3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

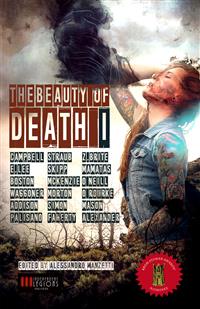

- Herausgeber: Independent Legions Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

The Beauty of Death Anthology, edited by Bram Stoker Award® Winning Author Alessandro Manzetti.

BRAM STOKER AWARDS 2016 NOMINEE - SUPERIOR ACHIEVEMENT IN AN ANTHOLOGY

Over 40 stories and novellas by both contemporary masters of horror and exciting newcomers. Stories by: Peter Straub, Ramsey Campbell, Edward Lee, John Skipp, Poppy Z. Brite, Nick Mamatas, Shane McKenzie,Tim Waggoner, Lisa Morton, Gene O'Neill, Linda Addison, Maria Alexander, Monica O'Rourke, John Palisano, Bruce Boston, Alessandro Manzetti, Rena Mason, Kevin Lucia, Daniel Braum, Colleen Anderson,Thersa Matsuura, John F.D. Taff, James Dorr, Marge Simon, Stefano Fantelli, John Claude Smith, K. Trap Jones, Del Howison, Paolo Di Orazio, Ron Breznay, Mike Lester, Annie Neugebauer, Nicola Lombardi, JG Faherty, Kevin David Anderson, Erinn Kemper, Adrian Ludens, Luigi Musolino, Alexander Zelenyj, Daniele Bonfanti, Kathryn Ptacek, Simonetta Santamaria.

Cover Art by George Cotronis

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

The Beauty of Death

Edited by Alessandro Manzetti

ISBN: 978-88-99569-18-1

copyright © 2016 Independent Legions Publishing

1 edition epub/mobipocket: 1.0 July 2016

Book Cover: George Cotronis

English Editing: Jodi Renée Lester

Digital layout: Lukha B. Kremo - [email protected]

www.independentlegions.com

The Beauty of Death

Table of Contents

BREAKING UP by Monica O’Rourke

THE CARP-FACED BOY by Thersa Matsuura

FATHOMLESS TIDES by Tim Waggoner

METAMORPHIC APOTHEOSIS by Rena Mason

CARLY IS DEAD* by Shane McKenzie

THE BITCHES OF MADISON COUNTY by John F.D. Taff

FINDING WATER TO CATCH FIRE by Linda Addison

GOLD by James Dorr

ABOVE THE WORLD* by Ramsey Campbell

MULHOLLAND MOONSHINE by John Palisano

WHITE TRASH GOTHIC EXCERPT by Edward Lee

ROTTEN APPLES by John Claude Smith

CALCUTTA, LORD OF NERVES* by Poppy Z. Brite

KOZMIC BLUES* by Alessandro Manzetti

ALLEY OOPS* by Del Howison

IN THE GARDEN by Lisa Morton

IN FRIGORE VERITAS by K. Trap Jones

THIS IS HOW WE LEARN by John Skipp

BLACK-EYED SUSAN by Mike Lester

DEARLY BELOVED by Ron Breznay

VESTIGE by Annie Neugebauer

PROFESSOR ALIGI’S PUPPETS by Nicola Lombardi

12 by Gene O’Neill

HOW TO MAKE LOVE AND NOT TURN TO STONE by Daniel Braum

CANDY* by Paolo Di Orazio

NO PLACE LIKE HOME by JG Faherty

THE OFFICE by Kevin Lucia

CONTRACTIONS by Kevin David Anderson

SEASON’S END by Colleen Anderson

THE RULES OF SILENCE by Simonetta Santamaria

EVERY GHOST STORY IS A GHOST STORY by Nick Mamatas

BUILDING CONDEMNED by Adrian Ludens

BY THE RIVER SHE WAKES by Erinn Kemper

THE CAPTAIN by Stefano Fantelli

THE DARK RIVER IN HIS FLESH* by Maria Alexander

BLACKER AGAINST THE DEEP DARK by Alexander Zelenyj

LARRIE’S TAPES by Luigi Musolino

COLD FINALE by Bruce Boston and Marge Simon

GAME by Daniele Bonfanti

BLUE ROSE* by Peter Straub

THE I OF THE BEHOLDER by Kathryn Ptacek

*Reprint

BREAKING UP

by Monica O’Rourke

The sun warmed the backs of their heads. In the chilly air, the sea-green fabric of Kathy’s bikini top rubbed against her nipples. Mitch stared because he couldn’t help it, not because he wanted to. After all, this was going to be the Big Breakup, although Kathy likely didn’t know it yet. Even her perky tits weren’t enough to make this onerous mess of a relationship work.

Waves exploded along the shoreline, droplets pelting the mossy rocks like shrapnel. The corroded pier jutted from the ocean like a handful of fractured fingers.

Kathy knelt in the sand and hovered over the blanket. Dark pubic hairs jutted from the edges of her bikini bottom in contrast to the bleached blonde on her head. She leaned back on her heels and pulled her hair into a ponytail.

She peered curiously at Mitch. “What are you thinking?”

He paused for just a second. “How much I want you,” he lied.

She shook her head, her eyes downcast. He flushed red, sure she must have been reading his mind, his mendacity not lost on her. Otherwise, why such a sad look? So suspicious. Unless he was being paranoid…

She smiled as she approached and dragged her tongue across his chest. Her fingers caressed his inner thigh. But then she raised her eyes, indicating their approaching friends, and slowly shook her head.

What the hell? He slapped her hand away, pulled away from her eager mouth and fingers. “Then stop, you dumb bitch,” he muttered. He sprinted across the beach and entered the water. He wiped the back of his hand across his forehead as the sweat dripped from his hair. The cool waves broke on his thighs.

He looked back. Paul and Marni had joined Kathy. His raging hard-on was under control. Mitch left the Bondi-blue water to join the others; they’d skipped Friday afternoon classes in favor of the beach. Classes during senior year were a joke anyway.

“I brought marshmallows,” Marni said, reaching into her pack. She and Paul had brought back sticks and were dangling them over the flames.

“Who cares?” Mitch muttered. He collapsed beside Kathy and wiped his face on a towel. She gently pressed her fist into his shoulder and gave him the look: stop being a jackass.

“What are we gonna do tonight?” Marni asked, snapping her gum, fingers intertwined in Paul’s thick black hair.

Paul laughed. “Waddaya think we’re gonna do tonight?”

They all laughed, except Mitch, who shook his head in disgust at Paul’s crudeness.

“Oh, Paul,” Marni laughed, slapping his arm.

Paul glanced at Mitch. “Lighten up, man.”

“Hey—sand fleas,” Marni said. That’s a real problem on the beach. Ever get sand fleas in your whatsit?” She giggled. “Itches like hell.”

“In my whatsit?” Paul said, laughing.

“Not you, dummy,” Marni said, laughing. “Guys don’t have whatsits…”

“We don’t have what?” Paul asked, leaning into Marni, teasingly flicking his tongue at her. “What is it we don’t have? Pussies?”

She blushed and tucked strands of hair behind her ear.

“Knock it off,” Mitch said, sitting up and then kneeling. “You’re a pig.”

“I’m just joking with her. What’s your problem? Lighten up, man,” Paul said. He stood and hitched up his baggy swim shorts, and sand spilled from the pockets. He wiped his hands across his knees and leaned toward the fire.

Mitch stared down at Paul, fists clenched, the sudden burst of angry heat on his face stinging his eyes. Paul really hadn’t done anything wrong, but it seemed everything annoyed Mitch today. He grabbed Kathy’s wrist and pulled her to her feet before saying anything stupid and pointless to Paul.

Besides, he had business with Kathy that he just couldn’t postpone any longer. He needed privacy. “Let’s go.”

“Wait—why?” She dug her feet into the sand and pulled back, jerking out of his grasp. “I’m staying.”

He waited a moment, catching his breath, and tried to regain his composure. His angry outbursts didn’t make sense, even to him. He knew it was the anticipation of the real reason they were here today, and he wanted to prolong the inevitable. This wouldn’t be easy. He knew that on some level, she had to know why they were here. She was almost as good at manipulating feelings as he was. Tears were usually her weapon of choice.

Without another word, Mitch grabbed her wrist and pulled her away. No one tried to stop him.

Kathy allowed him to drag her along and struggled to match his long strides. Eventually they walked side by side along the packed, moist sand a few feet from the breaking waves.

“What’s wrong with you?” Kathy asked quietly. She pulled herself out of Mitch’s grasp and pretended to brush invisible lint off her arms, her bikini.

Mitch brooded for a moment. “We have to talk.”

Kathy laughed, but he saw her flinch. It had been a slight movement, evanescent, but he’d caught it. She swallowed hard. “No we don’t.” She licked her chapped lips and took off ahead of him. “Catch me!”

He didn’t bother. She raced a few feet before glancing back, and when she realized he wasn’t in pursuit, she slowed down.

Suddenly he realized he was always disappointing her. As annoying as she was in this relationship, she wasn’t the hurtful one, the one who caused the pain. What a rude awakening that was for him. Still…when did a day at the beach get so damned serious? He tried to push the thoughts out of his mind and focused instead on the hot girl a few feet away. He pushed away thoughts of gentlemanly behavior and zoomed in on her ass.

They climbed a low dune. When they reached the other side, he swiveled and kissed her roughly, his tongue probing her mouth.

She seemed startled by his sudden movement and took a small step back.

But she never refused him. He often wondered why, knowing his brutish behavior often crossed lines of decency. Still she did what he wanted. Always. Made him wonder what her home life was like, but he never wondered for too long.

We have to talk. Wasn’t that hint enough? She had to know what that meant. She’d had many boyfriends before him—surely she’d said or heard those words many times before.

He pulled her close and lifted the thin fabric of her bikini top, exposing the small breast. He licked the rock-hard tip, and she moaned and ran her fingers through his hair.

She knew what he liked, and she felt good to him, familiar, safe, someone he enjoyed being around, but she wasn’t someone he imagined a future with. Their relationship felt destined to be short-lived. It seemed she did what he wanted in an effort to keep him, though she had to know that was fruitless. He wondered what it would take, ultimately. He wondered how to do this without devastating her. He wasn’t an animal; he had feelings. Sort of.

He reached around and unfastened the hook on her bikini top, her pale skin illuminated in the diminishing sunlight as she stepped out of the bottom piece.

He admired her body for a moment, caressing and sucking her breasts, and gently rubbed the triangle of pubic hair between her legs.

She pulled his swim trunks down, and he stepped out of them.

They collapsed against the dune, listening to the waves shatter on the rocky beach. He felt guilty about the impending breakup, but not enough to stop fucking her. He’d brought her to this deserted strip of beach for privacy. Bringing Marni and Paul hadn’t been Mitch’s idea, it had been Kathy’s. She always managed to ruin everything, and now she was even managing to screw up their breakup. He was sure she’d brought them as backup, perhaps expecting them to prevent Mitch from dumping her.

Still, sex always made up for her stupid mistakes.

“You’re hurting me,” she said, pushing at his chest. She reached between her legs, and her fingers adjusted his cock. He was just about finished anyway.

“Too rough, Mitch,” she whined, wiping carefully at her thighs. “Like sandpaper.”

This wasn’t his fault; it was the goddamned beach. “You’re too sensitive.”

“No, stupid—too much sand. Not even a towel.”

He’d pressed her into a dune, and the sand trickled down her shoulders and cascaded across their sweaty bodies. Now he collapsed against her as he came, breathing hard on her shoulder. Grains of sand left a light coating on his damp skin, jumped into his nose and eyes.

She frowned and folded her arms across her naked chest. “That hurt.”

He didn’t know what else to say. “Let’s head back. We’re losing light.”

“No we’re not. It’s still early.” She hopped around a bit and spread her legs. “That really hurt!” She patted her crotch, wiped away sand, even folded back her vaginal lips and tried to wipe them clean.

Her movements looked absurd. “What do you want me to say?” he yelled. “It wasn’t my fault!” Now he was being blamed for sand? For the beach? Now he remembered why he so desperately wanted to dump her. She was a selfish idiot. Sex wasn’t worth this, no matter how good.

He grabbed her hand and pulled her up. “Let’s go.”

“I need to jump in first.” She pointed at the ocean and pouted. “I want to wash this sand out.”

“When we get back.” He handed her bikini to her.

“I just want—”

“Let’s go.”

She dressed quickly while he stepped into his trunks. They walked back in silence, her a few feet ahead, searching for oddly colored shells in the gray sand of the shallow tide.

When they reached the blanket, Paul and Marni were gone. The fire had died down to a few smoldering sticks. Mitch poked it with a twig, hoping to get it going again.

He cupped his hands over his eyes and scanned the beach. “Just goddamned great,” he said, exhaling dramatically.

Kathy sat at his feet and took over trying to revive the fire.

“They have some fucking nerve,” he whined, “taking off like that.”

She shrugged, looking toward the road. “Car’s still there.”

“Damned straight the car’s still there. He’d be a cripple if he took off without us.”

“So what’s the problem, babe?”

“Problem? It’s rude, that’s the problem. They’re off screwing in a bush somewhere and I want to get going. I’m hungry.”

“Me too.” She reached across the blanket and snatched Marni’s bag of marshmallows. They were coated in sand. “Oh, yuck,” she said, trying to dust one off.

He rolled his eyes and faced the ocean. The beach seemed smaller, but it was high tide—the beach was smaller. He squatted beside a dune. The sides cascaded down in a series of tiny avalanches.

A few moments later he joined Kathy on the blanket. Nearly twilight. In the diminishing daylight, the stars became more visible and peppered the sky like scattered grains of sand. They huddled near the fire and watched the ocean.

“You think something happened to them?” she asked.

“Who knows. Maybe they fell asleep somewhere.” He rose to his feet, cupped his hands around his mouth, and shouted for Paul and Marni.

The only reply was from the ocean, its roaring crash resonating over the sand, a fine salty mist clinging to the air like a heavy and cloying perfume.

“You think maybe they drowned?”

“I don’t know,” he snapped, falling back to the blanket, puffing into his cupped hand. He looked at her incredulously. “Both of them?”

“I don’t know. Maybe Marni was drowning and Paul tried to save her and—”

“You’re being dramatic. Shit like that doesn’t happen.”

“Maybe we should call the police. We can come back.”

He nodded, but there was no cell reception out here. “Where’s the nearest pay phone, do you think?”

“I didn’t see one around here. We passed a Citgo station a few miles back. Or maybe once we drive, we’ll get a signal on our phones.”

“Okay, good idea. Let’s go.” He stood. “Pack up. I’ll start the car.”

“Don’t leave me alone here, Mitch!”

He shook her off his arm. “Don’t be stupid, Kat.” He smacked the sand off his ass. “Why are you acting like an idiot? There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

She got up quickly from the blanket. “We should leave everything here. In case they come back.”

He nodded, and reached into Paul’s sneaker to grab the keys. He headed toward the car parked some thirty yards away, Kathy trailing closely.

He opened the driver’s side door and was immediately concerned when he didn’t hear the familiar buzzing. He pulled the door open, and the interior remained dark. He stuffed the key into the ignition and tried to start it. Nothing happened. No clicking, no attempts by the engine to turn over.

He turned sharply toward Kathy, who was sitting shotgun. “When you came out to the car earlier, what did you do?”

“Do?”

“Do, do! When you came out earlier, were you playing with your makeup in the mirror? What were you doing?”

“Nothing!”

“Did you turn on the dome light?”

She didn’t want to answer. “Dome light?”

He pointed at the ceiling. “The switch is on, yet we have no light. How can that possibly be?” He peered into her face. “Did you turn anything on when you came out to the car?” His mouth was a lipless tight line, and his jaw muscles worked furiously.

She swallowed, and tears rolled down her cheeks. “I don’t know, Mitch! I can’t remember!”

“Fucking battery is dead.” He got out of the car and slammed the door.

She followed him out. “Why don’t we just wait in the car?”

“Do what you want,” he said, heading back to the beach.

She chased after him. “Please don’t be angry. I didn’t do it on purpose.”

They returned to the blanket. Still no sign of Paul or Marni.

“I know you didn’t do it on purpose.”

She sat cross-legged at the edge of the blanket and prodded the smoldering fire.

“Tide’s moving in,” he said, and again, the beach looked smaller.

“I didn’t know it moved in this late,” she said, staring curiously at the water, almost hypnotized by its movement.

He shrugged. “I dunno. I guess.”

“I think I can get this going again.” She added twigs, touching a match to them. “This is romantic, isn’t it?”

He sat beside her and frowned. He licked his lips and shook his head as if trying to choose a gesture. “I guess. Under different circumstances.”

“Come on.” She pulled him toward the blanket. “Maybe they’ll come back. Let’s just lie down. You can hold me, keep me warm.”

He scanned the area one last time, guided by the moonlight reflecting off the dunes. There was no sign of life for miles.

He lay on his side, his knees pressing into the small of her back. He draped his arm across her shoulder, slipping his hand up beneath her sweatshirt.

She snuggled closer to him. “This is weird, isn’t it?”

He said it was.

“It’s funny what the water can do, isn’t it?” she asked softly, her breathing steady, as if close to sleep. “Play tricks and all.”

“Uh huh,” he said breathily, slowly lulled into semi-sleep, but then his eyes opened and he asked, “What do you mean?” They gently closed again, and he was mesmerized by the sounds of an endless ocean, lulled by the gentle tone of her voice. Invisible fingers stroked his hair…

“The dunes,” she said sleepily. “Seems like there’s more of them.”

His eyes opened and he frowned, thinking for a moment. “You noticed that?”

“Mmm…” She didn’t exactly answer. The rhythm of her breathing slowed, evened out.

He rubbed his hip, which had begun aching. “What are we lying on?”

“Hmm?”

He climbed to his knees and she rolled onto her back.

“Help me move this blanket,” he said.

“Can’t we just smooth it out? I don’t want to move it. The fire’s keeping my feet warm.” But she got up, and they tried to smooth out the lumps.

“It’s not working,” he said. “Move over.”

He pulled the top of the blanket down. “Look at this. No wonder. It’s like lying on a lumpy mat—” He suddenly pulled back his hand.

“What is it?” She gasped.

He laughed. “Just a chunk of wood. For a second…”

“What? For a second what?”

He smiled. “Nothing.” For a second it felt like an arm…

He pulled her back into his arms, and she lay on her side, her head resting on his forearm. He stroked her hair, mesmerized by her scent, like baby powder and sunbaked wildflowers. For a moment he wondered why he wanted to break up. It really wasn’t her fault, he considered in a moment of kindness and clarity. Being tied down was a problem for him, and even with someone wonderful, it was still a noose around his neck.

He was young, and he wanted his freedom. Does it matter? he thought. Even if he was going to break her heart, did it matter? They were eighteen, the lot of them. No one gets serious at eighteen.

He closed his eyes and stroked her hair, breathing in her smell, the softness of her skin like a security blanket. He nuzzled her ear and pulled back when grains of sand tickled his nose. More sand spilled over his face, and he opened his eyes.

An enormous sand dune had formed.

Mitch glanced at it. This was impossible. There was a breeze, sure, but not enough to create a six-foot-tall wall of sand. It stretch out about ten feet in either direction. He would have heard movement if it had been Paul and Marni building this thing to play a trick on them.

He was suddenly too afraid to move, and he found that ludicrous. This was the stuff of low-budget horror flicks, not something that ever really happened.

“Kathy?” he whispered, but she was sound asleep. Why had he whispered? But when he opened his mouth to shout, nothing came out. His brain refused to cooperate, refused to allow him to raise his voice.

He stared at the dune, and it remained transfixed…but if he looked away for the briefest second…it seemed to move toward him. As crazy as that was, the damned thing seemed to be approaching. Tired eyes, he thought, rubbing the sleep out of them one eye at a time. But even then the dune remained unchanged, didn’t fade back into the beach, didn’t collapse like a no-longer-needed golem.

The dune stood between him and the path leading toward the parking lot. Away from the beach.

Mitch slowly climbed to his feet, trying not to blink. He tried to call Kathy’s name again, but his mouth was as dry as the dune.

This was impossible. Things like this didn’t happen. Not really. Wasn’t there always a reason for everything, no matter how anfractuous? Nothing was ever as it seemed, not really. Maybe he could blame this on a trick of the light, something wrong with his eyes, on moonbeams and rising tides. Something. There had to be a reason.

He tripped over something and landed hard on his ass, his eyes briefly shutting. He quickly opened them.

The dune had shifted again.

Now it was half a foot from Kathy.

“Kathy?” he croaked, still leaning toward decency, toward rescuing his girl despite the insanity playing out before him. Part of him wanted to pull her into his arms, away from the beach, away from dunes, away from the ridiculous situation at play.

But she wouldn’t answer. Goddammit, she just lay there! How was he supposed to rescue her if she didn’t cooperate? No, this was her fault now, not his. He tried. He did everything he could. He—

“Mitch?” Kathy stirred, raising her head, looking from side to side. “Honey?” She tilted her head backward, craning back over her own neck, and for a second…for a second it was an optical illusion…for a second Mitch saw her head severed from her body, a flawless, bloodless cut, and he swallowed hard. It burned from the effort. Grains of sand danced down his throat.

“Ka…,” he croaked, not even able to finish saying her name. His throat was dry but his armpits and hands were damp. He slowly reached out to her, but he didn’t move.

Neither did she.

She seemed transfixed, as if on some level she knew to stay still, though that made no sense to Mitch. Unless she sensed something, sensed trouble.

She moved a bit, leaned forward, now resting on her hands and knees; she cocked her head as if to hear him better. “What’s wrong?” she asked. “You okay?”

He slowly shook his head.

“You’re scaring me.” She moved to stand up.

The dune shifted with her.

“Wait!”

She stopped, clearly startled. But now she looked annoyed, likely wondering what sick game Mitch was playing.

“Don’t move,” he urged, begging her with his tone. The frustration had built so intensely he wanted to scream, to shriek, to smash his fists against a wall. Adrenalin filled his veins and froze him to his spot.

She looked around for something out of place, anything to indicate Mitch’s strange behavior. He could see the expression on her face, and he didn’t know how to explain to her what the danger was. Just don’t move, he thought. How could he explain this? He’d think of something. After all, he was the man. He was supposed—

But she took a step toward him.

“No!” he cried, taking half a step toward her.

She froze, a reaction to his command. The sand from the dune cascaded gently around her feet, just a small hill of sand spilling down its own side…something so innocuous…nothing to worry about. Nothing to see here.

“What’s that?” Kathy asked, pointing a few feet from Mitch. She still wasn’t moving, but now it seemed she had a different reason to stay away from him.

He glanced down. A human hand stuck out of the soft dirt, exposing long, thin fingers, the nails painted a bright neon purple. “Jesus Christ,” he muttered.

He backed up several steps.

“Is it Marni?” she shrieked. “Is it Marni?”

Sand slid away, as if a giant fan had suddenly been switched on. It drifted away grain by grain, slowly cascading outward, revealing the body piece by piece. He peered into the shallow grave and discovered it was indeed Marni. And lying just below her was Paul.

Kathy fell to her knees.

Neither moved for several minutes. He wondered if the sand had settled now…if it would let them leave. Let them. He shuddered and looked up again at the dune. It had spread a bit, not as high, but it was wider, and it formed a semicircle around Kathy.

It almost seemed to challenge him to approach.

I can’t, he thought. I can’t do this.

It wants me to come closer.

He had no idea why he thought that.

If he could reach Kathy, maybe he…maybe he what? There was no way around the dune to the parking lot. The ocean was behind him. He could leave. He could leave Kathy.

He took half a step back, and she cried, “Don’t you leave me!”

He stopped. “Then come here! What the hell’s your problem?”

She looked down at her feet and back up again. “I…I don’t know. I’m scared.”

Now full of bravado: “Of what? Don’t be a chickenshit. Come here.” Come here. Oh GOD, come here! He forced a smile. But a small voice inside him whispered, No, don’t. Just stay.

She took a step toward him, hands reaching, fingers desperately trying to connect with his even several feet away. Her breath caught in her throat as she sank just a tiny bit with every effort she made.

The sand quickly began to swirl, and rippling jetties formed beneath her feet. Small pockmarks puckered the sand, quickly grew into sinkholes, and her feet were slowly swallowed up by the forming black holes.

“Mitch!” she shrieked, trying to lift her feet, to move toward him. With every step she sank a bit lower.

“Stop moving!” He had nothing to use as a rope, nothing to offer her, like a tree branch or towel, nothing for her to hold on to.

“Please, Mitch!” she sobbed.

He watched the dune consume her. Watched the sand spill over her body, great waves of dirt covering her, a dry drowning. He watched the terror in her eyes as the dune moved in, engulfing her, taking her inch by inch into the black hole it had formed. It wrapped her in a great wall of sand, like a lover’s embrace, caressing her almost lovingly, tenderly, laying her down gently, stroking her hair with fingerless hands, pulling her beneath the surface so she could rest eternally with her new lover.

“Kathy!” But he knew he’d overstayed his welcome. He turned to flee, taking advantage of the death of his girlfriend, turning from his dead friends and from the car, from the dead battery, thinking now of the ocean, forgetting the road to safety that was anything but. He was a strong swimmer. He could swim for it and pray the sharks wouldn’t get him. He could do this.

He whirled around to face the water, to retreat in that direction, to jump into the ocean, to escape the dune.

But the water was gone from sight now, replaced by an enormous wall of sand.

THE CARP-FACED BOY

by Thersa Matsuura

Horse and Bones—

Grandpa Tetsu squatted behind the rustling curtain of a willow tree, his near-crippled hands weaving horseshoes from lengths of stiff straw. With the completion and knotting off of each row he squinted over at the one-storied, thatched-roof house—paper windows and doors thrown open to catch the breeze—to check if his family was sneaking up on him again. He needed to keep his distance, especially now that his daughter had returned; and she wasn’t alone.

For weeks he’d been battling a thorny ache inside his chest. It felt like the deep end of hunger, or possibly a warning. And then two nights ago, through the sheeting rain, he’d heard the neighing of a pained horse and with it a baleful cautioning only his keen ears could detect. He’d let his wife welcome his daughter and her son—the most unwelcome of guests—while he fell back asleep certain that something very, very bad was going to happen soon.

There was the sound of feet slapping wooden floors, but still no one came outside. The horse beside him shifted uncomfortably on its spongy hooves and Grandpa Tetsu reached up and patted its ribbed belly. What kind of monster rode a limping horse all the way from the city in the pouring rain, until its shoes tattered and fell off?

The old man stood, balancing himself with one hand on the animal’s sunken back. He stretched and slapped at the kinks in his crickety legs. Used to be he could stand most hours of the day, walk to Takakusa Mountain and back, and never tire. But that was a long time ago. He retrieved his wife’s tortoiseshell comb from his sleeve and carefully began working the knots out of the creature’s matted mane.

“Good boy.” Grandpa Tetsu inhaled the dusty, sweaty-warm odor of the animal and the knot in his chest eased. “At least she brought you.”

The shrill scream of a child came from the direction of the house. Movement and laughter. The old man ducked. He watched as his wife and daughter burst from the open door and marched over. They planted their baskets of laundry not more than a stone’s throw away from where he stood crouching behind the horse’s nervous legs. Not noticing him, the two began pulling water from the well. The child, strapped to his mother’s back with long pieces of soft cloth, squirmed and kicked his chubby legs. It looked as if he might be in pain. Or possessed. The thought lingered a little too long, and almost as if he’d heard it, the boy stopped, turned, and looked directly at his grandfather. Something poisonous passed between them. Grandpa Tetsu shuddered and fell back against the tree.

He’d been seen by the carp-faced boy.

It was unnerving: eyes goggling, startled wide; long, wet lashes. Grandpa Tetsu had never seen the child blink. Not ever. That must mean something. Then there was the mouth, thick lipped and down turned, every now and then popping open in that desperate famished way of the candy-colored carp in the pond. When he first saw the child last spring, the old man had expected him to speak, to form a sentence or two, to say something frightful or wise. But no, instead, from the empty cavity spilled only a long line of drool or when disgruntled the occasional howl. An ear-splitting, unnatural cry that continued until those heavy sagging cheeks splotched red and a more awful-colored substance oozed from his nose. Something about the child was all wrong.

In an effort to stay calm, the old man pulled loose the pouch tied around his waist and placed it on the ground between his legs. He wriggled his entire fist inside, retrieved a handful of fish bones, and stuffed them into his mouth. Slowly he chewed. The briny-salt taste tightened his cheeks and jaw. His appetite flared. Fat, fish-faced child, he thought, leaning forward, daring another look. The boy continued to stare, turning his head every time his mother moved so as not to lose sight of the old man. What was he thinking? After a moment, the toddler’s thick arm flailed and steadied, pointing in his direction. An icy claw gripped the back of Grandpa Tetsu’s neck and he pushed himself flat against the tree once more.

And why was he so fat anyway? When the entire town was fighting to put something in their belly, what was that ugly boy feasting on? Grandpa Tetsu filled his mouth with more bones. Worked them angrily between his jaws.

“When all I have to eat are these.” But with the mumbled words his mood lightened slightly.

It was his best-kept secret. Grandpa Tetsu was the town’s elder. Old and healthy, he was revered for his exceptional luck. During his entire life he’d not so much as suffered a broken bone, even that time he fell off the roof last winter and landed on his head. The most remarkable thing, though, was the fact that he had never lost a tooth. Everyone else his age spent meals mashing watery sweet potatoes between tender gums. Not Grandpa Tetsu. Almost daily townspeople stopped by to discuss the weather and ask his advice on health and long life. And almost daily Grandpa Tetsu told them lies.

He thought that telling the truth lessened its power. So the paper seller with the persistent cough was told to stir cicada husks into his morning soup, and the geta maker’s wife with the full-body rash was instructed to make a tincture of the lizard’s tail plant and early morning dew and apply it to the infected areas. Strangely, most of the remedies worked.

His real secret, though, was fish bones. Collected from the garbage after meals and roasted a second time over warm coals until they cracked and blackened. He sprinkled them with sea salt and kept them in a cloth bag around his waist. He ate them whenever the hunger pangs came. Which very often occurred in the middle of the night. The thought of nighttime led his thoughts to what had happened the previous one—when his daughter and only grandchild had slept under the same roof.

A sound? A weight on his chest? He had bolted upright, blinking in the dusky glow of the andon lamp, puzzling at what had woken him so suddenly. He listened hard expecting another warning, but heard only the whir of insects and the erratic dry snore of his wife in the next futon. There was a draft, so he turned, his eyes adjusting to the gloom. There he saw the bedroom door pushed open, and sitting in the hall, skin dyed orange and jumpy by the oil lamp, leaking piteously from an open mouth: the carp-faced boy. At the memory Grandpa Tetsu’s mood returned to its recent sour state.

“Horsey!”

Grandpa Tetsu jumped, scratching his back against the rough bark of the tree, his feet kicking the half-made horseshoes and his bag of fish bones. There under the horse’s chest the child wobbled on his grotesque legs, his curious eyes, his mouth turned into a fishhook smile.

Grandpa Tetsu’s wife laughed and trotted over. “Ojiichan, what were you doing? Did you scare yourself again?”

“Horsey!” the child insisted, raising his plump arms toward the animal, squeezing his sticky hands into fists and releasing them over and over. No doubt recognizing the danger, the horse whinnied, stepped back, and tossed its head. The child’s mother scooped the boy up.

“Don’t put him on the horse,” the old man demanded, standing slowly on painful legs. “He’s too fat.”

“Oh, he’s just a baby,” the old man’s wife said. She reached over and pinched one of the loathsome baggy cheeks. “And the horse carried them both only yesterday.”

Grandpa Tetsu moved around so that the horse was between him and the toddler. “Just don’t.”

The child kicked and arched his back and his mother plopped him down in the dirt, letting him fiddle with the straw horseshoes.

“And he shouldn’t play with those either,” Grandpa Tetsu said. And then realizing he had his daughter’s attention, he continued with the lecture he’d been building up to. “Look what you did.”

He lifted one of the horse’s rear legs showing her the sad state of the hoof. “We’re lucky this animal didn’t go lame. It’s a good thing the sun came out and dried everything up. Hopefully they won’t rot.” He kicked at the dusty ground.

The old man’s wife and daughter exchanged a glance. His wife spoke.

“We should be thankful that they are fine and were given a horse to ride. There have been terrible stories recently of men on the roads—”

“What are you doing there? You!” Grandpa Tetsu interrupted. The toddler had given up the straw horseshoes and was placing small rocks one on top of another. “Only people trying to flee purgatory stack stones. Why is he stacking stones?”

The old man stormed over, grabbed the horseshoes and his fish bag, and returned to his place on the safe side of the horse.

“Oh, why don’t you play with him, Dad? He’s very, very smart,” his daughter said.

“He is,” his wife agreed. “And he adores you.”

Grandpa Tetsu refused to answer. Instead he turned up the bag and shook the remaining fish bones into his mouth. He chomped down hard and screamed. Pain cracked down his jaw and neck.

The surprised horse kicked up its rear legs, just missing him, and danced sideways blowing air from its nose. The boy sitting under the dancing, blowing creature giggled and clapped his hands. His mother took him into her arms again and petted him as if he were the injured one.

Grandpa Tetsu collapsed to his knees, spitting on the ground. The splintering pain clung inside his skull. With his mouth still open, a line of spit connecting him to the earth, he used one trembling hand to dig through the pile of unchewed bones. When he found what he was looking for, he pushed himself up and held his palm out for his wife and daughter to see.

“Look!” he demanded. “Look what that child put in the bag!” There between his thumb and forefinger, a stone; next to it, three teeth cracked in half and a pool of watery blood.

Pain and Bargain—

After that Grandpa Tetsu shut himself inside the tearoom and wouldn’t come out. For two days he refused visitors and left his meals untouched. His only sustenance was small sips of warm tea he slowly maneuvered down his throat by comic head movements and the sweet tobacco he constantly smoked in his long kiseru pipe.

The room reeked of blue smoke and unwashed old man. But despite his wife’s nagging, he opened the thick-papered windows only when he needed to relieve himself or when he wanted to observe the horse, listen for any more whinnied advice. It was the horse that had warned him. The only one he trusted now. Mostly Grandpa Tetsu spent the days moaning and mumbling to himself.

The pain fluctuated from the cut of a newly sharpened knife to a dull thrum that caused even his toes to curl and tingle. But it wasn’t the pain the old man was worried about. What was more terrifying were the ragged tears in the sliding doors that led to the hallway, and how sometimes through these holes there appeared eyes, eyes with long, wet lashes, eyes that didn’t blink.

“Keep him away!” he’d shout, knowing how vulnerable he was. “Just let me die in peace.”

Once Grandpa Tetsu flung a vase at the eyes, but it only clattered across the wooden floor of the hall, leaving a larger gash in the paper. That evening a frowning mouth appeared, opening and closing, and gulping for air. It looked hungry and Grandpa Tetsu prayed his dying would come quicker.

On the morning of the third day his wife brought him more tea, tobacco, and news.

“Today I heard some interesting gossip,” she began.

The old man groaned. Earlier he’d opened the window and now lay on his side staring at the willow tree watching the horse nibble the leaves off the thin cascading branches. The beast was suspiciously quiet today.

“I heard there is a visiting craftsman from Yukifuru Mountain, Gingumo Temple. His name is Nakanishi and he used to carve Buddhist statues. He excelled in the One-Thousand Armed Kannon. They say he is practically a legend.”

She waited for a response. Grandpa Tetsu scratched at a spider-webbing itch on his thigh instead.

“This past spring he gave up carving Buddhist statues and began a more practical, slightly unconventional, and some say much more lucrative profession—he carves false teeth now.”

The old man grunted.

“They say that his teeth are made from only the finest woods and are stronger and more comfortable than even your own teeth.”

Grandpa Tetsu huffed and sat up, facing his wife.

“Too expensive,” he mumbled.

“Yes,” she said, lifting the top of the teapot to check the leaves and then replacing it. “We’ve been looking for something we might be able to trade for his services.”

“There’s nothing,” he said, readying to lie back down.

“I was thinking about the comb my grandmother gave me, the tortoiseshell one, but when I took it out three of the teeth were broken.”

“That child again I bet,” the old man said. “Always snooping around, getting into things.”

“He’s just a baby.”

“Maybe,” Grandpa Tetsu said, an idea dawning on him. “Every craftsman needs his own apprentice, someone to train from an early age.”

“You’re much too old to learn a new trade. And you know how bad your eyes are.”

“Not me.” He looked over his wife’s shoulder at the doors that led to the hall. Today there were no eyes or mouth or small clutching hands trying to get in.

“What are you talking about?”

“Two birds, one stone. Perfect payment. You said yourself the child was smart. We barely had enough to feed the two of us when they showed up. He’d have a very good life. Besides, what is a child without a father anyway? He’d be paying me back for the teeth he broke.”

“How could you think such a thing?” His wife stood and shook her head down at her husband. “I would never allow that.”

“Humph,” the old man grumbled, arms across his chest. “Just you wait. I know, I’ve been told. If we don’t get rid of that child something terrible will happen. Something worse than this.” He motioned to his swollen mouth.

“Who? Who told you such a thing?”

Grandpa Tetsu didn’t answer. Instead he reached for the teapot at the same moment his wife moved to take the tray away. Their hands touched.

“You’re burning up with fever.” She pulled her hand away and rubbed it.

“Ridiculous. If anything, I’m cold,” Grandpa Tetsu said. “And if I do have a fever he probably gave it to me.”

“You’re impossible. Why do you have to make everything so difficult?” His wife turned on her heel and left the room, her soft steps beating quickly down the hall. He heard her turn and enter the kitchen, heard the slide and slap of the fusuma door shutting behind her.

“Well, then you had better make sure you keep him away from me!” Grandpa Tetsu called. The old man shook his fist twice before turning his attention back to the horse pawing the ground under the willow outside the window.

Wood and Teeth—

Two feet in wooden geta crunched the gravel outside. The pause between each footfall a count longer than any normal man’s pace. Long strides, weighted strides. He was tall. Even the heavy material of layered robes found Grandpa Tetsu’s ears. Not the roughly hewn, patched cloth of a villager—resonant folds, but a fine weave. A man of wealth. Importance. He was carrying something.

Waiting.

“Nakanishi-sensei has arrived,” his wife announced, leading the guest into the six-matted tearoom.

Grandpa Tetsu did not look up. The presence at his back was enormous, unmoving on solid feet, eating up the air around it. There was the click and slide of a tray being set down, a ceramic teapot, two cups, two plates on which he heard the clumsy shift of homemade sweetmeats—one by one the items were removed from a tray and placed on the old, veined wood of the low table. Still the ghost of the stranger leaned in. It tried to whisper in his ear, made the skin on the old man’s back crawl. Outside the sun was high; cruel today, it baked even the shadows and trembled the long tendrils of the willow.

Under the willow stood no horse.

“He’s been like this.” His wife offered an attempted apology. Her embarrassment normally would have angered Grandpa Tetsu. But he didn’t care. Not anymore.

He listened as his wife bowed her exit. And then he turned, keeping his head low, his eyes down.

“Thank you for coming,” Grandpa Tetsu mumbled as he bowed deeply, his forehead touching the matted floor; a hot river of blood pounded his head, burned the nerves in his crumbling teeth, and darkened his vision. He sat up, blinking away the ink in his eyes. He nearly lost his balance again.

“You are very welcome.” Nakanishi gave a slight tilting of his great head.

The stranger’s skin was a rubbed angry red, his nose long. He had hair the color of stringy clouds and a slate gray sky. It was long and tied high behind his head, the furrows of a fine-toothed comb were still visible. The same-colored beard fell all the way to the intricately braided cord looped around his waist and tucked into his obi. His eyes were copper.

“I am Nakanishi. They call me the carver-dentist.” He set several bags and a large wooden box on the floor. “Please lie down. I’ll examine your mouth.”

Grandpa Tetsu felt a seeping sense of relief at the stoop of the stranger’s shoulders. This suggested humility and diligence at his craft. This was a good man, a good dentist. And yet he was obviously powerful. Surely he’d recognize evil if he saw it. If he saw the carp-faced boy, maybe he could stop whatever plight was bearing down. A warm spot of hope fired in the old man’s chest. This stranger dentist would help him, could save him, from his deluded family and the evil carp-faced boy. But how to ask?

Nakanishi used a small mirror to catch the sunlight and direct it into his patient’s mouth. Fingers cool on his jaw, moving his head this way and that. Fingers that knew every detail of the Buddha’s face, the old man thought.

“You’re having much pain?” The carver slipped the mirror back into his sleeve.

“Yes, terrible pain. I haven’t eaten. I can barely drink. I’m haunted.”

“I’ve heard a rumor that with my teeth you can eat anything you’d like. Even things you couldn’t eat before.”

“Fish bones?”

Nakanishi paused, then laughed. “Ah, so that explains it. I was going to ask how you obtained such a fine set of teeth. Except for the unfortunate ones of course.”

“Stronger than anyone in town.” The old man bit down out of habit and winced from the pain.

“I’ve seen a lot of teeth, and for your age I think these are clearly the strongest, most healthy ones I’ve ever set eyes on.”

The old man smiled at the acknowledgement of his worth.

Nakanishi withdrew a long white rope from a bag and tied back his sleeves. His movements were certain and quick. He opened the box and began removing bundles wrapped in colorful cloth. Through the thin paper doors came the smell of millet boiled in a bit of rice. At the thought of having new teeth that were stronger than his own, the old man’s appetite returned.

“It does smell delicious, doesn’t it?” Nakanishi said, reading his thoughts.

“Before I begin, I thought you might be interested in seeing this. It’s my latest accomplishment.”

He untied the smallest bundle. Wrapped inside two sheets of paper he revealed a pair of wooden false teeth. They were beautiful.

“This set is going to a feudal lord.”

The carver held the teeth out, turning them for the old man to see. It was then that he noticed and gasped.

“That’s right. The four front teeth are real.” The carver-dentist tapped them with his fingernail. “That’s what brought me to your small town in the first place. Otsubo.”

Otsubo was the crazy man who used to live in a shack behind the town’s only basket weaver.

“When I heard about his accident I came right away.”

The accident was the talk all around town. Otsubo used to claim that every evening after his bath a fox visited him. One night he tossed a piece of abura age out in the yard and watched as the creature gobbled up the treat and immediately turned into a beautiful woman. The woman then began to entice him with her dancing and other female charms. Otsubo was elated, but every time he tried to approach the creature she would dash off into the forest. This happened for three nights in a row until he ran out of deep-fried tofu and had no means to get any more. On the fourth night, Otsubo hid and waited for the fox to appear. When it did he threw a large basket over the creature, thus capturing it. But after some time, listening to the pitiful cries of the lady inside, he lifted the basket to peek. That’s when instead of a white-skinned maiden he was met with a wild blue-faced oni who chased him through the town and right off a small cliff.

“Those are his?”

The carver nodded, wrapping the teeth in paper again.

“The only thing more expensive than boxwood teeth are real teeth,” the carver said. “I wanted to show you the quality of work I do. Now, lucky for you, it looks like I’ll have to pull only three teeth. I’ll replace them with something that looks like this.”

He removed a couple of small wooden chunks from another pouch.

“Real teeth come at a very high price but this wood is durable and will last a good long time.” He handed them over for the old man to examine. “Just look how attractive that grain is.”

“Smooth,” Grandpa Tetsu said.

“They won’t split or splinter. I’ll carve them to fit after I get rid of those bad teeth and take some measurements.”

Nakanishi removed a glazed earthenware jar and two small cups from one of the bags and placed them on the table next to the tea and snacks.

“I was given this by a saké maker in a small town near Edo.” He uncorked the bottle and filled both cups with the cloudy white liquid. “Behind his home there is a waterfall and a river so deep and clear you can see straight to the bottom. The children say if you sit at the water’s edge and stare quietly you can watch the kappa play on the riverbed.” Nakanishi handed him one of the tiny cups.

The old man laughed. “I haven’t seen a kappa in ages.”

“The pure water is what attracts them. It also makes for the best saké.”

Grandpa Tetsu turned up the cup and finished it in one swallow; the cold lacerated his jaw and head. “That is good.” The carver refilled his cup and left the top off the jar. “Do help yourself. It’s included in the price of the teeth.” He drank his own cup down.

The old man poured himself another, feeling a little sad when remembering the cost of his three teeth.

“Yes, she’s a good animal,” Grandpa Tetsu said. “She almost went lame after my daughter rode in on her. Stupid girl doesn’t even know how to change a shoe. How’s she doing for you?”

“She’s doing well. I left her back where I’m staying. The innkeeper said he’d wash and brush her for me. Tomorrow I’m leaving to call on the feudal lord.” He tapped the box where he’d replaced the paper-covered teeth.

“That’s good. She deserves the best. I’m sorry I got to know her for only a short time.”

“I’ll take good care of her.”

The old man drank another cup of saké, felt his head take a little dive. He watched as the dentist spread out a clean cloth and remove various metal instruments from the box: long-handled and short-handled scissors, several different sized pliers, tweezers, pointy needle-like tools, curled lengths of wire, and a miniature serrated hand saw.

“You’re very lucky, you know,” Nakanishi said, sharpening one of the needle-like instruments.

“I am?” The old man reached once more for the saké jug. Maybe he was right, it almost felt like his luck was returning.

“I won’t need half of these. Today’s procedure is simple.”

“Oh, good, no pain.”

“What I’ll do is remove all the broken pieces first. I can use the surrounding teeth as anchors for your new ones.” He lifted the wire. “They’re very strong and will secure the new teeth perfectly.”

Grandpa Tetsu gloated again at the compliment. “Yep, strongest in the entire town.”

“I’ve never seen such fine teeth. How are you feeling?”

“Good, good.” He took another sip of his drink. His face and chest and belly were on fire, and he was just about to sink back onto the mat and let the carver-dentist get started. That’s when he heard it, the distinct sound of small unsteady footsteps hurrying down the hall.

“He’s here!” the old man said, stiffening.

“Excuse me?”

“The boy, the carp-faced boy. Have you seen him yet? You must have seen him. Or are they hiding him from you too? You have to help me.” There was a rush of panic as the old man remembered what he wanted to tell this man.

“It will be all right.” The dentist placed two large hands on Tetsu’s shoulders. Something like a wasp’s sting ignited in his chest. Spread, numbing. He was guided to the floor. One sweeping hand in red, back and forth in front of his eyes. A blur. His eyes too heavy to keep open.

“Ever since,” Grandpa Tetsu said, finding his mouth harder to move. But his hearing remained keen, woosh woosh woosh the robes busied about him. The sweet, clean scent of camphor filled his head. “I poked him when he came too close.”

“You poked him?”

“With the hot end of my pipe.” The old man wanted to explain better, but he was tired, sleepy. He needed to warn the carver-dentist. “He kept coming around, after me. Fish-faced, evil.”

The stranger Nakanishi sat silent, his presence smothering.

“I don’t know where she got him.” The old man’s own voice was too loud in his ears, the words malformed by his softening tongue. “He’s the reason her husband sent her home. Found another woman. A woman who had normal babies.”

“When you’re ready, we can begin.” The dentist’s voice was very near. Three cool fingers touched his cheek.

“The embarrassment,” Grandpa Tetsu said. “You must be careful.” He gave in and opened his mouth, let the spin take him. Plummeting.

Teeth and Truth—

The western sun drove hot into the old man’s back, waking him. He was on his side, a bundle of cloth pushed up under his head. The sticky feel of recent sweat uncomfortable and clammy on his skin. His slow heartbeat a heavy hammer in his temples, in his mouth.

He remembered.

From down the hall he heard the familiar sounds of his wife and daughter in the kitchen, the rhythmic cleaving of a knife through daikon. The gaspy air pumped from the billows into a crackling fire. A giggle and talk he couldn’t quite hear. There was the smell of grilling sea bream, the unmistakable sweetened soy sauce aroma of boiling konbu seaweed. Earthy root vegetables. His stomach growled. A feast, they were preparing a feast? Maybe for him and his new teeth?

With effort the old man opened his eyes, puffy and crusted and nearly sealed shut. The carver-dentist was gone. His bags and bundles and the box had also vanished. The ceramic jar of saké, though, still stood on the table. A squeeze of his hand told him that he continued to hold the tiny cup, it moved in his grip, and he realized he’d probably broken it at some point during the procedure. A shame. It was an expensive cup.

He tried to sit up but there was only more pain. His chest felt bruised as if someone had been kneeling there for a long time. A whimper sounded in his throat. The puddle of drool in his mouth overflowed. Grandpa Tetsu used his swollen tongue to carefully feel for his new teeth, but found his mouth had been packed entirely with wet cloth. He rolled slightly and spit and gagged and pushed the blood-soaked material onto the floor with his tongue.

For a moment he allowed the viscous liquid to drain onto the cloth under his head. Since he couldn’t seem to find the strength to get up, he rolled over onto his back. Some saliva ran down his cheek and filled one ear. His right arm, the one he’d been lying on, had gone completely numb. It was going to hurt like hell in about five minutes.

Grandpa Tetsu’s tongue set out again prodding the places where the broken and cracked teeth had been. But there was nothing. For a second he thought maybe the dentist hadn’t put them in yet. But his tongue slipped all around the inside of his mouth, over the raw, ragged gums, up and down. And he understood.

There was the unsteady patter of feet hurrying down the hall and Grandpa Tetsu tensed. A small hand found its way through a hole in the paper and slung the door open. The toddler came into the room clapping his hands and bending excitedly at the knees.

The old man’s stomach heaved and he turned his head and threw up what little saké he had left in his stomach and quite a bit of blood that he must have swallowed. With much effort, he brought his left hand up to wipe at his inflamed, toothless mouth with the back of his sleeve. It fell heavily across his chest. He wanted to reprimand the child, to yell at him to get out, but he couldn’t find his voice either. This was it, he thought. He’d finally been caught.

The child toddled closer. The old man gripped the broken cup tightly. But something was wrong. He twisted his wrist and opened his hand, craning his neck to look down. He opened his fingers. It wasn’t a cup at all. There he saw the upper and lower plate of false teeth the dentist had shown him earlier. The one with the four teeth pried from a dead crazy Otsubo embedded in the wood.

“Horsey,” the child called and tottered straight past the old man to the open window. There was the faint rustling of long strands of willow, and then in answer, the neighing of a horse, a bray with a very distinctive deeper voice buried underneath. It was telling him something. The carp-faced child laughed and cooed.

So they didn’t sell the horse after all. Why would they sell a creature the child loved so much? Instead they’d paid for the old man’s surgery with his own teeth. His own perfect teeth. And they must have made a small fortune. Enough to have a feast, he thought.

A squeal from the child brought his attention back to the room. Grandpa Tetsu closed his eyes tight. He wouldn’t cry. He never cried. It sounded as if the carp-faced boy had dropped to the mat and had started crawling, slithering actually, closer and closer to the pained and mostly paralyzed man. All he could do was squeeze the fist on his chest, the one with the teeth in it, over and over, and wish for the boy to leave him alone. His eyes screwed shut, he listened as hard as he could. Hot tears escaped his swollen lids.

There came a neighing, the horse’s final rebuke. It seemed to call: I told you so.

The old man heard the pop, pop, pop of a hungry mouth opening and closing, moving closer. And then his right arm suddenly jerked. Again. There was a pulling sensation, a sense of pressure over the tingling that told him the limb was waking up.

Pain.

A smell, yeasty and fetid, enveloped him. Grandpa Tetsu gagged. He tried to scream but only managed a strangled cough. He attempted to roll away from the shooting pain, but something pinned his right elbow to the floor. That’s when he opened his eyes and gazed down.