7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Museum Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

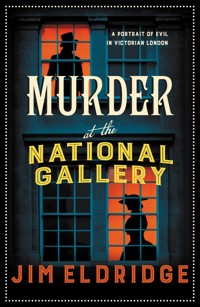

A grim portrait of murder in Victorian London. 1897, London. The capital is shocked to learn that the body of a woman has been found at the National Gallery, eviscerated in a manner that recalls all too strongly the exploits of the infamous Jack the Ripper. Daniel Wilson and Abigail Fenton are contacted by a curator of the National Gallery for their assistance. The dead woman, an artist's model and lady of the night, had links to artist Walter Sickert who was a suspect during the Ripper's spree of killings. Scotland Yard have arrested Sickert on suspicion of this fresh murder but it is not the last. Copycat murders of the Ripper's crimes implicate the artist who loves to shock but Sickert insists that he is innocent. Who would want to frame him? Wilson and Fenton have their work cut out catching an elusive and determined killer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

MURDER AT THE NATIONAL GALLERY

JIM ELDRIDGE

For Lynne, for always

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

London, February 1897

Daniel Wilson, formerly a detective sergeant with Scotland Yard and now a private enquiry agent, sat in his favourite wooden armchair in the kitchen of the small terraced house in Camden Town he shared with his partner in life and business, Abigail Fenton, the noted archaeologist and Egyptologist. They made an interesting couple, an apparent attraction of opposites: both were in their mid-thirties, Abigail, a Classics graduate of Girton College in Cambridge, tall, her red hair emphasising her high cheekbones adding to her elegance; and Daniel, the workhouse orphan, tall and muscular, his broken nose giving him the appearance of a bare-knuckle fighter. But sympatico is in the soul, not externals, and both Daniel and Abigail had found a deep empathy with one another when they’d first met three years previously, when Daniel was in Cambridge, hired to investigate a mysterious murder at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

They’d moved into Daniel’s small house in what was generally considered the slum area of Camden Town because it was where Daniel had grown up, but since then they’d talked about moving to a better area, and – more importantly – getting married and formalising their relationship. In the poorer areas, like Camden Town, marriage was often considered an expense that couldn’t be afforded; so couples moved in together and the woman adopted the man’s surname; and, to all intents and purposes, they were a married couple. As the poor had no property there would be no arguments over sharing the proceeds of the marital house in the event of a split. If questions were ever raised by officials about their marital status, the usual reply was that the wedding certificate had somehow got lost. The fact was that their neighbours recognised them as married, their children and the children’s mother bore their father’s name, so they were married.

The same standards did not apply to those of the middle and upper classes. To Abigail’s sister, Bella, who still lived in Cambridge, Abigail and Daniel were living in sin, and a disgrace to the family. Bella herself was married to a doctor, a very respectable situation.

Daniel and Abigail wanted to marry, not for society’s sake but as a pledge of their love for one another, a relationship they both intended to be in for life. They’d come close to it a couple of times but always something seemed to interfere, usually a murder case at one of the nation’s great museums that needed investigation. After their first case together at the Fitzwilliam, their reputation had grown and they’d been hired to investigate murders at the British Museum, the Ashmolean in Oxford, the Manchester Museum, the Natural History Museum and Madame Tussauds.

Now they were in a fallow period as far as detection was concerned, and Abigail could return to her first love: archaeological exploration. She’d agreed to lead an expedition, funded by Arthur Conan Doyle, to the sun temple of Niuserre at Abu Ghurob, part of the area in Egypt known as the Pyramids of Abusir. The plan was for the expedition to begin in June or July. At the moment, Doyle was making financial arrangements, while Abigail studied what was known about the pyramid they would be exploring. Both Daniel and Abigail had agreed that any thought of their wedding, or moving house, should be on hold until the expedition had been completed and Abigail returned to England.

Both of them viewed the expedition with mixed feelings: it would be the climax to an already brilliant career for Abigail; only one woman before, Lady Hester Stanhope, had led such an expedition and lent her name to it. But both of them were aware that Abigail would be in Egypt for a long time, and they would be separated. Daniel had determined to go and visit the dig while it was going on, but it wouldn’t make up for the fact that for the past three years they’d spent barely a day apart.

Daniel looked fondly at Abigail as she sat at the kitchen table, studying maps and texts she’d been allowed to borrow from the British Museum, then returned to reading the morning’s newspaper. He read the reports of the latest political arguments that were raging around the prime minister, Lord Salisbury, as once more efforts were made by the Home Rule faction to press the government to give independence to Ireland. It was an argument that had been going on for as long as Daniel could remember, with strong emotions on both sides of the debate. He turned the page and as his eye fell on a story on the second page, his mouth dropped open.

‘My God!’ he said, shocked.

‘What?’ asked Abigail.

‘Walter Sickert’s been arrested.’

‘The artist?’

‘Yes. They say he’s being questioned over the murder of a prostitute whose body was found at the entrance to the National Gallery first thing yesterday morning. According to this, she’d been eviscerated.’

Abigail stared at him, bewildered.

‘Walter Sickert?’ she repeated.

‘It’s like déjà vu,’ said Daniel. ‘We had him in for questioning during the Ripper investigation, Fred Abberline and myself.’

Abigail came and took the newspaper from him and scanned the page.

‘This is unbelievable,’ she said.

‘That there’s been another murder in the same manner as the original Jack the Ripper killings, or that Sickert’s been arrested on suspicion?’ he asked.

‘Both,’ she replied. ‘I see that Chief Superintendent Armstrong is in charge of the case.’

‘Chief Superintendent? Another promotion? That man knows how to climb a greasy pole,’ commented Daniel.

There was a knock at their front door, and Abigail handed the newspaper back to Daniel and hurried to open it. When she returned she was holding a small brown envelope.

‘It’s addressed to you,’ she said.

Daniel opened the envelope and took out the single sheet of paper.

‘Well, well,’ he said. ‘This is very timely. It’s from Stanford Beckett, the curator at the National Gallery. He wants our help.’

‘No, he wants your help,’ Abigail corrected him. ‘It’s addressed to you.’

‘But Beckett’s note asks for both of us,’ said Daniel. He held out Beckett’s letter to her.

‘In that case why wasn’t my name on the envelope?’ she asked, obviously annoyed.

‘I suspect it’s to do with the fact that I’ve met Sickert before, during the Ripper investigations.’ He stood up. ‘Shall we go?’

CHAPTER TWO

Stanford Beckett, curator of the National Gallery, was the epitome of the Victorian gentleman: a man in his sixties with a high, starched white collar to his shirt, a neat but colourful tie, bushy side whiskers, and an elegant pinstripe suit in charcoal grey, the image slightly marred by the amount of cigar ash on the front of his jacket. He put his half-smoked cigar into the ashtray on his desk, where it smouldered, as he gave a heavy sigh and looked at Daniel and Abigail with mournful eyes.

‘Tragic,’ he said. ‘Absolutely tragic.’

‘Could you tell us what happened?’ asked Daniel. ‘All we know is what we read in the newspaper, that a prostitute was found murdered and mutilated at the entrance to the National Gallery yesterday morning, and that Walter Sickert has been taken in for questioning on suspicion of her murder and is currently being held at Scotland Yard.’

‘Yes,’ nodded Beckett, with a heavy sigh. ‘Dreadful. Although it’s unfair to label her simply as a prostitute. I believe she also engaged in … er … that profession, but primarily she was an artist’s model.’

‘Who modelled for Sickert, I assume,’ said Daniel.

‘Yes.’

‘And do we know why Sickert was arrested? And so quickly?’

‘No,’ admitted Beckett helplessly. ‘The police say it was the result of information received.’

‘And he’s been held in custody since yesterday afternoon?’

‘Yes,’ said Beckett. ‘His wife, Ellen, informed me that the police came to the house with a warrant for his arrest and took him in, charged on suspicion of murder. Today I received a message from him asking me to get in touch with you. He seems to feel that you might be able to get him out of custody.’

Daniel frowned. ‘A message? I find it hard to believe that Chief Superintendent Armstrong allowed him to write to you? The chief superintendent is notorious for applying the rules rigidly to people he takes into custody to ensure they have little outside contact while he’s questioning them. Lawyers are allowed, of course, but even then, the chief superintendent has been known to make things difficult for them.’

‘This message came through Ellen. She was allowed to visit her husband early this morning, although – as you suggest – not without difficulty.’

Daniel smiled. ‘I can imagine. But, having met Mrs Sickert, she can be quite formidable.’

‘Yes, although it was fortunate that when she called at Scotland Yard this morning, Chief Superintendent Armstrong had not yet arrived, so she was dealing with the turnkey, which is I believe the correct term. She managed to get a meeting with Walter, who asked her to ask me to contact you.’

‘I can’t see how I can be of much help in this case. I’m no longer with the police force and I have no authority with them.’

‘Nevertheless, he asked if you’d at least see him.’

‘I’m not even sure if we’d be allowed to,’ said Daniel doubtfully.

‘You might, if you’re going on behalf of the National Gallery,’ said Beckett. ‘We are a highly reputable and well-respected organisation, and we believe Walter is one of Britain’s truly great artists.’

‘I’m not sure if that will have any sway over Chief Superintendent Armstrong,’ said Daniel. ‘He’s not known for his appreciation of art and artists.’

‘Won’t you at least try?’ asked Beckett appealingly. He gave a slight shudder as he added: ‘When Ellen came to see me this morning, she was very angry and insisted that I do something.’

‘Yes, I have seen Mrs Sickert when she’s angry,’ said Daniel, doing his best not to smile. ‘Very well, we’ll try, but we’ll need something to say that we’re acting on behalf of the National Gallery.’

‘That will be no problem,’ said Beckett, relieved. ‘I’ll give you a note over my signature saying you’ve been authorised to act on our behalf.’ He took a sheet of letterheaded notepaper from a small pile on his desk, dipped his pen into his inkwell, and began to write a brief letter. When finished, he pressed it on his blotting pad and passed it to Daniel.

‘I suggest we leave it until we’re sure the ink is dry,’ said Daniel. ‘We don’t want to take a smudged letter in with us, it’ll lessen the impact. While we’re waiting for it to dry, perhaps you can show us where the unfortunate woman was found.’

‘Of course,’ said Beckett getting to his feet and leading the way.

‘Do you know her name?’ asked Abigail. ‘There was no mention of it in the newspaper report.’

‘Her name was Anne-Marie Dresser.’

‘And she modelled for Walter Sickert.’

‘Among others. Her face is quite recognisable when you look at some of the portraits by different hands.’

‘Have you some on display?’

‘We have one by Walter and one by Edgar Degas.’

‘Degas painted her?’ asked Abigail. ‘Here, in England?’

‘Yes. Degas was a frequent visitor to these shores before his eyesight began to fail. He’s also great friends with Walter. Walter says that it was Degas who taught him how to represent reality on canvas. They shared many interests.’

‘Including the same model,’ commented Abigail drily.

‘Er … yes. I believe that may have been the case,’ said Beckett, forcing an awkward smile.

They passed through the main doors and into the portico-covered entrance of the National Gallery, overlooking Trafalgar Square with its four stone lions protecting the imposing edifice of Nelson’s Column.

‘She was found here,’ said Beckett, pointing to the low wall at the side of the entrance area.

Daniel crouched down and examined the flagstone area.

‘The newspaper said she had been eviscerated. Ripped open and her internal organs taken. I assume your staff have done a good job of cleaning up all traces of the blood.’

‘That was one of the unusual aspects,’ said Beckett. ‘There was, in fact, very little blood.’

‘Suggesting that the crime was committed somewhere else and her body was dumped here,’ said Daniel.

‘Yes,’ nodded Beckett.

‘Who found the body?’

‘The cleaners, when they arrived for work. They saw her lying there and thought she must be some tramp, or someone drunk. Her face and body were turned into the wall. It was only when they shook her by the shoulder to wake her up that the body rolled and the horror of what had been done to her was revealed.’

‘Have the police spoken to the cleaners?’ asked Abigail.

‘I believe so,’ said Beckett. ‘Will you wish to speak to them?’

‘At the moment this is a police investigation and our role, as I understand it, is just to try and get Walter Sickert out of custody. Unless you’re asking us to investigate the murder?’

‘Not at the moment,’ said Beckett. ‘That would be a decision for the Board of Trustees, and only if it was felt appropriate. At the moment we’re putting our faith in the police to carry out their investigation. What we’d like, as Walter has requested, is for you to try and obtain his release. That is our priority. If you’re unable to, then we shall inform Ellen and leave it to her to decide the next course of action. Whatever happens, you will of course be paid.’

‘Thank you,’ said Daniel. ‘We’ll collect the letter from your office and head for Scotland Yard.’

‘Before we do, can we see the two portraits of Anne-Marie you mentioned, by Sickert and Degas?’ asked Abigail.

‘Of course, Follow me.’

As they walked back into the building and followed the curator through the galleries, Beckett said: ‘Of course, much of this will be changing when the National Gallery of British Art opens at Millbank later this year.’

‘The Tate Gallery,’ said Abigail.

‘Yes, I believe that is what people are calling it, and perhaps that will eventually be its official title.’ He saw the puzzled expression on Daniel’s face and explained: ‘It was founded and paid for by Sir Henry Tate, the sugar magnate. It will house works by British artists born after 1790, so Sickert’s paintings will be transferred to there.’ He stopped in front of a large picture of a nude woman standing in a bowl of water in a bedroom and wiping her naked body with a flannel. ‘Here we are, Walter’s portrait of Anne-Marie.’

‘It’s full of life,’ commented Abigail. ‘And he’s captured the apparent poverty of her surroundings.’

‘I think he may have exaggerated the poor conditions,’ admitted Beckett. ‘As far as I know, she lived in a room that was furnished quite reasonably. I suspect he may have chosen a less salubrious location for this picture. Walter does like to play what he calls “the proletariat card” in his work. Ordinary working people at leisure, and not engaging in what could be called “genteel pastimes”.’

‘In other words, he likes to shock,’ commented Abigail.

‘I think there may be an element of that,’ Beckett agreed.

He then led them through to a gallery where French painters were on display. The woman in the picture he stopped in front of was recognisable as the same woman in Sickert’s picture. Both artists had captured the hungry, almost vulpine look in the woman’s eyes, made more so by her pale face, high cheekbones, and long, lank, greasy dark hair hanging down. In Degas’ picture of her she was standing in front of a full-length mirror admiring herself. The artist had captured both her back view and the reflection of her naked front in the mirror. As with the Sickert painting, Degas had caught the life force of her. Here she was living, animalistic, vibrant. And now she was dead, butchered.

‘She’s very confident in her nakedness,’ observed Abigail.

‘She was a very confident young woman,’ said Beckett.

As they left the gallery, Abigail asked Daniel: ‘What did you think of the paintings?’

‘They’re different to what I’ve been used to,’ he admitted. ‘They’re almost semi-finished sketches. But I liked them. I thought they brought her to life more than some of these paintings that are painted to perfection.’

‘It’s called post-Impressionist,’ said Abigail.

‘Post-Impressionism?’

‘It follows on from the original Impressionists: Manet, Monet, Renoir, all French. Our own Turner was said to be an inspiration for them.’

‘Turner?’

‘Joseph Mallord William Turner. The Fighting Temeraire. Very impressionist.’

‘This is all foreign to me,’ admitted Daniel. ‘I can see that if this becomes a case for us, you’re going to have to be my guide.’ He turned to her and said: ‘You already knew all that about the new Gallery of British Art, didn’t you?’

‘Yes,’ said Abigail. ‘It was in one of my magazines. But I didn’t like to spoil Mr Beckett’s telling us about it.’

CHAPTER THREE

Chief Superintendent Armstrong wasn’t at Scotland Yard when they arrived, to Daniel’s relief as he’d always had a difficult relationship with him. It had been hard enough when Daniel had been a detective sergeant, but it had got worse since Daniel retired from the force, especially because of his successes as a private enquiry agent, something that Armstrong seemed to take as a slur on the police, and himself in particular. This situation wasn’t helped by those journalists with little liking for Armstrong who’d invented the title of ‘The Museum Detectives’ for Daniel and Abigail, highlighting their successes in those cases and making a point of contrasting them with Scotland Yard’s failures.

Their old friend, Inspector John Feather, was in, and it was to him that Daniel showed the letter from Stanford Beckett. Feather grinned as he handed it back to Daniel.

‘Good, this’ll cover my back if the chief superintendent finds out you’ve been here.’

‘Don’t tell me we’ve been barred from Scotland Yard again,’ said Abigail indignantly as they followed Feather up the wide ornamental staircase to his office on the first floor.

‘Not officially. It’s just in this case, with your past experience in the original Ripper killings, Daniel, he’d prefer it if you weren’t involved.’ He gestured at the letter from Stanford Beckett as Daniel put it back in his pocket. ‘He’ll be upset when he hears about this.’

‘What do you know, John?’

‘Anne-Marie Dresser, part-time artists’ model, part-time prostitute. Her body was found yesterday morning outside the entrance to the National Gallery. Her abdomen had been ripped open and her internal organs removed.’

‘And you arrested Sickert. Why?’

‘Two things,’ said Feather as he walked into his office and gestured for them to sit. ‘One, the murder was a copy-cat of the Jack the Ripper killings from nine years ago. And you especially, Daniel, will remember that Sickert was a strong suspect at the time, you and Abberline being in the thick of it. I was only a detective constable then, but even I did my bit, as did every copper on the force, because it was such a big case.’

‘It’s still not enough to arrest Sickert,’ said Daniel.

‘No, but this was the clincher,’ said Feather. He reached into his desk and took out a sheet of paper, which he passed to them. ‘It was left at the front desk late yesterday afternoon.’

On the paper were the words ‘The tart wot was killed at the National Gallery. It was the painter Sickert wot dun it.’

‘Interesting,’ mused Daniel. ‘They can’t spell “what” and “done”, but they can spell “National Gallery”.’

‘Yes,’ nodded Feather, taking the letter back and putting it back in his desk. ‘Someone educated pretending to be semi-literate? Anyway, we went in search of Sickert and found him at home, packing to leave for Venice. Doing a runner, in the chief super’s opinion.’

‘So you brought him in.’

‘We did. He claims he hadn’t seen Anne-Marie for three days.’

‘But he admits knowing her. She was his model.’

‘A bit more than that,’ chuckled Feather. ‘In fact, he told us he brought her back with him after one of his trips to France. From Dieppe, which is where he met her. He set her up in a room in Cumberland Market.’

‘Did his wife know about this arrangement?’ asked Abigail.

‘I don’t know,’ said Feather. ‘We didn’t get a chance to ask her. She was pretty angry when she found out why we were there and spent most of the time hurling abuse at us. It didn’t seem the right time to ask her.’

‘She’s quite a character,’ smiled Daniel. ‘I remember meeting her during the Ripper enquiry. She and Sickert had quite a tempestuous relationship.’

‘They still do, by all accounts,’ said Feather. ‘At least, that’s the impression we get from the servants. So, what’s your angle in all this? Don’t tell me the National Gallery have brought you in to solve the murder. I’d have thought it’s a bit soon for that.’

‘No,’ said Daniel. ‘They want us to try and get Sickert released.’

‘Not a chance,’ said Feather. ‘The chief super’s firm on this. He’s sure that Sickert did it. He wants to nail him. He’s aiming to get a confession from him before the lawyers get on to the case.’

‘How’s he keeping them at bay?’ asked Abigail. ‘It’s a legal requirement that a person accused has access to a solicitor.’

‘Armstrong’s an old hand at this game,’ said Feather. ‘He keeps pulling obscure bits of legislation out of the hat. It won’t last – give it a day or so and Sickert will get to meet his legal people. But the chief super’s hoping by then he’ll have enough to proceed.’

‘Can we at least see Sickert?’ asked Daniel. He tapped his breast pocket where the letter was stored. ‘So we have something to tell the National Gallery.’

Feather hesitated, then nodded. ‘You’re lucky Armstrong’s not around or the answer would be no. But, as he’s not here, I can’t see why not. And if he asks, I’ll tell him about that letter of authority.’

‘Can we see him on our own?’

‘You certainly can,’ said Feather cheerfully. ‘That way I can say it was nothing to do with me, I wasn’t even there, I was just following instructions issued by the boss of the National Gallery.’

A short while later, Daniel and Abigail found themselves sitting at a bare wooden table in an austere interview room in the basement of Scotland Yard. Across from them on the other side of the table were two further chairs. The door opened and a uniformed constable ushered in a short, stocky man in his late thirties. He was dressed in civilian clothes that looked as if he’d slept in them, which they guessed was the case. His trousers were crumpled, as was his shirt, which was unbuttoned.

‘I’ve been told to leave Mr Sickert with you,’ the constable told them, a strong note of disapproval in his voice. ‘If he plays up, just shout. I’ll be right outside the door.’

With that, the constable left.

Sickert gave a broad smile. ‘Detective Sergeant Wilson!’ he said as he walked to the table and took one of the chairs.

‘Sergeant no longer,’ said Daniel. ‘I’m now in private practice. This is my partner, Miss Abigail Fenton.’

‘The brilliant Miss Fenton,’ beamed Sickert. ‘I’ve read about you. The famous archaeologist, and now one of the Museum Detectives, as I believe you call yourselves.’

‘We don’t call ourselves that, that’s a title dreamt up by the newspapers.’

‘Ah yes, the newspapers,’ sighed Sickert. ‘They don’t like me, you know. They call my work vulgar because it depicts real life. Real women, not those idealised depictions so loved of the Renaissance. When did you ever see a Renaissance nude with sagging breasts? I look at you, Miss Fenton, and I see—’

‘If you are going to comment on my breasts, Mr Sickert, perhaps you’ll allow me to comment on your equipment,’ retorted Abigail.

The smile was wiped off Sickert’s face and he glared angrily at Abigail, then at Daniel.

‘I do not appreciate gossip about me being spread,’ he snapped at Daniel.

‘I can assure you I have never discussed your anatomy with anyone, and that includes my partner,’ Daniel snapped back.

For a moment, Sickert seemed discomforted and confused. Then he turned back to Abigail, forcing a smile.

‘I was going to say that it would be an honour to paint your portrait, Miss Fenton.’

‘I do not appear naked for anyone except my husband and my physician,’ said Abigail firmly.

‘I do not only paint nudes,’ said Sickert. ‘You appeal to me. Your statuesque poise, your red hair.’

‘Can we get back to the matter in hand?’ said Abigail curtly. ‘You asked for Mr Wilson to try to get you released. That is why we are here.’

Sickert nodded. ‘I did not kill Anne-Marie,’ he said. ‘She modelled for me, and that was all.’ He leered as he added: ‘We may have dallied, but we were consenting adults who found pleasure in one another’s company.’

‘We’ve been told she was a prostitute,’ said Daniel.

‘She was. Women without the financial security of a husband often need to earn money that way.’

‘Not all women with husbands are financially secure,’ Abigail countered. ‘In many cases, the husband is a drain on their limited resources.’

‘True,’ admitted Sickert.

‘You paid her?’ asked Daniel.

‘For modelling for me,’ said Sickert. ‘And now and then for sex. She was fond of me and sometimes money entered into it. But I did not kill her. I could never harm Anne-Marie. Or any woman.’ He turned to Daniel. ‘You must know that from our previous encounter, Mr Wilson. You and Abberline spent long enough probing into me.’

The sound of the door crashing open and slamming against the wall made them all jerk round. The bulky figure of Chief Superintendent Armstrong stood framed in the doorway, his face purple with fury. Behind him they could see John Feather in the corridor.

‘What the hell’s going on?’ Armstrong raged.

Daniel took the letter from the National Gallery and held it out towards the chief superintendent.

‘We’ve been authorised by the National Gallery to ask for the release of Mr Sickert—’ he began, but was immediately cut off by the furious Armstrong.

‘Yes, I’ve been informed about this spurious letter …’

‘Hardly spurious,’ said Daniel. ‘It’s signed by the curator, Stanford Beckett.’

‘I couldn’t care if it’s been signed by God himself! It has no jurisdiction here. And nor have you two.’ He stepped into the room and pointed at the open doorway. ‘Get out!’

Daniel rose to his feet. ‘Legally, Mr Sickert has the right of representation …’

‘Neither you nor Miss Fenton are lawyers,’ grunted Armstrong. ‘You have no official grounds for being here, or for talking to Mr Sickert. Either you leave or I’ll have you both arrested for trespass and obstruction of the police.’

Daniel gave Abigail a look of weary resignation, and she got to her feet.

‘You are making a serious mistake, Chief Superintendent,’ she said. ‘I’m sure that Mr Beckett will wish to take this matter up with your superiors.’ With that, she turned to Sickert and gave a polite but icy nod to him. ‘Goodbye, Mr Sickert. I’m sure we’ll meet again.’

‘Not if I have anything to do with it!’ growled Armstrong.

Abigail and Daniel left the room. As they passed Feather, the inspector grabbed a quick glance into the interview room to make sure that the chief superintendent had his back to them, then gave Daniel and Abigail a conspiratorial wink, before stepping into the interview room himself.

CHAPTER FOUR

‘What did you think of Sickert?’ asked Daniel as they headed back to the National Gallery.

‘He’s an odious man. A very different kettle of fish from his sister.’

‘His sister?’ queried Daniel.

‘Helena,’ said Abigail. ‘Highly intelligent, honest, forthright, very caring about other people, unlike her brother. We were at Girton at the same time, although our courses were different. Mine was Classics, hers was psychology. She was appointed lecturer in psychology at Westfield. You may know her better as Helena Swanwick, the suffragette and campaigner for women’s rights. She married Frederick Swanwick, a lecturer at Manchester University.’

‘No, I’m afraid I don’t know her at all,’ admitted Daniel. ‘But then, I don’t move in those circles. So you don’t approve of Walter Sickert?’

‘No I don’t. He preys on women, especially lower-class women. He’s vain and a blatant self-publicist. He’s a despicable person and I don’t believe we should be helping him.’

‘I agree with you about his character,’ said Daniel. ‘That was my impression of him when we interviewed him about the original Ripper murders. But this isn’t about whether we like him as a person, it’s about whether he’s guilty of these murders, or is he being framed by someone, as he alleges. This is about justice being done.’

‘What about natural justice?’ challenged Abigail. ‘These women he’s preyed on?’

‘Who all got paid, I believe,’ said Daniel.

‘I don’t know,’ said Abigail doubtfully. ‘Are you sure he’s not using you as some kind of smokescreen? For all we know he may well have done it, but because he knows from his previous experience of you that you’re an honest person who believes in justice, he wants you as protection, and also to aid his claims of innocence.’ She frowned and gave Daniel a puzzled look. ‘What was all that about when he had a go at you for discussing his equipment? He seemed really angry.’

‘When we brought Sickert in for questioning during the Ripper investigations, the guv’nor had the idea of giving him a medical examination, and we discovered that his penis was disfigured. It was a congenital defect. Not that it seemed to stop his sexual adventures.’

‘And he thought that was what I was referring to?’

‘Yes,’ nodded Daniel. ‘He’s very sensitive about it.’

‘I hope he was reassured that you hadn’t spoken about it to me. I was just getting back at him for presuming he could talk to a woman about her breasts.’

‘We don’t know he was going to say anything about your breasts,’ said Daniel. ‘You didn’t give him a chance to finish what he was saying.’

‘Why raise the subject if he wasn’t going to continue it?’ asked Abigail.

‘Yes, good point,’ admitted Daniel. ‘And Sickert’s perfectly capable of raising subjects like that, just to shock. He likes shocking people, which is why he’s quite proud of the fact that some people see his work as vulgar.’

Stanford Beckett was waiting for them when they arrived back at the National Gallery. Regretfully, they told him their mission had not been a success.

‘We saw Mr Sickert, who seemed to be in good spirits, but we were ordered off the premises by Chief Superintendent Armstrong. I’m afraid he seems extremely reluctant to release Sickert.’

Beckett gave a weary sigh. ‘I’m sorry you had an abortive journey,’ he said apologetically. ‘But I’ll arrange payment for your time on your usual terms. I hope that will be acceptable?’

‘Very acceptable,’ said Daniel.

They left the gallery and began their walk up Charing Cross Road towards Camden Town.

‘Well, that’s that,’ said Abigail resignedly. ‘I didn’t like Sickert, but it’s a great pity that he remains in custody of that oaf Armstrong, who I’m sure will try and break him down and confess.’

‘Oh, I’m not sure if that’ll be the end of it,’ said Daniel. ‘From our point of view, yes. But Ellen Sickert isn’t the sort of woman to give up her husband that easily.’

Chief Superintendent Armstrong paced around his office as Inspector Feather scribbled down his superior’s instructions.

‘Anne-Marie Dresser’s movements,’ he said. ‘We need to find out who she saw the night she was killed. Who she was planning to see. Talk to her friends. Neighbours. Find out if any of them saw Sickert near that room of hers during the evening.’

‘He says he was at home the whole time, and that his wife will bear that out,’ pointed out Feather.

‘Balderdash!’ snorted the chief superintendent. ‘A wife’s alibi isn’t worth anything.’

‘He says his servants will back it up. And there’s this character …’ He flicked back through his notebook. ‘Edwin O’Tool.’

‘A complete figment,’ derided Armstrong. ‘Sickert’s the one. All we’ve got to do is break his alibi, and we do that by proving he and this woman Dresser saw one another that night.’

There was a loud and imperious knock at the door. Before Armstrong could say ‘Come in!’, the door had been pushed open and the tall and bulky figure of Sir Bramley Petton was framed in the doorway. Petton was a very well-known barrister, possibly one of the most familiar faces at the Old Bailey. He was in his sixties, with a mass of unruly greying hair, and a large stomach that battled to burst out of his very expensive tailor-made suit. He carried a bulky envelope under one arm. Petton eyed Armstrong and Feather with a glinting and accusing glare, developed over many years interrogating witnesses in the highest courts in the land.

‘Chief Superintendent Armstrong,’ he boomed, his voice filling the office.

‘Indeed, Sir Bramley,’ said Armstrong. ‘What can I do for you?’

By way of answer, Petton dropped the bulky envelope on Armstrong’s desk.

‘You can release my client, Mr Walter Sickert.’

Armstrong stared at the barrister, bewildered. Petton pointed at the large envelope he’d just deposited.

‘These are signed affidavits from Mrs Ellen Sickert and four of the servants of the Sickert household which swear to the fact that Mr Walter Sickert was at home during the evening and the night of the 14th February, when this heinous crime was committed. Also, there was one Edwin O’Tool, a carpenter, who Mr Sickert had invited to celebrate with him. They drank copiously and Mr O’Tool was obliged to stay the night on the floor of the Sickert’s drawing room next to the settee. Mr Sickert occupied the settee. If Mr Sickert had got up during the night, he would have trodden on Mr O’Tool and woken him. Ergo, Chief Superintendent, my client did not and could not have been murdering and disembowelling anyone that night. Therefore, I insist you release him from custody. Failure to do so will result in my presenting these affidavits to the police commissioner and the home secretary for them to authorise his release.’

Armstrong fixed the barrister with a grim look.

‘There was absolutely no reason for this overreaction—’ he began.

‘Overreaction!’ exploded Petton.

‘… because I had already decided to release Mr Sickert. Is that not so, Inspector?’ he said, turning to Feather.

Feather looked at him in awkward surprise, then at Bramley Petton, before saying, ‘Yes, sir.’

‘But by all means leave these affidavits here,’ continued Armstrong. ‘They may contain evidence that will help us in our investigation.’

Petton gave him a withering look and gathered up the envelope. ‘These are the property of our firm,’ he said. ‘If you decide to take Mr Sickert into custody again, then, and only then will they be relinquished to you. I look forward to my client being released and brought to me.’

Armstrong swallowed, then turned to Feather.

‘Inspector, have Mr Sickert released and taken to the reception area.’ He turned to Petton. ‘You may collect him there, Sir Bramley.’

CHAPTER FIVE

‘Why was Sickert a suspect in the first Ripper investigation?’ asked Abigail.

The pair had arrived home and it was Daniel’s turn to prepare food for them. At first Abigail had been suspicious of his offer because Daniel’s favourite meal seemed to be pie and mash from the local pie and mash shop, but today he’d used the range to roast potatoes and a chicken, which they were eating now, along with a glass of beer each.

‘For the same reason he’s a suspect now,’ replied Daniel. ‘You said yourself, as well as his society portraits, he also paints women from the lower classes, often prostitutes.’

‘More than paints them,’ she said scornfully.

‘Yes, we did find that he also enjoyed their favours.’

‘But, as you pointed out to me earlier, that doesn’t make him a murderer,’ she admitted.

‘No. But rumours came to us that he and a friend of his used to take nocturnal trips to Whitechapel, and that some of these trips had occurred when the murders were committed.’

‘Who was the friend?’ asked Abigail.

‘Prince Albert Victor Christian Edward.’

‘The Queen’s grandson?’ said Abigail, shocked.

Daniel nodded.

‘But jaunts like that mean nothing!’ said Abigail, recovering her composure. ‘You’re surely not saying that the Queen’s grandson, and heir to the throne …’

‘Second in line,’ Daniel corrected her. ‘His father, the Prince of Wales, is the immediate heir.’

‘There’s no need to be pedantic,’ said Abigail irritably. ‘You know what I’m saying.’

‘That we shouldn’t suspect him because of who he is?’

‘No, I’m not saying that.’ Then she gave a rueful sigh. ‘Yes, I suppose I am. But he died, didn’t he?’

‘Five years ago, in 1892 at the age of 28. Pneumonia.’

‘Very convenient,’ said Abigail tartly. ‘But that was four years after the murders, so I assume you couldn’t find any evidence against him. Or against Sickert.’

‘Actually, the decision not to proceed wasn’t that straightforward, even though we learnt that on 30th September 1888, the day that Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes, two of the Ripper’s victims, were killed, Prince Albert was 500 miles away at Balmoral, so he couldn’t have been involved. But there were questions about the dates of the other murders. Mary Ann Nichols was killed on 31st August. Annie Chapman was killed on 8th September. Mary Jane Kelly was killed on 9th November.’

‘But no one was ever charged with the crimes, so I assume you had no proof against Prince Albert Victor or Sickert.’

‘We never had the chance to dig deeper into them, although my guv’nor wanted to. At that time Armstrong was a chief inspector, and he stepped in and told us that the powers that be didn’t want any further investigations into Prince Albert Victor, Walter Sickert or Sir William Gull.’

‘Sir William Gull?’ queried Abigail.

‘He was the third member of the alleged conspiracy. Rumours said that all three were involved in these nocturnal trips to Whitechapel, and were involved in the killings. We had eye-witness reports that Sir William’s carriage, which was quite distinctive with a coat of arms on it, was seen in Whitechapel on the night of at least two of the murders.’

‘Why wasn’t he investigated?’

‘We talked to him, but then we were warned off. Sir William Gull just happened to be the personal physician to the Queen. Gull died in 1890.’

‘Abberline retired from the police, didn’t he?’

‘He did, in 1892, a year before I did. The same year that Prince Albert Victor died.’

‘Did Sir William Gull and Prince Albert Victor also get a medical examination, like Sickert?’

Daniel smiled. ‘No chance. We were only allowed to talk to Sir William briefly before the shutters came down. And we were barred from meeting the prince.’

‘Why did Armstrong interfere?’

‘To protect the good name of the royal family.’ He gave a scowl as he added: ‘It was surely no coincidence that, shortly after, Armstrong was promoted to superintendent.’

‘A reward for quashing the investigation?’

‘That’s what Fred Abberline thought. It was also around the same time, in 1889, there was another scandal involving Prince Albert Victor: the Cleveland Street Scandal.’

‘You’ve mentioned that before. Wasn’t it a homosexual brothel?’

‘It was. Fred Abberline and I were called into investigate. We discovered that telegraph boys were being used as homosexual prostitutes at a house in Cleveland Street, but when we moved to make arrests, we only managed to get hold of one man who was involved, the house was empty. But we found a list of clients, many of them very well connected.’

‘Prince Victor again?’

‘Someone from his household, and some others he was known to associate with.’

‘What happened in the end?’

‘Most of the clients whose names were on the list fled abroad.’

‘So no one was charged.’

‘No one of any social importance. A few lesser individuals were arrested, including some of the telegraph boys, who received light sentences.’

Abigail frowned. ‘What I don’t understand,’ she said, puzzled, ‘is if Armstrong quashed the investigation into Sickert, the Prince and Gull nine years ago, why is he arresting him now over this one? Surely he runs the risk of raising why Sickert was let off the hook the first time, which will call his position into question.’

Daniel chuckled. ‘What do you think of Sickert?’ he asked.

‘I’ve already told you,’ said Abigail, her face tight with her disapproval. ‘He’s an odious man. Vain and despicable.’

‘Exactly,’ nodded Daniel. ‘And it’s been his vanity that’s been his downfall here. After our original investigation was ended, Sickert took delight in boasting to his friends that he was untouchable. That the police kept their hands off him because he “knew things”. The implication was that he had something on Armstrong. Being Sickert, he was clever not to repeat that too often, but word got back to Armstrong, and the superintendent was angry. No – more than angry, he was incandescent. But what could he do? Sickert hadn’t actually said anything specific, just hinted that he couldn’t be touched. And, so long as he didn’t do anything illegal, he couldn’t be. He may be disreputable, a lecher, a frequenter of prostitutes, but none of that’s illegal. And all the time Armstrong simmers over the injustice of what he knows Sickert has said behind his back. So now, this is revenge. This is something he can pull Sickert in for. And it’s not just about Sickert, it’s a message to people like Bram Stoker, for example. You know the animosity there is between Armstrong and Stoker.’

‘Stoker? How does he come into it?’

‘He and Sickert are old friends. Years ago, Sickert was an actor at the Lyceum in Irving’s theatre company.’

‘My God! I’ve always thought it was a small world, but it just got smaller. Sickert, Stoker, Irving and Armstrong?’

‘I know,’ said Daniel. ‘There are lots of long memories involved here.’

There was a knock at their front door.

‘I’ll go,’ said Daniel, getting to his feet.

Abigail heard voices from the front door, then Daniel reappeared with a brown envelope similar to the one that had been delivered to them that morning. This one had been opened.

‘It was a messenger from Stanford Beckett,’ Daniel said.

He held out the single-page letter to her.

‘Dear Mr Wilson and Miss Fenton,’ she read. ‘Walter has been released from custody and asks if you can meet him here at my office tomorrow morning at 10 a.m.’

‘I told the messenger to tell Beckett that we’d be there,’ said Daniel. ‘I hope that’s all right with you.’

‘How did he come to be released?’ asked Abigail, stunned. ‘Armstrong was so determined to keep him.’

‘But I expect Ellen Sickert was even more determined to get him out,’ said Daniel. ‘As I said, she is a formidable woman.’

CHAPTER SIX

John Feather could see that Chief Superintendent Armstrong was still seething with anger when he arrived at Scotland Yard the following morning.

‘Have you found anything?’ demanded Armstrong angrily. ‘Anything that puts Sickert with the victim that night?’

‘No, sir,’ said Feather. ‘I went to the room she had at Cumberland Market and spoke to her neighbours, but none of them recall seeing her that night. They believe she was out. And none of them saw any men around her room, certainly none answering Sickert’s description. And most of the neighbours knew Sickert, because he was a frequent visitor.’

‘So maybe he’d arranged to see her somewhere else, away from her room?’ suggested Armstrong.

‘There’s always the possibility that whoever wrote that note accusing Sickert did it because they had some kind of resentment against him, not because they actually knew anything,’ said Feather.

‘No!’ growled Armstrong. ‘It’s Sickert. I feel it in my bones.’ He banged his fist hard on his desk. ‘How does he do it? How does he get to use people like Sir Bramley Petton? He’s not cheap, you know. And for Petton to come here himself, not just send a solicitor …’ He shook his head, lost for words. ‘I doubt if there were even any affidavits in those papers. A lawyer’s trick. I’ve seen him in court pulling that kind of stunt.’ He looked at Feather as he asked: ‘Did you put a tail on Sickert like I said?’

‘Yes, sir, I did that first before I went to Cumberland Market. There was a note from him waiting for me at the reception desk just now.’ He took a piece of paper from his pocket. ‘Subject arrived at National Gallery at 9.45 a.m.’

‘Back to the scene of the crime,’ growled Armstrong.

‘D Wilson and A Fenton arrived ten minutes after,’ continued Feather.

‘What?!’ bellowed Armstrong, leaping to his feet. He reached out and snatched the piece of paper from Feather’s hand. ‘What’s going on?’ he demanded.

Daniel and Abigail sat in Stanford Beckett’s office and studied Walter Sickert, who lounged in a leather armchair beside Beckett’s desk. They’d gone through the usual formalities, handshakes and polite smiles, when they first walked in, before settling themselves down.

‘Congratulations on your release,’ said Daniel. ‘There’s been no mention of it in the press, but I assume Chief Superintendent Armstrong changed his mind about your guilt.’

‘Alas, no,’ said Sickert. ‘Fortunately for me, Sir Bramley Petton, the eminent barrister, turned up at Armstrong’s office with a pile of affidavits from my wife and my servants, all swearing that I was at home the whole night of February 14th. There was also one from an acquaintance of mine, a Mr Edwin O’Tool. He and I indulged in a little too much alcohol on the evening and as a result I spent the night on the settee in the drawing room while Mr O’Tool slept on the floor next to the settee. He gave a statement that said I could not have got up and left in the night without treading on him and waking him. As a result, Armstrong was reluctantly forced to let me go.’

‘He doesn’t believe the statements?’

‘No, he doesn’t. And I have to admit, if I were in his shoes, I would have doubt about them. One’s wife and servants would be expected to say I was at the house all night, and Mr O’Tool has issues with drink that could make him a suspect witness.’ He smiled. ‘But, faced with the eminence of Sir Bramley, the chief superintendent had little choice but to release me. However, I’d like to hire you to prove my innocence.’

‘The police will already be investigating.’

‘I doubt it. I believe that Chief Superintendent Armstrong is convinced I’m guilty, so he’ll be spending his time waiting for me to make a slip that will give me away. He’s already got his bloodhounds trailing me. There was a constable outside my house this morning and he accompanied me all the way here. I expect he’ll be waiting outside when I leave.

‘In the meantime, in the eyes of everyone, I’m guilty and getting away with it. And I’m sure that Armstrong will be keen to remind people – in some oblique way – that I got away with it before, in 1888. My reputation, and therefore my living, is at stake as long as this hangs over me. I have many portraits commissioned, and already people are backing off from going ahead. Will you take on this commission on my behalf and find the real guilty person?’

Daniel shot a look at Abigail, who hesitated, then nodded. ‘We will,’ she said.

‘How will you begin?’ asked Sickert.

‘First, we’d like to talk to your wife and servants, and also see these affidavits,’ said Daniel.

‘You do not trust my wife and me?’

‘It’s not a question of trust, it’s a matter of looking at everything that’s germane to the case. If we are to prove your innocence, the first thing we need to do is assure ourselves that you are, indeed, innocent.’

‘Very well,’ Sickert nodded. ‘I’ve already let Nellie know that I hope to engage you, so she’ll be expecting you. I’ll also tell Sir Bramley to let you see the affidavits. When will you call?’

‘Later today?’ suggested Daniel.

‘That will be fine. I shall depart for Venice tomorrow, as I originally intended.’

‘Does Chief Superintendent Armstrong know you intend to leave?’

‘He may do,’ shrugged Sickert. ‘He knows I was on my way to Venice when they took me into custody.’

‘He may not let you go.’