Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

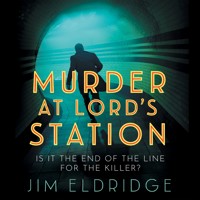

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: London Underground Station Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

April, 1941. At the former Whitechapel Road Underground station, repurposed as an air raid shelter since the onset of the Blitz, the body of a woman has been discovered, stabbed and eviscerated. With the ghoulish history of Jack the Ripper and his victims not far from their thoughts, Detective Chief Inspector Coburg and Sergeant Lampson are called from Scotland Yard to examine the scene. In the station's dark and dingy tunnels they stumble across a battered Victorian doctor's case containing surgical tools. Has it been deliberately left to be discovered? With the spectre of London's most famous killer looming large over their investigation, Coburg and Lampson are under pressure to swiftly conclude this very difficult case as more victims come to light. But that proves to be a challenge when King George and the Prime Minister Winston Churchill seek their help with a puzzling inquiry that also has links to Whitechapel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 402

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

MURDER AT WHITECHAPEL ROAD STATION

JIM ELDRIDGE

4

5

For Lynne, who lights up my life

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Monday 31st March 1941

The phone in DCI Saxe-Coburg’s office rang and was picked up by Coburg’s detective sergeant, Ted Lampson.

‘DCI Coburg’s office,’ said Lampson.

‘Is that you, Ted?’ asked a male voice. ‘It’s Joe Harker at Whitechapel.’

‘Joe,’ said Lampson cheerfully. ‘Long time no speak. How are you? If you’re after my guv’nor, he’s in with the superintendent at the moment.’

‘Actually, it’s you I was after,’ said Harker. ‘We’ve got a murder here at Whitechapel and there’s a couple of strange things about it. Really strange. And knowing that Scotland Yard will be getting involved, I wanted to make sure we had the best people. That’s why I’m calling.’

‘Flatterer.’ Lampson chuckled. ‘Who is it? Who’s been murdered?’

‘It’s a woman. By all accounts she was a prostitute.’

‘And what’s so strange about it?’

‘I’d like it if you could come and see for yourself. You and your guv’nor, that is.’

‘Sounds mysterious,’ said Lampson.

‘Mysterious is the right word for this one,’ said Harker. 8‘We’ve left everything in place at the scene so you can see it just as it was found.’

‘And where is the scene?’

‘The old Whitechapel Road Tube station. Also known as St Mary’s.’

When Coburg returned, Lampson told him about the phone call.

‘He didn’t say what was particularly mysterious about the situation?’ asked Coburg.

‘No, he said it was best if we saw for ourselves.’

Lampson was elected to drive as he knew the way around Whitechapel better than Coburg.

‘How reliable is Sergeant Harker?’ asked Coburg as they made their way east from Central London.

‘Very,’ said Lampson. ‘If he says there’s something strange, there is.’

‘He didn’t give you any idea as to what it was?’

‘No. All he said was they’ve left everything as they found it for us to look at, before they have the body taken away.’

‘A murdered prostitute,’ said Coburg thoughtfully. ‘In Whitechapel.’

Lampson chuckled. ‘Don’t start trying to guess. From the way Joe was talking, it’s best if we keep an open mind on what we’re about to see. So, no jokes about Jack the Ripper. Prostitutes are getting killed all over the place. Not just in Whitechapel. Maida Vale. Ealing. Hampstead. Soho.’

‘Yes, alright,’ said Coburg. ‘How long have you known Sergeant Harker?’

‘Years,’ said Lampson. ‘We both used to play football for the Whitechapel police squad. We were both defenders; Joe was right 9back and I was left. That was when we were both constables. In the end I found it a bit much having to travel to Whitechapel all the time, so I had to abandon it. But Joe kept it up. He’s a good bloke.’

They pulled up outside the former Whitechapel Road Tube station and saw that part of the front wall was missing. Attempts had been made to fix wooden boards across the gap, but it looked a precarious piece of carpentry.

‘It got hit during the early days of the Blitz,’ said Lampson. ‘Badly damaged. We won’t talk about that in front of Joe. His sister, Joan, was killed in the blast.’

Lampson then went on to fill Coburg in on the recent history of the abandoned station.

‘The station was closed in 1938. Before then it was always a bit of an oddity. A lot of people used to confuse it with Whitechapel station. When it was opened it was known as St Mary’s Whitechapel Road. The thing is the station was very close to Whitechapel and Aldgate East Tube stations. In fact, Aldgate East was only a couple of hundred yards from St Mary’s Whitechapel Road, so it was decided to shut Whitechapel Road and let Aldgate East be the main station for the area.

‘When the war began, the borough of Stepney leased the abandoned station from London Transport for use as an air raid shelter. Because the railway tracks were still in use, they bricked up the edges of the platforms to make the area safe for people sheltering in it. Joe’s sister, Joan, was going in when the front of the old building was hit by a bomb, destroying part of it.’

‘Hence the boards that have been put up,’ said Coburg.

‘No, the boards were put up after it was hit a second time, a couple of months later, wrecking the repair work that had been done the first time. Remember, this area, the whole of the East 10End, has suffered more from the bombing than most other areas of London.’

Coburg reached for the handle of the passenger door. ‘This is where we get out, I presume?’

Lampson nodded. ‘The entrance to the old station is a brown door a bit further on. Joe told me to look out for it. He said he’ll be down on one of the former platforms, where the air raid shelter is, waiting for us.’

They got out of the car and locked it. Then Coburg followed Lampson along Whitechapel Road. After a short while they came to a nondescript-looking door sandwiched between two boarded-up shops.

‘This is it,’ said Lampson.

They walked into what looked to be a rear service entrance to the station. The former ticket office had obviously been destroyed along with the front of the old station during the recent bombing. They walked down a circular staircase, which seemed to go on for ever, before they came to what had once been a station platform. A brick wall had been erected at its edge, and as they arrived a train went past, and they saw the wall shake.

‘How safe is that wall?’ asked Coburg.

‘I’m told it’s safe enough,’ replied Lampson. ‘It may not stop a bomb, but we’re deep below ground and the only thing likely to mess it up is if a train hits it, which is unlikely.’

A tall man in the uniform of a police sergeant approached them from along the platform.

‘Joe Harker,’ Lampson muttered to Coburg, who stepped forward with his hand outstretched. ‘Sergeant Joe Harker, I presume.’

‘Indeed, sir,’ said Harker. ‘I’m glad you could come, Chief Inspector.’ 11

‘You told Ted it was strange.’

‘It is,’ said Harker. ‘If you’ll follow me.’

They walked along the platform, passing a few groups of people, mostly elderly or women with small children, who appeared to have set up camps.

‘People who are afraid to go up top,’ explained Harker. ‘This area’s been so badly bombed, and it’s not always at night. The Germans come along the Thames Estuary and this area’s one of the first built-up places they come to. Also, people want to know they’ve got a place here when they come down, and they like a spot further away from the edge of the platform.’

They reached a halfway point, where curtaining had been set up. The smell gave away what was behind the curtains.

‘Earth buckets,’ confirmed Harker. ‘They’re due to be cleared and changed later.’

He turned a corner and they followed him along a short corridor, which came out on the other platform.

‘Eastbound,’ explained Harker.

As they walked along this platform they passed more small groups of people who had set up camps, with mattresses and chairs.

At the far end of the platform they came to a hole in the brick wall. Harker produced a torch and switched it on, illuminating the darkness beyond the hole. They walked into what appeared to be an access tunnel.

‘There’s a warren of these tunnels from here,’ Harker told them. ‘They’re left over from when they were building the station way back.’

They walked along the narrow tunnel and Coburg saw that at various places there were alcoves leading off from the main tunnel, and some of the alcoves had further tunnels leading off into 12darkness. Coburg caught the smell of stale urine and excrement.

‘Toilets,’ he remarked.

‘Unofficial ones,’ said Harker. ‘Not everyone has the time to stand and queue by the earth buckets on the westbound platform.’

He stopped by a space where an alcove had widened out into a sizeable aperture and shone his torch into it. A uniformed constable was guarding the area and he saluted as the visitors arrived. He had set up an oil lamp to illuminate the large alcove, enabling Harker to switch his torch off.

‘PC Dixon,’ Harker introduced the constable.

Coburg and Lampson nodded to the constable, then turned their attention to the body of a woman, lying on her back on the floor at one side of the space. She was obviously dead.

‘Stabbed in the heart,’ said Harker. He reached down to take hold of the bottom of her long flowing skirt.

‘This is the first thing,’ he said.

He lifted the skirt and pulled it up to her shoulders, revealing the horror it had been hiding.

‘She’s been eviscerated,’ Harker said. ‘Her womb, her bladder, her intestines, everything down there cut out.’

‘Not left here?’ asked Coburg.

‘No. He must have taken them away with him.’

‘Who found her?’

‘A woman who came in to use it as a toilet in the early hours of the morning.’

‘Where is she? Can we talk to her?’

‘She went home as soon as the all-clear sounded. She was all for leaving after she’d found it, but there was a serious air raid on and her husband told her she’d have to wait. I’ve got her address. She reported it to one of the officials from the council who was 13down here, and he reported it to the local police as soon as the all-clear had gone.’ He looked at Coburg. ‘Seen enough?’

‘For the moment,’ said Coburg. ‘I assume the medics have been contacted.’

‘They have,’ said Harker. ‘Hopefully the doctor’s on his way. But the body isn’t the strangest thing.’

He led them to a side wall where they saw what appeared to be a large leather case on the ground.

‘There,’ said Harker.

‘It looks like an old-fashioned surgeon’s case,’ said Coburg.

‘That’s exactly what it is,’ said Harker. ‘It’s full of surgeon’s tools. I’ve seen one just like it in a local museum. They reckon it’s from Victorian times.’

Coburg and Lampson exchanged looks. Harker gave a weary sigh. ‘Someone’s sending us a message about You-Know-Who.’

‘Perhaps, when the doctor arrives, he might be able to throw some light on the old case,’ suggested Coburg.

‘He might,’ said Harker.

Coburg caught the note of doubt in the sergeant’s voice and looked at him inquisitively.

‘There are two doctors on call for this area from the London Hospital,’ explained Harker. ‘If it’s Dr Webb, we’ve always found him helpful. Dr McKay, on the other hand, can be rather … dour.’

‘Not helpful?’ asked Coburg.

‘He’s a man of strong opinions who doesn’t suffer fools gladly. And he seems to view most people as fools. Or, at least, people who take up his time unnecessarily when he’s got more important things to do.’

‘Such as?’ 14

‘I get the impression he’d prefer to be treating sick people than looking at corpses.’ He sighed. ‘But then, he doesn’t seem fond of sick people either. The fact that the doctor hasn’t arrived yet suggests to me that today’s on-call doctor is Dr McKay.’

The sound of footsteps approaching made them turn towards the entrance. A constable, carrying a torch, entered, accompanied by a short, thin, bearded man in his late fifties.

‘Dr McKay’s here, sir,’ announced the constable.

‘What have we got?’ demanded McKay gruffly.

‘A dead woman who’s suffered extreme injuries,’ said Harker.

McKay approached the dead woman, then carefully lifted the bottom of her skirt and raised it.

‘My God!’ he said. ‘These aren’t just extreme injuries. She’s been eviscerated.’

‘Yes,’ said Harker. He gestured towards Coburg and Lampson. ‘These gentlemen are from Scotland Yard. DCI Coburg and DS Lampson.’

‘Why have you called them in?’ demanded McKay disapprovingly.

‘Because of something we found at the crime scene,’ said Harker. He pointed at the ancient doctor’s case.

McKay walked to it.

‘Be careful about touching it,’ cautioned Coburg. ‘We’ll need to check it for fingerprints.’

McKay looked at Harker. ‘Has it been opened already?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ said Harker. ‘I opened it.’

‘So there’ll already be fingerprints on it.’ McKay took out a handkerchief, with which he covered his hand and flicked 15the lock. The case fell open, revealing a set of old-fashioned surgical instruments.

‘Victorian,’ announced McKay.

‘You’re sure?’ asked Coburg.

‘Absolutely,’ said McKay curtly. ‘My grandfather had one identical to this.’

‘Where did he practise?’ asked Coburg.

‘Why?’ asked McKay.

‘I wondered if it was a design made to a particular area.’

‘No,’ said McKay. ‘But, for the record, my grandfather practised in Edinburgh.’ He turned to Harker. ‘I brought an ambulance with me to take the body. I told them to wait outside until I gave them instructions.’ He turned to the constable. ‘You may instruct them to come down and collect the body.’

The constable departed, and McKay stood looking thoughtfully down at the body. ‘Do we know who she is?’

‘Not yet,’ said Harker. ‘There’s been no purse or any sort of identification found here. We’ll start asking questions locally once she’s been taken away.’

‘I suggest a police photographer takes a picture of her, which we can show around,’ said Coburg. ‘With your permission, of course, Doctor.’

McKay nodded in agreement.

‘I’ll send a photographer to the London,’ said Harker.

McKay turned to Coburg. ‘What’s your opinion of the surgeon’s case being left so obviously, Chief Inspector?’

‘We’ll be looking into that,’ replied Coburg guardedly.

The doctor gave a sniff to show he wasn’t impressed by this answer. 16

There were footsteps outside, then the constable returned, accompanied by three ambulance men carrying a stretcher. McKay watched as they loaded the dead woman’s body onto the stretcher, then he followed them out after saying, ‘I’ll give you my report, Sergeant, after I’ve examined her.’

Coburg waited until he was sure the doctor was well out of earshot before he commented, ‘Not exactly a ray of sunshine, is he.’

‘He is what he is,’ said Harker resignedly. He pointed at the surgeon’s case. ‘What do you want to do about this?’

‘We’ll take it with us for a proper examination. If you need it, it’ll be at Scotland Yard. Can you get your men to do a detailed inspection of the station, checking in case there’s anything that looks suspicious. After all, you know this place better than we do, so if there’s anything that looks odd – like the surgeon’s case – your people are more likely to spot it. I hope you didn’t mind my suggesting that your people arrange the taking of the photograph. My thinking is that your men know the people of this area and will know best how to use the photograph of the dead woman, who to specifically show it to and talk to, for example.’

‘That makes sense,’ said Harker. ‘We’ll start with the people who were in the air raid shelter last night, see if anyone knows who she is. And if anybody saw her going off with any men.’

‘Excellent,’ said Coburg. ‘Thank you, Sergeant.’

As Coburg and Lampson left the station and walked to their car, carrying the case, they were watched by a shadowy figure on the other side of the road.

So, they’ve taken the first two bites of the bait. The Watcher smiled. The body and the case. Good. It’s begun.

CHAPTER TWO

Rosa walked with John Fawcett, her producer, into the small theatre deep below ground at the BBC Maida Vale studios.

‘You’ve been here before, I believe,’ said Fawcett.

‘Yes. Before the war,’ said Rosa. ‘It was a programme of piano jazz, and I was lucky enough to be one of the artistes featured.’ She looked around at the rows of plush red seats. ‘I love this theatre. Three hundred seats means it has an intimacy you rarely get in the larger concert halls.’

‘Which is why I thought it would be perfect for Rosa Weeks Presents,’ said Fawcett.

He strolled down the aisle to the slightly raised stage where two chairs had been placed by the grand piano. ‘We’ll be broadcasting the first show next Tuesday evening. I thought we could chat through the programme and presentation, see what we’ll need. Did I tell you your guests for the first show?’

‘Yes. Flanagan and Allen, and Vera Lynn. That’s wonderful. You were lucky to get them; they’re so busy.’

‘I’ve known them for some time, worked with them before on different shows, which helped. I also think they were quite intrigued by the idea of doing a show with just a small trio instead of the usual big band. Do you have anyone in mind for your drummer and bass player, or do you want me to find your sidemen?’

‘I was going to ask if you’d agree to Wally Dawes and Eric Pickup. Wally is a drummer I’ve worked with before at different 18venues, and Eric I’ve worked with on recordings.’

Fawcett looked thoughtful, then said, ‘Yes, I’ve worked with Eric, he’ll be superb. But are you sure about Wally?’

‘Why?’ asked Rosa.

‘Well, I haven’t worked with him for a while, and he was always good, but lately I’ve heard he’s got a bit of a drink problem.’

‘A drink problem?’ said Rosa, surprised. ‘I hadn’t heard that. But then, I haven’t seen him for a while either. The war has interrupted a lot of sessions. But if you’d prefer another drummer?’

‘No, no,’ said Fawcett. ‘If he’s your choice, I’m happy to try him out. I do remember him before the war. Always excellent, especially on the backbeat. However, I believe he was caught in a raid that brought down part of the building he was in, and he’s had some difficulty recovering. Shall we try a session with you, Wally and Eric and see how it works out? If he’s alright, I’m happy to go ahead. When are you free? I know you’re driving the ambulance …’

‘For this, my boss, Mr Warren, has said he will give me whatever time off I need.’

‘In that case, how about the day after tomorrow? Wednesday. I suggest early afternoon.’

Rosa smiled. ‘Seeing how Wally is after lunchtime?’

‘Just a cautionary measure,’ said Fawcett. ‘I’ll make the arrangements with their agents. Will half past two suit you?’

‘Half past two will be perfect.’

‘We won’t have Flanagan and Allen or Vera for the run-through, but I’ll be happy for you to take the vocals. After all, I just want to see how the trio fits together. Bud and Chesney will be doing 19“Underneath the Arches” and “Shine On, Harvest Moon”; and Vera will be singing “We’ll Meet Again” and “Red Sails in the Sunset”.’

‘Excellent,’ said Rosa. ‘I’ve got the music at home so I’ll practise those.’

‘I was thinking for your opening song to be “Up A Lazy River”, if that’s alright with you. I know you admire Hoagy Carmichael. I feel “Lazy River” has a gentle quality about it that will be perfect for bringing the audience listening at home in. My thought is to begin with the opening verse and chorus, then you say: “Good evening, listeners. I’m Rosa Weeks and this is Rosa Weeks Presents. In tonight’s show you’ll be hearing from my special guests, Flanagan and Allen and Vera Lynn, and I’ll be putting in a few songs of my own. I hope you enjoy the show.” Then you return to the song. We’ll have applause from the audience, which someone will signal, and then you do your second number, after which we’ll have Bud and Chesney. Then Vera comes in to do a number; then you do one. Then Vera does her second, followed by you, then Bud and Chesney. And finally, you again to round off the show. Then, while you and the trio play out with a musical version of “Lazy River”, an announcer comes on and gives the closing credits, and we end with more applause from the audience. How does that sound?’

‘It sounds very well worked out,’ said Rosa. ‘Very impressive. I hope the boys and I can do you justice.’

‘I’m confident you and Eric will,’ said Fawcett. ‘However, I reserve judgement on Wally until the day after tomorrow.’

As Coburg and Lampson entered the large reception area at Scotland Yard, Coburg noticed the duty sergeant at the desk, Sergeant Crawford, hailing him and walked over. 20

‘Yes, Dan?’ asked Coburg.

‘Superintendent Allison is looking for you,’ said Crawford. ‘He seemed quite agitated about something.’

‘Did he say what it was about?’

‘No, just asked where you were. In fact he’s phoned down twice since to see if you’d come in, so I get the impression that whatever it is, it’s urgent.’

‘Thanks, Dan. I’ll go and see him straight away.’

Coburg and Lampson made their way up the wide marble staircase to the first floor and Coburg headed for the superintendent’s office, while Lampson made for theirs. Coburg knocked at the superintendent’s door, and at the command ‘Enter’ walked in.

‘Ah, there you are at last, Coburg,’ said Allison impatiently. ‘Where have you been?’

‘Out on a case, sir.’

Instead of asking for details of the case, the superintendent said brusquely, ‘Forget that. You’re to go to the palace at once.’

Coburg looked at the superintendent and asked, puzzled, ‘Which palace, sir?’

There were so many palaces in London: Lambeth Palace, Alexandra Palace, Crystal Palace, not to mention the royal palaces. Allison looked at him in disapproval, as if his chief inspector was being deliberately obtuse. ‘Buckingham Palace,’ he said. ‘The King wishes to talk to you.’

Coburg was on the point of asking, King George VI?, just to make sure he’d heard right, but a look at the expression of annoyed impatience on Allison’s face made him instead ask, ‘For what purpose, sir?’

‘You’ll be told that when you meet him. I told the palace 21you’d be there as soon as you returned. Unfortunately, I had no way of knowing where you and Sergeant Lampson had disappeared to. You left no message of your whereabouts.’

‘No, sir, for which I apologise. We’d had a call about a dead body in Whitechapel.’

‘Whitechapel? Couldn’t the local force handle that?’

‘It was the local Whitechapel force who contacted us because of some strange circumstances in the case.’

The superintendent chose not to ask further questions about Whitechapel; it obviously held little interest for him. Certainly not the same interest as a request from the King of England.

‘Very well, but I urge you to get to the palace.’

‘Yes, sir. I’ll just inform Sergeant Lampson.’

Allison shook his head. ‘Just your presence is requested.’ He looked at his watch. ‘I suggest you leave now. We don’t want His Majesty to feel he has been kept waiting.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Allison stopped Coburg as he was about to leave. ‘One thing, Chief Inspector. I have to make a telephone call to alert the palace that you are on your way, and another to a third party. I understand that there may well be someone else in attendance when you meet the King.’

‘Yes, sir. May I ask who?’

‘As that depends on whether this person is available, I’m afraid you will have to wait and see who awaits you.’

All very mysterious, thought Coburg as he walked towards his office. Despite the superintendent urging speed, he couldn’t just leave without letting Lampson know he was going out. He opened the door of his office and looked in. Lampson looked enquiringly at him. 22

‘Everything alright?’

‘Hopefully I’ll tell you when I come back,’ said Coburg. ‘I’ve got to go out.’

With that, he pulled the door shut and made his way downstairs and out to his car.

On his arrival at the gates of Buckingham Palace he was stopped by two uniformed policemen. He showed them his warrant card and told them, ‘I have an appointment with His Majesty.’

They had obviously been briefed to expect him, because he was waved through, after being directed to drive through the arch to the rear of the palace.

No sooner had he parked than a man in a footman’s uniform appeared and asked, ‘DCI Saxe-Coburg?’

‘Yes,’ said Coburg.

‘If you’ll follow me,’ said the footman. ‘His Majesty is in his study. He’s expecting you.’

Coburg followed the footman into the palace, then up some stairs and along a series of corridors, until they arrived at a large oak door. The footman knocked at the door, then opened it and announced: ‘Detective Chief Inspector Saxe-Coburg, Your Majesty.’

The footman opened the door wider and Coburg entered.

The King had been seated in an uncomfortable-looking wooden armchair and he rose to his feet as Coburg entered.

What do I do? wondered Coburg. Do I bow? Offer to shake hands?

His dilemma was resolved when the King held out his hand towards Coburg and they shook hands.

‘Thank you for coming, Chief Inspector.’ 23

‘I’m flattered to be asked, Your Majesty,’ said Coburg. ‘I am at your complete service.’

The King gestured for Coburg to sit, then seated himself.

Although Coburg had seen the King in newsreels, it was the first time he’d seen him face to face. A slender man in his mid-forties of medium height, there were still traces of the stammer that had plagued him in his young life, but he’d obviously learnt to control it, taking short breaks between sentences. Coburg recalled being told that an Australian speech therapist called Lionel Logue had been the one who worked with him to help him overcome his stammer, and that the King – although at the time of this therapy he’d still been Prince Albert, only becoming King after the abdication of his elder brother, formerly King Edward VIII and now the Duke of Windsor, who abandoned the throne in order to marry the divorced Mrs Wallis Simpson – had worked on his vocal and breathing exercises with his wife, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, now Queen Elizabeth.

‘Saxe-Coburg,’ said the King thoughtfully. ‘I assume we must be related to some degree.’

‘It’s possible, sir. Although I’ve never really explored my family history.’

‘Your father was the Earl of Dawlish, a title now held by your elder brother, Magnus.’

‘That’s correct, sir.’

‘The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha was founded in 1826, by Ernest Anton, the sixth duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield. It was a cadet branch of the Saxon house of Wettin. Various branches of the family were extant throughout Europe in the last century. Ernest Anton’s younger brother, Leopold, became King of Belgium in 1831, and his descendants continue 24to rule. It was Ernest’s second son, Prince Albert, who married my great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. Victoria was herself a niece of Ernest and thus a first cousin of Prince Albert. There are other branches of the family in Portugal, Austria, Bulgaria and even Brazil. So it is quite feasible that somewhere along the line, some of our mutual ancestors intermingled.’

‘Yes, sir.’

The King smiled. ‘When I was growing up, part of my education consisted of my family history. It has stuck with me rather than my deliberately seeking it out to study. Of course, the family interest in the Saxe-Coburg-Gothas rather waned after my father changed the family name to Windsor in 1917, but I’ve always been interested in where we came from. It might be of interest to ask your brother about your family’s particular roots to see where we intersect.’

‘I will, sir. Thank you.’

‘However, that is by the by. The reason I have asked you here is because one of my valets has disappeared.’

‘Disappeared?’

‘Yes. Bernard Bothwell. Three days ago he did not report for work. A messenger was despatched to his residence to see if he was indisposed, but his family reported that he seemed to have vanished. He left for work as usual, but never returned home. They reported his disappearance to the local police, who checked the hospitals and other places where he might have gone, but there has been no trace of him.’

‘So the local police are aware of his disappearance?’

‘Yes. But that is all they know.’ He paused, then said, ‘Unfortunately, coinciding with his disappearance, a personal item of mine has also gone missing.’ 25

Before he could continue, they were interrupted by the door opening and the bulky figure of a large man hurried in.

‘My apologies, Your Majesty,’ boomed the new arrival in fruity rich tones that Coburg immediately recognised as belonging to the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

Immediately, Coburg rose to his feet.

‘Detective Chief Inspector Saxe-Coburg,’ said Churchill, and walked towards Coburg, his hand outstretched. Coburg shook it. ‘I know your brother Magnus well. We were comrades in arms during the First War.’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Coburg. ‘He often talks of you.’

‘Well, I hope?’ asked Churchill.

‘He always sings your praises, Prime Minister.’

Churchill smiled. ‘A good man. A very good man. It was he who suggested we contact you about this appalling situation.’ He gestured at the chair behind Coburg. ‘Sit, man. Sit.’ He turned to the King and said, ‘Again, my apologies, Your Majesty. My lateness is due to reports of enemy action that came in this morning, which I needed to deal with. North Africa. Have you filled the chief inspector in on what has occurred?’

‘Only the disappearance of Bernard Bothwell. I was just about to inform him of my personal loss when you arrived.’

‘A watch,’ said Churchill. ‘And not just any watch. It was a gift to His Majesty from his late father, King George V, and therefore particularly precious. There is no doubt in my mind that this villain Bothwell has taken it.’

‘We cannot be certain of that, Winston,’ cautioned the King.

‘The disappearance of Bothwell and the disappearance of the watch at the same time shows the two are connected. Find 26Bothwell and we find the watch. Or, at least, what he did with it. I’m sure you agree, Chief Inspector?’

‘With respect, Prime Minister, I agree with His Majesty. There may be another explanation. My experience as a police detective has taught me it is best to keep an open mind on any investigation.’

‘Hmph,’ grunted Churchill, obviously not pleased with Coburg’s reaction. ‘Very well. But it is important that this timepiece is recovered. And without publicity. We cannot let news of this theft, if that is what it is, and the strange disappearance of the King’s valet become public knowledge. It could lead to a loss of morale in the security surrounding the royal family, and that is the last thing we can afford to happen. So, you can use every instrument at your disposal, but the item that is sought – this precious watch – is not to be mentioned outside this room. Concentrate on the valet. His disappearance is already known to the local police, so we can contain any harm the story might do as a personal tragedy.’

‘You said that my brother, Magnus, recommended me to you,’ said Coburg. ‘Do I understand from that, that he knows about the situation?’

Churchill hesitated momentarily, before saying, ‘He knows about the disappearance of the valet, and the fact that something precious to His Majesty is also missing. The people who know about the watch are limited to those of us in this room: His Majesty, me, and you. And we’d like to keep it that way.’

‘I understand that,’ said Coburg. Hesitantly, he asked, ‘There is one exception I would be grateful if you would consider. My detective sergeant, Sergeant Lampson, has shown himself to 27be brave, patriotic and the ultimate in discretion. With your agreement, I would like to share that information with him. He is highly intelligent and has the best nose of any police officer in sniffing out the truth. I can assure you he would not pass on the information about the watch, but if he knew what we were looking for, I believe it would mean we would have a greater chance of recovering it.’

The Prime Minister looked enquiringly at the King. ‘What do you, say, sir?’

The King looked at the two men thoughtfully, then said, ‘I believe we should accept the advice from the chief inspector.’ He looked at Coburg. ‘If you can assure us this will not lead to the story of the watch getting out.’

‘I can assure you of that, sir. Sergeant Lampson would give his life rather than disclose that information.’

‘Very well,’ said Churchill. ‘You may tell this Sergeant Lampson. But no one else.’

‘And who should I report to?’ asked Coburg.

‘To me,’ said Churchill. He looked at the King. ‘Will that be alright, Your Majesty? We both know that you are often out and about on affairs of state, whereas I am usually contactable.’

The King nodded. ‘Yes, that is acceptable.’

‘One last question,’ said Coburg. ‘You told me, sir, that the disappearance of your valet had been reported to the local police. Could you let me have details of the local station it was reported to, and the senior officer who was tasked with looking into it?’

Again, the King nodded. ‘Certainly. I’ll get my secretary to find those details and contacts and messenger them to you at Scotland Yard.’

CHAPTER THREE

On his return to Scotland Yard, Coburg sought out his sergeant in their office, and gestured for him to follow him. Curious, Lampson followed the chief inspector downstairs and then outside into the street.

‘I’ve got something to tell you that’s very private, so we need to be somewhere we can’t be overheard,’ said Coburg. ‘There’s a small public gardens just along the road; we’ll find ourselves a bench there.’

When they got to the small ornamental garden area, Coburg and Lampson found a bench and settled themselves down.

‘I’ve just come from Buckingham Palace,’ Coburg told his sergeant. ‘I was summoned there to meet the King and the Prime Minister.’

‘Blimey,’ said Lampson, impressed. ‘What is it? Are you up for a knighthood or something?’

‘Nothing like that. It seems the King’s valet, a man called Bernard Bothwell, has vanished and they want us to find him.’

‘Why us?’

‘Because of what they say he’s taken, and absolutely no one else is to know about this. At first they didn’t even want me to tell you; it was just supposed to be between me, the King, and Churchill. Luckily, I was able to persuade them that you wouldn’t tell anyone.’29

‘Does that include Eve?’

Eve was Lampson’s wife, who he’d married just a few weeks before.

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘Okay,’ said Lampson. ‘What did this bloke take?’

‘According to them, he took a watch that was given to the King by his father, which makes it special.’

‘A watch?’ said Lampson in disbelief.

‘I don’t believe it either,’ agreed Coburg. ‘I’m sure there’s something else going on that they don’t want mentioned. But we have to go through the paces, looking for this Bernard Bothwell and this mysterious watch. Churchill said “Find the man and you find the watch.” My belief is that it’s the man they want, but they don’t want anyone knowing about it if we find him, and they certainly don’t want anyone knowing what he took from the King, if he took anything.’

Lampson looked concerned. ‘It sounds like we’re getting into murky waters. Are Special Branch involved? Or the intelligence services?’

‘Not according to Churchill, which makes the whole thing even murkier.’

‘So how do we go about it?’

‘The King said he’ll send me the details of Bothwell, and also of the local police station which his wife reported his disappearance to.’

‘So the local police are involved?’

‘But only in the fact the valet’s disappeared, not about this alleged watch. Until those details arrive there’s not a lot we can do, so I suggest we return to the office and see what else we’ve got on our plates.’ 30

‘There’s the Whitechapel murder. And that series of jewel robberies.’

‘Yes. We might have to offload the jewel robberies. I’ve got a feeling this search for the valet is going to be very time-consuming, and as it’s for the King and Churchill, they’ll expect a quick result.’

As Coburg walked into their flat in Piccadilly, Rosa was sitting at the piano playing.

‘That’s nice,’ he said. ‘“Up a Lazy River”. Hoagy Carmichael.’

‘My BBC producer wants that to be the theme song for my Rosa Weeks Presents,’ she told him. ‘If we get a series, that is. This is just a pilot show, as they call it. So I’m making sure I can play it fluently.’

‘Oh yes, you were seeing your producer today. How did it go?’

‘Very good. I’ll tell you all about it later, but first, Magnus phoned for you.’

‘What did he want?’

‘He wants your advice about the East End.’

‘Did he say why?’

‘Something to do with Churchill. He said he’d tell you himself later.’

‘I’d better speak to him and see what’s going on.’

Coburg picked up the receiver and asked the operator to connect him to Magnus’s number. It was Magnus’s old friend and general factotum, Malcolm, who answered.

‘Malcolm, it’s Edgar. Is Magnus there?’

‘Yes he is, Master Edgar.’

A few second later, Magnus was on the phone. 31

‘Rosa tells me you want my advice about the East End,’ said Coburg. ‘Something to do with Churchill.’

‘Yes. Churchill got in touch with me because he’s very concerned about the amount of damage the Luftwaffe is doing to the East End. Apparently the Home Secretary passed him a petition signed by the people of the Stepney area protesting about the lack of proper air raid facilities. By all accounts Whitechapel is one of the worst affected. They seem to be bearing the brunt of the Nazi bombing.’

‘They are,’ agreed Coburg. ‘I was in Whitechapel today and saw the effects for myself.’

‘Churchill is concerned about morale being low there.’

‘It is. The death rate there is worse than almost anywhere else in London.’

‘The thing he’s asked me to do is go to the area and look around, for places that can be quickly converted into air raid facilities. I must admit it’s not an area I know well, so I was hoping you might be able to give me some guidance. I intend to visit the area with Malcolm, but it would help us enormously if you could make suggestions about where we should look.’

‘My advice is to have a word with Sergeant Harker at Whitechapel police station. Joe Harker, that is. He’s a really good man with a comprehensive knowledge of the Whitechapel area. I’d be happy to phone him and tell him you’ll be calling on him.’

‘Would you? That would be enormously helpful, Edgar.’

‘My thought is he’ll also know who it’s best for you to get in touch with about the rest of the area. Stepney, Poplar, Canning Town. And the south side of the river: Bermondsey, Wapping, the Isle of Dogs.’ 32

‘Thank you. That would be excellent. Sergeant Joe Harker at Whitechapel police station, you said.’

‘That’s right. I’ll see if I can get hold of him now. If he’s not at the station, I’ll call him first thing tomorrow morning.’

‘Thank you.’

‘There’s another thing I wanted to talk to you about. I had a meeting today at the palace.’

‘Ah,’ said Magnus, a tone of caution and warning in his voice. ‘I don’t think this is something we should talk about over the telephone.’

‘I agree,’ said Coburg. ‘I was going to ask if I could call on you.’

‘Certainly,’ said Magnus. ‘When?’

‘As you’re in, would it be alright if I came over now?’

‘Could you make it an hour?’ asked Magnus. ‘Malcolm has prepared our evening meal, which is hot, and he’s just putting it on the table.’

‘An hour will be fine,’ said Coburg.

He hung up and Rosa asked, ‘A meeting at the palace?’

‘Yes,’ said Coburg. ‘With no less a person than the King himself.’

‘A gathering of policemen?’ asked Rosa.

‘No, just myself, the King, and Churchill.’

‘My God!’ said Rosa, impressed. ‘You do move in exalted company. What was it about?’

‘Officially I’m not allowed to tell you,’ said Coburg. ‘But because I know my life would be unbearable if I didn’t, I’ll tell you as much as I can, but you are sworn to secrecy. If it gets out that I’ve told you anything, my career will be over and I’ll possibly end up in jail.’ 33

‘I promise,’ said Rosa. ‘No one will hear it from me.’

Coburg told her about his meeting with the King because one of his valets had gone missing, along with a personal item of the King’s that had gone missing at the same time.

‘What sort of personal item?’ asked Rosa.

‘Well, that’s the thing I’m not allowed to tell anyone,’ said Coburg. ‘To be honest, it’s all very strange and I’m not sure if I’m being told the whole truth. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised to find it’s all a red herring. As it is I’m not supposed to even tell you about the valet going missing. If it got out that I’d told you I could well be tried for treason or something.’

‘I promise, not a word about it will cross my lips.’ She thought it over, then asked, ‘If you think there’s something else going on, do you think Magnus might know what it is? He’s close to Churchill.’

‘I don’t know. It seems it was Magnus who recommended to Churchill that I look into what’s happened, but I’m not sure how much he’s been told. As he and Churchill are old comrades, it’s possible Churchill may have told him. But, even if he did, knowing Magnus, his first loyalty is to Churchill and the King.’

‘So this could be a pointless visit.’

‘It could be,’ admitted Coburg. ‘But I like to know what I’m getting myself into. Anyway, that’s my day. You said you’d tell me about your meeting at the BBC. When does your pilot show go out?’

‘Next Tuesday evening. We’re broadcasting from the theatre at the Maida Vale studios.’

‘Can you arrange a seat for me?’

‘I’ll ask Mr Fawcett. He seems very amiable, so I’m sure it’ll be okay.’ 34

‘There’s something else, isn’t there?’ said Coburg. ‘Something that’s bothering you.’

‘That’s the problem with being married to a detective.’ Rosa laughed. ‘I can’t hide things. Yes, it’s the drummer. The music is to be by a trio, me on piano and two old chums of mine, Wally Dawes on drums and Eric Pickup on bass. What with one thing and another, mainly the war, I haven’t seen either of them for a few months. But John Fawcett told me that a while ago Wally was involved in a bombing raid that rattled him.’

‘So, he’s unsteady?’

‘I’m not sure if “unsteady” is the right word. According to Mr Fawcett, Wally drinks. Heavily.’

‘And he wants him replaced?’

‘He does, but he’s agreed to give him a chance. The day after tomorrow we’re going to have a session to go through the music for the show, the three of us with Mr Fawcett, but mainly I think it’s to see how Wally is. How he handles himself.’ She sighed. ‘I hope it goes okay. Wally’s a really nice guy; I’ve always got on well with him and worked well with him.’

‘I suppose you’ll just have to wait and see the day after tomorrow. If he turns out to be falling short, at least you’ll have time to get another drummer.’

‘Yes, but that’s not the point. It’s how it will affect Wally if he gets dropped. It would finish him off.’ She looked at the clock. ‘Anyway, that’s for another day. You’d better get off. Magnus will be waiting.’

‘I will,’ said Coburg. ‘But first I’ll see if Sergeant Joe Harker is still at work.’

Coburg was told that Sergeant Harker had left Whitechapel police station, so he left a message that he’d get in touch with 35him in the morning. He then drove to Magnus’s flat.

Magnus was indeed waiting. For once, he was on his own.

‘As we’re going to be talking about your discussion with the King, Malcolm has tactfully taken himself off for an hour.’

‘We met at the palace,’ said Coburg.

Magnus said nothing, waiting for Coburg to continue.

‘The Prime Minister was there as well.’

‘I imagined he would be.’

‘What’s really going on, Magnus?’

‘What do you mean? I assume they told you His Majesty’s valet has disappeared, and by all accounts he’s taken an item precious to the King, and they’d like you to look into it, with the greatest discretion and without telling anyone else.’

‘Have you been informed of what that item is?’

‘No. Churchill didn’t tell me and I didn’t ask.’

‘And you recommended me to find the valet and the item.’

‘Possibly,’ said Magus guardedly.

‘What do you mean, “possibly”?’

‘Churchill asked me who was the best detective at Scotland Yard, and I told him in my opinion you were. But I got the impression he’d already reached that conclusion. You really do have a good reputation amongst the chattering classes, Edgar. All those cases you’ve solved involving foreign royalty, top diplomats. Even Charles de Gaulle, I’m told. And he’s not the sort to praise anyone English easily. All I will say is to wish you well and hope you can sort this out. The King is a really good man.’

CHAPTER FOUR

Tuesday 1st April

When Coburg and Lampson arrived at their office the next morning, they found a uniformed constable standing outside the door.

‘Apologies for disturbing you, sir,’ said the constable. ‘But Superintendent Allison has asked that Chief Inspector Coburg see him as soon as you arrive.’

‘Thank you, Constable,’ said Coburg, and set off for the superintendent’s office, leaving Lampson to go into their office.

The superintendent was sitting at his desk when Coburg entered his office.

‘You wanted to see me, sir?’

‘Yes.’ Allison reached inside one of the drawers of his desk and took out an envelope, which he handed to Coburg. ‘This came by messenger for you this morning.’

The envelope bore the crest of Buckingham Palace, and was stamped Private and Confidential.

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Coburg.

‘I assume this is a result of your meeting with the King yesterday,’ said Allison.

‘I assume so, sir.’ 37

‘Did the meeting go well?’

‘It seemed to, sir. The Prime Minister was also present.’

‘Just the three of you?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Are you able to tell me what happened at that meeting?’