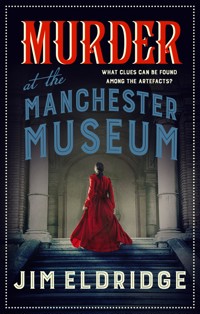

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Museum Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

1895. Former Scotland Yard detective Daniel Wilson, famous for working the notorious Jack the Ripper case, and his archaeologist sidekick Abigail Fenton are summoned to investigate the murder of a young woman at the Manchester Museum. Though staff remember the woman as a recent and regular visitor, no one appears to know her and she has no possessions from which to identify her. When the pair arrive, the case turns more deadly when the body of a second woman is discovered hidden in the depths of the museum. Seeking help from a local journalist, Daniel hopes to unravel this mystery, but the journey to the truth is fraught with obstacles and the mistakes of the past will not be forgotten ...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

MURDER AT THE MANCHESTER MUSEUM

JIM ELDRIDGE

5

To Lynne, for ever

6

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

1895

‘Crewe next stop!’ called the train conductor. He then began to list the various stops after Crewe the train still had to make before it reached Manchester, before adding in ringing tones, ‘For all other destinations, change at Crewe!’

Daniel Wilson studied the telegram he and Abigail had received the day before.

‘Murder at Manchester Museum. Please come urgently. Bernard Steggles, Director,’ he read, then folded it and put it back in his pocket with a weary sigh. ‘But who’s been murdered? When? And how?’ asked Daniel. ‘There’s been nothing about a recent murder at the Manchester Museum in the newspapers.’

‘Because they’re the London papers,’ Abigail pointed out, turning a page in her magazine.

‘But they carry news from further afield,’ said Daniel. He 8tapped the copy of The Times that lay on his lap. ‘There are stories in here from Glasgow, Newcastle, Paris and Berlin. But nothing concerning Manchester.’

‘Which suggests whoever was murdered was not seen as an important figure.’

‘So why bring us all the way from London when they have a perfectly adequate police force capable of investigating a local crime?’

‘Do you know much about the Manchester police force?’

‘No,’ admitted Daniel.

‘It’s a pity the telephone service hasn’t yet been connected nationally, otherwise you’d have been able to talk to Mr Steggles and got the answers you wanted.’

‘The telephone?’ repeated Daniel with a frown.

‘Yes,’ said Abigail. She held the copy of the Museum Digest she’d been reading towards him. ‘It says here—’

The scream of a woman in terror from the corridor cut through the rattling background chug-chug of the train. Immediately, Daniel was out of his seat, had pulled the door of their compartment open and was in the corridor, Abigail close behind him.

A middle-aged man was at the end of the corridor, holding a young woman viciously by her hair. In his other hand he held a knife, which he was pointing at the two uniformed railwaymen, a guard and the conductor, who stood watching the pair nervously.

‘Leave us alone!’ shouted the man. ‘It’s not your business.’

The man was drunk, realised Daniel. Not drunk enough to be easily overpowered, but drunk enough to do something dangerous. Like stab someone. And the young woman he was holding tightly on to looked the most likely victim. The man was short but stocky, his jacket barely able to contain his muscular upper body. The young woman was wearing a skirt and short-sleeved blouse. There 9was no sign of a coat or a bag or other outer garments. Daniel guessed they must have been left behind by the woman when she fled the compartment.

‘Sir …’ began the guard uncomfortably.

‘Go away!’ yelled the man. ‘This whore took my wallet. I want it back!’

‘I never!’ sobbed the woman. ‘He must have dropped it!’

‘Dropped it?’ sneered the man, adding vengefully, ‘I’ll drop you, you whore!’

And he slashed at her, the blade opening a wound in her upper arm that sprayed blood towards the two railwaymen, who hurriedly pressed back as far as the corridor would allow them to as the woman screamed.

Daniel moved. He took his wallet from his pocket and threw it at the man’s face. Instinctively, the man let go of the woman and threw his hand up to protect himself. As he did so, Daniel chopped down hard on the wrist of the hand that held the knife with the edge of his right hand, at the same time following it with a hard left hook that smashed into the man’s face, sending him crashing backwards into the wall of the corridor. The man crumpled as he and the knife fell to the floor. Daniel put his foot on the knife and kicked it away to a safe position, but the fact the fallen man hadn’t moved showed the danger was over.

Abigail went to the terrified and sobbing young woman, taking a large handkerchief from her pocket, and placed it against the knife wound, staunching the flow of blood.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘If you come to our compartment I can clean and bandage that.’

The guard stepped forward, his face grim.

‘I’m afraid that won’t be possible, madam,’ he said. ‘This man accused her of stealing his wallet. This is now a police matter. We 10have to take her into custody and hand her to the police when we reach Crewe.’

‘In that case you can have her once I’ve dealt with her wound, and not before,’ snapped Abigail.

As Abigail led the young woman to their compartment, Daniel gestured at the fallen man and the knife.

‘I’d advise you to secure his hands in case he tries anything else when he comes round,’ he said to the two railway officials.

‘Thank you, sir, I’d already thought of that,’ said the guard curtly. ‘Everything was under control before you intervened.’

Daniel nodded and headed back to their compartment, where he found Abigail cleaning the wound. Once she was sure there was no chance of infection, she took a small bandage from her bag and proceeded to bind it around the woman’s upper arm.

‘It might need stitches,’ said Abigail. ‘Unfortunately, the needle I carry in my sewing kit is only suitable for cloth.’ She looked at the conductor, who had appeared in the doorway of the compartment and was studying the scene with a look of some discomfort on his face.

‘I hope you have more compassion than your oaf of a colleague,’ she said. ‘When you hand this young lady to the police, inform them that she will require stitches in the wound.’ She fixed him with a steely glare. ‘I shall check with the railway company later to make sure my instructions were carried out. If I find they weren’t, I shall report you to your superiors.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’ The conductor gulped nervously. ‘They will be.’ His tone changed to one of officialdom as he turned his attention to the young woman. ‘I must ask you to come with me, miss.’

Daniel followed the young woman into the corridor as the conductor took her gently by the elbow and escorted her along the corridor to the guard’s quarters. The man that Daniel had hit 11still lay on the floor, and although he was conscious, he was firmly secured by a rope at the wrist and ankles with the guard standing over him.

Daniel returned to the compartment and pulled the door shut.

‘All’s well that ends well,’ he said. ‘Well done for the swift way you acted on treating her knife wound.’

‘It wasn’t as vital as the way you acted in disarming him,’ said Abigail. She gave an angry snort of derision. ‘I heard what the guard said to you. “Everything’s under control.” Ha! Lunacy! And not a word of thanks!’

‘You can’t please everyone,’ said Daniel wryly.

‘He might have killed that woman. And the guard and conductor!’

‘It’s all sorted out now,’ said Daniel. He looked at her inquisitively. ‘You were talking about telephones before all that.’

Abigail stared at him in amazement. ‘You’ve just saved a woman’s life, overpowered a dangerous knife-wielding maniac, and you want to talk about telephones?’

‘I’m interested,’ he said. ‘They say that the telephone is going to be the thing of the future. That there are already plans to put in telephone lines that will link Europe and America, and even Australia. Imagine, being able to talk to someone at the other side of the world without leaving your house!’ He nodded towards the Museum Digest on the seat beside Abigail. ‘You were about to read me something before the trouble began.’

‘Yes,’ said Abigail. She opened the magazine and began to flick through the pages. ‘Last night, when you said we were going to Manchester, I decided to look through some of the recent editions to see if there was anything in any of them about the Manchester Museum, and I found this article. Ah yes, here it is.’ She began to read. ‘The museum in Manchester is among the latest to subscribe to the newly installed telephone exchange in that city. It is believed 12the number of subscribers has now passed seven hundred, many of them private customers. This means that people as far apart as Stockport, Oldham and Bolton can now communicate with one another through the telephone system, making Manchester the first city in England to have a fully operational telephone exchange, with plans to extend the lines to Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield, and even as far as Birmingham.’

‘But not to London,’ observed Daniel.

‘That day will come, if the rest of the report is to be believed,’ said Abigail. She offered the magazine to Daniel. ‘Would you like to read the rest of it?’

Daniel was about to take it, when they heard the conductor’s shout of: ‘Crewe station! Crewe station!’

‘Later,’ he said, passing the magazine back to Abigail. ‘I’ve been told that Crewe is one of the busiest junctions on the whole network, and if that’s so then I feel this compartment might suddenly become rather crowded and we’ll be spending most of our time stopping our comfort being encroached on by hordes of travellers bound for Manchester.’

‘Don’t worry.’ Abigail smiled. ‘I’ll protect you. If anyone tries to sit on you, I’ll deal with them.’

CHAPTER TWO

As it turned out, although other travellers joined them in the compartment, it did not turn out to be the free-for-all that Daniel had envisaged, just three apparently respectable businessmen and a husband and wife. When Daniel had sometimes taken a train in central London, especially one travelling east towards Southend, he’d often found himself besieged by families with numerous children of all ages who seemed to only want to fight with one another and generally cause mayhem, while their parents sat seemingly oblivious to the distress their offspring were causing the other passengers. The quiet mood of their fellow passengers meant that Daniel was able to take time to read about the Manchester Museum in Abigail’s magazine. As a result he learnt that, as well as the museum enjoying telephone access in the area of Manchester and surrounding cities, the museum was a relatively recent establishment. Although it 14incorporated material from the earlier collections of the Manchester Natural History and Geological Societies, the newly designed building that housed the Manchester Museum had only been opened to the public seven years before, in 1888. The article highlighted the large number of mounted animals on display, many of them from someone called Brian Houghton Hodgson, who seemed to have discovered many species during his travels in India and Nepal which had been previously unknown to the West. The museum also seemed to have one of the largest collections of beetles and other insects outside of London’s Natural History Museum.

‘Not much here about your particular area of expertise,’ commented Daniel, referring to Abigail’s reputation as one of Europe’s leading Egyptologists, a reputation based on her archaeological work at the pyramids in Egypt, as well as her explorations of ancient temples in Greece and of Roman sites.

‘It is expanding,’ she said. She laid her finger on a paragraph. ‘You’ll see it mentions new finds being brought in from the excavations at Gurob and Kahun, as well as from Flinders Petrie.’ She gave a smile of reminiscence as she added, ‘I worked with him, you know.’

‘Who?’

‘Flinders Petrie.’

‘In Egypt?’

‘Yes, at Hawara in 1888. Then again in Palestine at Tell el-Hesi. 1890.’

‘What was he like?’ asked Daniel.

‘Much the same as he still is today. A big bear of a man. It’s astonishing to think that he’s still so comparatively young for an archaeologist and he’s achieved so much! He was in his late thirties then. In his early days the archaeological establishment considered him a bit of a maverick. He didn’t always stick to 15the rules. For example, when he began the dig at Tanis in the New Kingdom site he took on the role of foreman in charge of the workers himself. He said it was one less level of bureaucracy which would otherwise slow things down.’

‘Attractive?’

Abigail laughed. ‘Very.’ Then, with a glance at the other passengers, she whispered to him, ‘But you have nothing to fear on that aspect. It was purely a meeting of two minds with one aim.’

On their arrival at the main London Road station they elected to walk to Oxford Road, where the museum was situated, rather than take a hansom. His years as a police officer had led Daniel to believe that the best way to see any new city was on foot, and he was fortunate that Abigail, with her many experiences exploring exotic towns and cities, was of the same opinion. The museum was a large, rather ornate building.

‘It looks like a slightly smaller version of the Natural History Museum in London,’ observed Daniel.

‘It was designed by the same architect,’ said Abigail. ‘Alfred Waterhouse. But don’t say anything to them about it being slightly smaller. Museums can be very sensitive about unfavourable comparisons.’

‘I wasn’t being unfavourable,’ defended Daniel. ‘I just said it looked slightly smaller.’

‘But it may not be inside,’ said Abigail. ‘Sensitivity is all. We don’t want to get off on the wrong foot with our new client.’

‘Perhaps if I say it looks larger?’ suggested Daniel.

‘Better not to say anything,’ advised Abigail.

Inside, they found a uniformed commissionaire on duty at the door and asked him for directions to the office of Mr Steggles, the museum’s director.16

‘Would you be Mr Wilson and Miss Fenton?’ asked the commissionaire.

‘We are,’ confirmed Daniel.

‘Mr Steggles asked me to watch out for you. If you’ll follow me I’ll take you to his office.’

The commissionaire summoned a similarly uniformed man from inside the museum and indicated for him to take over on duty at the main entrance, then led the way to a narrow stone staircase to one side of the entrance doors. Daniel and Abigail followed him, carrying their overnight bags, and soon they were standing outside a dark oak door on the first floor. The commissionaire knocked at the door, then opened it and announced, ‘Mr Wilson and Miss Fenton, Mr Steggles.’

‘Thank heavens!’ said a cultured voice from within. The door was thrown wider and Daniel and Abigail beheld a small, thin man in his fifties dressed in a close-fitting soberly dark suit. With his neatly trimmed hair and tiny moustache, he reminded Daniel of a senior bank clerk rather than the man in overall charge of a large and important museum.

‘Do come in!’ said Steggles. He led them across the plush, thickly piled carpet to two chairs waiting by his large desk. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he apologised as they put their luggage down. ‘I should have thought and suggested you go to the hotel we’ve booked you into first before you came here, but I’ve been so worried over what happened that the distraction has played havoc with some of my thought processes.’

‘What has happened?’ asked Daniel, as he and Abigail seated themselves. ‘Your telegram just said a murder had been committed here at the museum.’

‘It’s now two murders,’ said Steggles grimly.

‘Two?’

‘The first we discovered on the day it happened. The 17second only manifested itself this morning.’ He looked at them apologetically. ‘I’m forgetting my manners and common courtesy,’ he said. ‘Can I order tea for you? Or anything else?’

‘Tea would be perfect, thank you,’ said Abigail.

Steggles pressed a button on a large black machine on his desk, at the same time lifting what looked like a small metal speaker from it, which was connected to the machine by a length of wire. A woman’s voice came from the black machine.

‘Yes, Mr Steggles?’

‘Tea for three, please, Mrs Wedburn. With biscuits.’

‘Certainly, Mr Steggles.’

As Steggles replaced the metal speaker on the machine, Daniel commented, ‘We were reading about the telephone system here in Manchester.’

‘Ah, this isn’t that system,’ said Steggles. ‘It’s a variation. Internal only. It uses similar technology, but it doesn’t have to go through an operator as it’s only connected to my secretary in her office.’ He smiled. ‘It saves me having to walk along there if I have something to tell her about.’

‘The murders?’ prompted Daniel gently.

‘Yes,’ said Steggles. ‘On Thursday last week, four days ago, a young woman was stabbed to death here in the museum. She’d been sitting at a table in the reading room, apparently doing some research work, and been stabbed in the back, the knife penetrating into her heart and the point of the knife coming out through her ribs at the front of her chest.’

‘That would have taken a lot of strength,’ said Daniel. ‘There were no witnesses?’

Steggles shook his head. ‘She was in an isolated corner of the reading room. She was found lying face down on the table, with blood by her.’18

‘You say she was doing some research,’ said Abigail. ‘Was she a student of some sort?’

‘No,’ said Steggles. ‘In fact, she seemed to have been someone from a poor background, to judge by her clothes. Her clothes were clean, but very worn and repaired many times. Indeed, her shoes had holes in the soles and newspapers had been put inside to give protection against cobbles.’

‘Do you know her name?’

Again, Steggles shook his head.

‘No. She gave no name, and there was no form of identification on her. She did have a bag with her, but that had gone. I assume whoever stabbed her took it.’

‘A robbery?’ hazarded Abigail.

‘Unlikely,’ said Daniel thoughtfully. ‘Whoever did it was obviously strong. If they simply wanted the bag all they had to do was take it from her. At worst, a punch to knock her out if she resisted. What do the police say?’

‘To be honest, that’s why we’ve asked you if you’d look into it. As far as the police are concerned, there is no case to investigate. A woman no one knows has died. There were no witnesses, so no sighting of a suspect. Her obvious poverty means to them she is of no importance. They say they haven’t the resources to waste investigating something that can’t be solved.’

‘That’s very harsh,’ said Daniel.

‘That’s what we thought. The board of the museum, that is. Although there’s been a museum in Manchester since 1821, this building was only opened seven years ago. It is our ambition to provide the resources for education not just for students and staff of the university, but for the wider public. Especially those from poor and deprived backgrounds. We are an establishment with a social conscience, as are many others in Manchester. We feel 19that the violent death of someone should not be ignored simply because they are poor or are not recognised as important to society. If the police won’t agree to look into this poor woman’s death, then we feel it is up to us to do something.’

A gentle knock at the door interrupted them.

‘Ah, that will be the tea,’ said Steggles.

He got up and walked briskly to the door, opening it to admit a kindly looking woman of middle age carrying a tray on which were cups and saucers and all the other accoutrements for tea, including a plate of mixed biscuits.

‘On the desk, please, Mrs Wedburn.’ Steggles smiled.

Once Mrs Wedburn had deposited the tray and departed, Steggles busied himself with pouring the tea to their specifications – milk for both, sugar for Daniel but not for Abigail – and served them, placing the biscuits within easy reach.

‘You said there was a second murder,’ said Abigail.

Steggles nodded. ‘That was only discovered this morning. There’d been reports of a foul smell inside the cellar. This morning Walter Arkwright, one of our attendants who also acts as our storeman, traced it to behind some packing cases. The body of a woman was there.’ He gave a shudder as he said, ‘Someone had sliced her face off.’

Abigail and Daniel stared at him, shocked.

‘How?’ asked Daniel. ‘What with?’

‘The police just said it must have been with a large, sharp blade. Someone had sliced off the front of her face, right back to the bones of her skull.’

‘Where is the body now?’

‘At the hospital mortuary, along with the body of the young woman.’

Daniel and Abigail were silent for a moment as they took 20all this in, then Daniel said, ‘Surely there are private enquiry agents here in Manchester, Mr Steggles. I say this because Miss Fenton and I are unfamiliar with the city. A local enquiry agent would have easier access to sources of information and local contacts.’

‘True,’ said Steggles. ‘But we have been following the successes the pair of you have had when murders have occurred at other museums. The Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, the British Museum, the Ashmolean in Oxford. On every occasion you succeeded when the local police force had failed.’

‘I wouldn’t say “failed”,’ said Daniel carefully. ‘On those occasions we worked with the local police force and were able to bring a different eye to the investigation. I have a policeman’s experience, but Miss Fenton is the one who is at home in a museum setting, and her instincts proved invaluable in those cases.’

‘Yes, we are very aware of Miss Fenton’s reputation,’ said Steggles. ‘I have read your articles concerning your excavations at Giza, and your recent work on Hadrian’s Wall. And we have some artefacts here from your own work at Hawara. We are privileged to have you here with us. I would deem it an honour for you to spend some time exploring the museum and letting us have your comments and recommendations.’

‘With the greatest respect, Mr Steggles, I feel that sometimes my reputation as an archaeologist has become somewhat inflated, possibly due to the rather purple prose of the popular newspapers.’

‘I am basing my opinion on reports on you and your work from other archaeologists and curators, Miss Fenton. Your peers hold you in high esteem.’

Abigail coloured, and Daniel had to hide a smile at the idea of Abigail blushing.21

‘Thank you, Mr Steggles. But, as far as conducting investigations, Mr Wilson gives me too much credit. The truth is, we complement one another and so bring different observations to cases.’

‘As we hope you will to this.’

‘But those other cases were connected to the museums,’ stressed Daniel. ‘We’re not sure if that’s the case here. We have to look at the possibility that these women may have been killed for reasons that have nothing to do with the museum.’

‘In which case, that will be a relief to us. The idea that in some way the museum may have been the cause of their deaths hangs heavy on us.’ He gestured at the plate. ‘Biscuit?’ he offered. He selected one himself and looked at it in a guilty fashion. ‘My wife says I eat too many of these and they’re bad for my health, but with the stress we’ve been under lately over this murder, it’s a relief to have some kind of solace.’

CHAPTER THREE

Replenished by tea and an occasional biscuit, Daniel suggested going to the reading room to examine the site of the murder, and then the cellar where the most recent body had been discovered.

‘Yes, I was just going to suggest that,’ said Steggles. ‘It will give you a chance to meet Jonty Hawkins. He’s the librarian in charge of the reading room, and it was he who discovered the first body.’

‘In that case we definitely need to make his acquaintance,’ said Daniel.

Steggles led the way to the reading room, this time their route taking them through the actual museum.

‘Hawkins is a remarkable young man. Many young men would have been too disturbed by the awful discovery he made to have been able to continue to work, but he absolutely refused my suggestion he go home. A fine young man. He’s also quite an accomplished 23poet. His work has appeared in magazines here in Manchester.’

They entered the reading room and Steggles led the way to the desk at which a young man was sitting, examining a book. He stood up as they approached, and Daniel and Abigail exchanged glances that meant they were both thinking the same: Jonty Hawkins was in his twenties, and his style of dress and manner was as far removed from the bank clerk appearance of Steggles as was possible. He was tall and thin and wore a long, green velvet jacket over a flowered waistcoat, but it was his long hair that caught their attention, curling luxuriantly over his ears and collar in the style of Oscar Wilde’s most ardent followers. There was even a hint of rouge on his otherwise pale face.

‘Mr Hawkins, these are Mr Daniel Wilson and Miss Abigail Fenton, the people from London I spoke about.’

Hawkins gave them a smile and held out his hand to shake theirs in greeting.

‘Welcome,’ he said. ‘I know of your reputations, of course. Yours in particular, Miss Fenton. Your work at Giza is an inspiration to all.’

‘You are interested in archaeology?’ asked Abigail.

‘Fervently,’ said Hawkins earnestly. ‘You must allow me to show you the pieces we have from Kahun and Hawara.’

‘Flinders Petrie,’ murmured Abigail.

‘You were with Petrie at Hawara, I believe,’ said Hawkins excitedly.

Abigail nodded. ‘I was.’

‘For the moment I’ve brought Mr Wilson and Miss Fenton here to talk to you about … what happened here last Thursday,’ interrupted Steggles, lowering his voice almost to a whisper.

‘Of course.’ Hawkins nodded. ‘My apologies.’

Steggles turned to Daniel and Abigail.24

‘I’ll leave you with Mr Hawkins. When you’ve finished with him perhaps you’d return to my office and I can give you directions to your hotel and details of the booking. Or, if I’m not available for any reason, my secretary, Mrs Wedburn, will be able to supply the information.’

Daniel and Abigail thanked him, and then turned back to Jonty Hawkins.

‘Perhaps it would be better if we moved outside,’ suggested Hawkins. ‘We can talk freely there.’ He gestured at the room, where already some of the people sitting at the various tables were glaring at them disapprovingly. ‘It is a reading room, after all, and people expect a quiet atmosphere.’

Daniel and Abigail nodded in acquiescence and followed the young man out of the reading room into the corridor outside.

‘We can talk here, but it’s still better if we keep our voices low.’

‘Of course,’ said Abigail. ‘Mr Steggles said it was you who found the body.’

‘Yes, and no,’ said Hawkins. ‘A man came to my desk and said there was a woman slumped over the table. To be honest, that’s not unusual. We get many people coming in here to seek shelter, and some of them fall asleep. It’s not something we encourage, but we don’t like to throw them out. Times are hard. But this man said he thought he saw blood on the table.’ He hesitated, then added, ‘It would make more sense if I show you where she was found, and you can see the arrangements for readers.’

‘Excellent idea,’ said Daniel. ‘But before we do that, as we can talk here, it would be useful to learn what you knew about her?’

‘Knew?’ said Hawkins. He gave a rueful sigh. ‘Very little, I’m afraid. She appeared on Wednesday last week and asked me if we had anything about the Manchester army from a long time ago. I told her that the army records are kept at the barracks. Much of 25what we have are newspaper reports about different campaigns. She said she’d been to the barracks but they hadn’t been able to help her. I said the barracks was still her best choice, but she said she couldn’t go back there. I got the impression they’d turned her away quite harshly.’

‘She asked about the Manchester army?’ said Daniel. ‘Not a particular regiment?’

‘No,’ said Hawkins. ‘She said she was looking for information about the army from about eighty years ago.’

‘Eighty years,’ said Daniel thoughtfully. ‘1815. That would be during the Battle of Waterloo.’

‘Yes, but there was no actual Manchester army at that time, just other regiments that later formed it. The Manchester Regiment was created in 1881 with the amalgamation of the 63rd West Suffolk, the 96th Regiment of Foot, the 6th Royal Lancashire Militia and some volunteer battalions.’

‘You are a keen student of military history?’ asked Daniel, impressed.

‘Not really,’ admitted Hawkins. ‘I only found this information when I made enquiries about the Manchester Regiment, after the young lady asked me. And I’ve been helping Mr Steggles with some background work on the exhibition about the Manchester regiments he’s planning.’

‘Were these other regiments at Waterloo?’ asked Daniel.

‘No, but the 15th Hussars based at Hulme were, although I don’t think they can be described as purely a Manchester regiment.’

‘Did she find what she wanted in the documents you provided?’

‘I assume not, because she came back the next day and asked if I had any different papers about the old regiments. I asked her what she was actually looking for, but she said she’d know it if she saw it.’ His face looked troubled as he added, ‘It was during 26that second visit, last Thursday, that she was killed.’ He gestured towards the reading room. ‘Perhaps now would be a good time to show you where she was.’

Daniel and Abigail followed Hawkins back into the reading room, past long rows of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, before coming to four long tables. Each table was divided by wooden partitions into six small compartments.

‘The official reason for putting the partitions on the tables in this way was so that each person has privacy for their research,’ explained Hawkins as they approached the tables.

‘And the unofficial reason?’ asked Abigail.

Hawkins gave a rueful smile.

‘Before we put the partitions in place, some people would spread their books and papers so far out they’d take up the whole table, which led unfortunately to strong arguments. This way, readers can only have what they can fit into their compartment.’

There were a handful of people at the tables, some with newspapers, some with books, some scribbling notes, others just reading. Hawkins led the way to the furthest of the tables. Two men were sitting in the compartments, both intent on their work. One, a bearded man, looked up as Hawkins, Daniel and Abigail arrived, then he turned back to the pile of books he’d assembled.

Hawkins stopped by an empty compartment at the end of the table.

‘She was here,’ he said. ‘There was no one else at any of the tables. She was slumped across the table. I tapped her on the shoulder, then – when she didn’t respond – very gently raised her to sit up so I could see how she was, and then I saw the blood staining the front of her blouse and that it had run down.’

‘That must have been a dreadful experience for you,’ said Daniel sympathetically.27

‘Awful,’ said the young man. ‘I’ve seen dead people before – you’d be surprised how many come in here for warmth and then die – but not like this. The police said she’d been stabbed in the back and the knife had gone deep into her heart and out through her ribs at the front.’ He shook his head. ‘It makes me sick just to think of it.’

‘What else did the police say?’ asked Daniel.

‘Not much,’ said Hawkins. ‘In fact, they didn’t seem unduly concerned. The inspector in charge said he didn’t think it worth investigating as no one knew who she was. I think that was because she was dressed in shabby clothes and obviously poor. And when I told him she was Irish …’

‘Irish?’

Hawkins nodded. ‘There are a lot of Irish in Manchester. The inspector said he expected it was some boyfriend she’d upset. When I told him that the bag she’d brought with her had gone, he said that was the answer: it was a robbery.’

‘Yes, Mr Steggles told us the police said they wouldn’t be investigating. Did you get this inspector’s name?’

‘Inspector Grimley.’

‘Where can we find him?’

‘He’s based at Newton Street police station. It’s not far from London Road railway station.’ He hesitated, then added warily, ‘He didn’t seem the most compassionate of people. But perhaps he’ll be different with you, Mr Wilson, you being an ex-Scotland Yard detective.’

‘What about where the most recent body was found? The one this morning.’

‘The cellar,’ said Hawkins. ‘I wasn’t involved in that. I only heard about it afterwards.’

‘We understand the body was found by Mr Walter Arkwright. Is he still here?’28

‘He is. If you come this way, I’ll take you to him.’

They followed Hawkins downstairs to the reception area, where an elderly man in the blue uniform of a museum attendant stood to attention, back ramrod straight, hands behind his back, as he surveyed the people coming and going.

‘Mr Arkwright,’ said Hawkins. ‘These are Mr Daniel Wilson and Miss Abigail Fenton.’

Arkwright nodded. ‘Yes. Welcome. Mr Steggles told me you’d be coming.’

‘We understand you found the body in the cellar this morning.’

‘I did, sir,’ said Arkwright crisply. ‘I assume you wish to see where I found it?’

‘Yes, please.’

‘I’ll leave you in Mr Arkwright’s care,’ said Hawkins. ‘If you wish to talk to me again, you’ll find me in the reading room.’

Daniel and Abigail followed the elderly attendant through a door, then down some stone steps, a musty smell coming to them as they descended deeper.

‘Damp,’ observed Arkwright. ‘You’ll always get that in cellars. Luckily this place has been well-built so at least you don’t have rats getting in.’

At the bottom they came to a large room with a floor of flagstones, other rooms going off it. Each room was stacked with wooden packing cases, some large, some small.

‘Pieces awaiting exhibition,’ Arkwright informed them. ‘Every so often the displays are changed to keep people coming. Not every one, though. Some are always kept as they are because they’re so popular that people keep coming back to see them. Like the remains of the dodo, for example. Now that’s a rarity.’

He took them to where a stack of smaller wooden crates was piled one of top of the other in one of the inner rooms.29

‘This is where I found her,’ he said. ‘I came down as I always do when I come in, and I knew that smell straight away. The smell of death. An old soldier, see. At first I thought it might have been something like a cat had got in and died, but the nearer I got to these crates, the stronger the smell of blood. I pulled the crates out, and there she was. She’d just been stuffed behind them and the crates pushed back.’ He shook his head. ‘It were a mess. Someone had bashed her head in, then sliced her face clean off, right back to the bone. All the skin and flesh gone.’

‘It must have been a dreadful experience for you,’ said Abigail sympathetically.

‘Like I said, I’m an old soldier, miss. I’ve seen a lot worse than that.’

‘Was there any sign of the remains of her face?’ asked Daniel.

Arkwright shook his head. ‘He must’ve took it with him. Mebbe a trophy. I’ve known that happen in wars. Soldiers collecting the ears of their enemies. But never a whole face.’

Daniel knelt down and studied the area behind the wooden crates where the body had been lodged.

‘The signs are that you’ve cleaned up the blood here,’ he said.

‘I have, sir. Couldn’t have that sort of thing making a mess here.’

Daniel pointed to the floor a few feet away from the packing cases.

‘This must be where he took her face off,’ he said.

‘Correct,’ said Arkwright. ‘That’s where most of the blood was. It took a lot of scrubbing.’

‘And you’ve done a very good job, Mr Arkwright,’ complimented Daniel.

As Daniel and Abigail headed back up the stairs towards Steggles’s office, Abigail said, ‘I presume that Mr Arkwright’s zealous cleaning has removed any possible clues that might have been there.’30

‘Indeed,’ said Daniel. ‘But one can’t blame him. He was doing his job. And I assume he was told he could clean up by this police inspector, who must have come to look at the dead body and the scene of the crime.’

As they approached Steggles’s office, Abigail asked, ‘What did you make of Mr Hawkins?’

‘I liked him,’ replied Daniel. ‘Despite the fact that he decides to dress in the style that emulates Oscar Wilde and the aesthetic movement. That alone I think would take some courage in an industrial town like Manchester, but he gave a very lucid and thoughtful report of his encounters with the young woman. Intelligent.’

‘I’d be interested in looking at some of his poetry. That often gives the measure of someone. Whether they are genuinely gifted, or whether it’s all just superficial appearance.’

‘I’m sure he would be only too pleased to share his works with you,’ Daniel said. ‘I got the impression he was quite admiring of you.’

‘Of my work and reputation, in reality, I expect,’ said Abigail. ‘I somehow feel I may not be the right object of affection for young Mr Hawkins.’

‘You are for me.’ Daniel smiled.

‘And that’s all that matters to me.’ Abigail smiled back.

Steggles was still in his office, looking forward to hearing their initial report. They both made a point of complimenting Jonty Hawkins and Walter Arkwright to him.

‘Two very good witnesses,’ said Daniel.

‘Yes,’ said Steggles, but they could both tell he seemed uncomfortable at the mention of their names.

‘Is there an issue with either of the men?’ enquired Abigail.

Steggles gestured for them to sit, then said, ‘It’s not either of 31them personally, rather something that Mr Hawkins said about the young woman found in the reading room. He said that she was looking into old records of the Manchester units of the army, and she was doing that because she was turned away from the barracks when she made her initial enquiries there.’

Abigail nodded. ‘Yes, he told us the same.’

‘I’m concerned because I’ve been having discussions with Brigadier Wentworth, the Commanding Officer at Hulme Barracks, and a local military historian, Hector Bleasdale, about mounting an exhibition here highlighting the achievements of the Manchester regiments.’

‘Yes, Mr Hawkins mentioned it,’ said Daniel.

‘We are very keen to involve as many sections of the local community as we can, to bring the public into the museum so they can see it as their museum. For their part, I believe the army is keen because it would counter some of the stories about Peterloo.’

‘Peterloo?’ asked Abigail.

Steggles looked at her in surprise. ‘I thought what happened at Peterloo was common knowledge,’ he said.

‘Not to me,’ said Abigail.

‘Nor me,’ added Daniel. ‘What was it?’

‘It was an unfortunate incident that happened here in Manchester in 1819. There was a … a riot at a public meeting. The army was called in and a number of civilians died.’

‘Killed by the army?’

Steggles nodded. ‘I’m sure there are any number of people in Manchester who will be able to furnish you with the details far better than I can. Although it is still a sensitive subject as far as the army are concerned.’

‘Understandably,’ said Abigail.

‘That’s one of the reasons we’ve been discussing the idea of an 32exhibition about the local regiments, to promote the positive side of the army and help to heal any divisions between them and the civilian populace that may still exist.’

‘Divisions after eighty years?’ asked Abigail.

‘People have long memories, and sometimes the stories that get handed down from generation to generation can be distorted,’ said Steggles. He gave an unhappy sigh. ‘My concern is that if the army are implicated in any way in this young woman’s death, however obliquely, they may decide not to collaborate with us. Which would be a pity; the army is a core part of Manchester society with a long and prestigious military tradition.’ He hesitated, then added awkwardly, ‘Apart from what happened at Peterloo, of course. But even then, it could be argued that wasn’t the regular army at fault, but a local militia.’

‘We will need to go to the barracks to ask questions,’ said Daniel. ‘About the young woman going there and being turned away.’

Steggles nodded. ‘I understand. It’s at Hulme. You’ll be able to get a hansom cab, or buses go there. But I would ask you to be discreet.’

‘We will be, I can assure you,’ said Daniel. ‘Perhaps if we spoke to this commanding officer you mentioned …’

‘Brigadier Wentworth,’ said Steggles. ‘Yes. And by all means mention my name. He’s a good chap.’ He hesitated, then added, ‘Although, a bit of a stickler for rules and regulations. Comes with being part of the army, I suppose. I hope this business of the young woman doesn’t put a block on the exhibition we’re planning. We like to be very active.’

‘Yes, I saw a poster for an illustrated talk on tropical birds you have coming up,’ said Abigail.

At this, Steggles brightened. ‘Indeed! Given by none other than Henry Eeles Dresser, acknowledged across the world as the expert on exotic birds. As well as being a former secretary of the 33British Ornithologists Union he’s also an Honorary Fellow of the American Ornithologists Union. And his studies in Eastern Europe, especially in Finland …’ He stopped and gave an apologetic smile. ‘Forgive me. Sometimes I get overenthusiastic and go on alarmingly. My wife is always telling me off about it.’

‘Not at all,’ said Abigail. ‘I’m a great admirer of enthusiasm, especially when it’s accompanied by expertise. If we’re still here when Mr Dresser gives his talk, Mr Wilson and I will be delighted to attend.’

And Abigail shot a look at Daniel, who said as politely as he could, ‘Indeed. It would be a pleasure.’

‘In the meantime, I would urge you to take a look at our ornithology section here at the museum,’ said Steggles. ‘We have an array of wonders among the exhibits, including the bones of a dodo, a male and female ivory-billed woodpecker, stuffed birds, eggs and bones from the Hawaiian islands, and many examples of rare exotic species. Not to mention some wonderful examples donated by Charles Darwin following his important journeys, including a very rare warbler finch.’

‘We certainly will.’ Daniel got up. ‘But right now, we need to book in at our hotel, and then make ourselves known to the local police inspector in charge of the case.’

‘Inspector Grimley at Newton Street police station,’ answered Steggles. He rose, saying carefully, ‘A … difficult man, from what little I saw of him. Rather abrasive. But I’m sure he is good at his job.’

Steggles handed them the address of the Mayflower Hotel.

‘Your room reservations are in the name of the museum,’ he said. Then he hesitated, before adding in an awkward tone, ‘Initially I reserved two rooms, one for each of you, but I have since learnt that you are – ah – quite close. I therefore took the 34liberty of adding a rider to the reservation that you may decide to – ah – share a room.’ As Abigail and Daniel stared at him, he added, ‘Because the Mayflower is quite a conventionally managed hotel, I told them that it was my understanding that you were married but that you, Miss Fenton, elected to be known by your maiden name because of your international renowned reputation as an archaeologist. I hope you will not be offended by my temerity.’

As he said this, Steggles’s face, and especially his ears, became suffused with colour, and they realised that he was blushing. It was Abigail who moved forward and took his hands in hers.

‘Mr Steggles,’ she said, her voice trembling with passion, ‘that is one of the nicest things anyone has ever said to me, and we are both eternally grateful to you. I will not lie to you, we are married in all but name, and have every intention of marrying as soon the opportunity arises. But your generosity here …’ Temporarily words failed her, and instead she squeezed his hands. ‘You don’t know what a weight off my mind your kind words have been.’

CHAPTER FOUR

‘A talk about birds,’ groaned Daniel as they left the museum.

‘It will be instructional,’ defended Abigail. ‘And it will keep our client happy.’

‘I can imagine nothing more boring,’ said Daniel. ‘The only birds I’m familiar with are the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, who seem to make me a target as soon as I venture there. The number of times I’ve had to get pigeon excrement removed from my hat …’

‘Exotic birds are not the same as pigeons,’ countered Abigail.

‘I bet they’d still drop their deposits on me if I was in some tropical jungle. I expect Charles Darwin returned from his travels with his coat spotted with their droppings.’

‘Unlikely,’ said Abigail. ‘I’m sure Mr Dresser’s talk will enlighten you.’36

Despite the authorisation that Steggles had given the Mayflower Hotel, as they were taking just the one room, the receptionist insisted they sign the register as Mr and Mrs Wilson.

‘It’s a small price to pay,’ said Daniel as they made their way to their room.

‘I have never given up my name before,’ said Abigail.

‘Perhaps we should have signed as Mr and Mrs Fenton?’ suggested Daniel.

‘Would that worry you?’ asked Abigail.

‘No,’ said Daniel. ‘However, as the hotel had already been told who I was before our arrival, I don’t think we could have got away with it.’

‘How thoughtful of Mr Steggles!’ exclaimed Abigail as they unlocked the door of their room and entered. ‘No rumpling the bed linen in one of two rooms to keep up a ludicrous pretence. I hope there’s a Mr Steggles in every case we are hired to investigate. It’s a relief to meet such enlightenment.’

‘It’s also time for us to meet Inspector Grimley,’ said Daniel. ‘However, based on what we heard from both Mr Steggles and Jonty Hawkins, I’m not expecting very much in the way of a welcome.’

Daniel’s expectations were confirmed as soon as they were shown into the inspector’s office at Newton Street police station. Inspector Grimley was sitting behind his desk as they entered, a uniformed sergeant standing beside him, and there was no mistaking the look of venom on the inspector’s face as he looked at them. He did not get up from his chair to greet them, nor offer to shake hands.

‘You wanted to see me?’ he grunted.

‘Yes, and thank you for making the time to see us, Inspector,’ 37said Daniel. ‘I’m Daniel Wilson and this is Miss Abigail Fenton. We’ve been asked by the Manchester Museum to look into the killing of the two women there, and we thought it only courtesy to let you know of our involvement, and that possibly we may be able to exchange information as and when we come up with any.’

Grimley glowered sullenly at them, then grunted, ‘There is no case.’

‘Yes, that’s what the museum said you’d told them, but as a young woman has been stabbed to death and the other we’ve been told had her face sliced off …’

‘People die violently all the time,’ snapped Grimley. ‘Sometimes through accident, sometimes they’ve been assaulted. We’re dealing with hundreds of cases here in this city, which means we have to prioritise, so the first thing we have to find out is who the person is who’s died, or if there were any witnesses. In this case both persons are unknown, and there were no witnesses. So there’s no chance of us finding out who killed either woman. If we had the luxury of a large force with lots of men, and spare time, like they seem to have in places like London, it might be different. But that’s the way it is.’

‘So you’re not going to investigate?’

‘We investigated and decided there was no point in spending more time on it.’

‘But two women are dead!’ exclaimed Abigail.

‘In the case of the young woman, I expect it was an angry boyfriend who did it, or possibly a petty thief as her bag was taken. The woman in the cellar … who knows. But we haven’t got the men or the time to go chasing that sort of thing when we’ve got cases we can go after. Now, if you’ve finished, I’ve got work to do.’38

‘Inspector, we are not just amateurs poking our noses in,’ said Abigail angrily. ‘Before he became a private enquiry agent, Daniel Wilson was a vital member of Inspector Abberline’s team at Scotland Yard …’

‘I knew who he was as soon as he introduced himself,’ snapped Grimley, ‘and we don’t need people from London coming up here to try and teach us how to do our job. Especially people who’ve failed at it themselves.’

‘Failed?!’ echoed Abigail.

‘You never caught the Ripper, did you?’ Grimley scowled at Daniel. ‘For all your fancy London ways. We may be far away, but we know what goes on. You failed at the Met, so now you’re making money out of misguided fools like the museum here. Well, you’ll get no encouragement on that score from us. Just be thankful I’m not arresting you for taking money under false pretences.’

‘At least they didn’t throw us out,’ said Daniel as they left the police station.

‘He did throw us out!’ burst out Abigail.

‘Yes, but not physically.’

‘I’d have liked to have seen him try!’ growled Abigail.

‘At least we know where we stand in relation to the local police,’ said Daniel ruefully. ‘So far we’re not having a great deal of success.’

‘We have only just arrived,’ Abigail pointed out.

‘True,’ conceded Daniel. ‘But you must agree we haven’t got a lot to go on, and with the police being obstructive … If only we knew what she was looking for at the museum. Hawkins said she wanted to research army records from eighty years ago, but that covers an awfully large area of information. Was she 39looking for a particular soldier? Or a particular unit?’

‘Hawkins said she’d been to the barracks first, and been turned away,’ said Abigail.

‘Yes, so that should be our next port of call. But with discretion.’