Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

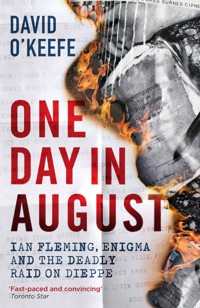

'A lively and readable account' Spectator 'A fine book ... well-written and well-researched' Washington Times In less than six hours in August 1942, nearly 1,000 British, Canadian and American commandos died in the French port of Dieppe in an operation that for decades seemed to have no real purpose. Was it a dry-run for D-Day, or perhaps a gesture by the Allies to placate Stalin's impatience for a second front in the west? Historian David O'Keefe uses hitherto classified intelligence archives to prove that this catastrophic and apparently futile raid was in fact a mission, set up by Ian Fleming of British Naval Intelligence as part of a 'pinch' policy designed to capture material relating to the four-rotor Enigma Machine that would permit codebreakers like Alan Turing at Bletchley Park to turn the tide of the Second World War. 'A fast-paced and convincing book ... that clears up decades of misinformation about the ignoble raid' Toronto Star

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 850

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

Praise for One Day in August

NATIONAL BESTSELLER

Finalist for the RBC Charles Taylor Prize

Finalist for the John W. Dafoe Book Prize

Finalist for the Canadian Authors Association Literary Award

A Globe and Mail Best Book

‘A fast-paced and convincing book, One Day in August … clears up decades of misinformation about the ignoble raid and should provide comfort for the few remaining survivors of that notorious massacre … Building on the work of previous historians who didn’t have access to the documents he had, O’Keefe has provided meaning to what has always been seen as a senseless massacre. And for Ron Beal, who witnessed the slaughter 71 years ago as a bewildered and terrified private, that is everything. “Now I can die in peace,” he told O’Keefe. “Now I know what my friends died for.” Amen to that.’

—Toronto Star

‘Based on extensive original research … O’Keefe’s landmark new book presents a new and original explanation of what happened on that fateful August day in 1942.’

—The Globe and Mail (Best Book)

‘This is a valuable, well-researched, and thought provoking book. The author has uncovered new evidence and cleared up a lot of questions … I have known for years that there was an intelligence-gathering element in the plan; but not to the extent revealed by David O’Keefe. O’Keefe’s book is a must read if one is to really understand the Dieppe raid.’

—Julian Thompson

‘Highly original and bracingly revisionist, One Day in August is that rare book that is able to say something new about something so familiar. Based on extensive research in official records in Canada and Britain, many of iithem previously undiscovered or long-forgotten, One Day in August is historical writing at its best: engrossing, revealing, and enlightening.’

—Citation, RBC Taylor Prize

‘O’Keefe has definitely made the biggest breakthrough of the last twenty years in our understanding of the raid … His principal research achievement is to have kept digging in the British archives with such persistence that the keepers of the British code-breaking secrets conceded that there was no point holding back the remaining records linking Bletchley Park, Ian Fleming and the Dieppe raid.’

—Peter Henshaw, Dieppe scholar and intelligence analyst, Privy Council Office

‘In the same way that intelligence in the Second World War had to be based on multiple sources rather than a single thunderclap moment or dramatic source, David has built this case through a whole series of small pieces of evidence … [He] has certainly changed our view of Dieppe into the future; he has added a new dimension that we really weren’t aware of before.’

—Stephen Prince, Head, Naval Historical Branch, Royal Navy

‘The most important work on the [Dieppe] raid since it occurred in 1942.’

—Rocky Mountain Outlook

‘O’Keefe tells a masterful story of the intrigue and cryptology behind the fighting forces … I will be among the first to say that any subsequent book on Dieppe or Ultra intelligence will have to take into account his stunning new research and bold claims … For years, popular histories were derided, especially by academics, as all story and no analysis, and for offering few new contributions to understanding the past. But that seems to be changing in recent years, as the best popularizers find new hooks and angles for their histories, and employ new evidence – usually oral histories, or, in O’Keefe’s case, deep archival research – in innovative and revealing ways.’

—The Globe and Mail

v

Contents

About the author

Professor David O’Keefe, a former officer in the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment of Canada), is an award-winning historian, author, film-maker and leading authority on Canadian military historical research. He currently teaches history at Marianopolis College in Quebec.

List of Illustrations

Maps

England and France, 1942

Operations Anklet and Archery

Movement across the Channel to Dieppe

Operation Jubilee: August 19, 1942

Targets in Dieppe harbour

05:20. Infantry and tanks land on beaches and destroy road blocks

Approx. 06:00. HMS Locust enters the inner channel (the ‘Gauntlet’)

06:10–06:40. Royal Marine Commandos and IAU obtain intelligence booty

06:30–07:00. IAU depart Dieppe with intelligence booty

Plate section

1. Private Ron Beal, 2012

2. Ian Fleming in naval uniform

3. Rear Admiral John Godfrey

4. Admiral Karl Dönitz

5. The naval four-rotor Enigma machine

6. The ‘Morrison Wall’ at Bletchley Park

7. Two sets of spare rotor wheels for the Enigma machine

8. Three Enigma rotor wheels laid out on their sides

9. Frank Birchxii

10. Alan Turing

11. A captured Enigma wheel

12. Harry Hinsley, Sir Edward Travis and John Tiltman

13. Major General Hamilton Roberts

14. Captain Peter Huntington-Whiteley

15. No. 10 Platoon of X Company, Royal Marines

16. Captain John ‘Jock’ Hughes-Hallett

17. R.E.D. ‘Red’ Ryder

18. An aerial reconnaissance photo of Dieppe harbour

19. One of the earliest known maps for the Dieppe Raid

20. The entrance to Dieppe harbour

21. Trawlers in Dieppe harbour

22. An RAF aerial photograph of the Dieppe harbour mole

23. A further part of the Dieppe defences

24. HMS Locust

25. The aftermath of the fighting on Red Beach

26. An RAF aerial photo of the Dieppe Raid in progress

27. German propaganda photo of the carnage on Blue Beach

28. A photo included in an American report on the M4 cipher

29. The survivors of No. 10 Platoon in Operation Torch

30. Paul McGrath with No. 10 Platoon in 1945

31. Private Ron Beal of the Royal Regiment of Canada

xiii

For those like Ron Beal who never knew; and for those like Paul McGrath who did.

xiv

Note on Sources

An Ode to C.P. Stacey

‘No respectable historian would dream of writing a Naval history of the late war unless he was given access to our sources of information,’ mused John Godfrey at the end of the Second World War. His successor as Director of Naval Intelligence, Rear Admiral Edmund Rushbrooke, elaborated on the system adopted in the United Kingdom. ‘The Head of the Historical Section (Royal Navy) had been indoctrinated into Special Intelligence,’ he wrote, and ‘it may be found necessary to indoctrinate others of the Historical Staff, such as the writer of any history of the U-Boat Campaign which was influenced in a dominating way by Special Intelligence.’

The British realized that skilled historians would question the multitude of inconsistencies, open-ended questions and all-encompassing excuses for various events – including Dieppe. Fearing that their curiosity would lead to unintended revelation of the source – one that continued to be used in the Cold War – both the British and the Americans adopted a hybrid approach: historians would be indoctrinated into Ultra, but the use of the material would be severely restricted. Official army, navy and air force historians were then instructed to use this knowledge to sidestep any historically dangerous areas – a process xvisimilar to the way the Admiralty used Ultra to reroute convoys from the clutches of U-boat wolf packs. This privilege was not made available to the official historians in Canada, although Canadians took part in Ultra-inspired missions, worked at Bletchley Park, and were indoctrinated in and used the material in the field.

When the brilliant patriarch of Canadian military history, Colonel Charles P. Stacey, set his official historical team to work on Dieppe in the days following the raid, he was fighting a historical battle with one hand tied behind his back. The story line fed to the war correspondents to protect the true intent of the raid spilled over into the historical realm, creating an impenetrable fog. Forced to rely on the personal testimonies of men sworn to secrecy to lay the cornerstone for our understanding of the raid – sanitized after-action reports, official communiqués, war diaries and snippets of message logs – Stacey lacked the essential ingredients and contextual knowledge to achieve a firm understanding of Dieppe. But Stacey was no fool: as the war went on, he realized that the Allies did have something up their sleeve, but he had no clue at that time about the nature of Ultra, how pervasive it was, how it was used, or the sources and methods used to maintain the flow. Regardless, he was able to cobble together a truly accurate ‘human’ account of the battle – one that will never fade from history.

After the revelation of Ultra in the late 1970s, the initial expectation that it would rewrite the history of the Second World War soon faded as the British government released only a tiny portion of the millions of pages of material created under that security stamp during and after the war. On the fiftieth anniversary of the war’s end, in 1995, both the British and the American governments embarked on a protracted release of these documents, which continues to this day. Although I began my research that same year, the story has emerged slowly and I did not have a single ‘eureka’ moment as such, but rather a string of significant and exciting finds, and countless hours of dead ends, that in the end allowed the pieces of the puzzle to fall into place. It was the painstaking assembly of minuscule pieces of evidence – balanced, sorted and weighed against other evidence – that has finally allowed me to tell the ‘untold’ story of Dieppe. New technologies such as the internet, the microchip and digitization – ones that would have xviidelighted Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, Frank Birch and Ian Fleming – have allowed me to consult more than 150,000 pages of documents from archives on two continents and over 50,000 pages of published primary and secondary source material for this book.

The methodology I employ is straightforward, based in large part on the sage advice of a multitude of mentors in the historical realm and, perhaps rather ironically, on the musings of Colonel Peter Wright, the man who served as General Ham Roberts’s intelligence officer aboard the Calpe. After the Dieppe fiasco, Wright went on to become the highly respected and Ultra-indoctrinated intelligence master for General Harry Crerar’s First Canadian Army throughout the battles in Normandy and north-west Europe. On his return from the war, he resumed his legal practice and was eventually appointed a judge on the Ontario High Court of Justice. He believed that the primary job of the intelligence officer is first to assess what the enemy is doing and then what he should be doing – sage advice I adopted as my general approach to historical inquiry. In other words, the evidence must drive the story. In this case, because there is much ‘white noise’ surrounding the Dieppe saga, I placed greater weight on the documents created before or during the raid than on those written later. Because the Dieppe scholarship is vast, much of this material had to be left on the ‘cutting-room floor,’ though I used it during my research phase to eliminate possibilities, myths and conjecture, and to provide a litmus test for my analysis.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, one historical commentator proclaimed that nothing more could be said about this war and that it was time to move on to the history of the Cold War. The remarkable revelations in this account are but one example of the short-sighted nature of that comment. As long-classified materials on Ultra and on other conflicts make their way into open archives around the world, we realize that the book never closes on history and that only now can the real history of the Second World War begin to be written.

I have decided to adopt a hybrid approach to writing this treatment, and I employ an unfolding narrative as the vehicle to deliver the goods. Unlike strict academic studies where one can simply read xviiithe introduction and conclusion to get the main points down, I have decided to peel the layers back chapter by chapter not only to inform and enlighten but hopefully to captivate the reader with the truly miraculous world of historical investigation. Likewise, explanations and qualifications of evidence considered too detailed for the main narrative are dutifully tucked away in the endnotes to satisfy and amplify traditional scholarly demands. As such, One Day in August unfolds page by page, like a grand mystery that requires it be read from cover to cover for full historical impact and enjoyment.

Although this new interpretation answers many of the old questions surrounding the intent behind the Dieppe Raid, it also raises a slate of new ones that organically emerge as a direct result of the evidence unearthed and the constantly evolving nature of historical understanding. Essentially, it provides a firm foundation from which to build a more complete picture of the Dieppe Raid and the reasons behind it. In the coming years, more information will undoubtedly grace the vast wealth already available. The various agencies responsible for SIGINT material – the Government Communications Headquarters in England, the National Security Agency in the United States and, to a lesser extent, the Communications Security Establishment Canada – along with the respective arms of the ministries or departments of defence – continue to release documents into the public domain year after year.

Like the generations of skilled historians who passed the torch to me many years ago, I turn this interpretation of Dieppe over to a new generation of young scholars. I hope they will be as inspired as I have been to dive into the realm of historical research – regardless of the subject or the challenge. xix

xx

Prologue

August 19, 1942, 0347 hours, English Channel off Dieppe, Normandy, France

Moving swiftly across the slick deck of the drab grey British destroyer HMS Fernie and up onto the bridge, a peacoat-clad Royal Naval Voluntary Reserve officer from Special Branch discarded his hand-rolled cigarette and pressed his binoculars to his eyes, adjusting the focus wheel to account for the darkness. In the distance, a series of fire-red mushroom-shaped explosions merged with the silver glow of bursting star shells and a carnival of red, orange and green tracer fire that darted back and forth just above the ink-black waterline. Then came the echo of staccato machine-gun and high-powered cannon fire, punctuated at irregular intervals by the whiplash crack of larger-calibre naval gunfire.

Straining to discern friend from foe, Commander Ian Fleming stood among a group of Allied journalists, broadcasters and photographers and American military observers expecting to witness the successful execution of the largest amphibious raid of the war to date, known as Operation Jubilee. But it was now clear to all aboard that something had gone wrong, and that the carefully synchronized raid, planned by Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Headquarters and involving a largely Canadian force, had begun 63 minutes prematurely. 2

Ian Fleming – who a decade later would write Casino Royale and launch his immortal James Bond dynasty – was listed innocuously on the ship’s manifest that day as a ‘guest.’ For years, historians and biographers have asserted that the normally desk-bound member of the British Naval Intelligence Division played no role other than that of observer, and that Fleming’s natural desire for action and adventure, fused with an innate talent for bureaucratic machination, had landed him a prize seat on the Fernie, the back-up command ship.

But this ‘guest’ was in fact present in an official capacity – to oversee a critical intelligence portfolio, one of many he handled as personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence, Rear Admiral John Godfrey. He was on board to witness the launch of a highly specialized commando unit that had been created specifically to carry out skilled and dangerous operations deemed of the greatest urgency and importance to the war effort. Fleming’s crack commando unit was set to make its debut under cover of this landmark raid on the coast of German-occupied France.

With the dawn, however, came the sober realization that the raid had gone off the rails in truly epic fashion. As the sky lightened, Fleming could see heavy German fire coming from the hotels that lined the beachfront and ribbons of flame flaring out from the towering clifftops. Below, the main beach – which had hosted generations of English vacationers, including Fleming himself, who had won and lost at the tables of its seaside casino before the war – had become a killing field for the assaulting troops. Catching quick glimpses of the scene through the swirling smokescreen, he could make out small black, motionless dots on the rocky beach where countless Canadian soldiers now lay dead and wounded, and scores of tanks and landing craft sitting abandoned or burning alongside them. Above the town hung an ominous black, acrid cloud, periodically pierced by German and British fighters swooping down to search out quarry, while rapid-firing anti-aircraft guns from both sides swept the sky with bright yellow and orange tracer fire. The roar of aircraft engines, the sounds of machine-gun and cannon fire, and the explosion of artillery and mortar shells shook the air, as British destroyers attempted to assist the men pinned down on the beach, and now holding on for dear life. 3

Just 700 yards offshore, Fleming watched helplessly as his fledgling commando unit headed through the heavy smokescreen in their landing craft towards the deadly maelstrom. Tragically, what was about to occur was not simply the final act in the darkest day in Canadian military history but the beginning of one of the most controversial episodes of the entire Second World War. This one day in August – August 19, 1942 – would haunt the survivors and leave the country struggling to understand why its young men had been sent to such a slaughter on Dieppe’s beaches.

But what was known only to the young Commander Ian Fleming and a few others was that the raid on this seemingly unimportant French port had at its heart a potentially war-changing mission – one whose extreme secrecy and security ensured that its purpose would remain among the great mysteries of the Second World War. Fleming’s presence on board HMS Fernie connected the deadly Dieppe Raid with the British codebreaking effort (commonly known as ‘Ultra’), one of the most closely guarded secrets of wartime Britain. And understanding exactly why Ian Fleming was on board the Fernie that day was a key that helped me finally to unravel the mystery behind the raid.

Over almost 25 years and through two editions of this book, I combed through nearly 175,000 pages of primary sources and interviewed participants in the raid (as well as filming them for the documentary Dieppe Uncovered, aired simultaneously in England and Canada on August 19, 2012).

Locked away until now in dusty archives, the story unfolded and took shape over time as intelligence agencies and archive facilities in Britain, the United States and Canada released long-classified documents withheld for seven decades from public view. Slowly, each piece was added to the puzzle until, at the end of my journey, I found a story that rivalled a Tom Clancy or a James Bond thriller – although this saga was all too true. And this stunning discovery, kept under wraps until now, necessitates a reconsideration of this phase of the Second World War and a reassessment of the painful legacy of Dieppe.

As Ron Beal, a Dieppe veteran, said to me after I laid out the story for him: ‘Now I can die in peace. Now I know what my friends died for …’ 4

CHAPTER 1

The ‘Canadian’ Albatross

This was too big for a raid and too small for invasion: What were you trying to do?

German interrogator to Major Brian McCool, August 1942

During his intensive interrogation in the days following his capture, the exhausted prisoner, Major Brian McCool, the Principal Military Landing Officer for the Dieppe Raid, was subjected repeatedly to one burning question from his German interrogator: ‘What were you trying to do?’ Still at a loss, the bewildered McCool lifted his head and replied, ‘If you could tell me … I would be very grateful.’

For nearly three-quarters of a century, that same query has remained unanswered despite numerous attempts by historians, journalists and politicians to explain the reasons behind the deadliest amphibious raid in history. The veterans of that fateful day have themselves never understood the abject failure they experienced and the staggering loss of life their comrades suffered on the blood-soaked beaches of Dieppe. Over the decades since, a pitiful legacy of sorrow, bitterness and recrimination has developed to frame the collective Canadian memory of an operation seemingly devoid of tangible purpose and intent.

The cost to Canada of Operation Jubilee, as the Allies’ raid on Dieppe on August 19, 1942, was code-named, was appalling: 907 men 6killed – roughly one man every 35 seconds during the nine-hour ordeal – a rate rivalled only by the charnel-house battles on the western front in the First World War. Adding to that sobering toll, a further 2,460 Canadian names filled the columns of the wounded, prisoners of war and missing in the formal casualty returns. By nightfall, a total of 3,367 men – 68 per cent of all the Canadian young men (mostly in their teens and early twenties) who made the one-day Channel crossing to France – had become official casualties in some form. Units such as the Royal Regiment of Canada from Toronto, which suffered 97 per cent casualties in less than four hours of fighting on Blue Beach at Puys, virtually ‘ceased to exist.’1 To varying degrees, the same was true of the other units of the raiding force: bodies of men from army regiments in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba fell in piles alongside men from the east and west coasts who toiled in the signals, medical, provost, intelligence or service corps.

The catastrophe would strike a deep chord throughout Canada, seared into the country’s psyche as both our greatest historical mystery and our supreme national tragedy. For decades, Dieppe has been Canada’s albatross.

The losses on that day in August 1942 represented a snapshot of Canadian society. The lasting images were stark and unforgiving: the dead – once husbands, fathers, sons, brothers, managers, janitors, students, fishermen, farmworkers and clerks, who had risked their lives in the name of Canada – lay motionless on the pebbled beaches or slumped along the narrow streets of the town, their often mangled bodies used as fodder for German propaganda. Brothers in arms for that campaign, they now rest in the cemetery close by for eternity, bonded and branded by the name ‘Dieppe.’ For those fortunate enough to be taken prisoner, their reward was almost three years of harsh captivity, their hands and feet shackled night and day for the first eighteen months, and a cruel forced death-march in the winter of 1945 over the frozen fields of Poland and Germany. Only after that did the survivors among them reach home.

For many, coming home did not end their Dieppe experience. By then the units they had once viewed as family had rebuilt, and they found few there who had shared their particular experience. Unlike so 7many other veterans, they had no ‘band-of-brothers’ stories to share – of storming the beaches on D-Day, slugging it out in Normandy, liberating French and Belgian towns, or delivering the Dutch from the twin evils of starvation and Nazi Germany – and therefore nothing dislodged the Dieppe stigma. A few of the lucky ones managed to move on, reminded of the ‘shame and the glory’ only at chilly Remembrance Day ceremonies, on muggy August anniversaries or by recurring night terrors. Without proper care for what we now recognize as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), some who could not exorcise the Dieppe demons found temporary solace by lashing out in numerous and at times self-destructive ways instead.

The raid, it should be remembered, was not strictly ‘Canadian’: it was conducted under the overall command of Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Combined Operations Headquarters, and close to 5,000 other Allied soldiers, sailors and airmen, mostly from the United Kingdom, with a smattering of Americans, French, Poles, Belgians and Norwegians, shared the same fateful ordeal in Operation Jubilee. They too were left with lingering frustration about the apparent lack of purpose behind the raid, a vexation captured on the web page of the Juno Beach Centre in Normandy – one of Canada’s military history ambassadors to the world: ‘Dieppe was a pathetic failure,’ it reads, ‘a bizarre operation with no chance of success whatsoever and likely to result in a huge number of casualties.’2

The historical struggle that followed has proven almost as nasty and inconclusive as the battle itself, with the finger-pointing beginning not long after the sounds of conflict faded. Accusations ranged from incompetent leadership to Machiavellian intent after those involved with the planning and conduct of the raid offered up what many felt were deeply unsatisfactory excuses for the disastrous results. The central issue remains, as it has since that raid, the lack of any clear rationale for the intent behind the controversial operation. That absence has left a legacy not only of sorrow but of suspicion, intrigue, mistrust and conspiracy. The common denominator throughout public discourse – that Canadian men had been sacrificed for no apparent or tangible reason 8– led to a sentiment of unease that quickly built up steam in historical accounts, in the press and in public discussion.

Attempting to rationalize what has defied rationalization, researchers and commentators over the decades have sought to make sense out of the seemingly nonsensical. Historians have searched valiantly through the Allied planning papers, after-action reports, personal and official correspondence, and other ancillary documents available in the public domain, looking for any scrap of evidence that would lead to discovering the driving force or imperative behind the Dieppe Raid. Although the planning documents revealed a list of desired objectives for the raid, they remained nothing more than a grocery list of targets that offered little clue to what achieving them would actually mean in the end.

Officially, Prime Minister Winston Churchill would maintain that the raid was merely a ‘reconnaissance in force’ or a ‘butcher and bolt raid’ – explanations that Mountbatten and others associated with the planning and implementation of the raid expanded upon. Before long, another standard excuse emerged: the Dieppe Raid was simply launched to test Hitler’s vaunted Festung Europa (Fortress Europe) and, as such, it was the necessary precursor to future amphibious operations such as the D-Day landings. After that came the ‘sacrificial’ excuses: the Dieppe Raid had been designed by Great Britain specifically to placate its new ally, the beleaguered Soviet Union, by creating the ‘second front now’ that the Russians were demanding, and thereby drawing German air and land forces away from the East and into Western Europe. From there it moved to questions of deception and intrigue and then on to an attritional contest where the raid was conducted to draw the Luftwaffe out into a great blood match with the RAF. These excuses never satisfied the soldiers involved and led to a healthy scepticism among professional and amateur historians alike. Soon, fingers began to point, with suggestions that the leading players in the Dieppe saga all had something to hide.

They were indeed a motley crew, some highly distinguished, others less so, and the reputations of these men have only added to the furore. Lord Louis Mountbatten, the chief of the Combined Operations Headquarters, is traditionally pegged as the main culprit, not so much 9for his headquarters’ handling of the planning and conduct of the raid – as ‘inexperienced enthusiasts’ – but more for his personality and royal bloodlines.3 A vainglorious and ambitious character without a doubt, ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten is traditionally accused of operating far above his ceiling, a man primarily interested in courting the press for favourable headlines designed to put him and his headquarters on the map. But nobody in the chain of command has been spared – all have been painted to varying degrees with the same brush of suspicion, guilt and incompetence. Were the force commanders who called the shots from the distant bridge of the headquarters ship HMS Calpe, offshore from Dieppe, responsible – Canadian Major General John Hamilton ‘Ham’ Roberts and Royal Navy Captain John ‘Jock’ Hughes-Hallett? Or were the highest authorities in wartime Britain, the Chiefs of Staff Committee and, ultimately, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, to blame?

It’s a truth of human nature that any void in our understanding tends to force open a Pandora’s box of wild, seductive and intriguing theories. In this case, they span the spectrum from bureaucratic bungling and inflated ambition to treasonous intent; from impotent claims that the raid was conducted simply for ‘the sake of raiding’ to the intentional tipoff of the Germans as an act of betrayal by the French to gain favour with their occupiers. Or perhaps, some surmise, Dieppe was part of a clever game of foxes – an Allied deception to cover the upcoming invasion of North Africa – or, alternatively, an unauthorized action by Mountbatten to win praise and secure his place in history. Some commentators, citing the relative lack of firepower in the raid, for instance, and the overreliance on the element of surprise, coupled with the unprofessional approach to planning and execution, suggest that the entire operation was sacrificial in nature, intended to fail right from the start, to demonstrate the foolhardiness of American and Soviet calls for a second front in 1942.

Some theories are merely silly and irresponsible, such as the urban legend making the rounds in the cafés along Dieppe’s beachfront today that the raid was an ‘anniversary present’ from Winston Churchill to his beloved wife, Clementine, who in her youth had summered in that delightful Channel port town – a favourite seaside holiday spot for English families. 10

Despite all these efforts to make sense of the Dieppe Raid, however, the mystery has remained intact for over seven decades, taunting us with the pain of its legacy.

That was my own experience long ago in 1995, when I called up a recently declassified file in the British National Archives in London. This wartime British Admiralty file, which at first did not appear to have any connection with the Dieppe Raid, contained an appendix to an ‘Ultra Secret’ classified report concerning the exploits of a highly secret Intelligence Assault Unit (IAU) that, because of its clandestine activities, was known during the war by a variety of names, most notably No. 10 Platoon, X Platoon, 30 Commando or 30 Assault Unit (30 AU). Until the release of that file, there had been nothing to confirm the commando unit’s existence, rumoured to be the brainchild of Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Commander Ian Fleming. Barely a decade later, Fleming would forge another lasting creation – the super-spy James Bond, the most famous, enduring character in espionage literature. The Intelligence Assault Unit was raised and trained with one specific purpose in mind: to steal, or ‘pinch,’ the most sensitive of intelligence materials from the Germans, items needed to break their top-secret codes and ciphers, including the Enigma ciphering machine, allowing the Allies to read enemy message traffic and to wage war effectively.

It was a short passage in the fourth paragraph that started me on my journey of discovery: ‘As regards captures, the party concerned at DIEPPE did not reach their objective.’ The connection was startling: for the first time here was direct evidence that linked one of the greatest and most closely guarded secrets of the entire Second World War – Enigma – with the deadliest day in Canadian military history. Never before had anything similar appeared in the vast corpus of literature dealing with the Dieppe saga. Something that had remained classified as ‘Ultra Secret’ for over half a century by British intelligence appeared to be lurking beneath the veneer of the traditional interpretations of Dieppe.

In June 1941, British intelligence adopted the term ‘Ultra’ as a security classification for intelligence derived from tapping into enemy 11communications, most notably their encrypted radio and later teleprinter traffic. Considered prize intelligence – or, as Winston Churchill called it, his ‘golden eggs’ – ‘Ultra Secret’ went above the traditional top-level classification of Most Secret, or, as the Americans referred to it, Top Secret. Logically enough, the term quickly became a security ‘catch-all’ that not only denoted the end product used by Churchill and his commanders to formulate their decisions on the field of battle, but also extended to the technology, processes, policies, operations and even history centred around the secret British code-breaking facility known as Bletchley Park.

Purchased by the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS, or MI6 as it became popularly known) at the outset of the war, this sprawling Victorian estate in Buckinghamshire, just an hour’s drive north of London, was the main site for the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), which was responsible for signals intelligence (SIGINT) and code-breaking. By military standards, it was a most unusual place: the requirements of the job called for the utmost in intellectual prowess, which meant recruiting some of the most ‘beautiful’ minds that Great Britain, and later the Allies, could offer. The head of operations, Alastair Denniston, had served in British intelligence during the First World War, and now he recruited ‘men of the professor type,’ as he called them, for the new challenge. Drawn mostly from elite universities such as Oxford or Cambridge, these men and women came from a variety of disciplines – mathematics, the sciences, linguistics, classics, history, to name but a few – literally the best and the brightest of the academic world. In this large mansion, they joined forces with gifted intelligence officers (again British and later Allied) from the navy, the air force and the army to produce something that up to that point no other country in history could boast: a relatively consistent and comprehensive ability to tap into a direct information pipeline to monitor their enemy’s strengths, weaknesses, intentions, capabilities, hopes, fears, desires and dreams. As Frank Birch, the head of Bletchley’s Naval Section who had served as a cryptanalyst in the First World War, suggested: ‘There lingered until the end of the war in certain elevated and rarified atmospheres, several of the old popular superstitions about SIGINT (signals intelligence). A familiar one was 12the belief that codes and ciphers were broken by a few freakish individuals with a peculiar kink, no help, and very little material except for the damp towels round their heads.’4

As those in the ‘rarified atmosphere’ would soon learn, Bletchley formed the most potent weapon for a nation at war, and as their importance to the cause increased, so too did the size of Bletchley Park. Soon, numerous numbered ‘huts’ began to spring up around the grounds; these nondescript plywood barracks housed the offices of the naval, air, military and diplomatic sections, which toiled not only to break into, or decrypt, enemy messages intercepted by the many radio intercept stations located around the British Empire, but then to turn what they intercepted and decrypted into sensible and accurate intelligence to be used by the decision-makers to help win the war.

By the end of the Second World War, Sir Harry Hinsley, the official historian of British intelligence, who as a 23-year-old undergraduate in history played an influential role in Bletchley’s Naval Section, concluded that Ultra may not have been the ‘war winner,’ but it was undoubtedly a ‘war shortener.’ By his reckoning, it shaved at least one year, if not two, off the duration of the war, thereby saving millions of lives.5 However, the road was not a smooth one. Although victory ultimately prevailed, mistakes were made along the way.

Information is power, and everyone involved in the Ultra Secret process knew it. In all such cases, then, as now, the enemy must never realize that his supposedly secure communications have been successfully penetrated or, better yet, systematically and consistently penetrated. For this reason, signals intelligence and code-breaking, or cryptography, must be conducted in the strictest secrecy, or the enemy will catch on and change the codes and ciphers that guard his message traffic.

Because of its vital military importance and potential, Ultra became one of the most cherished and carefully guarded secrets of the war, surpassing even the development of the atomic bomb in the post-war era. Ultra required elaborate precautions to maintain its security, given that more than 10,000 people played various roles connected with it by war’s end. Such was the secrecy surrounding the work in Bletchley Park that all those who worked and lived there – from the clerks and young 13female secretaries to the brilliant code-breaking ‘boffins’ – knew that to talk about their work informally, even to dorm mates or colleagues outside their hut, was treasonous and could result in lifetime imprisonment or even execution. Accordingly, the security surrounding Ultra was to be maintained indefinitely.

As things turned out, the very existence of Ultra remained under wraps for over 30 years following the conclusion of the war. In the late 1970s, for reasons that are still unclear today, the British government officially, and some say unwisely, acknowledged Ultra. Even then, it took close to two more decades before the first batches of significant documents were released to the public – a release that began in 1995, on the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War, and continues in a piecemeal fashion to this day.

Such was the nature of the recently declassified document I had unearthed in the British National Archives. As I continued to scan the pages of the document, the experience reminded me of a miner discovering his first nugget, wondering if he has indeed tapped into a lucrative vein or simply into ‘fool’s gold.’ Thus began my nearly two-decade historical journey in search of the truth behind Dieppe.

The information contained in the document only increased my natural curiosity. What was the ‘objective’ of this ‘party’? What role did the objective play in the overall context of the raid? Could it have been a long-concealed reason for the Dieppe Raid? The document offered nothing more direct than that one sentence – ‘the party concerned at DIEPPE did not reach their objective’ – but it struck me immediately as a potential game changer. Included in the document was a general ‘target list’ of items that Commander Ian Fleming’s Intelligence Assault Unit had been asked to pinch in the summer and autumn of 1942. Labelled ‘Most Urgent,’ the items on the list all related to the four-rotor Enigma cipher machine that the German navy (Kriegsmarine) had recently introduced to encrypt its messages before they were sent via wireless. Among these items were ‘specimens of the wheels used on the Enigma machine, particulars of their daily settings for wheels and plugs, codebooks, and all documents relating to signals and communications,’ as well as anything connected with the German signals intelligence effort against British communications. Given my 14background as a signals intelligence and Ultra historical specialist for the Department of National Defence in Canada, those lists made perfect sense in the context of the times.

Mid-1942 was the desperate ‘blackout’ period for the British Naval Intelligence Division (NID). Thanks to the cryptanalysts working around the clock in Bletchley Park, for nearly a year – from the spring of 1941 to February 1942 – the British had enjoyed astonishing success in intercepting and decrypting German navy messages between its headquarters and its surface and U-boat fleets. During that period, German communications were encrypted on a three-wheel Enigma machine – a complex electromechanical rotor cipher machine belonging to a family of devices (the army, navy and air force each had their own version) first developed by the Germans at the end of the First World War. To do their work, the cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park relied on pinched material – Enigma machines captured from destroyed submarines, for instance, or, more importantly, the codebooks, rotor-setting sheets and instruction manuals used to unravel the German secret transmissions. So great was their success, both in stealing materials from the Germans and in intercepting and decrypting the German messages, that the Naval Section at Bletchley Park euphorically nicknamed 1941 the annus mirabilis, the ‘year of miracles.’6

But the miracle ended abruptly on February 1, 1942, when the German navy ordered its U-boat arm operating in the Atlantic to encipher their top-secret messages on an improved and more complex four-rotor version of the Enigma machine that left the expert codebreakers at Bletchley hopelessly in the dark. The next ten months were a frantic and dangerous time for Great Britain – in particular for her Admiralty and Naval Intelligence Division. Due to a combination of factors, all exacerbated by the Bletchley code-breakers’ sudden inability to read the German messages and locate enemy submarines before they attacked, merchant shipping losses in the Atlantic suddenly skyrocketed, seriously threatening Britain’s vital oceanic supply and trade routes.

There was near panic in some circles over the perceived threat to the Allies’ command of the vital sea lanes essential to ultimate victory in the war. Fortunately for the Allies, when the Germans introduced 15their updated four-rotor Enigma, they possessed only enough of these machines to equip their Atlantic fleet, leaving for the moment all the other areas of operation – the Mediterranean Sea, the Baltic, Norway and the German home waters – with the three-rotor machine and still vulnerable to Bletchley’s code-breaking skills. But the Royal Navy’s Intelligence Division knew the clock was ticking as they discovered early in 1942 that now surface vessels operating in the English Channel and in Norway had been outfitted with new four-rotor machines but had yet to put them into operation. Obviously, it was only a matter of time before they became operational and extended the blackout from the potent U-Boat arm to the entire Kriegsmarine. This growing crisis led directly to the creation of Ian Fleming’s commando unit, operating under the aegis of the Naval Intelligence Division and focused solely on ‘the pinch.’

As I read on, the document outlined the criteria for the commandos in Fleming’s new Intelligence Assault Unit: they should be familiar with the materials targeted in a pinch but not indoctrinated into the mysterious world of Ultra and Bletchley Park in case, God forbid, they fell into enemy hands and cracked under interrogation. In addition, the unit would include a special adviser with experience in ‘commando raids’ and ‘cutting-out parties’ to guide in the selection of targets and later compile a list of lessons learned. Here, one cautionary note in the report stood out supreme for me: ‘No raid should be laid on for SIGINT purposes only. The scope of the objectives should always be sufficiently wide to presuppose normal operational objects.’7

That passage, in light of the Ultra Secret designation, raised some startling new questions: If Commander Ian Fleming’s specially raised and trained commando unit was targeting Dieppe, was this pinch the purpose and intent behind Operation Jubilee, the raison d’être for the raid? Could the initial motive for the raid on Dieppe be, as that last passage suggested, to provide a cover under which the commandos could raid a specific target in Dieppe and then depart without rousing German suspicions? Could it even be that the pinch of the target materials, under cover of the other objectives, was the driving force for the entire operation – a scenario that seems ripped from the pages of an Ian Fleming or Tom Clancy spy thriller? 16

Fleming’s inclusion in the raid to oversee his nondescript commando unit, which was making its combat debut, had earlier raised no questions. Traditionally, it has always been viewed as a lark or a ‘day trip’ to Dieppe. But knowing now what his commando unit was targeting opened up an unexpected avenue for a fundamental reassessment of the Dieppe Raid. The potential implications were staggering.

Fully aware of the importance of Dieppe in the Canadian psyche, I realized that my theory required substantial investigation before it could even be proposed – something that proved daunting and near impossible in 1995 for the simple reason that few classified British intelligence files had been released into the public domain. It was true that millions of pages had become available to historians and researchers on the fiftieth anniversary of the war’s end, but the British, American and Canadian governments still held back critical intelligence files that they regarded as too sensitive or potentially too controversial to release at that time. So, over the next two decades, as more documents slowly became available, my investigation continued and resulted in the first edition of this book in Canada, which then accelerated more releases of classified material that prompted the writing of this edition.

In 2010, with the vast majority of the research and most of the central pieces in place, it was time to take my journey to another level. I set out my argument to the historians at the Royal Navy’s Historical Branch in Portsmouth and the Government Communications Headquarters in Cheltenham. My thesis came as a shock to both groups but they both separately offered that I was indeed ‘on to something,’ because they too were curious about the Dieppe mystery. The chief historian at the Government Communications Headquarters agreed to a further public release of classified files dealing with the contextual story of pinch operations, including reports of previous similar operations and vital documents on pinch policy or ‘doctrine.’ These documents provided a series of small but highly significant ‘eureka moments’ that helped me to round out the Dieppe saga. Many times I felt I was building a complex historical jigsaw puzzle that had begun with just one tantalizing piece and grew year by year until I felt comfortable enough to come forward with the findings. 17

This work has indeed kicked at the darkness until it has bled daylight. Now, after close to eight decades, we can lift the albatross from our shoulders and move past the initial sorrow, anger, excuses, recrimination, and bitterness to achieve something essential – a genuine understanding of the reasons for the raid on Dieppe. In this way, we can honour those who sacrificed so much on that one day in August 1942. 18

CHAPTER 2

A Very Special Bond

My job got me right into the inside of everything, including all the most secret affairs. I couldn’t possibly have had a more exciting or interesting War.

Ian Fleming, the Playboy interviews

Many of us love to revel in all things James Bond, so the legend of Ian Fleming’s charismatic and unsinkable 007 has fused over the decades with the legend of his creator. Was he a spy himself? Was he a crack commando? Did he or did he not train to become a secret agent in Camp X, outside Whitby, Ontario, under the famous William Stephenson, the ‘man called Intrepid’? Speculation and fantasy, all. As Ernest Cuneo, the American Intelligence Liaison officer who worked with Fleming during the war and later collaborated on the early Bond films recalled, ‘James Bond is no part of Ian Fleming … it reflects merely his cynicism.’1

Until recently, for the serious historian, it seemed almost inconceivable that Bond’s creator played more than an ephemeral role in planning the tragic raid that August day at Dieppe – and so it appeared to me too, initially. Yet the information I began to unearth as I went deeper into this story reveals a very different Ian Fleming circa 1942. 20

It all began three years earlier, in the late spring of 1939, when Rear Admiral John Godfrey, the 51-year-old, silver-haired though balding new director of the Naval Intelligence Division, invited Fleming, twenty years his junior, for lunch at the fashionable Carlton Grill – the restaurant in one of London’s most luxurious hotels off Whitehall, once ruled over by the French master chef Auguste Escoffier.*

At that luncheon on May 24, Godfrey was just three months into his appointment, and he wanted to meet Fleming, a former journalist turned stockbroker, with the idea of appointing him as his personal assistant. Godfrey’s mentor, Admiral Sir William ‘Blinker’ Hall, the legendary spymaster from the First World War, had suggested he should hire someone to help him with his overwhelming pressures and responsibilities in a world verging on war, particularly in the now long-neglected Intelligence Division.2

John Godfrey immediately reached out for suggestions for a worthwhile candidate.3 As with most things in the shadowy world of British intelligence and espionage in those days, Fleming’s name reached him through the time-honoured old boys’ network – specifically Sir Montagu Norman, the longest-serving governor of the Bank of England.4 Fleming, like Norman, had been tempered at Eton, the prestigious boys’ school that had crafted the character of generations of the privileged class, preordained for positions of power within the British Empire. The brief resumé Godfrey received seemed impressive enough: the young journalist had achieved a modicum of notoriety dabbling as an ‘occasional informant’ for the Secret Intelligence Service while covering the Russian beat for Reuters in the 1930s.5 And he was made of the right stuff: he was the grandson of Robert Fleming, the founder of Robert Fleming & Company in Dundee, which produced jute-based products during the American Civil War years before moving on to investments in the lucrative American railroad industry. Eventually, he had transformed ‘the Flemings’ into one of the last private merchant 21banks that focused on mergers and acquisitions, putting it on the financial map on both sides of the Atlantic alongside J.P. Morgan, Jacob Schiff, and Kuhn, Loeb & Co.6

Robert’s two sons, Valentine (Val) and Philip, followed in the family business until 1910, when Val, Ian’s father, won a seat in Parliament. A product of Eton and Oxford, Val became a rising star in the Conservative Party, ‘a pillar of the landed squirearchy.’7 On the outbreak of war in 1914, he and Philip joined the dashing Queen’s Own Oxfordshire Hussars.8 After fighting through the second battle of Ypres the following spring, Val was twice mentioned in dispatches and earned the Distinguished Service Order before succumbing to German artillery shells in the autumn of 1917, just one week before Ian’s ninth birthday. Val’s friend and parliamentary ally, the brash, outspoken Winston Churchill, penned his obituary for the Times.9 Little did anyone know then that the former First Lord of the Admiralty, at that point disgraced for having staunchly backed the Gallipoli debacle one year into the war, would reappear two decades later out of the political wilderness. Less than a year after Fleming’s introductory luncheon with Godfrey, Churchill reclaimed the political reins of power at the Admiralty and moved on to even greater heights as minister of defence, and in May 1940 he added the portfolio of prime minister at the darkest moment in British history.

Graced with a ‘fine head, a high forehead with a head of thick brown, curlyish hair, parted on the side and neatly combed over to the left,’ Fleming exuded sophisticated confidence despite ‘a somewhat aloof manner.’10 His shoulders were ‘average large, his waist thickish.’ He possessed a ‘good, firm jaw’ with ‘piercing blue eyes’ separated by a nose that had been ‘broken and unrepaired.’11 His sad, bony face with its clear blue eyes was strong-featured, despite the disjointed nose he had acquired during his athletic days at Eton, which only added to ‘his rakish allure.’12 Tall and slim, Fleming moved gracefully and with purpose but carried himself ‘more like an American than an Englishman’ for he did not rest his weight on his left leg but rather distrusted it, with his left foot and shoulders slightly forward, giving him the look of a ‘Philadelphia light-heavyweight’ that contained ‘more of a hint of the boxer’s crush than the squared erect shoulders of a Sandhurst man.’1322

Like many other trust-fund babies who came of age in the wake of his father’s ‘lost generation,’ he lived a carefree life. He had left the Royal Military College at Sandhurst after allegedly contracting a venereal disease; the rumour cast a cloud over his character and general suitability for a King’s commission. His distraught mother, fearing for his psychological well-being, sent him to a kind of finishing school for men in Kitzbühel, Austria, where, along with skiing and mountain climbing, he came under the influence of Ernan Forbes Dennis, a former British spy, and his wife, Phyllis Bottome, a novelist. They encouraged Fleming’s aptitude for languages and suggested he start writing. Considering a career in diplomacy, he next enrolled in universities in Munich and Geneva but soon developed a reputation as a playboy. He travelled through Europe at his family’s expense, trying sporadically to write between visits to taverns, casinos and brothels, chain-smoking and already drinking too much. When he failed the competitive examination for the Foreign Office, his mother managed to secure him a position as a journalist with Reuters News Agency, where he reported from Moscow on the trial of some British engineers accused of spying. Given his charm, Fleming also made friends in influential circles. When he returned to England, he joined a prestigious brokerage firm.

Fleming’s ability to operate in French, German and Russian impressed Godfrey, as did his ‘talent for spare and simple prose,’ developed while writing for Reuters.14 But there was much more to Fleming than his social, linguistic and writing skills. Like many people who leave an indelible impression on their peers, he was a wealth of contradictions. ‘At the first encounter,’ recalled his friend William Plomer, who later became his editor at Jonathan Cape for most of the Bond books, ‘he struck me as no mere conventional young English man-of the-world of his generation; he showed more character, a much quicker brain, and a promise of something dashing or daring. Like a mettlesome young horse, he seemed to show the whites of his eyes and to smell some battle from afar.’15 Indeed, as Cuneo lamented, ‘Fleming was as spirited as a warhorse before battle.’16

In large part, what attracted Godfrey to Fleming was the young man’s intense interest in cryptography – an intelligence source that Godfrey knew all too well had been vital to the outstanding success 23of Naval Intelligence during the First World War. Fleming had always been a student of the philosophical underpinnings of science and technology and their impact on society, a passion that led him to amass an impressive collection of first-edition works that in one way or another transformed the world.17 Half in jest, Fleming would later argue that the moniker ‘C,’ used to denote the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service, did not refer to Sir Mansfield Cumming (its first head) as everyone thought, but to Charles Babbage, widely referred to as the ‘father of the computer.’18

In 1822, nearly a century and a quarter before Bletchley Park unleashed the world’s first computer, Babbage, assisted by parliamentary funding, embarked on the development of his ‘Second Difference Engine.’19 Unfortunately, official patience soon ran dry, leaving the development of ‘the computer’ on the sidelines until the Second World War, when Britain’s very survival demanded assistance beyond human intelligence. The fact that Babbage’s invention could have rivalled or even eclipsed Gutenberg’s printing press as the most influential technological development in a millennium, affording Great Britain an unmatched industrial advantage, was not lost on Fleming. Babbage and his cryptographic passion became Fleming’s own fervent intellectual pursuit: he studied his writings carefully, captivated by passages on the art and science of deciphering, which Babbage had compared to picking locks.20 Various segments from Babbage’s seminal Passages from the Life of a Philosopher, published in 1864, were, according to Fleming, the ‘most cherished’ in his collection.21

Apart from his intellectual interests, there was a darker side to Fleming that Godfrey came to appreciate and even foster. Although some viewed him as ‘the warmest kind of friend, a man of ready laughter and a great companion,’ others remarked that Fleming was ‘a totally ruthless young man [who] didn’t consider anyone’ – a sentiment shared by Godfrey, who said that Fleming ‘had little appreciation of the effects of his words and deeds upon others.’22 Cuneo, to a degree, concurred: ‘Moody, harsh, habitually rude and often cruel’ described ‘some of his actions’ but ‘does not describe the man.’23 Cuneo, instead, found him ‘quite simple to understand’ within the complex class structure of the time. ‘He was not English, he was a Scot by his father’s line, only third 24generation in a class structure which reserves its highest accolades for the peerage, and even within … grades the standings on the length and quality of title. Ian Fleming was not a peer of the realm.’

Cuneo believed that Fleming ‘felt no particular discontent with himself. He felt much discontent with the world in which he lived, for he was a knight out of phase, a knight errant searching for the lost Round Table and possibly the Holy Grail, and unable to reconcile himself that Camelot was gone and still less that it had probably never existed.’24

He was best at dealing with things and ideas rather than people. ‘He was primarily a man of action,’ Godfrey wrote, whose ‘great ability did not extend to human relations or understanding of the humanities.’25 Fleming’s Machiavellian flair flourished in the Naval Intelligence Division, where an ‘element of ruthlessness and perfidy, verging on the unscrupulous, [was] inherent in certain intelligence activities.’26 As Cuneo, who performed similar functions for the United States Office of Strategic Services, recalled: ‘Ian Fleming knew exactly what he was trying to do’ with ‘not the slightest presumption of innocence.’ Although ‘Fleming never killed a man with his own hand,’ Cuneo recalled, ‘during the war, like everybody else, we [were] engaged in helping to kill thousands.’27

Fleming was a civilian, quite unlike ‘service-trained officers imbued with the instinct to “play the game” … a maverick who had a gambler’s instinct and a taste for adventure.’28 From Godfrey’s perspective, Fleming possessed intellectual flexibility that let him easily transform, engage with and understand any problem, idea or concept with equal ease, whether in a formal work setting or over drinks and a meal. In many ways, Fleming reminded Godfrey of Churchill: he ‘had plenty of ideas and was anxious to carry them out, but was not interested in, and preferred to ignore the extent of the logistic background inseparable to all projects.’29 To Plomer, Fleming ‘always seemed to take the shortest distance between two points in the shortest possible time’; to which Cuneo concurred, for ‘Ian habitually, almost compulsively, sought in games of chance, the chance in a million.’30

25And so it happened that, in May 1939, Admiral Godfrey offered Fleming the job of personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI). He had no obvious training or experience for the role, but neither did most of the men (and fewer women) recruited into the secret services at that time. Rather, his primary traits were initiative, imagination, brains, and a tireless commitment to winning the war, not so much on the battlefield as in the world of intelligence.