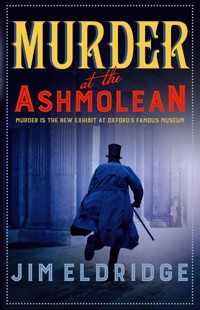

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Museum Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

1895. A senior executive at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is found in his office with a bullet hole between his eyes, a pistol discarded close by. The death has officially been ruled as suicide by local police, but with an apparent lack of motive for such action, the museum's administrator, Gladstone Marriott, suspects foul play. With his cast-iron reputation for shrewdness, formed during his time investigating the case of Jack the Ripper alongside Inspector Abberline, private enquiry agent Daniel Wilson is a natural choice to discreetly explore the situation, ably assisted by his partner, archaeologist-cum-detective Abigail Fenton. Yet their enquiries are hindered from the start by an interfering lone agent from Special Branch, ever secretive and intimidating in his methods. With rumours of political ructions from South Africa, mislaid artefacts and a lost Shakespeare play, Wilson and Fenton soon find themselves tangled in bureaucracy. Making unlikely alliances, the pair face players who live by a different set of rules and will need their intellect and ingenuity to reveal the secrets of the aristocracy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 421

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MURDER AT THE ASHMOLEAN

JIM ELDRIDGE

For Lynne, for ever, as always

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

Oxford, 1895

Daniel Wilson and Abigail Fenton stood in the book-lined office and studied the walnut desk and the empty leather chair behind it.

‘And this is where Mr Everett’s body was discovered?’ Daniel asked Gladstone Marriott.

‘Yes,’ said Marriott. ‘Sitting in that chair, his head thrown back, with a bullet hole in the middle of his forehead. The pistol was on the floor beside the chair. The police believe it fell from his hand after he’d shot himself.’

The three of them were in the office of the recently deceased Gavin Everett, a senior executive at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Daniel and Abigail had travelled to Oxford to investigate the death of Everett after receiving a telegram from Marriott requesting their help.

‘The Ashmolean is possibly the most famous museum in Oxford,’ Abigail had informed Daniel on their train journey from London. ‘It’s also very old.’

‘Older than the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge?’ asked Daniel, referring to the place where the couple had first met.

‘Much older,’ said Abigail. ‘Although it’s only been at its present location in Beaumont Street since 1845, about the same time the Fitzwilliam moved to its current site on Trumpington Street. But the Ashmolean was originally established as a museum in 1683. It’s actually the oldest university museum in the world.’

‘You are a mine of information,’ said Daniel.

Abigail looked again at the wording of the telegram they’d received. Strange death at museum. Your help needed. Please come. Marriott, Ashmolean.

‘He doesn’t mention the name of the dead person,’ said Abigail.

‘He doesn’t need to,’ said Daniel. He handed her the copy of The Times he’d been reading, pointing at a news item.

TRAGIC SUICIDE OF PROMISING MUSEUM CURATOR IN OXFORD

We have received reports of the tragic death by his own hand of one Gavin Everett, a senior executive at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. At this time, details of his death are sketchy, with no apparent reason for him to take his own life, according to the museum’s administrator, Gladstone Marriott.

‘That’s all there is,’ said Daniel.

‘When did it happen?’

‘The day before yesterday.’

‘If it’s a suicide, why has he asked us to look into it? It’s not as if there’s been a crime committed.’

‘Legally, suicide is a crime,’ Daniel reminded her.

‘Yes, but not one where the criminal can be arrested and brought to justice.’

‘I’m sure all will be revealed once we get to Oxford,’ said Daniel.

When they disembarked at Oxford railway station, Daniel began to head towards the line of waiting hansom cabs, but Abigail stopped him.

‘It’s only a short distance to the city centre,’ she said. ‘The walk will do us good after sitting down all the way from London.’

‘Yes, good idea,’ agreed Daniel. ‘It will give me a chance to see these famous university buildings up close.’

‘Later,’ advised Abigail. ‘This way takes us straight to the Ashmolean before we get to the historic colleges.’

‘You should set up as a tour guide,’ commented Daniel as they set off. ‘I’m sure there’s money to be made taking visitors around the university towns and cities.’

‘Thank you, but I have enough to keep me busy,’ replied Abigail.

‘Indeed you have,’ agreed Daniel. ‘An archaeologist and a detective, while I have just the one job.’

‘If you’re looking for flattery from me, you’re wasting your time,’ said Abigail. ‘You already know you are the best at what you do. That’s why people like Gladstone Marriott at the Ashmolean ask for you.’

Daniel smiled. ‘Yes, but I do like to hear you say it.’

‘I’m not sure if that’s because of your vanity, or a lack of confidence in your own abilities,’ commented Abigail.

‘Let me guess: you’re quoting one of these newfangled psychiatrists?’ said Daniel.

‘No, my own observation,’ retorted Abigail. She grinned at him. ‘I’m just using the techniques you’ve taught me about being a detective: study the subject’s demeanour in order to work out their motivation.’

‘So I’m a subject for scientific observation?’ queried Daniel.

‘Of course,’ said Abigail. ‘Admit it, you do it all the time with me, trying to work out whether I’m happy, or upset with something.’ She gestured at a very large white-and-sandstone-coloured building they were nearing on their left. ‘Here we are. The Ashmolean.’

Daniel followed her as she mounted the wide stone steps towards the main entrance.

‘I see the architect has gone for the same kind of columns they’ve got at the front of the Fitzwilliam and the British Museum,’ he noted. ‘Is it some kind of legal requirement that all museums have to look like Roman temples from the outside?’

‘I believe it’s to show that inside is a place of classical education.’

A man in a steward’s uniform was standing just inside the entrance, and Daniel and Abigail approached him.

‘Good afternoon,’ said Daniel. ‘Mr Daniel Wilson and Miss Abigail Fenton, here to see Mr Gladstone Marriott.’

The man’s face broke into a smile.

‘Ah yes! Mr Marriott asked me to keep watch for you and to let him know as soon as you arrived.’ He pointed at the bags Daniel and Abigail each were carrying and offered: ‘Would you like me to have those put in the cloakroom? It’ll be less cumbersome for you while you see Mr Marriott.’

‘Yes, thank you,’ said Daniel.

The man gestured for another uniformed steward who was standing at the foot of a flight of sandstone stairs to join them. ‘George, these are the visitors Mr Marriott has been expecting. Will you take their bags to the cloakroom, and then take over here at the main entrance while I show them to Mr Marriott?’

George nodded and took their bags, leaving Daniel and Abigail free to walk unencumbered up the wide stone steps behind their guide.

‘I’m so glad you’ve arrived,’ said the man. ‘I’m Hugh Thomas, the head steward here at the Ashmolean, and I can tell you this dreadful event has upset us all greatly, and none more so than Mr Marriott.’ He shook his head to show his bewilderment. ‘It was so unlike Mr Everett. But I’m sure Mr Marriott will give you all the details.’

They came to an area at the top of the stairs containing many glass cases laden with a variety of exhibits. Thomas led them past the exhibits and into a short corridor. He stopped at a door, knocked, and at the command from inside of ‘Enter!’, opened the door and announced, ‘Mr Wilson and Miss Fenton have arrived, Mr Marriott.’

Gladstone Marriott, a short, round man in his fifties with a bush of unruly white hair adorning his head, leapt up from behind his desk and came towards them, hand outstretched in greeting.

‘Mr Wilson! Miss Fenton!’

He shook them both by the hand heartily. There was no mistaking the expression of obvious relief on his face. He was smartly dressed in a pinstripe suit of dark material that would have suited a banker, although it was offset by a silk waistcoat in a garish collection of motley colours and ornate, almost oriental, patterns.

‘I’m so glad you could come!’ he said. ‘I’ve heard about the brilliant work you did at both the Fitzwilliam and the British Museum, and I’m hoping you can do the same for us.’

‘I’m not sure what there is for us to do,’ said Abigail. ‘According to the newspaper reports, Mr Everett killed himself.’

‘Yes, that’s the official story,’ said Marriott.

‘But you’re not sure?’ asked Daniel.

Marriott hesitated, then said, ‘Perhaps it would be best if you examined the place where it happened, and hopefully you can come to your own conclusion.’ As he led them along the corridor towards Everett’s office, he informed them, ‘Because we – that is, the Board of Trustees – feel that this might take a day or two, we’ve booked you rooms at the Wilton Hotel. I do hope that’s acceptable to you?’

Daniel shot an enquiring glance at Abigail, who nodded to show she knew the Wilton and it was acceptable to her. Although, Daniel reflected, as Abigail had spent time in tents while on digs in Egypt and elsewhere and seemed happy in his small cold-water terraced house in Camden Town, one of the poorest districts of London, he was sure it would prove acceptable whatever the conditions.

They entered the office of the late Gavin Everett and Marriott showed them the scene of the tragedy: the desk, the chair, the spot where the pistol had been found on the carpet.

‘Was the door locked?’ asked Daniel, spotting the damage to the thick oak door close to the door handle.

Marriott nodded. ‘From the inside. The lock had to be forced in order to gain access. The key was on the floor, just inside the door. Again, the police believe the key fell from the lock onto the carpet when force was used.’

‘So, suicide,’ said Abigail.

‘That is what the police say. However, I have serious doubts, which is why I contacted you.’ He gestured for them to sit in two of the chairs in the room and took the third for himself. Daniel noticed that he avoided seating himself in the leather chair where the body of Everett had been found. ‘Everett had been working here for the past two years, and in that time, I have never known him to show any signs of low spirits or worry. On the contrary, he was a cheerful young man, full of life and always looking for new innovations to improve the museum.’

‘Did he have money worries that you might know of?’ asked Daniel.

‘None!’ said Marriott firmly. ‘He was a single man with no dependents. He had lodgings in a house in Oxford which were comfortable but not ostentatious. I believe he must have had a private income as well as his salary from the museum, because he never seemed to have any concerns about money.’

‘His health?’

‘He was fit and well. He was the kind of man who used to run up a flight of stairs rather than walk up them. He’d never taken a day off for sickness in the time he was here.’

‘How old was he?’

‘In his early thirties.’

‘Local to Oxford?’ asked Abigail.

Marriott shook his head.

‘I believe he came from Bedfordshire originally because he once mentioned having family there. But he’d been a traveller, somewhat of an adventurer, from what I could gather. Just before he joined us at the Ashmolean, he’d spent two years in South Africa, prospecting for gold in the Transvaal.’

‘And was he successful?’

‘I do believe that was where his private income came from, as a result of investments he made following some success in the goldfields.’

‘But not a major success, I would guess, otherwise he’d hardly want to take a job, however worthy.’

‘I must admit that did puzzle me,’ agreed Marriott. ‘But Gavin explained that his mind needed stimulation. He could never just loaf around and rest on the money he’d made in the goldfields. He did say it wasn’t a great deal of money, he told me it was sufficient to support him comfortably, but he wanted a new adventure, and the Ashmolean seemed to supply that. As I hinted, he was a very energetic young man, and certainly his contacts in the Transvaal and Cape Colony have been very useful to us. The material he sourced through them has resulted in our African collection becoming noteworthy.’

‘Did you see him on the day he died?’

‘I did, and that’s another reason why I cannot believe he committed suicide. He came to my office full of excitement and told me he’d had a most unusual proposition which he wanted me to consider.

‘He told me he’d been offered the prologue and first act of an unfinished play by Shakespeare, in Shakespeare’s own hand. The man who offered it to him told him it had come into his hands through a lady – a titled lady. It had been kept, and in great secrecy, according to her, by her husband’s family. His ancestor, an earl in the sixteenth century, being the one who commissioned the play from Shakespeare before he became well known and paid him a small advance. But when Shakespeare was informed his first play was to be performed, and he was getting paid for it, he abandoned the other play – especially as he was told that the earl had run out of money and couldn’t afford to pay for the rest of it.

‘Gavin told me the man had asked for five hundred pounds for the document. He added that he’d asked the man for provenance to prove the authenticity of the piece of work, and the man said he’d be returning with the proof. He’d arranged to see him the evening he died.’

‘What was the proof?’ asked Abigail.

‘Apparently, a letter from the lady herself verifying that the work had come from her husband’s family’s private collection, and its genesis. Under normal circumstances I’d have taken the matter to the keeper of the Ashmolean for guidance, but in the current circumstances …’ And he gave them a look that showed his great concern.

‘I understand,’ said Abigail sympathetically. ‘What was your decision?’

‘I asked him to let me see the documents, and if they seemed genuine, I could see no reason why the museum wouldn’t agree to fund the purchase. As I’m sure you’ll agree, anything by Shakespeare would be a bargain at just five hundred pounds.’

‘Which makes me wonder why the price was so low?’ asked Abigail.

‘The same thought occurred to me,’ said Marriott. ‘According to Gavin, the lady in question was selling the manuscript as … well … to take some sort of revenge against her husband rather than making a lot of money from it.’

‘But was it hers to sell?’ asked Daniel.

‘According to the intermediary, it was. He said she had a letter from her husband to prove it.’

‘I wonder how she’d managed to get such a letter?’ wondered Daniel. ‘And if it was genuine?’

‘That was one of the aspects that Gavin said he’d look into before completing the deal.’ Marriott gave a heavy sigh as he looked at them. ‘You see why I have grave doubts about the idea that Gavin killed himself, with this new project going on.’

‘Did the pistol belong to him?’ asked Daniel.

‘To my knowledge, Gavin never owned a pistol of any sort,’ said Marriott.

‘Do you know at what time Mr Everett was due to meet this intermediary?’ asked Daniel.

‘At six o’clock. The museum closes at five-thirty.’

‘And no one saw this intermediary go into Mr Everett’s office?’

‘No. In fact, we didn’t discover Everett’s body until the next day. When the cleaning staff arrived, his office was locked. Although that wasn’t usual, the staff just assumed he’d locked it for security of something inside.

‘I went to his office soon after I arrived at the Ashmolean because I was keen to discover the outcome of his meeting the previous evening, but found it locked. That was rare, because Gavin was always at the museum by nine, but I thought that perhaps he’d decided to come in late for some reason.

‘When there was still no sign of him by eleven, I sent a messenger to his lodgings to check that all was well with him, but the messenger returned and said that his landlady had seen no sign of him since he left for work the morning before. It was then that I decided to have the door forced.’

‘You felt that something bad might have happened during his meeting with the intermediary?’

‘I did, but I was puzzled why the door should still be locked. Was his visitor locked in there with him? There had been no sounds from the office. Anyway, I got one of the stewards, who also works as a general handyman, to force the lock so that we could gain access, and that was when we found poor Everett.’

‘Who was the police inspector in charge of the investigation?’ asked Daniel.

‘An Inspector Pitt from Oxford Central,’ said Marriott. He frowned, puzzled. ‘It’s odd. At first Inspector Pitt appeared to view the death as suspicious, but then suddenly he announced the official verdict was suicide and declared the case closed.’

‘I’m sure he had his reasons,’ said Daniel. ‘One last thing, Mr Marriott: it would help us enormously to talk to people who Everett was particularly friendly with to get an idea of his life outside work. Was there anyone here at the Ashmolean he confided in, or had a sort of friendship with?’

Marriott frowned thoughtfully, then shook his head.

‘No one in particular,’ he said at last. ‘Now I come to think of it, in spite of the fact that he was always cheerful and friendly to everyone, full of bonhomie, I can’t think of anyone here that he spent time with outside the museum. It might be worth talking to Hugh Thomas, the man who brought you up to my office. He’s our chief steward and he knows most of what goes on with the staff, certainly better than I do. I leave that sort of thing to him while I concentrate on the administrative side.’

CHAPTER TWO

After their meeting with Gladstone Marriott, Daniel and Abigail left the museum and made for a coffee house not far from there, where they could discuss the case away from the very concerned looks of Gladstone Marriott.

‘What do you think?’ asked Daniel as he spooned sugar into his coffee. ‘About this Shakespeare play?’

‘Absolute nonsense,’ said Abigail. ‘If anyone really did have anything of Shakespeare’s, and in his own hand, they’d take it to the Bodleian, not the Ashmolean.’

‘Who or what is the Bodleian?’ asked Daniel.

She stared at him.

‘Surely you’ve heard of Oxford’s famous Bodleian Library?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘As I said on the train, this is my first visit to Oxford, and I know as little about it as I did Cambridge the first time I went there. Except that Oxford is the oldest university in the world.’

‘Second oldest,’ Abigail corrected him.

‘You mean Cambridge is the oldest?’

‘Cambridge is the second oldest in Britain and fourth oldest in the world. The world’s oldest university is Bologna in Italy.’

This time it was Daniel’s turn to stare.

‘How do you know these things?’ he asked.

‘Because it’s what university graduates do, find out about other universities and exchange information. All it means is you and I each have different areas of knowledge. For example, I wouldn’t know how to pick a lock, or understand any of the language most common criminals use, all of which you are very well versed in.’

‘Can we get back to the Bodleian,’ said Daniel. ‘Why would this mysterious person have offered it to them instead of the Ashmolean?’

‘Because the Bodleian is one of the oldest and most respected libraries in the world. It was accumulating books before printing was invented. It already holds copies of Shakespeare’s works. Whereas the Ashmolean is mainly about artefacts: sculptures, pottery, articles of clothing. So, which one would be the natural choice to take this alleged Shakespeare to?’

‘Unless it was too obviously a forgery,’ mused Daniel.

‘Exactly,’ said Abigail. ‘Someone is always claiming they’ve discovered a supposedly lost play or poem of Shakespeare, or other writers such as Chaucer. It’s quite an industry among the literary criminal fraternity. The documents – if they exist – are nearly always faked, and often badly. It will be interesting to actually lay eyes on this alleged Shakespeare and see what standard of forgery it is.’

‘You’re convinced it’s a fake?’

‘If it exists at all,’ said Abigail. ‘So, what’s our next move? Talk to Hugh Thomas and see if he can give us any information about who Everett socialised with?’

‘I think my next move is to pay a call on this Inspector Pitt,’ said Daniel.

‘Without me?’

Daniel smiled. ‘You must have learnt by now that most police forces are notoriously unhappy about private enquiry agents being involved in their area, and they are even more suspicious of women detectives. If not downright hostile. This Inspector Pitt may be the same, in which case I shall be evicted from the police station, but there’s no need for us both to suffer that indignity. If I find that, on the contrary, Inspector Pitt is welcoming then my visit will break the ice for both of us.’

‘You’re being overprotective,’ sniffed Abigail disapprovingly.

‘I can’t see the point of you suffering sarcastic comments and being ejected from a building, if that’s how it might turn out,’ said Daniel. ‘Life’s hard enough without creating unnecessary troubles.’

She smiled. ‘Very well. But I shall be making the acquaintance of this Inspector Pitt at some time or other.’

‘I know you will,’ he said. ‘I’m just trying to make things easier. What will you do? Go to the hotel?’

‘Good heavens, no! I shall go back to the Ashmolean and avail myself of the opportunity to immerse myself in the museum’s wonders. For example, have you ever seen the Alfred Jewel?’ She shook her head. ‘No, that’s a silly question as you haven’t been to Oxford before.’

‘The Alfred Jewel?’ he asked.

‘An ornate piece of jewellery made for Alfred the Great. It’s quite superb, and it’s been one of the Ashmolean’s greatest prizes for two hundred years. So, while you’re having an awkward confrontation with this Inspector Pitt, I shall be rejoicing in the Ashmolean’s treasures.’

‘Yes, that was another thing that came up during our conversation with Mr Marriott,’ said Daniel, puzzled. ‘What was that business about not being able to take the matter to the keeper of the Ashmolean? The “current circumstances” he talked about.’

‘The keeper of the Ashmolean is Arthur Evans, a very distinguished archaeologist,’ explained Abigail. ‘He was appointed in 1884 and he’s done a superb job. Before him the Ashmolean was in a bit of a parlous state; artefacts had been loaned out to other museums, the upper floor was being used for social functions, but Evans reversed all that, brought the artefacts back, instigated a proper collections policy, and returned its academic credibility. Sadly, a couple of years ago, he suffered two terrible tragedies. First his father-in-law, Edward Freeman, died. Freeman was more than just his father-in-law, he was his mentor in so many ways. And then a year later, Evans’ wife, Margaret, Freeman’s eldest daughter, also died while the couple were in Greece.

‘Since that, Evans has stayed abroad, immersing himself in archaeological digs. He’s rarely seen in Oxford any longer, leaving the running of the museum to people like Gladstone Marriott.’

‘So, one tragedy after another,’ mused Daniel. ‘All fatal, and all connected to the Ashmolean. Let’s hope that’s not an omen for us.’

‘The deaths of Edward Freeman and Margaret Evans were from natural causes,’ Abigail pointed out.

‘But not that of Gavin Everett,’ said Daniel. ‘Let’s hope we don’t encounter more deaths before this case is over.’

CHAPTER THREE

Abigail stood before the glass case that housed the Alfred Jewel, rapt. She’d seen the jewel before, but she never failed to feel excited by items such as this, real objects that stretched back in time and gave a solid connection between then and now. It was one of the reasons she’d become an archaeologist, to be able to hold in her hands things that had been wrought hundreds of years before. Or, in her case, with Egyptian, Roman and Greek antiquities being her speciality, many thousands of years. The Alfred Jewel was almost modern when compared to those ancient treasures, having been made, it was believed, in the late ninth century, but that was still a thousand years ago, and the piece itself was exquisite: the image of a man – assumed to be Jesus Christ – made of painted enamel, with the green of his clothes predominant, surrounded by a gold circle, on which the engraved words ‘Aelfred mec heht gewyrcan’ were clear, Old English for ‘Alfred ordered me made’. It had been dug up in 1693 on land in Somerset, Alfred’s old Kingdom of Wessex, and the restoration that had taken place filled Abigail with admiration, to restore something to such original beauty after it had lain for many hundreds of years in soil showed a very special talent.

‘Miss Fenton? Abigail Fenton?’

Abigail, jolted out of her reverie over the jewel, turned and saw a young blonde woman smiling, albeit slightly apprehensively, at her. The young woman held out her hand. ‘Esther Maris. I’m a reporter for the Oxford Messenger.’

‘A woman reporter,’ commented Abigail approvingly, shaking the young woman’s hand. ‘The Oxford Messenger is to be congratulated on its progressiveness.’

‘I heard that you and Mr Daniel Wilson are here to investigate Mr Everett’s death.’

‘We’ve been asked to look into the circumstances,’ replied Abigail guardedly. ‘But at the moment we don’t have anything that’s for publication. We’ve only just arrived.’

‘That doesn’t matter,’ said Esther. ‘I wonder if it would be possible to have an interview with you.’

‘I’m afraid Mr Wilson isn’t here at the moment.’

‘No, I meant an interview with you.’

‘Me?’ said Abigail, surprised.

Esther’s expression took on an apologetic look.

‘When I said I was a reporter, the truth is I’m trying to be one. At the moment they’ve given me the women’s page.’

‘That’s still a step forward from most newspapers,’ said Abigail. ‘Mostly, women tend to be avoided in their pages unless they’re celebrities, murderesses, or political agitators.’

Esther gave an awkward grimace. ‘Yes, and to be honest I only really got this job because my uncle is the proprietor of the newspaper and he persuaded the editor to employ me, and the editor has restricted me to what he calls “women’s issues”. But I intend to prove to him that I can be a proper journalist, so I’m using my column to expand what most people think of as “women’s issues”. For example, you. A woman detective!’

‘I’m not sure if it’s accurate to describe me as a detective,’ said Abigail doubtfully. ‘I work with Mr Wilson, who is a former detective with Scotland Yard, and I’m learning from him. So, I suppose you could call me a trainee.’

‘In the same way that you could call me a trainee journalist,’ said Esther enthusiastically. ‘Please, my readers would love to hear about you. Can we talk? I promise I’ll let you see what I write before I put my copy in.’

‘Very well,’ said Abigail. She looked towards an attendant, who was glaring at the two women with an expression of disapproval. ‘But somewhere else. I don’t think the Ashmolean would approve of us disturbing the rather reverential air here with a stream of chatter.’

‘Why don’t we go to the Randolph Hotel across the road,’ suggested Esther. ‘They do a lovely afternoon tea there. And the Oxford Messenger will foot the bill.’

Daniel had made his way to Oxford’s central police station at Kemp Hall, an ancient timbered building from days long gone by, possibly Elizabethan to Daniel’s eye. It was set in a yard just to the south of the high street. He was told that Inspector Pitt was on site and was escorted by a uniformed constable to a small office at the back of the police station, where Inspector Pitt was sitting at his desk, studying some papers. Pitt looked up unsmiling and wary at Daniel as he entered the office.

‘Good afternoon, Inspector. My name’s Daniel Wilson and I’m a private enquiry agent. Out of courtesy, I’ve come to let you know that Miss Abigail Fenton and I have been asked by the Ashmolean to look into the events surrounding the death of Mr Everett there.’

‘It’s suicide,’ said Pitt curtly.

‘I know,’ said Daniel. ‘We’ve been asked to look into why he may have committed suicide, in case there might be any adverse reflection on the Ashmolean.’

The inspector studied Daniel thoughtfully for a moment, then he said, ‘You were one of Abberline’s crew.’

‘I was,’ said Daniel. ‘But that was some time ago. I left the force shortly after he did.’

‘Your name came up when I was talking to one of your old colleagues recently. John Feather of the Met.’

Daniel’s face broke into a smile.

‘John! How is he? I haven’t seen him …’

‘Since that business at the British Museum,’ finished Pitt. ‘Yes, he told me about that. And how you never got the credit for cracking the case. You and your partner, this Miss Fenton.’

‘Credit would be nice, but that’s not why we do it,’ said Daniel. ‘John’s a great detective, and an even better person.’

‘Yes, he said the same about you,’ said Pitt. He cast a look around to make sure they weren’t being overheard, then got to his feet and said in almost a whisper, ‘That’s why I’m going to tell you something.’ He jerked his head towards the door. ‘Let’s go out the back. Less chance of wagging ears.’

Intrigued, Daniel followed the inspector out of his office, down a corridor, and then through a door and into a cobbled courtyard that smelt strongly of horse manure.

‘The stables,’ said Pitt.

Daniel smiled and gave a sniff. ‘Yes. I picked up the clue.’

A row of four half-doors ran along one side of the yard. All were shut, so Daniel assumed the horses were out.

‘This Everett business,’ said Pitt. ‘I didn’t like it, and I said so to my guv’nor, Superintendent Clare. For one thing there were no powder marks around the wound, and if the pistol had been fired with the end against his forehead, you’d have expected powder marks at least.’

‘So, the indication was that the shot came from a longer distance.’

‘That was my thinking.’

‘And the business of the door being locked?’

‘Did you examine the door?’

‘Yes. There was space at the bottom for a key to be pushed under it.’

‘Exactly. The way I see it, someone aims a pistol at Everett and shoots him in the forehead, then drops the pistol by his hand. They go out, lock the door from the outside, then push the key under the door back into the room so that when the door’s opened it looks as if the key fell out of the lock.’

‘How did your super react when you told him this?’

‘At first he was all for starting an investigation. And then the telegram arrived. “No investigation into Everett death. Suicide.” The super showed it to me, but with strict instructions not to say anything to anyone else. I’m only telling you based on what John Feather told me about you, and to warn you that if you carry on with this you’ll be moving into dangerous territory.’

‘Who was the telegram from?’

‘The War Office.’

Daniel frowned. ‘The War Office? What would they have to do with an executive of a museum in Oxford?’

‘It suggests to me he was more than just that.’

‘Was he ever involved with the military? In the armed forces, for example?’

‘Not that we could discover.’

‘Did Superintendent Clare question the instructions in the telegram?’

Pitt shook his head. ‘The super’s a good bloke, but like all supers I’ve ever known, he doesn’t like to upset the powers that be. So, officially, that’s it. But remember what I said: I haven’t said anything to you about the case, and especially not about the telegram.’ He saw the look of doubt darken Daniel’s face, and asked, ‘Is that a problem?’

‘No,’ said Daniel hesitantly, ‘but I don’t feel comfortable about keeping that from Gladstone Marriott at the Ashmolean. They’re the ones paying us, and we’re supposed to keep him informed. And, of course, there’s my partner, Miss Fenton.’

Pitt deliberated on this for a brief moment, then nodded.

‘Understood,’ he said. ‘Your partner, yes. But as far as the Ashmolean is concerned, can I ask you to only keep it to Marriott? And to persuade him to keep this to himself. If it gets out, the super will know it came from me, and he’s a good bloke. I don’t want him to feel I’ve let him down.’

‘Trust me,’ Daniel promised him. ‘Miss Fenton and Mr Marriott, and no further. And I’ll impress on Marriott the need to keep it to himself, and no one else.’

Abigail and Esther sat in the elegant tea room in the opulent surroundings of the Randolph Hotel. Abigail had been here before when visiting a friend in Oxford. It seemed to her that the Randolph was where people brought other people to impress them. Was that the case here with Esther Maris? If so, Abigail had been tempted to tell the young woman it wasn’t necessary; for Abigail it was people who impressed her, or didn’t, not their surroundings. But she had to admit, the pastries they served at the Randolph were particularly good.

‘I’ve been doing some research into you and Mr Wilson, and I learnt that you used to be an archaeologist before you became a detective,’ said Esther.

‘I still am an archaeologist,’ said Abigail. ‘Mr Wilson brings me into the detective work when there might be a historical aspect.’

‘I found some articles you wrote about your work in Egypt, unearthing ancient relics at the site of the pyramids. How hard was that for you as a woman? Mostly it seems that sort of archaeology is done by men.’

‘In fact, there are quite a few women archaeologists, but most prominence is given to men because they tend to lead the expeditions. I suppose I’m unusual in that I also write articles about the digs, and in that aspect, I’ve been fortunate in the fact that the men who led the expeditions and digs I’ve been on encouraged me to do that.’

‘You were involved in digs in Egypt and Mesopotamia, and Greece and Turkey. Were there any problems for you as a woman while you were there?’

‘No, I was accepted by the locals as a person doing a job. Don’t forget, there have been many other women doing such work before me. Hester Stanhope, for example, who in the last century was the first to carry out an archaeological dig in the Holy Land.’

‘You got your degree in history at Cambridge, didn’t you? At Girton?’

‘You have been doing your homework,’ Abigail complimented her.

‘Again, that’s unusual for a woman.’

‘Not that unusual,’ said Abigail. ‘Here at Oxford you have Somerville College, which is a women’s college. I accept these may be early days in society accepting that women deserve an equal education to men, but Girton and Somerville are just the start.’

‘But has your success been at the expense of romance?’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Abigail, warily.

‘Most women expect to fall in love and marry and have children—’

‘No. Society expects women to marry and have children,’ Abigail interrupted her. ‘Women have a choice.’

‘But how about you? Do you want to marry and have children?’

Abigail hesitated.

‘At the moment it’s not something I’m thinking about,’ she said.

‘So you’re putting your career before romance?’

‘Would you ask that same question of a man?’ queried Abigail. ‘A politician? A man archaeologist? A male detective?’

‘Yes, but it’s different, isn’t it,’ insisted Esther.

‘Only because society considers it to be,’ said Abigail. ‘And I would point out that we have a woman on the throne as Queen. And not just Queen, but Empress of the British Empire, which covers a third of the world’s population. Yet it hasn’t stopped her marrying and having children.’

There’d been something evasive about Abigail Fenton, Esther decided as she left the Randolph. It had happened when Esther had asked about romance. From her experience, most women she’d interviewed had either waxed lyrical about their other half or laughed and said they were just waiting for Mr Right to appear. Abigail Fenton had done neither. So – was there a romance in her life? If so, who? Could it be this Daniel Wilson? She certainly seemed to have formed some kind of partnership with him. And as far as she’d been able to find out, Daniel Wilson was a single man. That made them ideal for a coupling. Even though their social backgrounds were so different.

Or was Abigail Fenton being defensive because there was something else happening romantically, something less orthodox? Esther thought of some of the women she’d met who’d been at university and had thrown themselves into a society of brilliant – and single – women, often to the exclusion of men. Quite a few of them had been quite masculine in their attitudes, although not all of them in appearance. There had been quite a few who were very attractive, but who seemed to reserve their favours for their own sex. Was that what Abigail Fenton was hiding, that her thoughts of romance were for other women, not for men?

But Esther had to admit that if that was so, there’d been no hint of it during their conversation. No lingering looks from her. Instead, Fenton had been … careful. Secretive. What was she hiding? Whatever it was, it would certainly add spice to the story she was planning. The sudden death of a prominent executive of the Ashmolean, alleged to be suicide, although there seemed to be no reason why he would take his own life. She smiled to herself. More secrets to be uncovered. This could be the story that finally saw her throw off the ‘women’s page’ tag.

CHAPTER FOUR

Abigail was crossing the street from the Randolph to the Ashmolean when she saw Daniel approaching from the other direction.

‘Well?’ she demanded. ‘Did you get thrown out of the police station?’

‘No,’ Daniel told her. ‘In fact, Inspector Pitt was very welcoming. And he also gave me some information which confirms Mr Marriott’s suspicions about Gavin Everett’s death.’

‘It was murder?’ asked Abigail.

‘Definitely,’ said Daniel.

Briefly, he filled her in on what Pitt had told him, then said, ‘So now we take this to Mr Marriott. Though we wait to see whether he’ll be pleased at the revelation that his suspicions were correct, or more worried as a result.’

They headed up the stairs to Marriott’s office, where Daniel made his report.

‘It now transpires that the police still believe that Mr Everett was murdered, and his death made to look like suicide.’

‘But they told me that they were viewing it as suicide, and the case was closed,’ said Marriott.

‘Because they were instructed to do so by certain political powers in government.’

Marriott stared at them. ‘The police told you this?’

‘In confidence,’ said Daniel. ‘The information is not to be revealed. In fact, they were reluctant to admit it to me and only did so because of certain contacts I still have inside Scotland Yard. But they have insisted it must remain a secret. As far as the public are concerned, and everyone here, Gavin Everett committed suicide. So, officially, Miss Fenton and I will be looking for reasons why he took such an action. But in reality, that will mean us trying to find out who murdered him, and why. Providing you agree to us continuing with our investigation, of course.’

‘Most certainly!’ said Marriott. ‘My concern is that what happened to Everett could happen to any one of us here at the Ashmolean.’

‘Depending on the motive,’ said Daniel. ‘We may find his death was nothing to do with the museum, but for more personal reasons.’ He frowned, and added thoughtfully, ‘Although, from what I picked up from the police – and this is in the strictest confidence and mustn’t be repeated outside this room …’

‘I understand,’ said Marriott.

‘The fact that the investigation was halted due to intervention by a senior government official in London suggests there may well be a political motive.’

‘But Everett wasn’t involved in politics!’ burst out Marriott.

‘So, we are investigating a murder which may have political associations,’ said Abigail as they left Marriott’s office.

‘It may indeed,’ said Daniel. ‘Although, according to Marriott, that seems unlikely. For my part, it seems a great coincidence that he’s killed while supposedly having this meeting to talk about this piece by Shakespeare.’

‘Alleged piece by Shakespeare,’ Abigail corrected him. ‘If such a work does exist, and if the story about it being in this mysterious titled woman’s family is true, then if her husband found out that she planned to sell it, one way to stop that would be to kill Everett.’

‘Simpler, surely, to kill his wife,’ said Daniel.

‘Yes, true,’ admitted Abigail. ‘Perhaps he already has. Perhaps some aristocratic establishment in Oxford is currently holding a wake for the recently deceased lady of the house.’

‘The whole thing could be a dead end,’ said Daniel. ‘The story may be true, someone may have offered it for sale to Everett, but it may be nothing to do with his death. And the only way we can decide is by finding out who the titled lady is, and the identity of her husband, and then dig into that situation.’

‘That’s not going to be easy,’ said Abigail. ‘The aristocracy can be very protective of their reputations; most of them have had long experience in hiding unpleasant family secrets.’

‘So, the weak link here is the intermediary who Everett was dealing with. If we can find out who that was, that’s our way in. Which means our first thought about finding out who Everett was known to be associated with, either through business dealings, or socially, was the right one. Because, as you rightly pointed out, if someone really had a genuine Shakespeare piece to sell, they’d take it to the Bodleian. Or, if not the Bodleian, to one of the very many literary scholars in Oxford. If they brought it to Everett, it’s because they knew him personally.’

‘So, it’s back to finding out who Everett was particularly friendly with,’ said Abigail.

‘Which is why we are going to talk to Hugh Thomas and see what he can tell us,’ said Daniel.

Unfortunately for them, the head steward wasn’t able to offer any clues as to who Everett’s close friends had been, either inside the museum or outside.

‘He was always very friendly, not stuck-up or patronising at all, not like some people would be in his position. Always a good word for everybody. But as for forming any particular friendships, I must admit I can’t think of any.’

They received the same response from everyone else they spoke to at the museum; everyone liked him, but no one was particularly close to him. No one socialised with him outside of work, and no one knew of any social circle he might have been involved with.

‘In short,’ summed up Daniel as they carried their luggage to the nearby Wilton Hotel, ‘we have a good-natured chap who, despite being very friendly to everyone, actually keeps himself to himself. Frankly, a bit of an enigma.’

‘A mystery to unravel,’ agreed Abigail.

At the hotel, they were shown to their adjoining rooms, and once the porter had left, they both went into Abigail’s room.

‘This will do for us,’ announced Abigail. ‘It has a better view. But the idea that we have to have separate rooms at all is ridiculous!’

‘We’re not married,’ said Daniel. ‘The hotel has a reputation to maintain.’

‘That’s nonsense!’ said Abigail. ‘I bet there are many men staying here with women who aren’t their wives, and the hotel knows it but turns a blind eye.’

‘That may well be true, but our stay here is being paid for by the Ashmolean, and they have booked us a room each, because we are two single people, a man and a woman. They haven’t asked about our living arrangements, and we haven’t told them we live together. We can confront the issue and tell everyone – the Ashmolean, the hotel – that we are a couple and insist on sharing a room, but if we do that, I’m sure that certain people will raise the question of morality with the Ashmolean, the hotel, and potential future clients of ours. Or we can do what everyone else does, play out the charade of having two rooms while we only use the one, and rumple the bedclothes of the one in the room we’re not using to pretend we’re occupying both.’

‘It’s so hypocritical!’ groaned Abigail.

‘I agree,’ said Daniel. ‘We could always get married, of course. You said you’d marry me.’

‘And I will. When the time is right.’

‘When I’m old and grey?’ asked Daniel with a smile.

CHAPTER FIVE

Next morning, their first call was to Everett’s lodgings.

‘Hopefully we’ll find out from his landlady the names of his friends outside of work,’ said Daniel. ‘Or at least what sort of social life he led.’

Mrs Persimmons was a tall, austere-looking woman, who regarded them with suspicion until they explained the reason for their call.

‘We’re here on behalf of the Ashmolean,’ Daniel explained. ‘We’re trying to find out why your lodger, Mr Everett, tragically did what he did, and to that extent it would help us enormously if we could find out as much as we can about his life outside of the museum.’

‘He was a lovely man! An absolute gentleman!’ Mrs Persimmons told them.

‘So we have been told, but in order to understand what happened we need to find out what was going on in his life. Did he express to you any worries he may have had, for example?’

She shook her head. ‘Absolutely not. In fact, he was the perfect tenant. He kept himself to himself, never interfered with the rest of the house, and was always prompt with his rent.’

‘Do you have any other lodgers?’ asked Abigail.

‘No, Mr Everett was the only one,’ said Mrs Persimmons. ‘One’s enough for me. I can only hope the tenant I get to replace him will be as considerate.’

‘What sort of people did he socialise with?’ asked Daniel.

‘That’s difficult to say, sir. He didn’t socialise with them here. He knew how careful I am keeping my house neat and tidy. Mr Everett was no problem at all, but some young gentlemen I’ve had before have been known to have untidy habits, especially when drink’s been taken.’

‘Was Mr Everett a great drinker?’

‘Good heavens, no! In fact, I never saw him touch a drop. I thought at one time he might be temperance, or one of them sort, but I never heard of him attending any sort of meetings like that.’

‘What about women friends?’ asked Abigail.

Mrs Persimmons looked at her, shocked.

‘There was nothing of that sort!’ she said firmly. ‘I run a decent house!’

‘I meant women – or men – he may have seen relatively frequently. Not necessarily here, but …’

‘In which case I wouldn’t know anything about it,’ said Mrs Persimmons curtly. ‘I don’t pry into people’s private affairs. And neither should other people, either.’

‘But Mr Everett has died by his own hand …’ insisted Abigail.

‘And in my opinion, he should be left to rest in peace,’ said Mrs Persimmons, looking more indignant. ‘I’ve said what I had to say. He was a decent man who never gave me a moment’s trouble and I’m sorry to lose him. And now, I’ll thank you to let me get on.’

With that she closed the door.

‘I don’t think I have your skill in charming people,’ sighed Abigail as they walked away.

‘I think we learnt enough to know that whatever kind of life Mr Everett lived, it wasn’t at Mrs Persimmons’ house,’ said Daniel.

‘Nor, by all accounts, did it include anyone at the Ashmolean,’ said Abigail. ‘Don’t you find that strange?’ She looked questioningly at Daniel. ‘Where to now?’

‘I think,’ said Daniel, ‘it’s time you made the acquaintance of Inspector Pitt.’

Inspector Pitt’s face broke into a welcoming smile as Daniel ushered Abigail into his small office.

‘Miss Fenton!’ he said, coming from behind his desk and holding out his hand to shake hers. ‘It’s a pleasure to meet you! Especially after I’ve heard such good things about you.’

Abigail shot an amused glance towards Daniel.

‘You don’t need to believe everything that Mr Wilson tells you,’ she said.

‘Not Mr Wilson, Inspector Feather at Scotland Yard. I met him at a conference recently, and your names came up about the recent case at the British Museum. Do I take it that you specialise in cases where murders occur in well-known museums?’

‘I hope not,’ said Abigail. ‘It makes me sound like a harbinger of doom, and if word gets around some museums will view my arrival with trepidation and wondering who will die next.’

‘Miss Fenton is the historical expert of our team,’ explained Daniel.

‘Yes, so John Feather said. He outlined your career as an archaeologist. I must say, it sounds more exciting than detective work.’

‘The locations may be less exotic, but the work can be a lot more interesting,’ said Abigail.

Pitt lifted a pile of papers off a chair and gestured for Abigail to sit.