and Lomax called after him: ‘What, no clever response? No calling for your high and mighty aristocratic pals?’

‘It’s your shout,’ said Coburg. ‘I didn’t know that. I received a telephone call asking me to come, which I did. I assumed it was all above board, official.’

‘Well, it wasn’t,’ snapped Lomax. ‘And just to let you know, the case is as good as wrapped up. We’re pretty sure who did it: the Earl of Lancaster’s estranged son, William, who was part of the invasion the previous night. I’ve sent my sergeant to have him picked up and brought in.’

‘What invasion?’ asked Coburg, puzzled.

‘See?’ Lomax smiled smugly. ‘You don’t know everything.’

‘What invasion?’ repeated Coburg.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ said Lomax. ‘You’ll find out in due course. In the meantime, I’m in charge of this case and at this moment in time you’re just a member of the public. So I’ll ask you to leave so I can get on.’

‘In that case I’ll go home and have some breakfast,’ said Coburg.

Lomax walked off, a smug expression on his face, and Coburg headed for the exit, but before he reached it the figure of Charles Tillesley, the Savoy’s general manager, came hurrying to block his path.

‘Mr Coburg,’ he said. ‘I’m so sorry. I heard the scene between you and Inspector Lomax just now …’

‘There was no scene,’ said Coburg. ‘I just told him that Mr D’Oyly Carte telephoned me and asked me to call …’

‘That was my doing,’ said Tillesley. ‘I’m sorry. I hadn’t realised that someone had also informed the hall porter and told him to telephone the local police station.’

‘It doesn’t matter,’ said Coburg. ‘The police are on the scene and that’s all that matters. And, according to Inspector Lomax, he has the case well under control. He told me he has a suspect who’s about to be taken into custody, so I doubt if there’s anything I can do to assist. And, as you will have heard, he would prefer it if I wasn’t involved. So please pass on my thanks to Mr D’Oyly Carte for his telephone call, but tell him that it seems my services are not required.’

‘But they are!’ burst out Tillesley. He looked anxiously towards the door through which Lomax had disappeared, then turned back to Coburg, lowering his voice as he hissed urgently: ‘The person he accuses.’

‘The son of the dead man, the Earl of Lancaster,’ said Coburg.

‘Lady Lancaster is convinced the inspector’s wrong.’

‘That’s something she’ll have to take up with Inspector Lomax,’ said Coburg. ‘It’s his case, not mine.’

‘She’s attempted to talk to him, but he refuses to listen to her.’

‘I’m very sorry, but—’ began Coburg.

‘Please, Mr Coburg, even if not in your official role, won’t you talk to her? Hear what she has to say?’

‘Please, Mr Coburg,’ said a woman’s voice, and Coburg turned to see a tall, elegant woman in her fifties looking at him in appeal, and recognised her from an evening at his brother Magnus’s a year or so earlier.

‘Lady Lancaster,’ said Coburg, with a polite bow of his head.

‘I know what you say is correct, that protocol demands that Inspector Lomax is in charge of the case. So be it. I appeal to you not as a police officer, but as a man who I know to be capable of listening and understanding why my son could not have killed my husband.’

Coburg hesitated. I should not even be considering this, he thought to himself. It’s not my case. Inspector Lomax is in charge.

The problem for Coburg was that he knew Lomax, and had no respect for him. In Coburg’s view, Lomax was lazy, someone who took the easiest and simplest route when carrying out an investigation dismissing nuances or anomalies that didn’t fit with his view of a case. The situation was made worse because he and Lomax had a history: on at least two occasions, Coburg had cause to intervene in a case of Lomax’s when he knew the inspector to be so dramatically wrong that it could well result in an innocent person going to the gallows. For his part, Lomax made it very clear that he resented Coburg’s background of privilege: the son of an earl, and the rumours that, with a name like Saxe-Coburg, he was related to the royal family. As far as Lomax was concerned, those were the reasons that Coburg had advanced in the police force to the position of chief inspector, while Lomax remained just an inspector: the social elite taking care of one of their own, and nothing that Coburg could say in his defence would alter Lomax’s view of him.

‘Please, Mr Coburg, if you could just spare me five minutes of your time and hear what I have to say.’

‘You can use my office,’ offered Tillesley, adding his voice to the appeal.

‘Very well,’ said Coburg. ‘But unfortunately, Lady Lancaster, I doubt if it will change the situation. As a police officer, I’m bound by the rules. I can listen to you, but I cannot intervene.’

‘Just to talk to you will ease my heart,’ she said.

Edgar, Coburg mentally chastised himself as he followed Lady Lancaster and Tillesley towards the general manager’s office, you’re too soft for your own good.

CHAPTER THREE

‘Inspector Lomax mentioned an invasion last night,’ said Coburg as they mounted the carpeted stairs to the first floor where the general manager’s office was situated.

‘Yes. About forty people from Stepney, I believe,’ said Tillesley. ‘They’d seen our advertisement about the air raid shelter in our basement. The board had suggested putting it in the newspapers. So many people are fleeing London with this dreadful Blitz that it was felt it would be a good idea to reassure our patrons that if they stayed at the Savoy they would be able to do so in complete safety.’

‘Yes, I saw the advert in The Times,’ said Coburg. ‘It also emphasised the luxurious aspect of the shelter, which might have aroused strong feelings in some sections of society.’

‘That does seem to be the case,’ said Tillesley, a tone of regret in his voice. ‘That wasn’t the intention, of course; the last thing we wanted was to stir up social antipathy towards the hotel. It was just to reassure prospective guests that they would receive the same standard of service and hospitality they’ve been used to at the Savoy, that there would be no lowering of standards just because of the bombing. Sadly, it seemed to anger the people who arrived last night.’

‘You weren’t here?’

‘No, I was at home. My assistant manager, Willy Hofflin, was in charge, and he took the decision to allow them in. A decision which I endorse, especially after he explained his reasons to me. To protect the Savoy’s reputation.’

‘And was your son one of these invaders, Lady Lancaster?’ asked Coburg.

‘Yes, he has been living in Stepney for the past six months, ever since he left home. He said he wanted to live with the ordinary people. It angered his father very much. On reflection, I feel that may have been why William did it.’

‘Here we are. This is my office,’ said Tillesley. ‘I’ll leave you to talk.’ And he pushed open the door for them.

‘Thank you, Mr Tillesley,’ said Lady Lancaster. ‘You’ve been very kind.’

Coburg followed her into the general manager’s office. He had been here once before, a couple of years previously, when there’d been a problem with a member of some foreign royal family – Coburg couldn’t remember which – who’d woken up to find the prostitute he’d hired for the night had died in the bed next to him. Suspicions had been aroused by a number of livid bruises on her body. As it turned out the foreign royal was innocent of any brutality, the bruises had been inflicted by an earlier client, and the prostitute had died as the result of an accidental drug overdose. But the fact that the case had been dealt with, without any publicity, had earned Coburg the gratitude of Mr D’Oyly Carte and the board of the hotel, with the offer of a room any time he wanted it. It was an offer he had never taken up, feeling that it was a step on the path to accepting other gifts and bribes. I’m too much of a puritan, he’d decided somewhat ruefully at the time. And he still was.

Lady Lancaster and he sat down in two of the comfortable leather armchairs that furnished the room, along with Tillesley’s desk and high-backed chair.

‘I haven’t offered my condolences for the loss of your husband,’ apologised Coburg.

‘To be honest, Chief Inspector, he was no loss to me, or to William. He was a brute, crude, and if you ask around I’m sure you’ll find gossips eager to tell you about his affairs with all classes of women, most of whom he treated badly.’

‘I’m still sorry,’ said Coburg. ‘In this case, for the situation you now find yourself in. As I said, I have no jurisdiction in this case; that’s being overseen by Inspector Lomax …’

‘Who is an arrogant oaf with the intelligence of a gnat,’ said Lady Lancaster calmly.

Too true, thought Coburg. Aloud he said: ‘He is in charge of this case …’

‘He thinks William killed Hector based solely on the fact that William was here last night in the shelter, and that he was estranged from his father. I get the impression he refuses to consider any other possibility.’

‘The investigation has only just started. As far as I know, your son has not yet been taken into custody. I’m sure that when Inspector Lomax looks further into the case he will be open to other options.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t share your confidence, Chief Inspector …’

‘Please, Lady Lancaster, as I’m not supposed to be taking part in the enquiry, perhaps we’d better drop my official title for this conversation. Mr Coburg will be more appropriate, if that’s all right by you.’

‘Mr Coburg.’ She nodded. ‘I need to tell you about William, in case things go badly once he’s taken into custody.’

‘Why should they go badly?’

‘Unfortunately, because of his poor relationship with his father, William has developed a rather antagonistic relationship with authority.’

‘And this will not go down well with Inspector Lomax,’ said Coburg.

‘No. The inspector will not be sympathetic to him. I’m afraid it will only make him even more determined to find a case against him. But the truth is, Mr Coburg, that beneath William’s rather hostile attitude towards authority figures, he is a gentle soul. He is incapable of violence. That’s why he registered as a conscientious objector, refusing to be called up. And he’s a vegetarian, opposed to all forms of blood sports. It’s unthinkable that he would do something like this to anyone, let alone his father.’ She leant forward towards him, her expression urgent and imploring. ‘He needs someone on the inside to speak for him. Won’t you at least ask Inspector Lomax if he will let you talk to William? I’m sure William will talk openly and honestly to you, whereas with Inspector Lomax he will be …’

She struggled for words, and Coburg suggested: ‘Defensive, aggressive, and possibly insulting?’

She nodded. ‘Yes. You see, already you understand.’

‘I do, and I sympathise, but the situation is still the same. I have no power in this case.’

‘But you are a chief inspector, while Mr Lomax is merely an inspector.’

‘I would strongly advise against using words like “merely” when talking about Mr Lomax. It would only antagonise him further.’

‘You mean he’s already antagonised? Prejudiced against William?’

‘Inspector Lomax has his own views of the upper ranks of society.’

‘He doesn’t like us. That’s why he refused to talk to me.’

‘I doubt if it was an actual refusal. I expect he was preoccupied with acting on the initial information he had. He will talk to you.’

‘But will he listen sympathetically to what I have to say?’

‘I believe him to be sincere, despite his rather abrupt manner. I’m sure he will do his best to look into this case dispassionately, regardless of how your son acts towards him. After all, he is an inspector with a long experience in the police force.’ He stood up and added earnestly: ‘Your son will not be charged on prejudice, only if there is real hard evidence against him. If there is none, he will be freed.’

But inside, he thought unhappily: If only that were true.

‘You’re back quicker than I expected,’ said Rosa as Coburg entered their flat.

‘It turns out that my presence wasn’t required after all,’ said Coburg. ‘The local police station had also been informed and they’ve taken it on.’

‘They took long enough to tell you,’ commented Rosa.

‘It wasn’t that straightforward. The inspector who’s in charge is not someone I’m fond of, nor him of me, so we had a bit of a discussion.’

‘A row?’

‘Not from my perspective. I told him I was happy to leave everything to him. But then, as I was leaving I was collared by the dead man’s widow, Lady Lancaster, along with the manager of the Savoy, asking me to take over the investigation. I made the point that I couldn’t, that protocol was laid down: the case belongs to the first officer on the scene in an official capacity. And as I’d been asked to call in as a favour by Rupert D’Oyly Carte, my presence wasn’t officially sanctioned.’

‘Why did they want you to be in charge of it and not this other inspector?’

‘Because Inspector Lomax, the man in charge, has arrested Lady Lancaster’s son and she insists he’s innocent.’

‘Is he?’

‘I have no idea, and it’s not my case. So I suggest we head off somewhere, out of London. If the Germans mount another daylight raid, I don’t fancy spending the whole day stuck in that Anderson shelter.’

‘Me neither,’ said Rosa. ‘I mean, our neighbours are nice enough people …’

‘Now you’re just being polite,’ said Coburg. ‘Eric Henderson is one of the most boring and irritating people I’ve ever met. The idea of having to endure hour after hour of him …’

Rosa laughed. ‘So where shall we go? Where isn’t being bombed?’

‘I suggest we head northwest. Buckinghamshire. In particular, Chesham Bois. It’s in the Chilterns, and there’s no reason for the Germans to bomb it. There’s nothing there except a lovely little village, halfway between Amersham and Chesham. It’s far enough out of London, but not too far for me to be accused of excessive use of petrol.’

As they set off in the police car that Coburg had been forced to accept in place of his Bentley, which had been compulsorily garaged as part of Government restrictions on private travel, they saw that the skies above them were filled with German bombers. Harrying them were the British Spitfires and Hurricanes, who also had to contend with the German Messerschmidts protecting the German bomber fleet. More bombers were incoming, and the smaller British fighters buzzed around them like mosquitoes, tracers of bullets from the fighter planes hammering into the giant German bombers, the larger planes returning fire, and as they looked up they saw one of the British planes take a hit and spiral downwards, black smoke pouring from its fuselage. The next second something white appeared, growing larger like a flower suddenly blossoming, and they realised the pilot had parachuted out of his burning aircraft.

‘You don’t mind us running away?’ asked Coburg as he headed for the main road.

‘I don’t think of it as running away,’ said Rosa. ‘It’s us doing what we can to survive.’

They drove north, and the more distance they put between themselves and London, the clearer the skies became. The roads were almost completely free of traffic, most drivers restricted by petrol rationing, and many people deciding to seek shelter rather than drive. Once they’d left Harrow, Coburg took a route that avoided most of the built-up areas, making first for Rickmansworth and Chorleywood, then rolling down the hill from Amersham into the small, picturesque village of Chesham Bois.

‘We’re getting some curious looks,’ said Rosa.

‘It’s the car,’ said Coburg. ‘The sight of a police car always evokes interest, especially in a small place like Chesham Bois. I keep expecting to be stopped by the local constabulary and asked what we’re doing here.’

‘What will you say if that happens?’

‘I’ll produce my Metropolitan police warrant card and say we’ve come to talk to someone who has some information relating to a case we’re investigating.’

‘And my presence in the car?’

‘You’re a witness who knows the person we’re looking for.’

‘It’s a lie.’

‘Yes, it is, but I’m Detective Chief Inspector at Scotland Yard, so I doubt very much if that will be challenged.’

‘And if it is?’

‘I’ll say we discovered that the person we were looking for is no longer here, but I’m taking the opportunity to remind myself of what a wonderful village Chesham Bois is, and how I spent many happy days here as a child. There’s nothing like flattery to disarm people.’

‘You can be very devious.’

‘It’s not a lie. I did spend many happy days here as a child. My brothers and I used to come here as children with our father,’ said Coburg. ‘An old comrade of our father’s lived in the village and we used to listen to them swap stories.’

‘A comrade?’

‘They served together in the Boer War.’ He gave a weary sigh. ‘It seems that in recent times the Coburg men have spent a great deal of their time fighting, usually overseas. My father and other relatives during the Boer War. Magnus, myself and Charles during the First War, and now Charles is in a German PoW camp. It would be nice to think we’ll be the last having to do this.’

Coburg drove to a spot he remembered from his childhood visits, a wooded area carpeted with bluebells, the air heady with the scent of wild garlic.

‘Maybe we should move here,’ said Rosa wistfully. ‘It’s beautiful, and so peaceful.’ Then she corrected herself as they looked at the aerial battle still raging, but now many miles away from where they were: ‘Relatively peaceful.’

‘We have a duty to carry out,’ said Coburg. ‘Me, keeping the streets safe from crime. You, keeping people’s spirits up and – when your arm comes out of plaster – driving an ambulance and saving lives.’

‘Yes,’ she said with a sigh. She looked around at the pastoral scene. ‘It was worth coming out here just to remind ourselves of what we’re fighting to preserve.’

They spent the day savouring their surroundings, very aware of what a luxury this time was for them, and how different life was here, not so many miles from London. There were still the signs of war, road signs and fingerposts taken down to hamper the enemy in the event of an invasion – which was expected any time – and sandbags stacked up ready for use if needed. They had lunch at a pub, and Rosa commented that – with rationing – it was a pleasure to see real meat on the menu.

‘You’re in the country now,’ said Coburg. ‘There’s a lot of meat out there walking around.’

Finally, as the hours ticked past all too quickly, Coburg announced it was time to head home. ‘We need to get back before it gets dark and the blackout kicks in,’ he said.

The air battles were still going on as they neared the outskirts of London, although there seemed to be fewer German bombers in the sky. As they drove through Neasden they saw that the sky directly ahead of them was thick with black smoke pouring up from the ground, the smoke getting denser and bigger as they drew near to their home.

‘Something’s been hit,’ said Coburg.

‘Here in Hampstead?’ asked Rosa, bewildered. ‘There’s no military targets here.’

‘The Germans are just bombing everywhere to try to get the civilian population to demand the Government surrender,’ said Coburg. ‘They even hit Buckingham Palace again on Friday just to show that no one is safe.’

‘Yes, I heard it on the news,’ said Rosa. ‘They said it was the third time the palace had been hit.’

‘After the first strike the Government urged the royal family to leave the country, go to Canada, but they refused.’

‘“The children will not leave unless I do”,’ recited Rosa, recalling the Queen’s words in answer. ‘“I shall not leave unless their father does. And the King will not leave the country in any circumstances whatever.” Pretty stirring stuff.’

‘It was indeed,’ said Coburg. ‘Less demonstrative than Churchill’s style, but just as powerful.’

They turned the corner into their road, then stopped. Ahead of them, their block of flats had been half-demolished and was burning, the road filled with fire engines, hordes of firemen pouring water on the burning remains of the building from their hoses.

Coburg pulled the car to the side of the road and he and Rosa ran towards the blaze, but were stopped by a civil defence warden who said: ‘Sorry, you can’t get through.’

‘But that’s our home,’ said Rosa.

Coburg produced his warrant card and held it out to the warden. ‘I’m Detective Chief Inspector Coburg from Scotland Yard …’

‘I’m sorry, sir. I don’t care who you are, but no one’s allowed through.’

Suddenly a section of the upper part of the wall fell away and crashed to the ground in a cloud of dust and smoke, shaking the pavement beneath them, and then more of the building collapsed, forcing the firemen to retreat, but still keeping the jets of water from their hoses aimed at the ruined remains.

‘Did anyone get out?’ asked Coburg.

‘We don’t know yet, but it’s unlikely.’

‘What about the shelter?’

‘The Anderson shelter?’ The warden shook his head. ‘It took a direct hit. We can’t get to it until the fire brigade say it’s safe, but it looks like everyone who was in it’s dead.’

CHAPTER FOUR

Coburg put his arm round Rosa and led her back to the car. She was shaking.

‘All of them, dead,’ she said hoarsely, stunned. ‘And only last night we were with them.’

‘And we’d have been with them today if we hadn’t decided to take a break from that damned shelter,’ said Coburg grimly.

‘What are we going to do?’ asked Rosa. ‘Where are we going to stay tonight? Where are we going to stay, full stop?’

Suddenly she began to cry, her body shaking, and Coburg hugged her close to him.

‘It’ll be all right,’ he said, his tone gentle, but at the same time fiercely urgent. ‘We’ll get through this.’

‘I’m sorry,’ she apologised, straightening up and looking at him. ‘I didn’t mean to come over all “the little woman”.’

‘I know you didn’t,’ said Coburg. ‘And if I hadn’t seen all the things I did during the First War, I’d be in tears right now. Everything we had, gone. The people we shared the shelter with, all gone. But right now we take care of us tonight, and then tomorrow we start rebuilding.’

‘How?’ asked Rosa.

‘We’ll ask Magnus if we can stay at his London flat.’

‘Won’t he mind?’

‘He’s rarely there, and even less so since the Blitz began. And it’ll only be a short-term thing, a few days while we fix up somewhere else to live.’

‘So is that where we’re going tonight?’

‘No. I don’t have a key, and it’s unlikely Magnus will haul all the way from Dawlish Hall at this hour. Tonight, Mrs Coburg, I have something else in mind.’

Charles Tillesley, having been advised that Mr and Mrs Coburg had arrived at reception, came down from his office to greet them with a welcoming smile.

‘Mr and Mrs Coburg! This is a pleasure!’

‘We’ve come to take you up on your offer of a room for the night, if you have one spare,’ said Coburg. ‘Unfortunately our flat in Hampstead has just been struck by a German bomb.’

Tillesley stared at them, shocked. ‘How awful! But you are safe and uninjured?’

‘We weren’t there at the time. We returned home to find everything in ruins and the fire brigade doing their best to save the block, although we feel they’ll be unsuccessful. It was a direct hit.’

‘We do have a room, but it’s one we keep in reserve for staff who may have to stay overnight,’ said Tillesley apologetically.

‘Providing it has a bed and a bathroom, that’s all we need,’ said Coburg.

‘Please don’t misunderstand me,’ added Tillesley hastily. ‘It has all the necessary requirements we feel are important for a room at the Savoy. It is more than comfortable. I have stayed in it myself when the occasion arose. It is just not a suite of rooms, as many of our guests expect.’

‘Thank you, Charles,’ said Coburg.

‘And there is no need for you to vacate tomorrow,’ continued Tillesley. ‘How long will you need it for, do you think?’

‘Just the one night,’ repeated Coburg. ‘I’ll be telephoning my brother Magnus shortly to see if he will let us stay at his London flat.’

‘I assume you’ll be dining here this evening?’

Coburg nodded. ‘After our recent bad experience, I believe we deserve to treat ourselves.’

‘On the Savoy, as I said before, Mr Coburg,’ stressed Tillesley.

‘Thank you, Charles, but the rules for police officers on accepting gifts are quite strict, and I don’t want to be seen breaking them. But we do appreciate the offer.’

Tillesley called for one of the porters to escort them to the room on the second floor. Once they were in, Rosa stood and looked in awe at the luxurious furnishings and decor.

‘This is a spare room for the staff?’ she said, incredulous.

‘It is the Savoy,’ Coburg reminded her. ‘Now I must phone Magnus.’ He picked up the receiver and gave the switchboard operator the number for Dawlish Hall. The telephone at the other end was picked up almost immediately, and an elderly and rather prim Scottish voice announced: ‘Dawlish Hall.’

‘This is the Savoy hotel,’ said the operator. ‘We have a telephone call for you.’ Then, to Coburg: ‘You’re connected, caller.’

‘Good evening, Malcolm,’ said Coburg.

‘Master Edgar?’ said Malcolm, and Coburg could picture the smile on the elderly butler’s face.

‘Indeed it is,’ said Coburg. ‘Is my brother there?’

‘He is,’ replied Malcolm. ‘I’ll bring him to the telephone.’

There was a pause and Coburg heard muttering in the background, then the voice of his brother, Magnus, was heard.

‘Edgar. I hope you didn’t mind my giving Rupert your number. He was most distressed. A guest murdered, he said. The Earl of Lancaster, I believe.’

‘Indeed, but as it turned out my presence as a police officer wasn’t required. The nearest police station were also informed and a local inspector has taken charge.’

‘But you’re still at the Savoy, according to Malcolm.’

‘Alas, nothing to do with the investigation. Our flat took a direct hit in today’s air raids. The whole block was completely destroyed, so we’ve taken a room at the Savoy for the night.’

‘My poor dears. But you’re both all right, are you? Not injured?’

‘No, we were away from the area at the time. We only discovered the damage when we returned late this afternoon. We’re obviously having to find alternative accommodation, but it may take a few days, so I was wondering …’

‘The London flat,’ finished Magnus. ‘Absolutely. It’s yours for as long as you want it. You don’t have keys, do you?’

‘No.’

‘In that case I’ll travel up to town tomorrow and let you in. What time would suit you?’

‘Actually, I have things to do in the morning, report to Scotland Yard and then make the rounds of letting agents, so I wondered if you’d mind if you met with Rosa.’

‘Not at all,’ said Magnus, but now there was a note of reserve in his voice, the reason for it becoming clear with his next statement. ‘I’m looking forward to meeting my new sister-in-law. I had hoped to meet her at your wedding, or even before it.’

He’s annoyed because we didn’t invite him to the wedding, thought Coburg. Correction, because I didn’t invite him.

‘Where was it?’ continued Magnus, his tone still icy. ‘Registry office, I presume. You could have had it here, you know. The church is still part of the estate and Reverend Barnes would have been delighted to see a Coburg wedding take place there. And holding a reception here at the Hall would have cheered people up no end, especially at a time when they could do with cheering up.’

‘I know, Magnus, but we – I – wanted it low-key.’

‘Well you certainly got what you wanted,’ said Magnus, still disapproving. ‘But I’ll be delighted to meet your new wife tomorrow at the flat and give her the keys and show her where everything is. I can be there for ten thirty. Will that be all right for her?’

‘Will a bit later be all right? We need to go back to the flat and see if we can salvage anything from the wreckage. Personal items and such.’

‘What time, then?’

Coburg looked at Rosa questioningly.

‘If we go to the flat first thing, I should still be able to make ten-thirty,’ said Rosa.

‘Let’s say eleven,’ suggested Coburg. ‘Just in case things turn up.’

She nodded.

‘Rosa says—’ began Coburg.

But Magnus interrupted. ‘I heard. Eleven it is. I’ll see her there.’

‘I’ll give her the address,’ said Coburg. ‘And so you know what she looks like—’

‘I already know,’ Magnus interrupted again. ‘Malcolm saw a piece about the wedding in a newspaper. Not The Times or The Telegraph, one of the lesser ones. It had a photograph of the pair of you on the steps of the registry office with the caption: Jazz star weds aristocrat cop.’

‘Nothing to do with us,’ said Coburg. ‘I think these photographers hang around there in case someone turns up who they think might be interesting.’

‘In the photo it looked like she had an arm in plaster.’

‘Yes,’ said Coburg. ‘She got shot.’

‘She must be finding life with you to be dangerous,’ commented Magnus. ‘Tell her I’ll see her in the morning.’

Coburg hung up and looked at Rosa, who said: ‘So, he saw the piece about our wedding in the Daily Mirror.’

‘His butler, Malcolm, reads it.’ He gave a thoughtful frown. ‘I’m still not convinced that Ted didn’t leak it to someone and they passed it on. Ted’s parents, for example. They were very proud of him being best man.’

‘It sounds like your brother hasn’t forgiven us for not inviting him,’ said Rosa with a sigh.

‘Magnus has very traditional views about how things ought to be done,’ Coburg shrugged. ‘But he’ll be fine with you tomorrow. He’s an old-fashioned gentleman with perfect manners. And he’s nice, when you get to know him.’

‘But you’re not coming with me.’

‘I need to make arrangements for another flat for us.’

‘I heard Magnus tell you we can stay at his flat as long as we like.’

‘I’m sure we can, but I’d prefer to have our own place rather than be beholden to Magnus.’

‘You don’t get on with him?’

‘Oh, we get on well enough,’ said Coburg airily. ‘But sooner or later Magnus will be round all the time, poking his nose in, telling us what we can and can’t do in his place. It’s the way he is. And if I came with you tomorrow I’d lose the whole day, because once Magnus gets talking he goes on and on, and I need to get to work. I’ll see him later, when we’ve got things sorted out.

‘Right now, I suggest we have a bath to get rid of the stress of the day, and then go down to the restaurant.’

‘Mr Coburg!’ The woman’s voice stopped Coburg and Rosa as they were about to enter the restaurant. They turned and saw Lady Lancaster making for them.

‘The murdered man’s widow,’ Coburg whispered to Rosa. Aloud, he said: ‘Good evening, Lady Lancaster. This is my wife, Rosa.’

‘You’re staying here?’

‘Just for the one night. Unfortunately, our block of flats was bombed, so we’re officially homeless.’

‘How awful!’ She looked at them, puzzled. ‘But you’re here. And undamaged.’ She looked at Rosa’s plastered left arm and gave an embarrassed smile. ‘Well, not damaged today.’

‘No,’ said Rosa. ‘This happened just over a month ago.’

‘Luckily for us, we weren’t at home when the bombs struck,’ said Coburg.