9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

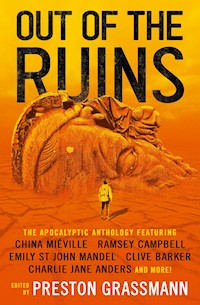

A fresh post-apocalyptic anthology of 18 stories: the end of the world seen through the salvage and ruins. Featuring Emily St John Mandel, Carmen Maria Machado, Clive Barker, China Mièville, Charlie Jane Anders and more. This anthology of post-apocalyptic fiction asks, what would you save from the fire? In the moments when it all comes crashing down, what will we value the most, and how will we save it? Featuring stories from China Miéville, Emily St John Mandel, Clive Barker, Carmen Maria Machado, Charlie Jane Anders, Samuel R. Delaney, Ramsey Campbell, Lavie Tidhar, Kaaron Warrern, Anna Tambour, Nina Allan, Jeffrey Thomas, Paul Di Filippo, Ron Drummond, Nikhil Singh, John Skipp, Autumn Christian, Chris Kelso, Rumi Kaneko, Nick Mamatas and D.R.G. Sugawara.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Cover

Also Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Introduction – Preston Grassmann

The Hour – Clive Barker

The Green Caravanserai – Lavie Tidhar

The Age of Fish, Post-flowers – Anna Tambour

Exurbia – Kaaron Warren

Watching God – China Miéville

A Storm in Kingstown – Nina Allan

As Good As New – Charlie Jane Anders

Reminded – Ramsey Campbell

The Splendor and Misery of Bodies, of Cities – Samuel R. Delany

The Rise and Fall of Whistle-Pig City – Paul Di Filippo

Mr. Thursday – Emily St. John Mandel

The Man You Flee at Parties – Nick Mamatas

Like the Petals of Broken Flowers – Chris Kelso and Preston Grassman

The Endless Fall – Jeffrey Thomas

Dwindling – Ron Drummond

Malware Park – Nikhil Singh

Maeda: The Body Optic – Rumi Kaneko

Inventory – Carmen Maria Machado

How the Monsters Found God – John Skipp and Autumn Christian

The Box Man’s Dream – D.R.G. Sugawara

Acknowledgements

About the author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes

Cursed

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

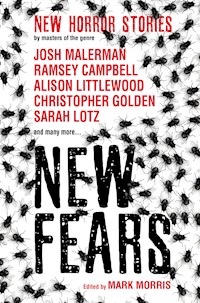

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

When Things Get Dark: Stories Inspired by Shirley Jackson

Wonderland

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

or your preferred retailer.

Print edition ISBN: 9781789097399

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789097405

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Preston Grassmann 2021

‘The Hour’ © Clive Barker 2021

‘The Green Caravanserai’ © Lavie Tidhar 2021

‘The Age of Fish, Post-flowers’ © Anna Tambour 2008. Originally published in Paper Cities: An Anthology of Urban Fantasy, edited by Ekaterina Sedia. Used by permission of the author.

‘Exurbia’ © Kaaron Warren 2021

‘Watching God’ © China Miéville 2015. Originally published in Three Moments of an Explosion: Stories.

Used by permission of Del Rey Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. In the UK, reprinted by permission of Pan Macmillan.

‘A Storm in Kingstown’ © Nina Allan 2021

‘As Good As New’ © Charlie Jane Anders 2014. Originally published at Tor.com, edited by Patrick

Nielson Hayden. Used by permission of the author.

‘Reminded’ © Ramsey Campbell 2021

‘The Splendor and Misery of Bodies, of Cities’ © Samuel R. Delany (excerpt published in 1996 in Review of Contemporary Fiction). Used by permission of the author.

‘The Rise and Fall of Whistle-Pig City’ © Paul Di Filippo 2021

‘Mr. Thursday’ © Emily St. John Mandel 2017. Originally published at Slate. Used by permission of the author via Katherine Fausset at Curtis Brown Ltd.

‘The Man You Flee at Parties’ © Nick Mamatas 2021

‘Like the Petals of Broken Flowers’ © Chris Kelso and Preston Grassman 2021

‘The Endless Fall’ © Jeffrey Thomas 2017. Originally published in the collection The Endless Fall and Other Weird Fictions, Lovecraft eZine Press. Used by permission of the author.

‘Dwindling’ © Ron Drummond 2021

‘Malware Park’ © Nikhil Singh 2021

‘Maeda: The Body Optic © Rumi Kaneko 2021 ‘Inventory’ © Carmen Maria Machado 2018. As published in Her Body and Other Parties: Stories. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org. In the UK, reprinted by permission of Angelika

Palmer at Profile Books.

‘How the Monsters Found God’ © John Skipp and Autumn Christian 2021

‘The Box Man’s Dream’ © D.R.G. Sugawara 2021

Interior art © Yoshika Nagata 2020

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Preston Grassmann

MY earliest memory of a literary apocalypse was discovered in the remainder bins of a local bookstore. The Ruins of Earth (edited by Thomas M. Disch), with its emblematic cover of an egg-shaped world about to crack open, contained stories of ecological catastrophes and end-time scenarios that were so impressionable to my young mind, it might’ve been me emerging from that shell. But it was one story, in particular, that has remained with me through the years—“Cage of Sand” by J.G. Ballard. In that quintessential narrative, Ballard describes an abandoned Cape Canaveral inhabited by drifters of a lost space-age, where “the old launching gantries and landing ramps reared up into the sky like derelict pieces of giant sculpture.” That might’ve been the first time, in those early golden-age years, that I realized that some kind of beauty can be salvaged from the relics of the past. I went on from there to read The Drowned World, High Rise, and Concrete Island before I found my way to other writers who could sing among the ruins—many of them are in this book.

In more recent years, I had the opportunity to attend an exhibition at London’s Tate gallery called “Ruin Lust,” (derived from the German word Ruinenelust). It was filled with images of decaying structures, pieces of castle walls, the remnants of ghost-towns and demolished buildings. I remember feeling a mix of dismay and nostalgia at first, but that soon gave way to that same sense of excitement that I’d felt when reading Ballard. Here was proof that whatever falls apart in our world can be turned into something new. The surreal photographs of Paul Nash or the abandoned-London images of Jon Savage were about reimagining the world in the wake of destruction, not reveling in its end. They were about finding a way out, of transforming those Ballardian gantries and landing ramps into something of value. During that exhibition, I realized just how much scenes of ruin can traverse the present moment, pointing back in time while offering a glimpse of tomorrow—one where salvage and survival was (and is) possible.

It wasn’t that long ago that public health officials announced an event that felt (and still feels) like a harbinger of the end times. We’ve lived through a global crisis that has taken lives, stalled world economies, and altered our sense of reality in ways that none of us could foresee. For many of us, this continues to be an apocalyptic moment; a cataclysm that can both ruin and leave ruins in its wake. But as is true with all the cataclysms of history, we survive through our creations, salvaging the remains of our past to build something new. On a societal level, we can raise new cities and systems of belief. As individuals, we can rise out of our own private ruins; the versions of ourselves that survive. In this, a single poem or a story (or a photograph in the Tate gallery) can be as revealing as a city.

The idea of apocalypse as an end-of-the-world event is a modern conception. The ancient Greek word, apokalypsis, was about revelation and disclosure, uncovering what was once concealed. In Middle English, it referred to insight and vision or hallucinations. The word itself, if you’ll pardon the indulgence, has emerged from the ruins of its previous definitions, while holding on to some part of its origins. As you’ll see from the stories that follow, all of its potential meanings have been salvaged. In China Miéville’s “Watching God” or Kaaron Warren’s “Exurbia,” the survivors uncover their truths in the ways they’ve adapted to the ruins they inhabit. Others offer their end-of-the-world insights with levity, as in Paul Di Filippo’s “The Rise and Fall of Whistle-pig City” and Charlie Jane Anders’s “As Good As New.” In stories like Emily St. John Mandel’s “Mr. Thursday” and Ron Drummond’s “Dwindling,” the ruins can be a verb, where the scale of revelation comes down to the lives of individuals—the ways in which they emerge from the wreckage of their private histories. In John Skipp and Autumn Christian’s “How the Monsters Found God,” or Nina Allan’s “Storm in Kingstown,” hope is what remains, the revelation we take away. But all of the stories that follow have their apokalypsis, with unique visions of what worlds can be or what they might become. And no matter how dark they are, they also acknowledge that each of us can excavate something of value from the ash of our end times and make something new.

Great things can be born Out of the Ruins.

by Clive Barker

The Hour! The Hour! Upon the Hour!

The Munkee spits and thickets cower,

And what has become of the Old Man’s power

But tears and trepidation?

The Hour! The Hour! Upon the Hour!

Mother’s mad and the milk’s gone sour,

But yesterday I found a flower

That sang Annunciation.

And when the Hours become Day,

And all the Days have passed away,

Will we not see—yes, you and me—

How sweet and bright the light will be

That comes of our Creation?

Lavie Tidhar

EVERY winter around January the Green Caravanserais began to make an appearance around the Ghost Coast between Taba and Nuweiba. They were slow moving, patient and cautious—as well they should be, Saleh thought. For the paths they traversed were hard and the Ghost Coast itself could be deadly.

Saleh crouched on top of the unfinished castellated tower of what had once been, or could have been, a grand hotel. He could look out for miles. The Red Sea sparkled to the east, with the Saudi mountains rising behind on the shores on the other side of the gulf. The outlines of empty swimming pools dotted the landscape of heavily built, abandoned buildings each grander than the rest—

Bavarian Romanesque castles jostled against basilicas built in faux-Gaudí style, which in turn nestled against miniature Egyptian pyramids. Moorish arches vied with Doric columns next to a vintage American diner and an extensive garden, maintained by rusty, salvaged robots, was set up like a budget Alhambra.

Here and there Saleh could see craters of the ancient wars, where nothing lived and no one had settled, and fresh holes which a giant sandworm—the Vermes Arenae Sinaitici Gigantes were another relic of the war—might have dug. This strip of endless hospitality architecture ran all the way from the ancient border with what was now the entwined dual polity of the digitally federated Judea-Palestina Union to Sharm El-Sheikh, near the tip of the peninsula.

Beyond it lay the desert, eternal and hostile to humans as it always was.

It was from the desert that the Green Caravanserai came. Saleh, eyes bright, watched the distant, slow procession. The goats came first, a brown and white herd treading with an easy gait. Robed figures moved between them. Then, behind them, came the elephants.

There were several elephant families in the herd. Saleh watched enraptured, for he had always loved elephants. These were sand-coloured from the long march, and they moved with a kind of majestic unhurriedness, unencumbered by humans, seemingly indifferent to the elements. They were desert elephants, and in a lifetime could make the slow back-and-forth crossing many times. Moving between them were more humans, robed and with traditional keffiyehs covering their heads. Small robots and drones crawled and hovered and slithered in between.

And now Saleh could see solar gliders rising overhead on the hot winds.

Behind the elephants came the first of the caravanserai proper, though in the idiom of the travellers it was still called by its old name of a khan. Saleh watched as the building slinkied itself across the sands. The old caravanserais or khans were rest stops for the merchant trains along the silk and perfume roads. Now the Green Caravanserai brought their own buildings with them, semi-sentient machines that could build and rebuild themselves with ease and adapt to their surroundings, drawing energy from wind and sun.

Camels came behind the khan and hordes of children, horses, wagons pulled by snail-like robots until the whole thing resembled less a caravan than a carnival.

Saleh always looked forward to the caravanserais’ arrival each year, though until now he had never gone near one, for his father was always the one to represent the tribe at the trade meeting, and Saleh was not allowed to come.

But not this time, he thought. This time he had his own thing to trade, paid for in blood and despair.

His father was gone.

No. This time he, Saleh, would go. This time he would meet the elephants.

He watched as the Green Caravanserai reached just beyond the old coastal road that bisected the Ghost Coast from the desert. There they stopped, in successive waves. The khans reassembled and formed into simple, solid shapes that looked a little like round beehives. The small robots formed a fence and the people of the caravanserai laid down solar sheeting and set up atmospheric water generators. The kids played with the elephants. The goats chewed on the bark of trees.

Saleh abandoned the castellated tower of the old hotel. He slid down stairwells and in and out of windows. It was not protocol to go alone. The Abu-Ala foraged the Ghost Coast for old machines and they had long ago made arrangements with the caravaners, so Salah would be going against both tribe wishes and simple decorum.

He paused in the entrance of the old hotel. The sun beat down. The Ghost Coast—this endless strip of vintage neo-kitsch architecture suspended in time and gently falling apart—spread away from him.

He stared at the road then, almost unwillingly it felt to him, he began to march towards the Green Caravanserai.

* * *

Elias scratched hair out of his eyes and looked with curiosity at the boy striding nervously across the road. The boy had no way of knowing this, but right then he had the attention of several heavily armed drones, a detachment of caravaner rangers and of old Umm Kulthum, the matriarch of the elephant herd herself, and if he set one foot wrong or drew any kind of weapon or if he just sneezed, really, he’d turn into hot desert dust long before his brain could even process the idea.

Which would be a shame, really, Elias thought, because the boy seemed nice, if rather nervous.

This really wasn’t protocol.

The thing about the Sinai was that, beyond the stretch of the Ghost Coast, and after centuries of sporadic warfare, nothing in the desert was particularly safe. It was littered with old mines, traps, unexploded ordnances, mutated bio-weapons and sentient machines that no one even remembered designing in the first place. The only people to cross it were the caravaners, who went in search of old military tech that had resale value, and to get through it time and time again they had become proficient in the art of not dying.

They were not specialists in the tech: it was people like the Abu-Ala tribe of the Al-Tirabin, for example—who foraged the Ghost Coast—that collected the stuff. The caravaners just haggled for it, then carried it back across the mountains and wadis and the desert, ranging from Cairo in the west to the glittering sprawl—Al-Imtidad—of Neom in the east and sometimes even to Djibouti in the south.

Elias watched as the boy crossed the road. Elias was mounted on top of the now-stationary khan, and he’d been observing the boy for quite a while now, ever since his heat signature was detected on top of a tower in the dense network of abandoned buildings that made up the coast.

Long ago, the coast was a busy hive of activity as tourists came from all over the world, from Israel and Russia and the European mass and that big island just off Europe the name of which Elias could never remember, but was an important polity for a short time back in the sometime or other. But then the tourists stopped coming, the ever more lavish hotel and resort buildings were never completed, and then the wars came, and with them the Leviathans that still haunted the depths of the Red Sea, and the Rocs that snatched the unwary and carried them to nests high up in the mountains and laid their larval eggs in them, and the sandworms—and whose stupid idea was that one? —that still bred and grew enormous in the sands.

There was other movement in the area—one sandworm lay dormant two clicks away and deep underground, and a group of non-sentient but mobile unexploded ordnances was gathered in what looked like a Roman villa four clicks back towards Taba, but surprisingly there were no humans and no Abu-Ala as one would usually expect to find.

None, that is, but for the boy.

Elias shrugged, put the goggles back on so he could continue monitoring the immediate area, jumped out of the khan’s top deck and slid smoothly down one of the now-tentacular bases.

The boy crossed the road and came to the perimeter of the caravanserai and stopped.

Elias came and met him.

They looked at each other curiously.

“Hello?” the boy said, uncertainly.

“Yes?” Elias said. He knew it was unhelpful. But there were protocols in place. And this wasn’t it.

“I am Saleh,” the boy said.

“Yes,” Elias said, dubiously.

They stared at each other.

* * *

Saleh wasn’t going to let them intimidate him. Even though he was intimidated. Badly. Two tiny crawling robots came over the line and examined him with extended feelers.

The other boy said, “Try not to move.”

Saleh stood very still. He took a deep breath. He said, “My name is Saleh Mohammed Ishak Abu-Ala Al-Tirabin.”

At this the other boy looked more interested. “You are an Abu-Ala?”

“Yes.”

“You are not the designated contact,” the boy said.

“No.”

“So why are you here?”

Saleh was sweating, though the air was chilly. He said, “I have something.”

“So?”

“Something to trade.”

The boy looked interested again. “Is it valuable?” he said.

“I think so.”

The boy seemed to consider. “Still,” he said. “We deal with the tribe, not with individual scavengers. It makes everything easier. Safe.”

Saleh said, “There is only me.”

“Excuse me?”

Saleh swallowed.

“There is only me,” he said quietly.

And then he started to cry.

* * *

Saleh sat miserably on the mat while Elias brewed sage tea. Elias had had to bring him in, hadn’t he. The boy was no longer deemed a threat. Saleh accepted the tea gratefully. Elias brought out pistachios and hard biscuits. He set them on a plate and sat cross-legged across from Saleh.

“What happened to them?” he said. He tried to speak gently.

Saleh shrugged.

“We were excavating in Dahab,” he said. “It used to be a robotnik nest during the second, no, maybe the third war. You must have seen the satellite pictures of Dahab, right? It had a terrorartist attack in the fourth war and the whole place is suspended in a sort of still-ongoing explosion, but if you wear a null suit you can navigate through the temporality maze—anyway. We were digging. Dahab’s full of valuable old stuff, it’s just hard to get. Then, something… broke loose.” He blinked. “I don’t know what. A ghost.”

“A ghost?” Elias said.

Saleh shrugged again, helplessly. “One of the old Israeli robotniks, I think. It was still alive somehow, inside the explosion. Most power sources don’t work inside the terrorartist installation so we bring in portable fusion generators when we go in. I think my dad brushed too close to the old robotnik and somehow it drew power from the generator and—and it came alive. They were cyborgs, with biological brains but mostly machine otherwise. I don’t even know if it was alive in a real sense, only responding to what it saw as battle. So it came loose and it killed my father and the rest of… It killed everyone.”

“I am sorry,” Elias said. He looked at the boy in front of him. Two years back they had lost Manmour, the elephant, to tiny mechanical spider things that had swarmed out of one of the wadis. Only the skeleton remained and then the machines vanished again, and what they did with Manmour’s skin and flesh and blood nobody knew. The elephants grieved and the whole caravanserai grieved with them.

“Drink your tea,” Elias said compassionately.

* * *

Saleh closed his eyes. The teacup felt warm between his hands.

“Everyone else was away,” he said quietly. He had to get the words out. Had to tell Elias what happened. In a way it was a relief.

“Most of the tribe’s down in Sharm or St. Catherine’s. But I got it, you see.” He opened his eyes and stared at the other boy, this Elias, with his strange goggles and short-cropped hair and curious, interested gaze.

“You got it? What?” the boy said.

“The thing we were looking for.” Excitement quickened in him then. “My grandfather Ishak and my father, Mohammed, they kept looking. Even though it was dangerous. Even though it was hard. Every year the terrorartist bubble moves outwards just a little. It is still alive, the explosion still happening. You know much about terrorart?”

“A little. Rohini started it, didn’t they? The Jakarta Event.”

“Time-dilation bombs,” Saleh said. “Yes, Rohini. There were others. Mad Rucker who seeded the Boppers on Titan. Sandoval, who made the installation called Earthrise out of stolen minds on the moon. There were never many, thankfully. And they were mass murderers, every one. But the art, I know people are interested in it.”

“There are collectors,” Elias said. “Museums, too. What did you find?”

“This,” Saleh said, simply. He opened his bag and took out a small metal ball. It felt so light. “It’s the time-dilation bomb.”

Silent alarms must have gone off somewhere, because a moment later he had caravaners and drones both surround him. He never even heard them coming.

Elias let out a slow exhalation of breath.

“And how did we miss that?” he said.

“It’s empty,” Saleh said. “The explosion, Dahab, everything? It’s still going on. My father, my uncle, they’re still inside it. An endless death, still happening. The robotnik pulled them into the field. Only I got out.”

He didn’t dare move. The weapons were on him. Elias said, “May I see it?”

“Of course.”

Saleh gave it to the other boy.

* * *

Numbers danced behind Elias’s goggles. He nodded and the weapons around Saleh relaxed, if only a little.

Elias said, “It’s genuine. That’s a real find.”

Defiance in the other boy’s eyes. “I told you.”

“You speak for your tribe?” Elias said.

“I speak for myself.”

“And the Abu-Ala? Where do the rest of your people stand on this?” Elias said.

Saleh shook his head. Carefully. “This is mine,” he said. “It is all that is left. The others will appoint a new speaker in time.”

“What do you want for this?”

“I want enough,” Saleh said. He seemed desperate. “It’s priceless, an original terrorartist artefact.”

“That it is.” Elias turned it over in his hands. It felt so light. He said, “What do you need the money for?”

Saleh said, “There is nothing for me here. I want to go away. Far away. I thought… I could travel up the ’stalk to Gateway, get a ship out.”

“Mars? The moon?”

“Titan. I always wanted to see Titan.”

Elias felt sorry for him. “You can’t run away,” he said, as gently as he could. “Even in space, you’d still just be yourself. And lonelier than you could ever imagine.”

“Maybe. But I have to get out.”

“I’m sorry,” Elias said. And he really was. But this was business.

He said, “It’s rare. It’s valuable. There’s no question about it. But it’s just an empty bomb husk. Even with provenance. You’d have to find the right collector, and even then… it won’t get you to Mars. It would barely get you a one-way ticket on the ’stalk. We would buy it off you, of course. But we are wholesalers, not collectors. I can’t offer you what you want and, even if you could somehow sell it at full price somewhere else, it won’t be as much as you’d hope.”

He saw the light die in Saleh’s eyes. Saw it, and felt terrible.

“My father, my uncle, my cousins, everyone…”

“Yes,” Elias said.

“All for nothing,” Saleh said.

“Not nothing,” Elias said.

* * *

Saleh barely heard him. He stared at that awful, empty husk. So many lives. And so many still caught in that outwardly expanding explosion, the final installation of a mad artist who took delight in destruction and death.

He could go back, he thought. Go find the rest of the Abu-Ala, follow the coast to Sharm.

He didn’t want to, he realised. Even before it all happened, he did not want to live his life this way. Scavenging old tech in the crumbling, rotting, endless maze of architecture on the Ghost Coast. Marrying, and having a family, so one day he’d have a son, so one day his name would pass on along with the tribe’s.

He wanted to see Al-Imtidad, he realised. He wanted to see the glitterball underwater cities of the Drift, the view of Earth as seen from the observation decks of Gateway, high in orbit. He wanted the moon. He wanted Mars.

Instead he was here.

He couldn’t, wouldn’t go back, he thought. He shook his head. He blinked back tears.

“Thank you,” he said, formally. He took back the find. The bomb. “I will find a buyer. I will go—”

“How will you go?” Elias said, ruthlessly.

Saleh felt trapped. “I will go,” he said. “I will find a way.”

“You could come with us.”

Saleh looked at Elias. The other boy was smiling.

“You could be useful,” Elias said. “And we can always use a steady set of hands.” He tapped his goggles, which must have connected him with the rest of the caravaners, Saleh realised. “It is already decided by quorum. If you would like to, that is.”

“Where do you go?” Saleh said.

Elias shrugged. “Along the coast, still, for a while. Then back through the desert before the summer comes. Perhaps to Bahrain.”

“Where the Emir of Restoring and Balancing sits on its throne?” Saleh had dreamed of visiting that island, too.

“There is a market there for antiques among both digitals and humans,” Elias told him. “You will come?”

“I…”

* * *

Elias removed his goggles. For a moment the world seemed lesser, disconnected. Then it resolved into its true shape and he saw Saleh as he really was, small, human, afraid.

He extended his hand to the other boy.

“Yes,” Saleh said. His hand was warm in Elias’s grip.

“Good,” Elias said simply. They rose together from the woven mat.

“Tell me,” Elias said, smiling. “Have you ever met an elephant?”

Saleh shook his head. He was smiling, too. “Then let me take you,” Elias said. “They’d love to meet you, you know.”

And together, the two boys left the khan, hand in hand, and wandered off into the enclave of the Green Caravanserai, where a herd of elephant were playing in the mud.

Anna Tambour

1.

JUST when you think you’ve killed them all, others impossibly wriggle over the wall. Or bore through it, some say. Or worse—though this might be another rumor—breed within.

As for the sounds, there’s lots of speculation, some of it pretty noisy itself. Are the sounds some new tactic to get rid of the orms? We in the corps have argued about that, most of us too scared to want to talk about it, or to want to hear it discussed; but (and it could be a pose) a few loudmouths insist on spouting daily assurances that the Sound, as they say it Capitalizedly, is the Newest Advance in our age. This might be convincing if they, the optimists, weren’t doing the mole act along with the rest of us, and running downstairs as fast as they can when the first sounds rumble in the distance every forsaken morning. They answer collateral damage, possible risks, someone will tell us, never you mind and the sun will come up sunny one day.

Today we got another report closer to home. An orm, a relative baby though thick as a man’s thigh, its dorsal fin tall as his waist, and its mane thick and coarse as cables. Just a block away, it was caught in the act of engorgement, two legs waving from its maw.

The story goes that a man in blue shot it with his harp-net. The orm’s tail wasn’t properly caught, and smashed the guy’s stomach to pulp, but the mib had already called the orm squad. The person in the orm (unknown sex) was already a lost cause. That orm would feed a hundred New Yorkers, maybe plenty more from outside. That’s what Julio says because he saw someone who saw the squad load it into their omni. All just speculation on my part. I’m not a knower, and I don’t know anyone who is.

The sounds and craters are something else. The sounds come always at dawn. In them are elements of rumble, drag, shear, and I would imagine earthquake, all in one indefinability, just the sound to make you wake shaking from a dream, though this isn’t one. Correction: wasn’t one before. The real has exceeded dreams—former dreams, that is.

The sounds have patterned our waking. We all run down to the drypit (though none of us has slept enough) and huddle there feeling the building tremble (or is it just us?) till the day calms, relatively.

* * *

It’s still raining. We passed the forty days and forty nights mark long ago, thankfully longer ago than anyone in our corps cares to harp about. No one left amongst us is the quoting type. I don’t remember the last time the moon shone.

Two levels of underground car park in our building are now nicely filled with water. So we don’t have that to worry about. Power could have been a problem but for our resident genius, an arrogant creep otherwise. Julio is the only person who can relate to the guy, but as long as Julio stays with us, we’re laughing. (Must keep Julio happy!)

Julio is a genius, too, but a different kind. He named us “The Indefatigables” but that is really he. He found it in a book, he says, in his self-effacing way, but he is the one. I have never been able to figure him out. I thought perhaps it was love, and of who else but Angela Tux? But she left almost at the beginning and Julio stays. He says we give him purpose and that he loves the Brevant, and maybe we do and he does. I certainly must give him purpose, as I don’t think I could live without what he’s done for us.

The Indefatigables, properly the coop of the Brevant Building, “the corps” as we call ourselves, would be happy as clams these days (no irony intended) if we could only get more dirt. George Maxwell goes out for it instead of just wishing we had more. He went all the way to 51st Street yesterday to find a dirtboy with real dirt.

He was so upset he didn’t mind the danger, he said. I think that he was so upset he didn’t think of the danger. I’ve never sought a dirtboy. Too frightened of being killed for my seeds. George, though, is a big guy, played varsity in Yale (people say it’s still around, where the knowers are). George is one of those guys whose muscles get more tough with age as does their stubbornness. We’ve got quite a collection here now in our little group, none as brave as George or useful as Julio, but we like to say each has something to offer. The building used to be filled with useless types—hysterical, catatonically morose, or verbally reminiscent—but they died out or disappeared. I’m proud and, I admit, lucky to be part of our corps now.

From Julio, the super, we hear rumors. He was the one who told us to fortify, though in the end, it was only him and George Maxwell who stuck broken glass and angle-edged picture frames and sharpened steel furniture bones into the outside wall, one man sticking, the other man guarding the sticker with a pitiful arsenal of sharpened steel. For the steel, it surprised us all how many of us had Van der Rohe chairs. I got mine at a ridiculously cheap price from a place in Trenton, though the delivery, by the time they were all installed in my apartment (I had to get three at the price), was ridiculous. I was glad to donate the chairs. They had always seemed to unwelcome my sitting in them, and gloat when I left them alone. Until the defenses project, I had never been able to part with them, but the prospect of them being torn asunder into ugly scrap gave me the best day I could remember in this age.