6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

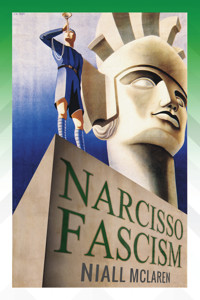

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book examines the biological, social and psychological influences driving one of the most important, and frightening, trends in modern international politics, right-wing extremism. It is radically unlike anything written on the topic before and its conclusions should make all of us stop ... and worry about the world we are leaving to our children. Niall McLaren is a recently-retired Australian psychiatrist with a particular interest in the application of the philosophy of science to psychiatry. Of this work, Prof. Alan Patience, of the School of Social and Political Sciences, Melbourne University, said:"Niall McLaren's new book weaves the disciplines of psychiatry and political science into a highly original approach to the political psychology of fascism... (His) book takes the analysis of fascism to another level, warning how genetically and psychologically ingrained the fascist urge is in human nature generally. In revealing this with rare clarity, this book will help counter the deeply disturbing drift towards neo-facism across the contemporary world."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 404

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Narcisso-Fascism: The Psychopathology of Right-Wing Extremism

Copyright (c) 2023 by Niall McLaren. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 978-1-61599-754-1 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-755-8 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-756-5 eBook

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

Tollfree 888-761-6268

Distributed by Ingram Media Group (USA, CAN, EU, AU, UK)

The interconnexion between sadism, masochism, success-worship, power-worship, nationalism and totalitarianism is a huge subject whose edges have barely been scratched … All of them are worshipping power and successful cruelty. It is important to notice that the cult of power tends to be mixed up with a love of cruelty and wickedness for their own sakes.

George Orwell.

Raffles and Miss Blandish (1944),

in The Decline of the English Murder and other essays.

(Emphasis in original)

Also by Niall McLaren

Anxiety—The Inside Story: How Biological Psychiatry Got it Wrong

Title Available

The Mind-Body Problem Explained: The Biocognitive Model for Psychiatry

A (Somewhat Irreverent) Introduction to Philosophy for Medical Students and Other Busy People

Humanizing Psychiatrists: Toward a Humane Psychiatry

Humanizing Psychiatry: The Biocognitive Model

Humanizing Madness: Psychiatry and the Cognitive Neurosciences

Humanizing Madness: Psychiatry and the Cognitive Neurosciences

Contents

Preface

Chapter 1: The idea of narcissism.

1.1: Why narcissism?

1.2: Lights. Cameras. Bring on the narcissists.

1.3: Narcissism is as narcissism does.

1.4: Fear: the intolerable spur.

1.5: Conclusion: Le narcissique, c’est moi.

Chapter 2: The idea of fascism.

2.1: Whence fascism?

2.2: Essence of fascism.

2.3: The fascist society.

2.4: Fascism: A case study.

2.5: Conclusion: Fascism Prêt-à-Porter.

Chapter 3: The idea of dominance.

3.1: Testosterone and birds.

3.2: Testosterone and humans.

3.3: Testosterone and social dominance.

3.4: When dominance becomes dysfunction.

3.5: Conclusion: The challenge of human biology.

Chapter 4: The idea of control.

4.1: That’s not narcissism, that’s show business.

4.2: That’s not narcissism, that’s religion.

4.3: That’s not narcissism, that’s the military.

4.4: That’s not narcissism, that’s authority.

4.5: Conclusion: The mania of control.

Chapter 5: Facets of fascism.

5.1: Boys will be boys.

5.2: Lies will be told.

5.3: Don’t tread on me.

5.4: “Socialism is slavery.”

5.5: Even the hoax is a hoax.

5.6: Fools, fiends and follies.

5.7: Conclusion: The kaleidoscope of fascism.

Chapter 6: Fascism, illusion and reality.

6.1: Fascism’s rise.

6.2: Fascism’s enablers.

6.3: Fascism’s fall.

6.4: To create fascism: Let the Left beware.

6.5: To end fascism.

6.6: Conclusion: Fascism, the unstable pyramid.

Chapter 7: Defanging fascism.

7.1: Fascism as a political cycle.

7.2: The fascist appeal.

7.3: Fascism as religion and vice versa.

7.4: Conclusion: “This machine kills fascists.”

About the Author

Index

Preface

Since about 1980, across a very large part of the world, the political spectrum has undergone a major shift to the right. In the early post-war period, most developed nations were committed to centrist or mildly left-of-centre domestic and international policies, including state-sponsored industrial policies, major public infrastructure projects, and creating welfare states to reduce inequality. Today, however, we see country after country embracing harsh “neo-liberal” policies. The ultimate goal here is restricting state-provided services for those who don’t pay much tax, meaning the poor, in order to reduce the taxes paid by those who feel they pay too much, meaning the rich. At the same time, country after country has been adopting aggressive “anti-immigrant” policies, designed to make life difficult for outsiders, often to the point where they can’t enter the country or are driven to leave.

In theory, neoliberalism would consist of limiting the welfare state and privatising national services but, in practice, we see state assets sold cheap to the best-connected bidders, accelerating militarism of foreign policies, militarisation of police and custodial forces, and the ever-widening reach of internal and external spying agencies. Hand in hand, there is relentlessly rising corruption and increasing destruction of the natural environment, while the drive to reduce inequality has gone into reverse. Between 1978 and 2021, real (inflation-adjusted) pay for US workers increased by 18%; the income of their CEOs, by contrast, increased by an astounding 1,460%. The irony is that, in most cases, this has been done by governments elected for the express purpose of restricting state benefits and generally making life more difficult for the very people who voted for them.

Is this apparent burst of mass irrationality an accident of history? I don’t believe so. The purpose of this book is to show how the contemporary “stampede to the right” is the predictable result of unscrupulous politicians exploiting particular, poorly understood biological, psychological and socio-political themes or drives. We need to understand these drives, to tell when we are being manipulated so we can control them before they destroy us.

This work is offered as an exploration of some ideas, the intention being to start a debate by clarifying the forces that drive apparently sensible citizens to embrace extremist and self-destructive politics, and to vote against their own interests. It is based in the theoretical framework developed in author’s model of mental disorder, the Biocognitive Model for Psychiatry [1]. The purpose is first, to demonstrate the broad applicability of that model and second, to explain disturbing political trends in the modern world.

Readers may ask: Do we need another book on fascism? The short answer is yes, because fascism hasn’t gone away. Various writers have offered their views on how and why fascism arises. Looking at all the information available, they have tried to assemble a coherent account of the causes of extremism by “joining the dots.” This is like people looking at the starry sky and seeing particular images. One person looks up and says he can see an image of a mighty warrior smiting his enemies’ heads off, another sees a sleeping elephant while a third just sees stars. This very human tendency, of seeing patterns in what are essentially random, nebulous or neutral fields, is known as pareidolia. So one author looks at the recent history of fascism and sees compulsive German perfidy, at which a lot of people settle back with a relieved sigh, secure in the belief that “It can’t happen here.” 1 Another looks at the same evidence and sees corruption and incompetence among the elite, quite forgetting that massed storm troopers don’t come from the elite. A third person sees the clearest picture of the work of supernatural forces of evil which can only be countered by everybody falling on their knees and praying.

This book’s intention is to look at much the same evidence and draw an entirely different picture, one which goes beyond description, to explanation and thence, if all goes well, to prediction. As a psychiatrist, I see things from a particular point of view, but most definitely not the way modern psychiatry locates the cause of mental disorder as a genetic defect in the individual. Thus, people looking at, say, the life of Adolph Hitler, will often say “He was sick, he was schizophrenic,” as though that explains it all. No, he wasn’t but, even if he were, it wouldn’t explain why his followers acted as they did. That sort of “explanation” tries to shift the locus of responsibility to one person and is little more than pseudoscience. Instead, I will look at contributing factors on three levels of explanation, the biological, the psychological and the level of society itself.

First, I should point to a problem for anybody researching this field, that the very words themselves have been so misused over the years that they now mean more or less whatever anybody wants them to mean. The first step, therefore, is to clarify just what all these terms mean and to explain how they will be used. This will occupy the first three chapters. Chapter 1 looks at the psychology of certain personality types, particularly that known as the narcissistic personality disorder and its relation to psychopathy, and concludes by considering the role of fear in human behaviour. Chapter 2 will look at the political phenomenon known as fascism. In Chapter 3, we will approach the features described in Chapter 2 via a biological framework. The rest of the book brings these themes together, with the intention of building a coherent theoretical program by which we can start to reverse our lemming-like rush to the far right.

Nobody should think change will be easy. As will become apparent, anybody who wishes to change the direction of society will be declaring war on the darkest forces in the human mind. This way could be dangerous, but doing nothing will surely be more dangerous.

References:

1.McLaren N (2021) Natural Dualism and Mental Disorder: The biocognitive model for psychiatry. London: Routledge.

________________________

1 This is the title of a novel by Sinclair Lewis, which shows that it can.

Chapter 1: The idea of narcissism.

I am the only person in the world I should like to know thoroughly.

Oscar Wilde

1.1: Why narcissism?

Several years into my training in psychiatry, when a psychologist told me that all psychiatrists are narcissistic, I had to make a quick trip to the library to understand what he meant. According to Google Trends, mentions of narcissism have been rising steadily since 2004 with, interestingly, a peak in 2013-14. Very often, it isn’t clear what people mean by it, except that it isn’t complimentary. However, whenever we use the word, it is essential to remember that it refers to a personality type. It does not mean mental disorder/illness/disease etc.

The word originates with the Greek myth of the beautiful youth who caught sight of his reflection in a pool and was so smitten with his image that he sat staring into the water until he wasted away. In psychology, it has come to mean excessive self-interest to the point where it dominates and controls the individual’s life. Naturally enough, as part of the normal personality, we all need to have some concern for ourselves, some level of self-regard, but normality is a broad range, not a point. There is no cut-off point separating normal from pathological; at its edges, normal self-interest merges imperceptibly with excessive self-involvement.

What we class as “normal” varies tremendously, from one culture to the next, the age of the individual, the gender, occupation, intelligence, and so on. Another point is that self-interest varies over time. The bridal couple at a wedding reception will be much more self-aware (and entitled to be on their big day) than an elderly relative seated at a distant table. Sick people, especially people in pain, tend to be more self-aware because they know how easily they can be hurt or how reliant they are on other people to satisfy their needs. At the same time, there is a huge variety of ways people can indulge their hobby of losing themselves in themselves. All this means there is no firm definition of “normal self-involvement,” and no fixed rules on what is or is not acceptable behaviour. For somebody of my generation, the modern habit of putting hundreds of photos of yourself on the internet is appalling. To us old folks, posing for an unnecessary photograph, even the word “selfie” itself, is just cheap showing off.

Why would anybody show off? Clearly, we are talking about two different things, the observable behaviour, and the underlying personality that generates the behaviour. Personality precedes the behaviour, and we can define it as:

… the total set of explicit and implicit mental rules (including attitudes, beliefs, etc) that generates the uniquely distinguishing habitual patterns of interaction between the healthy, sober individual and her environment, in the stable adult mode of behaviour.

That is, personality amounts to the set of rules you have acquired over your lifetime that govern what you do, how you do it and how you react to the world. As such, personality is essentially no different from any other set of rules in your life, such as the rules governing your accent, your likes and dislikes or, indeed, a sporting game, except you don’t “learn” your personality the way you learn football or tennis. Starting very early in life, we acquire these rules through daily experience, some of it good, some bad. There certainly isn’t a single place in your head where all these rules reside although most of them seem to be clustered in the frontal regions. Thus, frontal brain damage typically produces “personality change.”

Depending on their content, rules tend to cluster in groups so that people who are fussy about cleanliness and tidiness also tend to be fussy about punctuality and order. Those who don’t trust their neighbours are also likely to be suspicious of authority or will see innocent mistakes as evidence of plots and conspiracies. These clusters are known as traits, and while psychology once thought personality traits were determined by genetics, there is very little evidence for it. Overwhelmingly, we are the products of our upbringing, including home, school, playground and workplace. Personality is more or less fixed by about age eighteen to twenty but change is still possible. People can improve if life goes well and they set their minds to it but, all too often, following bad life experiences in adulthood, things can get worse.

Very often, the most important rules are not fully conscious, perhaps because they were learned early in life, even preverbally, or they are what we call implicit learning rather than explicit. This allows us to see the difference between normal and abnormal personality:

An ordered or normal personality is said to exist when the individual’s set of rules is both internally coherent, thus generating a euthymic (pleasant) state, and consistent with the larger society’s set of rules, thus leading to harmonious and productive interactions.

Personality disorder exists when either the individual’s set of rules is internally incoherent, causing inner distress (episodic or persistent), or when it repeatedly brings him into conflict with his social environment, resulting in distress in the individual and/or society, or all of the above.

Full-blown narcissism is a personality disorder, as in “Oh, don’t don’t take any notice of him, that’s just how he always is,” rather than a recent change, as in “She’s always been such a happy and caring person, I don’t know what’s come over her.”

A narcissistic personality disorder is a lifelong pattern of abnormally self-involved behaviour which causes inner conflict and personal distress, and leads to friction with the social environment.

Unfortunately, modern society notices the self-involved and tends to reward them while neglecting the quiet workers who actually keep the business of life turning over.

One of the earliest authors to promote the concept of narcissism was Sigmund Freud, the Viennese neurologist who developed the psychological theory known as psychoanalysis. While over the past forty years or so, Freud’s work has largely faded from view, it was immensely influential in the middle part of the last century. It dominated not just psychiatry and psychology, but also the public idea of what the well-educated person should be able to talk about. Many psychoanalytic terms crept into everyday language, mostly wrongly. To Freud, excessive preoccupation with self was a sign of arrested psychological development resulting from poor relationships with the parents and significant others.

As a primary psychological disorder, the narcissistic personality could be treated by psychological methods, meaning talk therapy. Freud’s method consisted of one-hour sessions each day, during which the patient was encouraged to talk about himself, week after week, for years. Was it successful? That depends on who you ask but the notion that insatiable involvement in self can be cured by encouraging the “sufferer” to become more self-involved is counterintuitive. Be that as it may, only the wealthy and self-indulgent could afford the time and money for Freudian psychoanalysis, so analysts probably didn’t do much damage, either.

Since the decline of Freud’s theories, psychiatry has adopted a biological approach to mental disorder. The standard view is that mental disorder is just a special case of brain disorder in which mental symptoms predominate. That is, the final explanation for mental problems consists of a statement about the patient’s physical brain. Psychology doesn’t get a mention. As part of the biological push, modern psychiatry has adopted the categorical concept of mental disorder, meaning that each and every mental disorder is a separate category of illness. While they may be similar in clinical presentation, it is claimed that the different diagnostic categories are fundamentally different at the level that counts, the level of brain function. Mostly, this is taken to mean at the level of neurotransmitters, the chemicals that transfer messages from one neuron to the next through the brain’s indescribably complex neural pathways. In this biological view, since the cause of mental disorder is physical, it follows that treatment should also be physical. Thus, people who see a psychiatrist about feeling worried or depressed will be told “You’ve got a genetic chemical imbalance of the brain, take these tablets and come back in a month. They will make you feel better but they won’t change your genes. You have to learn to live with your disease.”

By the same view, a person who suffers severe anxiety, which causes him to lose his job, which leads to depression, will be told he has two separate chemical imbalances of the brain so he needs more drugs. If he starts to worry about making mistakes because of feeling drugged, that’s another disorder which needs its own drugs; if he gets irritable and needs a drink, that’s two more to be treated, and so on. It is not uncommon to see people with a dozen or more distinct diagnoses, taking up to ten different psychiatric drugs, usually in what are politely called “heroic dosages.”

Why would anybody bother with such a complex system? Surely it is clear that mental problems can have causes in life, that depression, for example, is a reaction to life events? The answer is that each distinct diagnosis is assumed to have a separate biological cause, for which there should be a separate and specific drug treatment. The categorical approach to mental disorder justifies vast expenditure on drug research and treatment.

Personality disorder is a little different. Firstly, modern psychiatry only accepts a limited number of distinct personality disorders – currently ten – so one person can easily meet the criteria for half a dozen separate personality diagnoses. Second, there is no scientific evidence to say that any of this is true. Personality factors do not fit a categorical model as all personality traits are dimensional, meaning they range in a continuous line from normal to the wildest extremes. Third, there is no reason to believe personality is a biological phenomenon and every reason to believe it is wholly a matter of psychology. Finally, mainstream psychiatry has no treatment to offer. Psychiatrists no longer offer psychotherapy, and their drugs don’t work on personality; if they did, we would put them in the water supply.

My view is that the whole concept of personality disorder in modern psychiatry is a complete mess [1]. It is an artefact of psychiatry’s desperate need to squeeze all mental disorder into a biological model, a house of cards built on sand and held up by the skyhook of artful manipulation of the concept of personality traits. Personality disorder is both common and troublesome but psychiatrists have no approved method of treating it. However, since psychiatrists make their living from treating people (prescribing drugs), not by telling them to go away and live with it, mainstream psychiatry is now engaged in a long-term program of reclassifying people with personality disorders as mentally ill and putting them on drugs [2]. This quietens the worst of their complaining and difficult behaviour, because that’s what psychiatric drugs do, and it means the newly-minted mental patients have to keep coming back for treatment in the very long term. Problem solved.

But back to narcissistic personality disorder: who are these people and why should we bother with them? The answer is that while there is no such thing as a narcissist, and no such thing as narcissism, the behaviour which constitutes the narcissistic trait is universal. We all show behaviour of the self-regarding type, the only question is the extent. However, the trouble with self-regard is that it readily links forces with other, more destructive personality characteristics and the combination quickly spirals out of control. Abnormal personality traits amplify each other so that, in one person, behaviour which is a bit of a nuisance or even amusing can, in another individual, suddenly explode to produce major disturbance. And that is the central theme of this essay: while narcissistic behaviour in isolation varies from amusing to a nuisance to self-damaging (i.e. at its worst, it is a problem for the individual and his “significant others”), when combined with other, destructive human characteristics, it becomes exceedingly dangerous. We need to understand this point and deal with it as a matter of urgency.

1.2: Lights. Cameras. Bring on the narcissists.

In talking about human behaviour, we need to avoid stereotypes, but... as shown by the opening quote from Oscar Wilde, one of history’s most famous narcissists, it’s hard to avoid stereotyping people who want to be seen as stereotypes. Or, as George Orwell said of the surrealist artist, Salvador Dali, “His autobiography was simply a strip-tease act conducted in pink limelight.” So while I would prefer not to mention “those narcissists” or talk about “their narcissism,” I will sometimes do so but remember, it’s just a figure of speech.

The key to understanding narcissistic behaviour is to remember that the subject is living life as an act in which he is writer, producer, director, lead actor and adoring audience, all at once. We will talk about the essential features of the narcissistic personality disorder, then look at some examples.

The central point or core of the personality type is self-absorption: everything else flows from this. Oscar Wilde again: “I am always astonishing myself. It is the only thing that makes life worth living” (remember that half of what he said wasn’t serious but nobody, least of all himself, knew which half to ignore). Narcissism means believing that my feelings are always more interesting and more important than yours, that my opinions trump yours or my needs take priority over yours. All of this has to be seen in its context: for example, the professor’s opinion is more likely to be right than yours; or the experienced gardener who says your choice of plant isn’t suitable for the soil is more likely to be right but, since you’re paying, you can have what you want. However, if you say you’re unhappy with something that I want to do, it’s not enough for me to tell you to stop being a spoilsport. You may actually be right but, for the committed narcissist, that possibility doesn’t arise: “I’m an interesting person but you’re boring. Nobody wants to hear your dumb opinions so keep quiet and listen to me.”

Very often, via the lust to be the undisputed centre of attention, self-absorption comes across as a need to dominate and control. It’s just not possible to have two centres of attention in the same room, it interferes with the endlessly fascinating drama of self-glorification. The narcissistic personality (aka narcissist) wants to take control to make sure nobody else gets a foot into the limelight, that he gets the best and most interesting of whatever is going as he deserves it because he is the best and most interesting person at the party. He wants to be president of the local sports club, not the secretary and certainly not treasurer because that’s dull and involves too much work. He wants the best clothes, the biggest car, the fastest motorbike or the flashiest house. He should have the corner office, he should meet the visiting bigwigs or have the lead role in the play. Partly this is his sense of superiority – he firmly believes he is the best – and partly it’s a need to nobble the competition. As the writer and supremely-polished narcissist, Gore Vidal, said: “Success is not enough. One’s friends must also fail.”

However, in tandem with the drive to take control is a total lack of interest in the hard work of actually running something. Narcissists quickly lose interest in a job as it distracts from the most important thing in life, I, me, myself. They will undertake all sorts of machinations to get the position that brings the most attention but they don’t actually want to do the work. They’re a bit like a dog chasing a bus: if he catches it, he wouldn’t know what to do with it. It’s not that they can’t attend to detail, it’s just that they only attend to details they find interesting, meaning detail that relates to them, such as clothes, makeup, who sits where, who stays in the best hotel, on and on. When the detail involves them, they micromanage to the point of driving everybody mad but, when it doesn’t, they brush it off and leave it to somebody else. If something goes wrong, they blame somebody else. All too often, this leads them to deception and even outright crime as they try to cover up their failings. One offence leads to another, and another, until one day the whole thing falls in a heap. Then everybody says: “Who would have expected that? He’s the last person I would have suspected.” That’s because he has been so successful in distracting people from his real self.

The darker side of the need to take control is suspicion: “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.” The true narcissist is always worried that somebody will come through the door wearing something more dramatic, or arrive in a bigger car, or have a prettier girlfriend on his arm or a more muscular arm to support her. He is never sure that people are being genuine or that they aren’t planning to rush off to meet somebody else. He is constantly on the lookout for something better or for signs of competition, and he assumes that everybody else is the same. Mistrust is typical of the personality disorder but it can blur across to frankly paranoid thinking, especially under pressure, such as facing arrest or through alcohol and drug abuse.

This is important: mainstream psychiatry says that true paranoid thinking is only seen in paranoid personality disorder but, again, this is false. We are all suspicious to some extent, we have to be otherwise we would be robbed blind in a few hours. I always lock my house and my car, my passport is kept in a safe unless it’s in my hand, I don’t write down passwords of any sort, and so on. But we don’t call that suspicion, we call it prudent care except nobody knows where normal caution stops and suspicion takes over 2. The more abnormal a person is on one personality factor, the more likely it is that he will be abnormal on others. In general, however, narcissistic people don’t show the sustained, poisonous hatred of the true paranoid, or the icy, calculated vengefulness seen in psychopathic personalities. Narcissists are too easily distracted to maintain a vendetta; the show must go on. They forget it, brush it off until, months or years later, something happens and it all comes back, as fresh as if it were yesterday.

Many narcissistic people radiate an air of superiority or grandiosity, the sense that they firmly believe they are better than everybody else. This often takes the form of spiteful comments, aimed at humiliating people they see as competition, but also just putting people down generally for laughs. Often, they will lead the laughter, which is cruel and deliberately hurtful, then turn it off suddenly and change the subject. Underneath the show, however, life is very different. Almost always, these people have poor or fragile self-esteem; their surface behaviour is designed to lead people away from this truth. When things go wrong, such as losing a job, a car accident, or being arrested, they crumple into pathetic caricatures of themselves. The exceptions are people who are born to wealth and privilege, who firmly believe they deserve and are entitled to worshipful attention and who exclude from the entourage anybody who doesn’t show a suitably servile attitude. If their favourite project goes wrong or they are arrested for something, they fly into towering rages and threaten eternal retribution for everybody who has let them down. The narcissist is never wrong.

Narcissistic people believe that ordinary rules don’t apply to them. Everything exists for them but, if it doesn’t, it’s too boring to think about. Their emotions are shallow and showy, often mercurial; they love to meet new people and can be charming and entertaining but they quickly work out whom they should cultivate and forget everybody else’s names. They will say whatever they think people want to hear, especially if it makes them look good, but it’s insincere, a flood of empty words designed to charm people and make them feel good. As every narcissist learns very early, happy people are more likely to give you what you want. Confidence tricksters often show strongly narcissistic behaviour. They like to appear clever, witty, sophisticated and experienced when, very often, they are not. Sexually, they like to play seduction games but their sexual identity is often poorly formed and they rarely have the experience they claim, although they manage to blame the partner before moving on.

This is more or less the stereotype of the narcissistic personality but we should mention a couple of variants. People now use the expression “malignant narcissism.” Here, the emphasis is on the individual’s cruel or destructive behaviour so it is more or less synonymous with the older term “creative psychopath.” The central features of the psychopathic syndrome were remorselessness, failure to learn from experience, failure to form caring relationships, and dishonesty. There were three types. The aggressive psychopath was exactly what you would expect, unpredictably violent, destructive, cruel, callous, dishonest, and contemptuous of others’ feelings and of society and its laws. If he wanted something, he got it and anybody who got in the way was smashed down. He moved from one violent relationship to another, leaving a trail of damaged partners and children for others to tend. The inadequate psychopath was similar but tended to drink heavily or use a lot of drugs, and constantly got into trouble for petty dishonesty, unpaid bills, drunken fights he started but quickly lost, and other stupid things. Aggressive when he thought he could win, he quickly dissolved into snivelling and weeping when anybody called him out. He was well-known to the police, who knew they could lean on him for information when they wanted it but he was too unreliable to be a successful criminal. He tended to be more dependent on partners and more manipulative but also more likely to try to suicide when they got sick of his nonsense and kicked him out.

The third flavour was called the creative psychopath. These men (the stereotypes were all male, but there are many psychopathic women as well), these men were charming, urbane, considerate and seductive in equal measure but there was always a goal, an ulterior motive. Again, the central feature was their utter lack of empathy for other humans. Quite often, they would openly say that they saw people as objects to be manipulated and won over, then discarded when they were no longer useful. Generally, they were quite tall, good looking and looked after themselves. Not for them the drugs and alcohol and all night parties; they were on a mission and nothing would stop them. If you would like examples, read the story of the New York financier, Bernard Madoff, but remember: regardless of what anybody said of him after his arrest, Madoff didn’t suddenly become a psychopath just because he was caught. He was one all along, right from his teenage years, because that’s what personality means. However, even if anybody suspected him (the forensic accountant and fraud investigator, Harry Markopoulos, certainly did but nobody believed him because Madoff was rich and good-looking and well-connected), even if anybody had thought he was a psychopath, nobody would have dared breathe it because you couldn’t say that sort of thing about that sort of man. This was also true of the arch-manipulator, Jeffrey Epstein, who had managed to wriggle out of a criminal conviction that should have sunk him. However, because there were so many rich, good-looking and well-connected men who stole, cheated and lied, the diagnosis became an embarrassment to psychiatry and it had to go.

Years ago, when the American Psychiatric Association was revising its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), somebody realised that if they applied the diagnostic criteria for creative psychopath fairly, then it was clear that it applied to a large proportion of the American political, financial, industrial, military, academic, sporting, religious, entertainment, and any other establishment you care to mention. And not just American, it was equally true of all other countries as well. So they did the only honourable thing open to them, they changed the name and rejigged the criteria so that the wealthy would never meet them – well, until they went to prison, which wealthy law-breakers almost never do. The term “psychopath” was dropped and replaced by “sociopath’ (now known as “antisocial personality disorder”) of which the essential feature is constant law-breaking due to physical and sexual aggression. High-flying businessmen and politicians could avoid the label although, as Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell showed, only because the rich can conceal their crimes whereas the poor can’t.

As for examples, who do you want? Maxwell’s father, Robert? A classic creative psychopath, friend of the uber-wealthy and over-powerful. What about the chairman of Lehman Bros, the Wall St investment bank that collapsed in 2008, who, because of his aggressive and ultimately destructive behaviour, was known as “the gorilla of Wall St”? That was not a title freely handed out: he earned it against some very stiff competition but he wasn’t a sociopath because he has never been convicted. More recently, the Silicon Valley venture capitalist, Peter Thiel, was quoted as saying “I’d rather be seen as evil than incompetent” [3]. Needless to say, I’ve never met Mr Thiel so I don’t know anything about his personality but, whether he said it or not and regardless of context, that statement is the very essence of narcissism and psychopathy. It is narcissistic in that it implies the person’s image is more important than anything else, including morality, and it is psychopathic in that it licences evil. If everybody followed that principle, the world would descend into anarchy. Or further than it already has.

In short, the concept of malignant narcissism is more or less the same as the creative psychopath. It would be a brave psychiatrist who would call a powerful politician or the son of a fabulously wealthy businessman a psychopath. So they get the fashionable but artfully misleading diagnosis of “malignant narcissism” that gets them off the hook for their various escapades.

Now just as there were “inadequate psychopaths,” however we define those terms, it is the case that there are plenty of people who will meet the criteria for narcissistic personality disorder who also warrant the unflattering label “inadequate.” In fact, we’re not supposed to use terms like “inadequate” these days, on the basis that they are demeaning and pejorative. That’s fine, but it is still the case that many people with strongly narcissistic traits are also fearful, miserable, irritable, withdrawn, prickly, defensive, unreliable, inclined to gamble, drink or use drugs, and are promiscuous and dishonest. That is, they are inadequate to the social demands of functioning as independent adults. My view is that a careful psychiatric history and examination will show that most of them are seriously anxious [4], their lives complicated by secondary depression, but they tend to conceal this. At the same time, most psychiatrists, who don’t take anxiety seriously, don’t enquire too hard. As soon as they find the criteria for personality disorder, they either push the patient out the door or, if he can afford to come back, adroitly relabel him as bipolar, ADHD, ASD, ODD, substance abuse, major depression and so on, and put him on drugs.

The final point to make is to answer the very obvious question: Why would anybody bother with the drama? Who cares whether she is the centre of attention? Who cares who is president of the local fishing club, why would anybody waste money on having the biggest car, newest outfit, flashiest hair style and so on? The answer is clear: people with no inner sense of self-worth who have to generate a sense of worth on the outside. They are hoping to fool others and, in the process, to fool themselves but, inside, things are never as good as they make out. Mostly, they are unhappy with everything about themselves and their lives; the concept of “Be satisfied with what you’ve got, it could always be worse,” as your old granny told you, bounces off them. They’re never satisfied with what they’ve got because they’re not satisfied with who they are. At base, narcissism is a self-esteem issue. They try to construct an illusion of self-assurance but it’s brittle and easily shatters.

That, as Freud pointed out, goes back to childhood but, as a general rule, people who show a desperate need to be at the centre of attention, to be in control at all times, either have very little sense of self-worth or, rarely, a bloated sense of self-worth as in the pampered offspring of absolute monarchs or the obscenely wealthy. People who inherit power and money believe they should be the centre of attention because they deserve it, they want people to believe they’re wonderful because they firmly believe that, by birth, they are indeed wonderful and everybody should bow down as they pass or risk losing their heads. But we won’t be talking about them as the problems of the wealthy are rather small (as distinct from the problems they cause the rest of us).

1.3: Narcissism is as narcissism does.

What does all this mean in practice? People don’t walk around with a scarlet N stitched to their sleeves, so how is the ordinary citizen to recognise “one of them”? Is there any need to? To a large extent, that depends on what you want. If you’re a talent scout looking for extras in a TV show, you will want somebody who, as they say, “projects” herself. You don’t want a shy, self-effacing little thing who hangs around at the back of the crowd and bursts into nervous giggling when anybody tries to talk to her. Your director wants somebody who can make an impression, who stands out boldly, somebody a bit larger than life whose very presence demands “Look at me, everybody.” This is the hallmark of the narcissist, the sense that this person lives on a stage, that she is supremely aware of all eyes being on her, drinking her in, which, in turn, she drinks in. Yes, you can almost hear her saying to herself, this I like, their attention is better than any drug, their applause is so exciting, better even than sex, so give it to me, give it to me. The clothes, the hair, teeth, makeup and jewellery, the cars and travel and restaurants are all part of the endless act called life. After all, who would look at a narcissist in cast-off clothes waiting in the rain for the bus?

And she gives it back. Her laughter makes the day brighter, even her smiles seem loud; the room feels busier and more exciting when she comes in and rather flat when, with but a single, breathy goodbye, she takes heartfelt, individual leave of every person in the room – or so it feels. And that’s important: she charms everybody. She radiates a buoyant confidence and security that make people feel they are important to her, that her approval counts, that they want to be in her life even if only by cleaning up after the party. Who does she charm? Certainly not other narcissists, as the history of catfights among film stars shows (of Tallulah Bankhead’s passing, Bette Davis said: “It’s bad to speak ill of the dead. She’s dead. Good”). No, they charm their polar opposites: the sad and lonely, the insecure and easily intimidated, the vague and uncertain, but also the stern and humourless and, above all, the powerful, wealthy and influential, meaning about 50% of the population in total. The closer unhappy people are to one of nature’s inspiringly bright souls, the better they feel and the more they want to do to help. Of course, there will always be the odd curmudgeon who can’t abide her but criticism of the sainted one provokes her followers to immediate and fierce defence. Thus we chance upon a peculiar dyad: while the narcissist demands undying devotion, her loyal followers are eager, even desperate, to give it just because being part of her entourage makes their drab lives better. But devotion is nothing more than iron control dressed in a velvet glove. Have we heard this before? We have, many times, and we’ll return to it.

One of the defining features of narcissism is that they are attracted to power and wealth. Wherever the spotlight is, that’s where they want to be. Most narcissists, however, are not so lucky; while washing the dishes, they may dream of bestriding Tinseltown but most will need to be satisfied with dominating the office or workshop, the school play, the church or sports club committee or local political branch meetings. That’s the fun side of suburban narcissism but if that’s all they did, nobody would bother writing books about them. A happy narcissist who is getting the attention he feels he deserves can be entertaining but, when things go wrong and he’s unhappy or angry, it’s a different story. Suddenly, the glamorous mask comes off and the suspicious and resentful bits show through. He becomes irritable and demanding; nothing is good enough; people are letting him down; he can’t rely on anybody; nobody cares; people are all the same; nobody understands; nobody wants to listen; don’t they realise he’s a person with feelings? But even the tantrums are scripted for an audience: not for him the grim withdrawal and silent self-denial. Even the sulking bouts are theatrically dramatic. Always there is that impression that he is watching himself perform, scanning his every effusive word. Even in the sulks, his dramatic gestures are planned to a T, his entrances are grand, his compliments over the top, hair and clothes too elaborate, his laughter a bit too loud, his hints are actually demands, on and on. But to see the real person, all you need to do is look away while he’s talking, or compliment somebody else, or change the subject, and then the drama starts.

The trouble for the audience caught up in a tantrum is that nobody ever really knows what’s gone wrong or, if they have worked it out, it seems blown out of all proportion. However, everybody knows better than to say so, it can turn a minor storm in a teacup into world war three. And so he controls people, moves them around like pawns on a board or supporting actors in a huge drama in which he is prima donna assoluta. The true narcissist uses people as props in his lifelong drama. If he wants something, including a person, he drops everything and goes for it. When he gets whatever it is, it must play its role in his never-ending soap. If he can’t get it, he throws a tantrum then declares he didn’t want it anyway. Typically for female narcissists, children have to play the roles mummy decides for them. One will be a famous dancer or actor, one has already decided to be a doctor “Haven’t you, darling,” one has the makings of a poet, and heaven help them if they don’t slot into their appointed roles. They will be dragged off to a psychiatrist who, under the deluge of troubles recounted by the mother, will have little choice but to declare the child does indeed have the diagnosis mother has decided and needs to be put on drugs. Then she is able to play the role of the long-suffering mother, which has endless subthemes and never runs out.

The narcissistic personality disorder is disordered personality first and egotist second. The trait of self-centredness is universal; all that differs is the degree. The only problem with all that has been said so far is that most people assume narcissists are either women or effeminate. In one of the most remarkable feats of manipulating public sentiment in humanity’s long and dispiriting history, heterosexual men have managed to convince the world that narcissism afflicts only women and gays. Look at all the money they spend on clothes, the real men say; look at their jewellery, their cosmetics, hair, nails, and all the time they spend in front of mirrors, primping and preening to “look their best.” Women can’t walk past a mirror without checking to see their seams are straight, their hair fluffed, their tattoos showing to their best… Men, as they will eagerly tell you, are far too rational and sensible to fall for nonsense such as self-involvement, self-interest and all that. Men they just get on with the job and do it without a fuss, with no drama and no shrieks of “But what will people think of me?” Men don’t care what people think, they decide what to wear by checking the weather forecast; they have their hair cut according to the calendar; they change their socks only when necessary; and they don’t lose sleep over a few holes in the undies. Men are sensible, grounded, pragmatic… or so their story goes.

This, of course, is utter rubbish but the amazing part of this inestimable duplicity is that men actually believe it too. The example par excellence is, of course, one Donald J Trump, sometime president of the USA. Some psychiatrists are on record as saying Trump was delusional, a paranoid psychotic, but that’s incorrect. He showed all the features of a personality disorder; his claims that he was the greatest, or his crowds were the biggest, or he won in 2020, were not delusional as he didn’t believe them. He said them just for effect and he knew that if he kept repeating a bit of self-serving nonsense, eventually everyone would believe it and he could go from there. But he never believed anything he said.3 He wasn’t interested in the job, he just resented being treated as a bit of New York low-life outsider by the insiders, so he showed them. He snatched their golden fleece from under their noses and then didn’t know what to do with it. So he simply carried on in Trumpian manner, wheeling and dealing, scheming, manipulating, threatening people or charming them, wheedling and cajoling but with most of his limited attention fixed firmly on his ratings.

Other people said he was a political genius. No, he wasn’t. He simply had the immeasurable luck to stumble into the public eye at a time when people were increasingly tired of the corruption, contempt and incompetence of the mainstream political, financial, industrial, military, academic, sporting, religious, entertainment, and any other establishment you care to mention. By shouting out that the establishment were corrupt and incompetent which, as an outsider, he believed and which they are, he fooled enough voters into thinking that he would do something about their enemies and that their miserable lives would thereby get better. He didn’t, and they haven’t. He simply fed voters what they wanted to hear, meaning their prejudices, over and over again because their prejudices were also his prejudices and he had nothing else to offer. He had no policies and no plans beyond throwing dirt at his enemies (who happened to be his voters’ enemies) and watching them squirm. He didn’t know anything at all about government and he cared even less. All he wanted was the TV cameras and the satisfaction of sitting at the Big Desk, tossing off insults to the people who despised him while the suits and uniforms stood silently by, in awe of his majesty. That is pure personality disorder.

Others said he was just a crook. Probably, but he was certainly not alone. During his term, Trump is recorded as telling 30,573 lies, in addition to the ten thousand a month since he left office. That is quite a lot, even for a politician, but his were silly little lies, as distinct from the Big Lies that are the stock in trade of the denizens of parliaments the world over. He claimed his inauguration crowd was the biggest when everybody could see it wasn’t. Boris Johnston slithered his way to power by promising that Brexit would deliver the country to sunny uplands. By any estimation, it has been an abject failure and could well result in the country fracturing but nobody is holding him to account because, as they say, he told only one lie.