8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

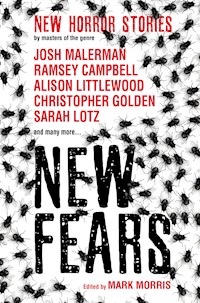

WINNER OF THE 2018 BRITISH FANTASY SOCIETY AWARD FOR BEST ANTHOLOGY. Includes Josh Malerman's 'House of the Head' as seen in Creepshow. An electrifying anthology of new horror stories by award-winning masters of the genre, including Josh Malerman, Ramsey Campbell, Alison Littlewood and Christopher Golden. FEAR COMES IN MANY FORMS The horror genre's greatest living practitioners drag our darkest fears kicking and screaming into the light in this collection of nineteen brand-new stories. In "The Boggle Hole" by Alison Littlewood an ancient folk tale leads to irrevocable loss. In Josh Malerman's "The House of the Head" a dollhouse becomes the focus for an incident both violent and inexplicable. And in "Speaking Still" Ramsey Campbell suggests that beyond death there may be far worse things waiting than we can ever imagine... Numinous, surreal and gut wrenching, New Fears is a vibrant collection showcasing the very best fiction modern horror has to offer.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also Available From Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

INTRODUCTIONby Mark Morris

THE BOGGLE HOLEby Alison Littlewood

SHEPHERDS’ BUSINESSby Stephen Gallagher

NO GOOD DEEDby Angela Slatter

THE FAMILY CARby Brady Golden

FOUR ABSTRACTSby Nina Allan

SHELTERED IN PLACEby Brian Keene

THE FOLD IN THE HEARTby Chaz Brenchley

DEPARTURESby A.K. Benedict

THE SALTER COLLECTIONby Brian Lillie

SPEAKING STILLby Ramsey Campbell

THE EYES ARE WHITE AND QUIETby Carole Johnstone

THE EMBARRASSMENT OF DEAD GRANDMOTHERSby Sarah Lotz

EUMENIDES (THE BENEVOLENT LADIES)by Adam L.G. Nevill

ROUNDABOUTby Muriel Gray

THE HOUSE OF THE HEADby Josh Malerman

SUCCULENTSby Conrad Williams

DOLLIESby Kathryn Ptacek

THE ABDUCTION DOORby Christopher Golden

THE SWAN DIVEby Stephen Laws

Contributors’ Notes

Also Available From Titan Books

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

NEW FEARS

Print edition ISBN: 9781785655524 Electronic edition ISBN: 9781785655586

Published by Titan Books A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd 144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First Titan Books edition: September 2017 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction Copyright © 2017 Mark Morris

The Boggle Hole Copyright © 2017 Alison LittlewoodShepherds’ Business Copyright © 2017 Stephen GallagherNo Good Deed Copyright © 2017 Angela Slatter

The Family Car Copyright © 2017 Brady GoldenFour Abstracts Copyright © 2017 Nina AllanSheltered In Place Copyright © 2017 Brian Keene

The Fold In The Heart Copyright © 2017 Chaz Brenchley

Departures Copyright © 2017 A.K. BenedictThe Salter Collection Copyright © 2017 Brian LillieSpeaking Still Copyright © 2017 Ramsey Campbell

The Eyes Are White and Quiet Copyright © 2017 Carole JohnstoneThe Embarrassment Of Dead Grandmothers Copyright © 2017 Sarah LotzEumenides (The Benevolent Ladies) Copyright © 2017 Adam L.G. Nevill

Roundabout Copyright © 2017 Muriel Gray

The House of the Head Copyright © 2017 Josh Malerman

Succulents Copyright © 2017 Conrad Williams

Dollies Copyright © 2017 Kathryn Ptacek

The Abduction Door Copyright © 2017 Christopher Golden

The Swan Dive Copyright © 2017 Stephen Laws

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

I believe that the first adult horror novel I read was James Herbert’s The Fog back in 1976, when I was twelve or thirteen years old. But I’d been reading horror fiction for several years before then. Like many writers of my generation, I cut my genre teeth not on novels, but short stories—dozens of short stories, hundreds, maybe even thousands.From an early age I’d been a voracious reader—I still am—and in between the Enid Blytons, and Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings series, and Doctor Who novelisations, and children’s classics like 101 Dalmatians, Charlotte’s Web, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Treasure Island, I read anthologies—mostly ghost and horror stories, some of which I owned, but many of which I borrowed from my local library.

Anthologies I remember reading and loving in my preteen years include Nightfrights, edited by Peter Haining, Ghosts, Spooks and Spectres, edited by Charles Molin, Alfred Hitchcock’s Ghostly Gallery and a Target book edited by Freya Littledale called Ghosts and Spirits of Many Lands.

There were anthology series too—fifteen volumes of The Armada Ghost Book, six volumes of The Armada Monster Book, and four volumes of Armada Sci-Fi.

And then, of course, there were the annual Pan and Fontana Books of Horror and Ghost Stories.

My first encounter with one of these august editions was in 1972 when I was nine. The book in question was The 7th Fontana Book of Great Horror Stories edited by Mary Danby, and I was immediately captivated by the yellow-green photographic cover, depicting a rat slinking between glass containers on a laboratory bench. The book was owned by my cousin, and as soon as she showed it to me I knew I had to read it. To be honest, I can’t remember what I made of the stories at the time (though, perusing the contents, I see contributions from such genre luminaries as Gerald Kersh, Robert Bloch, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Marjorie Bowen and M.R. James), but I do vividly recall, a few years later, exactly how I felt after reading my first Pan Book of Horror Stories.

It was New Year’s Eve 1975, and I was staying at a friend’s house. I was sleeping in a camp bed on the ground floor at the front of the house, in some kind of box room or study. As I recall, there was quite a bit of clutter in the room—boxes, clothes hanging up, stacked items of furniture. At bedtime I settled down to read the book I’d brought with me: The Eleventh Pan Book of Horror Stories.

I’m not sure how much of the book I read that night, but I do know it was well into the early hours of 1st January 1976 when I finally turned out the lamp beside my bed and tried to settle down to sleep.

I say tried, because as soon as I closed my eyes I started to imagine I could hear rustling sounds in the darkness; started to believe that some thing had emerged from hiding and was creeping towards my bed.

Worse, opening my eyes to allay my fears only served to exacerbate them. Because in the gloom, with the only light a brownish glow on the closed curtains from the streetlight outside, I saw shapes that seemed to feed my imaginings. There was a tall figure standing by the wardrobe, a hunched mass beneath the windowsill. Snapping on the bedside lamp in rising panic, the tall figure would quickly disguise itself as a hanging item of clothing, the hunched mass a pile of boxes. But then I’d turn the light off, and after a few seconds the rustling would start again…

In my fevered state, the long hours to dawn became a waking nightmare, and I eventually fell into an exhausted sleep only when the sky outside began to lighten and the shadows began to dissipate. Yet, oddly enough, although the experience left me drained, I now look back on it with a sense of nostalgia, even fondness. It showed me how powerful good horror fiction could be, and it certainly didn’t put me off seeking out more of it. On the contrary, over the next few years I devoured as many of the Pan and Fontana anthologies as I could get my hands on. They fuelled my imagination, and instilled in me a long-held belief that short fiction, perhaps even more so than novels, is the lifeblood of the genre.

There’s nothing better than a well-crafted ghost or horror story. Short stories, if told well, can retain a real sense of dread throughout their twenty-or thirty-page length, and pack a real punch. All too often horror novels—perhaps because their authors feel a need to reward readers for the time they’ve invested in their work—end on a note of hope or redemption: the evil vanquished, the status quo restored. In short stories, however, there are no such restrictions, which is why short horror fiction tends to be darker and less reassuring, not to mention generally more ambiguous and experimental, than lengthier, more conventional works.

As a child I loved the fearful anticipation of reading an anthology and not knowing what was coming up next. Would the next story be scary, funny, baffling? Would it be supernatural or non-supernatural? Would it contain witchcraft, a haunting, cannibals, demonic possession? Or would it be something even stranger, darker, altogether more difficult to define?

The recent trend in the genre has been for themed anthologies; collections of stories about a particular subject. We’ve had books of werewolf stories and zombie stories; books featuring stories sharing common characters, or all set within a particular location. Undeniably many of these anthologies have been excellent, their contributors showing a great deal of invention and flair in the way they’ve subverted the restrictions imposed on them, and interpreted the various themes in their own way. Yet whenever I read a themed anthology, I always secretly find myself craving the kinds of anthologies I read in my youth, anthologies in which no restrictions were placed on the authors, and their imaginations were given free rein.

This, then, is where New Fears comes in. In this first volume of what will hopefully become an annual showcase of the best and most varied short fiction that the horror genre has to offer, you’ll find a wide variety of stories and approaches, which will hopefully demonstrate how very wide—indeed, how almost limitless—the parameters of the genre can be. Within these pages you’ll find stories that explore ancient myths in new and innovative ways; stories of human evil; stories of unnamed and ambiguous terrors; stories where the numinous and the inexplicable intrude upon what we perceive to be reality in unexpected ways. There is humour here, and hope, and grief, and sadness, and regret, and impenetrable darkness. There are stories that will surprise you, and unsettle you, and shock you. But most of all there are stories that will grab you and draw you in and compel you to keep turning the pages.

There is so much that this amazing genre of ours has to offer.

New Fears 1 is only the start of the journey.

MARK MORRIS

February 2017

THE BOGGLE HOLE

by Alison Littlewood

Tim’s grandad’s house wasn’t like a house should be. There were white lacy things on the chair arms, and the wallpaper had knobbly bits in it, and the television was too small and bulged out at the back. The carpet had a texture to it too, pale green ridges Tim could feel through his socks, and the worst thing, the thing he really didn’t like, was the silence that hung over it. It was like it lived there, that silence, like a creature that had moved in and swelled to occupy the space. Tim didn’t know how to banish it. He could only make it retreat, one leg at a time, into some corner or other; but he always knew the effect was temporary, that once he’d finished his game it would stealthily creep back, a bulbous, insidious thing that watched him always, waiting for its chance to pounce.

Tim’s house didn’t have a Silence in it. Now it didn’t have Tim in it either, or his mum; she’d gone on holidays of her own, off to a golden beach with a man Tim scarcely knew. It wasn’t even summer. It was late autumn, all the fallen leaves already lying soggy in the gutters. He scowled when he thought of her, miles and miles away and having fun.

“Penny for ’em, lad,” his grandad said, and Tim realised he’d come into the room behind him, padding on silent slippered feet. Grandad’s slippers were made of brown checked fabric and had holes in the toes. They were so ugly Tim wondered how he had ever come to buy them, but then old people were like that; they didn’t seem to care what anything looked like. He scowled again.

“She’ll be back soon enough, lad,” Grandad said, and he glanced at the window, where the rain had begun to fall in a steady splutter. Tim couldn’t hear it but he could see it spitting against the glass.

“I know you’d rather be in that there Bahaymas.”

Bahamas, thought Tim, but he couldn’t be bothered to correct him.

“’Appen I’ll tek you to a beach,” his grandad said. “You’ll see, it’s not ser bad. There’s nowt on them furren beaches, son. Just wait—ours has got treasures.”

Tim looked up.

“There’s fossils, an—”

Tim sighed.

“Aye, well. You’d rather them Bahaymas. Fair do’s, son.” Grandad sighed and pulled open a drawer in the sideboard. He took out his pipe, hiding the curve of it in his hand. “I’ll just pop for a puff, lad. She dun’t like it in t’ouse, you know.”

Tim frowned as he watched Grandad shuffle towards the door in his slippers. He knew he wouldn’t bother changing into shoes to go outside. He always went in his slippers and he always talked about Grandma when he did it, and Tim didn’t know why; his gran had died years ago, before Tim could even form the memories to remember her by, and yet Grandad still tiptoed around her. She wouldn’t like this. She wouldn’t like that. He would whisper, as if she was there and listening and disapproving. Tim had a picture of a stolid woman with her arms folded across her chest; it didn’t tally with the photograph of a slender, dark-haired girl with laughter in her smile, which sat in an ornate frame on the mantelpiece.

He looked out of the window to see Grandad settling into his usual seat on the rain-damp bench at the end of the garden, puffing on his pipe. The thumb of his left hand kept turning and turning the wedding ring on his finger, over and over, while he stared into the smoke.

* * *

Boggle Hole didn’t look like much of a beach. It lay at the bottom of a narrow gully, a small cove of exposed rock with a stream running through it. The cliffs stretched away; they were the colour of pale sand. The beach was not the colour of sand. Mostly it was black, streaked with the bright-green slime of seaweed.

“What d’you think?” asked Grandad.

Tim tried not to scowl. Boggle Hole, he thought. South of Robin Hood’s Bay. Near Ravenscar. Such a thrill he had felt at the sound of the words, and now the reality was grey and bare and boring. He remembered when Grandad first told him about it. Boggle Oyle, he’d said. We’ll go to Boggle Oyle, and Tim had thought Oil, and wondered why they should want to go to an oily beach; the image in his head had been something he’d seen on television, blackened seabirds being dunked in washing-up bowls by solemn volunteers. Now he looked out at the dark beach under a dark sky and wondered how far off the mark he had been.

“Aye, well. There’s a beach in summer. You can make sandcastles. It gets scoured off, though. Winter’s on its way.” Grandad sniffed the air, as if he could smell it coming.

Tim sniffed too, and got only cold briny sharpness. He wondered if that’s what winter smelled like. He wondered too what kind of beach was only there for some of the time; that did have a whiff of the magical about it, as though it might appear when he turned his back.

“There were smugglers used this beach,” Grandad said. When Tim looked up at him he winked, his face creasing in a hundred places. “Smugglers and maybe wreckers, too. And then there’s the boggle.”

“The boggle?” Tim had thought it was just a name, a strange one, like lots of other names around here. He hadn’t known it was a thing.

Grandad’s eyes brightened. “Come on, lad,” he said. “I’ll show you.”

* * *

The cave was a dark focal point, which the cliff swept towards as if pointing the way. As Tim skipped ahead he found there was some sand on the beach after all; clumps of it clung to his trainers like mud, sticking strands of weed to the white leather. It occurred to him there was noise here too, not like in the house: gulls sounding like scrapping cats; the gritting of his feet; the distant growl of a car on the clifftop. Beneath it all the sea was shushing, as if telling everything else to shut up and listen.

Inside the cave, though, it was quiet. He could still hear the sea but it was as if the cave had its own Silence inside it, a presence that was trying to keep the noise out. Then Grandad huffed and puffed his way inside, and the thought was gone.

“This is it, lad.”

Tim turned. “What?” He’d forgotten about the boggle, but he remembered when he saw the wink, the fissures in the old man’s face.

“The boggle hole. This is it.” Grandad waved his hand around the pocked grey walls. “This is where it lives.”

“What’s a boggle?”

Grandad put his fingers to his lips. “All right, I’ll tell thee. But quiet, like. They don’t like being talked about.” He glanced around as he whispered, “A boggle is a sort of goblin. Some call ’em brownies, or hobs. This one ’ere’s a boggle. Along t’ coast there’s another bay called Hob Hole. That one—well, some used to take their kids there when they got t’ whooping cough. They’d ask the hob to cure ’em, and sometimes it did. It’s true, lad.” Grandad winked again.

Tim hadn’t heard of the whooping cough, didn’t know what it was. He shook his head.

“They say this ’ere boggle started out in Robin Hood’s Bay. But they play tricks, see, and this one played a trick so nasty they banished him. So now he lives here.”

Tim cast his eyes around the cave. It wasn’t a big cave. There didn’t seem to be anywhere a boggle could hide. He looked quizzically at his grandad.

“Oh, you can’t see him. Not unless he wants to be seen.” There was laughter in Grandad’s voice; Tim was no longer sure if it was a real story or something he’d just made up. “Unless…” Grandad raised one shaggy white eyebrow. “They say, if you look in something shiny, you can see t’ boggle’s face. Here.” He slowly worked the wedding ring from his finger and passed it to Tim. “Careful, now. Try that.” He opened his eyes wide as if in fear.

The ring was old and heavy in Tim’s hand. When he looked closely he could see there were layers of fine scratches in it, but between the blemishes, it still shone. He peered at the surface, then quickly looked at the old man, to see if he was being mocked.

Then, in the surface of the ring, he saw a dark outline against a bright oval. It looked a little like a face. He leaned closer and the shape grew bigger; it was nothing but his own reflection. He frowned.

“Aye, well. Maybe he din’t want to come out today. Let’s go and look for fossils. We might find some by t’ beck.”

The sea was loud again in Tim’s ears as he walked by Grandad’s side, talking now of boggles, now of smugglers and now of dinosaurs. The coast was Jurassic, Grandad said, and that made Tim think of T-rexes; he wondered if one could be buried, now, in the cliff. He looked at the beach with different eyes. When he knew the stories, the place was better. Boggle Oyle. He remembered what Grandad had said about his beach: ours has got treasures. He slipped his hand into Grandad’s dry fingers, and when Grandad smiled at him, Tim grinned back.

* * *

The “treasure” was a small grey handful of stone, curled into a tight circle that was roughened at one side where the spiral had broken. It didn’t look like treasure, but Grandad said it was a “hammonite”, so Tim supposed it must be. He examined it while Grandad took out his pipe and lit it, sitting on a large smooth rock at the head of the cove.

After a while Tim stopped looking at the fossil and started watching the sea, and after that he watched Grandad.

“Why don’t you smoke in the house?” he asked, and then caught himself. Now that Grandma isn’t there any more, he had been about to add, but it struck him that it would be cruel, not a nice thing to bring up. When he looked at Grandad, though, he saw the old man knew what Tim had been about to say.

“She never did like it, son,” he said, taking the pipe from his lips and staring down at the damp black stem. “She didn’t like the smell, see. Said it lingered.” His eyes went out of focus. “And she were right, as usual. Bad habit. So I always went outside.”

“But—”

“Aye, I know.” Grandad’s voice was gentle. “I know she’s gone, lad. I could smoke in t’ house if I wanted. But—I sorter think her memory might not like it either, know what I mean? And I don’t want to do something her memory wouldn’t like. Case I chase it away.”

He fell silent, staring into space, and Tim thought he should say something else, but he couldn’t think what. And so he fell silent too, as if it were something catching, like whooping cough maybe. As if it had followed them from the house and onto the beach.

“Come on,” said Grandad, tapping out the burnt contents of his pipe. “We’d best get on. Light’s going already, and the tide comes all t’ way up this beach. You can get stuck. Best put that fossil back, now.”

“Put it back?”

“Aye, lad.” Grandad’s face broke into its steady slow smile. “You mustn’t take anything from this ’ere beach. Din’t I tell you that? It’ll upset t’ boggle, see. Take summat of his and he might just take summat from you. And how’d you like that?” He winked. “’S no lie, lad. Every word of it’s God’s honest truth.”

* * *

They went back to the beach the next day. Tim walked up and down the seafront, peering into rock pools. Some had brownish-pink squashy things clinging to the rock, bulging and flexing as clear water washed over them. The rocks were made rougher still by barnacles, some with smaller barnacles clinging to their sides. Tim tried to grip one and pull it from the rock, but it wouldn’t budge. He stomped instead on a thick mat of bladderwrack, trying to pop the blisters in its dark green fronds.

He looked back up the beach. By the beck—Stoupe Beck, Grandad had called it—two men were standing by the base of the cliff. One of them bent and slipped something into his pocket. Tim grinned. The man had found a fossil— maybe even the same one Tim had found yesterday—and that made him think of the boggle; the revenge it might take for stealing from its beach.

He turned towards Grandad. The old man wasn’t smoking his pipe; he was watching Tim. He grinned and waved and Tim ran towards him, laughing. He put out his hands to catch him when Tim drew close.

“Let’s have a look for the boggle, Grandad.” Tim pointed towards his left hand.

After a moment, the old man understood. He fumbled the ring from his finger and passed it to Tim. “Careful, now.”

Tim wasn’t sure if he meant about the ring or in case he saw the boggle reflected in its surface. He peered into the gold, turning it in his fingers. He could see clouds, and the hazy shape that was him. Nothing else. He frowned. God’shonest truth, the old man had said.

Grandad tapped the side of his nose before holding out his hand for the ring. “Only when he wants to be seen, son,” he said. “Now, how’s about I teach you to find something shiny for yourself?”

They walked up and down the beach, but it didn’t work. Grandad stopped and bent with a “pfft” and scraped through the stones with his fingers. There was nothing.

“You have to walk with the sun behind you, see,” he said. He pointed at their shadows, dim and hazy. Tim turned and tried to make out the sun; there was only a place where the clouds were a little brighter.

“It’s best at sunrise or sunset. You walk with it behind you and it shines ’em up, see, like they’re polished. Sometimes there’s agate, or carnelian. You can’t see ’em for looking, normally. They’re dull, like pebbles. But when the sun’s low and shining on ’em—they glow. You can see t’ gemstones then. They shine right back at you.” He winked. “Maybe it’s the boggle. They’re his treasure too, see. P’raps he won’t let ’em go, not today.”

Tim lit up. “Tomorrow, then?” He looked once more over his shoulder at the faint trembling light.

Grandad sighed, then smiled. “Aye, lad. Tomorrer.”

* * *

The next day, Tim fidgeted through games and sandwiches and television programmes. Sometimes Grandad caught him looking at the window, watching anxiously for rain, and each time he did they would share a smile; sometimes, they laughed. It wasn’t until later, when they were about to set off, that Tim realised he hadn’t thought about the Silence at all. It had retreated, hiding at the back of the airing cupboard or under a bed, somewhere quiet and small and still, until it could come out again. Maybe tomorrer, Tim thought, and grinned to himself as they got into the car.

The sun was bright and low, shining straight into Tim’s eyes, dazzling him. It was going to work. He knew it even as they pulled into the little car park above the beach and saw the fossil hunters packing up to leave. Their car was grey and looked older even than Grandad’s, and when Grandad saw it, he gave a low whistle. “Look at that,” he said in a low voice. “’Appen t’ boggle’s nicked their hubcaps.”

Tim grinned even wider. Take summat of his, he thought, and he might just take summat from you.

At first, Grandad watched while Tim carefully set the sun at his back and walked along the seafront, crunch, crunch over the pebbles. He said he was keeping an eye on the tide just in case, but Tim knew he was really having a puff on his pipe.

When he’d walked a distance away he turned and walked back and then he tried again. This time, the sun seemed— not brighter, but redder. Readier, he thought, and he turned towards the boggle’s cave and stuck out his tongue.

His shadow was sharper where it lay against the pebbles, each stone sharply delineated with a black crescent. Every fissure and crease in the sand had its own crisp shadow. Now, Tim thought. He stretched out one foot in a long stride and let it fall again. Crunch. Then again. Crunch. The sun was at his back. His shadow was long before him. It looked like some kind of giant: for scaring boggles away, he thought. So he can’t hide his treasures. And something shone amid the grey and the murk and the stone. It glowed like living sunset fallen to the beach, a footprint marking the way to the boggle’s hoard.

Tim pounced on it. When he straightened and looked at what was in his hand, though, he frowned. It was nothing but a dull pebble about half the size of his thumb, reddish perhaps, but with a surface that was greyed like old skin. It wasn’t even a nice pebble, and he drew his hand back ready to throw it into the sea when he had a thought.

He turned and the sun glared into his eyes. He held the stone between thumb and finger, and the light shone through it. It was like something alive, the bright orange-red of carnelian. He turned to his grandad with a look of triumph, but the old man was busy tamping out his pipe on a rock. Then he stood and raised a hand, half waving, half beckoning.

Tim looked down at his feet as clear frothing water rushed over them, stirring the tiny stones as if in offering: take one of them instead. He closed his hand over the gemstone and slipped it into his pocket. Then he started to make his way back up the beach.

It was in the car that Grandad made the sound. It was a little choking cough, way back in his throat. Then he started breathing really loud and patting at his coat, wriggling in his seat to check his trouser pockets.

“What’s up, Grandad?” asked Tim.

Grandad didn’t answer; he only looked back at the boy with wide open eyes. They were watery at the edges.

“Grandad?”

“It’s me ring,” he answered at last, and he held out his left hand, the fingers spread. “Me ring, see. Her ring.” He panted and patted some more. “I must ’ave dropped it.” He stopped, gripping the steering wheel as if holding on. “I must ’ave.” He looked down at his hand, at his broad fingers. Tim remembered the way he’d worked the ring off his finger, twisting and pulling until it came loose.

“You looked in it, din’t you, lad?” He turned to Tim, his eyes lighting up. “You did.”

Tim shook his head. “That was yesterday,” he whispered. “Yesterday, Grandad, remember?”

But Grandad hardly seemed to hear as he turned away from Tim, staring out of the window. “It’s too late,” he said, breathless. “Tide’s coming in. It’s too late to go and look.”

* * *

That evening, the Silence was back. It had grown while they were away, stretching itself into corners and around walls and seeping through doorways that should have kept it out. The television was on, but there wasn’t any sound. Grandad stared at it without seeming to see. His eyes hadn’t dried. He kept nodding to himself, as if listening to something Tim couldn’t hear. He kept turning towards the photograph of a grandmother Tim didn’t remember, a woman he didn’t know. He’d glance at it and then away, quickly, as if he couldn’t bear to look any longer.

Tim hunched himself into the chair, trying to make himself smaller. Silence expanded to fill the gap he left behind.

His hand went to his pocket and he found the thing he’d put there. The stone was small and smooth and cold. Tim ran his fingers over it, but it didn’t seem to get any warmer. He turned and turned it in his pocket, and he tried not to think, and he closed his eyes.

* * *

The next day Grandad didn’t talk about the beach. He didn’t seem to want to talk about anything. He made breakfast, his hands shaking, and then he switched on the television and sat there without looking at it.

Tim went to his side. “We’ll find it today, Grandad, won’t we?”

Grandad shifted, but he didn’t reply.

“We’ll go back to the beach, won’t we?”

The old man shot him a quick look and put out a hand and ruffled Tim’s hair. It pulled, but Tim didn’t protest. He was thinking of the stone in his pocket. Me, he was thinking. You should have taken something from me. It wasn’t right. It wasn’t fair.

“Please, Grandad,” he said, and this time his voice got through.

Grandad turned. “I s’pose. Aye, all right then.” Tim had to lean closer to hear him. “Come on, lad.”

A short time later they got out of the car and walked together down the narrow lane, towards the sea. The sky was packed with low gathered clouds and the sea gave back the grey in a dull shine. The waves were slow and effortless, giving way to the beach in tired little wafts.

Grandad stood where he’d sat the day before, looking at the ground. He gestured to Tim. “Go and play now, lad.”

Tim nodded and turned away. He knew where he was going; it was all right. Better that he should go alone. He made his way up the beach. When he looked back, Grandad wasn’t watching. He was staring down at the ground, at the millions of pebbles, and he wasn’t moving.

Tim started to run. He only stopped when he reached the mouth of the boggle hole, listening to the silence coming from inside; and then he stepped forward and went in, and the cave swallowed him.

His hand was in his pocket. He clutched the stone.

He opened his mouth to speak but his voice was hoarse. He cleared his throat. “I brought this for you.” He took the carnelian from his pocket and held it out. “I want you to give the ring back.”

He looked into the corners of the cave. It was no good, it wasn’t here. Instead he felt the Silence massing behind him, coming from the sea. He turned and found he could hear it after all, mocking him: Hush. Hush.

He stepped out into the light and stared. Had the sea taken the ring? It came right up to the cliffs, Grandad had said. Right into the cave. It would have crept over the beach in the dark, greedily sucking and reaching for any bright thing it could find. His gaze went to the roughened rocks between here and the shore, just as the sun cleared the clouds for an instant; it shone back from a watery surface and was gone.

Tim started to walk towards it, picking his way. It was a rock pool, a wide one, its bottom lined with dregs of sand and fringed with black fronds like hair in bathwater. The sides were sharp overhangs; no telling what could be hiding beneath. Crabs, maybe. Fish. Fish with teeth. Tim narrowed his eyes as the light caught the surface of the water once more. Shiny, he thought, and shuddered.

And then he saw what lay beneath the water. He gasped and rushed towards it, falling to his knees onto the rock. It hurt, but he didn’t think about that.

There, lying on the pale sand under the clear water, was a thick gold ring. Tim looked up; his grandad was a small figure standing on the beach, staring into the waves. Maybe it was better that way. Tim could imagine the surprise on his face when he ran to him and held it out. He let out a spurt of air, almost a giggle, and thought he heard an answering sound somewhere behind him.

He tried to turn; there was nothing there. It was an echo, that was all, coming from the cave or the cliff; the sound of water trickling through stone.

When he looked back into the pool, the ring remained. He pushed up one sleeve, gripped a spike of rock and leaned over, pushing his hand into the icy cold. He opened his fingers, grasping for the ring—and they closed on nothing. There was only sand, fine grains of it, the sand he’d wanted to find when he first came here; now he didn’t want it. He let it slip through his fingers with a little cry. He withdrew his hand. When the drips and circles on the water subsided the form took shape again, a golden ring sitting on the surface of the sand. No, not on the surface; above the surface.

Tim frowned and reached for it again, leaning further this time. He poked at the ring with one finger, meaning to spear it through its heart, but there was nothing there.

He sat back again, letting the water grow still. There; a ring, but nothing he could grasp. And then he understood.

“It’s here,” he muttered. “Here. Have it.” He took the carnelian from his pocket and held it over the water a moment, seeing it dull and lifeless in his hand. He let it drop.

The carnelian fell into the water with a plop, and it vanished.

Tim frowned. He leaned in again. There was no carnelian; he couldn’t see it anywhere. He poked at the sand again to see if the stone had been covered in its fall, but there was nothing.

Then he saw a bright glow coming from the other side of the pool; an orange-red glow, something small at the bottom of the water. He shifted his knees, shuffling his way over the rocks. There was something there. He could see it when the sun shone behind him. He glanced at where he’d been. Blinked. He couldn’t understand how it had passed from there to here. Perhaps this water was flowing after all, going back to the sea, and had carried the stone with it. Or maybe it was a reflection, something about the nature of the pool and the sun and his eyes. He shook his head; it didn’t matter. What mattered was, he could see the carnelian below him. It was deeper here. He’d have to lean all the way out, his face nearly touching the water.

He gripped the rocks tightly with one hand and eased himself out over the pool. He plunged in his other arm almost to the shoulder, grasping below him, raking the surface of the sand. There was something cold and hard and smooth under his fingers. He grabbed it and pulled himself back, cold, dripping. When he saw what was in his hand he nearly dropped it. It was an old scratched ring. It was his grandad’s ring.

Tim looked up at the cave mouth and slowly grinned. He gestured with the ring: thank you.

And something caught his eye in the pool as the sun passed overhead: a brief bright shine, and the suggestion of a face, ugly and distorted and fringed with shaggy hair, laughing on the surface of the water. It was there for a moment and then gone. A reflection, he thought, that’s all it was. But he still wasn’t sure as he pushed himself up and started to make his way back over the beach to his grandad, who was motionless, staring at the waves as they broke, over and over, against the shore.

* * *

There was something in Grandad’s eyes. At first they had lit up. It had been just as Tim had imagined, him holding out the ring and the fissures appearing, deep lines of joy written into the old man’s skin. He hadn’t been able to speak. He had only taken the ring and pushed it, trembling, back onto his finger. Then he had opened and closed his hand before wrapping his thin arms around Tim, and they’d looked at each other and they’d laughed.

It was later that the look appeared. A small frown, and a single line between his eyes. It deepened when he looked at Tim. “Where’d you say you found it?” he asked.

Tim pointed up towards the cave. “The boggle had it, Grandad,” he said, and the line grew deeper still.

They walked along the beach some more, but it wasn’t long before they both turned, as if by some unspoken agreement, towards the car.

“We din’t go thee-er,” Grandad muttered as he fumbled the keys from his pocket.

“What, Grandad?”

Pardon, his mother would have said, but his mother wasn’t here.

“We din’t go up near t’ cave yest’day,” said the old man. He didn’t meet Tim’s eyes. He just looked at the keys in his hand. No: at the wedding ring that nestled beneath them. “We din’t go near it.”

“No,” Tim said.

“Did you see owt?”

Tim swallowed. “What?”

“When you looked in t’ ring.”

Tim looked at him, and this time the old man looked back. The thing in his eyes was still there.

Me, Tim thought. You should have taken something from me. Slowly, he shook his head. “I didn’t take it, Grandad. It was the boggle.”

“Aye. Aye, you said.” Grandad heaved a sigh. “Well, it’s back. That’s t’ main thing. Come on then, Tim. Let’s get going, eh.”

Tim, he’d called him, and for the first time it struck him as odd. Grandad never called him Tim. He called him lad, or son; never by his name. It was strange he’d never noticed that before. Now he didn’t know what he was supposed to think about it. But there was nothing to be done but get into the car and start heading towards home as the rain, viciously, began to spit.

* * *

The Silence was there. This time it wasn’t hiding and it wasn’t creeping. It was a fat, sullen thing, sitting in the middle of the room so that Tim could almost see it. He stared at the window, watching the rain streak the glass, time passing outside. Soon his mother would be home. She would come to fetch him, laughing and tanned from her holiday.

Grandad was doing a crossword in the newspaper, his reading glasses perched on the end of his nose and his wedding ring shining on his finger. They hadn’t spoken about it since they came back from the beach. They hadn’t been back there, either. They had been here, in this house, with the Silence sitting between them.

Tim drew a deep breath. “Grandad, about the boggle.” Grandad buried his nose deeper into the paper.

“If the boggle took summat from you, and you took—”

“That’s enough o’ that now.” Grandad let the newspaper drop with a loud rustle. “Enough o’ that.” After a moment his look softened and he gave a small smile.

“But, Grandad—”

“It’s nowt but a story, Tim,” the old man said. After a moment, he raised the newspaper again, holding it close to his eyes.

Nowt but a story.

Tim thought of the thing he’d seen in the surface of the water, its bright cruel grin; a whisper of laughter heard over his shoulder. He closed his eyes tightly. Grandad was surely right: things like that couldn’t be. It was nothing but a story, and Tim had been lucky to find the ring, and that was all.

’S no lie, lad. Every word of it’s God’s honest truth.

He remembered the way they had laughed together. The way they had winked. It had been different then, when there was the story between them. Something that was for them, and them alone.

He thought of the fossil hunters, trolling their way along the base of the cliff. Them returning to their car and finding their hubcaps gone, being tormented perhaps by whispers and nips and things missing from their pockets; things they’d never get back.

He was forgiven; he knew that. But he knew the old man would never forget, no more than he could forget his dead wife’s face when he stared into his pipe smoke. It was there, an intangible writhing thing.

Me, he’d thought. You should have taken something from me.

But as Tim watched the old man intent on the newspaper, that line still there between his eyes, he knew that was exactly what the boggle had done.

SHEPHERDS’ BUSINESS

by Stephen Gallagher

Picture me on an island supply boat, one of the old Clyde Puffers, seeking to deliver me to my new post. This was 1947, just a couple of years after the war, and I was a young doctor relatively new to general practice. Picture also a choppy sea, a deck that rose and fell with every wave, and a cross-current fighting hard to turn us away from the isle. Back on the mainland I’d been advised that a hearty breakfast would be the best preventative for seasickness and now, having loaded up with one, I was doing my best to hang onto it.

I almost succeeded. Perversely, it was the sudden calm of the harbour that did for me. I ran to the side and I fear that I cast rather more than my bread upon the waters. Those on the quay were treated to a rare sight; their new doctor, clinging to the ship’s rail, with seagulls swooping in the wake of the steamer for an unexpected water-borne treat.

The island’s resident constable was waiting for me at the end of the gangplank. A man of around my father’s age, in uniform, chiselled in flint and unsullied by good cheer. He said,“Munro Spence? Doctor Munro Spence?”

“That’s me,” I said.

“Will you take a look at Doctor Laughton before we move him? He didn’t have too good a journey down.”

There was a man to take care of my baggage, so I followed the constable to the harbour master’s house at the end of the quay. It was a stone building, square and solid. Dr Laughton was in the harbour master’s sitting room behind the office. He was in a chair by the fire with his feet on a stool and a rug over his knees and was attended by one of his own nurses, a stocky red-haired girl of twenty or younger.

I began,“Doctor Laughton. I’m…”

“My replacement, I know,” he said. “Let’s get this over with.”

I checked his pulse, felt his glands, listened to his chest, noted the signs of cyanosis. It was hardly necessary; Dr Laughton had already diagnosed himself, and had requested this transfer. He was an old-school Edinburgh-trained medical man, and I could be sure that his condition must be sufficiently serious that “soldiering on” was no longer an option. He might choose to ignore his own aches and troubles up to a point, but as the island’s only doctor he couldn’t leave the community at risk.

When I enquired about chest pain he didn’t answer directly, but his expression told me all.

“I wish you’d agreed to the aeroplane,” I said.

“For my sake or yours?” he said. “You think I’m bad. You should see your colour.” And then, relenting a little, “The airstrip’s for emergencies. What good’s that to me?”

I asked the nurse,“Will you be travelling with him?”

“I will,” she said. “I’ve an aunt I can stay with. I’ll return on the morning boat.”

Two of the men from the Puffer were waiting to carry the doctor to the quay. We moved back so that they could lift him between them, chair and all. As they were getting into position Laughton said to me,“Try not to kill anyone in your first week, or they’ll have me back here the day after.”

I was his locum, his temporary replacement. That was the story. But we both knew that he wouldn’t be returning. His sight of the island from the sea would almost certainly be his last.

Once they’d manoeuvred him through the doorway, the two sailors bore him with ease toward the boat. Some local people had turned out to wish him well on his journey.

As I followed with the nurse beside me, I said, “Pardon me, but what do I call you?”

“I’m Nurse Kirkwood,” she said. “Rosie.”

“I’m Munro,” I said. “Is that an island accent, Rosie?”

“You have a sharp ear, Doctor Spence,” she said.

She supervised the installation of Dr Laughton in the deck cabin, and didn’t hesitate to give the men orders where another of her age and sex might only make suggestions or requests. A born matron, if ever I saw one. The old salts followed her instruction without a murmur.

When they’d done the job to her satisfaction, Laughton said to me, “The latest patient files are on my desk. Your desk, now.”

Nurse Kirkwood said to him, “You’ll be back before they’ve missed you, Doctor,” but he ignored that.

He said,“These are good people. Look after them.”

The crew were already casting off, and they all but pulled the board from under my feet as I stepped ashore. I took a moment to gather myself, and gave a pleasant nod in response to the curious looks of those well-wishers who’d stayed to see the boat leave. The day’s cargo had been unloaded and stacked on the quay and my bags were nowhere to be seen. I went in search of them and found Moodie, driver and handyman to the island hospital, waiting beside a field ambulance that had been decommissioned from the military. He was chatting to another man, who bade good day and moved off as I arrived.

“Will it be much of a drive?” I said as we climbed aboard.

“Ay,” Moodie said.

“Ten minutes? An hour? Half an hour?”

“Ay,” he agreed, making this one of the longest conversations we were ever to have.

* * *

The drive took little more than twenty minutes. This was due to the size of the island and a good concrete road, yet another legacy of the army’s wartime presence. We saw no other vehicle, slowed for nothing other than the occasional indifferent sheep. Wool and weaving, along with some lobster fishing, sustained the peacetime economy here. In wartime it had been different, with the local populace outnumbered by spotters, gunners, and the Royal Engineers. Later came a camp for Italian prisoners of war, whose disused medical block the Highlands and Islands Medical Service took over when the island’s cottage hospital burned down. Before we reached it we passed the airstrip, still usable, but with its gatehouse and control tower abandoned.

The former prisoners’ hospital was a concrete building with a wooden barracks attached. The Italians had laid paths and a garden, but these were now growing wild. Again I left Moodie to deal with my bags, and went looking to introduce myself to the senior sister.

Senior Sister Garson looked me over once and didn’t seem too impressed. But she called me by my title and gave me a briefing on everyone’s duties while leading me around on a tour. It was then that I learned my driver’s name. I met all the staff apart from Mrs Moodie, who served as cook, housekeeper, and island midwife.

“There’s just the one six-bed ward,” Sister Garson told me. “We use that for the men and the officers’ quarters for the women. Two to a room.”

“How many patients at the moment?”

“As of this morning, just one. Old John Petrie. He’s come in to die.”

Harsh though it seemed, she delivered the information in a matter-of-fact manner.

“I’ll see him now,” I said.

Old John Petrie was eighty-five or eighty-seven. The records were unclear. Occupation: shepherd. Next of kin: none—a rarity on the island. He’d led a tough outdoor life, but toughness won’t keep a body going forever. He was now grown so thin and frail that he was in danger of being swallowed up by his bedding. According to Dr Laughton’s notes he’d presented with no specific ailment. One of my teachers might have diagnosed a case of TMB: Too Many Birthdays. He’d been found in his croft house, alone, half-starved, unable to rise. There was life in John Petrie’s eyes as I introduced myself, but little sign of it anywhere else.

We moved on. Mrs Moodie would bring me my evening meals, I was told. Unless she was attending at a birth, in which case I’d be looked after by Rosie Kirkwood’s mother who’d cycle up from town.

My experience in obstetrics had mainly involved being a student and staying out of the midwife’s way. Senior Sister Garson said,“They’re mostly home births with the midwife attending, unless there are complications and then she’ll call you in. But that’s quite rare. You might want to speak to Mrs Tulloch before she goes home. Her baby was stillborn on Sunday.”

“Where do I find her?” I said.

The answer was, in the suite of rooms at the other end of the building. Her door in the women’s wing was closed, with her husband waiting in the corridor.

“She’s dressing,” he explained.

Sister Garson said, “Thomas, this is Doctor Spence. He’s taking over from Doctor Laughton.”

She left us together. Thomas Tulloch was a young man, somewhere around my own age but much hardier. He wore a shabby suit of all-weather tweed that looked as if it had outlasted several owners. His beard was dark, his eyes blue. Women like that kind of thing, I know, but my first thought was of a wall-eyed collie. What can I say? I like dogs.

I asked him,“How’s your wife bearing up?”

“It’s hard for me to tell,” he said. “She hasn’t spoken much.” And then, as soon as Sister Garson was out of earshot, he lowered his voice and said,“What was it?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“The child. Was it a boy or a girl?”

“I’ve no idea.”

“No one will say. Daisy didn’t get to see it. It was just, your baby’s dead, get over it, you’ll have another.”

“Her first?”

He nodded.

I wondered who might have offered such cold comfort. Everyone, I expect. It was the approach at the time. Infant mortality was no longer the commonplace event it once had been, but old attitudes lingered.

I said,“And how do you feel?”

Tulloch shrugged. “It’s nature,” he conceded. “But you’ll get a ewe that won’t leave a dead lamb. Is John Petrie dying now?”

“I can’t say. Why?”

“I’m looking after his flock and his dog. His dog won’t stay put.”

At that point the door opened and Mrs Tulloch—Daisy— stood before us. True to her name, a crushed flower. She was pale, fair, and small of stature, barely up to her husband’s shoulder. She’d have heard our voices, though not, I would hope, our conversation.

I said, “Mrs Tulloch, I’m Doctor Spence. Are you sure you’re well enough to leave us?”

She said, “Yes, thank you, Doctor.” She spoke in little above a whisper. Though a grown and married woman, from a distance you might have taken her for a girl of sixteen.

I looked to Tulloch and said,“How will you get her home?”

“We were told the ambulance?” he said. And then, “Or we could walk down for the mail bus.”

“Let me get Mister Moodie,” I said.

* * *

Moodie seemed to be unaware of any arrangement, and reluctant to comply with it. Though it went against the grain to be firm with a man twice my age, I could see trouble in our future if I wasn’t. I said, “I’m not discharging a woman in her condition to a hike on the heath. To your ambulance, Mister Moodie.”

Garaged alongside the field ambulance I saw a clapped-out Riley Roadster at least a dozen years old. Laughton’s own vehicle, available for my use.

As the Tullochs climbed aboard the ambulance I said to Daisy,“I’ll call by and check on you in a day or two.” And then, to her husband,“I’ll see if I can get an answer to your question.”

My predecessor’s files awaited me in the office. Those covering his patients from the last six months had been left out on the desk, and were but the tip of the iceberg; in time I’d need to become familiar with the histories of everyone on the island, some fifteen hundred souls. It was a big responsibility for one medic, but civilian doctors were in short supply. Though the fighting was over and the forces demobbed, medical officers were among the last to be released.

I dived in. The last winter had been particularly severe, with a number of pneumonia deaths and broken limbs from ice falls. I read of frostbitten fishermen and a three-year-old boy deaf after measles. Two cases had been sent to the mainland for surgery and one emergency appendectomy had been performed, successfully and right here in the hospital’s theatre, by Laughton himself.

Clearly I had a lot to live up to.

Since October there had been close to a dozen births on the island. A fertile community, and dependent upon it. Most of the children were thriving, one family had moved away. A Mrs Flett had popped out her seventh, with no complications. But then there was Daisy Tulloch.

I looked at her case notes. They were only days old, and incomplete. Laughton had written them up in a shaky hand and I found myself wondering whether, in some way, his condition might have been a factor in the outcome. Not by any direct failing of his own, but Daisy had been thirty-six hours in labour before he was called in. Had the midwife delayed calling him for longer than she should? By the time of his intervention it was a matter of no detectable heartbeat and a forceps delivery.

I’d lost track of the time, so when Mrs Moodie appeared with a tray I was taken by surprise.

“Don’t get up, Doctor,” she said. “I brought your tea.”

I turned the notes face down on the desk and pushed my chair back. Enough, I reckoned, for one day.

I said,“The stillbirth, the Tullochs. Was it a boy or a girl?”

“Doctor Laughton dealt with it,” Mrs Moodie said. “I wasn’t there to see. It hardly matters now, does it?”

“Stillbirths have to be registered,” I said.

“If you say so, Doctor.”

“It’s the law, Mrs Moodie. What happened to the remains?”

“They’re in the shelter for the undertaker. It’s the coldest place we have. He’ll collect them when there’s next a funeral.”

I finished my meal and, leaving the tray for Mrs Moodie to clear, went out to the shelter. It wasn’t just a matter of the Tullochs’ curiosity. With no note of gender, I couldn’t complete the necessary registration. Back then, the bodies of the stillborn were often buried with any unrelated female adult. I had to act before the undertaker came to call.

The shelter was an air-raid bunker located between the hospital and the airfield, now used for storage. And when I say storage, I mean everything from our soap and toilet roll supply to the recently deceased. It was a series of chambers mostly buried under a low, grassy mound. The only visible features above ground were a roof vent and a brick-lined ramp leading down to a door at one end. The door had a mighty lock, for which there was no key.

Inside, I had to navigate my way through rooms filled with crates and boxes to find the designated mortuary with the slab. Except that it wasn’t a slab; it was a billiard table, cast in the ubiquitous concrete (by those Italians, no doubt) and repurposed by my predecessor. The cotton-wrapped package that lay on it was unlabelled, and absurdly small. I unpicked the wrapping with difficulty and made the necessary check. A girl. The cord was still attached and there were all the signs of a rough forceps delivery. Forceps in a live birth are only meant to guide and protect the child’s head. The marks of force supported my suspicion that Laughton had been called at a point too late for the infant, and where he could only focus on preserving the mother’s life.

Night had all but fallen when I emerged. As I washed my hands before going to make a last check on our dying shepherd, I reflected on the custom of slipping a stillbirth into a coffin to share a stranger’s funeral. On the one hand, it could seem like a heartless practice; on the other, there was something touching about the idea of a nameless child being placed in the anonymous care of another soul. Whenever I try to imagine eternity, it’s always long and lonely. Such company might be a comfort for both.

John Petrie lay with his face toward the darkened window. In the time since my first visit he’d been washed and fed, and the bed remade around him.

I said, “Mister Petrie, do you remember me? Doctor Spence.”

There was a slight change in the rhythm of his breathing that I took for a yes.

I said,“Are you comfortable?”

Nothing moved but his eyes. Looking at me, then back to the window.

“What about pain? Have you any pain? I can help with it if you have.”

Nothing. So then I said, “Let me close these blinds for you,” but as I moved, he made a sound.

“Don’t close them?” I said. “Are you sure?”

I followed his gaze.